Abstract

Introduction

MET amplification is a known resistance mechanism to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment in EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Dual EGFR-MET inhibition has been reported with success in overcoming such resistance and inducing clinical benefit. Resistance mechanisms to dual EGFR-MET inhibition require further investigation and characterization.

Methods

Patients with NSCLC with both MET amplification and EGFR mutation who have received crizotinib, capmatinib, savolitinib, or tepotinib plus osimertinib (OSI) after progression on OSI at MD Anderson Cancer Center were included in this study. Molecular profiling was completed by means of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and next-generation sequencing (NGS). Radiological response was assessed on the basis of Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1.

Results

From March 2016 to March 2022, 23 treatments with dual MET inhibitor and osi were identified with a total of 20 patients included. Three patients received capmatinib plus OSI after progression on crizotinib plus OSI. Median age was 64 (38–89) years old and 75% were female. MET amplification was detected by FISH in 14 patients in the tissue, NGS in 10 patients, and circulating tumor DNA in three patients. Median MET gene copy number was 13.6 (6.4–20). Overall response rate was 34.8% (eight of 23). In assessable patients, tumor shrinkage was observed in 82.4% (14 of 17). Median time on treatment was 27 months. Two of three patients responded to capmatinib plus OSI after progression on crizotinib plus OSI. Dual EGFR-MET inhibition was overall well tolerated. Two patients on crizotinib plus OSI and one pt on capmatinib plus OSI discontinued therapy due to pneumonitis. One pt discontinued crizotinib plus OSI due to gastrointestinal toxicity. Six patients were still on double TKI treatment. At disease progression to dual EGFR-MET inhibition, FISH and NGS on tumor and plasma were completed in six patients. Notable resistance mechanisms observed include acquired MET D1246H (n = 1), acquired EGFR C797S (n = 2), FGFR2 fusion (n = 1, concurrent with C797S), and EGFR G796S (n = 1, concurrent with C797S). Four patients lost MET amplification.

Conclusions

Dual EGFR and MET inhibition yielded high clinical response rate after progression on OSI. Resistance mechanisms to EGFR-MET double TKI inhibition include MET secondary mutation, EGFR secondary mutation, or loss of MET amplification.

Keywords: Resistance mechanisms, MET, EGFR, NSCLC

Introduction

EGFR mutations occur in 40% to 60% of the Asian population and in 10% to 15% of the western population in NSCLC.1 Osimertinib, a third-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), is the most used frontline treatment for metastatic EGFR-mutant NSCLC.2 MET amplification (METamp) accounts for 7% to 15% of resistance mechanisms after progression on osimertinib, which can be detected by means of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or next-generation sequencing (NGS).3 Dual EGFR-MET inhibition with osimertinib plus savolitinib (TATTON, ORCHARD, and SAVANNAH trials) or osimertinib plus tepotinib (INSIGHT 2 trial) has reported successes in overcoming such METamp-mediated resistance and produces clinical benefit in phase 1 to 2 clinical trials.4, 5, 6, 7 It is anticipated that use of dual EGFR-MET inhibition will become increasingly common in clinical practice; therefore, resistance mechanisms to dual EGFR-MET inhibition require further characterization. In this study, we report a single-center, retrospective analysis on clinical benefit, toxicities, and acquired resistance mechanisms to dual EGFR-MET inhibition in patients with EGFR-mutant, MET-amplified NSCLC who progressed on osimertinib and MET inhibitors.

Materials and Methods

Patient Population

We reviewed the GEMINI-Moonshot, clinical and pharmacy database of patients with metastatic NSCLC treated at MD Anderson Cancer Center, from March 2016 to April 2022 to identify patients who have received concurrent crizotinib, capmatinib, savolitinib, or tepotinib plus osimertinib after progression on osimertinib. Patients were not required to receive dual MET-EGFR inhibition sequentially after progressing on osimertinib; other systemic therapies were allowed. After progression on crizotinib plus osimertinib, a different MET inhibitor combined with osimertinib was allowed. Radiological response was performed approximately every 2 to 3 months according to standard of care. This study was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Data collection was performed under MD Anderson Cancer Center institutional review board–approved protocol PA13-0589 with informed consent. All available clinical information was collected from electronic medical records (EMRs).

Clinical Response and Toxicity Evaluation

Radiological response was on the basis of the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 assessed by a radiologist. Safety and adverse events (AEs) were identified through EMR and retrospectively assessed on the basis of Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5. Clinical benefit was defined as treating physician’s judgment of symptom improvement and shrinkage of cancer per imaging studies.

Molecular Detection Methods

Molecular results were obtained through EMR as part of standard of care. NGS was used to evaluate EGFR alterations in tissue and plasma or circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) from plasma. MET was evaluated with either FISH on tissue or NGS on tissue and plasma. METamp was defined as a gene copy number (GCN) more than or equal to 5 on FISH or an amplification detected on NGS on tissue and plasma (Supplementary Table 1).

Results

Patients, METamp Detection, and Treatments

At the data cutoff on April 29, 2022, 20 patients received dual MET inhibitor and osimertinib. Median age at diagnosis was 64 (range: 38–89) years old and 75% were female. Three patients received capmatinib plus osimertinib after progression on crizotinib plus osimertinib; therefore, there were 23 treatments identified. The median number of previous lines of therapies was two. Nine patients had brain metastases before starting double TKIs, including seven patients who had radiotherapy treatment of brain metastases and two patients with untreated brain metastases. METamp was detected by means of FISH in 14 patients, and median MET GCN was 13.6 (range: 6.4–20) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2). Fifteen patients were confirmed to develop METamp after progression on osimertinib. In addition, 12 of the 20 patients received platinum doublet-based chemotherapy after progression on osimertinib. The most often used regimen was carboplatin, paclitaxel, bevacizumab, and atezolizumab followed by carboplatin and pemetrexed with or without bevacizumab. Objective response rate (ORR) was 41.7% (n = 5), and disease control rate was 58.3% (n = 7). Median duration of treatment with chemotherapy-based regimen was 4.6 months (0.8–40.5) (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 1.

Patient and Tumor Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristics | Overall Population (N = 20) |

|---|---|

| Median age | 64 |

| Female, n (%) | 15 (75) |

| Histology, n (%) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 18 (90) |

| NSCLC (NOS) | 2 (10) |

| EGFR mutation at baseline, n (%) | |

| EGFR L858R | 11 (55) |

| EGFR exon19del | 9 (45) |

| MET amplification detection method (n) | |

| FISH | 14 |

| NGS on tissue | 10 |

| ctDNA | 3 |

| Average MET GCN | 13.6 |

| Onset of MET amp, n (%) | |

| After progression on frontline osimertinib | 9 (45) |

| After progression on two previous lines of therapy | 3 (15) |

| After progression on three previous lines of therapy | 2 (10) |

| After progression on four previous lines of therapy | 1 (5) |

| Median previous lines of therapy | 2 |

| Patients received previous platinum-based chemotherapy (n) | |

| Chemotherapy with immunotherapy | 6 |

| Chemotherapy | 6 |

| Baseline brain metastases before double TKIs (n) | |

| Present, treated | 7 |

| Present, untreated | 2 |

| Combination used (m) | |

| Crizotinib plus osimertinib | 12 |

| Capmatinib plus osimertinib | 6 (3 after crizotinib + osimertinib) |

| Savolitinib plus osimertinib | 3 |

| Tepotinib plus osimertinib | 2 |

ctDNA, circulating tumor DNA; exon19del, exon 19 deletion; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; GCN, gene copy number; MET amp, MET amplification; NGS, next-generation sequencing; NOS, not otherwise specified; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Clinical Response and Toxicities of Double TKIs

Among the 23 treatments with a MET inhibitor and osimertinib, 17 had assessable radiological response, five were nonassessable due to lack of target lesion, and one was nonassessable due to lack of follow-up. ORR was 34.8% (eight of 23) in the total population. In the assessable population, ORR was 47.1% (eight of 17) (Fig. 1A). Tumor shrinkage was observed in 82.4% (14 of 17) of the assessable population. Disease control rate was 88.2% (15 of 17) in the assessable population. Clinical benefit determined by physicians was 65% (15 of 23). Median time on treatment was 27 (range: 1.3–37.0) months (Fig. 1B and C). Two of three patients had clinical response to capmatinib plus osimertinib after progression on crizotinib plus osimertinib. One of two patients with untreated brain metastases had intracranial response. No CNS progression was observed for the entire cohort. Six patients were still on dual EGFR-MET inhibition (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Clinical response to osimertinib plus MET inhibitors. (A) Tumor size change in patients with measurable disease. n = 17. (B) Time of response, time on treatment, and duration of previous EGFR TKI. n = 20. (C). Time on treatment. Kaplan–Meier curve. n = 23. cap, capmatinib; criz, crizotinib; NE, not evaluable; osi, osimertinib; PD, progression on disease; PR, partial response; sav, savolitinib; SD, stable disease; tepo, tepotinib; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

The most often documented AEs include increased serum creatinine (n = 9, 39%), nausea (n = 8, 35%), diarrhea (n = 8, 35%), and fatigue (n = 5, 21%). Arthralgia, myalgia, paronychia, rash, and edema were less frequently observed. Grades 1 to 2 increased serum creatinine level was the most frequent AE in patients who received capmatinib plus osimertinib (n = 4) and crizotinib plus osimertinib (n = 4). Grade 3 anemia was observed in one patient on crizotinib plus osimertinib. Two patients on crizotinib plus osimertinib and one patient on capmatinib plus osimertinib discontinued therapy due to grade 3 or higher pneumonitis. Two of the three patients with interstitial lung disease had previous immunotherapy. One patient who never had previous immunotherapy discontinued crizotinib plus osimertinib due to grade 2 nausea and diarrhea. Toxicity assessment may be incomplete due to the nature of retrospective chart review (Supplementary Table 4).

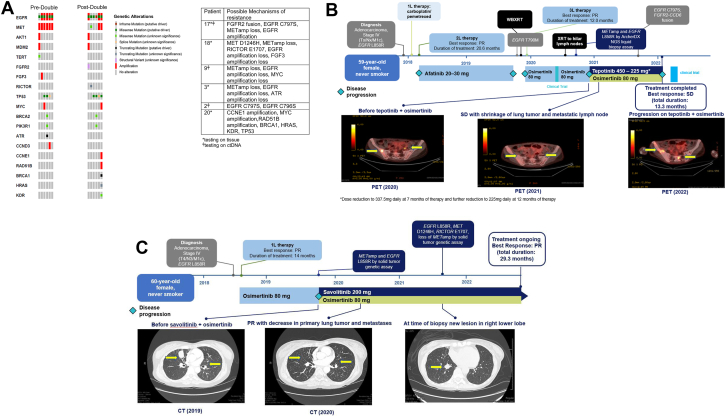

Acquired Resistance Mechanisms

On progression on dual EGFR-MET inhibition, six patients completed NGS testing and FISH analysis (Fig. 2A). Resistance mechanisms were diverse. Patient 17 gained FGFR2 fusion along with EGFR C797S and loss of METamp. Patient 18 acquired MET D1246H and RICTOR E1707 frameshift with concurrent loss of METamp, loss of EGFR amplification, and loss of FGF3 amplification. Patient 9 had loss of METamp, loss of EGFR amplification, and loss of MYC amplification. Patient 3 developed loss of METamp, loss of EGFR amplification, and loss of ATR mutation. Patient 2 had EGFR C797S concurrent with EGFR C796S. Patient 20 developed CCNE1 amplification, MYC amplification, RAD51B amplification, BRCA1 point mutation, HRAS point mutation, KDR point mutation, and TP53.

Figure 2.

Resistance mechanisms in patients whose tumor progressed on EGFR-MET inhibition therapy. (A) Co-mutation plot for six patients pretreatment and post-treatment. (B) Treatment history and timing of events of the patient with acquired FGFR2 fusion EGFR C797S. (C) Treatment history and timing of events of the patient with acquired MET D1246H. 1L, first line; 2L, second line; 3L, third line; ctDNA, circulating tumor DNA; METamp, MET amplification; NGS, next-generation sequencing; PET, positron emission tomography; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; WBXRT, whole-brain radiotherapy; XRT, radiotherapy.

Acquired EGFR Mutation

A 59-year-old female (patient 17), never-smoker, was diagnosed with having metastatic adenocarcinoma of the right lung and bone metastases with EGFR L858R mutation in 2017. She received carboplatin and pemetrexed before switching to afatinib and achieved partial response. She developed disease progression including new brain metastases after more than 20 months of afatinib. EGFR T790M was detected, and the patient received whole brain radiation and osimertinib 80 mg daily. Partial response was found, but she eventually developed disease progression after 12 months. She then received an investigational systemic treatment with T cell therapy. METamp was detected by ctDNA. She initiated tepotinib 450 mg daily plus osimertinib 80 mg in 2020. Her tepotinib dose was reduced to 337.5 mg daily due to nausea and vomiting and subsequently to 225 mg daily. Best response on therapy was stable disease before disease progression after 12 months. A repeat biopsy from the right lower lobe revealed new FGFR2-CCD6 fusion. Furthermore, new EGFR C797S was found on ctDNA with a variant allelic frequency (VAF) of 5% in addition to persistent EGFR L858R (VAF 50.4%) and T790M (VAF 8%). EGFR C797S and METamp were not detected on tissue NGS. She received reirradiation to the right hilum and subsequently another investigational therapy with fourth-generation EGFR inhibitor during the dose-escalation phase (Fig. 2B).

Acquired MET Mutation

A 60-year-old female (patient 18), never-smoker, was diagnosed with having EGFR L858R-mutated lung adenocarcinoma with malignant pleural effusion in 2018. She had partial response to first-line osimertinib 80 mg daily but developed disease progression after 14 months. A repeat tissue biopsy revealed METamp on NGS and EGFR amplification in addition to EGFR L858R (VAF 77%). She then received osimertinib 80 mg daily plus savolitinib 600 mg daily on a clinical trial. Primary targeted lesion revealed partial response after 4 months of therapy. After 11 months of double TKI, she developed a new lesion in the right lower lobe. Biopsy confirmed lung adenocarcinoma with tissue NGS revealing EGFR L858R (VAF 40%), MET D1246H (VAF 33%), RICTOR E1707 frameshift (VAF 18%), and loss of METamp. She was scheduled to receive palliative radiation to the new lesion and continued double TKI therapy. She has been on double TKI treatment for more than 29 months (Fig. 2C).

Discussion

Dual EGFR-MET inhibition is a promising treatment strategy in EGFR-mutant metastatic NSCLC with resistance to EGFR TKI mediated by METamp. The TATTON trial revealed ORR of 33% to 67% with osimertinib plus savolitinib in different cohorts of patients who had EGFR TKI-resistant MET-amplified NSCLCs.4 The ORCHARD trial’s osimertinib plus savolitinib arm also revealed an ORR of 41% in patients who received osimertinib as their first-line therapy.5 Most recently, the SAVANNAH trial with combination of osimertinib plus savolitinib provided an ORR of 32% in patients who are METamp positive on FISH more than or equal to 5 GCN and IHC50+ with a median progression free survival of 5.3 months after progression on osimertinib.7 The INSIGHT 2 trial with osimertinib plus tepotinib observed an ORR of 54.5% in patients who are MET amplified on FISH in tissue biopsy after progression on osimertinib.6 Both SAVANNAH and INSIGHT 2 were large prospective studies, revealing encouraging efficacy with the double TKI approach. Our study is a retrospective analysis; nonetheless, it reported similar response rate (35% by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors and 65% by clinician judgment) with expected toxicities, which suggested the use of dual EGFR-MET inhibition in real world could be used in patients with EGFR-mutated and MET-amplified lung cancers.

Understanding resistance mechanisms to therapy is critical to stratify patients and provide the most appropriate next-line options to patients. Resistance data from the large clinical trials are not yet available; therefore, we evaluated resistance mechanisms in our retrospective analysis. We found that tumors were able to escape double TKI suppression by developing resistance to either one of the TKIs. In our cohort of six patients with NGS profiling, resistance to MET inhibitor, such as D1246H mutation,8, 9, 10, 11 and resistance to EGFR inhibitor, such as C797S and C796S,3,12 were observed. Acquired oncogenic fusions, such as FGFR fusions, were known resistance mechanisms to osimertinib, and we identified one case with acquired FGFR2 fusion.3 Interestingly, the FGFR2 fusion tumor had heterogeneity with detection of C797S in the blood but not on tissue NGS. In our cohort, METamp loss at the time of progression was also frequently observed. Although it is uncertain that loss of METamp can serve as a sole mechanism of resistance to double TKI resistance, the high frequency of loss of METamp could be related to possible escape mechanisms to target therapies. Our study revealed the suitable role for plasma NGS in detecting resistance mechanisms on disease progression.

Taken together, our real-world retrospective analysis revealed that double EGFR-MET TKI treatment can be effective and safe for patients with EGFR-mutant, MET-amplified lung cancer after progression on osimertinib. Plasma NGS testing plays a critical role in assessing molecular resistance mechanisms as ctDNA is a noninvasive approach allowing simultaneous detection of potentially heterogeneous resistance and guiding treatment selection. Either acquired MET resistance mutation or EGFR resistance mutation or oncogenic fusion could emerge as resistance mechanisms to double TKI treatment.

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement

Kaiwen Wang: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Visualization.

Robyn Du: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—review and editing, Visualization.

Sinchita Roy-Chowdhuri: Resources, Data curation, Writing—review and editing.

Ziping T. Li: Formal analysis.

Lingzhi Hong: Project administration.

Natalie Vokes: Data curation.

Yasir Y. Elamin: Data curation.

Celyne Bueno Hume: Data curation.

Ferdinandos Skoulidis: Data curation.

Carl M. Gay: Data curation, Writing—review and editing.

George Blumenschein: Data curation.

Frank V. Fossella: Data curation.

Anne Tsao: Data curation.

Jianjun Zhang: Data curation, Writing—review and editing.

Niki Karachaliou: Writing—review and editing.

Aurora O’Brate: Writing—review and editing.

Claudia-Nanette Gann: Writing—review and editing.

Jeff Lewis: Supervision.

Waree Rinsurongkawong: Supervision.

Jack Lee: Supervision.

Don Lynn Gibbons: Supervision.

Ara A. Vaporciyan: Supervision.

John V. Heymach: Supervision.

Mehmet Altan: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology.

Xiuning Le: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing—original draft, Supervision.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Vokes received funding from Mark Foundation Damon Dunyon Physician Scientist Award. Dr. Le received Damon Dunyon Clinical Investigator Award and V Foundation Clinical Investigator Award. The authors thank the ORCHARD study team and committee member and the INSIGHT 2 study team and committee member for sharing the patients’ treatment histories.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Wang received consulting fees from BluPrint Oncology. Dr. Vokes received honoraria from Sanofi; participated on advisory board or data safety monitoring board for Regeneron, Oncocyte, Sanofi, and Lilly. Dr. Elamin received research grants from Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Takeda, Xcovery, Eli Lilly, Elevation Oncology, and Turning Point Therapeutics to institution; received consulting fees from Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, and Turning Point Therapeutics; and received support for meetings and/or travel from Eli Lilly. Dr. Skoulidis received research grants from Revolution Medicines, Mirati Therapeutics, Pfizer, Merck, Amgen, and Novartis to institution; received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Amgen, Novartis, BeiGene, Guardant Health, Bergen Bio, Navire Pharma, Tango Therapeutics, Calithera Biosciences, Intellisphere LLC, and Medscape LLC; received honoraria from VSPO McGill Universite de Montreal and RV Mais Promocao Eventos LTDS; received support for meetings and/or travel from Amgen, Tango Therapeutics, and Dava Oncology; participated on advisory board for AstraZeneca, Novartis, BeiGene, Guardant Health, Bergen Bio, and Calithera Biosciences; and had stock or stock options in Moderna and BioNTech SE. Dr. Gay received research grant from AstraZeneca; received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, G1 Therapeutics, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Monte Rosa Therapeutics; received honoraria from AstraZeneca and BeiGene; received support for meetings and/or travel from Dava Oncology; participated on data safety monitoring board or advisory board for AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, G1 Therapeutics, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Blumenschein received research grants from Amgen, Bayer, Adaptimmune, Exelixis, Daiichi Sankyo, GlaxoSmithKline, Immatics, Immunocore, Incyte, Kite Pharma, Macrogenics, Torque, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Genentech, MedImmune, Merck, Novartis, Roche, Xcovery, Tmunity Therapeutics, Regeneron, BeiGene, Repertoire Immune Medicines, and Verastem to institution; and received consulting fees from AbbVie, Adicet, Amgen, Ariad, Bayer, Clovis Oncology, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Instil Bio, Genentech, Gilead, Eli Lilly, Janssen, MedImmune, Merck, Novartis, Roche, Tyme Oncology, Xcovery, Virogin Biotech, and Maverick Therapeutics. Dr. Tsao received research funding from Ariad, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Millennium, Polaris, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Epizyme, Merck, Novartis, and Seattle Genetics to institution; received consulting fees from Ariad, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Merck, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, EMD Serono, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Roche. Dr. Zhang received research grants from Merck and Novartis to institution; received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Geneplus, Capital Medical University, Johnson & Johnson/Janssen, and Novartis; received honoraria from Roche, Sino-USE Biomedical platform, Geneplus, Origimed, Innovent Biologics, CancerNet, and Zhejiang Cancer Hospital; and received support for meeting and/or travel from Zhejiang Cancer Hospital and Innovent Biologics. Dr. Karachaliou is an employee of Merck Healthcare KGaA/EMD Serono. Dr. O’Brate is an employee of Merck Healthcare KGaA/EMD Serono. Dr. Gann is an employee of Merck Healthcare KGaA/EMD Serono. Dr. Gibbons received research funding from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, NGM Biopharmaceuticals, Ribon Therapeutics, Mirati Therapeutics, and Astellas to institution; received consulting fees from 4D Pharma, Onconova, Menarini Richerche, Eli Lilly, and AstraZeneca; held leadership role in Rexanna’s Foundation for Fighting Lung Cancer. Dr. Heymach received research grants from AstraZeneca, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, and GlaxoSmithKline to institution; held intellectual property for treatment of EGFR and HER exon20 mutations between MD Anderson, Spectrum, and myself; received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Guardant Health, Takeda, Genentech/Roche, Catalyst Biotech, Novartis, BrightPath Biotherapeutics, Nexus Health Systems, Kairos Ventures, Leads Biolabs, Roche, Hengrui Pharmaceutical, GlaxoSmithKline, EMD Serono, Eli Lilly, Sanofi/Aventis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Foundation Medicine, Mirati Therapeutics, Janssen, and Pneuma Respiratory; held stocks or stock options in Cardinal Spine and Bio-Tree; and held leadership role in Rexanna’s Foundation for Fighting Lung Cancer. Dr. Altan received research funding from Genentech, Nektar Therapeutics, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Jounce Therapeutics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Adaptimmune, Shattuck Lab, and Gilead to institution; received consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Nektar Therapeutics, and Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer; participated on data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Nanobiotix-MDA Alliance and Hengenix. Dr. Le received research funding from Eli Lilly, Regeneron, ArriVent, Teligene, and Boehringer Ingelheim to institution; received consulting fees from EMD Serono, AstraZeneca, Spectrum, Hengrui Therapeutics, Novartis, Janssen, Blueprint, Sensi, and AbbVie; and received support for meetings and/or travel from Spectrum and Merck (EMO Serono). The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Cite this article as: Wang K, Du R, Roy-Chowdhuri S, et al. Brief report: clinical response, toxicity, and resistance mechanisms to osimertinib plus MET inhibitors in patients with EGFR-mutant MET-amplified NSCLC. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2023;4:100533.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of the JTO Clinical and Research Reports at www.jtocrr.org and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtocrr.2023.100533.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Tan A.C., Tan D.S.W. Targeted therapies for lung cancer patients with oncogenic drive molecular alterations. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:611–625. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soria J., Ohe Y., Vansteenkiste J., et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:113–125. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leonetti A., Sharma S., Minari R., Perego P., Giovannetti E., Tiseo M. Resistance mechanisms to Osimertinib in EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2019;121:725–737. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0573-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartmaier R., Markovets A.A., Ahn M.J., et al. Osimertinib + savolitinib to overcome acquired MET-mediated resistance in epidermal growth factor receptor-mutated, MET-amplified non-small cell lung cancer: TATTON. Cancer Discov. 2023;13:98–113. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-22-0586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu H.A., Ambrose H., Baik C., et al. ORCHARD Osimertinib + savolitinib interim analysis: a biomarker directed phase II platform study in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer whose disease has progressed on first-line osimertinib. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(suppl):S949–S1039. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2021.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazieres J., Kim T.M., Lim B.K., et al. LBA52 tepotinib + osimertinib for EGFRm NSCLC with MET amplification (METamp) after progression on first-line (1L) osimertinib: initial results from the INSIGHT2 study. Ann Oncol. 2022;33(suppl 7):S808–S869. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahn M.J., De Marinis F., Bonanno L., et al. MET biomarker-based preliminary efficacy analysis in SAVANNAH: savolitinib + osimertinib in EGFRm NSCLC post-osimertinib. J Thorac Oncol. 2022;17:s469–s470. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang J., Chen H., Wang Z., et al. Osimeritnib and cabozantinib combinatorial therapy in an EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma patient with multiple MET secondary-site mutations after resistance to crizotinib. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:e49–e53. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li L., Qu J., Heng J., et al. A large real-world study on the effectiveness of the combined inhibition of EGFR and MET in EGFR-mutant advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(suppl 15) doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.722039. 9043–9043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piper-Vallillo A.J., Halber B.T., Rangachari D., Kobayashi S.S., Costa D.B. Acquired resistance to Osimertinib plus savolitinib is mediated by MET-D1228 and MET-Y1230 mutations in EGFR mutated MET amplified lung cancer. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2020;1 doi: 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2020.100071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim S.M., Yang S.D., Lim S., Shim H.S., Cho B.C. Heterogeneity of acquired resistance mechanisms to Osimertinib and savolitinib. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2021;30 doi: 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2021.100180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robichaux J.P., Le X., Vijayan R.S.K., et al. Structure-based classification predicts drug response in EGFR-mutant NSCLC. Nature. 2021;597:732–757. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03898-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.