Abstract

Introduction

Pain self-management is crucial in reducing pain intensity and improving the quality of life for cancer patients. By acquiring self-management skills, patients can actively participate in managing their pain.

Objective

The objective of this study was to develop a grounded theory-based model to assist cancer patients in enhancing their pain self-management.

Methods

This qualitative research was conducted in two stages from 2019 to 2021. The initial phase utilized a grounded theory approach to explore the process of pain self-management in cancer patients. Following Corbin and Strauss’ analytical method, a grounded theory of pain management in cancer patients was identified. Subsequently, Walker and Avant’s theory synthesis strategy was employed to construct a practical model that provides support for patients in managing their pain.

Results

Within the conceptual framework, this study developed the “Holistic Supporting from Pain Self-Management” model. This supportive model consists of three main components: (1) enhancing pain self-management skills in cancer patients and their families, (2) empowering physicians and nurses in pain management for cancer patients, and (3) improving the organizational structure for pain management in cancer patients.

Conclusion

The Holistic Supporting from Pain Self-Management model emphasizes the importance of addressing all dimensions of cancer pain, including physical, functional, psychosocial, cultural, and spiritual aspects, to effectively manage pain in cancer patients. This model addresses the needs of patients, healthcare providers, and the healthcare system, aiming to enhance and support pain self-management.

Keywords: patient, cancer pain, self-management, model, holistic support

Introduction

Cancer represents a significant public health challenge in both developed and developing countries. In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) made an estimation that cancer ranks among the top two leading causes of death before the age of 70 in 112 out of 183 countries (WHO, 2020). The data reveals that there were more than 19.3 million newly diagnosed cancer cases worldwide, which subsequently led to approximately 10 million deaths in the year 2020 (Ferlay et al., 2021). Cancer pain is a prevalent and distressing symptom among individuals with malignant diseases, and it has a profound negative impact on the quality of life for both patients and caregivers (ElMokhallalati et al., 2018). An estimated one-third of patients do not receive pain medication that adequately matches the intensity of their pain, resulting in many patients experiencing inadequate pain management (Greco et al., 2014). The majority of patients can achieve effective pain relief if they receive appropriate treatment (Lou & Shang, 2017). However, pain is often undertreated due to various barriers at the institutional, professional, and patient levels (Orujlu et al., 2022). Self-management is essential for decreasing pain intensity and enhancing quality of life (ElMokhallalati et al., 2018). According to the definition of self-management of cancer pain, it is “the process by which patients with cancer pain decide to manage their pain, improve their self-efficacy by addressing issues caused by the pain, and integrate pain-relieving strategies into their daily lives, through interactions with healthcare professionals” (Yamanaka, 2018). Self-management of cancer pain involves a self-regulation approach that empowers patients in their pain management using the self-efficacy skills they have developed (Mertilus et al., 2021). The recent shift in healthcare policy toward providing care outside of the hospital and empowering patients to take control of their own disease has underscored the increasing importance of self-management (van Dongen et al., 2020). The process of self-management is dynamic in nature (Baker et al., 2014) and patients require professional support to effectively self-manage their condition and achieve their health goals (ElMokhallalati et al., 2018). Self-management support refers to any activity or strategy that assists individuals in effectively managing their disease and living well with it (Davies, 2019). The management of cancer pain poses challenges and relies on various factors related to patients, healthcare providers, and the healthcare system. Symptoms associated with cancer, including pain, need to be addressed within a chronic disease framework that empowers patients to self-manage their condition, cope with its effects, and navigate their emotional wellbeing (Luckett et al., 2019).

Review of Literature

We conducted a comprehensive analysis of prevailing theories pertaining to the enhancement of pain self-management, with a specific focus on cancer patients. The findings revealed a significant knowledge gap in this area. Previous theories were deemed inadequate for addressing the unique context of cancer pain and did not offer specific strategies for bolstering cancer patients’ self-management of pain. The existing theories in the field of pain treatment did not comprehensively incorporate the self-management component and the factors influencing cancer patients’ self-management activities. Considering the challenges patients face during the pain management process, it is evident that they require support. Moreover, an effective and relevant model should be rooted in the social and cultural contexts of the patients. In this regard, grounded theory is a suitable method for identifying and understanding these essential components within the broader framework of pain self-management (Corbin & Strauss, 2014). The theory derived from the grounded theory study is a descriptive theory and it is necessary to develop it in the form of a prescriptive theory or a clinical model, which is the operational and practical form of the theory. Therefore, the researcher for design a comprehensive supporting model from pain self-management of cancer patients, and in other words, to transform the descriptive theory into a prescriptive theory (operational model) used from the theory synthesis method of Walker and Avant to help patients and support them to improve pain self-management.

This study aims to develop a supporting model for improving cancer pain self-management based on the grounded theory study “doubtful persistent effort to pain relief” (Orujlu et al., 2021). This model, which includes well-known pain management strategies, can be utilized by patients and medical professionals to improve pain self-management in cancer patients so that effective pain management can be conducted.

Methods

This study was conducted in two phases. The first phase involved the use of grounded theory to thoroughly investigate the process of pain self-management among cancer patients. The findings from this phase were then utilized for theory construction in the second phase, following Walker and Avant's Strategy (Walker & Avant, 2011). The research was carried out at an oncology hospital from December 2020 to September 2021. This hospital is recognized as the largest cancer treatment center in northwestern Iran. The total sample size for the study consisted of 22 participants, including 17 patients, two caregivers, two nurses, and one physician. Caregivers were selected from the family members who had been involved in the long-term care of the patients and possessed substantial experience in managing the pain of these patients.

The study commenced with the application of purposive sampling, followed by the subsequent utilization of theoretical sampling methodology. The study utilized purposeful sampling to select an initial participant who had long-term, intense pain and a willingness to share experiences. Based on data from the initial interview, other participants with rich experience and valuable insights were chosen. The subsequent sample selection aimed to enhance the development of categories and concepts. The study used theoretical sampling based on the information obtained during the analysis process. The purpose was to gather additional data and bridge gaps in the emerging theory. In theoretical sampling, the selection of the next participant was determined by their potential to help clarify multiple categories. Consequently, further interviews were conducted with individuals who could provide valuable insights to enhance these aspects.

Data was obtained through several methods, including semistructured interviews, field notes, and a literature review. The average duration of interviews was approximately 35 min. The theoretical saturation of themes and the development of theory were utilized as sample saturation evaluation criteria. Interviews were recorded with a digital tape recorder. The research methodology utilized in this study followed the approach proposed by Corbin and Strauss, which involved simultaneous data collection and analysis (Corbin & Strauss, 2014). Thus, transcribed interviews were entered into MAXQDA1 software to identify relevant expressions of participants’ pain self-management experiences. To immerse in the data, each interview's transcript was read and re-read several times. Semantic coding and categorization were performed according to the similarities and differences of codes. The final analysis determined concepts, context, process, and consequences.

According to Walker and Avant, researchers and theorists are advised to adopt a theory synthesis approach when they have initial concepts and statements for theory development. Theory synthesis aims to construct a coherent and interconnected system of ideas by integrating evidence. In this strategy, the theorist gathers available information on a specific phenomenon and organizes concepts and statements into a cohesive network, resulting in a synthesized theory (Walker & Avant, 2011). In the present study, the researcher has already identified the main concepts and propositions pertaining to the self-management of pain in cancer patients, which were initially presented as a descriptive theory. To further develop this into a prescriptive model, the strategy of theory synthesis is being employed. The subsequent sections (“Specifying Focal Concepts to Serve as Anchors for the Synthesized Theory”; “Reviewing the Literature to Identify Factors Related to the Focal Concepts and to Specify the Nature of Relationships”; and “Organizing Concepts and Statements into an Integrated and Efficient Representation of the Phenomena of Interest” ) outline the process of specifying focal concepts, reviewing the literature, and organizing concepts and statements into an integrated representation of the phenomena of interest.

Specifying Focal Concepts to Serve as Anchors for the Synthesized Theory

The focal concept of this theory was selected based on the key findings from the grounded theory study. The researchers developed a middle-level theory known as “doubtful persistent effort to pain relief” through the process of grounded theory research. The main concern identified in the grounded theory was “persistent pain suffering,” indicating that patients consistently made uncertain or doubtful efforts to manage their pain. The study found that various contextual factors influenced how patients self-managed their pain. However, due to the lack of effective strategies, individuals often experienced mood disorders, feelings of worthlessness, and life turmoil (Orujlu et al., 2021). Therefore, the “holistic supporting for pain self-management (HSPS) model” serves as the focal concept for the supporting model in the self-management process of cancer pain. Holistic pain self-management support covers all levels of the patient, healthcare providers, and healthcare system, as well as highlights the importance of giving special attention to every aspect of cancer pain. Based on the grounded theory study, the main hypothesis or statement was derived.

Since the world view in nursing has positively influenced the practice of nursing in accordance with the four fundamental metaparadigm concepts in nursing, namely “person,” “environment,” “nursing,” and “health,” the focal concept of holistic supporting for pain self-management alongside metaparadigm concepts has been considered as the primary conceptual framework of this model.

Reviewing the Literature to Identify Factors Related to the Focal Concepts and to Specify the Nature of Relationships

The second step in the process of theory synthesis involves conducting a thorough search and review of published literature related to the focal concepts with the assistance of the framework. In this study, the researcher conducted a comprehensive analysis of the current published literature on the central concept, “the HSPS,” and its associated factors. The research team members systematically reviewed all relevant documents, identified pertinent statements, and extracted concepts. Following the guidelines provided by Walker and Avant, the data obtained from the literature review were interpreted and transformed into logical statements. Comparable concepts were categorized and simplified to enhance clarity and cohesiveness. This process allowed for a more comprehensive understanding of the relevant concepts and their relationships within the HSPS model.

Organizing Concepts and Statements Into an Integrated and Efficient Representation of the Phenomena of Interest

When a theorist has gathered a reasonably comprehensive list of relational statements related to one or more focal concepts, these statements can be organized into a coherent pattern of relationships among variables. This pattern of relationships can then be presented as an explanatory diagram or explanation (Walker & Avant, 2011). In the Results section of the study, the well-organized structural components of the model, including assumptions, concepts, and objectives are described in detail.

Rigor

Throughout the study, the researchers followed the rigor criteria for qualitative research proposed by Lincoln and Guba (1985). The researchers made deliberate efforts to establish and maintain a consistent connection with the research topic, participants, and data. They employed investigator triangulation to provide confirmation and additional perspectives on the findings. Each interview was given sufficient time, and the codes were continuously compared to identify similarities and differences. The results were re-checked with the participants. The readers were presented with a comprehensive data analysis and provided with deep and rich explanations of the research. The research team members’ corrective remarks about the interview procedure, analysis, and data extraction were taken into account.

Ethical Consideration

The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee. Prior to each interview, participants were provided with comprehensive information regarding the study’s objectives, interview procedures, their right to participate, and the confidentiality of their information. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before conducting the interviews.

Results

There were 11 female patients ranging in the age from 21 to 55, with a mean age of 37.96 ± 9.57. The qualitative analysis of interview and field notes revealed 1860 initial codes, 14 subcategories, and four main categories.

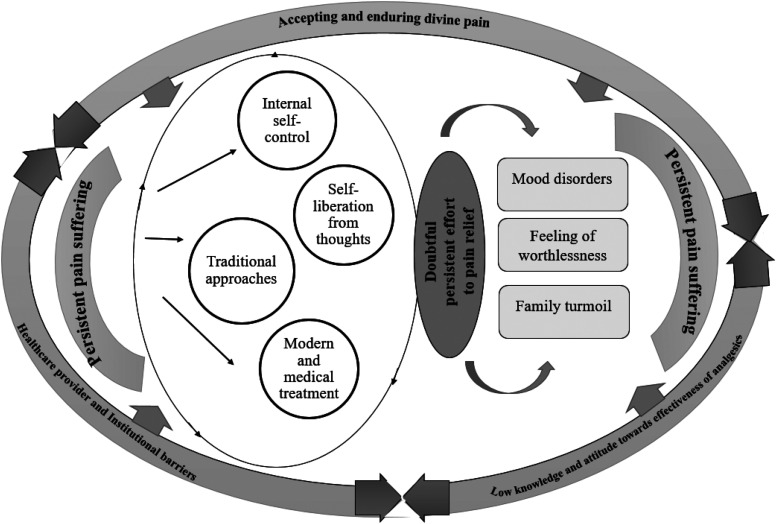

The subcategories included “sensory perceptions of pain,” “multiple pain generators,” “barriers to pain relief,” “internal self-control,” “self-liberation from negative spontaneous thoughts,” “traditional approaches,” “medical treatment,” “mood disorders,” “feelings of worthlessness,” and “life turmoil.” The participants expressed “persistent pain suffering” as the main concern, and the core concept that emerged from the developed grounded theory was “doubtful persistent effort to pain relief” (Table 1). The researchers followed a systematic approach to identify the core category, which serves as a comprehensive and abstract concept summarizing the main ideas expressed by writing the story line and reviewing memories. This core category, also known as the central category, represents the primary theme of the research. It was carefully selected to encompass all participants and demonstrate the highest explanatory power, connecting the other categories to it and establishing relationships among them. The researchers ensured that the core category met several criteria: being abstract enough to serve as the overarching explanatory concept, be consistently indicated throughout the data, align logically with the findings, and gain depth and explanatory power through its relationships with other categories (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Major Themes and Main Categories Derived From the Data.

| Major themes | Category |

|---|---|

| Persistent pain suffering (main concern) |

Sensory perceptions of pain Multiple pain generators |

| Doubtful persistent effort to pain relief (core variable) |

Internal self-control Self-liberation from negative spontaneous thoughts Traditional approaches affected by others Medical treatment |

| Barriers to pain relief (context) |

Accepting and enduring divine pain Negative attitudes toward effectiveness of analgesics Patients’ low knowledge of pain self-management methods Healthcare provider as a barrier Institutional barriers |

| Negative influences of pain on patient and his/ her family (consequences) |

Mood disorders Feeling of worthlessness Family turmoil |

Figure 1.

Proposed diagram of pain self-management process in cancer patients.

The study successfully achieved its ultimate goal by analyzing the findings of the first stage using Walker and Avant's method. The core category and grounded theory identified in the first stage, “doubtful persistent effort to pain relief,” led to the selection of the “HSPS” model as the core concept for the second stage (Orujlu et al., 2022). The findings were presented within the context of an integrated care model/theory, based on relevant research within the conceptual framework and its organization. Two theories that were utilized in the development of the “HSPS” model, and from which relevant statements and concepts were extracted, are as follows:

5A's Behavior Change Model (Adapted for Self-Management Support Improvement)

Glasgow and Whitlock (2002) introduced the 5A Behavior Change Model as an evidence-based approach to improve self-management support across various behaviors and health issues. This model consists of five stages:

Assess: This stage involves assessing the patient's beliefs, behavior, and knowledge related to the targeted behavior or health issue.

Advise: Healthcare providers provide specific information about the health risks and benefits associated with changing the behavior.

Agree: Collaboratively, healthcare providers and patients set goals based on the patient's interests and confidence in their ability to change the behavior.

Assist: Healthcare providers help patients identify personal barriers, develop strategies, utilize problem-solving techniques, and establish social and environmental support.

Arrange: Healthcare providers work with patients to specify a plan for follow-up and ongoing support (Glasgow & Whitlock, 2002).

The 5A Behavior Change Model can be used to assess a cancer patient's behavior, knowledge, and beliefs. It enables healthcare providers to gain valuable insights into patients’ beliefs about cancer pain, their attitudes toward analgesics and opioids, and their level of knowledge and ability to employ pain management strategies. The model facilitates the provision of personalized recommendations and counseling based on the individual needs of the patients. Collaboratively, goals for pain management are agreed upon with the patients. Through this process, barriers that hinder successful pain management are identified, and appropriate actions are taken to address and overcome them. Regular follow-up appointments are scheduled to ensure ongoing support and to enhance patients’ understanding of the pain management process. By implementing this model, patients are educated about the significance and benefits of behavior adjustment in pain self-management. They also gain an understanding of the potential consequences of inadequate self-management. The model involves comprehensive planning with the patients, addressing and removing barriers that impede effective self-management, and offering continuous follow-up services. Overall, this approach provides a solid foundation for constructing a holistic supporting model for cancer pain self-management. It encompasses the assessment of patient needs, collaborative goal setting, barrier identification and resolution, patient education, and sustained follow up, all of which are essential components in facilitating effective pain self-management among cancer patients.

WISE self-management support model (Whole System Informing Self-management Engagement)

The WISE model is an evidence-based intervention designed to promote and facilitate the implementation of self-management support within a healthcare system. It recognizes the importance of understanding how healthcare professionals and patients respond to long-term conditions and aims to integrate patients, practitioners, and the service organization through a systematic approach. By implementing the WISE method, patients have the opportunity to receive more information and support with the help of healthcare professionals. The approach acknowledges the need for a shift in the roles and responsibilities of both medical staff and patients. It emphasizes the importance of reforming physicians’ and patients’ roles, providing them with more options, control, and resources to enhance patient communication and involvement in their care. Self-management programs enhance patients’ behavior by emphasizing the collaborative involvement of each level in the development and sustenance of self-management activities. The optimal effectiveness of this strategy is achieved when all levels actively intervene (Kennedy et al., 2007, 2010).

The current study highlighted barriers to successful pain management in cancer patients, including those related to patients, healthcare providers, and the healthcare system (Orujlu et al., 2022). It suggested that addressing pain treatment requires a holistic approach that considers patient engagement, healthcare provider involvement, and organizational support. This approach can be used to develop a holistic supporting model for pain self-management in patients. In the WISE model, patients are encouraged to select self-management support based on their abilities, needs, goals, and priorities. Healthcare providers are advised to assess patients’ capabilities, beliefs, and values, engage in collaborative decision making, and assist patients in accessing self-management resources. At the organizational level, self-management support is enhanced through staff training, awareness of barriers, and availability of resources.

Following the principles of theory development, the model's dimensions and structural components are presented in a systematic order to provide clarity and understanding. The following steps are followed prior to addressing the final model: (i) explaining the context of the theory; (ii) defining the assumptions and concepts; (iii) explaining the goals; and (iv) describing the organization and relationship between theory components (concepts, statements, and goals).

Structural Components of Holistic Supporting Model for Pain Self-Management

Under the framework of the HSPS, this comprehensive model encompasses various components, including assumptions, the paradigmatic concept, metaparadigmatic concepts, model objectives, and strategies or operational steps, all aimed at guiding pain self-management in cancer patients.

Assumptions

The main presuppositions/assumptions of HSPS model include:

- Enhancing patients’ self-management knowledge and attitudes contributes to the promotion of patient self-management.

- Acknowledging and addressing the religious and spiritual beliefs of cancer patients can facilitate improved self-management.

- Enhancing the knowledge and attitudes of physicians and nurses regarding pain management in cancer patients leads to increased pain self-management in this population.

- Implementation of a holistic supporting model that incorporates enhanced self-management techniques enhances pain self-management among cancer patients.

- Implementation of a holistic supporting model that emphasizes and promotes self-management improves the engagement of cancer patients, physicians, nurses, and the organization as a whole in pain management.

- Implementation of a holistic supporting model that incorporates enhanced self-management practices enhances the organizational structure, providing necessary facilities for pain management and ultimately enhancing client satisfaction with the pain management process.

The HSPS model elucidates the model's main concepts, encompassing both paradigmatic and metaparadigmatic concepts.

Paradigmatic concept of a holistic supporting model for pain self-management

HSPS could have a significant impact on the effectiveness of pain management in cancer patients. The model involves the systematic provision of education and supportive interventions by healthcare staff. This aims to enhance patients’ skills and confidence in managing their health problems. It also focuses on empowering physicians and nurses in pain management for cancer patients. Furthermore, the model emphasizes the improvement of organizational structure to facilitate holistic pain self-management in cancer patients.

Metaparadigmatic concepts of a holistic supporting model for pain self-management

The metaparadigmatic concepts of a holistic supporting model for pain self-management include human, nursing, health and environment.

▪ Human

The central and fundamental concept in nursing is the human being. Nursing theories commonly define a person as someone whose needs are unmet due to illness or who requires assistance in maintaining their health. A human being is a complex entity, encompassing biological, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions. They possess unique needs and exhibit distinct behaviors driven by logical thinking to fulfill those needs. Within the context of this model, the human being serves as the primary focus of nursing care. The experience of cancer pain profoundly impacts their physical, psychological, and social wellbeing, altering their life trajectory. It often leads to mood disorders and disrupts their daily life, necessitating support and education. Despite these challenges, humans demonstrate resilience, creativity, and the ability to utilize internal resources to cope with pain, such as employing inner self-control and liberating themselves from negative thoughts.

▪ Nursing

In the holistic supporting model, the nurse assumes the role of a responsible and accountable caregiver who delivers specialized care and makes informed decisions based on their expertise, utilizing their communication skills and adherence to professional care standards to enhance patients’ pain self-management. Nursing plays a crucial role in assisting patients in the self-management of their pain. Understanding patients’ cultures, beliefs, and individual needs is fundamental to nursing practice. The nurse must be knowledgeable about various pain self-management options to meet the unique needs of each patient. In this model, the nurse assesses clients’ behaviors, requirements, and challenges at each stage of pain self-management, identifies the factors influencing self-management and the barriers to optimal pain management, and then employs strategies to overcome these barriers and promote positive self-management approaches.

▪ Health

In this model, health is defined as a subjective experience characterized by pain relief and patient satisfaction. It encompasses the patient's overall sense of wellbeing, comfort, and relaxation, as well as the reduction of stress and discomfort. The ultimate goal is to promote patient satisfaction with their pain management and overall health outcomes. Healthcare providers recognize that addressing pain in isolation is insufficient and that a comprehensive approach is needed to consider the individual's physical, emotional, social, and spiritual wellbeing. By adopting a holistic perspective, the model emphasizes the importance of tailoring pain management strategies to individual needs, preferences, and goals, promoting a sense of wholeness and improving the patient's quality of life.

▪ Environment

In the holistic supporting model for pain self-management of cancer patients, the environment is viewed as both internal and external. The internal environment refers to an individual's internal beliefs, values, and perceptions, which interact with the external environment. The external environment includes various individuals such as nurses, physicians, other healthcare teams, families, and the organizational facilities. It encompasses everything within or around the client that can influence the phenomenon of pain self-management and can be modified or altered to promote pain relief. The interaction between the internal and external environments plays a crucial role in shaping the pain self-management experience for the patient.

Model objectives

The objectives of a model or theory are the desired outcomes that the theorist aims to achieve. In the holistic supporting model for pain self-management of cancer patients, the following objectives are identified:

Enhancing pain self-management skills in cancer patients and their family: The model aims to improve patients and family ability to effectively manage their pain through education, support, and the development of self-management strategies.

Empowering physicians and nurses in pain management of cancer patients: The model emphasizes the importance of enhancing the knowledge, attitudes, and skills of healthcare professionals in pain management to ensure comprehensive and effective care for cancer patients.

Enhancing the organizational structure in pain management of cancer patients: The model recognizes the significance of organizational support and infrastructure in facilitating pain management for cancer patients. It seeks to enhance the organizational structure and processes to ensure optimal pain management outcomes and patient satisfaction.

Strategies or Operational Steps of a Holistic Supporting Model for Pain Self-Management in Cancer Patients

Operational Steps to Empowering Cancer Patients and Their Family in Pain Self-Management

Patient-related barriers, such as negative attitudes toward analgesics and opioids, as well as a lack of information about pain management options, hinder cancer patients’ ability to self-manage their pain. Cancer pain exerted substantial psychological effects, encompassing mood disorders (e.g., irritability, frustration, crying, nostalgia, boredom, self-blame, decreased life satisfaction, and suicidal thoughts) and a sense of worthlessness (e.g., diminished self-esteem, grief due to the loss of one’s former self, limited autonomy, and role constraints). Participants’ narratives revealed that living with cancer pain caused family turmoil, with family members frequently experiencing anxiety and stress. Financial challenges emerged as patients became unable to work, impacting the wellbeing of their families. Furthermore, participants expressed concerns regarding their children's lives and future, observing a diminished interest in marriage and a preoccupation with the illness of their family members, which diverted attention away from educational pursuits.

To effectively address the barriers outlined above and facilitate optimal pain self-management, it is recommended to implement the following strategies:

- Assess patients’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding cancer pain and its self-management.

- Conduct a comprehensive review of patients’ educational needs related to various pain management strategies.

- Engage in discussions with patients to highlight the significance, benefits, and limitations of adopting nonpharmacological pain management strategies.

- Develop informative materials such as visually appealing and appropriate information sheets, videos, audiotapes, and booklets on pain management.

- Provide education on the origins and nature of cancer pain, pharmacological and nonpharmacological management options, drug side effects and safety, as well as common misconceptions about opioid usage (e.g., addiction and tolerance).

- Conduct educational sessions to teach patients how to utilize numerical self-rating scales to quantify pain severity, emphasize the importance of reporting and monitoring pain, and adhere to medication schedules.

- Integrate patient and family education into person-centered communication, enhancing patients’ feeling of control and self-efficacy.

- Creating a supportive environment without burdening the patient enhances the effectiveness of received support. Raising family members’ awareness of this can encourage their efforts in alleviating the patient’s burden.

- Assist patients in effectively communicating with healthcare providers and coordinating care among different providers based on their personal needs.

- Reassure patients that the majority of pain can be controlled, if not entirely eliminated, through appropriate pain management strategies.

- Integrate patients with significant individuals in patient care and provide them with spiritual support. Also, offer counseling sessions to cancer patients to enhance their mood.

- Offer supportive interventions to address the needs of family members and caregivers of cancer patients.

- Provide adequate support and resources to help family members and caregivers manage their competing roles effectively.

- Develop strategies to minimize the stress and burden associated with caregiving responsibilities.

Practical Strategies for Empowering Physicians and Nurses in Pain Management of Cancer Patients

To ensure healthcare providers are equipped to effectively manage cancer pain, both physicians and nurses should be empowered with the necessary knowledge and skills. The following strategies can be implemented:

- Incorporate comprehensive education on cancer pain management and palliative care into nursing and medical curriculums through various instructional methods such as instructional lectures, rotations, and interdisciplinary rounds. This initiative aims to enhance medical students’ knowledge and attitudes toward pain management.

- Promote healthcare providers’ awareness of the influence of patients’ cultural and spiritual values and beliefs on their pain self-management.

- Screen for and measure pain of patients using reliable pain assessment tools such as the numeric rating scale and visual analog scale.

- Ensure timely pain reassessment and incorporate effective pain management practices into routine clinical practice.

- Stay updated with current guidelines for cancer pain management, such as those provided by the WHO, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, and American Pain Association.

- Conduct multidimensional evaluations, considering physical, functional, psychosocial, and spiritual aspects, to develop individualized treatment plans that also account for social, economic, and cultural considerations.

- Establish regular follow-up programs for cancer pain management to ensure continuous pain assessment and appropriate interventions.

Practical Strategies to Enhance the Organizational Structure to Facilitate Holistic Support for Cancer Patients’ Pain Self-Management

To address organizational barriers and promote holistic pain management in cancer patients, the following strategies can be implemented:

- Elevate pain management as a major and high-priority issue within healthcare organizations.

- Establish policies, philosophies, and rules that emphasize the importance of effective pain management.

- Include pain management as a criterion in hospital accreditation processes.

- Form a dedicated pain management team consisting of a nurse, physician, anesthesiologist, and pharmacologist, with a nurse serving as the team leader.

- Establish certification for nurses in pain treatment using objective assessments and performance checklists.

- Improve interdisciplinary pain management services by collaborating with palliative care physicians and enhancing the referral system.

- Support opioid availability and integrate palliative care services for cancer pain management.

Discussion

The HSPS model is a supportive framework aimed at facilitating comprehensive support for pain self-management in cancer patients. By effectively managing pain, the model aims to enhance patients’ feelings of satisfaction and reduce their stress levels. It is grounded in evidence-based research, incorporating findings from grounded theory and other relevant studies.

This study revealed that cancer pain encompasses physical, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions that necessitate comprehensive management. The HSPS model adopts a holistic approach that considers all facets of pain. Novy's biopsychosocial model extensively addresses various aspects of cancer pain throughout the disease progression (Novy & Aigner, 2014). According to Baydoun's theory of symptom self-care management in cancer and Otis-Green's psychosocial and spiritual model for cancer pain management, cancer-related symptoms encompass physiological, psychological, and situational elements, reflecting their complex nature (Baydoun et al., 2018; Otis-Green et al., 2002). Consequently, employing a holistic approach to pain management in cancer proves advantageous.

This model investigated the unique responsibilities of patients, healthcare providers, and the healthcare system in promoting pain self-management among cancer patients. Patients encounter various barriers throughout the pain management journey. They necessitate support due to several patient-related barriers, such as accepting and enduring pain, negative attitudes toward opioids and pain management, and lack of knowledge regarding pain self-management strategies, which hinder effective pain management. Damush’s study revealed that pain self-management training enhanced patients’ self-management behaviors and self-efficacy in controlling symptoms among primary care patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain and depression (Damush et al., 2016). Various components of self-management support were identified as crucial, encompassing the provision of information, utilization of psychological strategies, offering condition-specific practical support, and fostering social support (Taylor et al., 2015). Jahn's model identifies three key factors that impact pain-related health behavior. These factors consist of predisposing variables, encompassing beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions; enabling factors, including knowledge and abilities; and reinforcing factors, such as feedback from family or healthcare professional (Jahn et al., 2014). Overcoming patient barriers is crucial for enhancing and maintaining effective pain management. Patient education plays a vital role in enabling patients to actively engage in their pain treatment and develop self-management skills. The benefits of successful pain management in cancer patients extend beyond mere improvement, satisfaction, and stress reduction. According to Baydoun et al., effective pain management also leads to improved functional and cognitive performance, enhanced psychological and spiritual wellbeing, and overall better quality of life (Baydoun et al., 2018).

Considering the existing knowledge gaps and negative attitudes among some healthcare professionals, one of the primary objectives of the HSPS model was to empower physicians and nurses in the management of cancer pain. Davies emphasized that a lack of training among health professionals posed a barrier to the provision of self-management support. He further emphasized the need for clinicians to receive education and skill development in the field of self-management support (Davies, 2019). Jahn indicated that SCION-PAIN (Self Care Improvement through Oncology Nursing) interventions effectively enhanced cancer patients’ pain self-management by optimizing both pharmacological and nonpharmacological pain treatment approaches. These interventions encompassed pain-related discharge management, counseling, and efforts to reduce barriers experienced by patients. As a result, cancer patients experienced improved pain management outcomes (Jahn et al., 2014). Hence, it is worth acknowledging that physicians and, notably, nurses hold vital roles as integral members of the supportive or palliative care team.

The findings of this study highlight the significance of the healthcare system in ensuring proper pain management for cancer patients. Prioritizing pain care, improving the referral system, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, and ensuring adequate access to opioids are among the key challenges that health systems and policymakers need to address. Recognizing the importance of organizational support, healthcare practitioners should be empowered to integrate self-management support into their routine clinical practices (Taylor et al., 2015). At the policy level, self-management has been recognized as a potential solution to alleviate the strain faced by the under-resourced healthcare system (Kendall et al., 2011). Otis-Green emphasizes the significance of ongoing interdisciplinary collaboration in delivering excellent cancer pain management (Otis-Green et al., 2002). Similarly, Ventura suggests that complex, multimodal, and interdisciplinary approaches have led to more contextually tailored treatments, resulting in improved outcomes and sustainability (Ventura et al., 2018). In essence, engaging with a multidisciplinary team may contribute to enhanced patient outcomes and wellbeing.

Finally, it is important to recognize that effective pain management in cancer patients is a multidimensional concept that necessitates a holistic and comprehensive approach. Therefore, interventions to promote pain self-management in cancer patients should be implemented across various levels, including the patient, healthcare provider, and system. According to Kennedy, a whole-systems approach that focuses on enhancing information, resource accessibility, and professional response can enhance self-management skills (Kennedy et al., 2010). Thus, it can be concluded that multidimensional interventions are more effective than single-dimensional interventions, and a multilevel approach is necessary to achieve sustainable change as these interventions must work in synergy across multiple levels to optimize their effectiveness.

Strengths and Limitations

This study represents a pioneering effort in presenting a comprehensive holistic model for enhancing cancer pain self-management. The proposed model offers a framework that addresses the factors supporting patients, nurses, and healthcare systems in promoting pain self-management. The findings of this study have significant implications for clinical practice and education, serving as a foundation for hypothesis testing and informing theoretical frameworks. Furthermore, given the vital role of family members in the pain management of cancer patients, it is recommended to conduct a separate study that delves deeper into their experiences in the context of pain management. Such an exploration would provide valuable insights and further enhance our understanding of the dynamics surrounding pain management within the familial context. It is important to note that this study was conducted during the challenging period of the COVID-19 pandemic. The researcher encountered difficulties in accessing oncology wards, recruiting diverse participants, and allocating sufficient interview time due to heightened precautions and restrictions. These limitations should be acknowledged, as they may have influenced certain aspects of the study's results and interpretations.

Implications for Practice

Due to the significant amount of time nurses spend with patients compared to other healthcare providers, they are well-positioned to play a crucial role in improving cancer pain management across all levels, including the patient, healthcare provider, and system. At the patient level, it is important to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of cancer patients regarding pain. Their educational needs should be identified, and comprehensive training should be provided to empower them with various pharmacological and nonpharmacological pain management strategies. To enhance the knowledge and attitudes of physicians and nurses, pain management training programs should be implemented at the healthcare provider level, both during their education at universities and through in-service training. At the system level, efforts should be made to strengthen the referral system and ensure broader access to medications. Health policymakers should prioritize the significance of pain management and palliative care, allocating adequate attention and resources to these areas.

Conclusions

As the life expectancy of cancer patients continues to increase, it becomes crucial to develop middle-range theories that guide self-management in this population. This paper outlines the process employed to construct the Theory of Holistic Supporting Model from Cancer Pain Self-Management. Given the prevalence of persistent pain among cancer patients, it is imperative to prioritize effective pain management in this population. Recognizing the multifaceted nature of cancer pain, this model advocates for a comprehensive approach that attends to all dimensions of pain, including physical, functional, psychosocial, cultural, and spiritual aspects. By encompassing all levels of the patient, healthcare provider, and health system, this model aims to enhance pain self-management and provide comprehensive support.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients for kindly accepting to take part in this research.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: SO and HH designed and conducted the study and prepared the manuscript. SO, HH, AR, AD, and AA performed data analysis. ZS helped to select the study participants. Versions of the manuscripts were shared, revised, and written by all authors. All authors have read and approved the submitted manuscript.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Consideration: The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (ethical code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.147).

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: There was funding for this study with grant ID IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.147.

ORCID iD: Samira Orujlu https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8082-1698

References

- Baker T. A., O’Connor M. L., Krok J. L. (2014). Experience and knowledge of pain management in patients receiving outpatient cancer treatment: What do older adults really know about their cancer pain? Pain Medicine, 15(1), 52–60. 10.1111/pme.12244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baydoun M., Barton D. L., Arslanian-Engoren C. (2018). A cancer specific middle-range theory of symptom self-care management: A theory synthesis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74(12), 2935–2946. 10.1111/jan.13829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J., Strauss A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Damush T., Kroenke K., Bair M., Wu J., Tu W., Krebs E., Poleshuck E. (2016). Pain self-management training increases self-efficacy, self-management behaviours and pain and depression outcomes. European Journal of Pain, 20(7), 1070–1078. 10.1002/ejp.830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies F. (2019). Training health professionals to support people with progressive neurological conditions to self-manage: A realist inquiry. Cardiff University. [Google Scholar]

- ElMokhallalati Y., Mulvey M. R., Bennett M. I. (2018). Interventions to support self-management in cancer pain. Pain Reports, 3(6), e690. 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay J., Colombet M., Soerjomataram I., Parkin D. M., Piñeros M., Znaor A., Bray F. (2021). Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. International Journal of Cancer, 149(4), 778–789. 10.1002/ijc.33588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow W. E., Whitlock E. (2002). A’s behavior change model adapted for self-management support improvement. Change. [Google Scholar]

- Greco M. T., Roberto A., Corli O., Deandrea S., Bandieri E., Cavuto S., Apoloneia G. (2014). Quality of cancer pain management: An update of a systematic review of undertreatment of patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32(36), 4149–4154. 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.0383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn P., Kuss O., Schmidt H., Bauer A., Kitzmantel M., Jordan K., Krasemann S., Landenberger M. (2014). Improvement of pain-related self-management for cancer patients through a modular transitional nursing intervention: A cluster-randomized multicenter trial. PAIN®, 155(4), 746–754. 10.1016/j.pain.2014.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall E., Ehrlich C., Sunderland N., Muenchberger H., Rushton C. (2011). Self-managing versus self-management: Reinvigorating the socio-political dimensions of self-management. Chronic Illness, 7(1), 87–98. 10.1177/1742395310380281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy A., Chew-Graham C., Blakeman T., Bowen A., Gardner C., Protheroe J., Rogers A., Gask L. (2010). Delivering the WISE (Whole Systems Informing Self-Management Engagement) training package in primary care: Learning from formative evaluation. Implementation Science, 5(7), 1–15. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy A., Rogers A., Bower P. (2007). Support for self care for patients with chronic disease. BMJ, 335(7627), 968–970. 10.1136/bmj.39372.540903.94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y. S., Guba E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lou F., Shang S. (2017). Attitudes towards pain management in hospitalized cancer patients and their influencing factors. Chinese Journal of Cancer Research, 29(1), 75. 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2017.01.09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckett T., Davidson P. M., Green A., Marie N., Birch M.-R., Stubbs J., Phillips J., Agar M., Boyle F., Lovell M. (2019). Development of a cancer pain self-management resource to address patient, provider, and health system barriers to care. Palliative & Supportive Care, 17(4), 472–478. 10.1017/S1478951518000792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertilus D. S. D., Lengacher C. A., Rodriguez C. S. (2021). A review and conceptual analysis of cancer pain self-management. Pain Management Nursing, 23(2), 168–173. 10.1016/j.pmn.2021.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novy D. M., Aigner C. J. (2014). The biopsychosocial model in cancer pain. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care, 8(2), 117–123. 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orujlu S., Hassankhani H., Rahmani A., Sanaat Z., Dadashzadeh A., Allahbakhshian A. (2021). The process of pain management by cancer patients: a grounded theory study and model presentation, PhD thesis, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

- Orujlu S., Hassankhani H., Rahmani A., Sanaat Z., Dadashzadeh A., Allahbakhshian A. (2022). Barriers to cancer pain management from the perspective of patients: A qualitative study. Nursing Open, 9(1), 541–549. 10.1002/nop2.1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otis-Green S., Sherman R., Perez M., Baird R. P. (2002). An integrated psychosocial-spiritual model for cancer pain management. Cancer Practice, 10(S1), s58–s65. 10.1046/j.1523-5394.10.s.1.13.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. J., Pinnock H., Epiphaniou E., Pearce G., Parke H. L., Schwappach A., Purushotham N., Jacob S., Griffiths C. J., Greenhalgh T. (2015). A rapid synthesis of the evidence on interventions supporting self-management for people with long-term conditions: PRISMS–Practical systematic Review of Self-Management Support for long-term conditions. Southampton: NIHR Journals Library; (Health Services and Delivery Research, No. 2.53.). 10.3310/hsdr02530 [DOI] [PubMed]

- van Dongen S. I., De Nooijer K., Cramm J. M., Francke A. L., Oldenmenger W. H., Korfage I. J., Witkamp F. E., Stoevelaar R., van der Heide A., Rietjens J. A. (2020). Self-management of patients with advanced cancer: A systematic review of experiences and attitudes. Palliative Medicine, 34(2), 160–178. 10.1177/0269216319883976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura J., Sobczak J., Chung J. (2018). The chronic knee pain program: A self-management model. International Journal of Orthopaedic and Trauma Nursing, 29, 10–15. 10.1016/j.ijotn.2018.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker L. O., Avant K. C. (2011). Strategies for theory construction in nursing (Vol. 4). Pearson/Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2020). World Health Organization (WHO), Global Health Estimates 2020: Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000–2019. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death

- Yamanaka M. (2018). A concept analysis of self-management of cancer pain. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 5(3), 254–261. 10.4103/apjon.apjon_17_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]