Abstract

Background

As an additional two million malaria cases were reported in 2021 compared to the previous year, concerted efforts toward achieving a steady decline in malaria cases are needed to achieve malaria elimination goals. This work aimed at determining the factors associated with malaria parasitaemia among children 6–24 months for better targeting of malaria interventions.

Methods

A cross-sectional study analysed 2021 Nigeria Malaria Indicator Survey dataset. Data from 3058 children 6–24 months were analyzed. The outcome variable was children 6–24 months whose parasitaemia was determined using a rapid diagnostic test (RDT). Independent variables include child age in months, mothers’ age, mothers’ education, region, place of residence, household ownership and child use of insecticide-treated net (ITN), exposure to malaria messages and knowledge of ways to prevent malaria. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to examine possible factors associated with malaria parasitaemia in children 6–24 months.

Results

Findings revealed that 28.7% of the 3058 children aged 6–24 months tested positive for malaria by RDT. About 63% of children 12–17 months (aOR = 1.63, 95% CI 1.31–2.03) and 91% of children 18 to 24 months (aOR = 1.91, 95% CI 1.51–2.42) were more likely to have a positive malaria test result. Positive malaria test result was also more likely in rural areas (aOR = 1.79, 95% CI 2.02–24.46), northeast (aOR = 1.54, 95% CI 1.02–2.31) and northwest (aOR = 1.63, 95% CI 1.10–2.40) region. In addition, about 39% of children who slept under ITN had a positive malaria test result (aOR = 1.39 95% CI 1.01–1.90). While children of mothers with secondary (aOR = 0.40, 95% CI 0.29–0.56) and higher (aOR = 0.26, 95% CI 0.16–0.43) levels of education and mothers who were aware of ways of avoiding malaria (aOR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.53–0.90) were less likely to have a malaria positive test result.

Conclusion

As older children 12 to 24 months, children residing in the rural, northeast, and northwest region are more likely to have malaria, additional intervention should target them in an effort to end malaria.

Keywords: Malaria, Nigeria, Children, Parasitaemia, Cross-sectional study

Background

Despite advancements made globally through the implementation of international and national malaria control programmes, malaria still remains a global public health challenge with 247 million cases and 619,000 malaria-related deaths reported in the year 2021 [1]. With an additional two million malaria cases reported in 2021 compared to the previous year, concerted efforts toward achieving a steady decline in malaria cases are needed. Four countries account for 52% of all global malaria deaths with Nigeria accounting for 31% of the deaths [1]. Without accelerated action, the progress expected towards achieving malaria elimination according to the Global Technical Strategy for malaria may be unattained in 2030.

Over the years, pregnant women and children under five are most vulnerable to malaria, with severity and mortality higher among these vulnerable groups [2–5]. Although malaria control strategies target the general population, but intensive efforts focus on the most vulnerable population. In Nigeria, malaria control interventions include the use of insecticide-treated nets (ITN), prevention of malaria in pregnant women (IPTp), seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) in children 6–59 months using sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine, and amodiaquine (SPAQ), prompt diagnosis of malaria cases and treatment with artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) [5]. These interventions have been effective in reducing morbidity and mortality due to malaria [6–8]. As such resulted in 45% decline in malaria prevalence from 42% to 2010 to 23% in 2018 [9]. However, the 2021 Nigeria Malaria Indicator Survey (NMIS) reported a slight decrease (4%) in malaria prevalence to 22% [10].

Without relenting in efforts to tackle the scourge of malaria, investments, innovations, new developments, and initiatives are being put in place to reduce the burden of malaria. In the Nigeria National Malaria Strategic Plan (2021–2025), Intermittent preventive treatment in infant (IPTi) now perennial malaria chemoprevention (PMC) evaluation pilot is proposed for states where seasonal malaria chemoprevention is not implemented. The World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended PMC be extended to children up to 24 months due to increased malaria prevalence among younger children [11]. In addition, WHO recommended RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine for the prevention of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in children living in regions with moderate to high malaria transmission will also be deployed to children in a four dose schedule starting from 5 months of age [11–13]. Deploying PMC and malaria vaccine in addition with existing interventions for malaria prevention would complement efforts to save children in Nigeria. Re-investigating malaria risk factors prior to deployment of new interventions is vital to inform effective delivery of new innovations for malaria prevention in children and achieve the leave no one behind ambition [14].

Prevalence of malaria and associated factors have been explored in pregnant women and delivering mothers [15–17]. Similar study has also been conducted in children under five and children up to 14 years old including neonates [18–22], and the general population [23]. Some studies have also explored prevalence of malaria in young children less than 6 months old [24, 25] and the first year of life [26]. This paper aim to explore factors associated with malaria parasitaemia in children 6–24 months old. Understanding factors associated with malaria parasitaemia in children are essential for better targeting of malaria control efforts.

Methods

This study analysed cross-sectional survey data from 2021 NMIS. Survey was based on a nationally representative sample drawn from all states and local government area of the country. Analysis of NMIS dataset was conducted after adjusting for survey design cluster and non-response using the individual weight contained in the dataset. Population analysed was children 6–24 months. The outcome variable was children 6–24 months whose malaria parasitaemia was determined using rapid diagnostic test (RDT) during the survey. The independent variables included in the analysis include child’s age in months, mothers’ age, mothers’ education, region, place of residence, mothers’ exposure to malaria messages and her knowledge of malaria prevention. Protective factor against the parasite by using an insecticide-treated net (ITN) was explored by including household ownership, and child use of ITN as independent variables. These variables were chosen as previous studies have established their association with malaria parasitaemia [18, 20, 23, 27–31].

Both bivariate and multivariate statistical data analyses were performed using the statistical package Stata/SE 14.0. While bivariate analysis explored the malaria parasitaemia in comparison with the independent variables. The chi-squared test of independence was used to determine any significant associations between malaria parasitaemia and the independent variables. Variables with p-value < 0.2 at bivariate level were included into the logistic regression model and the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio were derived to examine possible factors associated with malaria parasitaemia in children. Significant associations were measured at 5% alpha level (p < 0.05).

Ethical consideration

This study utilized a population based NMIS dataset obtained from The Demographic Health Survey (DHS) Program, which was available online. The survey was approved by National Health Research Ethical Committee of Nigeria (NHREC) and ICF institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from the caregivers of the children to participate in the survey and for blood sample collected from the children. The DHS Program followed regulations for guarding respondents’ privacy while gathering data. DHS also deleted all personally identifiable information from the online-accessible dataset. This study didn’t need any further ethical approvals because the DHS Program already requested and gained approval before the survey. Authors were given permission by the DHS Program to utilize the dataset for this study.

Results

Descriptive analysis presents the sociodemographic characteristics of children 6–24 months and the prevalence of malaria parasitaemia. While bivariate and multivariate analysis determined the factors associated with malaria parasitaemia in children 6–24 months.

Sociodemographic characteristics

A total of 3058 children 6–24 months were included in the study. Table 1 shows the socio demographic characteristics of these children. About 974 (31.8%) were aged 6–11 months; 1031 (33.7%) were aged 12–17 months while 1053 (34.4%) were aged 18–24 months old. Findings revealed that a higher proportion (51.1%) of their mothers were aged 25–34 years. About 43.2% of mothers had no education, while one out of three mother (30.8%) had secondary level of education. A higher proportion of the children (71.6%) reside in rural areas. While 2048 (67.0%) children live in households that had insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) almost half of the children (47.7%) slept under ITN the night before the survey. About 43.4% of mothers of these children were exposed to malaria messages in the last 6 months while 79.4% were aware of ways of preventing malaria.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics and factors associated with malaria parasitaemia in children 6 to 24 months in Nigeria (N = 3058)

| Variables | n (%) | Malaria positive to RDT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | ||

| Child age (months) | |||

| 6–11 months | 974 (31.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 12–17 months | 1031 (33.7) | 1.70 (1.38–2.08) | 1.63 (1.31–2.03) |

| 18–24 months | 1053 (34.4) | 1.66 (1.32–2.09) | 1.91 (1.51–2.42) |

| Mothers age | |||

| 15–24 years | 820 (26.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 25–34 years | 1562 (51.1) | 0.73 (0.59–0.90) | 0.91 (0.73–1.13) |

| 35 years and above | 677 (22.1) | 0.76 (0.58-1.00) | 0.86 (0.65–1.13) |

| Mothers educational level | |||

| No education | 1322 (43.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Primary | 469 (15.3) | 0.66 (0.48–0.88) | 0.76 (0.55–1.04) |

| Secondary | 942 (30.8) | 0.30 (0.23–0.40) | 0.40 (0.29–0.56) |

| Higher | 326 (10.7) | 0.15 (0.10–0.24) | 0.26 (0.16–0.43) |

| Mother heard/seen malaria messages | |||

| No | 1732 (56.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1326 (43.4) | 0.72 (0.58–0.87) | 0.95 (0.76–1.18) |

| Mother know ways to avoid getting malaria | |||

| No | 630 (20.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 2427 (79.4) | 0.55 (0.44–0.70) | 0.69 (0.53–0.90) |

| Sex of household head | |||

| Male | 2868 (93.8) | ||

| Female | 190 (6.2) | ||

| Household own ITN | |||

| No | 1010 (33.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 2048 (67.0) | 1.20 (0.96–1.51) | 0.78 (0.58–1.06) |

| Child slept under ITN | |||

| No | 1601 (52.3) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1457 (47.7) | 1.46 (1.16–1.83) | 1.39 (1.01–1.90) |

| Region | |||

| Northcentral | 554 (18.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Northeast | 506 (16.6) | 1.85 (1.24–2.78) | 1.54 (1.02–2.31) |

| Northwest | 1082 (35.4) | 1.93 (1.33–2.79) | 1.63 (1.10–2.40) |

| Southeast | 232 (7.6) | 0.78 (0.46–1.32) | 1.26 (0.69–2.30) |

| Southsouth | 318 (10.4) | 0.96 (0.60–1.52) | 1.46 (0.85–2.49) |

| Southwest | 365 (11.9) | 0.46 (0.28–0.76) | 0.96 (0.56–1.67) |

| Place of residence | |||

| Rural | 2191 (71.6) | 1.00 | |

| Urban | 867 (28.4) | 2.65 (1.97–3.56) | 1.79 (1.36–2.36) |

Prevalence of malaria parasitaemia

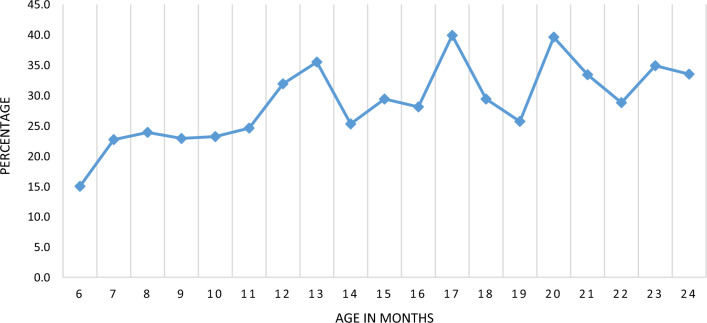

Data on 3058 children 6–24 months analysed revealed 878 (28.7%) of the children tested positive to malaria with RDT. Figure 1 shows prevalence of malaria by age in months. Results show an increase in the malaria cases from 6 months of age, which plateaus between 8 and 10 months and peaked at 13th months, 17th month and 20th months of age. Higher malaria cases were seen in the second year of life compared to the first year of life.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of malaria parasitaemia in children 6–24 months using RDT

Bivariate and multivariate analysis

Table 2 presents the bivariate analysis of the factors associated with malaria parasitaemia in children 6–24 months by sociodemographic characteristics. Findings show that malaria parasitaemia was associated with the age of child in months, age of mother, education of mother, region, place of residence, sleeping under ITN, mothers’ exposure to malaria messages in the past 6 months and knowledge of ways of preventing malaria (p < 0.05). While malaria prevalence in children 6–11 months was 21.9%. Malaria prevalence in children 12–17 months (32.1%) and 18–24 months (31.7%) were significantly higher (P < 0.000). Malaria parasitaemia was also significantly associated with place of residence (P < 0.000). About 33.7% of children in the rural area had a positive malaria test result compared to 16.1% in the urban area. Geographic variation was also observed with Northeast (36.3%) and Northwest (37.2%) having higher prevalence compared to other regions. Children of mothers with secondary (17.3%) and higher level of education (9.4%) were significantly less likely to have a positive test result compared to children whose mother had primary (31.2%) and no education (40.8%). Interestingly, about 32.8% (P < 0.001) of children whose mother reported that they slept under an ITN the night before the survey had a positive test result. While children of mothers’ who have seen or heard malaria messages (24.9%) and mothers’ who know ways of avoiding malaria (26.1%) were significantly less likely (p < 0.001) to have a positive malaria test result.

Table 2.

Malaria parasitaemia in children 6 to 24 months by sociodemographic characteristics

| Variables | Malaria parasitaemia in children 6–24 months | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative n (%) | Positive n (%) | ||

| Child age (months) | 0.000 | ||

| 6–11 months | 761 (78.1) | 213 (21.9) | |

| 12–17 months | 700 (67.8) | 332 (32.1) | |

| 18–24 months | 719 (71.3) | 334 (31.7) | |

| Mothers age | 0.01 | ||

| 15–24 years | 545 (66.5) | 274 (33.5) | |

| 25–34 years | 1144 (73.2) | 418 (26.8) | |

| 35 years and above | 490 (72.5) | 186 (27.5) | |

| Mothers educational level | 0.000 | ||

| No education | 783 (59.2) | 538 (40.8) | |

| Primary | 322 (68.8) | 146 (31.2) | |

| Secondary | 779 (82.7) | 163 (17.3) | |

| Higher | 295 (90.6) | 31 (9.4) | |

| Mother heard/seen malaria messages | 0.001 | ||

| No | 1184 (68.3) | 548 (31.7) | |

| Yes | 995 (75.1) | 330 (24.9) | |

| Mother know ways to avoid getting malaria | 0.000 | ||

| No | 385 (61.1) | 245 (38.9) | |

| Yes | 1794 (73.9) | 633 (26.1) | |

| Household own ITN | 0.110 | ||

| No | 745 (73.8) | 265 (26.2) | |

| Yes | 1434 (70.0) | 614 (30.0) | |

| Child slept under ITN | 0.001 | ||

| No | 1200 (75.0) | 401 (25.1) | |

| Yes | 980 (67.2) | 478 (32.8) | |

| Place of residence | 0.000 | ||

| Rural | 1452 (66.3) | 739 (33.7) | |

| Urban | 727 (83.9) | 140 (16.1) | |

| Region | 0.000 | ||

| Northcentral | 424 (76.5) | 130 (23.5) | |

| Northeast | 323 (63.7) | 184 (36.3) | |

| Northwest | 680 (62.8) | 402 (37.2) | |

| Southeast | 188 (80.7) | 45 (19.3) | |

| South south | 246 (77.3) | 72 (22.7) | |

| South west | 320 (87.6) | 45 (12.4) | |

| Total | 2179 (71.3) | 878 (28.7) | |

Table 1 also presents result of the multivariable logistic regression analysis. Findings show that children 12–17 months were about 63% more likely to have a positive test result (aOR = 1.63, 95% CI 1.31–2.03) while children 18–24 months were 91% more likely to have a positive test result. (aOR = 1.91, 95% CI 1.51–2.42). Similarly, children whose mother have secondary (aOR = 0.40, 95% CI 0.29–0.56) and higher (aOR = 0.26, 95% CI 0.16–0.43) level of education were less likely to have a positive malaria test result. Children residing in rural area were about twice (aOR = 1.79, 95% CI 1.36–2.36) more likely to have a positive malaria test result compared to their counterparts in the urban areas. Similarly, children in the Northeast (aOR = 1.54, 95% CI 1.02–2.31) and Northwest (aOR = 1.63, 95% CI 1.10–2.40) regions were more likely to have a positive malaria test result compared to their counterparts in other regions. Children whose mother stated they slept under ITN the night before the survey were about 39% more likely to test positive to malaria (aOR = 1.39 95% CI 1.01–1.90) while children whose mother know ways to avoid malaria were less likely (aOR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.53–0.90) to have a positive malaria test result.

Discussion

This study examined factors associated with malaria parasitaemia in children 6–24 months by conducting a secondary data analysis of 2021 NMIS dataset. The true prevalence of malaria in children has not been characterized and this is expedient with the epidemiological shift in population at risk to malaria [24, 32]. Findings highlight a malaria prevalence of 28.7% in children aged 6–24 months old using RDT, with prevalence higher in children more than 12 months compared to younger children. This finding confirmed increased malaria prevalence in children more than one year in Nigeria. Previous studies have also reported increased prevalence of malaria with increased age of persons in the population [30, 33, 34]. As prevalence of malaria in these children is higher than 10%, targeted malaria prevention approach is required for this age group. The National Malaria Strategic Plan articulates the countries malaria prevention and control strategies towards a malaria free Nigeria. The newly introduced tool RTS,S malaria vaccine is reported to result in significant reduction in clinical malaria, severe malaria and severe malaria anaemia [35]. Positioning this intervention across the country should be based on evidence on malaria prevalence and possible factors associated with malaria. This study which enables understanding of the factors’ association with malaria in children revealed child age, mother’s education, region, knowledge of ways to prevent malaria and place of residence were associated with malaria parasitaemia in children 6–24 months old. This finding is similar to several other studies. For instance, some studies have documented children residing in rural areas have higher prevalence of malaria than children in urban areas [21, 36]. This is attributed to dirty environments common in rural areas, which increase the likelihood of contacting malaria. Another study also showed that malaria is well acknowledged as a disease of poor communities common in rural areas [17, 37]. As progress made in reducing malaria prevalence in children is a measure to assess the achievement of leave no one behind global ambition [14], additional interventions such as malaria vaccine which has a high potential of reducing inequality of accessing existing intervention should target underserved children to protect them from malaria [38].

Several studies have confirmed sleeping under ITN protects from malaria with reduced prevalence in children who slept under ITN [18, 27, 29]. This study agrees with these findings as majority of the children who slept under ITN were protected, while about 39% of children who slept under ITN had a positive test result. The likelihood of children who used ITN to have malaria has been reported elsewhere [39]. Those that had a positive result could have been exposed to mosquitoes at a time when net was not used [27, 34, 40]. As maternally acquired protection from malaria will have waned after 6 months and a steady increase in malaria cases seen with increase in child age, danger of morbidity and mortality due to malaria need to be averted in these children. Social behaviour change communication (SBCC) has increased the impact of health intervention in hygiene, HIV and nutrition and can improve malaria prevention and treatment behaviour [41–43]. This study has also demonstrated the effect of behaviour change communication (BCC) on malaria as knowledge of malaria was associated with lower prevalence of malaria parasitaemia. As BCC has notably improved behaviour in several interventions, interpersonal communication at community and health facilities should target women with lower level of education whose children have a higher prevalence of malaria to increase their knowledge about malaria prevention and treatment. The identified factors associated to malaria prevalence presented in this study should be considered for better targeting of interventions.

Strength and limitations

This study has a representative sample at regional and national level to guide malaria prevention strategy in children less than two years old and decision-making. Being a cross-sectional study, results captured point prevalence of malaria. As such seasonal trends in malaria transmission was not accounted for in this study.

Conclusion

Older children 12 to 24 months and children residing in the rural areas, northeast and northwest region were more likely to have a positive malaria test result while children whose mothers have a higher level of education and know how to prevent malaria were less likely to have a positive malaria test result. Additional malaria intervention should target children under two years old at higher risk to malaria to attain malaria elimination goals.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACT

Artemisinin-based combination therapy

- BCC

Behaviour change communication

- DHS

Demographic Health Survey

- IPTi

Intermittent preventive treatment in infant

- ITN

Insecticide-treated net

- NHREC

National Health Research Ethical Committee of Nigeria

- NMIS

Nigeria Malaria Indicator Survey

- PMC

Perennial malaria chemoprevention

- RDT

Rapid diagnostic test

- SMC

Seasonal malaria chemoprevention

- SPAQ

Sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine and amodiaquine

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

CNU conceived the idea of the work, conducted statistical data analysis, and drafted the manuscript OAM provided technical oversight to the manuscript development. All authors made valuable input to the concept, review of the manuscript, agreed on all aspect of the work and approved the final version.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency to complete this work. The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used for this work are available with permission in the Demographic Health Survey Program repository, at http://www.dhsprogram.com/data/dataset.

Declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chinazo N. Ujuju and Olugbenga A. Mokuolu contributed equally and are co-first authors.

References

- 1.WHO. World malaria report 2022. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report. Accessed 28 Jan 2023.

- 2.Schantz-Dunn J, Nour NM. Malaria and pregnancy: a global health perspective. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2:186–192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lufele E, Umbers A, Ordi J, Ome-Kaius M, Wangnapi R, Unger H, et al. Risk factors and pregnancy outcomes associated with placental malaria in a prospective cohort of Papua New guinean women. Malar J. 2017;16:427. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-2077-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afoakwah C, Deng X, Onur I. Malaria infection among children under-five: the use of large-scale interventions in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:536. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5428-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO . First malaria vaccine in Africa: a potential new tool for child health and improved malaria control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cairns M, Ceesay SJ, Sagara I, Zongo I, Kessely H, Gamougam K, et al. Effectiveness of seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) treatments when SMC is implemented at scale: case–control studies in 5 countries. PLoS Med. 2021;18:e1003727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baba E, Hamade P, Kivumbi H, Marasciulo M, Maxwell K, Moroso D, Roca-Feltrer A, Sanogo A, Johansson JS, Tibenderana J, Abdoulaye R. Effectiveness of seasonal malaria chemoprevention at scale in West and Central Africa: an observational study. Lancet. 2020;39:1829–1840. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32227-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindblade KA, Mwandama D, Mzilahowa T, Steinhardt L, Gimnig J, Shah M, et al. A cohort study of the effectiveness of insecticide-treated bed nets to prevent malaria in an area of moderate pyrethroid resistance, Malawi. Malar J. 2015;14:31. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0554-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Population Commission (NPC), [Nigeria], and ICF. 2019. Nigeria demographic health survey 2018. Abuja, Nigeria,Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPCICF. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR359/FR359.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan 2022.

- 10.National Malaria Elimination Programme (NMEP) [Nigeria], National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria], and ICF. 2022. Nigeria malaria indicator survey 2021 final report. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NMEP, NPC, and ICF. https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/MIS41/MIS41.pdf. Accessed 28 Jan 2023.

- 11.WHO. Guidelines for malaria (3 June 2022). Geneva: World Health Organization, ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/world/who-guidelines-malaria-3-june-2022. Accessed 14 June 2022.

- 12.Baral R, Levin A, Odero C, Pecenka C, Tabu C, Mwendo E, et al. Costs of continuing RTS,S/ASO1E malaria vaccination in the three malaria vaccine pilot implementation countries. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0244995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van den Berg M, Ogutu B, Sewankambo NK, Biller-Andorno N, Tanner M. RTS,S malaria vaccine pilot studies: addressing the human realities in large-scale clinical trials. Trials. 2019;20:316. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3391-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ren M. Greater political commitment needed to eliminate malaria. Infect Dis Poverty. 2019;8:28. doi: 10.1186/s40249-019-0542-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agomo CO, Oyibo WA. Factors associated with risk of malaria infection among pregnant women in Lagos, Nigeria. Infect Dis Poverty. 2013;2:19. doi: 10.1186/2049-9957-2-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gontie GB, Wolde HF, Baraki AG. Prevalence and associated factors of malaria among pregnant women in Sherkole district, Benishangul Gumuz regional state, West Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:573. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05289-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Limenih A, Gelaye W, Alemu G. Prevalence of malaria and associated factors among delivering mothers in Northwest Ethiopia. BioMed Res Int. 2021;2021:2754407. doi: 10.1155/2021/2754407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Workineh L, Lakew M, Dires S, Kiros T, Damtie S, Hailemichael W, et al. Prevalence of malaria and associated factors among children attending health institutions at South Gondar Zone, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Glob Pediatr Health. 2021;8:2333794X211059107. doi: 10.1177/2333794X211059107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falade C, Mokuolu O, Okafor H, Orogade A, Falade A, Adedoyin O, et al. Epidemiology of congenital malaria in Nigeria: a multi-centre study. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:1279–1287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ajakaye OG, Ibukunoluwa MR. Prevalence and risk of malaria, anemia and malnutrition among children in IDPs camp in Edo State, Nigeria. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2019;8:e00127. doi: 10.1016/j.parepi.2019.e00127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beavogui AH, Delamou A, Camara BS, Camara D, Kourouma K, Camara R, et al. Prevalence of malaria and factors associated with infection in children aged 6 months to 9 years in Guinea: results from a national cross-sectional study. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2020;11:e00162. doi: 10.1016/j.parepi.2020.e00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Habyarimana F, Ramroop S. Prevalence and risk factors associated with malaria among children aged six months to years old in Rwanda: evidence from 2017 Rwanda malaria indicator survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:7975. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duguma T, Nuri A, Melaku Y. Prevalence of malaria and associated risk factors among the community of Mizan-Aman town and its catchment area in Southwest Ethiopia. J Parasitol Res. 2022;2022:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2022/3503317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceesay SJ, Koivogui L, Nahum A, Taal MA, Okebe J, Affara M, et al. Malaria prevalence among young infants in different transmission settings, Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1114. doi: 10.3201/eid2107.142036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folarin OF, Kuti BP, Oyelami AO. Heavy malaria parasitaemia in young nigerian infants: prevalence, determinants and implication for the health system. West Afr J Med. 2022;39:154–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Natama HM, Rovira-Vallbona E, Somé MA, Zango SH, Sorgho H, Guetens P, et al. Malaria incidence and prevalence during the first year of life in Nanoro, Burkina Faso: a birth-cohort study. Malar J. 2018;17:163. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2315-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Awosolu OB, Yahaya ZS, Haziqah MTF, Prevalence Parasite density and determinants of falciparum malaria among febrile children in some peri-urban communities in Southwestern Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:3219–32. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S312519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abossie A, Yohanes T, Nedu A, Tafesse W, Damitie M. Prevalence of malaria and associated risk factors among febrile children under five years: a cross-sectional study in Arba Minch Zuria District, South Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:363–372. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S223873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed A, Mulatu K, Elfu B. Prevalence of malaria and associated factors among under-five children in Sherkole refugee camp, Benishangul-Gumuz region, Ethiopia. A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0246895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sultana M, Sheikh N, Mahumud RA, Jahir T, Islam Z, Sarker AR. Prevalence and associated determinants of malaria parasites among Kenyan children. Trop Med Health. 2017;45:25. doi: 10.1186/s41182-017-0066-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morakinyo OM, Balogun FM, Fagbamigbe AF. Housing type and risk of malaria among under-five children in Nigeria: evidence from the malaria indicator survey. Malar J. 2018;17:311. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2463-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D’Alessandro U, Ubben D, Hamed K, Ceesay SJ, Okebe J, Taal M, et al. Malaria in infants aged less than six months—is it an area of unmet medical need? Malar J. 2012;11:400. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dawaki S, Al-Mekhlafi HM, Ithoi I, Ibrahim J, Atroosh WM, Abdulsalam AM, et al. Is Nigeria winning the battle against malaria? Prevalence, risk factors and KAP assessment among Hausa communities in Kano State. Malar J. 2016;15:351. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1394-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts D, Matthews G. Risk factors of malaria in children under the age of five years old in Uganda. Malar J. 2016;15:246. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1290-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.RTS,S Clinical Trials Partnership Efficacy and safety of, RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine with or without a booster dose in infants and children in Africa: final results of a phase 3, individually randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:31–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60721-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yankson R, Anto EA, Chipeta MG. Geostatistical analysis and mapping of malaria risk in children under 5 using point-referenced prevalence data in Ghana. Malar J. 2019;18:67. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-2709-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yusuf OB, Adeoye BW, Oladepo OO, Peters DH, Bishai D. Poverty and fever vulnerability in Nigeria: a multilevel analysis. Malar J. 2010;9:235. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Unwin HJT, Mwandigha L, Winskill P, Ghani AC, Hogan AB. Analysis of the potential for a malaria vaccine to reduce gaps in malaria intervention coverage. Malar J. 2021;20:438. doi: 10.1186/s12936-021-03966-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wanzira H, Katamba H, Okullo AE, Agaba B, Kasule M, Rubahika D. Factors associated with malaria parasitaemia among children under 5 years in Uganda: a secondary data analysis of the 2014 malaria indicator survey dataset. Malar J. 2017;16:191. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsegaye AT, Ayele A, Birhanu S. Prevalence and associated factors of malaria in children under the age of five years in Wogera district, northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0257944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koenker H, Keating J, Alilio M, Acosta A, Lynch M, Nafo-Traore F. Strategic roles for behaviour change communication in a changing malaria landscape. Malar J. 2014;13:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wakefield MA, Loken B, Hornik RC. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet. 2010;376:1261–1271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Curtis V, Kanki B, Cousens S, Diallo I, Kpozehouen A, Sangaré M, et al. Evidence of behaviour change following a hygiene promotion programme in Burkina Faso. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:518–527. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used for this work are available with permission in the Demographic Health Survey Program repository, at http://www.dhsprogram.com/data/dataset.