Abstract

This cohort study examines trends in suicide rates for veterans with and without traumatic brain injury compared with the US adult population.

In 2020, the suicide rate among US veterans was 31.7 per 100 000, 57.3% greater than nonveterans, and suicide was the second leading cause of death for veterans younger than 45 years.1 Between 2000 and 2020, over 460 000 US service members were diagnosed with traumatic brain injuries (TBIs).2 Veterans serving after 9/11 have higher suicide rates compared to the US population, which is exacerbated by TBI exposure.3 This study examined trends in suicide rates for veterans with and without TBI compared with the US adult population.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included 2 516 189 military veterans meeting the following criteria: (1) served active duty in the US military after 9/11, (2) 18 years or older, and (3) received at least 3 years of care in the Military Health System.3 Veterans with care in the Veteran’s Health Administration were also required to have at least 2 years of care. The cohort was matched with mortality data from the National Death Index from 2006-2020.3 Mortality data from the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention WONDER database4 for 2006-2020 were analyzed for the US adult population. The study was approved by the University of Utah institutional review board, conducted in accordance with applicable Federal regulations, and followed STROBE.

Demographic variables included age (18-24, 25-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64, ≥65 years), biological sex (male or female), and race and ethnicity (American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian/Pacific Islander, Black non-Hispanic, Hispanic, and White non-Hispanic). Veterans were identified as having deployment and TBI exposure (positive screening on Clinical Reminder and Comprehensive TBI Evaluation protocol or medical diagnosis of mild, moderate, severe, or penetrating TBI).3 Suicide cause of death was determined from International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision codes X60-X84.

Adjusted period-specific suicide rates were estimated with multivariable negative binomial regression models reported as mortality rate ratios (MRRs) with 95% CIs, separately for veterans and US adult population. Covariates included year, age groups, sex, race and ethnicity, deployment status, and TBI exposure. Average annual percent change in rates were estimated with log-linear regression models and reported with 95% CI. P values were 2-sided. Data were analyzed using R version 4.2.2 (R Foundation).

Results

A total of 8262 suicide deaths among veterans and 562 411 among the US adult population equated to crude rates of 42.13 and 18.42 per 100 000 person-years, respectively (Table). Suicide rates increased above 2006 levels beginning in 2008 (MRR, 3.20; 95% CI, 1.98-5.45; P < .001) through 2020 for veterans and increased above 2006 levels beginning in 2012 (MRR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.02-1.25; P = .02) through 2020 for the US adult population. Higher suicide rates occurred in veterans with TBI (MRR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.46-1.67; P < .001).

Table. Results of Multivariable Negative Binomial Regression Models of Suicide Mortality Rates from 2006-2020.

| Variable | Veteran cohort | Total US adult population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. at-risk, person-years | MRR (95% CI) | P value | No. at-risk, person-years | MRR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Person-years | 19 608 706 | NA | NA | 3 053 028 440 | NA | NA |

| No. of suicide deaths | 8262 | NA | NA | 562 411 | NA | NA |

| Year | ||||||

| 2006 (Reference) | 364 409 | NA | NA | 181 793 257 | NA | NA |

| 2007 | 616 509 | 1.40 (0.82-2.50) | .23 | 186 438 575 | 1.06 (0.96-1.18) | .26 |

| 2008 | 801 077 | 3.20 (1.98-5.45) | <.001 | 186 207 075 | 1.07 (0.97-1.19) | .18 |

| 2009 | 958 834 | 5.07 (3.19-8.53) | <.001 | 190 963 583 | 1.09 (0.98-1.21) | .11 |

| 2010 | 1 102 419 | 5.35 (3.38-8.97) | <.001 | 193 315 599 | 1.10 (0.99-1.22) | .07 |

| 2011 | 1 231 097 | 6.33 (4.02-10.59) | <.001 | 197 124 128 | 1.11 (1.00-1.23) | .05 |

| 2012 | 1 344 633 | 7.03 (4.48-11.68) | <.001 | 202 428 644 | 1.13 (1.02-1.25) | .02 |

| 2013 | 1 438 512 | 7.41 (4.73-12.30) | <.001 | 204 120 327 | 1.12 (1.01-1.23) | .03 |

| 2014 | 1 521 265 | 7.14 (4.56-11.94) | <.001 | 206 532 317 | 1.16 (1.05-1.28) | .004 |

| 2015 | 1 597 595 | 8.87 (5.67-14.66) | <.001 | 209 300 879 | 1.19 (1.08-1.32) | <.001 |

| 2016 | 1 657 575 | 8.91 (5.70-14.82) | <.001 | 214 019 833 | 1.23 (1.11-1.36) | <.001 |

| 2017 | 1 709 974 | 8.88 (5.68-14.73) | <.001 | 218 627 485 | 1.26 (1.14-1.39) | <.001 |

| 2018 | 1 749 882 | 10.10 (6.45-16.69) | <.001 | 221 403 762 | 1.32 (1.19-1.45) | <.001 |

| 2019 | 1 760 166 | 10.30 (6.60-17.12) | <.001 | 221 915 412 | 1.33 (1.20-1.46) | <.001 |

| 2020 | 1 754 759 | 11.70 (7.48-19.39) | <.001 | 218 837 564 | 1.31 (1.18-1.45) | <.001 |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 18-24 (Reference) | 4 100 163 | NA | NA | 411 064 409 | NA | NA |

| 25-34 | 9 146 972 | 1.33 (1.22-1.46) | <.001 | 567 098 256 | 1.03 (0.97-1.08) | .35 |

| 35-44 | 3 726 530 | 1.36 (1.23-1.51) | <.001 | 536 349 401 | 1.01 (0.96-1.07) | .66 |

| 45-54 | 1 885 434 | 1.13 (1.00-1.27) | .04 | 565 603 316 | 1.06 (1.00-1.13) | .03 |

| 55-64 | 619 646 | 0.76 (0.64-0.91) | .003 | 492 847 635 | 0.98 (0.92-1.04) | .47 |

| ≥65 | 129 961 | 0.42 (0.27-0.62) | <.001 | 480 065 423 | 0.90 (0.84-0.97) | .004 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female (Reference) | 2 725 789 | NA | NA | 1 405 623 809 | NA | NA |

| Male | 16882917 | 2.22 (2.02-2.46) | <.001 | 1 647 404 631 | 3.27 (3.15-3.40) | <.001 |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 354 516 | 0.95 (0.80-1.13) | .58 | 3 962 823 | 2.15 (1.97-2.34) | <.001 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 875 687 | 1.07 (0.96-1.20) | .23 | 84 147 194 | 0.49 (0.46-0.52) | <.001 |

| Black non-Hispanic | 3 054 549 | 0.65 (0.60-0.71) | <.001 | 270 774 365 | 0.44 (0.42-0.46) | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 2 101 895 | 0.63 (0.57-0.70) | <.001 | 362 293 068 | 0.45 (0.43-0.47) | <.001 |

| White non-Hispanic (Reference) | 12 968 618 | NA | NA | 2 331 850 990 | NA | NA |

| Unknown | 253 441 | 0.98 (0.79-1.19) | .82 | NA | NA | NA |

| Deployment history status | ||||||

| Deployed | 14 463 270 | 0.80 (0.75-0.85) | <.001 | NA | NA | NA |

| Not deployed (Reference) | 5 145 436 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| TBI exposure | ||||||

| TBI | 4 682 062 | 1.56 (1.46-1.67) | <.001 | NA | NA | NA |

| No TBI (Reference) | 14 926 644 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: MRR, mortality rate ratio; NA, not applicable; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

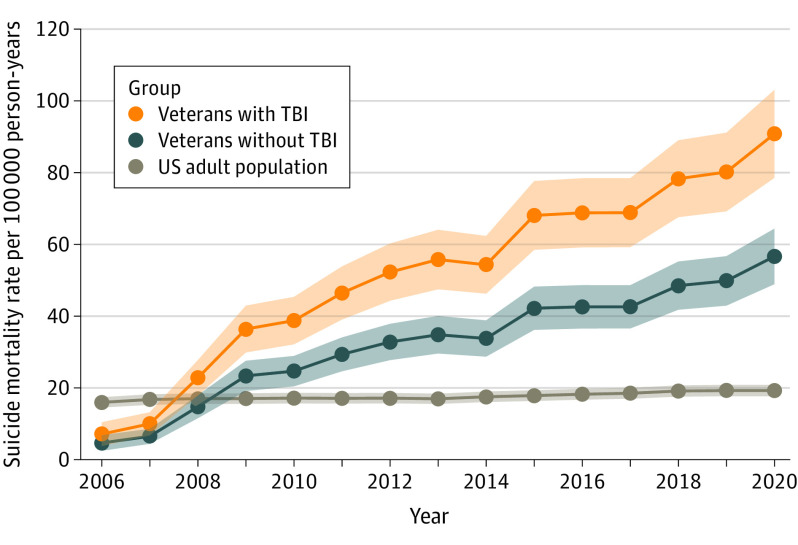

From 2006-2020, suicide rates increased per year by 14.8% (95% CI, 10.5-19.2; P < .001) for veterans with TBI (7.11 to 90.81), 14.4% (95% CI, 10.2-18.7; P < .001) for veterans without TBI (4.65 to 55.65), and 1.2% (95% CI, 0.9-1.4; P < .001) for the US adult population (15.97 to 19.26) (Figure). From 2019-2020, suicide rates per 100 000 person-years increased from 80.16 to 90.81 for veterans with TBI and from 49.82 to 56.65 for veterans without TBI but did not change in the US adult population (19.26).

Figure. Adjusted Suicide Mortality Rates per 100 000 Person-Years From 2006-2020.

Average annual percentage change was 14.8% (95% CI, 10.5-19.2; P < .001) for veterans with traumatic brain injuries (TBIs), 14.4% (95% CI, 10.2-18.7; P < .001) for veterans without TBI, and 1.2% (95% CI, 0.9-1.4; P < .001) for the US adult population.

Discussion

In a large cohort of US military veterans serving after 9/11, suicide rates increased more than 10-fold from 2006-2020, a significantly greater rate of change than in the US adult population. Potential explanations for increases in suicide include increased risk of mental health diagnoses, substance misuse, and gun violence.5,6 Over the 15-year period, veterans with TBI had suicide rates 56% higher than veterans without TBI and 3 times higher than the US adult population. Limitations include potential misclassification of causes of death, underreporting of TBI exposure, exclusion of veterans not seeking care in the Military Health System or Veteran’s Health Administration, and residual confounding due to differences between the veteran and US adult population.

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.2022 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. VA Suicide Prevention, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention . Published September 2022. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2022/2022-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-FINAL-508.pdf"https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2022/2022-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-FINAL-508.pdf.2022"

- 2.DOD TBI worldwide numbers. US Department of Defense. Published 2021. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Centers-of-Excellence/Traumatic-Brain-Injury-Center-of-Excellence/DOD-TBI-Worldwide-Numbers

- 3.Howard JT, Stewart IJ, Amuan M, Janak JC, Pugh MJ. Association of traumatic brain injury with mortality among military veterans serving after September 11, 2001. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2148150-e2148150. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC Wonder. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Published 2023. Accessed March 9, 2023. https://wonder.cdc.gov

- 5.Walker LE, Watrous J, Poltavskiy E, et al. Longitudinal mental health outcomes of combat-injured service members. Brain Behav. 2021;11(5):e02088. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adler AB, Britt TW, Castro CA, McGurk D, Bliese PD. Effect of transition home from combat on risk-taking and health-related behaviors. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24(4):381-389. doi: 10.1002/jts.20665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data sharing statement