This randomized clinical trial investigates the long-term efficacy of mavacamten in reducing the need for septal reduction therapy in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Key Points

Question

What is the longer-term efficacy of mavacamten in reducing the need for septal reduction therapy (SRT) in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)?

Findings

Results of A Study to Evaluate Mavacamten in Adults With Symptomatic Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Who Are Eligible for Septal Reduction Therapy (VALOR-HCM), a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of 112 patients with symptomatic HCM, showed that at week 56, 5 of 56 patients (8.9%) in the original mavacamten group and 10 of 52 patients (19.2%) in the placebo crossover group met composite SRT criteria, and 96 of 108 patients (89%) continued taking mavacamten long term.

Meaning

Study results show that for patients with symptomatic obstructive HCM, there is sufficient and sustained improvement with mavacamten, thereby reducing the need for SRT and representing a useful therapeutic option for patients.

Abstract

Importance

There is an unmet need for novel medical therapies before recommending invasive therapies for patients with severely symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Mavacamten has been shown to improve left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) gradient and symptoms and may thus reduce the short-term need for septal reduction therapy (SRT).

Objective

To examine the cumulative longer-term effect of mavacamten on the need for SRT through week 56.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, randomized clinical trial with placebo crossover at 16 weeks, conducted from July 2020 to November 2022. Participants were recruited from 19 US HCM centers. Included in the trial were patients with obstructive HCM (New York Heart Association class III/IV) referred for SRT. Study data were analyzed April to August 2023.

Interventions

Patients initially assigned to mavacamten at baseline continued the drug for 56 weeks, and patients taking placebo crossed over to mavacamten from week 16 to week 56 (40-week exposure). Dose titrations were performed using echocardiographic LVOT gradient and LV ejection fraction (LVEF) measurements.

Main Outcome and Measure

Proportion of patients undergoing SRT, remaining guideline eligible or unevaluable SRT status at week 56.

Results

Of 112 patients with highly symptomatic obstructive HCM, 108 (mean [SD] age, 60.3 [12.5] years; 54 male [50.0%]) qualified for the week 56 evaluation. At week 56, 5 of 56 patients (8.9%) in the original mavacamten group (3 underwent SRT, 1 was SRT eligible, and 1 was not SRT evaluable) and 10 of 52 patients (19.2%) in the placebo crossover group (3 underwent SRT, 4 were SRT eligible, and 3 were not SRT evaluable) met the composite end point. A total of 96 of 108 patients (89%) continued mavacamten long term. Between the mavacamten and placebo-to-mavacamten groups, respectively, after 56 weeks, there was a sustained reduction in resting (mean difference, −34.0 mm Hg; 95% CI, −43.5 to −24.5 mm Hg and −33.2 mm Hg; 95% CI, −41.9 to −24.5 mm Hg) and Valsalva (mean difference, −45.6 mm Hg; 95% CI, −56.5 to −34.6 mm Hg and −54.6 mm Hg; 95% CI, −66.0 to −43.3 mm Hg) LVOT gradients. Similarly, there was an improvement in NYHA class of 1 or higher in 51 of 55 patients (93%) in the original mavacamten group and in 37 of 51 patients (73%) in the placebo crossover group. Overall, 12 of 108 patients (11.1%; 95% CI, 5.87%-18.60%), which represents 7 of 56 patients (12.5%) in the original mavacamten group and 5 of 52 patients (9.6%) in the placebo crossover group, had an LVEF less than 50% (2 with LVEF ≤30%, one of whom died), and 9 of 12 patients (75%) continued treatment.

Conclusions and Relevance

Results of this randomized clinical trial showed that in patients with symptomatic obstructive HCM, mavacamten reduced the need for SRT at week 56, with sustained improvements in LVOT gradients and symptoms. Although this represents a useful therapeutic option, given the potential risk of LV systolic dysfunction, there is a continued need for close monitoring.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04349072

Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a frequently encountered genetic heart disease with an estimated prevalence between 1 in 200 and 500.1,2 Approximately two-thirds of individuals with HCM demonstrate an obstructive phenotype often associated with progressively worsening dyspnea and reduced exercise capacity related to dynamic left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction, concomitant mitral regurgitation, diastolic dysfunction, and hypercontractility. Such patients have an increased risk of heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and sudden arrhythmia–related cardiac death.3,4,5

In patients with symptomatic obstructive HCM who do not respond to traditional medical therapy (β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, or disopyramide), septal reduction therapy (SRT), either surgical myectomy or alcohol septal ablation, provides excellent symptom improvement, improved quality of life, and long-term survival.3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 However, SRT requires experienced surgeons, typically at specialized centers, to achieve optimal results. Even patients cared for at experienced centers may opt for effective medical therapy over an invasive procedure. Hence, there is an unmet need for novel medical therapies as an option for patients before moving to SRT.

In previous studies of patients with symptomatic obstructive HCM, mavacamten, a selective allosteric and reversible cardiac myosin inhibitor, improved the LVOT gradient, symptom burden, and physical functioning.17,18,19 It is now approved for clinical use in patients with symptomatic obstructive HCM in 5 continents. A Study to Evaluate Mavacamten in Adults With Symptomatic Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Who Are Eligible for Septal Reduction Therapy (VALOR-HCM), a phase 3 placebo-controlled trial, reported that the addition of mavacamten to maximally tolerated medical therapy allowed patients with severely symptomatic obstructive HCM to improve sufficiently to not proceed with SRT for up to 32 weeks, and similar results were observed in patients who actively crossed over from placebo after 16 weeks.20,21 However, the effect of longer-term exposure to mavacamten on the need for SRT and safety remains undetermined. In this study from the VALOR-HCM trial, we report the safety and efficacy results through 56 weeks of dose-blinded treatment in patients initially randomly assigned to mavacamten treatment (day 1 to week 56) and patients initially randomly assigned to placebo who crossed over to mavacamten for 40 weeks of exposure (week 16 to week 56). In addition, we also reported the results stratified by sex.

Methods

Study Organization and Oversight

This was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, phase 3 randomized clinical trial conducted from July 2020 to November 2022 at 19 sites in the US.22 The trial was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb (Princeton, New Jersey) and coordinated by Cleveland Clinic Coordinating Center for Clinical Research (C5Research) and Medpace, a contract research organization (Cincinnati, Ohio). Details of the academic oversight, study protocol, and statistical analysis plan are available in Supplement 1 and eAppendix 1 in Supplement 2. The protocol was developed by the sponsor, C5Research, and Medpace and approved by the institutional review boards at participating centers, with all patients providing written informed consent. An independent data monitoring committee had access to unblinded data during the randomized blinded portion of the trial. After the last patient reached week 56 visit (November 2022), the database was locked, and a complete copy was transferred to C5Research, where an independent statistician performed statistical analyses.

Study Population

The trial enrolled patients taking maximally tolerated medical therapy and referred for consideration of SRT, based on 2011 American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines.23 Key inclusion criteria were as follows: age 18 or older and severe dyspnea or chest pain (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class III/IV or class II with exertional syncope or near syncope) despite maximally tolerated medical therapy (including combination therapy and/or disopyramide). Patients from the following self-identified race and ethnicity categories were included: Asian, Black, White, or unspecified/other (included American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, or unknown). Patients had an HCM diagnosis (unexplained hypertrophy with a maximum septal wall thickness determined by a core laboratory of 15 mm or greater or 13 mm or greater with family history of HCM), LVOT gradient at rest or with provocation (Valsalva maneuver or postexercise) of 50 mm Hg or greater, and a documented left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 60% or greater. Patients were referred within the past 12 months for SRT and actively considering scheduling the procedure. Patients could elect to proceed to SRT at any time after randomization. Additional inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in a design manuscript and Supplement 1.22

Study Procedures

Patients were initially randomly assigned 1:1 to oral mavacamten, 5 mg, per day or placebo, stratified by SRT type (myectomy or alcohol ablation) and NYHA class. During the double-blind and active-controlled period, echocardiography was performed every 4 weeks and used to titrate drug dosage based on LVEF and LVOT gradient measured by the core laboratory at the Cleveland Clinic (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2). After week 16, patients initially randomly assigned to placebo crossed over to receive mavacamten, 5 mg, daily via the interactive response system, and dose-blinded titration was performed as in the patients originally randomly assigned to mavacamten. Patients initially randomly assigned to mavacamten continued the same dose as week 16 with 4 weekly assessments to week 32. Patients who were part of the placebo crossover group started mavacamten, 5 mg, at week 16 and underwent dose titration at weeks 20, 24, and 28. After week 28, dose adjustment was allowed for persistently elevated LVOT gradients, with monitoring visits conducted every 12 weeks after week 32. If the LVEF fell below 50% during treatment, mavacamten was temporarily interrupted with follow-up in 2 to 4 weeks. If LVEF was 50% or greater at that time, mavacamten was restarted at 1 lower dose level. If the LVEF decreased to 30% or lower, mavacamten was permanently discontinued.20,21,22 Until week 32, the patients and study staff remained blinded to the original treatment assignment and mavacamten dose, and blinded core laboratory LVEF and LVOT gradients were used for drug titration. After 32 weeks, the patients and study staff remained blinded to the original treatment assignment and dose of mavacamten, but dose titrations were based on site-read LVEF measurements and LVOT gradients.

Study End Points

The current study reports 56 weeks of drug exposure (original mavacamten group) or 40 weeks (16-56 weeks) of drug exposure for patients in the placebo crossover group. The efficacy end point was the composite of a decision to proceed with SRT or eligibility for SRT according to the 2011 AHA/ACC guidelines.23 Patients who discontinued the study or whose response status could not be assessed at week 56 were classified as SRT eligible (mavacamten treatment failure). Additional end points included the changes from baseline in postexercise LVOT gradient, NYHA class, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire 23-item Clinical Summary Score (KCCQ-23 CSS), N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level, and cardiac troponin I level. Echocardiographic end points included changes from baseline in LV mass index, LV systolic and diastolic volume index, left atrial volume index, and septal E/e′ (LV filling pressures). Safety outcomes included incidence LVEF less than 50%, death, hospitalization for heart failure, and atrial fibrillation, or ventricular tachyarrhythmia.

Statistical Analysis

The analysis includes all patients initially randomly assigned to mavacamten and patients randomly assigned to placebo who crossed over to mavacamten at week 16. Categorical variables are reported as numbers and percentages. The efficacy outcome was the proportion of patients at week 56 meeting SRT eligibility or deciding to proceed with SRT summarized as number and percentage. For patients taking placebo who crossed over to mavacamten, the week 16 pretreatment value was used as a baseline for NYHA class assessment, laboratory measurements, and echocardiographic measurements. At baseline, continuous variables are presented as mean (SD) if normally distributed or median (IQR) if not normally distributed. Changes from baseline for echocardiographic variables are summarized using mean and 95% CIs, and changes from baseline in NT-proBNP and troponin I levels are reported as median and distribution-free 95% CIs. Spearman correlation coefficients are reported for core-laboratory and site-based echocardiographic measurements. A post hoc analysis by sex on the efficacy end point, change in NYHA class, and LVOT gradient is presented using descriptive statistics. Analysis was performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Study data were analyzed April to August 2023.

Results

Study Population

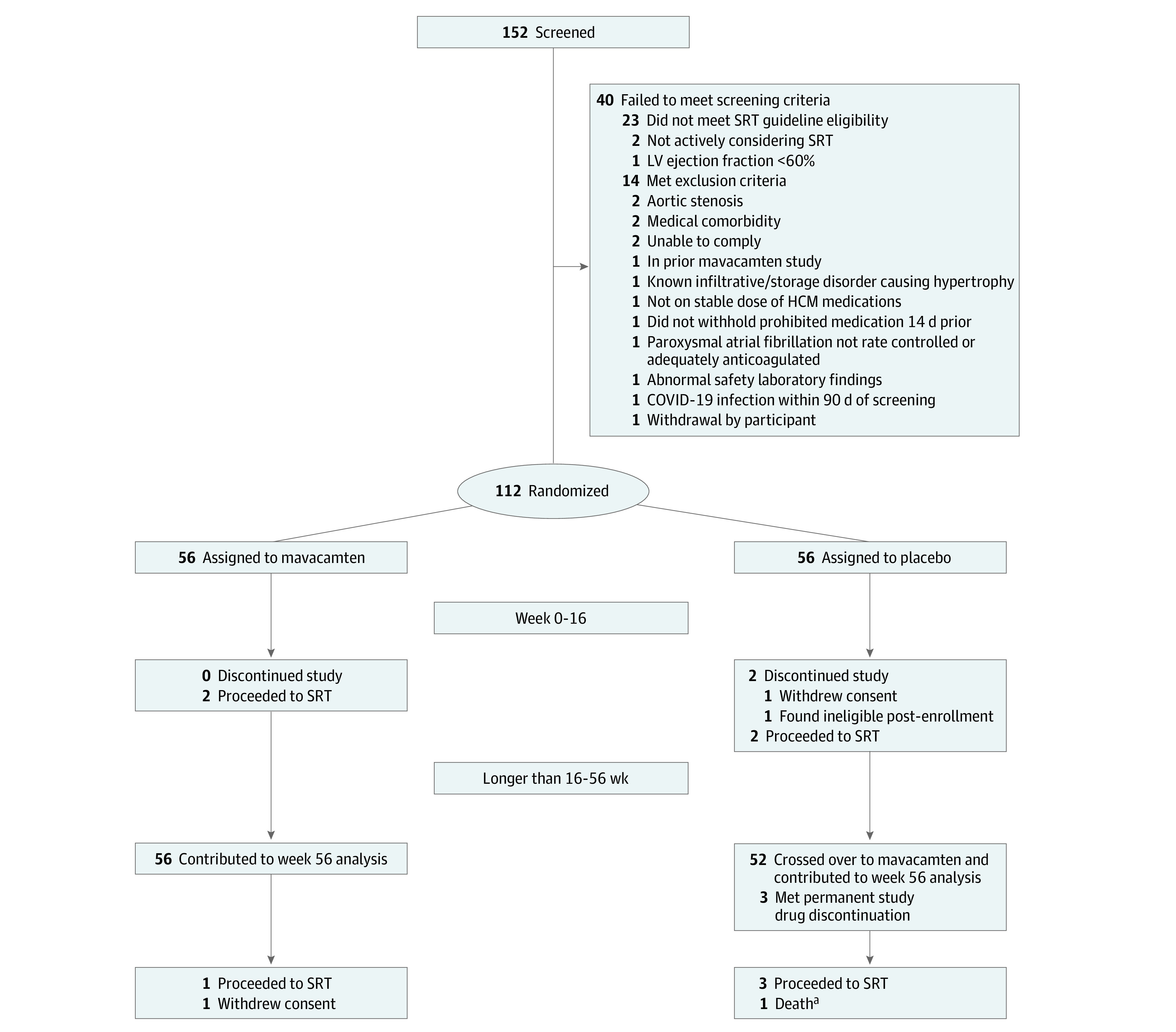

Of 112 patients with highly symptomatic obstructive HCM,20 108 (mean [SD] age, 60.3 [12.5] years; 54 male [50.0%]; 54 female [50.0%]) qualified for week 56 evaluation. The flowchart of patients is shown in Figure 1. All patients initially randomly assigned to mavacamten (56 [51.9%]), and those who crossed over from placebo to mavacamten after 16 weeks (52 [48.1%]) were included. Patients self-identified with the following race and ethnicity categories: 2 Asian (1.9%), 3 Black (2.8%), 96 White (88.9%), 1 American Indian or Alaska Native (0.9%), and 6 unknown (5.6%).

Figure 1. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Diagram Detailing the Recruitment, Randomization, and Patient Flow in the 56-Week Long-Term Extension Trial A Study to Evaluate Mavacamten in Adults With Symptomatic Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Who Are Eligible for Septal Reduction Therapy (VALOR-HCM).

aAlso met permanent study drug discontinuation criteria.

The 4 patients excluded from the original placebo group included 2 patients who underwent SRT during the first 16 weeks and 2 who discontinued the study early.20 All patients were symptomatic (102 of 108 [94.4%] NYHA class III/IV) while taking maximally tolerated HCM therapy, with most taking β-blocker monotherapy (49 of 108 [45.4%]). Mean (SD) LVEF was 68% (4%) and peak resting, Valsalva, and postexercise LVOT gradients were 50 (31) mm Hg, 77 (30) mm Hg, and 84 (35) mm Hg, respectively. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Key baseline characteristics, separated on the basis of sex, are shown in eTable 1 in Supplement 2. At week 56, 70 of 108 patients (64.8%) received 5 or 10 mg of mavacamten (eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Table 1. Patient Characteristics of the Trial Population.

| Characteristic | Placebo to mavacamten (n = 52) | Original mavacamten (n = 56) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 60.9 (10.4) | 59.8 (14.2) |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||

| Male | 25 (48.1) | 29 (51.8) |

| Female | 27 (51.9) | 27 (48.2) |

| Race, No. (%)a | ||

| Asian | 0 | 2 (3.6) |

| Black | 0 | 3 (5.4) |

| White | 48 (92.3) | 48 (85.7) |

| Unspecified or other | 4 (7.7) | 3 (5.4) |

| Vital signs, mean (SD) | ||

| Body mass indexb | 32.1 (6.3) | 29.3 (4.8) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 130.3 (16.4) | 130.4 (16.5) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 73.7 (8.9) | 74.0 (10.5) |

| Duration of obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy disease, mean (SD), y | 6.8 (7.5) | 7.5 (9.4) |

| Medical history, No. (%) | ||

| Family history of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 15 (28.9) | 17 (30.4) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 7 (13.5) | 11 (19.6) |

| Hypertension | 32 (61.5) | 36 (64.3) |

| Syncope or presyncope | 28 (53.8) | 29 (51.8) |

| Internal cardioverter defibrillator | 10 (19.2) | 9 (16.1) |

| New York Heart Association functional class, No. (%) | ||

| Class II with exertional syncope | 2 (3.8) | 4 (7.1) |

| Class III or higher | 50 (96.2) | 52 (92.9) |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy genotype | ||

| At least 1 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant | 10/49 (20.4) | 14/51 (27.5) |

| At least 1 variant of uncertain significance | 13/49 (26.5) | 10/51 (19.6) |

| At least 1 benign or negative result | 30/49 (61.2) | 32/51 (62.7) |

| Type of septal reduction therapy recommended, No. (%) | ||

| Alcohol septal ablation | 5 (9.6) | 8 (14.3) |

| Myectomy | 47 (90.4) | 48 (85.7) |

| Background hypertrophic cardiomyopathy therapy, No. (%) | ||

| Beta blocker monotherapy | 23 (44.2) | 26 (46.4) |

| Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blocker monotherapy | 10 (19.2) | 7 (12.5) |

| Disopyramide monotherapy | 1 (1.9) | 0 |

| β-Blocker and calcium channel blocker | 10 (19.2) | 6 (10.7) |

| β-Blocker and disopyramide | 4 (7.7) | 11 (19.6) |

| Calcium channel blocker and disopyramide | 2 (3.9) | 1 (1.8) |

| β-Blocker, calcium channel blocker and disopyramide | 1 (1.9) | 2 (3.6) |

| None (medication intolerance) | 1 (1.9) | 3 (5.4) |

| Echocardiographic parameters, mean (SD) | ||

| LVOT gradient, mm Hg | ||

| Resting | 46.6 (29.1) | 51.2 (31.4) |

| Valsalva | 79.3 (29.8) | 75.3 (30.8) |

| Postexercise | 82.9 (36.7) | 82.5 (34.7) |

| LV ejection fraction, % | 68.4 (2.4) | 68.0 (3.8) |

| Left atrial volume index, mL/m2 | 40.3 (15.3) | 41.3 (16.5) |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 120.0 (33.3) | 119.2 (29.5) |

| Septal E/e′ | 18.1 (7.9) | 19.6 (9.1) |

| LV end-systolic volume index, mL/m2 | 15.5 (3.5) | 15.9 (5.1) |

| LV end-diastolic volume index, mL/m2 | 49.2 (10.1) | 49.1 (13.2) |

| KCCQ-23 CSS points, mean (SD)c | 67.6 (18.7) | 69.5 (16.3) |

| Laboratory measurements, median (IQR) | ||

| NT-proBNP, ng/L | 706 (372-1318) | 724 (291-1913) |

| Cardiac troponin I, ng/L | 13.2 (6.6-27.4) | 17.3 (7.1-31.6) |

| Cardiac troponin T, ug/L | 0.012 (0.01-0.02) | 0.014 (0.01-0.02) |

Abbreviations: KCCQ-23 CSS, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire 23-item Clinical Summary Score; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide.

SI conversion factor: To convert cardiac troponin I to micrograms per liter, divide by 1000 and multiply by 1; to convert cardiac troponin T to nanograms per milliliter, divide by 1; to convert NT-proBNP to picograms per milliliter, divide by 1.

Race was self-reported. The following races/ethnicities were included in the other group: American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, or unknown.

Body mass index is calculated as body weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters.

The KCCQ-23 CSS ranges from 0 to 100 points, where higher scores reflect better health status.

Study End Points

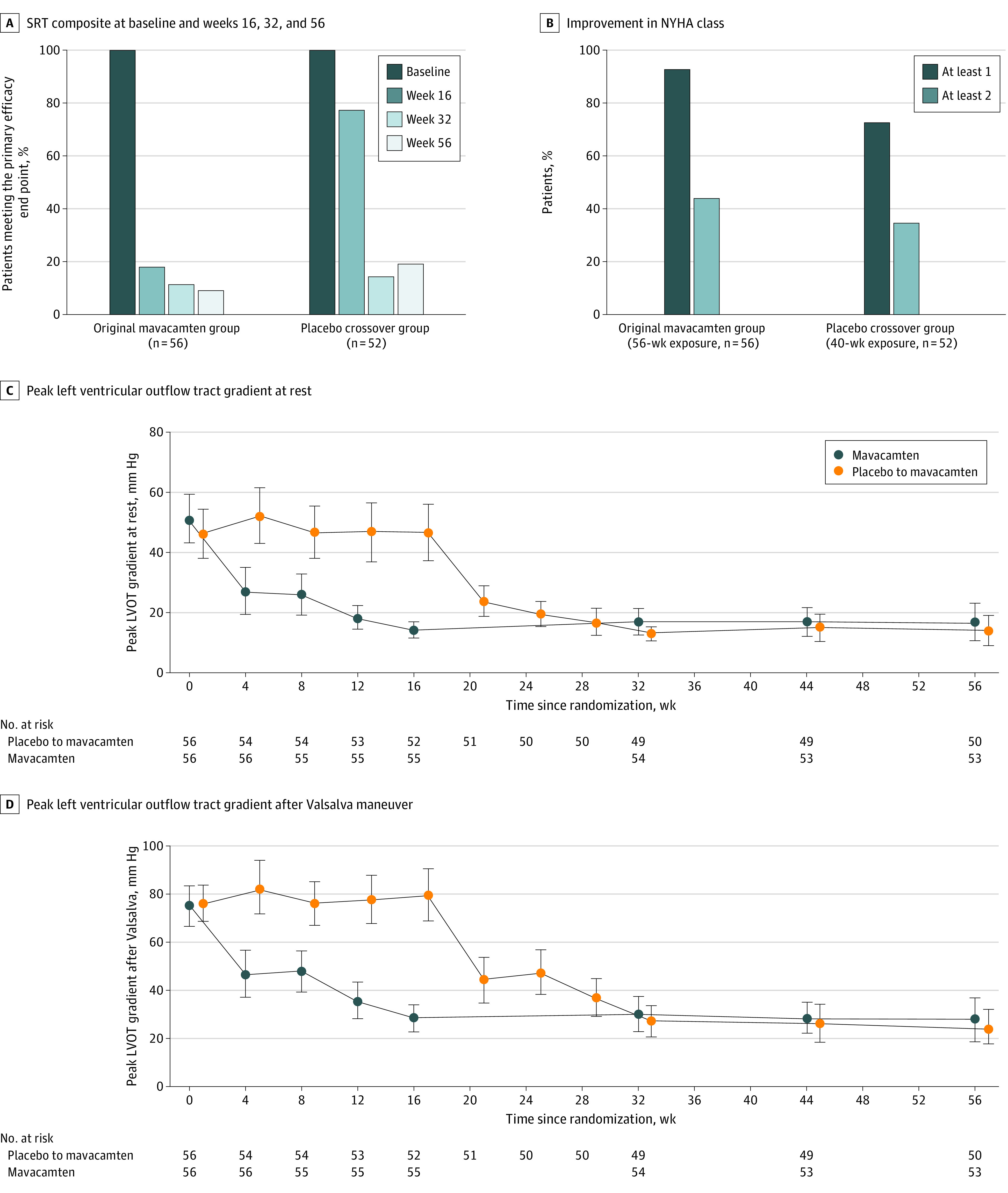

At week 56, 5 of 56 patients (8.9%) in the original mavacamten group (3 underwent SRT, 1 was SRT eligible, and 1 was not SRT evaluable) and 10 of 52 patients (19.2%) in the placebo crossover group (3 underwent SRT, 4 were SRT eligible, and 3 were not SRT evaluable) continued to meet the composite efficacy end point (Table 2 and Figure 2A). Of these, only 3 of 56 patients (5.4%) from the original mavacamten group and 3 of 52 patients (5.8%) from the placebo crossover group chose to undergo SRT. One patient withdrew consent, 1 discontinued treatment at week 32 and did not have echocardiography performed at week 56, 1 was removed for noncompliance, and 3 met criteria for permanent drug discontinuation, leaving 96 of 108 patients (89%) who continued to follow up to 56 weeks. Between the mavacamten and placebo-to-mavacamten groups, respectively, after 56 weeks, there was a sustained reduction in resting (mean difference, −34.0 mm Hg; 95% CI, −43.5 to −24.5 mm Hg and −33.2 mm Hg; 95% CI, −41.9 to −24.5 mm Hg) and Valsalva (mean difference, −45.6 mm Hg; 95% CI, −56.5 to −34.6 mm Hg and −54.6 mm Hg; 95% CI, −66.0 to −43.3 mm Hg) LVOT gradients (Table 3).

Table 2. Primary Efficacy Outcome in the Triala.

| Study weekb | No. | Weeks of mavacamten exposure | Decision to proceed with SRT | SRT eligible based on guideline criteria | SRT eligibility status not evaluable | Composite primary efficacy end point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized to placebo and crossover to treatment at week 16 | ||||||

| 16 | 56 | 0 | 2 (3.6)b | 39 (69.6) | 2 (3.6)b | 43 (76.8) |

| 32 | 52 | 16 | 2 (3.8) | 3 (5.8) | 2 (3.8) | 7 (13.5) |

| 56 | 52 | 40c | 3 (5.6) | 4 (7.7) | 3 (5.8)d | 10 (19.2) |

| Randomized to mavacamten | ||||||

| 16 | 56 | 16 | 2 (3.6) | 8 (14.3) | 0 | 10 (17.9) |

| 32 | 56 | 32 | 3 (5.4) | 2 (3.6) | 1 (1.8) | 6 (10.7) |

| 56 | 56 | 56 | 3 (5.4) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.8)e | 5 (8.9) |

Abbreviation: SRT, septal reduction therapy.

Results are cumulative through the reported study week. In the placebo crossover group, at the week 56 assessment, 10 patients met the primary efficacy end point (composite of patients who proceeded to SRT, were guideline eligible for SRT, and whose SRT status could not be evaluated; 1 patient was guideline eligible, 1 patient proceeded to SRT, and 1 patient had an SRT status that was not evaluable, for a net increase in 3 patients between week 32 and week 56). Similarly, in the original mavacamten group, 6 patients met the composite end point at week 32. By week 52, 1 patient no longer met guideline-based SRT eligibility criteria for a net reduction in 1 eligible patient meeting the primary efficacy end point.

A total of 4 patients randomly assigned to placebo were excluded from further analysis after the double-blind period (week 0-16). Two patients decided to proceed with SRT, 1 patient withdrew consent, and 1 patient was found ineligible before the week 16 visit.

Average exposure duration to mavacamten at the week 56 visit for those receiving placebo for the first 16 weeks (double-blind period).

One patient was withdrawn by a study investigator because of noncompliance at week 20, 1 patient had left ventricular ejection fraction less than 30% at week 56 and was unable to exercise and did not have echocardiographic data collected (subsequently died), and 1 patient discontinued treatment at week 32 and did not have echocardiographic testing performed at week 56.

Patient withdrew consent at week 28.

Figure 2. Efficacy and Safety Parameters From Baseline to Week 56 for the Original Mavacamten and the Placebo Crossover Groups.

A, Septal reduction therapy (SRT) composite at baseline, weeks 16, 32, and 56. B, Improvement in New York Heart Association class. C, Peak left ventricular outflow tract gradient at rest. D, Peak left ventricular outflow tract gradient after Valsalva maneuver. Plotted values in panels B to D represent means and SEs.

Table 3. Change in Functional, Laboratory, and Echocardiographic Parameters.

| Parameter | Placebo, double-blind period, week 0-16 (n = 56) | Placebo to mavacamten, active-controlled period plus LTE, week 16-56 (n = 52) | Mavacamten | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Double-blind period, week 0-16 (n = 56) | Active-controlled period plus LTE, week 16-56 (n = 56) | Total exposure, week 0-56 (n = 56) | |||

| Change in resting LVOT gradient, mean (95% CI), mm Hg | −1.5 (−8.8 to 5.8) | −33.2 (−41.9 to −24.5) | −36.0 (−43.8 to −28.2) | 2.3 (−3.4 to 7.9) | −34.0 (−43.5 to −24.5) |

| Change in Valsalva LVOT gradient, mean (95% CI), mm Hg | 0.4 (−7.8 to 8.6) | −54.6 (−66.0 to −43.3) | −45.2 (−52.9 to −37.5) | −0.02 (−7.8 to 7.8) | −45.6 (−56.5 to −34.6) |

| Change in postexercise LVOT gradient, mean (95% CI), mm Hg | −1.8 (−9.8 to 6.1) | −49.4 (−61.9 to −36.9) | −39.1 (−48.9 to −29.2) | −3.7 (−12.1 to 4.8) | −43.4 (−55.9 to −30.9) |

| At least 1 class of NYHA improvement, No./total No. (%)a | 12/56 (21.4) | 37/51 (72.6) | 35/56 (62.5) | NA | 51/55 (92.7) |

| At least 2 classes of NYHA improvement, No./total No. (%)a | 1/56 (1.8) | 18/51 (35.3) | 15/56 (26.8) | NA | 24/55 (43.6) |

| Change in KCCQ-23-CSS, mean (95% CI) | 1.9 (−1.5 to 5.2) | 11.7 (6.9 to 16.4) | 10.4 (6.0 to 14.7) | 3.1 (−0.8 to 7.1) | 14.1 (9.9 to 18.3) |

| Change in NT-proBNP, median (95% CI), ng/Lb | 40 (−155 to 203) | −423 (−624 to −252) | −399 (−1146 to −138) | −21 (−57 to 11) | −376 (−723 to −225) |

| Change in cardiac troponin I, median (95% CI), ng/Lb | 0.07 (−2.0 to 3.3) | −6.2 (−11.5 to −3.3) | −9.2 (−18.1 to −1.8) | −0.4 (−1.9 to 0.8) | −7 (−10 to −2.3) |

| Change in additional echocardiographic parameters, mean (95% CI) | |||||

| Change in LV ejection fraction, mean (95% CI), % | 0.3 (−0.8 to 1.5) | −4.0 (−6.1 to −1.9) | −3.4 (−5.0 to −1.7) | −1.1 (−3.0 to 0.8) | −4.0 (−5.5 to −2.5) |

| Change in LV filling pressures (E/e′ ratio), mean (95% CI) | 0.7 (−0.6 to 2.1) | −3.6 (−5.8 to −1.5) | −3.3 (−4.9 to −1.7) | −0.8 (−1.9 to 0.3) | −4.1 (−5.7 to −2.6) |

| Change in LV stroke volume index mean (95% CI), ml/m2 | 0.14 (−1.7 to 2.0) | −2.0 (−4.4 to 0.3) | −1.4 (−3.4 to 0.5) | −1.3 (−3.6 to 1.0) | −3.0 (−5.1 to −0.9) |

| Change in left atrial volume index, mean (95% CI), mL/m2 | −0.5 (−2.8 to 1.7) | −5.3 (−7.6 to −2.9) | −5.2 (−7.4 to −3.1) | −0.2 (−2.6 to 2.2) | −5.5 (−8.4 to −2.6) |

| Change in LV end-systolic volume index, mL/m2 | 0.1 (−1.0 to 1.2) | 2.7 (0.5 to 4.9) | 1.4 (0.3 to 2.5) | −0.1 (−1.7 to 1.5) | 1.3 (−0.04 to 2.6) |

| Change in LV end-diastolic volume index, mL/m2 | 0.19 (−2.6 to 2.9) | 0.6 (−3.0 to 4.3) | 0.01 (−2.5 to 2.5) | −1.6 (−4.8 to 1.6) | −1.9 (−5.0 to 1.3) |

| Change in LV mass index, g/m2 | −1.9 (−6.8 to 2.9) | −14.5 (−20.8 to −8.3) | −7.9 (−12.9 to −2.9) | −4.9 (−8.9 to −0.8) | −11.5 (−16.8 to −6.2) |

Abbreviations: E/e′ ratio, peak E-wave velocity/peak e’ velocity; KCCQ-23 CSS, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire 23-item Clinical Summary Score; LTE, long-term extension; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; NA, not applicable; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

SI conversion factor: To convert cardiac troponin I to micrograms per liter, divide by 1000 and multiply by 1; to convert NT-proBNP to picograms per milliliter, divide by 1.

Of the 35 patients with an improvement of 1 NYHA class at week 16, 1 no longer had improvement, and 1 had a missing NYHA assessment. An additional 18 patients had an improvement of 1 NYHA class between weeks 16 and 56. Of the 15 patients with an improvement of 2 NYHA classes at week 16, 1 patient moved from NYHA class I to class II by week 56, and 1 had a missing week 56 NYHA assessment. An additional 11 patients had an improvement of 2 NYHA classes from week 16 to 56.

Distribution-free 95% CI.

In the original mavacamten group, 51 of 55 patients (92.7%) demonstrated an NYHA class improvement of 1 class or higher, and 24 of 55 patients (43.6%) demonstrated an NYHA class improvement of 2 classes or higher by week 56 (Table 3 and Figure 2B). In the placebo crossover group, 37 of 51 patients (72.5%) had an NYHA class improvement of 1 class or higher, and 18 of 51 patients (35.3%) had an NYHA class improvement of 2 classes or higher at week 56 (40-week exposure). Data on additional functional, laboratory, and hemodynamic parameter improvements from baseline are shown in Table 3, Figure 2C-D, and eFigure 2A-F in Supplement 2 and were sustained up to week 56. The effect of mavacamten on SRT eligibility, NYHA class improvement, and LVOT gradients was similar in both sexes (eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

The data on patients who chose to undergo SRT are shown in eTable 4 in Supplement 2. Three patients remain in NYHA class II to III despite SRT, one of whom needed a second alcohol septal ablation, and 1 had residual LVOT gradient greater than 50 mm Hg after myectomy. The data on 5 patients who remained eligible but chose not to undergo SRT are shown in eTable 5 in Supplement 2. At week 56, a total of 20 patients (15 in original mavacamten group and 5 in placebo crossover group) were able to reduce background HCM therapy dosages, as shown in eTable 6 in Supplement 2.

Safety

Safety outcomes, including LVEF changes and adverse events, are shown in eTable 7 and eFigure 3 in Supplement 2. Between weeks 32 and 56, echocardiograms were evaluated at individual sites, in addition to the core laboratory. The correlation in LVEF and LVOT gradients between core laboratory and site measurements is shown in eTable 8 and eFigure 4 in Supplement 2.

In total, 12 of 108 patients (11.1%; 95% CI, 5.87%-18.60%) developed LVEF less than 50% (2 with LVEF ≤30%, one of whom died) during the follow-up period, and 9 of 12 patients (75%) continued treatment. This includes 7 of 56 patients (12.5%) in the original mavacamten group followed up for 56 weeks and 5 of 52 patients (9.6%) in the placebo crossover group followed up for 40 weeks.

In 2 of 52 patients (3.8%) of the original placebo group, mavacamten was permanently discontinued due to LVEF less than 30%. One patient had a heart failure admission with atrial fibrillation at 31 weeks for whom LVEF normalized after drug discontinuation and cardioversion. The second patient had LVEF less than 30% measured on site at week 56 when mavacamten was discontinued. This patient continued taking disopyramide and verapamil, was evaluated by a pulmonologist, and died suddenly before week 60. Details of both patients are described in eAppendix 2 in Supplement 2. In 1 patient from the original placebo crossover group (taking mavacamten, 2.5 mg), LVEF was 49% at week 32, and the patient was again prescribed mavacamten, 2.5 mg daily. However, at week 56, the LVEF was measured to be less than 50% a second time, triggering permanent mavacamten discontinuation. The LVEF normalized after discontinuation, and the patient did not undergo SRT at week 56. The remaining 9 patients required temporary drug interruption due to LVEF level greater than 30% but less than 50% (median [range], 45% [38%-49%]). These patients had undergone increases in doses during the first 12 weeks for those in the original mavacamten group, or between weeks 16 and 28 in the placebo crossover group. Due to LVEF less than 50%, they were restarted on a lower dose (10, 5, or 2.5 mg dependent on the prior dose) after a 2- to 4-week pause, and improvement in LVEF to greater than 50%. These patients remained asymptomatic in the follow-up period and continued treatment. There were no ventricular tachyarrhythmias resulting in defibrillation in either group. Additional treatment-emergent adverse events are shown in eTable 6 in Supplement 2.

Discussion

The current results from the VALOR-HCM trial demonstrate the effects of mavacamten through 56 weeks in patients initially randomly assigned to mavacamten (56-week exposure) and patients originally randomly assigned to placebo who crossed over to mavacamten at week 16 (40-week exposure). At week 56, there was a sustained therapeutic effect, with only 6 patients (5.6%) undergoing SRT and 96 (89%) remaining in the long-term extension phase. Of the 39 patients in the placebo group who were eligible for SRT at week 16, only 4 remained SRT eligible after switching to mavacamten. Of the 8 patients in the original mavacamten group who were eligible for SRT at week 16, only 1 remained eligible at 56 weeks. These findings suggest a strong preference of the patients enrolled in this trial for medical therapy over invasive procedures. The reduction in SRT eligibility, improvement in NYHA class, and LVOT gradients were similar in both sexes.

In both groups, there was a sustained improvement in resting and provoked LVOT gradients, NYHA class, biomarkers, E/e′, LV mass index, left atrial volume, and KCCQ-23 CSS scores at week 56. Also, 93% of the original mavacamten group demonstrated an NYHA class improvement of 1 class or higher, and 44% showed an NYHA class improvement of 2 classes or higher from baseline vs week 16 results, which showed 64% and 27% with improvement of 1 and 2 NYHA classes, respectively.20 After 40-week exposure, 73% of patients in the original placebo group demonstrated an NYHA class improvement of 1 or higher, and 35% showed an NYHA class improvement of 2 or higher after crossover to mavacamten. These findings suggest favorable consequences of reduced LVOT gradient and/or lusitropic effects of mavacamten.18,24

The downstream consequences of obstructive HCM are primarily a result of asymmetric LV hypertrophy with systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve causing mitral regurgitation and dynamic LVOT obstruction.3,4,23,25 Obstructive HCM is further complicated by a smaller, hypercontractile, less compliant LV with concomitant diastolic dysfunction. Mavacamten directly inhibits myosin to reduce myocardial contractility and improve ventricular compliance.17 Reducing excessive contractility reduces dynamic LVOT obstruction and may also improve lusitropic ventricular properties, as previously shown in this trial population.24

Because of the mechanism of action, avoiding excessive reduction in LV systolic function requires careful monitoring for patient safety. Although prior studies used pharmacokinetics to guide dose adjustments,18 the VALOR-HCM trial used echocardiography (core-laboratory reads in the first 32 weeks and site reads for the remainder) for dose titration and safety assessment, a more practical and widely available approach than titration based on drug concentrations.22 There was significant correlation of LVEF and LVOT gradients, between site-read and core-laboratory read echocardiograms (eTable 8 in Supplement 2), suggesting that such a strategy may be safe in clinical practice.

It is noteworthy that 11% of patients developed LVEF less than 50% during the course of this study, which underscores the need for careful monitoring and additional long-term safety data. Although 10 patients who were treated with mavacamten had a temporary interruption of therapy for reduction in LVEF, they remained asymptomatic and resumed treatment at a lower dose, and the LVEF recovered (1 patient developed LVEF <50% after resumption of mavacamten a second time, necessitating permanent discontinuation). Two additional patients in the placebo crossover group met the criteria for permanent discontinuation after mavacamten initiation, 1 of whom died suddenly.

Based on safety concerns, mavacamten is approved for commercial use in US under the risk evaluation and mitigation strategy requiring frequent monitoring of LVEF. Future studies may help determine whether the prolonged administration of mavacamten (including at potentially lower doses) can result in similar sustained reduction in the need for SRT while maintaining an acceptable long-term safety profile.

Current therapies, such as β-blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, and/or disopyramide, improve symptoms in some patients, but their effects can be modest. Many such therapies have significant adverse effects resulting in intolerance and discontinuation. In the current study, almost 1 in 5 patients could reduce background HCM therapies by week 56 (eTable 6 in Supplement 2). Also, other than a small study of metoprolol, none of these drugs have been studied in randomized clinical trials.26,27 SRT is often recommended for patients with obstructive HCM who remain symptomatic despite maximal medical therapy.3,4,5 Although mavacamten must be used carefully, the ability to defer SRT in most patients for more than 1 year indicates a favorable balance of benefit to risk given the invasive nature of alternative treatments. However, understanding patient preferences regarding the choice of SRT vs mavacamten will be important, especially with more mainstream use of this drug after regulatory approval. The effect of mavacamten on the longer-term need for SRT and safety remains to be determined. Future cost-benefit analyses will also help guide treatment algorithms.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. The efficacy end point was driven by reduction in guideline eligibility for SRT rather than the decision of patients not to proceed with SRT. However, 89% of patients chose not to undergo SRT and currently remain in the long-term extension study. Whether mavacamten can provide the long-term benefits comparable with those achieved with SRT cannot be assessed with the limited sample size and duration of this trial. The current study also included predominantly White patients treated at high-volume HCM centers with established good outcomes for SRT procedures.

Conclusions

Results of the VALOR-HCM randomized clinical trial found that in highly symptomatic patients with obstructive HCM, regardless of sex, mavacamten reduced the long-term need for SRT with sustained improvements in LVOT gradients, symptoms, and quality of life, in addition to favorable cardiac remodeling up to week 56. Mavacamten may provide an alternative for patients with obstructive HCM refractory to medical treatment, which may obviate the need for SRT in many patients. However, given the potential for LV systolic dysfunction, seen in 11% patients in the current study, safety and efficacy require continued monitoring. Also, longer-term studies evaluating the effect of mavacamten on outcomes are needed.

Trial Protocol.

eAppendix 1.

eTable 1. Key Baseline Patient Characteristics, Separated by Sex

eTable 2. Final Dosing Chart for the Study in Both Groups

eTable 3. Select End Points for 40 and 56 Weeks of Exposure to Mavacamten, Separated by Sex

eTable 4. Data on Patients Proceeding to SRT

eTable 5. Week 56 Data on Eligible Patients Who Did Not Choose to Undergo SRT

eTable 6. Dose Changes in Background HCM Therapy From Baseline Through Week 56

eTable 7. Safety End Points and Adverse Events Through Week 56

eTable 8. Correlation Between Mean (± SD) Site-Read and Core-Lab Read Echocardiographic Measurements (Obtained Between Weeks 32-56)

eAppendix 2.

eFigure 1. Dose Titration Scheme for VALOR-HCM Trial

eFigure 2. Change in Biomarker and Echocardiographic Parameters From Baseline to Week 56 for the Original Mavacamten and the Placebo Cross-Over Groups

eFigure 3. Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction at Various Time Points (Baseline to Week 56) in the Original Mavacamten and Placebo Cross-Over Groups

eFigure 4. Correlation Between Site-Read and Core Laboratory Echocardiographic LVEF Measurements

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Maron BJ, Gardin JM, Flack JM, Gidding SS, Kurosaki TT, Bild DE. Prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a general population of young adults: echocardiographic analysis of 4111 subjects in the CARDIA study—Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults. Circulation. 1995;92(4):785-789. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.92.4.785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semsarian C, Ingles J, Maron MS, Maron BJ. New perspectives on the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(12):1249-1254. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, et al. ; Authors/Task Force members . 2014 ESC Guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the task force for the diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2014;35(39):2733-2779. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ommen SR, Mital S, Burke MA, et al. 2020 AHA/ACC guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(25):e159-e240. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maron BJ, Desai MY, Nishimura RA, et al. Management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(4):390-414. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ommen SR, Maron BJ, Olivotto I, et al. Long-term effects of surgical septal myectomy on survival in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(3):470-476. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smedira NG, Lytle BW, Lever HM, et al. Current effectiveness and risks of isolated septal myectomy for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85(1):127-133. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.07.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woo A, Williams WG, Choi R, et al. Clinical and echocardiographic determinants of long-term survival after surgical myectomy in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2005;111(16):2033-2041. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000162460.36735.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ball W, Ivanov J, Rakowski H, et al. Long-term survival in patients with resting obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy comparison of conservative versus invasive treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(22):2313-2321. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desai MY, Bhonsale A, Smedira NG, et al. Predictors of long-term outcomes in symptomatic hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy patients undergoing surgical relief of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Circulation. 2013;128(3):209-216. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alashi A, Smedira NG, Hodges K, et al. Outcomes in guideline-based class I indication vs earlier referral for surgical myectomy in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(1):e016210. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen A, Schaff HV, Ommen SR, et al. Late health status of patients undergoing myectomy for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;111(6):1867-1875. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desai MY, Tower-Rader A, Szpakowski N, Mentias A, Popovic ZB, Smedira NG. Association of septal myectomy with quality of life in patients with left ventricular outflow tract obstruction from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e227293. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.7293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veselka J, Krejčí J, Tomašov P, Zemánek D. Long-term survival after alcohol septal ablation for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: a comparison with general population. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(30):2040-2045. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veselka J, Lawrenz T, Stellbrink C, et al. Early outcomes of alcohol septal ablation for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: a European multicenter and multinational study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;84(1):101-107. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorajja P, Ommen SR, Holmes DR Jr, et al. Survival after alcohol septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2012;126(20):2374-2380. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.076257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stern JA, Markova S, Ueda Y, et al. A small molecule inhibitor of sarcomere contractility acutely relieves left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0168407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olivotto I, Oreziak A, Barriales-Villa R, et al. ; EXPLORER-HCM study investigators . Mavacamten for treatment of symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (EXPLORER-HCM): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10253):759-769. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31792-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heitner SB, Jacoby D, Lester SJ, et al. Mavacamten treatment for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(11):741-748. doi: 10.7326/M18-3016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desai MY, Owens A, Geske JB, et al. Myosin inhibition in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy referred for septal reduction therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(2):95-108. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.04.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desai MY, Owens A, Geske JB, et al. Dose-blinded myosin inhibition in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy referred for septal reduction therapy: outcomes through 32 weeks. Circulation. 2023;147(11):850-863. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.062534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desai MY, Wolski K, Owens A, et al. Study design and rationale of VALOR-HCM: evaluation of mavacamten in adults with symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy who are eligible for septal reduction therapy. Am Heart J. 2021;239:80-89. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2021.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gersh BJ, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, et al. ; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines . 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines—developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(25):e212-e260. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cremer PC, Geske JB, Owens A, et al. Myosin inhibition and left ventricular diastolic function in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy referred for septal reduction therapy: insights from the VALOR-HCM Study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15(12):e014986. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.122.014986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maron BJ, Desai MY, Nishimura RA, et al. Diagnosis and evaluation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(4):372-389. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sherrid MV. Drug therapy for hypertrophic cardiomypathy: physiology and practice. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2016;12(1):52-65. doi: 10.2174/1573403X1201160126125403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dybro AM, Rasmussen TB, Nielsen RR, et al. Effects of metoprolol on exercise hemodynamics in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(16):1565-1575. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol.

eAppendix 1.

eTable 1. Key Baseline Patient Characteristics, Separated by Sex

eTable 2. Final Dosing Chart for the Study in Both Groups

eTable 3. Select End Points for 40 and 56 Weeks of Exposure to Mavacamten, Separated by Sex

eTable 4. Data on Patients Proceeding to SRT

eTable 5. Week 56 Data on Eligible Patients Who Did Not Choose to Undergo SRT

eTable 6. Dose Changes in Background HCM Therapy From Baseline Through Week 56

eTable 7. Safety End Points and Adverse Events Through Week 56

eTable 8. Correlation Between Mean (± SD) Site-Read and Core-Lab Read Echocardiographic Measurements (Obtained Between Weeks 32-56)

eAppendix 2.

eFigure 1. Dose Titration Scheme for VALOR-HCM Trial

eFigure 2. Change in Biomarker and Echocardiographic Parameters From Baseline to Week 56 for the Original Mavacamten and the Placebo Cross-Over Groups

eFigure 3. Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction at Various Time Points (Baseline to Week 56) in the Original Mavacamten and Placebo Cross-Over Groups

eFigure 4. Correlation Between Site-Read and Core Laboratory Echocardiographic LVEF Measurements

Data Sharing Statement