Highlights

-

•

A 73-year-old woman, who had been suffering from secondary progressive MS for decades and had not received any immunomodulatory medication, presented with status epilepticus, followed by non-convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE), and subsequently experienced neuropsychiatric and vegetative symptoms.

-

•

Diagnostics (EEG, MRI, CSF analysis, clinical examination) revealed NMDAR encephalitis.

-

•

Treatment with high-dose IV prednisolone led to a significant clinical improvement.

-

•

The association between NMDAR encephalitis and multiple sclerosis is still largely unclear and only a few cases, typically in younger patients, have yet been reported.

Keywords: Multiple Sclerosis, Autoimmune encephalitis, NMDAR encephalitis, Anti-N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptor Encephalitis, Demyelinating disease

Abstract

Anti-NMDA receptor (Anti-NMDAR) encephalitis is an autoimmune disease that presents with diverse symptoms. Since literature is scarce on the overlap with multiple sclerosis (MS), this report aims to elucidate the distinctive clinical presentation and diagnostic challenges of anti-NMDAR encephalitis in MS patients.

A 73-year-old woman with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis, after experiencing status epilepticus and subsequent non-convulsive status epilepticus, presented with neuropsychiatric symptoms and autonomic nervous dysfunction. Notably, the patient had not received any immunomodulatory therapy. The clinical picture together with diagnostics (MRI, EEG, cerebro-spinal fluid) let us suspect HSV-meningoencephalitis and empirically treat the patient with IV acyclovir. Due to a lack of clinical improvement, we reconsidered the diagnosis and found the diagnostic criteria for autoimmune encephalitis to be met. Antibodies in blood and CSF were positive and we diagnosed the patient with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. The patient responded well to IV prednisolone treatment, leading to a stable outcome in a six-month follow-up.

This case highlights the difficulties in diagnosing anti-NMDAR encephalitis in patients with multiple sclerosis. The presence of epileptic seizures can serve as a crucial diagnostic indicator to distinguish between an MS relapse and an overlapping disease. Compared to patients with other demyelinating diseases, patients with overlapping MS appear to have a higher risk of motor seizures.

Introduction

Both anti-NMDAR encephalitis and multiple sclerosis (MS) are autoimmune disorders of the central nervous system. Individuals of any age and sex can be affected, but there is a higher prevalence in younger females for both conditions.[1], [2] While in many cases the etiology remains unclear, anti-NMDAR encephalitis can occur as a paraneoplastic phenomenon or follow viral infections.[3], [4].

In recent years, there has been an increasing number of reports emphasizing the overlap between the encephalitis and demyelinating disorders such as MOGAD (MOG Antibody Disease) and NMOSD (Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder), and a shared immunological pathomechanism is suspected.[5] In MS patients, this remains a relatively rare and less studied phenomenon with to date only 16 cases published.[6].

Diagnosing anti-NMDAR encephalitis can be challenging, and despite known diagnostic criteria, misdiagnoses still occur.[7] Given the sometimes-similar symptoms (movement and speech disorders, neuropsychiatric symptoms), diagnosis can be even more challenging in MS patients. Epileptic seizures on the other hand raise suspicion of encephalitis.[8], [9] In this report, we present the case of a female MS patient who was hospitalized after experiencing status epilepticus.

Methods

We present a case report according to the CARE Case Reporting Guidelines. The literature research was carried out using the PubMed database. The search terms used were “NMDAR encephalitis”, “N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor”, “multiple sclerosis”, “demyelinating disease” “neuropsychiatric syndromes” and combinations. We limited the literature used to English, peer-reviewed publications with full-text availability.

Ethical Statement.

Description of the case and presentation of the images takes place with the patient’s informed consent. The consent was granted by the husband as the patient's legally authorized representative.

Case report

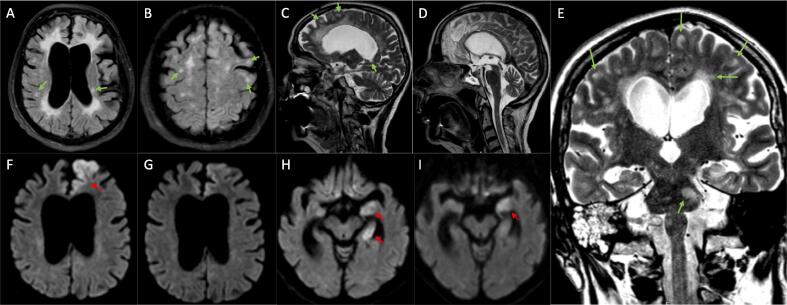

We present the case of a 73-year-old Caucasian woman with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS). The patient had been diagnosed with MS decades ago, but the corresponding MRI images and written records were unavailable due to various changes in healthcare providers. However, we performed MRI and the findings were consistent with advanced MS (please see Fig. 1 A-E) and, along with the application of the 2017 McDonald criteria, supported the diagnosis of MS. Hence, she wasn’t tested for anti-MOG and anti-AQP4 antibodies.[10] The patient was bedridden due to MS-related spastic tetra-paresis. According to information provided by the husband, there were presumed mild chronic psycho-organic alterations, including impaired memory and sleep disturbances. To the best of our knowledge, the patient had not received any immunomodulating therapy. There was no history of epileptic seizures. We had previously encountered the patient two years ago when she was hospitalized for left-sided idiopathic peripheral facial palsy, which resulted in a residual Bell phenomenon. Before admission, she was taking retarded fampridine 10 mg/day, baclofen 10 mg/day, and opipramol 100 mg/day.

Fig. 1.

Bihemispheric, subcortical, and juxtacortical FLAIR (Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery) (A, B) and T2 (C, D, E) hyperintensities with multiple disseminated ovoid lesions, partially located in association with the corpus callosum, periventricular or in the pons (E) (exemplarily marked with green arrows). The partially visualized cervical myelon (D) shows no abnormalities. (A) shows brain atrophy with significant enlargement of the ventricles and subarachnoid spaces. Brain Diffusion-Weighted Imaging with (F) areal restricted diffusion of the left frontal lobe, particularly the parasagittal cortical zone before and (G) 13 days after IV prednisolone treatment. (H) Restricted diffusion of the left medial temporal lobe before and (I) 13 days after IV prednisolone treatment (marked with red arrows). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The woman was hospitalized following status epilepticus with unknown onset bilateral tonic-clonic epileptic seizures that lasted approximately 50 min and were terminated by the emergency medical services via 2,5 mg lorazepam (PO) and 5 mg of diazepam (IV), we then initiated anticonvulsant therapy with levetiracetam. Subsequently, she entered a pre-comatose state, exhibited forced head and eye deviation to the right side as well as an ongoing proximally accentuated myoclonus of her left arm, prompting her admission to our Intermediate Care Unit (ICU). The patient, according to her husband and the home care service nurse, did not exhibit any prodromal symptoms such as signs of infection or abnormal behavior prior to admission. Initial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis and native head CT showed no pathology beyond the typical changes associated with MS, such as brain atrophy and a pathological IgG index of 1.23 [reference: <0.7]).

We conducted serial resting EEGs. The initial EEG showed generalized background slowing with continuous epileptic activity in the left hemisphere, predominantly in the frontoparietal region. However, there was no clear seizure-specific evolution observed. Taking into account the EEG findings and the clinical context, we diagnosed the patient with non-convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) based on the Salzburg criteria.[11], [12] Hence, the patient was administered IV valproate (VPA; 1,6g/d) and diazepam. After regaining consciousness, the patient exhibited neuropsychiatric symptoms, including repetition of phrases in a palilalia-like manner, pseudobulbar affect with episodes of pathological laughing and crying, as well as a significant impairment of concentration and memory. Subsequent EEGs revealed lateralized periodic discharges originating from the left hemisphere (exemplarily shown in Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Basal EEG in longitudinal bipolar montage five days after hospitalization and administration of levetiracetam, valproate (VPA), and diazepam, showing lateralized periodic discharges of the left hemisphere. The finding points to acute cortical damage in the left hemisphere and is associated with an increased probability of epileptic seizures. Filter: 70 Hz.

Due to persistent symptoms and the emergence of new vegetative symptoms such as sub-febrile temperature, hyperhidrosis, and blood pressure fluctuations with pleural effusions, CSF analysis was repeated, showing a lymphocytic pleocytosis of 11 cells/µl. DWI (Diffusion-Weighted Imaging) revealed restricted diffusion in left brain areas including the frontal and temporal lobe, hippocampus, and corpus amygdaloideum (Fig. 1 F, H), while T2 and FLAIR (Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery) weighted images showed spatial dissemination of bihemispheric, pontine and cerebellar (not shown) subcortical and juxtacortical ovoid lesions, typical with MS (Fig. 1 A-E).

We considered HSV-meningoencephalitis and initiated an empirical antiviral treatment with intravenous acyclovir, and the patient showed initial clinical improvement, but neither the virus nor its surrogate parameters could be found. We then suggested autoimmune encephalitis and found the diagnostic criteria to be met. Hence, the patient’s samples were assessed for antineuronal antibodies (Yo, Hu, Ri, Ma1, Ma2, CV2, Amphiphysin) via IgG-immunoblotting, and anti-neuropil antibodies (NMDAR, GABARB1, AMPAR1, AMPAR2, CASPR2, LGl1, DPPX) in a cell-based assay using fixed HEK-cells (F-CBA) followed by IF (Immunofluorescence) Staining and tested positive for anti-NMDAR antibodies in both serum and CSF (titers: 1:10). No neoplasia or major infection (treponema, HIV) could be detected via CT scans, gynecological consultations, and blood tests.[13].

The patient was treated with high-dose IV prednisolone (1000 mg/day for five days) and showed rapid recovery within days, although palilalia and impaired memory persisted. These clinical findings correlated with sustained lesions of the corpus amygdaloideum observed in MRI, while the frontal lesions showed a significant response to the prednisolone treatment in a follow-up MRI conducted 13 days later (please see Fig. 1 G, I).[14] EEG also indicated recovery. Medication was adjusted before hospital discharge, and the dose of prednisolone was gradually tapered. We discontinued the use of fampridine as its benefits in bedridden patients are not evident, and there are even indications of possible epileptogenic side effects.[15] We continued administering levetiracetam (3 g/day) and recommended gradual tapering and eventual discontinuation. At a six-month follow-up, the patient and her husband reported sustained improvement.

Discussion

We presented the case of a 73-year-old woman who had SPMS for decades and developed anti-NMDAR encephalitis with status epilepticus as the disease’s first hallmark.

Epileptic seizures are a cardinal symptom of autoimmune encephalitis and have also been observed in patients with overlapping MS, whereas patients with MS alone only have a slightly increased risk of experiencing epileptic seizures.[9] However, motor seizures have not yet been described in patients with other demyelinating diseases that overlap with anti-NMDAR encephalitis, suggesting that MS patients may be more prone to motor seizures, or that other demyelinating disorders may provide protective factors against such seizures.[8], [16] Neuropsychiatric syndromes occur quite frequently in MS patients, such as pseudobulbar affect in around 10%, and impaired memory in about 40–65% of cases.[17] Even the prevalence rate of psychosis in MS patients is two to three times higher than in the general population.[18] Therefore, physicians may just as well attribute neuropsychiatric symptoms to MS rather than considering other possible causes, which could result in anti-NMDAR encephalitis being overlooked in MS patients.[19], [20], [21] In some cases, anti-NMDAR encephalitis occurred during the relapse of a demyelinating disorder or was mistaken for one.[5], [22] However, our patient presented with status epilepticus, which is not typical for an MS relapse, and therefore was investigated for a disease other than MS.

<50% of patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis alone, as well as those with overlapping MOGAD or NMOSD, exhibit MRI abnormalities in the brain. In contrast, almost all MS patients with overlapping anti-NMDAR encephalitis show abnormalities, which are often reported as T2/FLAIR hyperintensities and rarely as restricted diffusion in DWI.[16] Typically affected regions are the frontal and medial temporal lobe, including the hippocampus and corpus amygdaloideum, as depicted in Fig. 1 F-I.[14], [23] In EEG, non-specific diffuse slowing, focal abnormalities, and even epileptiform discharges are more commonly observed, whereas disease-specific patterns like extreme delta brush are less likely to appear.[23] Unfortunately, the EEG findings of patients with overlapping MS have overall been neglected in previous reports, leaving potential similarities or peculiarities unclear. The findings of nine patients however mainly include normal or unspecific mild abnormalities, such as diffuse slowing. Focal abnormalities were found in three patients while extreme delta brush was only observed in one patient.[6].

There are no existing guidelines specifying an ideal therapy for anti-NMDAR encephalitis in patients with overlapping demyelinating disorders. While these patients are thought to be less responsive to first-line immunotherapy with steroids, our patient responded well to IV prednisolone treatment.[5] In previous cases, three patients received no immunotherapy at all, and three patients received monotherapy with IV methylprednisolone (IVMP). In some cases, IVMP was combined with IV Immunoglobulin (IVIG), and some patients were administered immunotherapeutic agents like mitoxantrone, rituximab, teriflunomide, bortezomib, daclizumab or mycophenolate mofetil. Plasmapheresis was carried out in four cases.[6].

Patients with overlapping demyelinating diseases are thought to develop mild courses of anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Still, outcomes are extremely different, and given the diverse constellations and therapeutic approaches, they can hardly be compared with one another. Lower antibody titers are in general considered to predict a better outcome. This is consistent with our patient's titers and outcome, and she was able to describe a stable situation in a six-month follow-up.[24].

We already mentioned that anti-NMDAR encephalitis may affect patients of any age (<1–85) while the median age of onset is 21 years. In patients with overlapping MS, the average age of onset is slightly higher (31) and our patient’s age deviates even more significantly from the typically younger patient population.[6], [25], [26] In some cases, anti-NMDAR encephalitis occurs before MS, while in the majority of cases, the encephalitis occurs during the course or even a relapse of MS, suggesting a potential triggering effect of MS on anti-NMDAR encephalitis.[22] This might be due to demyelination exposing neuronal antigens, which in turn trigger an intrathecal immune response. This could explain the higher average age of onset in patients with overlapping diseases, as the process of demyelination takes time for the release of neuronal antigens. This theory aligns well with our patient’s age and state of demyelination (please see Fig. 1 A-E).[6] There are known triggers for anti-NMDAR encephalitis, such as antecedent HSV meningoencephalitis, or neoplasia like ovarian teratoma. However, an underlying malignancy does not seem to be the case in patients with overlapping MS which further underlines an independent immunological link.[4], [16] It has been shown that immunomodulatory therapy with natalizumab may suppress CD138 + plasma cells. In the case of cessation, levels of the anti-NMDAR antibody-producing plasma cells will rise. This facilitates their entry into the CNS and the effect appears to be occurring in MS but not in other demyelinating diseases, making it an exclusive risk factor for MS patients. In the past, this has already led to anti-NMDAR encephalitis in a patient with RRMS.[22], [27], [28] However, this does not apply to our patient who did not receive any immunomodulatory agents.

Anti-NMDAR encephalitis in patients with other demyelinating diseases is well-reported and has already been investigated in larger studies. Titulaer and colleagues tested 691 patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis for anti-MOG- and anti-AQP4 antibodies and found 23 of the patients to have antibody-positive demyelinating syndromes. Since oligodendrocytes express NMDA receptors, anti–MOG antibodies are considered to play a role in the pathogenesis of anti–NMDAR encephalitis. However, the authors found that NMOSD in patients with anti–NMDAR encephalitis occurs about 200 times more frequently than expected in the general population (4/691 patients) and that it also is the most frequent demyelinating disease that overlaps with anti–NMDAR encephalitis. Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether the link between MS and anti-NMDAR encephalitis holds the same importance, as there have been only a few reported cases so far and there is a lack of larger studies.[5].

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patient and her husband for their collaboration by participating in this publication. The authors thank PD Dr. Lisa Adams for reviewing the manuscript.

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr. Wibke Johannis for her valuable support in conducting the antibody testing.

Funding

A.K., R.A., and T.Z received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

André Kachlmeier, Email: Kachlmeier@posteo.de.

Rolf Adams, Email: Adams@koeln.de.

Tobias Zahalka, Email: Tobias.Zahalka@khs-frechen.de.

References

- 1.Koch-Henriksen N., Sørensen P.S. The changing demographic pattern of multiple sclerosis epidemiology. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(5):520–532. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dalmau J., Armangué T., Planagumà J., Radosevic M., Mannara F., Leypoldt F., et al. An update on anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis for neurologists and psychiatrists: mechanisms and models. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(11):1045–1057. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30244-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalmau J., Tüzün E., Wu H.-Y., Masjuan J., Rossi J.E., Voloschin A., et al. Paraneoplastic anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis associated with ovarian teratoma. Ann Neurol. 2007;61(1):25–36. doi: 10.1002/ana.21050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armangue T., Leypoldt F., Málaga I., Raspall-Chaure M., Marti I., Nichter C., et al. Herpes simplex virus encephalitis is a trigger of brain autoimmunity. Ann Neurol. 2014;75(2):317–323. doi: 10.1002/ana.24083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Titulaer M.J., Höftberger R., Iizuka T., Leypoldt F., McCracken L., Cellucci T., et al. Overlapping demyelinating syndromes and anti–N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis. Ann Neurol. 2014;75(3):411–428. doi: 10.1002/ana.24117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu P., Yan H., Li H., Zhang C., Li Y. Overlapping anti-NMDAR encephalitis and multiple sclerosis: A case report and literature review. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1088801. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1088801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flanagan E.P., Geschwind M.D., Lopez-Chiriboga A.S., Blackburn K.M., Turaga S., Binks S., et al. Autoimmune Encephalitis Misdiagnosis in Adults. JAMA Neurol. 2023;80(1):30. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taraschenko O., Zabad R. Overlapping demyelinating syndrome and anti-N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor encephalitis with seizures. Epilepsy Behav Rep. 2019;12 doi: 10.1016/j.ebr.2019.100338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuß F., von Podewils F., Wang Z.I., Süße M., Zettl U.K., Grothe M. Epileptic seizures in multiple sclerosis: prevalence, competing causes and diagnostic accuracy. J Neurol. 2021;268(5):1721–1727. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10346-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson A.J., Banwell B.L., Barkhof F., Carroll W.M., Coetzee T., Comi G., et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162–173. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30470-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leitinger M., Trinka E., Gardella E., Rohracher A., Kalss G., Qerama E., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Salzburg EEG criteria for non-convulsive status epilepticus: a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(10):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trinka E., Cock H., Hesdorffer D., Rossetti A.O., Scheffer I.E., Shinnar S., et al. A definition and classification of status epilepticus–Report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2015;56(10):1515–1523. doi: 10.1111/epi.13121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graus F., Titulaer M.J., Balu R., Benseler S., Bien C.G., Cellucci T., et al. A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(4):391–404. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00401-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McHattie A.W., Coebergh J., Khan F., Morgante F. Palilalia as a prominent feature of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis in a woman with COVID-19. J Neurol. 2021;268(11):3995–3997. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10542-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Etemadifar M., Saboori M., Chitsaz A., Nouri H., Salari M., Khorvash R., et al. The effect of fampridine on the risk of seizure in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;43:102188. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang S., Yang Y., Liu W., Li Z., Li J., Zhou D. Clinical Characteristics of Anti-N-Methyl-d-Aspartate Receptor Encephalitis Overlapping with Demyelinating Diseases: A Review. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.857443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghaffar O., Chamelian L., Feinstein A. Neuroanatomy of pseudobulbar affect : a quantitative MRI study in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2008;255(3):406–412. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0685-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilberthorpe T.G., O'Connell K.E., Carolan A., Silber E., Brex P.A., Sibtain N.A., et al. The spectrum of psychosis in multiple sclerosis: a clinical case series. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:303–318. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S116772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jongen P.J., ter Horst A.T., Brands A.M. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Minerva Med. 2012;103(2):73–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy R., O’Donoghue S., Counihan T., McDonald C., Calabresi P.A., Ahmed M.AS., et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(8):697–708. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-315367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson L.L., Pollak T.A., Blackman G., Thornton M., Moran N., David A.S. The Psychiatric Phenotype of Anti-NMDA Receptor Encephalitis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;31(1):70–79. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.17120343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang Y., Wang Q., Zeng S., Zhang Y., Zou L., Fu X., et al. Case Report: Overlapping Multiple Sclerosis With Anti-N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptor Encephalitis: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Front Immunol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.595417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen L., Wang C. Anti-NMDA Receptor Autoimmune Encephalitis: Diagnosis and Management Strategies. Int J Gen Med. 2023;16:7–21. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S397429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gresa-Arribas N., Titulaer M.J., Torrents A., Aguilar E., McCracken L., Leypoldt F., et al. Antibody titres at diagnosis and during follow-up of anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(2):167–177. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70282-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Titulaer M.J., McCracken L., Gabilondo I., Armangué T., Glaser C., Iizuka T., et al. Treatment and prognostic factors for long-term outcome in patients with anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis: an observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):157–165. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70310-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Y., Ren G., Ren J., Shan W., Han X., Lian Y., et al. The Association Between Age and Prognosis in Patients Under 45 Years of Age With Anti-NMDA Receptor Encephalitis. Front Neurol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.612632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stuve O., Cravens P.D., Frohman E.M., Phillips J.T., Remington G.M., von Geldern G., et al. Immunologic, clinical, and radiologic status 14 months after cessation of natalizumab therapy. Neurology. 2009;72(5):396–401. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327341.89587.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fleischmann R., Prüss H., Rosche B., Bahnemann M., Gelderblom H., Deuschle K., et al. Severe cognitive impairment associated with intrathecal antibodies to the NR1 subunit of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor in a patient with multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(1):96. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]