Abstract

Objectives:

The work system reform and the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan have prompted efforts toward telecommuting in Japan. However, only a few studies have investigated the stress and health effects of telecommuting. Therefore, this study aimed to clarify the relationship between telecommuting and job stress among Japanese workers.

Material and Methods:

This was a cross-sectional study. In December 2020, during the “third wave” of the COVID-19 pandemic, an Internet-based nationwide health survey of 33 087 Japanese workers (The Collaborative Online Research on Novel-coronavirus and Work, CORoNaWork study) was conducted. Data of 27 036 individuals were included after excluding 6051 invalid responses. The authors analyzed a sample of 13 468 office workers from this database. The participants were classified into 4 groups according to their telecommuting frequency, while comparing scores on the subscale of the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) and subjective job stress between the high-frequency, medium-frequency, low-frequency, and non-telecommuters groups. A linear mixed model and an ordinal logistic regression analysis were used.

Results:

A significant difference in the job control scores of the JCQ among the 4 groups was found, after adjusting for multiple confounding factors. The high-frequency telecommuters group had the highest job control score. Further, after adjusting for multiple confounding factors, the subjective job stress scores of the high- and medium-frequency telecommuters groups were significantly lower than those of the non-telecommuters group.

Conclusions:

This study revealed that high-frequency telecommuting was associated with high job control and low subjective job stress. The widespread adoption of telecommuting as a countermeasure to the public health challenges associated with the COVID-19 pandemic may also have a positive impact on job stress. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2022;35(3):339 – 51

Keywords: occupational health, job stress, office worker, COVID-19, telecommuting, job content questionnaire

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in the latter half of 2019 reached pandemic proportions in early 2020, after which it was declared a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern” by the World Health Organization (WHO) in January 2020 [1,2]. The global COVID-19 pandemic continues to have a significant socioeconomic impact, especially in daily life, work, and medical care worldwide, including in Japan [3–5].

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant influence on the work environment and practices, thus resulting in changes in work systems and management. These changes include restrictions on business trips and outings, physical distancing, and the digitization of customer relations [6–8]. In particular, telecommuting has been widely promoted as a countermeasure against emerging contagious diseases, including the COVID-19 infection [9,10]. According to a survey of approx. 20 000 people in Japan in November 2020, the national average rate of telecommuting among regular employees was 24.7% [11].

While the concept of telecommuting emerged in the 1970s, current innovations in information and communication technology (ICT) have transformed the work system, as many workers can work from remote locations [12]. In Japan, telecommuting or remote work using ICTs has been promoted to enable varied and flexible work arrangements according to individual workers’ circumstances through the work system reform. Physical workspaces and telecommuting differ in their physical and psychosocial working conditions. In addition, since telecommuting makes it difficult to collect the information necessary for labor management, it might be difficult to assess employees’ overwork load or health problems. Hence, it is important to investigate the effect of telecommuting on the physical and mental health of workers.

Several studies have investigated the health effects of telecommuting. Henke et al. [13] reported that telecommuting might reduce various health risks such as alcohol abuse, tobacco use, and obesity; however, telecommuting health risks varied by telecommuting intensity. Further, participants who telecommuted for ≤8 h/month were significantly less likely to experience depression, compared with nontelecommuters. Nijp et al. [14] reported that working from different workplaces (e.g., flexible office, home, or other remote locations) did not affect the control of working hours or the main psychosocial job factors such as job demands, job control, and social support; nevertheless, a decline in health status was observed. Moreover, while there have been studies on the influence of telecommuting on mental health, their results are inconclusive, as they may report negative or positive effects depending on various confounding factors and moderators [15–18]. Nevertheless, telecommuting during a communicable disease pandemic can eliminate the risk of infection at the workplace. Therefore, allowing remote work could possibly enhance a sense of security and improve employee mental health. Changes in work systems arrangement, in combination with the COVID-19 pandemic will stimulate efforts toward telecommuting. Therefore, recognizing the impact of changes in the work system on workers’ health is crucial. However, there has been little research on the health and mental health effects of telecommuting, as well as on the impact of telecommuting on employees’ psychological job demands, job control, mental health, and social support. Moreover, it is especially relevant to assess this impact during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Therefore, this study aims to clarify the relationship between telecommuting and job stress among Japanese workers. The telecommuting frequency has increased temporally owing to the COVID-19 pandemic; thus, this study particularly focuses on the telecommuting frequency during this time. The authors analyzed the relationship between the telecommuting frequency and job stressors, as well as that between the frequency of telecommuting and subjective job stress. The authors believe that this study will provide evidence on the issues and coping mechanisms for job stress among telecommuters during the COVID-19 pandemic.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study design and setting

The Collaborative Online Research on Novel-coronavirus and Work (CORoNaWork) study is a prospective cohort study by a research group from the University of Occupational and Environmental Health. This study uses self-administered questionnaire surveys disseminated through a Japanese Internet survey company (Cross Marketing Inc., Tokyo, Japan); the baseline survey was conducted December 22–25, 2020. The follow-up survey will be conducted as a cohort study with the same participants. Incidentally, during the baseline survey, the number of COVID-19 infections and deaths were overwhelmingly high, compared with those in the first and second waves; therefore, Japan was on maximum alert during the third wave. This study adopted a cross-sectional design using a part of the data from the baseline survey of the CORoNaWork study. The details of the study protocol have been reported in another study [19].

Participants

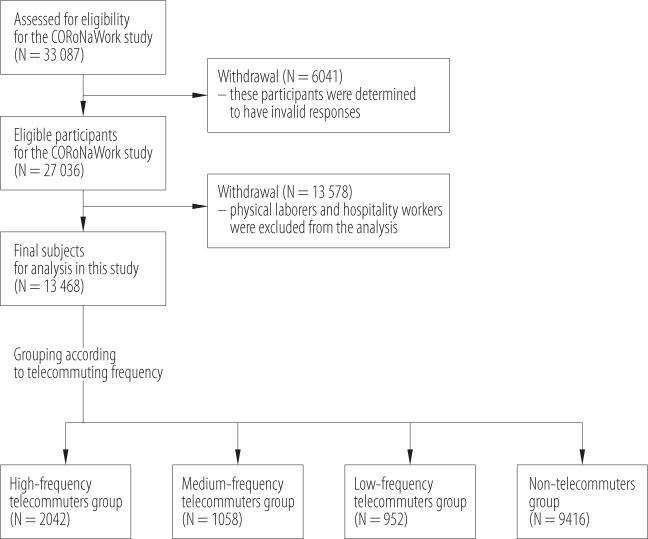

A total of 33 087 participants, who were stratified by cluster sampling by gender, age, region, and occupation, participated in the CORoNaWork study. The age of the survey participants ranged 20–65 years, and all participants were working at the time of the baseline survey. A database of 27 036 individuals was created by excluding 6051 invalid responses. The data of 13 468 office workers was analyzed.

Six thousand six hundred forty-one physical workers and 6927 hospitality workers, whose jobs require mental labor, were excluded because the authors posited that it could be difficult for them to telecommute for work. Regarding the characteristics of the excluded participants who were physical workers, a majority of participants worked in the food industry and automobile manufacturing industry. Regarding the characteristics of the excluded participants who were hospitality workers, many participants worked in the retail trade (e.g., apparel, accessory, or cosmetic store, and eating and drinking places, and health services). In addition, 1740 of 6927 participants were freelancers. Thus, the proportion of freelancers was higher than that of office workers (1257 out of 13 468). Considering the professional background of physical workers and hospitality workers, the authors considered it inappropriate to include them in the analysis of this study.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire items used in this study have been described in detail [19]. The authors used the data on sex, age, educational background, area of participants’ residence, job type, participants’ company size, working hours (per day), family structure, telecommuting frequency, including work-related questionnaire items from the Japanese version of the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) [20,21] as well as subjective job stress scores.

The original question on the telecommuting frequency was: “Have you telecommuted? Please choose the answer that is closest to your current situation.” Participants responded to this question on a 5-item ordinal scale comprising the following alternatives: ≥4 days/week, 2–3 days/week, 1 day/week, 1–3 days/month, never. The original question on the subjective job stress scale was: “How has your job stress changed after the COVID-19 outbreak? Please choose the answer that best applies to your current situation.” Participants were required to respond using a 3-point Likert scale with the following alternatives: “increased,” “stayed the same,” “decreased.”

The JCQ developed by Karasek is based on the job demands–control (or demand–control–support) model [20]. The reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the JCQ have been demonstrated by Kawakami et al. [21]. The authors used a shortened version of the 22 items in the JCQ, in which each item was rated on a 4-point scale (1 – strongly disagree, 4 – strongly agree). The JCQ includes a 5-item job demands scales (score range: 12–48, Cronbach’s α in the present sample = 0.63), a 9-item job control scale (score range: 24–96, Cronbach’s α in the present sample = 0.74), a 4-item supervisor support scale (score range: 4–12, Cronbach’s α in the present sample = 0.94), and a 4-item co-worker support scale (score range: 4–12, Cronbach’s α in the present sample = 0.90).

Variables

Outcome variables

The scores for job demands, job control, supervisor support, and co-worker support from JCQ, and the change in the subjective job stress score (1 – decreased, 2 – stayed the same, 3 – increased) were used as outcome variables.

Predictor variable

The authors classified the participants into 4 groups according to telecommuting frequency: high-frequency telecommuters group for participants telecommuting for ≥4 days/week; medium-frequency, for those telecommuting for 2–3 days/week; low-frequency, for those telecommuting for ≤1 day/week; and non-telecommuters group, for those who did not telecommute. These variables were used as the predictor variables.

Potential confounders

The following items, surveyed using a questionnaire, were used as confounding factors:

personal characteristics: sex, age, education (i.e., junior or senior high school, junior college or vocational school, university, or graduate school);.

work-related factors: occupation (i.e., regular employees, managers, executives, public service worker, temporary workers, freelancers or professionals, and others), participants’ company size (i.e., ≤9, 10–49, 50–99, 100–499, 500–999, 1000–9999, ≥10 000 employees), working hours (per day) (i.e., <8, ≥8 and <9, ≥9 and <11, ≥11);

familial factors: marital status (i.e., married, unmarried), living with family (presence or absence). Additionally, the prefecture of participants’ residence was used as another variable.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan (reference numbers: R2-079 and R3-006). Participants’ informed consent was obtained through a form on a website.

Statistical analyses

Linear mixed model (LMM) was used to analyze the relationships between the 4 telecommuting frequency groups and the subscales of the JCQ. At this stage, the dependent variables consisted of the scores of job demand, job control, co-worker support, and supervisor support of JCQ, after which the following 3 models were analyzed. In Model 1, the authors treated the 4 classifications of telecommuting frequency as fixed effects, whereas the prefecture of residence as random effects. In Model 2, the authors added the variables of sex, age, and education to the fixed effects of Model 1. In Model 3, the authors added the variables of occupation, participants’ company size, working hours, marital status, and living with family, to the fixed effects of Model 2. The estimated marginal means (EMM) of the subscale by 4 groups of telecommuting frequency were calculated by adjusting for the dependent variable in each model of LMM. Residual maximum likelihood (REML) estimation was used for estimations for fixed effects in LMM, whereas Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) was used to determine the goodness of fit of the statistical model.

An ordinal logistic regression analysis (OLR) was employed to analyze 4 classifications of telecommuting frequency, as well as the changes in subjective job stress scores. The dependent variable consisted of the change in subjective job stress score, after which the following 3 models were analyzed. In Model 1, as a crude analysis, the authors treated the 4 classifications of telecommuting frequency as the independent variable. In Model 2, the authors adjusted for sex, age, and education. In Model 3, the authors adjusted for sex, age, education, occupation, participants’ company size, working hours, marital status, and living with family. Cox and Snell R-squared was used to determine the goodness of fit of the statistical model. In all tests, the threshold for significance was set at p < 0.05. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) v. 25.0 J analytical software was used for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Participants and descriptive data

There were 2042 participants in the high-frequency telecommuters group, 1058 in the medium-frequency telecommuters group, 952 in the low-frequency telecommuters group, and 9416 in the non-telecommuters group (Figure 1). Table 1 shows the participant characteristics by the telecommuting frequency groups. Male participants telecommuted more than female participants. The workers aged ≥50 were more likely to telecommute often. Regarding work-related factors, the proportion of those who worked at companies with ≤9 employees and those who worked <8 h/day was high in the high-frequency telecommuters group. Regarding familial factors, the proportion of participants who were married as well as those who were living with their family was low in the high-frequency telecommuters group (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study population selection in the study conducted in the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Fukuoka, Japan, December, 2020

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics by telecommuting frequency groups in the study conducted in the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Fukuoka, Japan, December, 2020

| Variable | Participants (N = 13 468) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| total | telecommuting frequency | ||||

| high (N = 2042) | medium (N = 1058) | low (N = 952) | none (N = 9416) | ||

| Sex (male) [n (%)] | 6896 (51.2) | 1159 (56.8) | 591 (55.9) | 613 (64.4) | 4533 (48.1) |

| Age [n (%)] | |||||

| 20–29 years | 751 (5.6) | 81 (4.0) | 52 (4.9) | 54 (5.7) | 564 (6.0) |

| 30–39 years | 2227 (16.5) | 308 (15.1) | 170 (16.1) | 142 (14.9) | 1607 (17.1) |

| 40–49 years | 4080 (30.3) | 558 (27.3) | 292 (27.6) | 278 (29.2) | 2952 (31.4) |

| 50–59 years | 4682 (34.8) | 765 (37.5) | 383 (36.2) | 345 (36.2) | 3189 (33.9) |

| ≥60 years | 1728 (12.8) | 330 (16.2) | 161 (15.2) | 133 (14.0) | 1104 (11.7) |

| Education [n (%)] | |||||

| junior or senior high school | 3018 (22.4) | 366 (17.9) | 119 (11.2) | 132 (13.9) | 2401 (25.5) |

| junior college or vocational school | 2780 (20.6) | 433 (21.2) | 163 (15.4) | 138 (14.5) | 2046 (21.7) |

| university or graduate school | 7670 (56.9) | 1243 (60.9) | 776 (73.3) | 682 (71.6) | 4969 (52.8) |

| Occupation [n (%)] | |||||

| regular employees | 6483 (48.1) | 647 (31.7) | 522 (49.3) | 434 (45.6) | 4880 (51.8) |

| managers | 1743 (12.9) | 173 (8.5) | 199 (18.8) | 225 (23.6) | 1146 (12.2) |

| executives | 545 (4.0) | 96 (4.7) | 53 (5.0) | 52 (5.5) | 344 (3.7) |

| public service worker | 1758 (13.1) | 25 (1.2) | 58 (5.5) | 107 (11.2) | 1568 (16.7) |

| temporary workers | 1411 (10.5) | 157 (7.7) | 108 (10.2) | 75 (7.9) | 1071 (11.4) |

| freelancers or professionals | 1257 (9.3) | 756 (37.0) | 96 (9.1) | 45 (4.7) | 360 (3.8) |

| others | 271 (2.0) | 188 (9.2) | 22 (2.1) | 14 (1.5) | 47 (0.5) |

| Company size [n (%)] | |||||

| ≤9 employees | 2732 (20.3) | 1100 (53.9) | 174 (16.4) | 110 (11.6) | 1348 (14.3) |

| 10–49 employees | 2009 (14.9) | 109 (5.3) | 98 (9.3) | 90 (9.5) | 1712 (18.2) |

| 50–99 employees | 1164 (8.6) | 69 (3.4) | 70 (6.6) | 65 (6.8) | 960 (10.2) |

| 100–499 employees | 2543 (18.9) | 160 (7.8) | 167 (15.8) | 164 (17.2) | 2052 (21.8) |

| 500–999 employees | 1038 (7.7) | 98 (4.8) | 94 (8.9) | 96 (10.1) | 750 (8.0) |

| 1000–9999 employees | 2767 (20.5) | 306 (15.0) | 274 (25.9) | 263 (27.6) | 1924 (20.4) |

| ≥10 000 employees | 1215 (9.0) | 200 (9.8) | 181 (17.1) | 164 (17.2) | 670 (7.1) |

| Working time [n (%)] | |||||

| <8 h/day | 2658 (19.7) | 723 (35.4) | 233 (22.0) | 164 (17.2) | 1538 (16.3) |

| 8 – <9 h/day | 7769 (57.7) | 904 (44.3) | 558 (52.7) | 509 (53.5) | 5798 (61.6) |

| 9 – <11 h/day | 2583 (19.2) | 341 (16.7) | 237 (22.4) | 241 (25.3) | 1764 (18.7) |

| ≥11 h/day | 458 (3.4) | 74 (3.6) | 30 (2.8) | 38 (4.0) | 316 (3.4) |

| Marriage status (married) [n (%)] | 7764 (57.6) | 991 (48.5) | 650 (61.4) | 625 (65.7) | 5498 (58.4) |

| Presence of family living together [n (%)] | 10 642 (79.0) | 1512 (74.0) | 828 (78.3) | 770 (80.9) | 7532 (80.0) |

| Job Contents Questionnaire subscales (M±SD) | |||||

| Job demands | 29.2±5.9 | 28.3±5.9 | 29.3±5.7 | 29.6±5.8 | 29.4±5.9 |

| Job control | 64.0±11.1 | 68.4±11.5 | 65.9±10.6 | 66.0±10.2 | 62.6±10.8 |

| Supervisor support | 10.1±3.0 | 9.8±3.5 | 10.3±2.8 | 10.4±2.7 | 10.0±2.9 |

| Co-worker support | 10.4±2.6 | 10.1±3.2 | 10.6±2.4 | 10.7±2.3 | 10.4±2.5 |

| Score distribution of the change in subjective | |||||

| job stress [n (%)] | |||||

| decreased | 582 (4.3) | 204 (10.0) | 121 (11.4) | 46 (4.8) | 211 (2.2) |

| stayed the same | 9396 (69.8) | 1435 (70.3) | 659 (62.3) | 661 (69.4) | 6641 (70.5) |

| increased | 3490 (25.9) | 403 (19.7) | 278 (26.3) | 245 (25.7) | 2564 (27.2) |

The groups according to telecommuting frequency are: high – high-frequency telecommuters group, medium – medium-frequency, low – low-frequency, none – non-telecommuters group.

The subscales of the Job Content Questionnaire among the telecommuting frequency groups

The high-frequency telecommuters group had the lowest, whereas the low-frequency telecommuters group had the highest mean scores for job demands, supervisor support, and co-worker support among the 4 groups. Moreover, the high-frequency telecommuters group as well as the low-frequency telecommuters group had the highest mean score for job control (Table 1).

The authors compared the scores of each subscale of the JCQ among the 4 telecommuting frequency groups using LMM (Models 1–3) (Table 2). In each of the 4 subscales of the JCQ, the fit of the statistical model as determined by AIC was the best for Model 3 and the worst for Model 1. The job demands score of the high-frequency telecommuters group was significantly lower than that of the non-telecommuters group (reference) in Models 1 and 2. However, there was no significant difference between the 2 groups in Model 3. In Model 3, the main effect tests for all 3 confounders of work-related factors were significant, whereas those of familial factors were not significant. The score of job demand was likely to be lower in cases where the company size was smaller and the working hours were lower. The job control scores of the high-, medium- and lowfrequency telecommuters groups were significantly higher than those of the non-telecommuters group in all the models.

Table 2.

Comparison of the scores of subscales of the Job Contents Questionnaire by telecommuting frequency groups in the study conducted in the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Fukuoka, Japan, December, 2020

| Job Contents Questionnaire subscale | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| coefficient | 95% CI | p | coefficient | 95% CI | p | coefficient | 95% CI | p | |

| Job demands | |||||||||

| high | –1.11 | –1.39–(–0.82) | <0.001 | –1.11 | –1.39–(–0.82) | <0.001 | –0.28 | –0.60–0.03 | 0.080 |

| medium | –0.08 | –0.46–0.30 | 0.670 | –0.17 | –0.55–0.20 | 0.364 | –0.13 | –0.49–0.24 | 0.497 |

| low | 0.21 | –0.19–0.60 | 0.298 | 0.00 | –0.39–0.39 | 0.998 | –0.15 | –0.53–0.24 | 0.456 |

| Job control | |||||||||

| high | 5.97 | 5.44–6.50 | <0.001 | 5.44 | 4.92–5.95 | <0.001 | 3.65 | 3.07–4.22 | <0.001 |

| medium | 3.53 | 2.83–4.24 | <0.001 | 3.00 | 2.32–3.69 | <0.001 | 2.52 | 1.85–3.20 | <0.001 |

| low | 3.56 | 2.84–4.29 | <0.001 | 2.80 | 2.09–3.51 | <0.001 | 2.31 | 1.61–3.00 | <0.001 |

| Supervisor support | |||||||||

| high | –0.21 | –0.36–(–0.07) | 0.003 | –0.26 | –0.4–(–0.11) | <0.001 | 0.12 | –0.04–0.28 | 0.151 |

| medium | 0.29 | 0.10–0.48 | 0.002 | 0.21 | 0.02–0.40 | 0.032 | 0.22 | 0.02–0.41 | 0.027 |

| low | 0.40 | 0.20–0.6 | <0.001 | 0.33 | 0.13–0.53 | 0.001 | 0.27 | 0.07–0.47 | 0.008 |

| Co-worker support | |||||||||

| high | –0.29 | –0.41–(–0.17) | <0.001 | –0.32 | –0.45–(–0.20) | <0.001 | –0.04 | –0.19–0.10 | 0.559 |

| medium | 0.17 | 0.00–0.33 | 0.048 | 0.10 | –0.06–0.27 | 0.222 | 0.10 | –0.07–0.27 | 0.246 |

| low | 0.33 | 0.15–0.50 | <0.001 | 0.27 | 0.10–0.45 | 0.002 | 0.21 | 0.04–0.39 | 0.016 |

The groups as explained in Table 1. The authors statistically compared non-telecommuters group (none) as reference with the other three groups for each parameters.

The model 1 was a crude analysis.

The model 2 was adjusted for sex, age, and education.

The model 3 was adjusted for sex, age, education, occupation, participants’ company size, working hours, marital status, and living with family.

The supervisor support scores of the medium- and lowfrequency telecommuters groups were significantly higher, whereas the scores of the high-frequency telecommuters group were significantly lower than those of the non-telecommuters group in Models 1 and 2; however, no significant difference was found in Model 3. The scores of co-worker support of the medium- and low-frequency telecommuters groups were significantly higher, whereas the scores of co-worker support of the high-frequency telecommuters group were significantly lower than those of the non-telecommuters group in Models 1. However, there was no significant difference between the medium-telecommuters groups and the non-telecommuters group in Model 2. No significant differences were found between the high-telecommuters groups and the nontelecommuters group, as well as the medium-frequency telecommuters groups and the non-telecommuters group in Model 3. In Model 3 of supervisor and co-worker support, the main effect tests for all confounders of workrelated and familial factors were significant. The scores of supervisor and co-worker support were likely to be lower in cases of small company size, long working hours, as well as for participants who were unmarried, or were not living with family.

Change in the subjective job stress scores among the telecommuting frequency groups

The non-telecommuters group demonstrated the highest, whereas the high-frequency telecommuters group had the lowest increase in subjective job stress scores among the 4 groups. Furthermore, the medium-frequency telecommuters group showed the highest, whereas the nonfrequency telecommuters group showed the lowest decrease in subjective job stress scores among the 4 groups (Table 1).

The authors compared the scores of increase and decrease in subjective job stress among the 4 groups using OLR (Models 1–3) (Table 3). The fit of a statistical model as determined by Cox and Snell R-squared model was the best in Model 3 and the worst in Model 1. In all models, the subjective job stress score of the high- and medium-frequency telecommuters groups was significantly lower than that of the non-telecommuters group (reference). Regarding the confounders in Model 3, the subjective job stress scores of the “<8 h/day” and “≥8 h/day” and “<9 h/day” groups were significantly lower, compared with those of the “≥11 h/day” group as reference (odds ratio (OR) = 0.51, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.41–0.64, OR = 0.61 95% CI: 0.50–0.75). Moreover, the subjective job stress score of the married group was significantly lower than that of the unmarried group (OR = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.74–0.90).

Table 3.

Comparison of the change in subjective job stress scores by telecommuting frequency groups in the study conducted in the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Fukuoka, Japan, December, 2020

DISCUSSION

This study clarified the relationship between job stress and telecommuting frequency. First, the authors considered the relationships between job demands and control and telecommuting frequency. When adjusted only for residence and personal characteristics, high-frequency telecommuters had significantly lower job demands, compared with the other groups. However, after adjusting for work-related and familial factors, the authors observed no significant difference between job demands and telecommuting frequency. The authors suggest that job demand is strongly influenced by work-related factors rather than by the implementation of telecommuting, based on the analysis of confounding factors. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, previous studies suggest that telecommuting may increase working hours [22], and appropriate working time management under telecommuting is crucial to enable coping with job stress.

Job control was higher for high-frequency telecommuters, even after adjusting for residence, personal characteristics, and work-related and familial factors. The authors believe that this finding is important. Previously, it was believed that most workers who can telecommute could be employed in specific job positions or occupations, where they were able to decide their work contents or had the authority to determine their own work hours (such as flexible work hours). Nevertheless, to control the current COVID-19 pandemic, many workers have been able to telecommute due to restrictions imposed by the Japanese government. Despite the ad hoc telecommuting measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is possible that it has had a positive influence, resulting in improved job control and reduced job stress owing to arrangements to make telecommuting easier for employees.

Next, after adjusting for residence and personal characteristics, high-frequency telecommuters had significantly lower supervisor and co-worker support, compared with the other groups. However, after adjusting for work-related and familial factors, no significant differences by telecommuting frequency were observed. Further, the analysis of confounders showed that these results were influenced by both work-related and familial factors. The supervisor or co-worker support scores were likely to be higher for those who were married and living with family. Therefore, these familial factors might lead to poor communication and reduced social support scores. The psychological repercussions of balancing work and family life have long been proposed through the concept of “work-family conflict” [23]. The relationship between work and family has an important impact on job and life satisfaction. In particular, an appropriate assignment between an individual’s work and family roles increases job and family satisfaction [24].

Furthermore, telecommuting is shown to enhance work flexibility and time spent at home, which results in increased happiness and life satisfaction and decreased stress associated with work-life balance [25]. In particular, the authors believed that telecommuting under the current COVID-19 pandemic complemented social support in the workplace, owing to its positive psychological impact on family support, or coping behaviors related to work-family conflict.

As for work-related factors, the authors believe that largescale companies may find it easier to maintain social support, since they have a better consultation system or are able to provide various means of communication when telecommuting. It has been reported that high-quality communication, peer support, and networks within organizations could positively impact mental health, while strengthening social capital and organizational resilience during an infectious pandemic [26]. Thus, establishing an effective telecommuting network in the workplace is crucial.

After adjusting for residence, personal characteristics, and work-related and familial factors, the subjective job stress score of the high-frequency telecommuters and mediumfrequency telecommuters were significantly lower than that of non-telecommuters. Job stress was influenced by various factors; particularly, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic must also be considered in this study. During the COVID-19 pandemic, people were worried about getting infected in their daily lives and at the workplace. As COVID-19-related measures such as reduced working hours, safety protocols, and improved job support are associated with positive mental health, appropriate preventive measures could reduce psychological distress and protect work performance [27]. The authors speculated that the elimination of infection anxiety related to COVID-19 due to telecommuting is associated with a decrease in job stress, as the office workers analyzed in this study may be more susceptible to these factors.

Limitations

This study has 4 limitations. First, since the CORoNaWork study is an Internet-based survey including only workers residing in Japan, the generalizability of the results is uncertain. The authors attempted to reduce the bias of the participants as much as possible by sampling them by generation, residence, and occupation. However, there are country-wise differences in labor-related laws, regulations, and guidelines; further, systems and initiatives related to telecommuting as well as the status of the COVID-19 pandemic vary greatly, worldwide. Even though the aforementioned points restricted the generalizability of the study, future studies should report new findings on the health effects of telecommuting after the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors also intend to improve the validity of this findings through follow-up surveys over the next few years.

Second, since the present study adopted a cross-sectional design, the causal relationship between telecommuting and job stress is unknown. Telecommuting has been strongly recommended ever since the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic as a measure to prevent the spread of infection in the workplace [28]. Further, it continues to be in force even today. The authors conducted this study more than half a year ago, at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and thus, the authors believe that the context of the impact of telecommuting on job stress is reasonable.

Third, the authors assessed the degree of change in subjective job stress from the past to the present using a 3-point Likert scale. Therefore, the existence of a response bias cannot be denied. It is necessary to reconsider the questionnaire items and conduct a longitudinal evaluation.

Fourth, as this study assessed telecommuting during the COVID-19 pandemic, there may be some differences in the effects on job stress during normal telecommuting. However, the findings of this study were consistent with that of previous studies. Moreover, the authors adjusted for potential confounders to ensure a certain degree of rationality. Further research on telecommuting in Japan is required.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, the authors analyzed the relationship between job stress and telecommuting in Japanese workers during the COVID-19 pandemic using the CORoNaWork database. The authors found that high-frequency telecommuting was associated with high job control among the 4 job stressors including job demands, job control, supervisor support, and co-worker support. In addition, this study revealed an association between telecommuting frequency and subjective job stress. The authors suggest that high-frequency telecommuting during an infectious pandemic could be associated with low job stress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors appreciate all the participants and all members of the CORoNaWork Study Group. The current members of the CORoNaWork Project, in alphabetical order, are as follows: Dr. Yoshihisa Fujino (present chairperson of the study group), Dr. Akira Ogami, Dr. Arisa Harada, Dr. Ayako Hino, Dr. Hajime Ando, Dr. Hisashi Eguchi, Dr. Kazunori Ikegami, Dr. Kei Tokutsu, Dr. Keiji Muramatsu, Dr. Koji Mori, Dr. Kosuke Mafune, Dr. Kyoko Kitagawa, Dr. Masako Nagata, Dr. Mayumi Tsuji, Ms. Ning Liu, Dr. Rie Tanaka, Dr. Ryutaro Matsugaki, Dr. Seiichiro Tateishi, Dr. Shinya Matsuda, Dr. Tomohiro Ishimaru, and Dr. Tomohisa Nagata. All members are affiliated with the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan. The authors would also like to thank Editage for English language editing.

Footnotes

Funding: this study was supported by Anshin Zaidan (project entitled “A general incorporated foundation for the development of educational materials on mental health measures for managers at small-sized enterprises,” grant manager: Hisahsi Eguchi), by Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (grant No. H30-josei-ippan-002 entitled “Health, Labour and Welfare Sciences Research Grants, Comprehensive Research for Women's Healthcare,” grant manager: Naoko Arata), by Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (grant No. H30-roudou-ippan-007 entitled “Research for the establishment of an occupational health system in times of disaster,” grant manager: Seiichiro Tateishi), by the Collabo-health Study Group (project entitled “consigned research foundation,” project manager: Koji Mori), by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (project entitled “A scholarship donations,” grant manager: Shinya Matsuda), and by a research grant from the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huang X, Wei F, Hu L, Wen L, Chen K.. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of COVID-19. Arch Iran Med. 2020; 23(4): 268–71. 10.34172/aim.2020.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World health Organization [Internet]. Geneva: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic; 2020. [cited Jan 10 2021]. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19.

- 3.World Health Organization [Internet]. Geneva: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Weekly epidemiological update and weekly operational update: World Health Organization; 2019. [cited Dec 22 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novelcoronavirus-2019/situation-reports.

- 4.Jimi H, Hashimoto G.. Challenges of COVID-19 outbreak on the cruise ship Diamond Princess docked at Yokohama, Japan: a real-world story. Glob Health Med. 2020;2(2):63–5. 10.35772/ghm.2020.01038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kishimoto M, Ishikawa T, Odawara M.. Behavioral changes in patients with diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetol Int. 2020;12(2):241–45. 10.1007/s13340-020-00467-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dwivedi YK, Hughes DL, Coombs C, Constantiou I, Duan Y, Edwards JS, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on information management research and practice: transforming education, work and life. Int J Inf Manage. 2020;55:102211. 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alon TM, Doepke M, Olmstead-Rumsey J, Tertilt M.. The impact of COVID-19 on gender equality [Internet]. Massachusetts: National Bureau of economic research; 2020. [cited Dec 25 2020]. Available from: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w26947/w26947.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gursoy D, Chi CG.. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on hospitality industry: review of the current situations and a research agenda. J Hosp Mark Manag. 2020;29(5):527–9. 10.1080/19368623.2020.1788231. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belzunegui-Eraso A, Erro-Garcés A.. Teleworking in the context of the Covid-19 Crisis. Sustainability. 2020;12(9):3662. 10.3390/su12093662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan R, Javed Hasan S.. Telecommunting: The problems and challenges during Covid-19 (2020). Int J Eng Res. Technol. 2020; 9(7): 1027–33. 10.17577/IJERTV9IS070432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Persol Research and Consulting Co., Ltd. [Internet]. Tokyo: The fourth urgent survey on the impact of countermeasures against a new coronavirus on telework; 2020. [cited Apr 14 2021]. Available from: https://rc.persol-group.co.jp/thinktank/research/activity/data/telework-survey4.html.

- 12.International Labour Organization and the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound). [Internet]. Geneva and Dublin: Working anytime, anywhere: the effects on the world of work; 2017. [cited Dec 25 2020]. Available from: http://eurofound.link/ef1658.

- 13.Henke RM, Benevent R, Schulte P, Rinehart C, Crighton KA, Corcoran M.. The effects of telecommuting intensity on employee health. Am J Health Promot. 2016;30(8):604–12. 10.4278/ajhp.141027-QUAN-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nijp HH, Beckers DG, van de Voorde K, Geurts SA, Kompier MA.. Effects of new ways of working on work hours and work location, health and job-related outcomes. Chronobiol Int. 2016;33(6):604–18. 10.3109/07420528.2016.1167731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bentley T, Teo S, McLeod L, Tan F, Bosua R, Gloet M.. The role of organisational support in teleworker wellbeing: a sociotechnical systems approach. Appl Ergon. 2016;52:207–15. 10.1016/j.apergo.2015.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sardeshmukh SR, Sharma D, Golden TD.. Impact of telework on exhaustion and job engagement: a job demands and job resources model. New Technol Work Employ. 2012; 27(3): 193–207. 10.1111/j.1468-005X.2012.00284.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gajendran RS, Harrison DA.. The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(6):1524–41. 10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vander Elst T, Verhoogen R, Sercu M, Van den Broeck A, Baillien E, Godderis L.. Not extent of telecommuting, but job characteristics as proximal predictors of work-related wellbeing. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(10):e180-e6. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujino Y, Ishimaru T, Eguchi H, Tsuji M, Seichiro T, Ogami A, et al. Protocol for a nationwide Internet-based health survey in workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. J UOEH. 2021;43(2):217–25. 10.7888/juoeh.43.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karasek R. Job content questionnaire and users guide. Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts, Department of Work Environment; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawakami N, Kobayashi F, Araki S, Haratani T, Furui H.. Assessment of job stress dimensions based on the job demands-control model of employees of telecommunication and electric power companies in Japan: reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Job Content Questionnaire. Int J Behav Med. 1995;2(4):358–75. 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0204_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noonan MC, Glass JL.. The hard truth about telecommuting. Monthly Lab. Rev. 2012;135:38–45. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kahn RL, Wolfe DM, Quinn RP, Snoek JD, Rosenthal RA.. New York: Organizational stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams GA, King LA, King DW.. Relationships of job and family involvement, family social support, and work–family conflict with job and life satisfaction. J Appl Psychol. 1996; 81(4): 411. 10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minetaka K. Empirical research on the effects of telework and work flexibility on worker happiness, life satisfaction, work-family balance stress, and productivity. Joho Keiei. 2020;80:105–8. 10.20627/jsimconf.80.0_105. Japanese. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pollock A, Campbell P, Cheyne J, Cowie J, Davis B, McCallum J, et al. Interventions to support the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic: a mixed methods systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;11(11). 10.1002/14651858.CD013779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giorgi G, Lecca LI, Alessio F, Finstad GL, Bondanini G, Lulli LG, et al. COVID-19-related mental health effects in the workplace: a narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17(21): 7857. 10.3390/ijerph17217857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimizu K, Negita M.. Lessons learned from Japan’s response to the first wave of COVID-19: a content analysis. Healthcare (Basel). 2020;8(4):426. 10.3390/healthcare8040426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]