Abstract

This survey study examines career choices of internal medicine residents from 2019 to 2021 and compares them with findings from a decade earlier.

Shortages of primary care clinicians are projected by numerous groups; the Association of American Medical Colleges projects a shortage of up to 48 000 primary care physicians by 2032.1 As internal medicine (IM) residents account for 24% of active US residents, career choices of IM residents will have significant implications for the future physician workforce.2 West et al3,4 reported on the career plans of graduating IM residents completing the Internal Medicine In-Training Examination (IM-ITE) in 2004 and found only 25% planned to enter general internal medicine (GIM); their subsequent 2012 analysis showed this proportion decreased further to 19.9%.4 We used national data from the 2019 to 2021 IM-ITE to evaluate career choice plans among IM residents to see if this trend has persisted despite programmatic and educational initiatives to address the shortage of primary care clinicians.5

Methods

A deidentified limited data set from the 2019 to 2021 IM-ITE surveys was provided by the American College of Physicians. The primary sample included categorical and primary care track IM residents who participated in the voluntary surveys. Residents from preliminary, medicine-pediatrics, or other program types, respondents who did not designate career choice, and respondents who declined the use of their data for research were excluded. This survey study was deemed not to be human participant research by the Northwell Institutional Review Board and thus was deemed exempt from review and informed consent.

Survey data were analyzed descriptively October 2022, using Excel, version 2208 (Microsoft). Stata, version 17 (StataCorp), was used to perform univariable and multivariable analysis of the odds of career plan for GIM by program type, sex, calendar year, and medical school location. We compared the choices of postgraduate year 3 (PGY3) residents from 2019 to 2021 with the 2012 analysis by West et al4 to describe changes in career plans over time.

Results

A total of 61 991 residents met inclusion criteria (26 751 females [43.2%] and 35 197 males [56.8%]), of whom 58 028 (93.6%) were in categorical programs and 3963 (6.4%) were in primary care programs. From 2019 to 2021, 5832 (9.4%) residents planned on a career in GIM, 9370 (15.1%) in hospital medicine (HM), and 42 102 (67.9%) in a subspecialty (Table).

Table. Demographic Characteristics and Career Plans of Internal Medicine Residents in 2019, 2020, and 2021.

| Variable | Residents, No. (%)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Total | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 8672 (42.7) | 9003 (42.8) | 9076 (43.9) | 26 751 (43.2) |

| Male | 11 613 (57.2) | 11 999 (57.1) | 11 585 (56.0) | 35 197 (56.8) |

| Medical school | ||||

| USMG | 12 381 (61.0) | 12 956 (61.6) | 13 453 (65.0) | 38 790 (62.5) |

| IMG | 7904 (38.9) | 8063 (38.3) | 7233 (34.9) | 23 200 (37.4) |

| Program type | ||||

| Categorical | 18 856 (92.9) | 19 711 (93.7) | 19 461 (94.0) | 58 028 (93.6) |

| Primary care | 1430 (7.0) | 1308 (6.2) | 1225 (5.9) | 3963 (6.4) |

| Year | ||||

| PGY1 | 6702 (33.0) | 6992 (33.2) | 6857 (33.1) | 20 551 (33.1) |

| PGY2 | 7147 (35.2) | 7372 (35.1) | 7297 (35.2) | 21 816 (35.1) |

| PGY3 | 6437 (31.7) | 6655 (31.6) | 6532 (31.5) | 19 624 (31.6) |

| Career plan | ||||

| General internal medicine | 1960 (9.6) | 1878 (8.9) | 1994 (9.6) | 5832 (9.4) |

| Hospital medicine | 3067 (15.1) | 3177 (15.1) | 3126 (15.1) | 9370 (15.1) |

| Subspecialties | 13 702 (67.5) | 14 360 (68.3) | 14 040 (67.8) | 42 102 (67.9) |

| Cardiology | 3188 (15.7) | 3351 (15.9) | 3287 (15.8) | 9826 (15.8) |

| Endocrinology | 644 (3.1) | 647 (3.0) | 650 (3.1) | 1941 (3.1) |

| Gastroenterology | 1918 (9.4) | 2030 (9.6) | 2017 (9.7) | 5965 (9.6) |

| Geriatrics | 191 (0.9) | 185 (0.8) | 196 (0.9) | 572 (0.9) |

| Hematology/oncology | 1756 (8.6) | 1841 (8.7) | 1771 (8.5) | 5368 (8.6) |

| Infectious diseases | 685 (3.3) | 690 (3.2) | 661 (3.1) | 2036 (3.2) |

| Nephrology | 427 (2.1) | 555 (2.6) | 572 (2.7) | 1554 (2.5) |

| Other subspecialtyb | 436 (2.1) | 508 (2.4) | 444 (2.1) | 1388 (2.2) |

| Pulmonology/critical care | 2030 (10.0) | 2164 (10.2) | 2019 (9.7) | 6213 (10.0) |

| Rheumatology | 638 (3.1) | 650 (3.0) | 697 (3.3) | 1985 (3.2) |

| Undecided subspecialty | 1789 (8.8) | 1739 (8.2) | 1726 (8.3) | 5254 (8.4) |

| Other (not IM)c | 168 (0.8) | 160 (0.7) | 159 (0.7) | 487 (0.7) |

| Undecided career plan | 1389 (6.8) | 1444 (6.8) | 1367 (6.6) | 4200 (6.7) |

Abbreviations: IM, internal medicine; IMG, international medical graduate; PGY, postgraduate year; USMG, US medical graduate.

Percentages may not equal 100 due to rounding.

Subspecialties included in this were not defined.

Other (not IM) includes residents who planned to pursue a career in another subspecialty (eg, surgery, pathology, consulting or nonclinical fields).

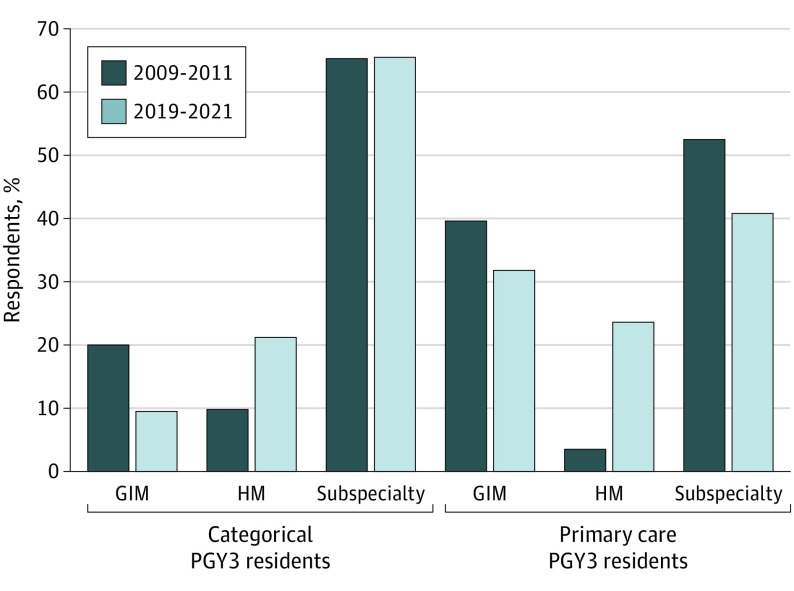

Among PGY3 residents in categorical programs, 9.5% chose GIM careers, 21.2% chose HM, and 65.5% chose a subspecialty. In primary care programs, 31.8% of PGY3 residents chose GIM careers, 23.6% chose HM, and 40.8% chose a subspecialty (Figure).

Figure. Career Plans for Categorical and Primary Care Postgraduate Year 3 (PGY3) Residents From 2009 to 2011 vs 2019 to 2021.

GIM indicates general internal medicine; HM, hospital medicine.

Among categorical PGY3 residents from 2009 to 2011 and 2019 to 2021, there was a decrease in GIM career plans of 10.4% and an increase in HM career plans by 11.4%, with minimal change in subspecialty career choice. Among primary care residents during the 10-year span, there was a 7.8% decrease in GIM career choices, a 20.1% increase in HM career choices, and an 11.7% decrease in residents desiring a subspecialty career (Figure).

In the fully adjusted model, primary care training program was associated with higher odds of selecting a GIM career (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 4.22; 95% CI, 3.71-4.76). Female sex (AOR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.58-0.69) and graduation from an international medical school (AOR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.77-0.93) were associated with lower odds of selecting a GIM career.

Discussion

Compared with 10 years prior, the percentage of graduating IM residents planning a career in GIM as of 2019 to 2021 has decreased by almost half, while HM has gained popularity. Reasons for this could be workload, high stress, work-life balance, and documentation pressures.6 Limitations of the study include selection bias due to cost of administration of the IM-ITE for programs and potential incongruency between survey responses and ultimate career choice. The IM-ITE data, along with the projected shortages in primary care providers, suggest that more needs to be done to encourage residents to pursue careers in GIM.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.American Association of Medical Colleges . The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2019 to 2034. June 2021. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/media/54681/download?attachment

- 2.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education . GME Resource Book 2020-2021. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/publicationsbooks/2021-2022_acgme__databook_document.pdf

- 3.West CP, Popkave C, Schultz HJ, Weinberger SE, Kolars JC. Changes in career decisions of internal medicine residents during training. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):774-779. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West CP, Dupras DM. General medicine vs subspecialty career plans among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2012;308(21):2241-2247. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.47535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coyle A, Helenius I, Cruz CM, et al. A decade of teaching and learning in internal medicine ambulatory education: a scoping review. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(2):132-142. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-18-00596.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linzer M, Poplau S, Babbott S, et al. Worklife and wellness in academic general internal medicine: results from a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):1004-1010. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3720-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Sharing Statement