Resumo

Fundamento

Sabe-se que em torno de 30% dos pacientes apresentam valores de pressão arterial (PA) mais elevados quando examinados no consultório do que em suas residências. No mundo, admite-se que apenas 35% dos hipertensos já tratados tenham alcançado meta pressórica.

Objetivo

Fornecer dados epidemiológicos sobre o controle da PA nos consultórios, em uma amostra de cardiologistas brasileiros, avaliado pela medida de consultório e monitorização residencial da pressão arterial (MRPA).

Métodos

Análise transversal. Observou-se pacientes com diagnóstico de hipertensão arterial, em tratamento anti-hipertensivo, podendo ou não estar com a PA controlada. A PA foi verificada no consultório por profissional médico, e no domicílio através da MRPA. A associação entre variáveis categóricas se deu por meio do teste do qui-quadrado (p < 0,05).

Resultados

Foram incluídos 2.540 pacientes, com idade média 59,7 ± 15,2 anos. A maioria dos pacientes eram mulheres (62%; n = 1.575). O estudo mostrou uma prevalência de 15% (n = 382) de hipertensão do avental branco não controlada, e 10% (n = 253) de hipertensão mascarada não controlada. A taxa de controle da PA no consultório foi 56,3%, e no domicílio, de 61%; 46,4% dos pacientes tiveram PA controlada no consultório e fora dele. Observou-se maior controle no sexo feminino e na faixa etária 49-61 anos. Observando o controle domiciliar com o novo ponto de corte das Diretrizes Brasileiras de Hipertensão Arterial de 2020, a taxa de controle foi de 42,4%.

Conclusão

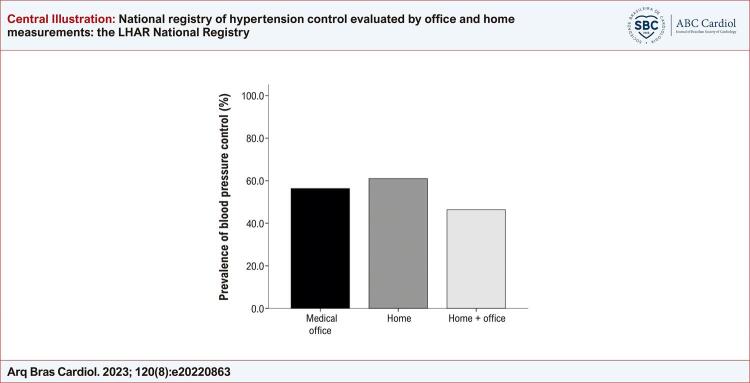

O controle pressórico nos consultórios em uma amostra de cardiologistas brasileiros foi de 56,3%; 61% quando a PA foi obtida no domicílio, e 46,4% quando o controle foi observado tanto no consultório como no domicílio.

Keywords: Hipertensão, Pressão Arterial, Monitorização Residencial da Pressão Arterial, Controle Pressórico

Introdução

A hipertensão arterial (HA) é uma condição crônica definida por valores persistentemente elevados de pressão arterial (PA) que, se não devidamente controlados, gera repercussões sistêmicas causadas por lesões estruturais e/ou funcionais a órgãos-alvo. A HA é o principal fator de risco modificável para os eventos cardiovasculares e cerebrovasculares. É considerada um importante problema de saúde pública por apresentar prevalência alta e crescente, baixos índices de controle e morbidade/mortalidade elevadas.1 - 4 A frequência autorreferida de diagnóstico médico de HA na população adulta das capitais brasileiras e Distrito Federal é de 25,2%, sendo maior entre mulheres (26,2%) do que entre homens (24,1%). Em ambos os sexos, essa frequência aumentou com a idade e diminuiu com o nível de escolaridade.5

A mensuração da PA é, naturalmente, imprescindível para o diagnóstico. No entanto, apesar de ser um procedimento simples, podem ocorrer erros durante sua medição, sejam relacionados ao aparelho, à técnica, à influência do ambiente, ao próprio paciente ou, ainda, ao observador.6 , 7 O diagnóstico de HA é dado, segundo os novos critérios da diretriz americana, quando o indivíduo apresenta valor de PA sistólica (PAS) ≥ 130 mmHg e/ou PA diastólica (PAD) ≥ 80 mmHg, tanto em medida no consultório quanto domiciliar e ambulatorial.8 A última Diretriz Brasileira, a Europeia de 2018, como também a Diretriz da Sociedade Internacional de HA 2020, mantêm os critérios anteriores, considerando como hipertenso o indivíduo que apresenta PAS ≥ 140 e/ou PAD ≥ 90 mmHg para medidas em consultório. A Diretriz Europeia e Brasileira trás, no entanto, mudanças nas recomendações sobre quando se considerar o início do tratamento medicamentoso de acordo com o risco cardiovascular.1 , 9 , 10 , 11

Sabe-se que porcentagem significativa – em torno de 30% – dos pacientes apresenta valores de PA mais elevados quando examinados no ambiente de consultório do que em suas residências.12 - 14 A hipertensão do avental branco (HAB) ocorre quando há elevação pressórica persistente no ambiente assistencial e valor normal fora dele, levando à superestimação dos níveis de PA do paciente e consequente erro no diagnóstico da HA. O oposto da HAB ocorre quando o paciente apresenta níveis pressóricos dentro dos limites de normalidade em medida realizada no consultório, porém PA elevada fora dele, o que caracteriza a hipertensão mascarada (HM). Para que seja possível diferenciar a HAB da hipertensão sustentada ou, ainda, para que se identifique a presença da HM, é necessário que se faça a medição da PA do paciente fora do ambiente médico. Os métodos atualmente utilizados são a monitorização ambulatorial da pressão arterial (MAPA) e a monitorização residencial da pressão arterial (MRPA).13 - 17

A MRPA é o registro da PA realizado durante a vigília pelo paciente ou outra pessoa treinada, através de aparelho automático, por vários dias, fora do ambiente de consultório, com número de medidas e horários previamente determinados. A MRPA demonstrou ser o método diagnóstico da HA que melhor atua na eliminação dos efeitos anteriormente citados,18 com as vantagens adicionais de apresentar boa reprodutibilidade, boa capacidade prognóstica, avaliação do efeito do tratamento em diferentes períodos do dia, custo relativamente baixo e boa aceitação pelo paciente. Uma revisão sistemática concluiu que tanto a baixa sensibilidade da medida de consultório para detectar o controle ótimo da PA quanto a associação da MRPA com mortalidade cardiovascular apoiam o uso rotineiro desta última na prática clínica.19 Estudos demonstraram que a utilização da MRPA no seguimento do paciente hipertenso está associada à melhor adesão ao tratamento medicamentoso, com consequente melhora no controle da PA e redução nos desfechos cardiovasculares quando comparada com a PA medida no consultório.7 , 20

No mundo, admite-se que menos de 15% da população total de hipertensos tenham alcançado a meta pressórica recomendada, e essa taxa é de apenas 35% entre os hipertensos já tratados.1 O fato ganha magnitude quando levamos em consideração que as metas pressóricas recomendadas pelas diretrizes mais recentes1 , 2 , 8 - 11 tornaram-se mais baixas, o que tende a aumentar o percentual de indivíduos hipertensos não controlados e, por consequência, o risco associado de morbidade e mortalidade de doenças cardiovasculares. O primeiro registro brasileiro de hipertensão,21 usando um ponto de corte mais baixo para controle da PA (< 130 × 80 mmHg), encontrou 24,3% da população geral controlados no início da observação, e 24,7% em 1 ano.

Assim, este estudo tem como objetivo fornecer dados epidemiológicos sobre o controle da HA nos consultórios em uma amostra de cardiologistas brasileiros, avaliado pela medida de consultório e residencial (MRPA).

Métodos

Trata-se de uma análise transversal, realizada em 231 centros particulares de atenção especializada em cardiologia, localizados em 23 estados brasileiros e mais o Distrito Federal, englobando todas as cinco regiões do Brasil, entre junho e dezembro de 2019. A amostra foi obtida por conveniência e constituída por pacientes com diagnóstico médico de HA, atendidos ambulatorialmente, com idade ≥ 18 anos, em tratamento anti-hipertensivo, podendo ou não estar com a PA controlada. Solicitou-se aos médicos investigadores que convidassem para participar da pesquisa sempre o segundo paciente do dia, para evitar um viés de seleção.

Preliminarmente, os participantes foram informados sobre os objetivos e procedimentos da pesquisa e, a seguir, convidados a participar voluntariamente do estudo. Procedeu-se a coleta de dados após a assinatura no Termo de Consentimento Livre e Esclarecido. O referido estudo foi aprovado pelo Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa Humana do Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Goiás com o CAEE: 08208619.8.0000.5078.

Foram coletados dados demográficos, clínicos e antropométricos. As variáveis data de nascimento, idade, sexo e uso ou não de medicação anti-hipertensiva foram coletadas através de questionário durante o atendimento. O peso e altura foram obtidos usando balanças antropométricas devidamente calibradas e validadas, e o índice de massa corpórea (IMC) de adultos classificado segundo a Organização Mundial da Saúde.22

A medida da PA de consultório foi realizada por profissional médico, segundo as recomendações das VII Diretrizes Brasileiras de Hipertensão Arterial (VII DBHA),1 utilizando-se manguito apropriado em conformidade com as dimensões do braço do indivíduo. Não participaram do estudo pacientes com arritmia e circunferência do braço > 42 cm e < 22 cm, devido às limitações do medidor de PA.

A MRPA foi obtida segundo as orientações da IV Diretriz de Monitorização Residencial da Pressão Arterial e da Diretriz Europeia de Hipertensão Arterial.7 , 9 Dessa forma, foram adquiridas duas medidas no primeiro dia, ainda no ambiente do ambulatório (essas medidas não foram utilizadas para análise da média residencial), e medidas domiciliares de 4 dias consecutivos, com três medidas pela manhã e três medidas no horário noturno, totalizando 24 medidas. Os pacientes foram instruídos a realizar as medidas conforme protocolo e anotar num diário de PA para aumentar a adesão à metologia da MRPA. As medidas, também, foram registradas e armazenadas na memória do equipamento e posteriormente inseridas na plataforma TeleMRPA®, uma ferramenta de laudo a distância por telemedicina. Tanto a medida da PA de consultório como a MRPA foram obtidas através do equipamento eletrônico HEM 7320 (Omron Healthcare Co. Ltd., Kyoto Japan).

Considerou-se HA não controlada, com base na medida do consultório, daqueles participantes que tinham PAS ≥ 140 mmHg e/ou PAD ≥ 90 mmHg, e com base na MRPA ≥ 135 mmHg para PAS e/ou ≥ 85 mmHg para PAD. Adicionalmente, analisamos a taxa de controle domiciliar com base nos novos valores de corte para MRPA, recomendados pela DBHA 202011 . Utilizou-se os termos HM não controlada (HMNC) para aqueles participantes da pesquisa que tiveram PA controlada no consultório, mas PA domiciliar ou ambulatorial elevada; HAB não controlada (HABN) para aqueles que tiveram a PA elevada no consultório, mas PA controlada residencial ou ambulatorial, e hipertensão sustentada (HS) para aqueles que tiveram a PA não controlada no consultório e ambulatorial. Embora os termos HAB e HM fossem, originalmente, definidos para pessoas que não estavam sendo tratadas para HA, nos últimos tempos, também, são usadas para descrever discrepâncias entre a PA no consultório e fora do consultório em pacientes tratados para HA.9 , 23

O banco de dados foi estruturado em Excel® (Microsoft) com os dados da MRPA importados da plataforma de registro, assim como os demais dados coletados pelos investigadores. As variáveis contínuas estão apresentadas como média e desvio padrão, enquanto as categóricas como frequências relativas e absolutas. A associação entre variáveis categóricas se deu por meio do teste do qui-quadrado. Adotou-se um valor de significância de p < 0,05. Foi utilizado o programa estatístico SPSS v. 21.0 (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL, EUA).

Resultados

A amostra estudada foi de 2.540 pacientes, sendo 1,9% (n = 49) dos participantes da pesquisa da região Norte, 18% (n = 458) da região Nordeste, 58,2% (n = 1479) da região Sudeste, 13,5% (n = 342) da região Sul, e 8,3% (n = 211) da região Centro-Oeste. Desses, 1.575 (62%) eram do sexo feminino, e 965 (38%), do sexo masculino. A idade média foi de 59,7 ± 15,2 anos, e o IMC médio, de 28,6 ± 5,1 kg/m2 ( Tabela 1 ).

Tabela 1. – Características descritivas da amostra (n = 2.540).

| Variável | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| IMC | ||

| Desnutrição | 23 | 0,9 |

| Eutrofia | 590 | 23,2 |

| Sobrepeso | 1.070 | 42,1 |

| Obesidade | 857 | 33,7 |

| Sexo | ||

| Feminino | 1.575 | 62,0 |

| Masculino | 965 | 38,0 |

| Média | DP | |

| Idade (anos) | 59,7 | 15,2 |

| IMC (kg/m2) | 28,6 | 5,1 |

Fonte: dados da pesquisa. IMC: índice de massa corpórea; DP: desvio-padrão.

Os valores médios da PA de consultório foram de 133,3 ± 20,4 mmHg e 82,3 ± 13,2 mmHg, e pela MRPA as médias foram de 125,9 ± 16,1 mmHg, e 78,6 ± 9,3 mmHg para PAS e PAD, respectivamente. Os participantes da pesquisa tiveram 14 ou mais medidas válidas na MRPA, tendo a maioria (94%) dos participantes um total de 24 medidas válidas. O estudo mostrou uma prevalência de 15% (n = 382) de HABNC e 10% (n = 253) de HMNC ( Tabela 2 ).

Tabela 2. – Prevalência dos diferentes fenótipos de hipertensão (n = 2.540).

| Fenótipos | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| HABNC | 382 | 15 |

| HC | 1.168 | 46 |

| HMNC | 253 | 10 |

| HS | 737 | 29 |

Fonte: dados da pesquisa. HABNC: hipertenso do avental branco não controlado; HC: hipertenso controlado; HMNC: hipertenso mascarado não controlado; HS: hipertenso sustentado.

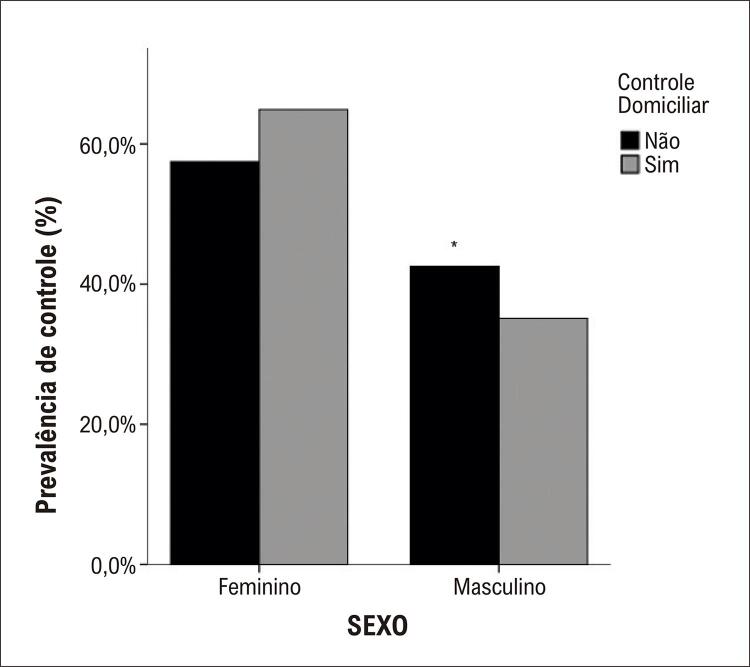

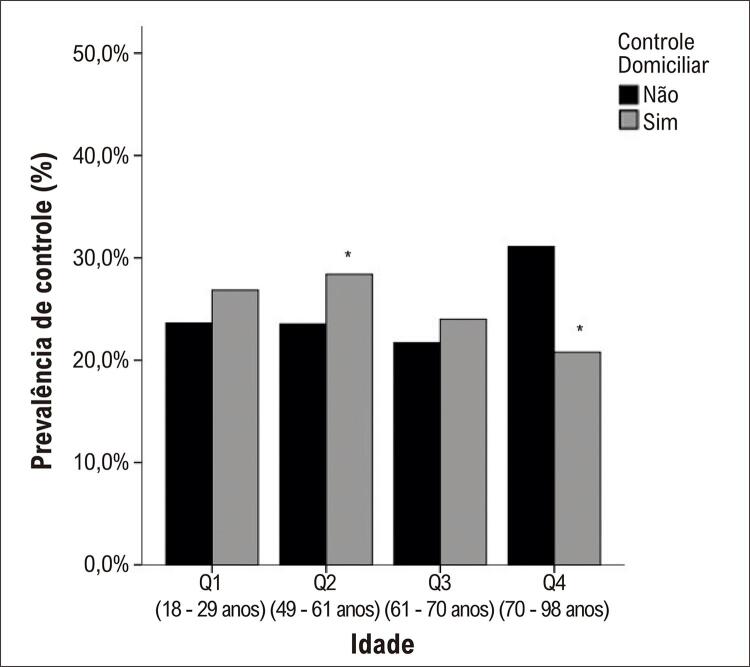

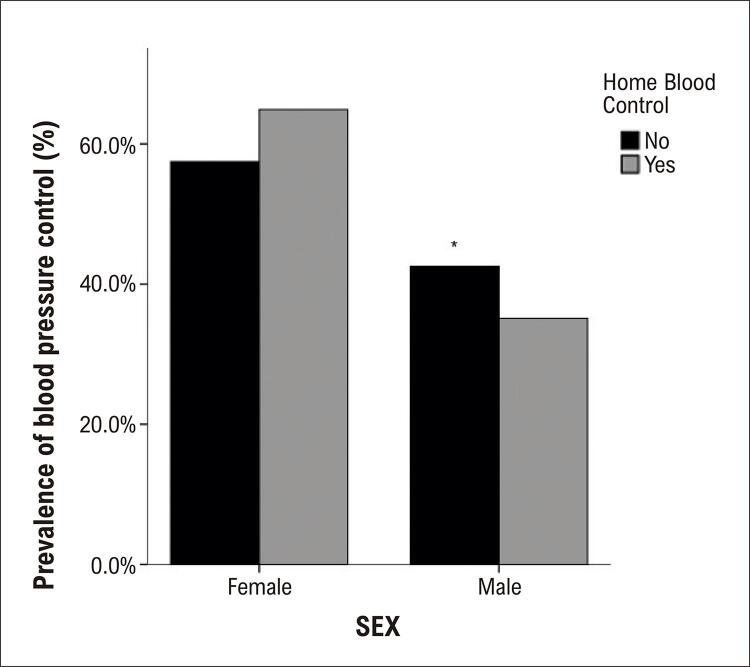

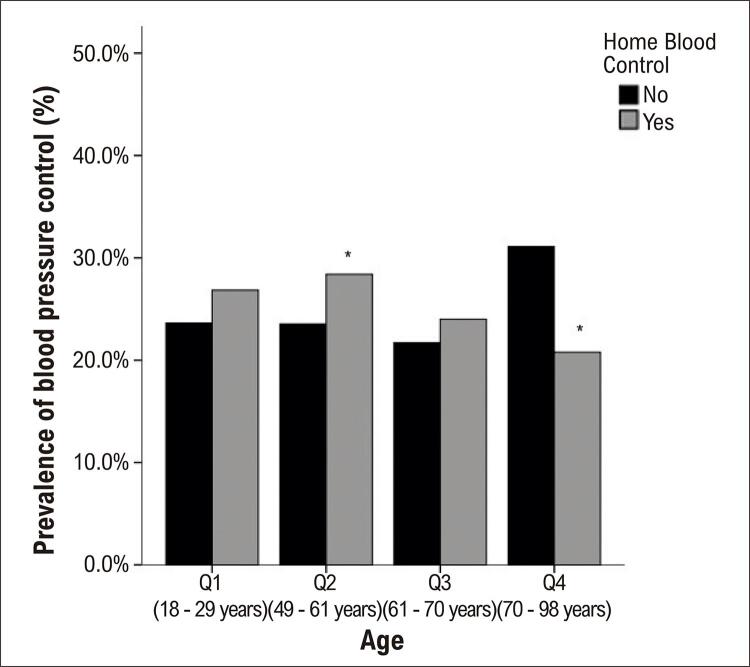

A prevalência de HABNC no sexo feminino foi de 16% (n = 252) e HMNC de 8,4% (n = 132), enquanto no sexo masculino essa prevalência foi de 13,5% (n = 130) para HABNC e 12,5% (n = 121) para HMNC. A prevalência de HMNC no sexo masculino foi significativamente maior que no sexo feminino, enquanto o sexo feminino apresentou o maior número de pacientes controlados. Em relação ao IMC não houve diferença estatística entre os fenótipos de hipertensão, e em relação à faixa etária, os mais idosos (quartil 4 = 70-98 anos) apresentaram a maior prevalência de HMNC e o menor controle pressórico ( Tabela 3 ).

Tabela 3. – Fenótipos versus variáveis.

| Fenótipo | Sexo | p-valor* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Feminino (n = 1.575) | Masculino (n = 965) | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | ||||||

| Fenótipo | < 0,01 | ||||||||

| HABNC | 252 | 16,0 | 130 | 13,5 | |||||

| HC | 754 | 47,9 | 414 | 42,9† | |||||

| HMNC | 132 | 8,4 | 121 | 12,5† | |||||

| HS | 437 | 27,7 | 300 | 31,1 | |||||

| Fenótipo | Índice de massa corpórea | p-valor | |||||||

| Desnutrição (n 23) | Eutrofia (n 590) | Sobrepeso (n 1.070) | Obesidade (n 857) | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Fenótipo | 0,24 | ||||||||

| HABNC | 7 | 30,4 | 84 | 14,2 | 168 | 15,7 | 123 | 14,4 | |

| HC | 8 | 34,8 | 269 | 45,6 | 511 | 47,8 | 380 | 44,3 | |

| HMNC | 1 | 4,3 | 56 | 9,5 | 108 | 10,1 | 88 | 10,3 | |

| HS | 7 | 30,4 | 181 | 30,7 | 283 | 26,4 | 266 | 31,0 | |

| Fenótipo | Idade | p-valor | |||||||

| Q1 (n 650) (18-49 anos) | Q2 (n 673) (49-61 anos) | Q3 (n 587) (61-70 anos) | Q4 (n 630) (70-98 anos) | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Fenótipo | < 0,01 | ||||||||

| HABNC | 97 | 14,9 | 115 | 17,1 | 88 | 15,0 | 82 | 13,0 | |

| HC | 319 | 49,1 | 325 | 48,3 | 284 | 48,4 | 240 | 38,1‡ | |

| HMNC | 62 | 9,5 | 59 | 8,8 | 46 | 7,8 | 86 | 13,7‡ | |

| HS | 172 | 26,5 | 174 | 25,9 | 169 | 28,8 | 222 | 35,2‡ | |

*p-valor para o teste do qui-quadrado. †Essa prevalência difere significativamente da prevalência dos indivíduos do sexo feminino. ‡Essa prevalência difere significativamente da prevalência das demais colunas. HABNC: hipertenso do avental branco não controlado; HC: hipertenso controlado; HMNC: hipertenso mascarado não controlado; HS: hipertenso sustentado.

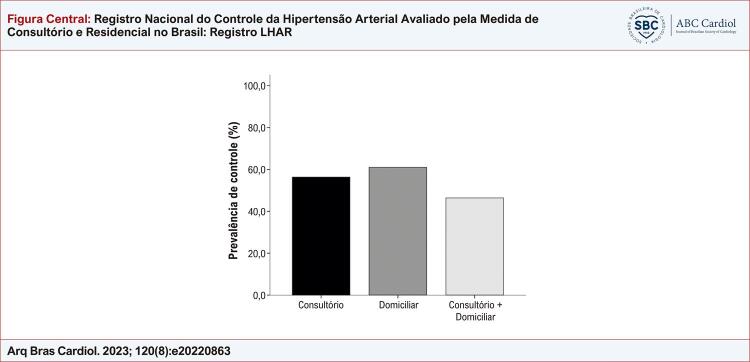

A taxa de controle da PA dos participantes da pesquisa no consultório foi 56,3% (n = 1.431). Já no domicílio, observamos um controle de 61% (n = 1.550), enquanto 46,4% (n = 1.178) dos participantes da pesquisa tiveram PA controlada no consultório e fora dele ( Figura central ).

Figura Central. : Registro Nacional do Controle da Hipertensão Arterial Avaliado pela Medida de Consultório e Residencial no Brasil: Registro LHAR.

Prevalência de controle geral.

Observando o controle domiciliar estratificado pelo sexo ( Figura 1 ) e idade ( Figura 2 ), encontrou-se maior controle no sexo feminino e no quartil 2 (faixa etária 49-61 anos), respectivamente.

Figura 1. – Prevalência de controle pressórico no domicílio estratificado por sexo (p < 0,05).

Figura 2. – Prevalência de controle pressórico no domicílio estratificado por idade (p < 0,05).*.

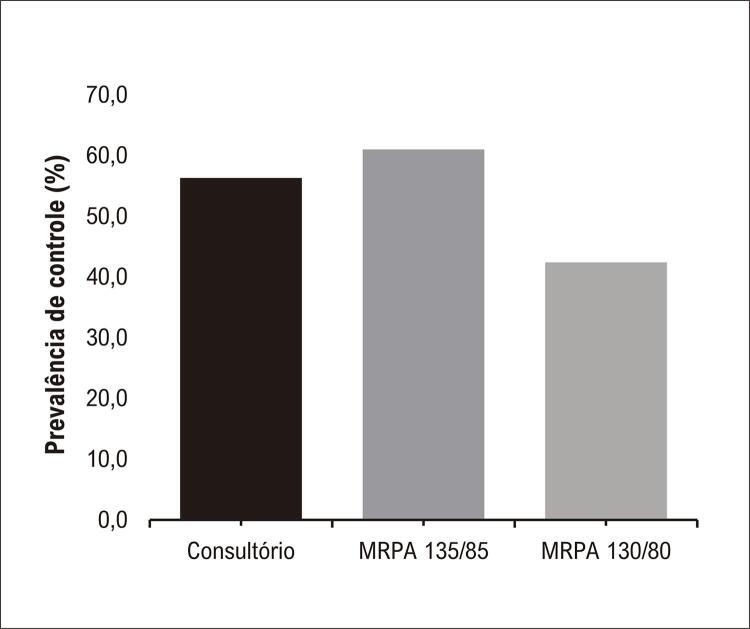

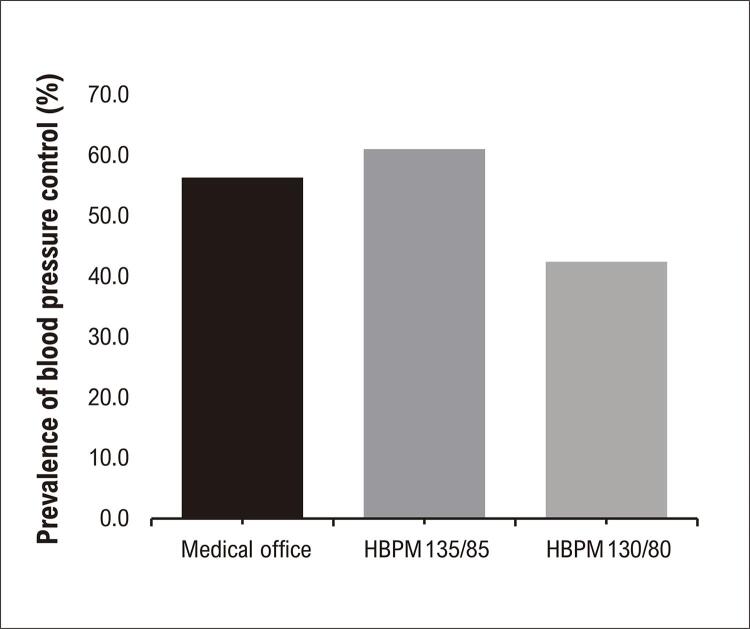

A Diretriz Brasileira de Hipertensão 202011 propôs como valores de normalidade para MRPA 130 mmHg para PAS e 80 mmHg para PAD. Observando esse novo ponte de corte, a prevalência de paciente HABNC foi de 7,6% (n = 194), HC 34,9% (n = 886), HMNC 21,8% (n = 553) e HS 35,7% (n = 907).

A Figura 3 expõe a prevalência de controle pressórico no consultório e no domicílio, observando o pontos de corte atual e o proposto anteriormente.

Figura 3. – Prevalência de controle com os novos pontos de corte para monitorização residencial da pressão arterial.

Discussão

O diagnóstico e tratamento da HA têm sido baseado principalmente na medição da PA no consultório. No entanto, a PA pode diferir consideravelmente quando medida no consultório e quando medida fora do ambiente do consultório,24 sendo que uma PA mais alta fora do consultório está associada a risco cardiovascular aumentado, independente da PA do consultório.

O presente estudo evidenciou que os indivíduos apresentaram PA mais elevada no consultório que as obtidas em domicílio. Sabe-se que as medidas da MRPA geralmente são mais baixas do que as realizadas no consultório e mais próximas da pressão média registrada durante a MAPA de 24 horas.25

A totalidade da amostra estudada obteve o número de medidas válidas na realização da MRPA. Uma MRPA com boa qualidade depende fundamentalmente das orientações fornecidas ao paciente e da utilização de um diário de medidas, que eliminam, em quase 100%, a necessidade de repetição de exames por número insuficiente de medidas.13 , 26

A MRPA fornece informações importantes sobre os níveis da PA fora do ambiente do consultório, em diferentes momentos do dia. Uma das grandes vantagens da MRPA é a identificação e acompanhamento dos fenótipos da hipertensão.7 A prevalência de HABNC e HMNC é bastante variável devido à diferença nas condições de tratamento, tipo de medida da pressão arterial fora do consultório e diferença nos critérios de corte das pressões obtidas em casa e no consultório.18

Estudo que utilizou a PA de consultório e a média da PA em casa pela manhã e pela noite e adotou os mesmos pontos de corte do presente estudo identificou prevalências mais altas (HMNC 19,0%, HABNC 19,4%, HC 23,0% e HSNC 38,7%). No referido estudo, a maioria dos pacientes com HMNC eram do sexo masculino, mais velhos, fumantes e etilistas, e frequentemente apresentavam um alto IMC, histórico de doenças cardiovasculares e mais complicações do que pacientes com HABNC ou hipertensão controlada.27

Pesquisas mundiais de controle da pressão arterial para metas recomendadas por diretrizes nacionais e internacionais revelaram consistentemente que, na prática clínica, a meta convencional de pressão arterial < 140/90 mmHg é alcançada apenas por uma minoria de pacientes.28 Uma revisão sistemática mostrou que o controle pressórico varia em torno de 28,4% nos países mais desenvolvidos e apenas 7,7% naqueles com menor grau de desenvolvimento.29 No Brasil, a taxa de controle variou de 10,4 a 35,2% em estudo de base populacional.30 No atual estudo, a taxa de controle observada foi mais alta que referida pelas outras investigações, chegando a 46,4% de controle (consultório e domicílio).

O Centro de Controle e Prevenção de Doenças observou que aproximadamente 53,5% dos americanos não alcançam a meta de PA.31 Embora o monitoramento da pressão arterial no consultório seja o padrão usual de atendimento ou padrão-ouro para diagnóstico e tratamento da hipertensão, o monitoramento da pressão arterial em casa melhora o controle da PA32 e a adesão à medicação.33 Também já foram demonstradas diversas vezes que a PA domiciliar tem poder preditivo mais forte para mortalidade e morbidade do que a PA medida no consultório.28 , 34 - 36 Nos participantes desta pesquisa, o maior controle pressórico foi o domiciliar, sendo observado principalmente no sexo feminino e na faixa etária de 49-60 anos.

Resultados de um estudo sugerem que quase um terço dos pacientes considerados com controle adequado da PA pelos critérios clínicos convencionais não tem a PA controlada quando avaliada fora do consultório. É importante ressaltar que mais de um em cada três pacientes com PA casual limítrofe tem HMNC e, portanto, tem uma PA que não é adequadamente controlada.37

Estudo brasileiro observou que as taxas de controle da PA foram de 57,0% pela medida casual e 61,3% pela MRPA (p < 0,001), com prevalência de HABNC e HMNC de 15,4 e 11,1%, respectivamente.38 Estudos publicados na última década demonstram que valores de normalidade para MRPA são mais próximos de 130/80 mmHg do que 135/85 mmHg, dando suporte à mudança nos valores de referência de MRPA para 130/80 mmHg.39

Em 2020, análise envolvendo 9.868 indivíduos brasileiros não tratados mostrou que valores de PA no consultório, de 140/90 mmHg, corresponderam a valores de 130/82 mmHg na MRPA, enquanto ao analisar 10.069 brasileiros tratados, observou-se que valores de MRPA de 131/82 mmHg são equivalentes a valores da PA no consultório de 140/90 mmHg, e que valores de referência de MRPA mais baixos do que 135/85 mmHg são mais adequados para definir a presença de comportamento anormal da PA.40

Assim, a Diretriz Brasileira de HA 202011 recomendou que os valores de anormalidade de MRPA passassem a ser ≥ 130/80 mmHg, em substituição aos valores ≥135/85 mmHg recomendados previamente pela 7a Diretriz Brasileira de HA1 e pela 6a Diretriz de Monitorização Ambulatorial da Pressão Arterial e 4ª Diretriz de Monitorização Residencial da Pressão Arterial.7 Dados de controle pressórico, com o novo ponto de corte proposto pela DBHA 2020,11 ainda não foram relatados na literatura. No referido estudo, percebe-se uma diminuição no controle domiciliar e no número de HABNC, como também um aumento no número de HMNC.

Vários estudos demonstraram que a adição da PA domiciliar ao gerenciamento rotineiro do paciente melhora a adesão ao tratamento, principalmente quando o monitoramento domiciliar da PA é associado à teletransmissão dos valores da PA mensurados pelos pacientes em casa.41 , 42 Essa é uma vantagem de suma importância, porque na vida real a baixa adesão ao tratamento é um fenômeno de proporções devastadoras,43 que pode ser considerado o principal responsável pelas baixas taxas de controle da PA que caracteriza a população hipertensa44 e torna a hipertensão ainda a primeira causa de morte no mundo.45 , 46

A obtenção de controle pressórico é crucial para evitar desfechos, como doenças cardiovasculares, insuficiência renal e derrame. Assim, diretrizes recomendam otimizar as dosagens de medicamentos ou adicionar medicamentos anti-hipertensivos até que a pressão arterial alvo seja alcançada.47 , 48 A inclusão da PA domiciliar no tratamento de pacientes hipertensos tratados favorece o efeito terapêutico de várias maneiras, ou seja, através de uma melhoria da adesão ao tratamento, evitando o supertratamento e reduzindo a inércia clínica.46 , 49

A inércia terapêutica do médico é também uma barreira para que os pacientes atinjam o controle pressórico desejado. Vários motivos podem ser subjacentes aos médicos para que não iniciem ou intensifiquem medicação anti-hipertensiva, incluindo a incerteza em relação à PA do paciente fora do consultório.50 - 53 A MRPA incentiva o atendimento centrado no paciente e melhora o controle da pressão arterial e os resultados do paciente.19

Limitações

Este estudo teve algumas limitações. A seleção dos participantes não foi estratificada no sentido de representar a população brasileira de acordo com a população de cada região, podendo assim ter superestimado a região Sudeste. Além disso, a procedência dos pacientes foi apenas de clínicas privadas, podendo não refletir a realidade dos brasileiros que utilizam o Sistema Único de Saúde.

Outra limitação foi o fato de não observar se existia uma correlação entre o controle e o número de medicamentos utilizados, assim como se outros fatores de risco influenciaram ou não o controle pressórico.

Conclusão

No presente estudo, o controle pressórico nos consultórios em uma amostra de cardiologistas brasileiros foi de 56,3%, levando em consideração a pressão verificada no interior dos consultórios; 61%, quando a PA foi obtida no domicílio; e 46,4% quando o controle foi observado tanto no consultório como no domicílio. A taxa de controle pressórico no domicílio é modificada para 42,4% utilizando-se os novos pontos de corte propostos pela DBHA 2020.

Vinculação acadêmica

Não há vinculação deste estudo a programas de pós-graduação.

Aprovação ética e consentimento informado

Este estudo foi aprovado pelo Comitê de Ética do Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Goiás sob o número de protocolo 2.985.410. Todos os procedimentos envolvidos nesse estudo estão de acordo com a Declaração de Helsinki de 1975, atualizada em 2013. O consentimento informado foi obtido de todos os participantes incluídos no estudo.

Fontes de financiamento: O presente estudo foi financiado por Indústria Farmacêutica SERVIER.

Referências

- 1.Malachias MV. 7th Brazilian Guideline of Arterial Hypertension: Presentation. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2016;107(3) Suppl 3 doi: 10.5935/abc.20160140.. 0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oliveira GMM, Mendes M, Malachias MVB, Morais J, Osni M, Filho, Coelho AS, et al. 2017 Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension in Primary Health Care in Portuguese-Speaking Countries. Rev Port Cardiol. 2017;36(11):789–798. doi: 10.1016/j.repc.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menezes TN, Oliveira ECT, Fischer MATS, Esteves GH. Prevalência e Controle da Hipertensão Arterial em Idosos: Um Estudo Populacional. Rev Port Saúde Pública. 2016;34(2):117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.rpsp.2016.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lobo LAC, Canuto R, Costa JSD, Pattussi MP. Time Trend in the Prevalence of Systemic Arterial Hypertension in Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2017;33(6):e00035316. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00035316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Análise em Saúde e Vigilância de Doenças não Transmissíveis . Vigitel Brasil 2020: Vigilância de Fatores de Risco e Proteção para Doenças Crônicas Por Inquérito Telefônico: Estimativas sobre Frequência e Distribuição Sociodemográfica de Fatores de Risco e Proteção para Doenças Crônicas nas Capitais dos 26 Estados Brasileiros e no Distrito Federal em 2020. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silva GC, Pierin AM. A Home Blood Pressure Monitoring and Control in a Group of Hypertensive Patients. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2012;46(4):922–928. doi: 10.1590/s0080-62342012000400020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nobre F, Mion D, Jr, Gomes MAM, Barbosa ECD, Rodrigues CIS, Neves MFT, et al. 6ª Diretrizes de Monitorização Ambulatorial da Pressão Arterial e 4ª Diretrizes de Monitorização Residencial da Pressão Arterial. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2018;110(5) Supl.1:1–29. doi: 10.5935/abc.20180074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Jr, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):e127–e248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Rosei EA, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 Practice Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Cardiology: ESH/ESC Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018;36(12):2284–2309. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F, Khan NA, Poulter NR, Prabhakaran D, et al. 2020 International Society of Hypertension Global Hypertension Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2020;75(6):1334–1357. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barroso WKS, Rodrigues CIS, Bortolotto LA, Mota-Gomes MA, Brandão AA, Feitosa ADM, et al. Brazilian Guidelines of Hypertension - 2020. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2021;116(3):516–658. doi: 10.36660/abc.20201238.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nobre F, Mion D., Jr Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring: Five Decades of More Light and Less Shadows. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2016;106(6):528–537. doi: 10.5935/abc.20160065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guedis AG, Sousa BDB, Marques CF, Piedra DPS, Braga JCMS, Cardoso MLG, et al. Hipertensão do Avental Branco e sua Importância de Diagnóstico. Rev Bras Hipertens. 2008;15(1):46–50. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feitosa ADM, Mota-Gomes MA, Miranda RD, Barroso WS, Barbosa ECD, Pedrosa RP, et al. Impact of 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guidelines on the Prevalence of White-Coat and Masked Hypertension: A Home Blood Pressure Monitoring Study. J Clin Hypertens. 2018 Dec;20(12):1745–1747. doi: 10.1111/jch.13422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mancia G, Parati G, Pomidossi G, Grassi G, Casadei R, Zanchetti A. Alerting Reaction and Rise in Blood Pressure During Measurement by Physician and Nurse. Hypertension. 1987;9(2):209–215. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.9.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopes PC, Coelho EB, Geleilete TJM, Nobre F. Hipertensão Mascarada. Rev Bras Hipertens. 2008;15(4):201–205. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silva GV, Ortega KT, Mion D., Jr Monitorização Residencial da Pressão Arterial (MRPA) Rev Bras Hipertens. 2008;15(4):215–219. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stergiou GS, Kario K, Kollias A, McManus RJ, Ohkubo T, Parati G, et al. Home Blood Pressure Monitoring in the 21st Century. J Clin Hypertens. 2018;20(7):1116–1121. doi: 10.1111/jch.13284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breaux-Shropshire TL, Judd E, Vucovich LA, Shropshire TS, Singh S. Does Home Blood Pressure Monitoring Improve Patient Outcomes? A Systematic Review Comparing Home and Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring on Blood Pressure Control and Patient Outcomes. Integr Blood Press Control. 2015;8:43–49. doi: 10.2147/IBPC.S49205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banegas JR, Ruilope LM, de la Sierra A, Vinyoles E, Gorostidi M, de la Cruz JJ, et al. Retraction: Banegas JR et al. Relationship between Clinic and Ambulatory Blood-Pressure Measurements and Mortality. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1509-20. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):786. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopes RD, Barroso WKS, Brandao AA, Barbosa ECD, Malachias MVB, Gomes MM, et al. The First Brazilian Registry of Hypertension. Am Heart J. 2018;205:154–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2018.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization . Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry. Geneva: WHO; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banegas JR, Ruilope LM, de la Sierra A, de la Cruz JJ, Gorostidi M, Segura J, Martell N, et al. High Prevalence of Masked Uncontrolled Hypertension in People with Treated Hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(46):3304–3312. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimbo D, Abdalla M, Falzon L, Townsend RR, Muntner P. Role of Ambulatory and Home Blood Pressure Monitoring in Clinical Practice: A Narrative Review. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(9):691–700. doi: 10.7326/M15-1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGowan N, Padfield PL. Self Blood Pressure Monitoring: A Worthy Substitute for Ambulatory Blood Pressure? J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24(12):801–806. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2010.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barroso WKS, Feitosa ADM, Barbosa ECD, Miranda RD, Brandão AA, Vitorino PVO, et al. Prevalence of Masked and White-Coat Hypertension in Pre-Hypertensive and Stage 1 Hypertensive Patients with the Use of TeleMRPA. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019;113(5):970–975. doi: 10.5935/abc.20190147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Obara T, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Asayama K, Metoki H, Inoue R, et al. Prevalence of Masked Uncontrolled and Treated White-Coat Hypertension Defined According to the Average of Morning and Evening Home Blood Pressure Value: From the Japan Home versus Office Measurement Evaluation Study. Blood Press Monit. 2005;10(6):311–316. doi: 10.1097/00126097-200512000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohkubo T, Imai Y, Tsuji I, Nagai K, Ito S, Satoh H, et al. Reference Values for 24-Hour Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring Based on a Prognostic Criterion: The Ohasama Study. Hypertension. 1998;32(2):255–259. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearney PM, Reynolds K, et al. Global Disparities of Hypertension Prevalence and Control: A Systematic Analysis of Population-Based Studies From 90 Countries. Circulation. 2016;134(6):441–450. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scala LC, Magalhães LB, Machado A. Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia . Livro texto da SBC. 2nd. São Paulo: Manole; 2015. Epidemiologia da Hipertensão Arterial Sistêmica; pp. 780–785. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital Signs: Awareness and Treatment of Uncontrolled Hypertension among Adults--United States, 2003-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:703–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cappuccio FP, Kerry SM, Forbes L, Donald A. Blood Pressure Control by Home Monitoring: Meta-Analysis of Randomised Trials. BMJ. 2004;329(7458):145. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38121.684410.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogedegbe GO, Boutin-Foster C, Wells MT, Allegrante JP, Isen AM, Jobe JB, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Positive-Affect Intervention and Medication Adherence in Hypertensive African Americans. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(4):322–326. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohkubo T, Asayama K, Kikuya M, Metoki H, Hoshi H, Hashimoto J, et al. How Many Times Should Blood Pressure be Measured at Home for Better Prediction of Stroke Risk? Ten-Year Follow-Up Results from the Ohasama Study. J Hypertens. 2004;22(6):1099–1104. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200406000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bobrie G, Chatellier G, Genes N, Clerson P, Vaur L, Vaisse B, et al. Cardiovascular Prognosis of “Masked Hypertension” Detected by Blood Pressure Self-Measurement in Elderly Treated Hypertensive Patients. JAMA. 2004;291(11):1342–1349. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.11.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohkubo T, Asayama K, Kikuya M, Metoki H, Obara T, Saito S, et al. Prediction of Ischaemic and Haemorrhagic Stroke by Self-Measured Blood Pressure at Home: The Ohasama Study. Blood Press Monit. 2004;9(6):315–320. doi: 10.1097/00126097-200412000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andalib A, Akhtari S, Rigal R, Curnew G, Leclerc JM, Vaillancourt M, et al. Determinants of Masked Hypertension in Hypertensive Patients Treated in a Primary Care Setting. Intern Med J. 2012;42(3):260–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2010.02407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barroso WKS, Feitosa ADM, Barbosa ECD, Brandão AA, Miranda RD, Vitorino PVO, et al. Treated Hypertensive Patients Assessed by Home Blood Pressure Telemonitoring. TeleMRPA Study. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2021;117(3):520–527. doi: 10.36660/abc.20200073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feitosa ADM, Mota-Gomes MA, Nobre F, Mion D, Jr, Paiva AMG, et al. What are the Optimal Reference Values for Home Blood Pressure Monitoring? Arq Bras Cardiol. 2021;116(3):501–503. doi: 10.36660/abc.20201109.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feitosa ADM, Mota-Gomes MA, Barroso WS, Miranda RD, Barbosa ECD, Pedrosa RP, et al. Correlation between Office and Home Blood Pressure in Clinical Practice: A Comparison with 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Hypertension Guidelines recommendations. J Hypertens. 2020;38(1):179–181. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parati G, Omboni S, Albini F, Piantoni L, Giuliano A, Revera M, et al. Home Blood Pressure Telemonitoring Improves Hypertension Control in General Practice. The TeleBPCare study. J Hypertens. 2009;27(1):198–203. doi: 10.1097/hjh.0b013e3283163caf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McManus RJ, Mant J, Bray EP, Holder R, Jones MI, Greenfield S, et al. Telemonitoring and Self-Management in the Control of Hypertension (TASMINH2): A Randomised Controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9736):163–172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60964-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corrao G, Zambon A, Parodi A, Poluzzi E, Baldi I, Merlino L, et al. Discontinuation of and Changes in Drug Therapy for Hypertension among Newly-Treated Patients: A Population-Based Study in Italy. J Hypertens. 2008;26(4):819–824. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f4edd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Whelton PK, He J. Worldwide Prevalence of Hypertension: A Systematic Review. J Hypertens. 2004;22(1):11–19. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200401000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Hoorn SV, Murray CJ, Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Group Selected Major Risk Factors and Global and Regional Burden of Disease. Lancet. 2002;360(9343):1347–1360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Agarwal R, Bills JE, Hecht TJ, Light RP. Role of Home Blood Pressure Monitoring in Overcoming Therapeutic Inertia and Improving Hypertension Control: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hypertension. 2011;57(1):29–38. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.160911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. 2014 Evidence-Based Guideline for the Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Report from the Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) JAMA. 2014;311(5):507–520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mancia G, Parati G. Home Blood Pressure Monitoring: A Tool for Better Hypertension Control. Hypertension. 2011;57(1):21–23. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willock R, Miller JB, Mohyi M, Abuzaanona A, Muminovic M, Levy PD. Therapeutic Inertia and Treatment Intensification. 4Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20(1) doi: 10.1007/s11906-018-0802-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levy PD, Willock RJ, Burla M, Brody A, Mahn J, Marinica A, et al. Total Antihypertensive Therapeutic Intensity Score and Its Relationship to Blood Pressure Reduction. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2016;10(12):906–916. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Faria C, Wenzel M, Lee KW, Coderre K, Nichols J, Belletti DA. A Narrative Review of Clinical Inertia: Focus on Hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2009;3(4):267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holland N, Segraves D, Nnadi VO, Belletti DA, Wogen J, Arcona S. Identifying Barriers to Hypertension Care: Implications for Quality Improvement Initiatives. Dis Manag. 2008;11(2):71–77. doi: 10.1089/dis.2008.1120007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]