ABSTRACT

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen heavily implicated in chronic diseases. Immunocompromised patients that become infected with P. aeruginosa usually are afflicted with a lifelong chronic infection, leading to worsened patient outcomes. The complement system is an integral piece of the first line of defense against invading microorganisms. Gram-negative bacteria are thought to be generally susceptible to attack from complement; however, P. aeruginosa can be an exception, with certain strains being serum resistant. Various molecular mechanisms have been described that confer P. aeruginosa unique resistance to numerous aspects of the complement response. In this review, we summarize the current published literature regarding the interactions of P. aeruginosa and complement, as well as the mechanisms used by P. aeruginosa to exploit various complement deficiencies and the strategies used to disrupt or hijack normal complement activities.

KEYWORDS: complement, innate immunity, opsonization, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, biofilms, immune evasion, persister cells, phagocytosis

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a clinically significant Gram-negative opportunistic pathogen, is implicated in several conditions/diseases, many of which are prolonged and worsened by chronic infections, including nosocomial pneumonia, bacteremia, burn wound infections, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis, endotoxin shock, and lung infections in cystic fibrosis (CF) (1–7). To progress from an acute to a chronic infection, bacteria must survive several components of the host immunity. P. aeruginosa can evade the host immune response in a multitude of ways. It is becoming increasingly evident that evasion and modulation of the host complement system by P. aeruginosa is critical in surviving host defenses and sustaining chronic infection.

COMPLEMENT SYSTEM

The host innate immune system nonspecifically recognizes and eliminates pathogens. Toll-like receptors on circulating phagocytic immune cells, primarily macrophages and neutrophils, bind to sites on pathogens known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), triggering an intracellular signaling cascade, resulting in proinflammatory cytokine production and phagocyte activation (8). The secretion of these cytokines subsequently triggers the inflammatory response, and the recruitment of more phagocytic cells to the area to eliminate the immediate pathogenic threat (9). Another avenue of recognition of pathogens by phagocytes is known as opsonization, where a molecule that the phagocytes can recognize, first binds to the pathogen and is then recognized by the immune cells directly, leading to increased engulfment of the pathogens (10). Pathogens can be bound and opsonized by antibodies or by certain proteins of the complement cascade (10).

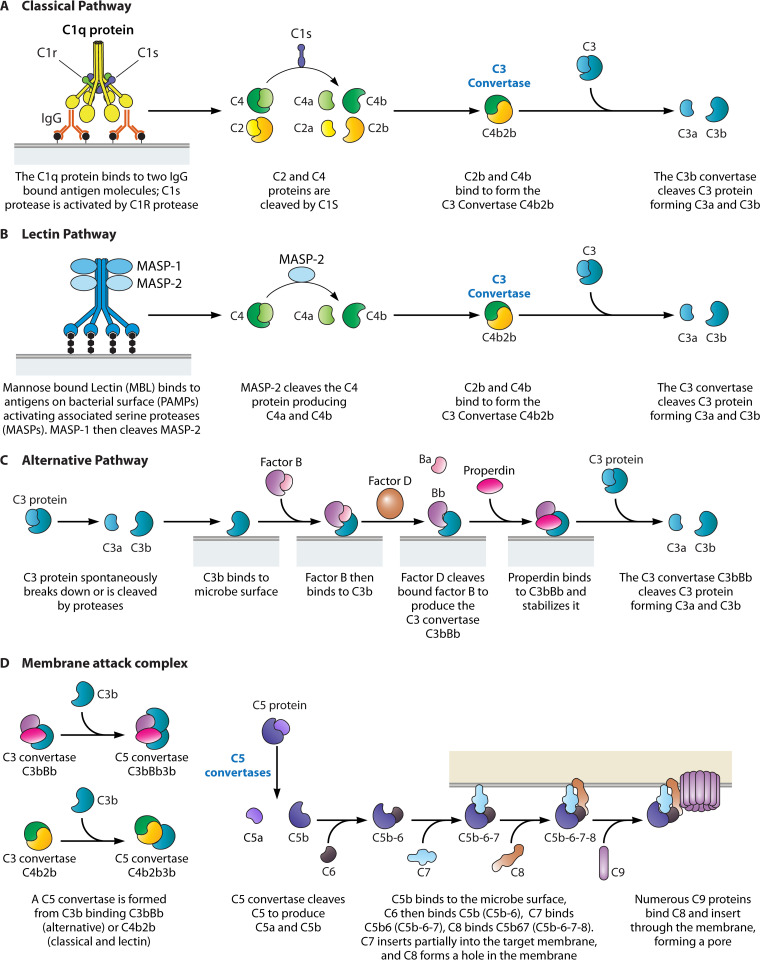

The complement system is a crucial component of host innate immunity, which ultimately results in rapid bacterial detection, direct bacterial elimination, and recruitment of circulating leukocytes to the site of infection. The complement system consists of three main pathways: the classical, the alternative, and the lectin. Activation of any of these pathways results in the generation of C3 and C5 convertases (11). The C3 convertases effectuate the cleavage of C3 and the subsequent deposition of complement protein C3b on foreign bodies, while C5 convertases cleave C5 and initiate the formation of the membrane attack complex (11) (Table 1). The overarching complement system is associated with the host blood, providing the main mechanism for bactericidal activities in host serum.

TABLE 1.

Proteins and enzymes involved in the initial activation of the three complement pathways

| Complement pathways | Initial activation | Protein cleavage | C3b convertase | C5 convertase | Anaphylatoxins | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical | C1q antibody binds two antigen-bound IgG molecules | C2 and C4 cleaved by the C1s protease | C4b2a | C4b2a3b | C2b and C4a | 12 – 16 |

| Lectin | Mannose-bound lectin (MBL) binds bacterial surface | MASP-2 cleaves C4 | C4b2a | C3b2a3b | C4a | 17 |

| Alternative | C3b binds to a microbial surface | C3 is spontaneously cleaved in the blood | C3bBb | C3bBb3b | C3a | 15, 17–19 |

The classical pathway (Fig. 1A) is initiated when C1qr2s2 binds to the Fc region of IgM or IgG antibody subclasses IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, upon their binding to an antigen and forming immune complexes (ICs) (12, 13). This results in the cleavage of C2 and C4 by the serine protease C1s (12, 13). C1s is activated when cleaved by the serine protease C1r, found within the same C1qr2s2 and IC complex. The resulting C4b and C2a combine to form the C3 convertase C4b2b (previously C4b2a) (14–16). The smaller fragments, C2a and C4a, act as mediators of inflammation and diffuse away (18). C3 convertases act to cleave C3 into C3a and C3b, the latter being critical in opsonization and formation of C5 convertases C4b2b3b (in the classical and lectin pathways) and C3bBb3b (from the alternative pathway), each of which function to cleave C5 into C5a (diffuses away) and C5b which binds to C6 and begins the terminal sequence of the complement pathway (15, 20). Both C3a and C5a are classified as anaphylatoxins which diffuse away from the site of the complement cascade and act as mediators of inflammation (15, 17, 19). C3b and C4b (to a lesser extent) act as opsonins by binding their exposed thioester groups to target foreign objects, including membranes of pathogens (18). Receptors expressed on phagocytes, namely CR1 and CR3, respectively, recognize the opsonins C3b and C4b, and iC3b, a further cleaved form of C3b (18).

FIG 1.

Summary of the complement system. The three pathways of the complement system: (A) classical, (B) lectin, and (C) alternative. All of which culminate in the formation of a (D) membrane attack complex (MAC).

The lectin pathway (Fig. 1B) is activated when mannose-binding lectin (MBL), collectin-11, or ficolin complexes bind to PAMPs. This binding activates MBL-associated serine proteases (MASPs), which are structurally similar to the C1qr2s2 complex of the classical pathway, then MASPs cleave the C4 protein, providing an antibody-independent means of cleaving and activating C4, resulting in the formation of C3 convertase C4b2a, ultimately leading to the terminal sequence of the complement pathway (21, 22).

The alternative pathway (Fig. 1C) is also an antibody-independent means to generate membrane-bound C5b leading to the terminal sequence of the complement pathway. It is initiated when C3b binds to foreign surfaces, such as but not limited to, lipopolysaccharide of Gram-negative bacteria, teichoic acid of Gram-positive bacteria, and fungal cell walls (21). Once initiated, the C3 convertase C3bBb is formed when C3b-bound Factor B is fragmented into Ba and Bb by the serine protease Factor D. Fragment C3bBa diffuses, while the newly formed complex C3bBb is stabilized by binding of properdin and then acts as a C3 convertase (23). Increase of C3b from the activity of the C3 convertase results in higher number of C3b fragments available to bind the surface of pathogens and to reinitiate the alternative pathway resulting in an amplification loop (18).

The membrane attack complex (MAC) is initiated when the C3b fragments are formed. This is initiated independently of the complement pathway that was initially activated. C3b binds to the C3bBb complex to form the C5 convertase C3bBb3b to initiate the formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC), the terminal sequence of the complement system (Fig. 1D). Upon C5b binding to C6, the C5b6 complex binds C7 and inserts partially into the phospholipid bilayer of the target (24). C8 then binds and forms a small hole in the membrane, where through polymerization and binding of C9, the hole expands, and the target cell undergoes lysis as it loses its ability to maintain osmotic stability (24).

The overarching complement system is complex, and bacteria have evolved several strategies to subvert or appropriate many aspects of the system to ensure their survival.

P. AERUGINOSA STRATEGIES TO UNDERMINE AND EVADE COMPLEMENT AND INNATE IMMUNITY

The CF lung.

Patients with CF, a disease where there is an impairment of the CFTR (a chloride channel) due to one or more gene mutations, have a decreased volume of periciliary fluid, resulting in a decreased ability to clear inhaled pathogens and lung infections (25). One of the primary pathogens associated with lung infection in CF and decreased patient survival is P. aeruginosa (26). Lung disease progression in CF due to P. aeruginosa is initiated by the inhalation of a nonmucoid P. aeruginosa that, upon infection of the airway, can sometimes switch to a mucoid phenotype, expressing alginate as an exopolysaccharide (EPS), which encases the bacteria in an aggregative biofilm mode of growth (27–29). Bacteria within these biofilms are recalcitrant to treatment by antibiotics (30) and nonopsonic phagocytosis from host immune cells (31). This recalcitrance to treatment by antibiotics occurs partially due to alginate present within the EPS that bind essential nutrients, causing the bacteria to have a slower metabolic rate, diminishing the effect of the antibiotic (30). Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are crucial for the structure and defense of Gram-negative bacteria. P. aeruginosa LPS is composed of lipid A, oligosaccharide, and O antigen (32). The O antigen has been extensively implicated in bacterial defense from the host and consists of A-band and B-band (32). The A-band is a homopolymer of d-rhamnose, while the B-band is a heteropolymer and is responsible for serogroup specificity (32). Lipid A is the hydrophobic portion and anchors the LPS to the outer membrane (33). The O antigen is a long polysaccharide which is synthesized separately from lipid A and attached later. Thus, not every lipid A molecule has an attached O antigen. LPS with O antigen are considered capped and the outer membrane is heterogenous, consisting of capped and uncapped LPS molecules (33). Bacteria with long O antigen tails are more resistant to complement killing than isogenic mutants with O antigen deficiency (33). Potential factors for this include inefficient convertase formation due to blocked C3b binding sites and activation of the membrane attack complex far from the bacterial membrane (33). In the lung of CF patients, O antigen subunits are used to glycosylate pilin and this modification provides resistance to opsonizing lectins that target LPS (33). The length of the B-band O antigen side chains is regulated by Wzz proteins by determining how many subunits are combined (34). Disruption of Wzz-related genes has been shown to decrease virulence and, in some cases, lower survival in serum, illustrating that Wzz proteins directly affect the ability of P. aeruginosa to survive serum treatment (35). These results support early work that demonstrated that P. aeruginosa strains with lengthened O antigen side chains are typically resistant to complement attack in serum (36) due to failure of the MAC to securely insert into the outer membrane (37). Changes in LPS structure mediated by WarA (a cyclic-di-GMP associated methyltransferase) enable P. aeruginosa to remain undetected by neutrophils (38). It is unknown whether this is due to a lack of complement deposition on the bacteria through modification of LPS, but it is plausible that modification of LPS is responsible for prevention of C3b deposition, therefore preventing opsonization and engulfment by neutrophils (33, 38). Furthermore, in the presence of host-derived itaconate, clinical strains of P. aeruginosa isolated from soft tissues and CF sputum redirect their metabolism toward biofilm formation (39). This metabolism redirection results in a decrease in expression of LPS-related genes, including the one coding for LptD, the outer membrane protein that translocates LPS to the bacterial surface leading to an accumulation of LPS in the periplasmic space (39). The change in metabolism also results in an increase of EPS by upregulating algT and other related genes (39). Interestingly, mucoid P. aeruginosa express little to no O antigen (40) and are susceptible to serum treatment (41). This further supports that when growing in the CF lung, P. aeruginosa is thought to be primarily in a biofilm mode of growth (42–44) and is resilient to host complement.

Altogether, P. aeruginosa employs several strategies to survive complement attack in the CF lung. The overexpression of alginate and the subsequent biofilm mode of growth results in an increase of EPS, rendering the encased bacteria physically protected from complement binding. Alternatively, P. aeruginosa not associated in biofilms can also use LPS as a key structural feature of P. aeruginosa to evade complement. This is achieved by modulation of the length of the O antigen, which causes either premature activation of the MAC or blocked C3b binding, thus rendering protection against complement attack.

Persister cells.

When in biofilms, P. aeruginosa bacterial cells are encased in an extracellular matrix composed of EPS, proteins, exogenous DNA (eDNA), RNA, and host polymers (28, 45–47). Within the biofilms, bacteria are in several metabolic states, one being a subpopulation of metabolically dormant/low metabolic state, commonly named persister cells (47–49). Persister cells, a subset (0.0001% to 1%) of the regular vegetative bacterial cells, are known to be tolerant to antimicrobials and hypothesized to ensure the success of the bacterial population in times of stress (49). Persister cells have been described in every species of bacteria in which they have been sought after (50) and have previously been found to be engulfed by THP-1 macrophages significantly less compared to the regular vegetative cells (51, 52). In P. aeruginosa the reduced engulfment by macrophages occurs although the cells are opsonized by C3b (53). However, there is a reduction of C5b deposition on the viable persister cells’ membrane, which is possibly related with its recalcitrant death by complement in human serum/plasma. (48, 49). Interestingly, functional C5 convertase activity on C3b-opsonized P. aeruginosa during murine infections when using regular vegetative cells has been described, despite the overall serum resilient phenotype (54).

Biofilm matrix.

Often upon infection with P. aeruginosa, the hosts’ inflammatory response creates a hostile environment, and this can lead to the adaptation of P. aeruginosa (55). P. aeruginosa rugose small-colony variants that lack the methylesterase wspF (PAO1 ΔwspF) have been shown to overproduce c-di-GMP and some biofilm matrix components (55). These variants were shown to avoid engulfment by neutrophils, despite being opsonized by human serum (55). The exopolysaccharide Psl produced by P. aeruginosa PAO1 is involved in the interactions between biofilms and other surfaces (56). Psl has been demonstrated to inhibit opsonization of the bacterial surface in mucoid strains (57). Psl also decreases deposition of C3, C5, and C7, resulting in decreased opsonization and killing by phagocytes (58). Interestingly, when treated with monoclonal antibodies targeting Psl, complement was activated, and neutrophils had higher success recognizing the infection (59). Furthermore, P. aeruginosa expresses a serine-protease dubbed Ecotin, which binds to Psl and confers protection against neutrophil elastase in both biofilm-associated and planktonic P. aeruginosa (60). Ecotin has also been shown to inhibit MASP-1, MASP-2, and importantly MASP-3, the primary Factor D activator in human blood, thereby crippling the alternative pathway (61). In addition to Psl, O-acetylation of alginate which is expressed in mucoid CF-associated strains, also confers resistance to complement-mediated opsonization by inhibition of the alternative pathway, as well as inhibition of alginate-specific antibodies (62).

Overall, P. aeruginosa uses different growth and phenotypic strategies to avoid clearance by the complement system. A key phenotypic change P. aeruginosa uses is the modification of the O antigen of LPS, resulting in the insertion of less MACs into the bacterial surface. An antibiotic-tolerant, metabolically dormant subset of bacteria called persister cells have been demonstrated to be resistant to killing by complement, via the decrease of C5b and MAC deposition on the outer membrane. The biofilm mode of growth confers protection to serum and complement via the encasement of the bacteria in exopolysaccharides inhibiting opsonization. These effects are supplemented by expression of Ecotin protease, which binds to the exopolysaccharide Psl and protects P. aeruginosa from killing by neutrophils.

Preventing complement protein deposition on the cell by P. aeruginosa.

P. aeruginosa adapts to environmental changes by using two-component regulatory systems. One such system, the PhoP/PhoQ system, is responsive to Mg2+ concentration and acidic pH (63). In P. aeruginosa PAO1, under conditions of Mg2+ starvation, both PhoQ-deficient mutant and wild type (WT) bind similar levels of C3 protein; however, in the presence of Mg2+, the wild-type strain binds to significantly less C3 than the PhoQ-deficient mutant, indicating that PhoQ detects Mg2+ and indirectly suppresses C3 deposition (63). PhoQ also modulates OprH, an outer membrane protein, as when it detects Mg2+ it suppresses C3 deposition by decreasing oprH expression, which has been found to bind C3 and increase phagocytosis (63). Moreover, PhoQ deficiency has also been associated with a reduction of virulence in a chronic respiratory infection rat model (64).

A common strategy to avoid the effect of complement is the coating of the bacteria and eukaryotic parasites extracellular surfaces (65, 66). One such example is the uptake and binding of sialic acid by P. aeruginosa cells, which is positively correlated with prevention of C3 deposition (67). Sialic acids are a family of sugars primarily derived from N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) that naturally occur in mammals. Siglecs (sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin like lectins) are cell surface proteins found on immune cells and function by binding sialic acid, allowing host recognition of pathogens. When P. aeruginosa cells are bound to sialic acid, they also strongly bind to inhibitory siglec-9 and siglec-7, which are found on monocytes and natural killer cells, leading to decreased C3 deposition and possible immunosuppression due to the immune inhibitory features of siglecs (67, 68).

In P. aeruginosa (PAO1) OprF, a membrane protein structurally related to the complement binding OmpA in E. coli, has been identified as a C3b acceptor and as such, it is important for a bactericidal outcome (69). In E. coli, OmpA recruits the complement regulatory protein C4 binding protein (C4bp), preventing C4b2b convertase from forming and can accelerate the decay thereof (70). Thus, OprF in P. aeruginosa could have a similar function (70). Furthermore, the expression of OprF is crucial to P. aeruginosa immune subversion in ear infections (71).

In summary, the strategy of prevention of complement deposition is a powerful tool to prevent killing of P. aeruginosa by phagocytic cells. This is achieved through both indirect and direct means. Magnesium sensor PhoQ indirectly suppresses deposition of complement proteins through modulation of outer membrane proteins. Direct reduction of complement deposition is mediated by coating the surface of P. aeruginosa, with the coating of sialic acid described as a mechanism to avoid complement deposition.

Subversion of the complement system by P. aeruginosa proteins.

Pathogens also actively express their own proteins to subvert the complement system. AprA, a 50-kDa metalloprotease produced by P. aeruginosa, can degrade several complement proteins (72), decrease phagocytosis, and decrease C3b deposition via the lectin and classical pathways (72). AprA competitively cleaves C2, preventing its natural cleavage into C2a and C2b and, as such, the activation of the classical and lectin pathways (72). AprA can also prevent the formation of the chemotactic agent C5a, resulting in a similar outcome to the streptococcal C5a-peptidase, although the mechanism is one of prevention rather than degradation (72, 73). It has also been shown that AprA degrades monomeric flagellin, the ligand for toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5), enabling the bacteria to further evade the innate immune system (74).

Protease IV, a 26-kDa enzyme produced by P. aeruginosa, has been demonstrated to degrade complement proteins C1q and C3, as well as fibrinogen, plasminogen, immunoglobulin G, and some host defense molecules. Protease IV degrades the pulmonary surfactant proteins (SP) A, D, and B, impacting the innate host defense against inhaled pathogens within the lung (75, 76). Protease IV also has been shown to degrade complement-like proteins belonging to proteolytic cascade systems in insects (77). During infection of the human cornea, the P. aeruginosa small protease (PASP) can cleave collagens, resulting in the dysregulation of complement via protease IV activity and contributing to Pseudomonas keratitis (78).

Recently, the polysaccharide monooxygenase CbpD, was demonstrated to protect P. aeruginosa from MAC-mediated killing by preventing the complete assembly of the terminal sequence as evidenced by lower C9 detection (79). Infection with P. aeruginosa lacking CbpD led to an upregulation of the complement protein C4, apoptosis, and cell cycle host genes such as Irgm1 and Ywhang, suggesting that normal expression of CbpD tampers these effects down (80). This is significant because apoptosis is a commonly used strategy to clear the host of infection (79) and the complement system can be activated by cellular debris caused by apoptosis (81), particularly through direct binding of apoptotic cells by C1q (82) and MBL (83).

P. aeruginosa elastase, regulated by the quorum sensing las system, can destroy several complement proteins, including cell-bound C3 and fluid phase C9, and inactivate others, including fluid phase C2, C4, C6, and C7 (84). These findings were further confirmed when it was demonstrated that C1q and C3 were degraded by both elastase and alkaline protease derived from P. aeruginosa (85). In addition, P. aeruginosa isolated from skin ulcers can express elastase capable of destroying C3, degrading human wound fluid associated proteins, and inhibiting human fibroblast growth (86).

Overall, P. aeruginosa expresses several proteases, which either directly cleave complement proteins or cleave host proteins that allow for other protease activity. The P. aeruginosa proteases AprA, Protease IV, and elastase directly cleave or otherwise degrade several cell-bound or fluid phase complement proteins. The protease PASP is capable of degrading structural proteins in the eye, creating dysbiosis and allowing for increased protease IV activity. P. aeruginosa also produces another virulence factor, CbpD, which has been demonstrated to downregulate C4 and apoptosis genes, as well as confer resistance to MAC-mediated killing. The use of these proteases and virulence factors affords P. aeruginosa unique methods of survival against complement not necessarily present in other bacterial species.

DEFICIENCIES OF THE HOST

Lack of “normal” complement proteins can hinder host defenses and bolster P. aeruginosa survival. One of such proteins is C3, a critical component of the complement system. Organisms deficient in C3 lack the downstream fragmentary proteins, and therefore have a nonfunctional complement system, which can result in a lack of inflammation and immunity (87). Different outcomes were described for P. aeruginosa infection of C3- and C4-deficient mice challenged intranasally. C3-deficient mice were not able to clear P. aeruginosa lung infections, and as such, did not survive; however, C4 deficient mice survived similarly to controls (87). These findings indicate that the alternative pathway is imperative to immune protection to P. aeruginosa, as C4 is not involved in the alternative pathway (87). As previously noted, C3b can undergo proteolytic degradation into iC3b, which can no longer contribute to the production of anaphylatoxin C5a, or the membrane attack complex (88). Rapid conversion of deposited C3b into iC3b by serum-resistant strains have been reported (89). The lung proteome of CF patients shows lower levels of many complement proteins, possibly indicating a dysregulation in the complement system, hindering the host’s ability to respond to a chronic infection (90).

These findings also support the prevalence of P. aeruginosa in the lung of CF patients where a deficiency of the C3 protein significantly impacts host susceptibility to P. aeruginosa; however, this may not be the case in deficiency of the MASP-2 (59). As previously mentioned, MBL binds to P. aeruginosa and induces C4 deposition by activating the MASP-2 protease, initiating the lectin pathway (91, 92). When using a C3c (a degraded form of C3) deposition assay with C1q deficient serum, 53% of the P. aeruginosa strains, isolates from CF lung, bloodstream infection, and urinary tract, presented lectin pathway (LP)-mediated activation (93). From all the P. aeruginosa clinical strains, CF-derived isolates presented the highest lectin mediated activation (93). Conversely, a C4c deposition assay (measures a further degraded form of C4b) showed that the P. aeruginosa strain KR 420 triggers the highest lectin pathway activity. However, MASP-2 deficiency in mice did not significantly impact opsonophagocytosis or survival of KR 420 cells, while C3 deficient mice did have a comparatively significant decrease in survival and higher bacterial loads in the lungs (93). Several studies have shown the MBL deficiency is associated with early infection by P. aeruginosa in CF patients (94, 95). Furthermore, MBL deficiency has also been associated with increased chance of the requirement of lung transplant, reduced pulmonary function, and ultimately death (96). Therefore, MASP-2 deficiency per se may not be impacting its susceptibility to P. aeruginosa, likely due to the activity from other complement pathways (93).

As such, multiple complement deficiencies of the host are exploited by P. aeruginosa during infection. Complement protein C3 and therefore the alternative pathway is crucial for survival of the host during P. aeruginosa infection, whereas C4 and the classical pathway seems less critical. Lectin pathway deficiencies lead to worse outcomes for the host during P. aeruginosa infection. However, some of these deficiencies can be overcome by activity from the other complement pathways.

Failure of phagocytic cells to kill P. aeruginosa.

Neutrophils, one of the innate immune systems’ primary phagocytes, are heavily involved in complement-mediated phagocytosis. Neutrophils are known to kill bacteria by releasing granule proteins and chromatin into the extracellular environment to produce neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) (97). Recently, it was discovered that upon induction of NETs, neutrophils also release properdin, Factor B, and C3. These complement contents within NETs can then bind P. aeruginosa and ultimately lead to MAC formation (98). Neutrophil elastase, an enzyme normally stored at high concentrations in primary granules of neutrophils, is involved in the clearance of pathogens during infection (99). Neutrophils treated with neutrophil-derived elastase were impaired in killing P. aeruginosa mucoid and nonmucoid strains, albeit not being impaired for E. coli (100). Furthermore, neutrophil-derived elastase from CF patients has been demonstrated to cleave opsonized iC3b from P. aeruginosa and the CR1 receptor from lung neutrophils, creating a receptor-opsonin mismatch and resulting in worse patient outcomes during P. aeruginosa lung infections (101). This mismatch can be overcome by using engineered bispecific antibodies (specific to both CD18 and O antigen of P. aeruginosa), which restored the levels of neutrophil phagocytosis back to control levels (102). The bronchial lavage of the respiratory tract of CF patients cleaved Pseudomonas-reactive IgG opsonins due to its elastolytic activity, resulting in lower phagocytosis and a continuance of chronic infection (103). It was recently described that CFTR is more highly expressed on macrophages than on neutrophils, and that CFTR-dependent modifications to CD11b (necessary for an effective opsonophagocytosis) occur (104). As such, in individuals with CF, the ability of macrophages, isolated from human peripheral blood, to carry out complement-mediated phagocytosis is impaired, whereas neutrophils remain unaffected (104). Despite all these findings, it was recently demonstrated that when in combination with both complement and several antibiotics, neutrophil elastase kills P. aeruginosa, leaving an ambiguity on the overall effect of neutrophil elastase on complement-mediated killing of P. aeruginosa (105).

HOST COMPLEMENT MOLECULES AND HIJACKING THEREOF BY PSEUDOMONAS AERUGINOSA

Hijacking Factor H and Factor I.

Factor H is a common 155 kDa plasma protein comprised of 20 repeating units of 60 amino acids known as short consensus repeats (SCRs) (106). The SCRs at the N terminus of Factor H bind to C3b, resulting in decay-accelerating activity of the C3 convertase C3bBb (106). Factor H also binds C3b at the 12th to 14th SCRs, and a site at the C terminus, acting as a cell surface regulator while also binding to sialic acid (106). The N-terminal C3b binding site is one important for cofactor activity of Factor I (107), which acts as an inactivator of complement proteins C3b and C4b (108). The most well-known example of Factor H binding by a microorganism is the M protein of Streptococcus pyogenes, which binds the 7th SCR on Factor H but, it can also bind the human complement regulator C4BP, thereby conferring protection to the bacterium from attack by complement (109, 110). Plasminogen has been described as an enhancer to Factor I degradation of C3b and C5 (111). Additionally, Factor H-like protein (FHL-1) is the result of alternative splicing of the gene encoding Factor H (CFH), and five Factor H structurally related proteins encoded by: CFHR1, CFHR2, CFHR3, CFHR4, and CFHR5 near the CFH gene exhibit immunological cross-reaction (112). Factor H accelerates the inactivation of fluid-phase C3b (113), but decay of C3b bound to surfaces depends on the constitution of the surface to which C3b is bound (108), acting as a mechanism in which Factor H can direct the deposition of C3b by selectively permitting C3bBb to assemble on cellular surfaces (113).

The ability of Factor H to inactivate C3b makes it a prime target for pathogenic subversion. P. aeruginosa uses the surface-associated elongation factor Tuf to bind Factor H and FHL-1, recruiting each to its surface where it displays cofactor activity and cleaves C3b (114). Tuf can also bind plasminogen, enabling P. aeruginosa to degrade host extracellular matrices and assist in tissue invasion (114). Once inert plasminogen bound to P. aeruginosa is converted into plasmin, its proteolytic activity results in fibrin degradation in tissues (115). Increased concentrations of Factor H greatly enhance P. aeruginosa survival in human plasma (114). Additionally, microorganisms from different phyla can also bind to Factor H at the 20th domain and use Factor H to evade complement-mediated killing (116).

P. aeruginosa also expresses the 57-kDa dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase LpD, which binds human Factor H, complement Factor H-related protein 1 (CFHR1), and Factor H-like protein 1 (FHL-1), and plasminogen at the SCR 18 to 20, at the C terminus (95). This surface exposed LpD contributes to the evasion of the complement system by P. aeruginosa, as when blocked with antiserum, the P. aeruginosa survival rate is reduced when challenged with human serum compared to controls (117). Additionally, LpD also binds to vitronectin and clusterin (see Hijacking Host Regulatory Proteins), to protect itself from complement protein deposition (118).

Overall, exploitation of Factor H is a powerful strategy used by P. aeruginosa to subvert normal complement activity. Factor H is used by the host to selectively allow the C3 convertase C3bBb formation on foreign surfaces. Currently, it is known that P. aeruginosa expresses two proteins to hijack this activity of Factor H — Tuf and LpD. Each of these proteins have been demonstrated to bind Factor H to cleave or otherwise inactivate C3b, leading to an increase of survival of P. aeruginosa upon serum exposure.

Hijacking host regulatory proteins.

Several host molecules function to check and inhibit certain aspects of the complement system. Vitronectin, one of such molecules, is a human complement inhibitor that binds to the C5b-7 complex, blocking attachment and polymerization of C9, therefore inhibiting the completion of the membrane attack complex (119). P. aeruginosa exploits the presence of this protein by binding to it via complement regulator acquiring surface protein 2 (CRASP-2), thereby inhibiting complement-mediated lysis (120). This has been shown to occur in P. aeruginosa isolated from pneumonia, where the bacteria were found to be bound to host vitronectin in the bronchoalveolar fluid and exhibited greatly increased survival upon serum challenge (121). This process is like the one used by the host where human clusterin binds C5b-C6 and blocks membrane insertion of C5b-7 and C9 assembly (122, 123).

In chronic P. aeruginosa infections, IgG antibodies are created to clear the pathogen; however, there is evidence that “cloaking” antibodies (cAbs) can block or cloak the pathogen from components of the complement system and prevent clearance (124). The mechanism of this cloaking consists of the overproduction of O antigen-specific IgG2 antibodies, which protect P. aeruginosa against complement-mediated killing (125). Plasmapheresis in CF patients resulted in a reduced concentration of cAbs and a restoration of normal bactericidal activity of serum against P. aeruginosa, further corroborating the hypothesized effects of cAbs on complement activity (126).

Alveolar macrophages poorly express complement receptors (127) and exhibit defective binding capability to P. aeruginosa (128), suggesting that P. aeruginosa may have the ability to elude the immune system in the lung. Conversely, the IgG receptor FcγRI is highly expressed by alveolar macrophages and therefore engulfment of P. aeruginosa by these cells is enhanced by IgG, but not by opsonization via complement (129). P. aeruginosa uses type II secretion system (T2SS) as a strategy to subvert innate immunity, with metalloprotease LasB being an important piece of the T2SS. LasB can subvert the activity of alveolar macrophages by downregulating cytokines and complement factors, particularly C3 and Factor B, and downregulating production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by alveolar macrophages (130). LasB can also directly cleave the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β by removing its inhibitory amino terminal prodomain (131).

Human neutrophils (PMNs) exhibit an opposite receptor profile to that of alveolar macrophages and express CR1 and CR3, but not expressing FcγRI, resulting in an increase in engulfment via complement opsonization (100, 129).

In summary, P. aeruginosa exploits several aspects of the host to avoid being killed by the immune response. Complement mediated lysis is inhibited by binding CRASP-2 to vitronectin, which prevents completion of the membrane attack complex. IgG2 antibodies that overproduce O antigen function as cAbs and protect the pathogen by cloaking it from the components of the complement system. Since alveolar macrophages poorly express complement proteins and do not bind well to P. aeruginosa, the pathogen can evade the lung immune system by evading opsonization. The T2SS metalloprotease LasB also enables the pathogen to evade the lung immune system. LasB subverts the alveolar macrophage activity by downregulating cytokines and complement factors. The IgG receptor FcγRI is expressed highly in alveolar macrophages but not PMNs, resulting in an increase in engulfment. Therefore, there are numerous avenues within the host that can be exploited by the pathogen to avoid detection and/or killing by the immune response.

(i) Serpin protein family.

P. aeruginosa also affects serpin proteins. Inhibitor of complement protein 1 (C1Inh), a serine protease inhibitor (serpin), directly inhibits the serine protease activity of both C1s and C1r through irreversible binding (132). The LPS of several Gram-negative organisms, including P. aeruginosa, binds to C1Inh and prevents recognition of the pathogen by the macrophage and the subsequent proinflammatory response (133). As such, C1Inh is under consideration for use to treat inflammatory disorders such as sepsis. Another member of the serpin family, the corticosteroid-binding globulin (CBG), which mediates the release of cortisol (antiinflammatory steroid), is bound by P. aeruginosa elastase resulting in an unfettered release of cortisol and a modulation of inflammation (134).

(ii) Membrane proteins.

To protect against complement lysis, human cells express the membrane protein CD59 which blocks the polymerization of C9 on the C5b-8 complex (18), and also express decay accelerating factor (DAF) protein which accelerates the decay of C4b2a, C3bBb, and C5 convertases (18). Both CD59 and DAF are expressed on the surface of ocular cells; however, when infected with P. aeruginosa, approximately 20% of these membrane-bound factors are cleaved from the host cell (135). Furthermore, recently it was reported that lung epithelial cells depleted of CD59 showed a 60% decrease in invasiveness by P. aeruginosa when infected, indicating that CD59 is required for P. aeruginosa to invade host cells, possibly due to the protection from the complement cascade (136). The complete lack of CD59 and DAF membrane regulators of complement results in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, a condition characterized by increased inflammation and blockage of blood vessels by neutrophils and platelets, and deposition of C3 and subsequent hemolysis of erythrocytes (18). These events can lead to increased susceptibility to opportunistic pathogens and there have been several cases where P. aeruginosa is a leading pathogen that affects these patients (137–139). Likewise, P. aeruginosa has been described as an infective agent in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients, a disease that correlates with low expression of CR1 on erythrocytes and some other cell types (140–142).

(iii) Subclasses of Immunoglobulin G.

The major class of immunoglobulin that activates C1q is IgG, which is further divided into four subclasses IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4 (142). These subclasses are based on the differences in the hinge region known to bind to C1q in the classical pathway of complement (143). Each of the four subclasses display different abilities to activate C1q, with being IgG3 and IgG1 good complement activators, and IgG2 and IgG4 poor activators (143). IgG4 uniquely shows little to no activation of complement (143). In one study it was reported that IgG2 molecules bind the O antigen of P. aeruginosa LPS which blocks the binding sites for other antibodies, including IgG3 and IgG1 antibodies, necessary for the induction of the classical pathway of complement (125). Although IgG2 is typically a poor complement activator, there is some evidence that increased IgG4 levels correlate with lower IgG2 levels and lower opsonic activity, with IgG2 being the better opsonin of the two (144). In uncolonized lungs of CF patients, IgG2 concentrations were shown to be lower, while IgG4 levels were higher, correlating with lower opsonic activity (144). However, upon lung colonization of the CF lung, IgG2 levels and circulating immune complexes (CICs) increase, inhibiting phagocytosis (145). The relationship between complement activation and CIC presence is still unclear, with some reports suggesting low levels of complement activation (146), and other more recent reports indicating higher C3 and C4 activity associated with CICs (147). Furthermore, IgG3 has been found to be present at high levels in CF patients upon chronic P. aeruginosa lung colonization, along with poor pulmonary function and increased neutrophil activity (148). Once IgG3 binds the C1q protein, it is 40 times more likely to activate the classical pathway than IgG2, and 6 times more likely than IgG1. Increased complement activation by IgG3 has also been suggested to increase pulmonary inflammation (148).

To summarize, the IgG subclasses IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4 are involved in complement activation by binding C1q. IgG2 and IgG4 are poor complement activators, while IgG3 and IgG1 are considered good activators of the classical pathway. IgG3 is present at high levels in CF patients and is more likely to activate the classical pathway than IgG2. Higher IgG4 levels correlate with low IgG2 levels and decreased opsonin activity. IgG4 itself confers little to no complement activation. Overall, these results indicate that the composition of IgG subclasses present in the blood directly correlate with levels of complement activation during infection.

(iv) Anaphylatoxins.

Anaphylatoxins, antibacterial peptide fragments generated by activation of the complement system, are important in inflammatory reactions and bacterial clearance (71). The C3a fragment, a 77-amino acid peptide, mediates multiple inflammatory activities and binds to the receptor C3aR which is expressed on myeloid and lymphoid cells (71). Compared to WT mice, C3aR-deficient mice presented decreased neutrophil numbers, fewer inflammatory cells, and decreased chemokine production in the lungs, indicative of a decreased inflammatory response (149). However, this was not reflected in infection, as C3aR-deficient mice had significantly fewer bacteria in the lungs and disseminated in the blood compared to the WT (149).

The C5a anaphylatoxin is partly involved in regulating Fcγ receptor expression (150) and interacts with a primary receptor (C5aR) and a secondary receptor (C5L2) (151). Fcγ receptors are found on myeloid cells and can have stimulatory or inhibitory functions such as promoting phagocytosis or cytokine release (150, 152). They are selective for the Fc region on immunoglobulins (IgG) (150, 152). C5a binding of C5aR initiates a G protein signal transduction leading to FcγRIII (stimulatory) activity. Other stimulatory Fcγ receptors include FcγR1 and FcγRIV, while FcγII is inhibitory (152). C5a and C5aR are directly involved in the regulation of Fcγ receptors by suppressing FcγRII and inducing FcγRIII (153). C5a is associated with a high FcγRIII to FcγRII ratio in infected mice (150). C5aR is necessary for mucosal clearance of P. aeruginosa, as mice deficient in C5aR cannot clear intrapulmonary P. aeruginosa and as such, succumb to pneumonia despite increased neutrophil numbers (154). Similarly, C5a deficiency and FcγRIII deficiency in mice both reduce bacterial clearance and significantly reduce survival (154). FcγRIII deficiency is also associated with increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α (150).

The concentrations of anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a have recently been linked to CF disease progression. Increased levels of C5a correlated with higher inflammation, P. aeruginosa growth in the sputum, and worsened patient outcomes, while heightened C3a levels were correlated with less inflammation and better patient outcomes. (155, 156). P. aeruginosa proteases elastase B (LasB) and alkaline protease (AprA) can cleave C5a (157). Paradoxically, CF P. aeruginosa isolates typically lack these two proteases, causing an accumulation of C5a, which increases neutrophil attraction and neutrophil dysfunction, leading to inflammation and reduced bacterial clearance (157). Furthermore, incubation of soluble fractions of CF sputum with P. aeruginosa increased C5a levels, whereas incubation with Peptide inhibitor of complement 1 (PIC1) prevents this increase (155). The interaction between complement and Fcγ receptors also leads to damaging inflammatory responses against immune complexes (152). The proinflammatory properties of C5a may also contribute to CF lung damage, as lung fluid from CF patients contains increased levels of C5a and incubation of soluble fractions from sputum samples of CF patients with P. aeruginosa or S. aureus also increases C5a production by 2.3-fold (155). Furthermore, C5a is involved in increased vascular permeability, smooth muscle contraction, and histamine release and stimulates neutrophil migration, which leads to degranulation (155). Neutrophil elastase released by neutrophil granules causes lung damage and viscous DNA from degranulation contributes to airway obstruction.

To summarize, anaphylatoxins such as C3a and C5a, have several roles in inflammation. The C3aR receptor on myeloid and lymphoid cells is involved in regulating inflammatory activities mediated by C3a binding. The Fcγ receptor, involved in both stimulatory and inhibitory immune functions, is partially regulated by C5a. Both C3a and C5a are also linked to CF disease progression where: (i) high C3a correlates with lower inflammation levels, and (ii) high C5a correlates with higher inflammation levels.

THERAPEUTICS ADVANCES AGAINST P. AERUGINOSA

Overall P. aeruginosa has several means to evade, undermine, subvert, and hijack the human complement system. As such, there is a growing need to find therapeutics that will circumvent this. One such method is the removal of cloaking antibodies (cAbs) that block complement deposition on microorganisms (125, 158). Lung transplant patients with cAbs specific to LPS O antigen of P. aeruginosa exhibited reduced survival (159); however, removal of cABs by plasmapheresis led to restoration of host complement activity and improved clinical outcomes (126, 160). The use of monoclonal antibodies is also a potential option. Pretreatment of otitis media patients with anti-OprF MAb can significantly reduce the P. aeruginosa invasion of human middle ear epithelial cells (HMEEC) after activation of the PKC pathway by phosphorylation of PKC-α (161). OprF controls the production of several quorum sensing dependent virulence factors, including pyocyanin, elastase, and exotoxin A and is likely to be implicated in immune subversion by P. aeruginosa (161).

Recently, it was also demonstrated that lytic phage therapy can reduce bacterial loads and increased complement-mediated lysis in serum resistant multi-drug resistant (MDR) P. aeruginosa (162), confirming prior phage therapy results (163, 164) and establishing a link to increased complement efficacy. Combinatorial treatment of MDR Gram-negative bacteria with serum and Gram-positive antibiotics has also resulted in unusual sensitivity of these bacteria to Gram-positive specific antibiotics due to the pores formed by complement’s MAC, giving novel options to treat the drug resistant microbes (165). Additionally, hydrolase treatment of P. aeruginosa biofilms led to increased complement deposition, neutrophil uptake, and reactive oxygen species production, giving rise to the idea biofilm disruption may be necessary for ideal complement activity (166).

CONCLUSIONS

While treatment of chronic P. aeruginosa infections has progressed in recent years, many infections stay unresolved and deleterious to the patient. The interactions between the complement system and P. aeruginosa remains a roadblock for the resolution of chronic infections. Recently there have been some advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms used by P. aeruginosa to evade the complement system and innate immunity (Summarized in Table 2). However, therapeutics to treat this problem have been unforthcoming, leaving a need to advance research efforts in this regard. Considering the implications of increased morbidity and mortality of chronic P. aeruginosa infection, further investigation in this matter would prove crucial in both reducing the health care burden and developing novel treatments.

TABLE 2.

Characterization of P. aeruginosa defense strategies and molecular interactions

| Defense strategies | Description | Overall effect | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell States | Biofilm State | Bacterial cells are encased in an extracellular matrix composed of exopolysaccharides, proteins, exogenous DNA (eDNA), RNA, and host polymers. | Tolerant to antimicrobials and the immune response. | 25, 41–44 |

| Persister cell state | A metabolically dormant/low metabolic state, persister cells are a subset (0.0001 to 1%) of the regular vegetative bacterial population | Tolerant to antimicrobials and the immune response. | 45 – 51 | |

| Produced | Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Composed of lipid A, oligosaccharide, and O antigen, found on the outer membrane of P. aeruginosa. | Strains with lengthened O antigen side chains are typically resistant to complement attack in serum. | 30 |

| Psl | An exopolysaccharide involved in the interactions between biofilms and other surfaces. | Inhibit opsonization of the bacterial surface in mucoid strains and decreases deposition of C3, C5, and C7 resulting in decreased opsonization and killing by phagocytes. | 53 – 55 | |

| Ecotin | A serine-protease which binds to Psl. | Protects against neutrophil elastase in both biofilm-associated and planktonic P. aeruginosa. It has also been shown to inhibit MASP-1, MASP-2, and MASP-3 (the primary Factor D activator in human blood). | 57, 58 | |

| Surface-exposed LpD | A 57-kDa dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (LpD) which is exposed on the surface of the cell and can bind human Factor H, complement Factor H-related protein 1 (CFHR1), Factor H-like protein 1 (FHL-1), and plasminogen. Also binds to vitronectin and clusterin. | Enables evasion of complement pathway by binding complement regulators, inhibiting activation and by binding to vitronectin and clusterin in the host, which inhibit complement by preventing formation of the membrane attack complex. | 90, 112, 113 | |

| AprA | A 50-kDa metalloprotease which can degrade several complement proteins, and has been demonstrated to decrease phagocytosis of P. aeruginosa. | Decreases C3b deposition by competitively cleaving C2; it has also been proven to prevent the formation of the chemotactic agent C5a. | 61, 65–67 | |

| Protease IV | A 26-kDa molecule which has been demonstrated to degrade complement proteins. | Degrades C1q and C3, as well as fibrinogen, plasminogen, immunoglobulin G, and some host defense molecules. | 68 – 70 | |

| P. aeruginosa small protease (PASP) | A protease which cleaves collagens, leading to erosion of the cornea in the eye. | Allows for the dysregulation of complement via protease IV activity, thereby contributing to Pseudomonas keratitis. | 72 | |

| Polysaccharide monooxygenase CbpD | A chitin-oxidizing virulence factor which protects P. aeruginosa from MAC-mediated killing. | Downregulates C4, apoptosis, and cell-cycle related genes in host. | 21–70, 72–77 | |

| RhlR | A quorum sensing regulator. | Contributes to the evasion of opsonization by complement-like protein TEP4 in Drosophila melanogaster. | 78 | |

| Elastase B (Las B) | Part of the type II secretion system; a zinc metalloprotease which inactivates the anaphylatoxin activity of C5a via cleavage. | Decreased proinflammatory response from C5a cleavage; subverts the activity of alveolar macrophages and downregulate cytokines and complement factors. | 84, 125, 154 | |

| PhoP/PhoQ System | PhoQ detects Mg2+ and decreases oprH expression which has been found to bind C3 and increase phagocytosis. | Decreased C3 deposition due to decreased oprH expression. | 60, 61 | |

| Mechanisms | Sialic acid binding | P. aeruginosa cells bound to sialic acid also bind strongly to inhibitory siglec-9 and siglec-7, found on monocytes and natural killer cells. | Decreased C3 deposition due to a weakened immune response. | 62 – 64 |

| O-acetylation of alginate | Alginate is an extracellular polysaccharide produced by P. aeruginosa which is O-acetylated on mannuronic acid residues in mucoid CF-associated strains. | Confers resistance to complement-mediated opsonization. | 60 | |

| Lack of methylesterase wspF | Leads to the overproduction c-di-GMP and some biofilm matrix components. | Enables bacteria to avoid engulfment by neutrophils. | 52 |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the support from Binghamton University structural funds, and the ASM travel award to attend and present at the ASM Conference on Biofilms 2022.

C.J.H., C.N.H.M., and S.S.S. cowrote the paper. All authors participated in the literature review and the discussion of findings.

We declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Cláudia Nogueira Hora Marques, Email: cmarques@binghamton.edu.

George O'Toole, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gaspar MC, António A, Canelas Pais C, Simões De Sousa JJ. 2013. New treatment approaches of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis lung disease. J Compr Ped 4:203–204. doi: 10.17795/compreped-13822. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalle M, Papareddy P, Kasetty G, Mörgelin M, van der Plas MJA, Rydengård V, Malmsten M, Albiger B, Schmidtchen A. 2012. Host defense peptides of thrombin modulate inflammation and coagulation in endotoxin-mediated shock and Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis. PLoS One 7:e51313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finch S, McDonnell MJ, Abo-Leyah H, Aliberti S, Chalmers JD. 2015. A comprehensive analysis of the impact of Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization on prognosis in adult bronchiectasis. 12:1602–1611. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201506-333OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Vidal C, Almagro P, Romaní V, Rodríguez-Carballeira M, Cuchi E, Canales L, Blasco D, Heredia JL, Garau J. 2009. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbation. A prospective study. Eur Respir J 34:1072–1078. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00003309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones AM, Dodd ME, Morris J, Doherty C, Govan JRW, Webb AK. 2010. Clinical outcome for cystic fibrosis patients infected with transmissible Pseudomonas aeruginosa: an 8-year prospective study. Chest 137:1405–1409. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lachiewicz AM, Hauck CG, Weber DJ, Cairns BA, van Duin D. 2017. Bacterial infections after burn injuries: impact of multidrug resistance. Clin Infect Dis 65:2130–2136. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rojas A, Palacios-Baena ZR, López-Cortés LE, Rodríguez-Baño J. 2019. Rates, predictors and mortality of community-onset bloodstream infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 25:964–970. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X, Mosser DM. 2008. Macrophage activation by endogenous danger signals. J Pathol 214:161–178. doi: 10.1002/path.2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang JM, An J. 2007. Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. Int Anesthesiol Clin 45:27–37. doi: 10.1097/AIA.0b013e318034194e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarma JV, Ward PA. 2011. The complement system. Cell Tissue Res 343:227–235. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1034-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rus H, Cudrici C, Niculescu F. 2005. The role of the complement system in innate immunity. Immunol Res 33:103–112. doi: 10.1385/IR:33:2:103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagasawa S, Stroud RM. 1977. Cleavage of C2 by C1s into the antigenically distinct fragments C2a and C2b: demonstration of binding of C2b to C4b. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 74:2998–3001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.7.2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallis R, Dodd RB. 2000. Interaction of mannose-binding protein with Aassociated serine proteases. J Biol Chem 275:30962–30969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kozono H, Parker D, White J, Marrack P, Kappler J. 1995. Multiple binding sites for bacterial superantigens on soluble class II MHC molecules. Immunity 3:187–196. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schartz ND, Tenner AJ. 2020. The good, the bad, and the opportunities of the complement system in neurodegenerative disease. J Neuroinflammation 17:1–25. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-02024-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroeder H, Skelly PJ, Zipfel PF, Losson B, Vanderplasschen A. 2009. Subversion of complement by hematophagous parasites. Dev Comp Immunol 33:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hopkins N, Regan M, Abell J. 1997. On the context dependence of national stereotypes: some Scottish data. British J Social Psychology 36:553–563. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1997.tb01149.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan P, Harris C. 1999. Complement regulatory proteins. Academic Press. Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ames RS, Li Y, Sarau HM, Nuthulaganti P, Foley JJ, Ellis C, Zeng Z, Su K, urewicz AJ, Hertzberg RP, Bergsma DJ, Kumar C. 1996. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human anaphylatoxin C3a receptor. J Biol Chem 271:20231–20234. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tschopp J, Amiguet P, Schäfer S. 1986. Increased hemolytic activity of the trypsin-cleaved ninth component of complement. Mol Immunol 23:57–62. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(86)90171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kindt TJ, Goldsby RA, Osborne B, Janis K. 2007. Kuby immunology. 27. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stover C, Endo Y, Takahashi M, Lynch NJ, Constantinescu C, Vorup-Jensen T, Thiel S, Friedl H, Hankeln T, Hall R, Gregory S, Fujita T, Schwaeble W. 2001. The human gene for mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease-2 (MASP-2), the effector component of the lectin route of complement activation, is part of a tightly linked gene cluster on chromosome 1p36.2–3. Genes Immun 2:119–127. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fearon DT, Daha MR, Weiler JM, Austen KF. 1976. The natural modulation of the amplification phase of complement activation. Transplant Rev 32:12–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1976.tb00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Podack ER, Tschoop J, Muller-Eberhard HJ. 1982. Molecular organization of C9 within the membrane attack complex of complement. Induction of circular C9 polymerization by the C5b-8 assembly. J Exp Med 156:268–282. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.1.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boucher RC. 2004. New concepts of the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Eur Respir J 23:146–158. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00057003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koch C. 2002. Early infection and progression of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Pediatr Pulmonol 34:232–236. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassett DJ, Cuppoletti J, Trapnell B, Lymar SV, Rowe JJ, Yoon SS, Hilliard GM, Parvatiyar K, Kamani MC, Wozniak DJ, Hwang SH, McDermott TR, Ochsner UA. 2002. Anaerobic metabolism and quorum sensing by Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in chronically infected cystic fibrosis airways: rethinking antibiotic treatment strategies and drug targets. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 54:1425–1443. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sauer K, Stoodley P, Goeres DM, Hall-Stoodley L, Burmølle M, Stewart PS, Bjarnsholt T. 2022. The biofilm life cycle: expanding the conceptual model of biofilm formation. Nat Rev Microbiol 20:608–620. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00767-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lam J, Chan R, Lam K, Costerton JW. 1980. Production of mucoid microcolonies by Pseudomonas aeruginosa within infected lungs in cystic fibrosis. Infect Immun 28:546–556. doi: 10.1128/iai.28.2.546-556.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodges NA, Gordon CA. 1991. Protection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa against ciprofloxacin and beta-lactams by homologous alginate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 35:2450–2452. doi: 10.1128/AAC.35.11.2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cabral DA, Loh BA, Speert DP. 1987. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa resists nonopsonic phagocytosis by human neutrophils and macrophages. Pediatr Res 22:429–431. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198710000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rocchetta HL, Burrows LL, Lam JS. 1999. Genetics of O-antigen biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 63:523–553. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.63.3.523-553.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huszczynski SM, Lam JS, Khursigara CM. 2019. The role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide in bacterial pathogenesis and physiology. Pathogens 9:6. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9010006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morona R, van den Bosch L, Daniels C. 2000. Evaluation of Wzz/MPA1/MPA2 proteins based on the presence of coiled-coil regions. Microbiology (Reading) 146:1–4. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kintz E, Scarff JM, DiGiandomenico A, Goldberg JB. 2008. Lipopolysaccharide O-antigen chain length regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa serogroup O11 strain PA103. J Bacteriol 190:2709–2716. doi: 10.1128/JB.01646-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hancock RE, Mutharia LM, Chan L, Darveau RP, Speert DP, Pier GB. 1983. Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis: a class of serum-sensitive, nontypable strains deficient in lipopolysaccharide O side chains. Infect Immun 42:170–177. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.1.170-177.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schiller NL, Joiner KA. 1986. Interaction of complement with serum-sensitive and serum-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun 54:689–694. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.3.689-694.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCarthy RR, Mazon-Moya MJ, Moscoso JA, Hao Y, Lam JS, Bordi C, Mostowy S, Filloux A. 2017. Cyclic-di-GMP regulates lipopolysaccharide modification and contributes to Pseudomonas aeruginosa immune evasion. Nat Microbiol 2:1–10. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sebastiá Riquelme AA, Liimatta K, Wong Fok Lung T, Britto CJ, DiMango E, Riquelme SA, Fields B, Ahn D, Chen D, Lozano C, Sáenz Y, Uhlemann A-C, Kahl BC, Prince A. 2020. Clinical and translational report Pseudomonas aeruginosa utilizes host-derived itaconate to redirect its metabolism to promote biofilm formation Pseudomonas aeruginosa utilizes host-derived itaconate to redirect its metabolism to promote biofilm formation. Cell Metab 31:1091–1106.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joiner KA, Goldman RC, Hammer CH, Leive L, Frank MM. 1983. Studies of the mechanism of bacterial resistance to complement-mediated killing. V. IgG and F(ab’)2 mediate killing of E. coli 0111B4 by the alternative complement pathway without increasing C5b-9 deposition. J Immunology 131:2563–2569. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.131.5.2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dasgupta MK, Ward K, Noble PA, Larabie M, Costerton JW. 1994. Development of bacterial biofilms on silastic catheter materials in peritoneal dialysis fluid. Am J Kidney Dis 23:709–716. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)70281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Høiby N, Bjarnsholt T, Givskov M, Molin S, Ciofu O. 2010. Antibiotic resistance of bacterial biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents 35:322–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marvig RL, Sommer LM, Molin S, Johansen HK. 2015. Convergent evolution and adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa within patients with cystic fibrosis. Nat Genet 47:57–64. doi: 10.1038/ng.3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mauch RM, Rossi CL, Aiello TB, Ribeiro JD, Ribeiro AF, Høiby N, Levy CE. 2017. Secretory IgA response against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the upper airways and the link with chronic lung infection in cystic fibrosis. Pathog Dis 75:69. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftx069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Secor PR, Michaels LA, Ratjen A, Jennings LK, Singh PK. 2018. Entropically driven aggregation of bacteria by host polymers promotes antibiotic tolerance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115:10780–10785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1806005115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sauer K, Camper A, Ehrlich G, Costerton J, Davies D. 2002. Pseudomonas aeruginosa displays multiple phenotypes during development as a biofilm. J Bacteriol 184:1140–1154. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.4.1140-1154.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stoodley P, Sauer K, Davies DG, Costerton JW. 2002. Biofilms as complex differentiates communities. Annu Rev Microbiol 56:187–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.160705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rybtke M, Hultqvist LD, Givskov M, Tolker-Nielsen T. 2015. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm infections: community structure, antimicrobial tolerance and immune response. J Mol Biol 427:3628–3645. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lewis K. 2010. Persister cells. Annu Rev Microbiol 64:357–372. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shah D, Zhang Z, Khodursky A, Kaldalu N, Kurg K, Lewis K. 2006. Persisters: a distinct physiological state of E. coli. BMC Microbiol 6:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-6-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mina EG, Marques CNH. 2016. Interaction of Staphylococcus aureus persister cells with the host when in a persister state and following awakening. Sci Rep 6:31342. doi: 10.1038/srep31342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iona E, Pardini M, Gagliardi MC, Colone M, Stringaro AR, Teloni R, Brunori L, Nisini R, Fattorini L, Giannoni F. 2012. Infection of human THP-1 cells with dormant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbes Infect 14:959–967. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marques CNH, Hastings CJ, Himmler GE, Patel A. 2023. Immune response modulation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa persister cells. bioRxiv. 2023.01.07.523056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Younger JG, Shankar-Sinha S, Mickiewicz M, Brinkman AS, Valencia GA, Sarma JV, Younkin EM, Standiford TJ, Zetoune FS, Ward PA. 2003. Murine complement interactions with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and their consequences during pneumonia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 29:432–438. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0145OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pestrak MJ, Chaney SB, Eggleston HC, Dellos-Nolan S, Dixit S, Mathew-Steiner SS, Roy S, Parsek MR, Sen CK, Wozniak DJ. 2018. Pseudomonas aeruginosa rugose small-colony variants evade host clearance, are hyper-inflammatory, and persist in multiple host environments. PLoS Pathog 14:e1006842. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ma L, Jackson KD, Landry RM, Parsek MR, Wozniak DJ. 2006. Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa conditional psl variants reveals roles for the psl polysaccharide in adhesion and maintaining biofilm structure postattachment. J Bacteriol 188:8213–8221. doi: 10.1128/JB.01202-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jones CJ, Wozniak DJ. 2017. Psl Produced by mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa contributes to the establishment of biofilms and immune evasion. mBio 8:1–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00864-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mishra M, Byrd MS, Sergeant S, Azad AK, Parsek MR, McPhail L, Schlesinger LS, Wozniak DJ. 2012. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Psl polysaccharide reduces neutrophil phagocytosis and the oxidative response by limiting complement-mediated opsonization. Cell Microbiol 14:95–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thanabalasuriar A, Surewaard BGJ, Willson ME, Neupane AS, Stover CK, Warrener P, Wilson G, Keller AE, Sellman BR, DiGiandomenico A, Kubes P. 2017. Bispecific antibody targets multiple Pseudomonas aeruginosa evasion mechanisms in the lung vasculature. J Clin Invest 127:2249–2261. doi: 10.1172/JCI89652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tseng BS, Reichhardt C, Merrihew GE, Araujo-Hernandez SA, Harrison JJ, MacCoss MJ, Parsek MR. 2018. A biofilm matrix-associated protease inhibitor protects Pseudomonas aeruginosa from proteolytic attack. mBio 9. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00543-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nagy ZA, Szakács D, Boros E, Héja D, Vígh E, Sándor N, Józsi M, Oroszlán G, Dobó J, Gál P, Pál G. 2019. Ecotin, a microbial inhibitor of serine proteases, blocks multiple complement dependent and independent microbicidal activities of human serum. PLoS Pathog 15:e1008232. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pier GB, Coleman F, Grout M, Franklin M, Ohman DE. 2001. Role of alginate O acetylation in resistance of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa to opsonic phagocytosis. Infect Immun 69:1895–1901. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1895-1901.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qadi M, Izquierdo-Rabassa S, Mateu Borrás M, Doménech-Sánchez A, Juan C, Goldberg JB, Hancock REW, Albertí S. 2017. Sensing Mg2+ contributes to the resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to complement-mediated opsonophagocytosis. Environ Microbiol 19:4278–4286. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goodman AL, Merighi M, Hyodo M, Ventre I, Filloux A, Lory S. 2009. Direct interaction between sensor kinase proteins mediates acute and chronic disease phenotypes in a bacterial pathogen. Genes Dev 23:249–259. doi: 10.1101/gad.1739009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tomlinson S, Luzio JP, Tomlinson S, Taylor PW. 1990. Transfer of preformed terminal c5b-9 complement complexes into the outer membrane of viable gram-negative bacteria: effect on viability and integrity. Biochemistry 29:1852–1860. doi: 10.1021/bi00459a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Edwards MS, Nicholson-Weller A, Baker CJ, Kasper DL. 1980. The role of specific antibody in alternative complement pathway-mediated opsonophagocytosis of type III, group B Streptococcus. J Exp Med 151:1275–1287. doi: 10.1084/jem.151.5.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khatua B, Ghoshal A, Bhattacharya K, Mandal C, Saha B, Crocker PR, Mandal C. 2010. Sialic acids acquired by Pseudomonas aeruginosa are involved in reduced complement deposition and siglec mediated host-cell recognition. FEBS Lett 584:555–561. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 68.Crocker PR, Paulson JC, Varki A. 2007. Siglecs and their roles in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 7:255–266. doi: 10.1038/nri2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mishra M, Ressler A, Schlesinger LS, Wozniak DJ. 2015. Identification of OprF as a complement component C3 binding acceptor molecule on the surface of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun 83:3006–3014. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00081-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wooster DG, Maruvada R, Blom AM, Prasadarao NV. 2006. Logarithmic phase Escherichia coli K1 efficiently avoids serum killing by promoting C4bp-mediated C3b and C4b degradation. Immunology 117:482–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sayegh ET, Bloch O, Parsa AT. 2014. Complement anaphylatoxins as immune regulators in cancer. Cancer Med 3:747–758. doi: 10.1002/cam4.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Laarman AJ, Bardoel BW, Ruyken M, Fernie J, Milder FJ, van Strijp JAG, Rooijakkers SHM. 2012. Pseudomonas aeruginosa alkaline protease blocks complement activation via the classical and lectin pathways. J Immunol 188:386–393. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bohnsack JF, Mollison KW, Buko AM, Ashworth JC, Hill HR. 1991. Group B streptococci inactivate complement component C5a by enzymic cleavage at the C-terminus. Biochemical J 273:635–640. doi: 10.1042/bj2730635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bardoel BW, van der Ent S, Pel MJC, Tommassen J, Pieterse CMJ, van Kessel KPM, van Strijp JAG. 2011. Pseudomonas evades immune recognition of flagellin in both mammals and plants. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002206. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Malloy JL, Veldhuizen RAW, Thibodeaux BA, O’Callaghan RJ, Wright JR. 2005. Pseudomonas aeruginosa protease IV degrades surfactant proteins and inhibits surfactant host defense and biophysical functions. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288:409–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Engel LS, Hill JM, Caballero AR, Green LC, O'Callaghan RJ. 1998. Protease IV, a unique extracellular protease and virulence factor from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Biol Chem 273:16792–16797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Park SJ, Kim SK, So YI, Park HY, Li XH, Yeom DH, Lee MN, Lee BL, Lee JH. 2014. Protease IV, a quorum sensing-dependent protease of Pseudomonas aeruginosa modulates insect innate immunity. Mol Microbiol 94:1298–1314. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tang A, Marquart ME, Fratkin JD, McCormick CC, Caballero AR, Gatlin HP, O'Callaghan RJ. 2009. Properties of PASP: a Pseudomonas protease capable of mediating corneal erosions. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50:3794–3801. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jorgensen I, Rayamajhi M, Miao EA. 2017. Programmed cell death as a defence against infection. Nat Rev Immunol 17:151–164. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Askarian F, Uchiyama S, Masson H, Sørensen HV, Golten O, Bunæs AC, Mekasha S, Røhr ÅK, Kommedal E, Ludviksen JA, Arntzen M, Schmidt B, Zurich RH, van Sorge NM, Eijsink VGH, Krengel U, Mollnes TE, Lewis NE, Nizet V, Vaaje-Kolstad G. 2021. The lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase CbpD promotes Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence in systemic infection. Nat Commun 12:1–19. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21473-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Trouw LA, Blom AM, Gasque P. 2008. Role of complement and complement regulators in the removal of apoptotic cells. Mol Immunol 45:1199–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nauta AJ, Bottazzi B, Mantovani A, Salvatori G, Kishore U, Schwaeble WJ, Gingras AR, Tzima S, Vivanco F, Egido J, Tijsma O, Hack EC, Daha MR, Roos A. 2003. Biochemical and functional characterization of the interaction between pentraxin 3 and C1q. Eur J Immunol 33:465–473. doi: 10.1002/immu.200310022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nauta AJ, Raaschou-Jensen N, Roos A, Daha MR, Madsen HO, Borrias-Essers MC, Ryder LP, Koch C, Garred P. 2003. Mannose-binding lectin engagement with late apoptotic and necrotic cells. Eur J Immunol 33:2853–2863. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schultz DR, Miller KD. 1974. Elastase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: inactivation of complement components and complement-derived chemotactic and phagocytic factors. Infect Immun 10:128–135. doi: 10.1128/iai.10.1.128-135.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hong Y, Ghebrehiwet B. 1992. Effect of Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase and alkaline protease on serum complement and isolated components C1q and C3. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 62:133–138. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(92)90065-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schmidtchen A, Holst E, Tapper H, Björck L. 2003. Elastase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa degrade plasma proteins and extracellular products of human skin and fibroblasts, and inhibit fibroblast growth. Microb Pathog 34:47–55. doi: 10.1016/s0882-4010(02)00197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mueller-Ortiz SSL, Drouin SSM, Wetsel RAR. 2004. The alternative activation pathway and complement component C3 are critical for a protective immune response against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a murine model. Infect Immun 72:2899–2906. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.2899-2906.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hostetter MK, Gordon DL. 1987. Biochemistry of C3 and related thiolester proteins in infection and inflammation. Rev Infect Dis 9:97–109. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schiller NL, Hatch RA, Joiner KA. 1989. Complement activation and C3 binding by serum-sensitive and serum-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun 57:1707–1713. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.6.1707-1713.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gharib SA, Vaisar T, Aitken ML, Park DR, Heinecke JW, Fu X. 2009. Mapping the lung proteome in cystic fibrosis. J Proteome Res 8:3020–3028. doi: 10.1021/pr900093j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Møller-Kristensen M, Thiel S, Sjöholm A, Matsushita M, Jensenius JC. 2007. Cooperation between MASP-1 and MASP-2 in the generation of C3 convertase through the MBL pathway. Int Immunol 19:141–149. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Neth O, Jack DL, Dodds AW, Holzel H, Klein NJ, Turner MW. 2000. Mannose-binding lectin binds to a range of clinically relevant microorganisms and promotes complement deposition. Infect Immun 68:688–693. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.2.688-693.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kenawy HI, Ali YM, Rajakumar K, Lynch NJ, Kadioglu A, Stover CM, Schwaeble WJ. 2012. Absence of the lectin activation pathway of complement does not increase susceptibility to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Immunobiology 217:272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McDougal KE, Green DM, Vanscoy LL, Fallin MD, Grow M, Cheng S, Blackman SM, Collaco JM, Henderson LB, Naughton K, Cutting GR. 2010. Use of a modeling framework to evaluate the effect of a modifier gene (MBL2) on variation in cystic fibrosis. Eur J Hum Genet 18:680–684. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]