BACKGROUND

The transition from medical school to clinical practice has long been regarded as a stressful transition and is associated with high levels of anxiety and burnout among trainees(1–6).

The anxiety and stress are secondary to a complex mix of factors including shift work, increased workload, increased responsibility, a shift in working relationships and in their professional identity.

A systematic review seeking to understand how prepared UK medical graduates are for practice and the effectiveness of workplace transition interventions noted that in many aspects of this difficult transition medical students have not been well prepared by their training institutions. These aspects include multidisciplinary team working, understanding how the clinical environment works, time management, clinical reasoning and making diagnoses (4).

Whilst induction, shadowing and assistantships are of some benefit, graduates continue to be unprepared in many areas for this transition with it generating high levels of stress and burnout, particularly for those individuals with an anxious disposition (1). Considering this and in order to address the unmet and difficult-to-reach areas of unpreparedness, there is a need for a novel approach to help smooth the transition into clinical practice. This is not only important for junior doctor well-being but also for patient safety(7,8).

Peer Assisted Learning (PAL) is defined as “the acquisition of knowledge and skill through active helping and supporting among status equals or matched companions” (9). PAL has the potential to address some of the challenges associated with the transition from medical school to clinical practice. Its strengths are based on the use of teachers with experience, empathy, and expertise specific to the challenges of the transition. For instance, they can help with issues relating to the formation of their professional identity, the provision of practical and emotional support for trainees, and creating a non-judgemental environment where anxieties can be explored more openly(10,11). Some of the key strengths PAL brings to assisting in this transition are cognitive and social congruence, with their value being demonstrated in supplemental PAL teaching programmes such as Lockspeiser et al(12). Cognitive congruence refers to the ability of a peer to teach at an appropriate level approaching the subject matter with a shared or similar understanding(13). Social congruence then refers to a willingness to engage with the peer in an authentic and sincere manner(13,14).

The peer-assisted perspective is important in the induction process as medical technology and structures are constantly changing and therefore experts in the current challenges facing those about to transition are those who are going through or have just transitioned. The recent COVID pandemic made this particularly pertinent as the normal healthcare and organisational structures were in constant flux.

AIMS

Our goal was to smooth the transition for final-year medical students as they stepped into clinical practice using PAL in two main ways:

By reflecting on our own experience of the transition identifying catch points of particular difficulty. Our goal was then to develop a “bespoke teaching programme” to pass on our learning in these areas expediting and soothing their learning experience.

Creating a relaxed environment encouraging social congruence and facilitating the development of professional identity while establishing freedom to explore their anxieties. This allows the student to discuss topics they would not feel confident or appropriate to bring to a superior or supervisor, stimulates discussion and helps the student process the learning at a deeper level.

METHOD

We carried out a pilot study of PAL for final year medical students on their final year assistantship at the Western Health and Social Care Trust (a final placement with opportunity to shadow a Foundation Year 1 (FY1) doctor and grow in confidence in completing the ward work of a FY1 doctor). We wanted to assess the feasibility and carry out an initial assessment of its effectiveness in improving the levels of preparedness of graduates transitioning from medical school to clinical practice.

A FY1 focus group of doctors identified 6 aspects of the transition from medical school to professional life. The doctors were selected for having had different experiences of the transition, from doctors native to the area who had studied abroad and had not been previously exposed to the hospital, doctors who were not local but studied at the medical school, international doctors who had started with no prior knowledge of the hospital structure or medical school, and finally doctors who were local and studied at the medical school. The focus group elicited from personal experience, areas that had not been fully addressed in their undergraduate training or Trust induction. The areas identified were as follows: The role of a FY1 doctor, preparing for nightshifts, working with nurses, well-being and managing stress, finances and e-portfolio.

A wider perspective was sought from a larger group of FY1s. A pre-course survey established baseline data from a group of 30 final-year students who were currently doing their final-year assistantship. This survey used a self-reported measure of how prepared the students felt in 5 of the areas we identified before asking for their input into areas of concern or anxiety they wanted to address. Six 30-minute teaching sessions were then developed incorporating all input received. These were scheduled by the Western Trust Medical Education Department over the lunch breaks of the FY1 doctors leading the sessions. Of note their breaks were extended to ensure an adequate rest period). Sessions were in the student’s free time with attendance not being compulsory. The sessions were then delivered in a comfortable environment with an emphasis on designing a safe space. In order to create this environment we delivered the session over food/coffee and were sitting around a table together. The sessions were structured as a discussion, avoiding formal presentations or didactic teaching and by addressing and treating the students as contemporary colleagues. Iterative evaluation of each session was sought with dynamic response to individual feedback. A post-course survey was completed to measure self-reported sense preparedness and identify areas for improvement. This was in the form of free text questions followed by statements of preparedness with which they could agree or disagree or remain neutral.

CONTENT OF SESSIONS

The role of a FY1 doctor: Detailed description of day-to-day responsibilities and shift structure, how this differs from medical to surgical jobs, how to hand over and how to meet your FY1 responsibilities most efficiently within the hospital structure and processes.

Preparing for nightshifts: Common worries, preparation pre and post nights, responsibilities, prioritisation, escalation and common scenarios.

Working with nurses: Understanding the differences in responsibilities, priorities and culture, Common clash points and how to deal with them and the importance of communication.

Wellbeing: Physical and mental strain of starting F1, supporting colleagues, recognising when you need a break, managing chaos: organisation and prioritisation, post-work anxiety and ‘switching off’.

Finances: Pay, tax, student Finance, locums, medical unions and pension.

E-portfolio: Understanding *TURAS, ARCP requirements & the FY1 curriculum and Career progression (*Online e-portfolio platform for demonstrating competencies as required by the FY1 Curriculum).

RESULTS

Our pre-course survey was completed by all 30 students completing their assistantship at the time. The post-course survey was completed by 13 of the participants.

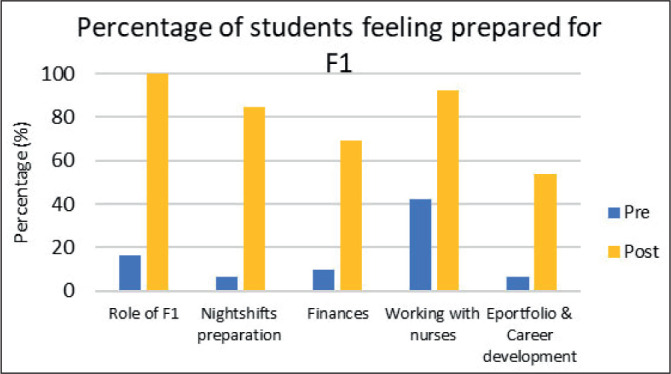

In response to the question “How do you feel about starting FY1?”, 70% responded by describing feeling “nervous”, “scared” or “underprepared”. In response to the statement “I understand the day-to-day role of an FY1 doctor” only 16% agreed or strongly agree with this statement. In the post-course survey, this increased to 100%. In response to the statement “I feel prepared for working nightshifts as a Fy1 doctor” only 6% responded with agree or strongly agree with the statement increasing to 85% in the post-course survey. In response to the statement “I understand the UK Foundation Programme ARCP requirements” only 6% agreed or strongly agreed, increasing up to 54% in the post-course survey. When asked about working with the multidisciplinary team 42% had a positive response increasing to 92%. When asked about the salary of a junior doctor and the expenses they should expect 10% responded positively increasing to 69%. When asked what the students would most like to learn or have covered at the sessions the majority responded with issues that we already were planning to incorporate into one of the 6 sessions. Common themes included work-life balance, general tips for being an effective FY1, prioritising jobs, coping with stress, CV building, rotas and annual leave, expectations from seniors and the multidisciplinary team, ward politics and ward cultures, who to approach for support and dealing with nights.

Key findings:

All areas saw significant improvements in self-reported preparedness.

The session with the biggest increase in self-reported preparedness (16% to 100%) was the “Role of a FY1 doctor”. 100% of participants found the teaching programme helpful in their preparation for practice.

DISCUSSION

This pilot study showed that PAL can be facilitated for final-year medical students transitioning into clinical practice. It also showed that PAL can be a method of improving levels of preparedness for graduates transitioning from medical school to clinical practice. It received high levels of positive feedback from both students and the medical education staff at the Western Health and Social Care Trust.

The strengths that PAL offers in this difficult transition practice include the experience of support for trainees, the building of professional identity and teaching from “experts” in dealing with the challenges of the transition. All of these have been shown to help relieve student anxiety, smooth the transition, and contribute to doctor well-being and patient safety. Another strength of PAL is the individual nature that it allows with tailoring specific both to the student, the teacher and the institution involved. This not only allows flexibility for different personalities and individuals to express and discuss their concerns but allows effective navigation for particular challenges in each hospital, its context, and the culture of its working environments.

This study has several limitations. The evaluation does not provide insight into the student’s experience after their transition into professional life at the start of F1 and so fails to assess if the transition was truly smoothed. Additionally, there is no control group for comparison. The results were gained through survey feedback to tutors known to the students throughout the teaching programme. Students may have responded more positively in a natural desire to express appreciation and goodwill towards their tutors. The survey response was low at 43%. This may have introduced a response bias where the most enthusiastic students were the primary ones to respond. Furthermore, it can be expected that trainees as they make this transition would naturally become more comfortable with their job over time, particularly as they complete their assistantship. While the improvement in how prepared they felt about ‘the role of the Foundation doctor’ is striking it is not clear to what degree the improvement is attributable to our course or to the final year assistantship given that they were completed simultaneously.

The trainees undergoing this transition were Queen’s University Belfast (QUB) medical students following the universities assistantship curriculum, based on GMC advice for curriculum design. It is therefore reasonable to expect similar results elsewhere in the UK. However, the sample size is small and has only been conducted in hospitals within Northern Ireland. Hence the generalizability of the success of this study to other contexts and cultures is uncertain. Furthermore, the identification of the unmet learning requirements in the medical curriculum for doctors as they make this transition was drawn from a small number of doctors in a 3–4-week time frame. The focus group and discussion were therefore more of a snapshot of doctors’ reflections of their transition at a stationary point and from a limited perspective in the Western Trust of the Northern Ireland Deanery. Following individuals through the transition at multiple points in time and from several different perspectives would be more effective in uncovering the layers of complexity involved in this difficult and complex transition.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Healthcare Trusts and Medical Schools should consider the use of PAL to help final-year students transition into clinical practice. It can add value as a formal part of Trust induction, or the final year assistantship as final year students get expert advice from those who have just experienced the challenges of the transition. They also develop their professional identity and experience support from their colleagues as they step into training.

More formal and detailed qualitative work using focus groups similar to the one described in this paper delving into the gaps in the current medical education curriculum for final-year medical students as they make this transition would be invaluable. Well-planned longitudinal qualitative research will provide a much greater understanding of the challenges experienced and possible solutions while a more robust measurement of the effectiveness of PAL in addressing these gaps in training will create more reliable and generalizable data for medical schools and healthcare trusts alike.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

MedEdWest, the education arm of the Western Health and Social Care Trust who, with kindness and enthusiasm supported, encouraged and facilitated the teaching series.

Footnotes

UMJ is an open access publication of the Ulster Medical Society (http://www.ums.ac.uk).

REFERENCES

- 1.Monrouxe Lv, Bullock A, Tseng HM, Wells SE. Association of professional identity, gender, team understanding, anxiety and workplace learning alignment with burnout in junior doctors: a longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017 Dec 27;7(12):e017942. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Donnell M, Noad R, Boohan M, Carragher A. Foundation programme impact on junior doctor personality and anxiety in Northern Ireland. Ulster Med J. 2012 Jan;81(1):19–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markwell AL, Wainer Z. The health and wellbeing of junior doctors: insights from a national survey. Medical Journal of Australia. 2009 Oct 19;191(8):441–4. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monrouxe Lv, Grundy L, Mann M, John Z, Panagoulas E, Bullock A, et al. How prepared are UK medical graduates for practice? A rapid review of the literature 2009–2014. BMJ Open. 2017 Jan 13;7(1):e013656. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lundin RM, Bashir K, Bullock A, Kostov CE, Mattick KL, Rees CE, et al. “I’d been like freaking out the whole night”: exploring emotion regulation based on junior doctors’ narratives. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2018 Mar 17;23(1):7–28. doi: 10.1007/s10459-017-9769-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nason GJ, Liddy S, Murphy T, Doherty EM. A cross-sectional observation of burnout in a sample of Irish junior doctors. Ir J Med Sci. 2013 Dec 6;182(4):595–9. doi: 10.1007/s11845-013-0933-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willcock SM, Daly MG, Tennant CC, Allard BJ. Burnout and psychiatric morbidity in new medical graduates. Medical Journal of Australia. 2004 Oct 4;181(7):357–60. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parr JM, Pinto N, Hanson M, Meehan A, Moore PT. Medical Graduates, Tertiary Hospitals, and Burnout: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Ochsner J. 2016;16(1):22–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Topping K, Ehly S. In: Peer Assisted Learning. 1st ed. Topping K, Ehly S, editors. Vol. 1. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tai J, Molloy E, Haines T, Canny B. Same-level peer-assisted learning in medical clinical placements: a narrative systematic review. Med Educ. 2016 Apr;50(4):469–84. doi: 10.1111/medu.12898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamachi S, Giles JA, Dornan T, Hill EJR. “You understand that whole big situation they’re in”: interpretative phenomenological analysis of peer-assisted learning. BMC Med Educ. 2018 Dec 14;18(1):197. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1291-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lockspeiser TM, O’Sullivan P, Teherani A, Muller J. Understanding the experience of being taught by peers: the value of social and cognitive congruence. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2008 Aug 24;13(3):361–72. doi: 10.1007/s10459-006-9049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cate O, Durning S. Dimensions and psychology of peer teaching in medical education. Med Teach. 2007 Jan 3;29(6):546–52. doi: 10.1080/01421590701583816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt HG, Moust JH. What makes a tutor effective? A structural-equations modeling approach to learning in problem-based curricula. Academic Medicine. 1995 Aug;70(8):708–14. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199508000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]