Key Clinical Message

Frostbite arising from nitrous oxide (N2O) inhalation is rare. As such, there is no consensus on best treatment for these injuries. In all published reports, judicious use of corticosteroids and antibiotics has resulted in positive clinical outcomes; we endorse these agents in our case of a young man with oropharyngeal burns.

Keywords: inhalant injury, nitrous oxide, oropharyngeal frostbite, volatile substance abuse

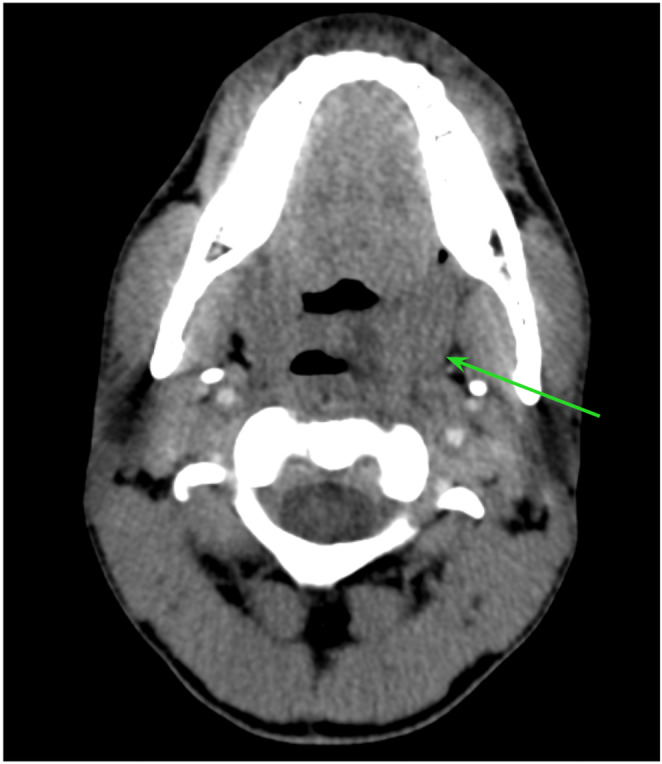

Left oropharyngeal burn resulting from nitrous oxide inhalation.

1. INTRODUCTION

The euphoric properties of inhaled nitrous oxide (N2O) lend to its frequent recreational use. N2O was the first drug used as a surgical anesthetic, and through modulation of opioid receptor and spinal nociceptive processing, and γ‐aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor activation, has additional analgesic and anxiolytic effects. 1 Onset of action is quick, within seconds, and generally lasts only minutes. 2 In Australia, an annual survey of regular illicit drug users found concurrent use of N2O had risen to 53% of those sampled in 2019, from 23% 5 years earlier. 3 N2O now ranks as the second most popular recreational drug in Britain. 2 While commonly perceived to be safe, N2O inhalation at high concentrations causes hypoxia and possible asphyxiation, and prolonged use has been shown to induce functional vitamin B12 deficiency. 1 , 2 The latter may progress to cause peripheral neuropathy and megaloblastic anemia. 2

Given its boiling point of −128 °F (−89°C) at atmospheric pressures, 4 the gas must be stored carefully in pressurized steel cylinders. Where there is accidental or intentional contact with the pressure‐reducing valves of these cylinders, frostbite injuries can occur. Oropharyngeal frostbite secondary to volatile inhalant abuse has been described only in a small number of case reports; far fewer have been attributed to N2O exposure specifically. Below, we describe a case of upper aerodigestive tract injury following intentional recreational use of N2O.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient; single case reports are exempt from institutional review board evaluation at our service.

2. CASE REPORT

A 30‐year‐old male was referred by his general practitioner to a small metropolitan hospital with a worsening sore throat, odynophagia, subjective dysphonia, and sensation of throat swelling 2 days following inhalation of N2O from a whipped cream canister at a party. The patient reported his symptoms to be of immediate onset at the time of inhalation, but delayed seeking medical attention until the next day in the context of concurrent amphetamine use. On initial review, the patient did not show any increased work of breathing, and maintained oxygen saturations of 98% without any supplemental requirement. He had a hoarse voice, with desquamation of the left tonsil and adjacent soft palate, and associated anterior neck tenderness. There was no trismus or subcutaneous emphysema. He was able to tolerate liquids but unable to swallow any solids, and experienced moderate pain. He had no systemic symptoms and had not suffered burns to any other region of his body. The patient had no significant past medical history, nor any regular medications.

Initial management consisted of single‐dose 8 mg intravenous dexamethasone, and intravenous 1.2 g amoxicillin‐clavulanic acid Q8H. Cross‐sectional computed tomography (CT) imaging with contrast demonstrated left‐sided oropharyngeal mucosal swelling and oedema, and slight narrowing of the oropharyngeal airway (Figure 1). There was no subcutaneous gas. The patient was then transferred to a tertiary hospital for specialist otolaryngology review. Flexible nasendoscopy performed 72 hours post‐injury showed only desquamation of the left tonsil and adjacent soft palate. By this stage, the patient's symptoms had largely resolved, and he was not requiring any form of analgesia; clinical appearances were stable (Figure 2). The next morning, 86 hours post‐injury, his dysphonia had resolved and he was comfortably tolerating oral intake. He was accordingly discharged with a course of oral amoxicillin‐clavulanic acid (875–125 mg BD for 5 days).

FIGURE 1.

Computed tomography appearance of left oropharyngeal burn (Green arrow).

FIGURE 2.

Clinical appearance of left oropharyngeal burn (90 h post‐injury).

3. DISCUSSION

The sequelae of N2O misuse are well‐documented and include frostbite, polyneuropathy, and hypoxia; the latter in particular has proven fatal. 2 Oropharyngeal frostbite, however, is rarely described. On a review of the literature, we were able to identify six cases of upper aerodigestive tract frostbite secondary to volatile inhalant use, of which two were N2O‐related.

The treatment and outcome of N2O‐induced oral frostbite are not well‐established, given its rarity. In 1996, Svartling et al reported a case of third‐degree frostbite to the mouth, oral cavity, and upper airways. 5 The patient required tracheostomy for airway safety and underwent a protracted course of debridement of necrotic tongue, hard palate, and buccal tissue. 5 While the patient was able to be discharged after 18 days, they required ongoing review over months for oral cavity scarring with associated trismus. 5 Although the extent of injury is significantly different from our case, several treatment modalities were utilized by the treating teams in both instances. Following commencement on ventilatory support, Svartling's patient also received intravenous steroids and antibiotics (methylprednisolone, cefuroxime and metronidazole), although dose and duration of therapy was unspecified. 5

Chan et al described a case of aerodigestive tract injury following N2O inhalation from an automotive canister; this was mixed with sulfur dioxide to deter recreational inhalation, which carries its own corrosive properties. 6 In this instance, the patient presented with voice change, edema and erythema affecting the lips, buccal mucosa, palate, and oropharynx. 6 Due to a six‐liter supplementary oxygen requirement to maintain saturations >85%, with associated edema of the nasopharynx and supraglottis, a decision was made to intubate via an awake fiberoptic method. 6 As with our case, this patient received intravenous dexamethasone, of unspecified dose and duration. 6 It is unclear whether the patient received antibiotics at any stage, but topical sucralfate was applied to his oral cavity burns to good effect. 6 The peak of airway edema appears to have passed quickly; the patient's airway remained stable following self‐extubation 24 hours post‐injury. 6 Subsequent follow‐up was encouraging, but was only reported to 2 weeks. 6

Although the causative agent in all these cases is N2O, ours is the first case involving a whipped cream dispenser as the method of delivery into the oral cavity. This is significant, as pressures within whipped cream canisters are much lower (30 psi) 7 relative to storage canisters for medical use in anesthesia (as in the first case) 5 and automotive canisters (causative in the second); the pressures in the latter device are estimated at 950 psi. 6 While degree of injury across these cases approximately correlates with force of pressure delivered, our case increases the index of suspicion for significant oropharyngeal frostbite injury even at low pressures of barotrauma.

4. CONCLUSION

Otolaryngologic sequelae of inhaled N2O use are rare. However, we have identified a case of frostbite to the soft palate as an example requiring acute otolaryngologic assessment and management. We have shown that even the relatively low pressures applied through N2O inhalation can result in clinically significant frostbite, although degree of barotrauma seems to influence degree of subsequent edema. Given the paucity of published literature, there is no consensus on management of such injuries, but with their known effects in amelioration of airway edema, administration of intravenous steroids is considered fundamental to management.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Antonia C Rowson: Data curation; writing – original draft. Matthew X Yii: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing. Hannah B Tan: Writing – review and editing. Jessica Prasad: Supervision; writing – review and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors report no commercial or proprietary interest in any product or concept discussed in this article.

CONSENT STATEMENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the subject of this report.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None. Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Sydney, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Sydney agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Rowson AC, Yii MX, Tan HB, Prasad J. Recreational nitrous oxide‐induced injury to the soft palate. Clin Case Rep. 2023;11:e7858. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.7858

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Emmanouil DE, Quock RM. Advances in understanding the actions of nitrous oxide. Anesth Prog. 2007;54(1):9‐18. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006(2007)54[9:AIUTAO]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van Amsterdam J, Nabben T, van den Brink W. Recreational nitrous oxide use: prevalence and risks. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2015;73(3):790‐796. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2015.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peacock A, Karlsson A, Uporova J, et al. Australian Drug Trends 2019: Key Findings from the National Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System (EDRS) Interviews. National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre; 2019:70. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barker SJ, Tremper KK. Physics applied to anesthesia. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, eds. Clinical Anesthesia. 1st ed. JB Lippincott Co; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Svartling N, Ranta S, Vuola J, Takkunen O. Life‐threatening airway obstruction from nitrous oxide induced frostbite of the oral cavity. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1996;24(6):717‐720. doi: 10.1177/0310057X9602400617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chan SA, Alfonso KP, Comer BT. Upper aerodigestive tract frostbite from inhalation of automotive nitrous oxide. ENT‐Ear, Nose Throat. 2018;97(9):E13‐E14. doi: 10.1177/014556131809700903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sellers WF. Misuse of anaesthetic gases. Anaesthesia. 2016;71(10):1140‐1143. doi: 10.1111/anae.13551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.