1. Introduction

One important aspect of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is financial protection when receiving medical care [[1], [2], [3]]. However, on a global level, catastrophe health expenditure rose by 5.3% for 100 million to 200 million people at a threshold of 25% until 2015 [3]. Out-of-pocket payment (OOP) has been the primary method of financing the health system in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) even though other prepayment options are available [4,5]. In sub-Saharan Africa, OOP accounts for 40% of the total health expenditure placing a significant financial burden on several communities and limiting access to healthcare services at the point of care [5]. In addition, the health systems of LMIC are faced with major challenges, including high OOP, poor public healthcare service quality, and inadequate prepayment coverage [6,7]. Communities in Ghana experienced severe financial difficulty as a result of OOP spending, which accounted for 37% of all health spending in the last decade [8,9]. According to Sarkodie, Ghanaians sometimes spend on outpatient consultations, admissions, drugs, etc., even though they have valid national health insurance scheme cards (NHIS) [10]. This is to underscore the fact that, some healthcare providers demand payment from patients though Ghana does not operate a co-payment system of financing health. It is also important to note that, OOP among non-NHIS card-bearing members is even higher as compared to those who have the NHIS card [10]. The burden of OOP on Ghanaians is collaborated by Akweongo and colleagues, who stated that valid NHIS card-bearing members, accessing healthcare in accredited health facilities still make OOP payments for some consultations and medicines that were covered by NHIS [11]. Continuous OOP payment can impede the objectives of universal health coverage and goal three (3) of the United Nations sustainable development goals (UN SDG 3), which is aimed at reducing poverty and health inequalities. According to Sataru and colleagues, as a result of inadequacies in financial risk protection coverage, the incidence and risk of financial catastrophe continued to be unreasonably higher among the poorest households compared to rich households [12]. To mobilize resources for health, the World Health Organization (WHO) suggests switching from direct OOP to prepayment methods and pooling risks through healthcare financing strategies [2]. The use of telemedicine in the provision of health services can reduce household catastrophe health expenditures [13].

The WHO defines telemedicine as "healthcare service delivery by healthcare professionals who use Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) to exchange valid information for disease prevention, diagnosis, treatment, research, and evaluation, as well as for healthcare providers' education." This is interesting given the need to improve health at the individual and community levels [14]. It is possible to say that, despite its challenges, the 21st century offered a significant number of opportunities for the transformation of the healthcare system. These opportunities include; the potential of using telemedicine to improve access to care, reduce patient travel and waiting times, reduce unnecessary emergency department visits, and reduce medication misuse [13]. Telemedicine provides a platform for interaction between patients and practitioners and monitoring vital signs and symptom evaluation [15].

Chronic diseases like asthma, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) account for 11.1 million disability-adjusted life years, or 7% of the total disability-adjusted life years in high-income countries, which may be a factor in the development of telemedicine [16]. Since then, more health professionals are using or ready to use telemedicine to support and integrate care processes [17]. This includes; helping patients learn how to better manage themselves through the effective exchange of health information between patients from home to healthcare professionals in clinical settings [18]. The WHO declared coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a pandemic on March 11, 2020, necessitating the need for prolonged social isolation [19]. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has also played a significant role in the expansion of telemedicine, which made it possible for patients to receive care from their homes, reducing the risk of transmission of the disease [20].

Ghana in its quest to make healthcare accessible has made tremendous progress in the implementation and use of telemedicine. According to a piloted study in the Ashanti region carried out by the Novartis Foundation in 2016, telehealth was successfully implemented and used in 10 selected communities with about 35000 people benefiting from the programme [21]. In addition, Vodafone Ghana also implemented a telehealth program called the Vodafone Healthline, which sought to empower Ghanaians on health issues by encouraging regenerative health among the populace [22]. BIMA, a Swedish company in 2015 also implemented similar telemedicine services in Ghana that aimed at making healthcare and health promotion activities accessible to the citizens [23]. Other early initiatives to improve access to basic healthcare in rural areas in the country have been explored using mobile health technology [24,25]. The benefits of telehealth cannot be overlooked especially in the peak of COVID-19 despite the challenges [26].

Patients' willingness to pay (WTP) for telemedicine services is an important factor to consider in addition to telemedicine's efficacy because WTP serves as a proxy for service demand and acceptance. WTP is also influenced by the consumers' income levels [27]. The issue of WTP is a crucial one in the innovative ICT platform. According to Minyihum et al., WTP is an effective research strategy that involves potential customers determining their preferences for proposed services and the value they are willing to pay [28]. The maximum amount of resources that buyers are willing to forego during a transaction in exchange for an object is referred to as the “WTP”. When a buyer's WTP is greater than the cost of the item sold, they would consider whether the trade is beneficial to themselves and then make the purchase [29]. In non-technical language, the maximum amount a person is willing to pay for goods or services rather than go without them is known as the WTP for a service. According to de Bekker‐Grob et al., WTP is increasingly being used to develop health care policy as a concept [30].

The contingent valuation method (CVM) can be used in a variety of ways to elicit a person's WTP, including an open-ended elicitation method [31,32] and a payment card method [33]. Additionally, it includes; a dichotomous choice approach, also known as a closed-ended method or referendum [34], and a choice experiment method [35]. Nevertheless, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) panel recommends the dichotomous choice method [[36], [37], [38], [39]] because the literature highlights a number of its advantages, including the fact that it requires little cognitive effort from respondents. According to Venkatachalam [40], open-ended elicitation and dichotomous methods are widely used by developed and developing countries. One of the strengths of the open-ended CVM is that it eliminates the need for an interviewer and any starting-point bias, making it easier and more convenient for participants to respond to WTP questions [41]. The open-ended elicitation method was used in this study. Study participants were required to state their maximum WTP amount for telemedicine services without being given any prior amount for the following reasons: (i) the open-ended method theoretically provides relatively unbiased WTP responses, in contrast to the dichotomous choice method, according to the literature, which demonstrates that it does not have a starting-point bias. (ii) Additionally, it avoids the potential for respondents to be misled and confused by split samples in the dichotomous choice approach [40,42,43]. (iii) Due to the questions' closed-ended nature, the open-ended approach helps to avoid the ex-ante restriction of patient responses and the cognitive bias of anchoring effects that are inherent in dichotomous choice approaches. (iv) The open-ended approach contributes to providing a specific valuation or welfare number for each survey respondent, which facilitates relatively simple subsequent analysis as merit [44]. The "willingness to pay" refers to the amount that must be deducted from the household's income. The contingent valuation method (CVM), which can also be used to inquire about consumers' willingness to pay for a new product, is used to collect the willingness data. Developing nations are increasingly utilizing CVM [45,46]. Using non-measurable economic benefits or costs is the most common method for estimating the monetary value of hypothetical goods that are not yet on the market [47].

A stated preference approach for measuring the use and passive use benefits of government policy is the contingent valuation method (CVM). Benefit estimates from the CVM and preference methods have been compared in several studies. Carson et al.'s [48] meta-analysis of more than one hundred studies looked at CVM and reported preference method showing similarity in results estimates across methods. The CVM's capacity to elicit economic values from individuals who do not directly experience the changes brought about by policy (passive use values) is one of its advantages. Passive use values include; respect for the integrity of the environment, generosity to others, and leaving a legacy for future generations.

Studies [[49], [50], [51]] have shown that hypothetical bias, or the tendency for hypothetical willingness to pay to overestimate real willingness to pay, is the CVM literature's most predominantly worrying result. When CVM respondents claim that they will pay for a good, but in reality, they will not, or they will pay less, in a similar purchase decision, this is known as hypothetical bias. The presence of passive use values and a lack of familiarity with paying for policies that provide passive use value are typically the causes of hypothetical bias. Nonetheless, theoretical predisposition has been found in various applications including private products for which no latent use values ought to exist [52]. A surprising amount of the CVM literature ignores hypothetical bias (Harrison, 2006).

Whitehead and Cherry assert that responses to CVM willingness-to-pay questions have no real consequences other than a tenuous link to the influence of government policy [53]. Hypothetical bias develops as a result of this. A desire to please the interviewer (e.g., yea saying) and an attempt to influence policy by signalling their support (e.g., strategic bias, warm glow) are two reasons for this behaviour [53]. Hypothetical bias causes willingness to pay estimates that are biased upward. According to Whitehead & Cherry, unless steps are taken to mitigate hypothetical bias, the willingness to pay estimates from the CVM that contain passive use values ought to be considered upper bounds of benefits in the context of cost-benefit analysis [53].

Understanding WTP is important for decision-making. This is because knowing how much people are willing to pay for telemedicine services will help in planning for sustainable financing, allocation of resources, and creation of a pricing plan for telemedicine services. Additionally, research into the factors that influence how much money patients' WTP is essential because this information will be useful in the development of interventions to further enhance WTP. The majority of the current published literature comprises findings related to cost-effectiveness analyses, which serve as a source of information for healthcare financing from the provider's perspective. These costs may include staffing, equipment, consumables, and other operational cost [54,55]. Few studies, however, have examined WTP from the patient's perspective, even though it is essential for the long-term viability of telemedicine interventions. This study aims to fill this knowledge gap by examining patients' willingness to pay for telemedicine services and the factors that influence how much money are patients willing to pay for telemedicine services amidst the fear of COVID-19.

The following term has been defined concerning the objectives of this study: Willingness to Pay (WTP) for Telemedicine Services: The maximum (non-zero) amount that patients are willing to pay for telemedicine services using the open-ended elicitation contingent valuation method. This study has been organised as follows: the introduction highlights the background of the study, the method section looks at the protocol used for the research work, the results and discussion interpret and discusses the outcomes from the study and finally, the conclusion looks at the main outcomes of the study.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

To determine patients’ willingness to pay for telemedicine services and related factors amid the COVID-19 pandemic, a cross-sectional survey was conducted among patients in six purposively selected healthcare facilities in Ghana.

2.2. Study settings

The six study facilities comprise a tertiary facility called Cape Coast Teaching Hospital (CCTH), three secondary health facilities, namely; Akuse Government Hospital, Suntreso Government Hospital, and Ejisu Government Hospital, and two health centres, namely; Assin Fosu Health Centre and Wenchi Health Centre.

2.3. Study population and eligibility criteria

The target respondents were patients attending hospitals in the six selected health facilities. Patients aged 18 years and above were included in the study. Excluded were patients below the age of 18 and patients who accessed the health facilities less than six months before the commencement of the study. Patients who refused to take part were not included.

2.4. Method for selecting a sample size

Based on an a priori power analysis, the minimum sample size for this investigation was determined [56,57]. Thus, we sampled a minimum of 194 respondents, as this would provide enough statistical power (0.80) to detect small correlation coefficients (0.20) [56], making room for a larger sample size, which would strengthen the robustness of our findings and increase the statistical power needed to detect smaller effects. Six hospitals, the Cape Coast Teaching Hospital, Akuse Government Hospital, Assin Fosu Health Centre, Wenchi Health Centre, Suntreso Government Hospital, and Ejisu Government Hospital were purposively selected for the study (Table 1). Respondents were patients receiving service from the outpatient department of these hospitals and were available and willing to participate in the study. Outpatients were selected using a systematic sampling method in each hospital. The day's outpatient records' serial numbers or outpatient record numbers, which are recorded in the outpatient register, were used during the visit. An interval of six (6) was determined by dividing the expected total sample size of 1164, by the sample size of 194, for each hospital. The first patient's number was picked at random from the day's list of outpatients. Subsequent outpatients were selected using the intervals that were obtained. The participants were selected in each hospital until a desired sample size was reached. A total sample of 1227 respondents was selected for the study. Table 1 shows the distribution of the number of respondents by health facility.

Table 1.

Distribution of respondents by health facility.

| Name of Health facility | Number of respondents | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Cape Coast Teaching Hospital | 350 | 28.52 |

| Akuse Government Hospital | 250 | 20.37 |

| Assin Fosu Health Centre | 98 | 7.99 |

| Wenchi Health Centre | 200 | 16.3 |

| Suntreso Government Hospital | 165 | 13.45 |

| Ejisu Government Hospital | 164 | 13.37 |

| Total | 1227 | 100 |

A priori power sample size calculation is denoted by

Where.

N = sample size

α (two-tailed) = 0.05 (Threshold probability for rejecting the null hypothesis. Type I error rate).

β = 0.20 (Probability of failing to reject the null hypothesis under the alternative hypothesis. Type II error rate).

R = 0.20 (The expected correlation coefficient).

The standard normal deviation for α = Zα = 1.9600.

The standard normal deviation for β = Zβ = 0.8416

2.5. Variables of the study

The dependent variable was how much money patients were willing to pay for telemedicine services. The factors such as socio-demographic variables (age, sex, marital status, employment status, and religion), socioeconomic variables (level of education, valid national health insurance scheme (NHIS), and WTP for telemedicine services), patient concerns concerning accessing the out-patient department (OPD) and the in-patient department (IPD)) during the COVID-19 out-break (afraid of visiting the hospital due to fear of contracting COVID-19, worried about managing my health during the pandemic, If I have to undergo any elective surgery, I am willing to delay it by more than six (6) months or until I receive the COVID-19 vaccine and the frequency of hospital visits during this COVID-19 period compared to the before-COVID-19 period) and patient/physician consultation using Telemedicine Technology were the independent variables.

2.6. Data collection procedure

The survey instruments were pre-tested at the Cape Coast Metropolitan Hospital, which is not one of the health facilities selected for the study. This hospital has similar characteristics to the six selected study hospitals. We changed a few questions after the pre-testing.

From October to November 2021, we collected data from participants using a pre-tested questionnaire administered by interviewers. A face-to-face interview technique was employed to solicit responses from the participants. Six trained field officers fluent in English and the local languages collect the data. We adapted the survey instrument from an earlier study [58]. The data collection instrument comprises seven questions on socio-demographic characteristics, four questions on patient concerns about accessing outpatient and inpatient services during the COVID-19 outbreak, and 12 questions on patient and physician consultation using telemedicine technology. Before determining patients’ WTP, we provided the respondents with a comprehensive description of the hypothetical telemedicine, including its advantages using telemedicine services as suggested by other studies [40,59].

We used an open-ended elicitation method in this study. Study participants were required to state their maximum WTP amount for telemedicine services without being given any prior amount. An average of 9 min was spent conducting each interview. In summary, the valuation methodology with a face-to-face interview of patients attending hospitals in the six selected health facilities yielded 1227 respondents. The questions used to elicit the patient WTP were in two-part:

-

(a)

Considering all the telemedicine services' effects and benefits, will you be willing to use and pay for telemedicine services for your healthcare? 1 = [ ] No; 2 = [ ] Yes

-

(b)

If yes in (a) above (i.e., are you willing to use telemedicine services for your healthcare), then how much will you be willing to pay per visit for the telemedicine services? ____.

Only respondents who said they were willing to use and pay for telemedicine services had to answer the question (b). Every day, the principal investigator double-checked the accuracy and consistency of the collected data by monitoring and supervising the entire process.

2.7. Data management

Before data were entered into an electronic data-capturing tool developed using EpiData 3.1, each questionnaire was checked for eligibility, completeness, and accuracy. To reduce data entry errors, in-build checks were included in the data screens. For purposes of quality control and easy recall, unique numbers were assigned to each completed questionnaire.

2.8. Data analysis

We applied the open-ended CVM in data collection. Descriptive statistics such as frequencies, proportions, means, and standard deviation was used to present the data. The probit model was used to estimate the average WTP. The factors associated with how much money patients were willing to pay were estimated using Tobit methods. To learn about the characteristics of the study population, we looked for outliers and chose an appropriate statistical method to examine the distribution of each variable. Shapiro-Wilk and Bartlett's tests were used to determine whether or not the dependent variable (how much money patients were willing to pay) was normal and assumed equal variance. The willingness to pay (i.e., the dummy variable, yes or no) and how much money the respondents are willing to pay were used as dependent variables. Using an open-ended question format, the CVM was used to estimate the telemedicine service's WTP. We estimated the average WTP and its associated factors by applying the single-bounded dichotomous format. Stata 15 was used to analyse the data, and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.9. Ethical consideration

The Cape Coast Teaching Hospital Ethical Review Committee granted us ethical approval (REF: CCTHERC/EC/2021/081). Before conducting the interviews, we also explained the purpose of the study to respondents and obtained their verbal informed consent. By removing any potential personal identifiers and employing a coding system, we ensured the participants' information remained private.

2.10. Model specification

Currently, the Tobit model is referred to as the "censored normal regression model." [60]. It assumes that many variables have a threshold value, known as a lower or upper limit, and assumes this limiting value for a sizeable number of respondents. The variable varies widely above the limit for the remaining sample respondents. The model's explanatory variables may have an impact on both the size of non-limit responses and the probability of limiting responses. By applying the Tobit model, we have classical regression for continuous variables and the needed probabilities for the zero observations, respectively. Considering the pattern of the model, this study is a good fit for Tobit analysis. The structural equation of the Tobit model censored from below, as Scott Long [61] describes it, can be expressed as in equation Eq (1)[ [61]]:

| (1) |

where the non-observable latent variable; Xi is the vector of the factor that influences willingness to pay.

In the logit model of single-bounded dichotomous format, the participants are given an initial bid value, which they may accept or reject. The dummy variable is the dependent variable in the logit model. The Logit model's goal is to estimate the mean WTP. The following is how the Logit model is expressed as described by Gujarati [62] in equation Eq (2)[ [62]]:

| (2) |

Where P(X) is the likelihood that a particular patient is willing to pay; β0 is a constant term; βi is the estimated regression coefficient or the Logit parameter; and Xi is the initial price; ϵi is the Logit regression's error term.

According to Hanemann, one of the primary goals of estimating an empirical WTP model using CVM survey responses is to determine the central value or mean of the WTP distribution [39]. Since Gujarati claims that the Probit and Logit models produce comparable results, the Logit model was utilized for the estimation due to its comparative computational simplicity [62]. However, the mean WTP is expressed as in equation Eq (3)[ [39]]:

| (3) |

Where: β1 = bid coefficient; βo = Constant term.

3. Results

3.1. Respondents’ background information

The characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 2. In all, 1227 respondents were involved in the study from six selected health facilities across the country. Male respondents were 44.25% (543), while females accounted for 55.75% (684). Patients range in age from 18 to 80 years old. The majority of 34.64% (425) of patients were in the age group 18–29 years, followed by the 30–39-year age group, which accounted for 32.68% (401). The lowest 8.64% (106) were in the 50–59-year age group. Out of the 1227 participants, 51.67% (634) had tertiary education, 30.07% (369) received secondary education, and 9.13% (112) received primary and no formal education, respectively. Half of the respondents, 50.04% (614) were married, while 38.14% (468) were single. Of the 1227 respondents, 88.59% (1087) had a valid national health insurance card, and only 11.41% (140) did not have a valid national health insurance card. On the employment status side, 53.3% (654) were employed, 24.12% (296) were unemployed, 15.81% (194) were students, and 6.76% (83) were retired. Christians made up 77.18% (947), Muslims made up 21.52% (264), and other religious denominations made up only 1.3% (16).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of patients attending hospitals in the six selected health facilities in Ghana.

| Characteristics | Frequency N=1227 |

Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age-group | ||

| 18–29 years | 425 | 34.64 |

| 30–39 years | 401 | 32.68 |

| 40–49 years | 168 | 13.69 |

| 50–59 years | 106 | 8.64 |

| 60 years and above | 127 | 10.35 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 543 | 44.25 |

| Female | 684 | 55.75 |

| Education level | ||

| No formal education | 112 | 9.13 |

| Primary | 112 | 9.13 |

| Secondary | 369 | 30.07 |

| Tertiary | 634 | 51.67 |

| Valid NHIS | ||

| Yes | 1087 | 88.59 |

| No | 140 | 11.41 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 468 | 38.14 |

| Married | 614 | 50.04 |

| Divorced/Separated | 74 | 6.03 |

| Cohabiting | 71 | 5.79 |

| Employment status | ||

| Student | 194 | 15.81 |

| Unemployed | 296 | 24.12 |

| Employed | 654 | 53.3 |

| Retired | 83 | 6.76 |

| Religion | ||

| Christians | 947 | 77.18 |

| Muslims | 264 | 21.52 |

| Others | 16 | 1.3 |

Data are presented as numbers and percentages.

N is the total number of participants.

3.2. Patient concerns about accessing outpatient and inpatient services during the COVI-19 outbreak

Out of the 1227 respondents, most (67.97%, or 834) indicated that they were afraid of visiting the hospital due to a fear of catching COVID-19, while 32.03% (393) were not. When asked if they were concerned about managing their health amid COVID-19, 62.27% (764) said yes and 37.73% (463) said no as shown in Table 3. Again, the majority (67.64%) (830) said they are willing to postpone any elective surgery for more than six months or until they receive the COVID-19 vaccine, whereas 32.36% (397) said they will not. The majority of 41.65% (511) said their frequency of hospital visits during the COVID-19 period has not changed compared to the pre-COVID-19 period, 37.73% (463) said it has decreased, and 20.62% (253) said it has increased as in Table 3.

Table 3.

Percentage distribution of patient concerns in accessing outpatient and inpatient services during the COVID-19 out-break and Patient/Physician consultation using Telemedicine Technology.

| Issues | Frequency N=1227 |

Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Afraid of visiting hospital due to fear of catching COVID-19 | ||

| Yes | 834 | 67.97 |

| No | 393 | 32.03 |

| Worried about managing my health amid the COVID-19 pandemic | ||

| Yes | 764 | 62.27 |

| No | 463 | 37.73 |

| If I have to undergo any elective surgery, I am willing to delay it by more than 6 months or until I receive the COVID-19 vaccine | ||

| Yes | 830 | 67.64 |

| No | 397 | 32.36 |

| Frequency of hospital visits during this COVID-19 period compared to the before-COVID-19 period | ||

| Increased | 253 | 20.62 |

| Decreased | 463 | 37.73 |

| No change | 511 | 41.65 |

| Accessed telemedicine services during the COVID-19 period or before the COVID-19 outbreak | ||

| Yes | 228 | 18.58 |

| No | 999 | 81.42 |

| Willingness to use telemedicine now | ||

| Yes | 903 | 73.6 |

| No | 324 | 26.4 |

| Willing to pay for Telemedicine services just as you pay for In-person consultation | ||

| Yes | 903 | 73.6 |

| No | 324 | 26.4 |

| Worried about Data Privacy, Confidentiality, and Security concerning the use of Telemedicine services | ||

| Yes | 799 | 65.12 |

| No | 130 | 10.59 |

| Don't care | 298 | 24.29 |

Data are presented as numbers and percentages.

N is the total number of participants.

Most (81.42% or 999) of the participants indicated that they had not accessed telemedicine services during the COVID-19 period or before the COVID-19 outbreak (Table 3). Only 18.58% (228) indicated accessing telemedicine services during the COVID-19 period or before the outbreak. The analysis further revealed that 73.6% (903) of respondents indicated their willingness to use telemedicine now, whereas 26.4% (324) said no. Out of the 1227 respondents, most 73.6% (903) said they were willing to pay for telemedicine services just as they would for in-person consultations, whereas 26.4% (324) indicated otherwise (Table 3). Regarding data privacy, confidentiality, and security concerning the use of telemedicine services, 65.12% (799) said they were worried about data privacy, confidentiality, and security using telemedicine technology, 10.59% (130) were not, and 24.29% (298) do not care about data privacy, confidentiality, or security (Table 3).

3.3. Patients’ willingness to consult with medical specialists using telemedicine

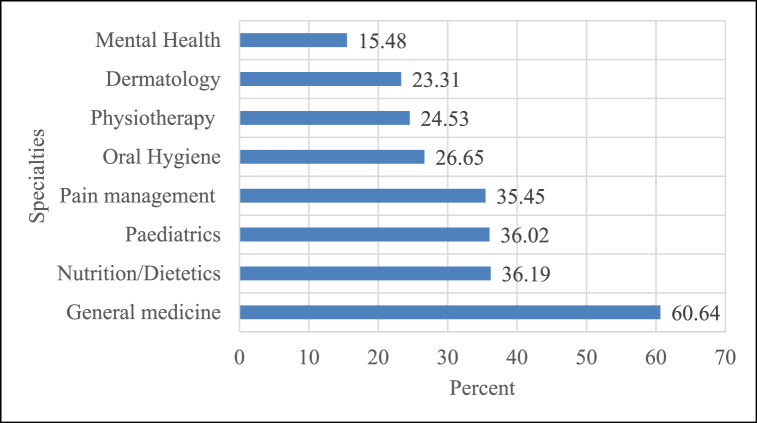

Concerning the use of telemedicine services, figure 1 shows several respondents indicated their readiness to use telemedicine services for the following healthcare options: general medicine (60.64%), paediatric consultations (36.02%), nutrition/dietetics consultations (36.19%), pain management consultations (35.45%), mental health consultations (15.48%), dermatology consultations (23.31%), physiotherapy consultations (24.53%), and oral hygiene consultations (26.65%).

Figure 1.

Percentage distribution of willingness to use telemedicine for consultations across different specialties.

3.4. Willingness to pay analysis

Out of the 1227 participants, 903 (73.6%) responded to their readiness to use and pay for telemedicine, services while 324 (26.4%) responded no as shown in Table 4. The estimation of the mean WTP was based on the 903 participants who were willing to use and pay for telemedicine services. Out of the total sample of 903 respondents, 3.54% (32) said they were willing to pay nothing (zero amount), while 96.46 percent (871) offered how much money they were willing to pay. Patients' primary reasons for refusing the service include their inability to pay for it and their lack of trust in the services. The stated average WTP for telemedicine services per visit was GHȻ55.55 (US$6.17)1, and the standard deviation of GHȻ52.61 with a 95% confidence interval of GHȻ52.12 to GHȻ58.99. Table 4 shows the summarized amount of money the respondents were willing to pay.

Table 4.

Summary of how much money patients were willing to pay and total revenue WTP in Ghana Cedis (GH').

| The class interval for Amount WTP Ghana Cedis (GH') | Number Patients | Percent | Total Amount WTP Ghana Cedis (GH') | Average WTP Ghana Cedis (GH') (SD) | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 51 | 610 | 67.55 | 17,663.00 | 28.96 (16.93) | [27.61–30.30] |

| 51 - 100 | 219 | 24.25 | 18,560.00 | 84.75 (15.03) | [82.75–86.75] |

| 101 - 150 | 31 | 3.43 | 4400.00 | 141.94 (13.27) | [137.07–146.80] |

| 151 - 200 | 35 | 3.88 | 6740.00 | 192.57 (14.62) | [187.55–197.59] |

| Above 200 | 8 | 0.89 | 2800.00 | 350.00 (92.58) | [272.60–427.40] |

| Overall | 903 | 100 | 50,163.00 | 55.55 (52.61) | [52.12–58.99] |

Note: Total number of respondents willing to pay for telemedicine services is 903. SD – Standard deviation.

1BoG. (2023). Bank of Ghana Daily Interbank FX Rates. [Online] Available at: https://www.bog.gov.gh/treasury-and-the-markets/daily-interbank-fx-rates/Accessed 10-01-2023.

3.5. Estimation of the mean WTP

The coefficients of the regression on the initial bid value is as shown in Table 5, and the willingness to pay for the single-bounded dichotomous format is as follows:

Where: β1 = bid coefficient = 0.0170 as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

The output from the Logit model to compute the average amount of WTP from Telemedicine services.

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | z | p-value | [95% Confidence Interval] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BID | 0.0170 | 0.0068 | 2.5 | 0.012* | [0.0037–0.0303] |

| Constant | 1.6967 | 0.1992 | 8.52 | <0.001** | [1.3064–2.0870] |

Statistically significant at *p-value<0.05; **p-value<0.001.

1BoG. (2023). Bank of Ghana Daily Interbank FX Rates. [Online] Available at: https://www.bog.gov.gh/treasury-and-the-markets/daily-interbank-fx-rates/Accessed 10-01-2023.

βo = Constant term = 1.6967 as shown in Table 5

From the model estimation, the mean willingness to pay was GHȻ109.71 (US$12.19) 1 per visit. However, the stated mean WTP for telemedicine service was GHȻ55.55 (US$6.17) 1, which is lower than the Logit model estimates' mean value of GHȻ109.71 (US$12.19)1 per visit. The consequence of this outcome shows that willingness to pay should not exceed GHȻ109.71 (US$12.19) 1 per visit for the proposed telemedicine services. The higher mean WTP realised from the logit model is supported by studies that confirm that the use of open-ended CVM produces a high value compared to other CVMs (like the single or double dichotomous CVM) [53,63,64].

3.6. Factors affecting how much money patients were willing to pay for telemedicine services

According to the unadjusted Tobit model, demographic variables such as age and gender were statistically significantly related to the amount of money patients were willing to pay to use telemedicine services (Table 6). COVID-19-related variables, such as being afraid of visiting a hospital due to fear of contracting COVID-19, being concerned about managing health amid the COVID-19 pandemic, deferring elective surgery for more than 6 months or after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine, and having used telemedicine services during or before the COVID-19 out-break, were statistically significant. On the issue of telemedicine usage for healthcare options, variables such as willingness to use telemedicine now; willingness to pay (WTP) for telemedicine services just as you pay for in-person consultations, willingness to use telemedicine for paediatric consultations, and willingness to use telemedicine for nutrition/dietetic consultations were also statistically significantly associated with the amount of money patients were willing to pay for telemedicine services (Table 6).

Table 6.

Unadjusted Maximum Likelihood estimates of the Tobit model.

| Covariates | Est. Coef. [95% CI] | Robust SE | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 7.72 [4.80-10.64] | 1.49 | <0.0001** |

| Gender | −8.08 [-15.16–0.99] | 3.61 | 0.0254* |

| Education level | 3.41 [-0.09-6.92] | 1.79 | 0.0564 |

| Valid NHIS | 0.96 [-8.85-10.78] | 5.00 | 0.8476 |

| Marital status | 3.41 [-0.82-7.64] | 2.16 | 0.1141 |

| Employment status | −0.25 [-3.52-3.01] | 1.66 | 0.8786 |

| Religion | −2.30 [-10.46-5.86] | 4.16 | 0.5807 |

| Afraid of visiting hospital due to fear of catching COVID-19 | 8.43 [5.83-11.03] | 1.33 | <0.0001** |

| Worried about managing my health amid the COVID-19 pandemic | 6.35 [3.56-9.13] | 1.42 | <0.0001** |

| If I have to undergo any elective surgery, I am willing to delay it by more than 6 months or until I receive the COVID-19 vaccine | 6.56 [3.83-9.28] | 1.39 | <0.0001** |

| Frequency of hospital visits during this COVID-19 period compared to before-COVID-19 period | 4.03 [-0.09-8.15] | 2.10 | 0.055 |

| Accessed telemedicine services during the COVID-19 period or before the COVID-19 outbreak | −9.73 [-17.64–1.83] | 4.03 | 0.0159* |

| Willingness to use telemedicine now | 9.64 [3.21-16.07] | 3.28 | 0.0033* |

| Willing to pay for Telemedicine services just as you pay for In-person consultation | 35.99 [26.84-45.14] | 4.66 | <0.0001** |

| Willing to use telemedicine for General medicine consultations | 5.00 [-1.94-11.93] | 3.53 | 0.1576 |

| Willing to use telemedicine for Paediatrics consultations | 21.77 [14.35-29.18] | 3.78 | <0.0001** |

| Willing to use telemedicine for Nutrition/Dietetics consultations | 11.73 [4.10-19.35] | 3.88 | 0.0026* |

| Willing to use telemedicine for Pain management consultations | 3.93 [-3.27-11.13] | 3.67 | 0.2838 |

| Willing to use telemedicine for Mental Health consultations | −2.82 [-11.88-6.23] | 4.61 | 0.5407 |

| Willing to use telemedicine for Dermatology consultations | −1.76 [-10.11-6.58] | 4.25 | 0.6784 |

| Willing to use telemedicine for Physiotherapy consultations | 1.13 [-6.73-8.99] | 4.01 | 0.7777 |

| Willing to use telemedicine for Oral Hygiene consultations | 0.21 [-7.38-7.80] | 3.87 | 0.9570 |

Statistically significant at *p-value<0.05; **p-value<0.001.

Est. Coef. – Estimated Coefficient; CI – Confidence Interval; SE – Standard Error.

4. Discussions

Our study seeks to determine patients’ willingness to pay for telemedicine services and associated factors amidst the fear of COVID-19 in Ghana. The outcome of the study was summarized using the proportion of patients who were willing to pay for telemedicine services, as well as the amount they were willing to pay. A total of 1227 respondents were involved in the study. Most of the respondents indicated that they were afraid of visiting the hospital due to their fear of catching COVID-19. Apart from that, the majority were also worried about managing their health amid COVID-19. These findings were in agreement with Deloitte [58]. Furthermore, the majority indicated that, if they have to undergo any elective surgery, they are willing to delay it by more than 6 months or until they receive the COVID-19 vaccine. A study conducted by Deloitte in 2020 supports our findings [58]. As a result, hospitals may see many elective procedures delayed if there are any possible subsequent COVID-19 waves, leading to an increase in elective procedures. The majority 41.7% said their frequency of hospital visits during this COVID-19 period compared to the before-COVID-19 period has not changed, 37.7% said it has decreased, and 20.6% said it has increased.

Additionally, patients indicated preferences for telemedicine platforms. The majority of respondents (60.6%), would rather switch from in-person consultations to telemedicine consultations for general medicine. Additionally, a proportion of patients ranging from 23% to 36% also indicated replacing in-person consultations with telemedicine consultations in the areas of paediatric care, pain management, oral hygiene, physiotherapy, and dermatology consultations. Given the willingness to use telemedicine services for consultations across various specialties, hospitals need to consider expanding telemedicine service platforms and digitally upgrading their medical staff to be ready for the shift from in-person consultations to telemedicine services. Security, confidentiality, and data privacy were also some of the primary concerns of respondents, with over 60% of the respondents’ exhibiting such views. This suggests that care providers must establish adequate data protection mechanisms to safeguard any online or digital platforms that support telemedicine services.

Concerning the percentage of patients willing to pay for telemedicine services, 73.6% were willing to pay for the telemedicine services. This means that the majority of the patients who participated in the study were willing to pay for telemedicine services as part of their healthcare. Our findings are in agreement with studies conducted in countries like Vietnam [65]; the United Kingdom [66]; and Belgium [67], where the majority of respondents were willing to use and pay for telemedicine technology. Increasing interest in telemedicine is likely to lead to long-term trends like home diagnostic sample collection and home drug delivery, which will force established companies to build skills for non-traditional forms and channels of care delivery.

According to the findings of this study, the mean WTP was estimated to be GHȻ109.71 (US$12.19) 1 per visit based on econometric analysis. The average WTP for telemedicine services as reported by our study is lower than other studies conducted by Fawsitt and co (US$30.96) [32], and Ngan and co (US$59.99) [65]. Patients' willingness to pay will have to be taken into consideration when setting prices for services. This could be due to the diverse socioeconomic backgrounds of the patients who participated in the study. Apart from that, Ghana's minimum wage is quite low (GHȻ14.88) (US$1.65)1 [68] compared to the amount patients were willing to pay for telemedicine services.

In our study, demographic characteristics such as age and gender were found to be statistically significantly associated with WTP for telemedicine services. Our findings agree with studies [66,[69], [70], [71]] that age and gender are statistically significantly correlated with WTP for telemedicine services. However, other sociodemographic factors such as education level, a valid NHIS card, marital status, employment status, and religion were not associated with the amount of money that patients were willing to pay for telemedicine services. The study also revealed a significant relationship between COVID-19-related variables (i.e. being afraid of visiting a hospital due to fear of contracting COVID-19, being concerned about managing health amid the COVID-19 pandemic, and deferring elective surgery for more than 6 months or after receiving the.

1BoG. (2023). Bank of Ghana Daily Interbank FX Rates. [Online] Available at: https://www.bog.gov.gh/treasury-and-the-markets/daily-interbank-fx-rates/Accessed 10-01-2023.

COVID-19 vaccine) and how much money patients were willing to pay for telemedicine services. These variables have an increasing effect on how much money the patients were willing to pay for the telemedicine services. This is an indication of higher demand on the use of telemedicine services. Players in the healthcare industry would be able to position themselves to meet the growing demand for remote healthcare since this is in line with the UN SDG 3 of access to health and wellbeing [72]. The study has also revealed that the patients were willing to use telemedicine now. Other determinants which significantly had a positive influence on how much money the patients were willing to pay were ‘willingness to use telemedicine now’; ‘willingness to pay for telemedicine services just as they pay for in-person consultations’, ‘willingness to use telemedicine for paediatric consultations’, and ‘willingness to use telemedicine for nutrition/dietetic consultations. The growth in the number of options available for accessing health care by patients has re-echoed the need for rapid development of telemedicine services. This will further lead to promoting universal health coverage for all in low-and-middle-income countries.

5. Study Implications

Given the willingness to use telemedicine services for consultations across various medical specialties, hospitals should consider expanding telemedicine service platforms. This expansion should factor in the upgrading of skills of medical personnel to be ready for the provision of telemedicine services. Long-term trends like the home collection of diagnostic samples and the home delivery of pharmaceuticals may be sparked by an increased interest in telemedicine, requiring incumbent players to develop capabilities for non-traditional care delivery methods. Patient's willingness to pay for telemedicine services should be considered when setting prices, as well as their concerns about privacy, confidentiality, and data security.

6. Study strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is the use of open-ended CVM which eliminates the need for an interviewer and any starting-point bias, making it easier and more convenient for participants to respond to WTP questions. The study's primary limitation is using convenience sampling among healthcare facilities. As a result, it was impossible to attribute the findings to a larger population. A larger sample of healthcare facilities would have been more beneficial and generalizable. Another limitation was the high estimated WTP from the model. Other models can be explored in determining WTP for telemedicine services within the Ghanaian context. Despite this limitation, to our knowledge, there are no similar studies on patients' willingness to pay for telemedicine services in Ghana. This study is to help fill that gap.

7. Conclusion and recommendation

This study showed that the majority of the study participants are willing to use and pay for telemedicine services. The estimated willing to pay was a GHC109.71 ($12.19). Age and gender were the main demographic variables associated with how much money patients were willing to pay for telemedicine services. Other determinants were fear of catching covid-19, worried about managing health in the midst of covid-19, and delay in elective surgery. With an increased consumer preference for alternative non-traditional care delivery systems, healthcare providers must position themselves to provide remote care to patients in the safety and comfort of their homes. This will further promote the UN sustainable development goal 3, by ensuring access to quality healthcare for all without geographical limitations. We expect healthcare management to become significantly more integrated in the future, with players joining forces to provide patients with the necessary care they need. This study has paved the way for setting an average WTP from the patients’ perspective. Players in the healthcare industry can make use of this research in determining how much to charge consumers for telemedicine services, taking into consideration the low average wage per month of GHC 900 ($82.91) in the country. Currently, there is scanty or limited information on how much money patients are willing to pay using telemedicine services in Ghana. We recommend that further studies should be conducted with a larger number of health facilities on WTP.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Author contribution statement

Godwin Adzakpah & Nathan Kumasenu Mensah: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Richard Okyere Boadu: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Jonathan Kissi; Michael Dogbe; Michael Wadere; Dela Senyah; Mavis Agyarkoaa; Lawrencia Mensah; Amanda Appiah-Acheampong: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

List of abbreviation

- WTP

– Willingness to pay

- GH'

– Ghana Cedis

- CVM

– Contingent Valuation Method

- COVID-19

– Coronavirus disease 2019

References

- 1.Voorhoeve A., Ottersen T., Norheim O.F. Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage: a précis. Health Econ. Pol. Law. 2016;11(1):71–77. doi: 10.1017/S1744133114000541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grépin K.A., Irwin B.R., Sas Trakinsky B. On the measurement of financial protection: an assessment of the usefulness of the catastrophic health expenditure indicator to monitor progress towards universal health coverage. Health Systems & Reform. 2020;6(1) doi: 10.1080/23288604.2020.1744988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2021. Tracking Universal Health Coverage: 2021 Global Monitoring Report. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Umeh C.A., Feeley F.G. Inequitable access to health care by the poor in community-based health insurance programs: a review of studies from low-and middle-income countries. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2017;5(2):299–314. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leive A., Xu K. Coping with out-of-pocket health payments: empirical evidence from 15 African countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 2008;86(11):849–856C. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.049403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Misra S., et al. Assessing the magnitude, distribution and determinants of catastrophic health expenditure in urban Lucknow, North India. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health. 2015;3(1):10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panda P., et al. In: What Factors Affect Take up of Voluntary and Community Based Health Insurance Programmes in Low-And Middle-Income Countries. Panda P., Dror I., Koehlmoos T., Hossain S., John D., Khan J., Dror D., editors. 2013. What factors affect take up of voluntary and community-based health insurance programmes in low-and middle-income countries? Protocol. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domapielle M.K. Adopting localised health financing models for universal health coverage in Low and middle-income countries: lessons from the National Health lnsurance Scheme in Ghana. Heliyon. 2021;7(6) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schieber G., et al. 2012. Health Financing in Ghana. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarkodie A.O. Effect of the National Health Insurance Scheme on healthcare utilization and out-of-pocket payment: evidence from GLSS 7. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 2021;8(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akweongo P., et al. Insured clients out-of-pocket payments for health care under the national health insurance scheme in Ghana. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021;21(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06401-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sataru F., Twumasi-Ankrah K., Seddoh A. An analysis of catastrophic out-of-pocket health expenditures in Ghana. Frontiers in Health Services. 2022;2:1. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2022.706216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutledge C., et al. Telehealth and eHealth in nurse practitioner training: current perspectives. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2017;8:399–409. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S116071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 1998. A Health Telematics Policy in Support of WHO'S Health-For-All Strategy for Global Development: Report of the WHO Group Consultation on Health Telematics 11-16 December. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penedo F.J., et al. The increasing value of eHealth in the delivery of patient-centred cancer care. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(5):e240–e251. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30021-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2006. Neonatal and Perinatal Mortality: Country, Regional and Global Estimates. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mensah N.K., et al. Health professional's readiness and factors associated with telemedicine implementation and use in selected health facilities in Ghana. Heliyon. 2023;9(3) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wootton R. Twenty years of telemedicine in chronic disease management–an evidence synthesis. J. Telemed. Telecare. 2012;18(4):211–220. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.120219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kissler S.M., et al. Projecting the transmission dynamics through the postpandemic period. Science. 2020;368(6493):860–868. doi: 10.1126/science.abb5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gajarawala S.N., Pelkowski J.N. Telehealth benefits and barriers. J. Nurse Pract. 2021;17(2):218–221. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novartis Foundation . 2023. Ghana Telemedicine.https://www.novartisfoundation.org/past-programs/digital-health/ghana-telemedicine (Online) Available at: 04-05-2023. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vodafone Healthline . 2023. Healthline. Ghana Telemedicine.https://vodafone.com.gh/explore-vodafone/healthline/ (Online) Available at: 04-05-2023. [Google Scholar]

- 23.BIMA . 2023. BIMA Ghana. – Protecting the Future of Every Family (Online)https://bima.com.gh/ Available at: 04-05-2023. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Awoonor-Williams J.K., et al. 2010. The Mobile Technology for Community Health (MoTeCH) Initiative: an M-Health System Pilot in a Rural District of Northern Ghana (Working Draft) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rothstein J.D., et al. Qualitative assessment of the feasibility, usability, and acceptability of a mobile client data app for community-based maternal, neonatal, and child care in rural Ghana. Int. J. Telemed. Appl. 2016:2515420. doi: 10.1155/2016/2515420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lockhart A., et al. Making space for drones: the contested reregulation of airspace in Tanzania and Rwanda. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2021;46(4):850–865. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sackey F.G., Amponsah P.N. Willingness to accept capitation payment system under the Ghana National Health Insurance Policy: do income levels matter? Health Economics Review. 2017;7(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13561-017-0175-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minyihun A., Gebregziabher M.G., Gelaw Y.A. Willingness to pay for community-based health insurance and associated factors among rural households of Bugna District, Northeast Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes. 2019;12(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4091-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plassmann H., O'doherty J., Rangel A. Orbitofrontal cortex encodes willingness to pay in everyday economic transactions. J. Neurosci. 2007;27(37):9984–9988. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2131-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Bekker‐Grob E.W., Ryan M., Gerard K. Discrete choice experiments in health economics: a review of the literature. Health Econ. 2012;21(2):145–172. doi: 10.1002/hec.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adedokun A., Idris O., Odujoko T. Patients' willingness to utilize a SMS-based appointment scheduling system at a family practice unit in a developing country. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2016;17(2):149–156. doi: 10.1017/S1463423615000213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fawsitt C.G., et al. Surgical site infection after caesarean section? There is an app for that: results from a feasibility study on costs and benefits. Ir. Med. J. 2017;110(9) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Afroz R., Akhtar R., Farhana P. Willingness to pay for crop insurance to adapt flood risk by Malaysian farmers: an empirical investigation of Kedah. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues. 2017;7(4):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gebremariam G.G., Edriss A.K. Valuation of soil conservation practices in Adwa Woreda, Ethiopia: a contingent valuation study. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2012;3(13):97–107. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Löschel A., Sturm B., Vogt C. The demand for climate protection—empirical evidence from Germany. Econ. Lett. 2013;118(3):415–418. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Champ P.A., Boyle K.J., Brown T.C. Springer; Dordrecht: 2017. The economics of Non-market Goods and Resources. A Primer on Nonmarket Valuation. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carson R.T., Flores N.E., Meade N.F. Contingent valuation: controversies and evidence. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2001;19(2):173–210. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanemann M., Kanninen B. Valuing Environmental Preferences: Theory and Practice of the Contingent Valuation Method in the US, EU, and Developing Countries. Oxford University Press on Demand; 2001. 11 the statistical analysis of discrete-response CV data 147. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanemann W.M. Willingness to pay and willingness to accept: how much can they differ? Am. Econ. Rev. 1991;81(3):635–647. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oerlemans L.A., Chan K.-Y., Volschenk J. Willingness to pay for green electricity: a review of the contingent valuation literature and its sources of error. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016;66:875–885. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Venkatachalam L. The contingent valuation method: a review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2004;24(1):89–124. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diafas I. Georg-August-University Göttingen; Göttingen, Germany: 2014. Estimating the Economic Value of Forest Ecosystem Services Using Stated Preference Methods: the Case of Kakamega Forest. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Devicienti F.S.M., Irina K., Stefano P. 2004. Willingness to Pay for Water and Energy: an Introductory Guide to Contingent Valuation and Coping Cost Techniques. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Freeman A.M., III, Herriges J.A., Kling C.L. Routledge; 2014. The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values: Theory and Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alberini A., Cooper J. vol. 146. Food & Agriculture Org; 2000. (Applications of the Contingent Valuation Method in Developing Countries: A Survey). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Breidert C., Hahsler M., Reutterer T. A review of methods for measuring willingness-to-pay. Innovat. Market. 2006;2(4) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Y.-T., et al. Study of patients' willingness to pay for a cure of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2016;13(3):273. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13030273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carson R.T., et al. Referendum design and contingent valuation: the NOAA panel's no-vote recommendation. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1998;80(2):335–338. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cummings R.G., Harrison G.W., Rutström E.E. Homegrown values and hypothetical surveys: is the dichotomous choice approach incentive-compatible? Am. Econ. Rev. 1995;85(1):260–266. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cummings R.G., et al. Are hypothetical referenda incentive compatible? J. Polit. Econ. 1997;105(3):609–621. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blumenschein K., et al. Hypothetical versus real payments in Vickrey auctions. Econ. Lett. 1997;56(2):177–180. [Google Scholar]

- 52.List J.A., Gallet C.A. What experimental protocol influence disparities between actual and hypothetical stated values? Environ. Resour. Econ. 2001;20:241–254. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whitehead J.C., Cherry T.L. Willingness to pay for a green energy program: a comparison of ex-ante and ex-post hypothetical bias mitigation approaches. Resour. Energy Econ. 2007;29(4):247–261. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buvik A., et al. Cost-effectiveness of telemedicine in remote orthopedic consultations: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019;21(2) doi: 10.2196/11330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dalaba M.A., et al. Cost-effectiveness of clinical decision support system in improving maternal health care in Ghana. PLoS One. 2015;10(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bujang M.A., Baharum N. Sample size guideline for correlation analysis. World. 2016;3(1):37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hulley S.B., et al. Designing Clinical Research: an Epidemiologic Approach. 2001. Designing clinical research: an epidemiologic approach. 336-336. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Deloitte Changing consumer preferences towards health care services: the impact of COVID-19. 2020. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/in/Documents/life-sciences-health-care/in-lshc-Deloitte_HealthcareConsumerSurvey-new-noexp.pdf [Online] Available at: 10-10-2022.

- 59.Champ P.A., et al. vol. 3. Springer; 2003. (A Primer on Nonmarket Valuation). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Greene W.H. Pearson Education India; 2003. Econometric Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scott Long J. Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Advanced quantitative techniques in the social sciences. 1997;7 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gujarati D.N. SAGE Publications; 2021. Essentials of Econometrics. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brown T.C., et al. Which response format reveals the truth about donations to a public good? Land Econ. 1996:152–166. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aadland D., Caplan A.J. Willingness to pay for curbside recycling with detection and mitigation of hypothetical bias. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2003;85(2):492–502. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ngan T.T., et al. Willingness to use and pay for smoking cessation service via text-messaging among Vietnamese adult smokers. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2019;104:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2019.05.014. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Somers C., et al. Valuing mobile health: an open-ended contingent valuation survey of a national digital health program. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2019;7(1) doi: 10.2196/mhealth.9990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Scherrenberg M., Falter M., Dendale P. Patient experiences and willingness-to-pay for cardiac telerehabilitation during the first surge of the COVID-19 pandemic: single-centre experience. Acta Cardiol. 2021;76(2):151–157. doi: 10.1080/00015385.2020.1846920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yire I. National daily minimum wage for 2023 increased by 10 percent, now GHȻ14.88. Ghana News Agency. 2022 https://gna.org.gh/2022/11/national-daily-minimum-wage-for-2023-increased-by-10-per-cent-now-gh%C2%A214-88 [Online] Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kaga S., Suzuki T., Ogasawara K. Willingness to pay for elderly telecare service using the internet and digital terrestrial broadcasting. Interj med res. 2017;6(2) doi: 10.2196/ijmr.7461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shariful Islam S.M., et al. Mobile phone use and willingness to pay for SMS for diabetes in Bangladesh. J pub health. 2016;38(1):163–169. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Park H., et al. Service design attributes affecting diabetic patient preferences of telemedicine in South Korea. TELEMEDICINE and e-HEALTH. 2011;17(6):442–451. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2010.0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.UN Sustainable Development Goals - goal 3: ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. 2023. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/ (Online) Available at:

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.