Abstract

Twenty-four isolates of Actinobacillus seminis were typed by PCR ribotyping, repetitive extragenic palindromic element (REP)-based PCR, and enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC)-based PCR. Five types were distinguished by REP-PCR, and nine types were distinguished by ERIC-PCR. PCR ribotyping produced the simplest pattern and could be useful for identification of A. seminis and for its differentiation from related species. REP- and ERIC-PCR could be used for strain differentiation in epidemiological studies of A. seminis.

Actinobacillus seminis is a common cause of ovine epididymitis and ram infertility throughout the world (2, 6, 10, 21). It was first isolated in the United Kingdom in 1991 (7) and in one survey was found to be present in the semen of 19% of infertile rams (11). Clinical infections are usually unresponsive to treatment, and because infected animals are of considerable financial value, economic losses can be considerable. A. seminis is a fastidious, slow-growing, pleomorphic, weakly fermentative bacterium. Primary isolation and presumptive identification take several days; there are relatively few distinguishing tests for this and phenotypically similar organisms such as Histophilus ovis, which is also associated with epididymitis; and there have been cases of misidentification (20). It has been proposed that gram-negative pleomorphic bacteria which are catalase, oxidase, nitrate, and ornithine decarboxylase positive and indole, urease, phosphatase, and β-galactosidase negative should be considered A. seminis (6), and the API-ZYM system has been shown to be useful for provisional identification (4). However, because identification is laborious and because there is no published phenotypic or genotypic method for intraspecies discrimination of A. seminis isolates, knowledge of the mechanisms of transmission and persistence in rams and ewes and of the pathogenic potential of different isolates is uncertain. In a previous study, a combination of PCR ribotyping, repetitive extragenic palindromic element (REP)-based PCR, and enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC)-based PCR techniques was used for identification and fingerprinting of Haemophilus somnus isolates of ovine and bovine origin (1). These methods were also found to be applicable to the characterization of A. seminis strains.

Bacterial isolates.

Twenty-four A. seminis isolates were included in this study (Table 1). The type strain of A. seminis, NCTC 10851, was obtained from the National Collection of Type Cultures, Colindale, United Kingdom. All other field strains were isolated in Scottish Agricultural College Veterinary Services Laboratories, except for SA32 and SA33, which were kindly provided by P. J. Heath (7), and strain X16, which was isolated by one of the authors (S. Appuhamy) from the reproductive tract of a cow from slaughterhouse materials. H. ovis strains were isolated by Scottish Agricultural College Veterinary Services. All isolates were stored at −80°C in brain heart infusion broth (Oxoid) supplemented with 10% glycerol, 1% Tris (BDH), 1% soluble starch (BDH), 0.5% sodium-l-aspartate (Sigma) and 0.001% thiamine monophosphate (Sigma), pH 7.8 (1). They were propagated on brain heart infusion agar (Oxoid) containing 5% sheep blood and 0.5% yeast extract (Oxoid), and plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h in a candle jar. The identity of A. seminis isolates was confirmed by a panel of cultural and biochemical tests (17) and by the API-ZYM system (BioMerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) (4, 11). All A. seminis isolates showed strong positive reactions in tests for leucine arylamidase, acid phosphatase, and β-glucuronidase. Variable intensities for the reaction of alkaline phosphatase were observed, and the bovine isolate X16 was negative for this reaction. Only one isolate (SA35) showed a weak positive reaction for lipase esterase. All other tests were negative.

TABLE 1.

Origins of A. seminis isolates and results of molecular typing

| Isolatea | Date of isolation (day/mo/yr) | Geographic origin | Breed of ram | Disease status | Ribotype | REP type | ERIC type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA39 | 27/01/93 | S. Scotland | Suffolk | Normal | a | 1 | A |

| NCTC 10851b | 1958 | Australia | No record | Epididymitis | a | 1 | B |

| SA31 | 04/12/95 | N. Scotland | Suffolk | Subfertile | a | 1 | C |

| SA36 | 25/11/92 | S. Scotland | Scottish Blackface | Normal | a | 1 | C |

| SA67 | 27/08/96 | N. Scotland | Border Leicester | Normal | a | 1 | C |

| SA71 | 28/11/96 | No record | No record | Normal | a | 1 | C |

| SA25 | 08/11/95 | No record | No record | No record | a | 1 | F |

| SA32 | Aug. 1989 | England | Suffolk | Epididymitis | a | 1 | G |

| SA65‡ | 08/03/96 | N. Scotland | Suffolk | Normal | a | 2 | B |

| SA66‡ | 15/03/96 | N. Scotland | Suffolk | Normal | a | 2 | B |

| SA37 | 26/11/92 | S. Scotland | Suffolk | Epididymitis | a | 3 | B |

| SA60 | 18/11/94 | S. Scotland | Suffolk | Epididymitis | a | 3 | B |

| SA70 | 11/09/96 | N. Scotland | Border Leicester | Epididymitis | a | 3 | D |

| SA43 | 28/07/95 | S. Scotland | Texel | Epididymitis | a | 3 | E |

| SA63 | 23/08/95 | England | Berrichon de Cher | Normal | a | 3 | H |

| SA30* | 27/11/95 | S. Scotland | Suffolk | Normal | a | 4 | E |

| SA64* | 09/01/96 | S. Scotland | Suffolk | Normal | a | 4 | E |

| SA34† | 02/10/92 | S. Scotland | Suffolk | Epididymitis | a | 4 | E |

| SA38† | 26/11/92 | S. Scotland | Suffolk | Epididymitis | a | 4 | E |

| SA35 | 06/10/92 | S. Scotland | Texel | Normal | a | 4 | E |

| SA61 | 07/12/94 | S. Scotland | Texel | Epididymitis | a | 4 | E |

| SA62 | 25/07/95 | S. Scotland | Poll Dorset | Normal | a | 4 | E |

| X16 | 25/07/95 | (Bovine) | Culled | a | 5 | I | |

| SA33 | Oct. 1990 | England | Poll Dorset | Epididymitis | b | 3 | E |

Strains marked with the same symbol (∗, †, or ‡) were isolated from samples taken at different times from the same animal.

Type strain.

PCR amplification.

Bacteria were suspended in 1-ml volumes of sterile distilled water to a turbidity equivalent to McFarland no. 5 standard (BioMerieux), heated to 100°C for 20 min, and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min; the supernatant was used as the source of template DNA for PCR. The primers were GIRRN (GAAGTCGTAACAAGG) and LIRRN (CAAGGCATCCACCGT) for PCR ribotyping (8), REP-IRDT (IIINCGNCGNCATCNGGC) and REP2-DT (NCGNCTTATCNGGCCTAC) for REP-PCR (18), and ERIC-IR (ATGTAAGCTCCTGGGGATTCAC) and ERIC-2 (AAGTAAGTGACTGGGGTGAGCG) for ERIC-PCR (18). They were obtained from Life Technologies Ltd. (Paisley, United Kingdom). PCR methods were optimized for template, deoxynucleoside triphosphate, primer, and magnesium ion concentrations by a modified Taguchi method based on the use of orthogonal arrays as described by Cobb and Clarkson (3). Annealing temperature and extension time were also optimized. High intensity, resolution, and sharpness of bands with a low background in an agarose gel were used as the criteria for optimization. The optimized reaction mixture (25 μl) contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 50 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Boehringer Mannheim, Lewes, United Kingdom), 100 pM each primer, 0.625 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Life Technologies Ltd.), and 2.5 μl of template DNA preparation. Twenty-five microliters of liquid paraffin was used to overlay each reaction mixture. Amplification was performed in a thermocycler (Techne Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom) for 35 cycles, consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 6 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 6 min. The amplified products were electrophoresed in 2.0% agarose type II-A (Sigma) in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer containing 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide/ml (15) in a horizontal submarine electrophoresis apparatus (E-C Apparatus Corporation, St. Petersburg, Fla.). The amplimers were visualized and photographed under UV light. Whenever a distinct PCR profile, in terms of the number and positions of the clearly visible bands, was observed, the corresponding strain was given a unique number or letter designation.

Typing of strains.

REP-PCR, ERIC-PCR, and PCR ribotyping have been used to identify species and also to differentiate strains within species of both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (1, 8, 9, 18). Boiled cell extracts as the source of template DNA produced the same results as extracted chromosomal DNA for all three PCR methods (1, 9). PCR-based fingerprinting is therefore simple and rapid and can be performed with very small quantities of bacterial cultures. Reproducibility was good for all three methods not only with the same template, but also with template samples derived from different cultures, although some day-to-day variation in the intensity of amplimers, particularly of the minor bands, was observed.

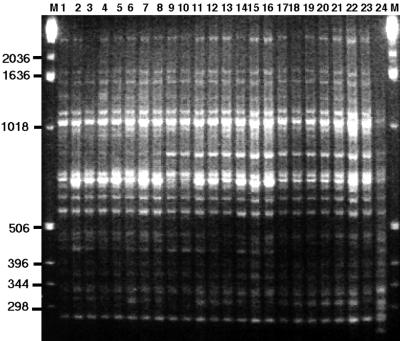

With the REP-PCR method, profiles of A. seminis revealed amplified bands ranging from <0.25 to 2.5 kb with various intensities (Fig. 1). This method produced complex banding patterns, but the 24 isolates were grouped into five distinct patterns of fingerprints, each of which was assigned a number (Table 1). Group 1 included the type strain and seven other isolates with similar patterns, and this was the largest group. Group 2 had two isolates, group 3 had six isolates, and group 4 had seven isolates. The bovine strain (X16) had a unique pattern. There were major REP markers of 275, 550, 600, 800, 1,050, and 1,100 bp common to all A. seminis isolates.

FIG. 1.

Fingerprints obtained by REP-PCR for A. seminis isolates. Lanes M, 1-kb DNA ladder; lanes 1 to 24, A. seminis isolates NCTC 10851 (type strain), SA25, SA31, SA32, SA36, SA39, SA67, SA71, SA65, SA66, SA33, SA37, SA43, SA60, SA63, SA70, SA30, SA34, SA35, SA38, SA61, SA62, SA64, and X16, respectively. The profiles have been arranged so that isolates of a similar type are grouped together: type 1 in lanes 1 to 8, type 2 in lanes 9 to 10, type 3 in lanes 11 to 16, type 4 in lanes 17 to 23, and type 5 in lane 24 (see Table 1).

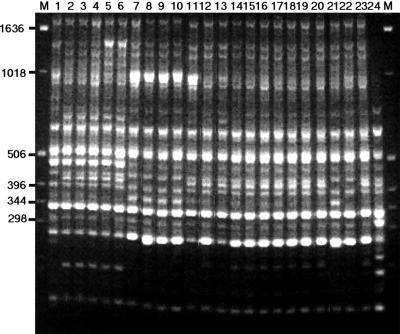

ERIC-PCR produced nine distinguishable patterns for the 24 isolates and, therefore, the highest degree of discrimination among isolates (Table 1). The fragments ranged from <0.1 to 1.65 kb, with various band intensities (Fig. 2). The distribution of isolates was as follows: group B, five isolates, including the type strain; group C, four isolates; and group E, nine isolates. Groups A, D, F, G, H, and I contained one isolate each. ERIC-PCR fingerprints of all isolates showed common markers, with the bands at 330, 515, and 600 bp being the most intense. However, the bovine isolate, X16, was clearly distinguishable from all the other strains.

FIG. 2.

Fingerprints obtained by ERIC-PCR for A. seminis isolates. Lanes M, 1-kb DNA ladder; lanes 1 to 24, A. seminis isolates SA39, NCTC 10851 (type strain), SA37, SA60, SA65, SA66, SA31, SA36, SA67, SA71, SA70, SA30, SA33, SA34, SA35, SA38, SA43, SA61, SA62, SA64, SA25, SA32, SA63, and X16, respectively. The profiles have been arranged so that isolates of a similar type are grouped together: type A in lane 1, type B in lanes 2 to 6, type C in lanes 7 to 10, type D in lane 11, type E in lanes 12 to 20, type F in lane 21, type G in lane 22, type H in lane 23, and type I in lane 24 (see Table 1).

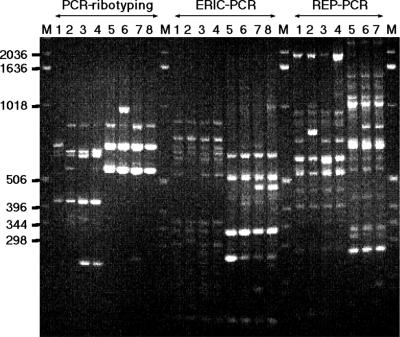

PCR ribotyping of the 24 isolates gave very similar fingerprints for all isolates except SA33. The profiles were characterized by two high-intensity bands of 0.55 and 0.7 kb and a less-intense band of 0.85 kb (Fig. 3). Isolate SA33 showed an additional intense band of 0.9 kb, and for this reason, this isolate was considered to be a separate type by PCR ribotyping (Table 1). The isolate of bovine origin (X16) showed the same band pattern as the ovine isolates.

FIG. 3.

Differentiation of A. seminis from H. ovis by PCR methods. Lanes M, 1-kb DNA ladder; lanes 1 to 4, different isolates of H. ovis; lanes 5 to 8, A. seminis strains SA32, SA33, SA37, and SA39, respectively.

The types generated by the PCR methods showed no correlation with the breed of sheep or disease condition of the host (Table 1). However, several of the isolates from southern Scotland obtained over a 3- to 4-year period possessed similar fingerprints, but the number of isolates examined was not sufficient to draw clear conclusions. However, one significant finding was that isolates taken from the same animal at different times showed the same fingerprint by all three methods (SA65 and SA66, SA30 and SA64, and SA34 and SA38; see Table 1).

The bovine strain (X16) was isolated from the vestibular opening of a cow during a study of H. somnus isolates collected from slaughterhouse materials. This isolate was culturally indistinguishable from H. somnus but was catalase positive. There have been previous reports of A. seminis being isolated from cattle, but those isolates were catalase negative (5). Because A. seminis is usually described as a catalase-positive organism (6, 16), the identity of the previous isolates from cattle is uncertain. Isolate X16 was confirmed as an A. seminis isolate by API-ZYM. Its REP and ERIC fingerprints showed common markers with other A. seminis isolates, and it gave a PCR ribotyping pattern characteristic of A. seminis. These findings suggest that this isolate may well represent a subtype of A. seminis of bovine origin.

Comparison with H. ovis.

H. ovis is an ovine pathogen that can cause epididymitis and orchitis. It may well be present in the same clinical specimens as A. seminis, and it may be difficult to distinguish biochemically between the two species. Stephens et al. (17) distinguished two isolates of A. seminis from the Haemophilus-Histophilus group by their lack of yellow pigment, production of catalase, and differences in cell wall envelope protein profiles. Recent genetic studies have shown a clearer picture of species differentiation, for example, by restriction endonuclease profiles for BamHI (12, 13) and DNA-DNA hybridization techniques (14, 19). In 1990, Sneath and Stevens (16) defined the properties of A. seminis and proposed it as a new species on the basis of cultural, biochemical, and DNA-DNA hybridization methods. When a number of representative H. ovis isolates were compared with A. seminis strains by the three PCR methods, the profiles were completely different (Fig. 3). The profiles were also distinct from those of H. somnus isolates examined previously (1) (data not shown). Thus, the PCR methods can readily be used to differentiate between A. seminis and the Haemophilus-Histophilus group.

In conclusion, PCR ribotyping, REP-PCR, and ERIC-PCR generated reproducible and discriminatory fingerprints of A. seminis, and the genetic heterogeneity of this species was revealed. In a previous report, A. seminis was found to be genetically homogeneous by BamHI restriction endonuclease profiles (12). Among our 24 isolates there were two ribotypes, five REP types, and nine ERIC types (Table 1). PCR ribotyping produced a simple pattern which could be used to identify A. seminis and to differentiate it from other, related species. REP and ERIC-PCR produced complex patterns but showed common markers for all isolates. This indicates that these two methods could be used for strain differentiation of A. seminis for epidemiological studies and also for confirmation of the identity of A. seminis isolates by the presence of these common markers. ERIC-PCR was more discriminatory than REP-PCR.

Acknowledgments

S.A. was supported by an Agricultural Research Scholarship from the Government of Sri Lanka and a scholarship provided by the Institute of Biomedical and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow.

The useful comments of D. J. Taylor, Department of Veterinary Pathology, University of Glasgow, and the kind cooperation of M. J. A. Mylne, Veterinary Officer in Charge, Edinburgh Genetics, Bush Estate, Penicuik, Scotland, are gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appuhamy S, Parton R, Coote J G, Gibbs H A. Genomic fingerprinting of Haemophilus somnus by a combination of PCR methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:288–291. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.288-291.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baynes I D, Simmons G C. Ovine epididymitis caused by Actinobacillus seminis, N. sp. Aust Vet J. 1960;36:454–459. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cobb B D, Clarkson J M. A simple procedure for optimising the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using modified Taguchi methods. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3801–3805. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.18.3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cousins D V, Lloyd J M. Rapid identification of Hemophilus somnus, Histophilus ovis and Actinobacillus seminis using the API-ZYM system. Vet Microbiol. 1988;17:75–81. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(88)90081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon R J, Stevenson B J, Sims K R. Actinobacillus seminis isolated from cattle. N Z Vet J. 1983;31:122–123. doi: 10.1080/00480169.1983.34992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hajtos I, Fodor L, Glavits R, Varga J. Isolation and characterization of Actinobacillus seminis strains from ovine semen samples and epididymitis. J Vet Med Ser B. 1987;34:138–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1987.tb00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heath P J, Davies I H, Morgan J H, Aitken I A. Isolation of Actinobacillus seminis from rams in the United Kingdom. Vet Rec. 1991;129:304–307. doi: 10.1136/vr.129.14.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen M A, Webster J A, Straus N. Rapid identification of bacteria on the basis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified ribosomal DNA spacer polymorphisms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:945–952. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.945-952.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerr K G. The rap on REP-PCR-based typing systems. Rev Med Microbiol. 1994;5:233–244. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Livingston C W, Hardy W T. Isolation of Actinobacillus seminis from ovine epididymitis. Am J Vet Res. 1964;25:660–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Low J C, Somerville D, Mylne M J A, McKelvey W A C. Prevalence of Actinobacillus seminis in the semen of rams in the United Kingdom. Vet Rec. 1995;136:268–269. doi: 10.1136/vr.136.11.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGillivery D J, Webber J J. Genetic homogeneity of Actinobacillus seminis isolates. Res Vet Sci. 1989;46:424–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGillivery D J, Webber J J, Dean H F. Characterization of Histophilus ovis and related organisms by restriction endonuclease analysis. Aust Vet J. 1986;63:389–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piechulla K, Mutters R, Burbach S, Klussmeier R, Pohl S, Mannheim W. Deoxyribonucleic acid relationships of “Histophilus ovis/Haemophilus somnus,” Haemophilus haemoglobinophilus, and “Actinobacillus seminis.”. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1986;36:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sneath P H A, Stevens M. Actinobacillus rossii sp. nov., Actinobacillus seminis sp. nov., nom. rev., Pasteurella bettii sp. nov., Pasteurella lymphangitidis sp. nov., Pasteurella mairi sp. nov., and Pasteurella trehalosi sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1990;40:148–153. doi: 10.1099/00207713-40-2-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephens L R, Humphrey J D, Little P B, Barnum D A. Morphological, biochemical, antigenic, and cytochemical relationships among Haemophilus somnus, Haemophilus agni, Haemophilus haemoglobinophilus, Histophilus ovis, and Actinobacillus seminis. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;17:728–737. doi: 10.1128/jcm.17.5.728-737.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Versalovic J, Koeuth T, Lupski J R. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6823–6831. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.24.6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker R L, Biberstein E L, Pritchett R F, Kirkham C. Deoxyribonucleic acid relatedness among Haemophilus somnus, Haemophilus agni, Histophilus ovis, Actinobacillus seminis, and Haemophilus influenzae. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1985;35:46–49. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker R L, Leamaster B R, Stellflug J N, Biberstein E L. Association of age of ram with distribution of epididymal lesions and etiologic agent. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1986;188:393–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Worthington R W, Bosman P P. Isolation of Actinobacillus seminis in South Africa. J S Afr Vet Med Assoc. 1968;39:81–85. [Google Scholar]