Abstract

The outer surface protein C (OspC) and the internal 14-kDa flagellin fragment of strain GeHo of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto were expressed as recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli and were purified for use in an immunoglobulin M (IgM) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (OspC–14-kDa antigen ELISA). No hint at disturbing protein-protein interferences, which might influence the availability of immunoreactive epitopes, was found when the recombinant antigens were combined in the ELISA. The recombinant OspC–14-kDa antigen ELISA was compared to a commercial IgM ELISA that used a detergent cell extract from Borrelia afzelii PKo as the antigen. According to the manufacturer’s information, the cell extract contains, in addition to other antigens, the following diagnostically relevant antigens: the 100-kDa (synonyms, 93- and 83-kDa antigens), 41-kDa, OspA, OspC, and 17-kDa antigens. The specificity was adjusted to 95% on the basis of data for 154 healthy controls. On testing of 104 serum samples from patients with erythema migrans (EM), the sensitivity of the recombinant ELISA (46%) for IgM antibodies was similar to that of the commercial ELISA (45%). However, when 42 serum samples from patients with polyclonal B-cell stimulation due to an Epstein-Barr virus infection were tested, false-positive reactions were significantly less frequent in the recombinant ELISA (10%) than in the whole-cell-extract ELISA (23%). OspC displays sequence heterogeneity of up to 40% according to the genomospecies. However, when the reactions of serum specimens from controls and EM patients with OspC from representative strains of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (strain GeHo) and B. afzelii (strain PKo) were compared in an ELISA, almost no differences in specificity and sensitivity were seen. This demonstrates that the sera predominantly recognize the common epitopes of OspC tested in this study. In conclusion, we suggest that the OspC–14-kDa antigens ELISA is a suitable test for the detection of an IgM response in early Lyme disease.

Serological testing is the most common way of confirming a clinical diagnosis of Lyme disease (12, 29). Indirect fluorescent-antibody staining or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) with whole cells or extracts thereof as antigens have adequate sensitivity but are affected by a lack of specificity (3, 7, 21). This is due mainly to the reactivity of conserved antigens like heat shock proteins in the range of 60 to 70 kDa and parts of the 41-kDa flagellin, which cross-react with those of other bacterial species (4, 19). Western blotting (WB) performed with whole-cell lysates or recombinant antigens of Borrelia burgdorferi offer the advantage of being able to differentiate between specific and nonspecific bands. Some investigators claim that WB with either native (5, 18, 31, 36, 37) or recombinant (33, 34) antigens is sufficiently sensitive and specific. WB on the other hand, is a nonquantitative method and difficult to standardize, resulting in some controversy on interpretation criteria (5, 6, 14, 18, 38). Results are subjective, particularly in cases of faint bands. Comigration of different antigens by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) as well as the potential loss of conformational epitopes are limitations of immunoblotting. ELISAs performed with isolated borrelial antigens showed increased specificity. Hansen et al. (13) established an ELISA with flagella isolated from B. burgdorferi. That ELISA appears to be, in terms of diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, superior to WB (13, 16, 22). We have reported on a highly specific borrelia immunoglobulin G (IgG) ELISA performed with recombinant p83; this assay has value for the serodiagnosis of advanced-stage Lyme disease (26). Such assays are appropriate alternatives to WB because they are quantitative and easy to standardize. In addition, they can be performed more conveniently and less expensively than WB.

In the early stages of Lyme disease, IgM antibodies are predominantly reactive with the outer surface protein C (OspC) or the flagellin of B. burgdorferi, or both (2, 5, 6, 9, 36). In some of these patients the antibody response is also directed against the 39-kDa protein (6, 14). Epitope mapping of the B. burgdorferi flagellin indicated that the internal region of the molecule comprises the variable, genus-specific immunodominant domains (10, 17). Rasiah et al. (25) purified and characterized from this central region a tryptic 14-kDa peptide which reduces cross-reactivity in immunoblots and ELISA.

There is broad consensus in the literature that OspC is a specific and an IgM-sensitive antigen that can be used for testing (2, 6, 20, 23, 34). It displays sequence identity ranging from 60.5 to 77% among the three delineated genomospecies (15, 30, 35). The objective of this study was to establish a combined IgM ELISA with recombinant OspC and the internal 14-kDa flagellin fragment. Its suitability for routine diagnostic use was evaluated, and it was compared to a proven commercial IgM ELISA that uses a detergent cell extraction from Borrelia afzelii as the antigen. In addition, we tested whether recombinant OspCs from two different borrelial genomospecies produced in the IgM ELISA discrepant results due to sequence heterogeneity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (strain GeHo; passage number, 28; provided by K. Pelz, Freiburg, Germany) was grown in modified BSK medium at 33°C for 4 days. Spirochetes were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 30 min at 20°C, and isolation of DNA was done as described previously (1). Escherichia coli Tb1 was used for transformation and expression of the recombinant OspC. E. coli Hb101 was used for expression of recombinant flagellin.

Construction of recombinant OspC.

Recombinant OspC was constructed as a nonfusion protein by methods described previously for other borrelial antigens (24). The oligonucleotides used for the amplification of the entire open reading frame of OspC by PCR were derived from published sequences (8, 30) (sense primer, 5′-AGGCACAAATCCATGGAAAAGAATACA-3′ [the NcoI site is underlined]; antisense primer, 5′-CTTATAATATGGATCCTATTAAGGTTT-3′ [the BamHI site is underlined]). PCR products were ligated into the expression vector pJLA602 (medac) by standard methods.

Expression and purification of recombinant OspC from B. burgdorferi GeHo.

E. coli Tb1 expressing recombinant OspC was grown overnight in Luria broth medium (GIBCO) containing ampicillin at 100 μg/ml. The culture was then diluted 1:50 in the same medium and was grown for an additional 3 h at 37°C. The expression of OspC was induced by raising the temperature to 42°C for 8 h. The cells were then centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 15 min and washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline. After the final wash, the cells were resuspended in buffer containing 8 M urea, 150 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), and protease inhibitors (5 mM benzamidine, 5 mM sodium tetrathionate, 5 mM EDTA, 1 μM leupeptin), stirred for 2 h at 4°C, and centrifuged at 27,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. OspC was separated from the supernatant by gel filtration on Superdex 200 HR (Pharmacia). Fractions containing OspC were dialyzed against buffer A, which contained 20 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and protease inhibitors (see above). Final purification was achieved by anion-exchange chromatography on Resource Q (Pharmacia). Elution buffer B was the same as start buffer A except that buffer B contained 1 M NaCl. OspC eluted at 10% buffer B. The protein content for the OspC antigen produced by this method was about 100 μg/ml. It was determined with the Coomassie Plus Protein Assay Reagent (Pierce).

Purification of recombinant tryptic 14-kDa fragment.

Purification of the recombinant tryptic 14-kDa fragment from B. burgdorferi was done as described previously (25). Briefly, the 41-kDa flagellin expressed by E. coli Hb101 was extracted with 8 M urea and was enriched by anion-exchange chromatography (DEAE-Cellulose; Serva). Enriched flagellin was precipitated by dialysis against distilled water. Pure 41-kDa flagellin was obtained following cation-exchange chromatography (SP-Sephadex C50; Pharmacia). Trypsin (sequencing grade; Boehringer Mannheim) digestion of the 41-kDa flagellin yielded the 14-kDa flagellin peptide, which was finally isolated by gel filtration on Superdex 75 (Pharmacia).

ELISA.

ELISA was done by standard methods. Each well of 96-well flat-bottom plates (Greiner) was coated at 4°C overnight with 100 μl of purified recombinant OspC (1.0 μg/ml) and/or recombinant 14-kDa-fragment (2.0 μg/ml) diluted in coating buffer (15 mM Na2CO3, 35 mM NaHCO3 [pH 9.5]). After washing with 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20 in washing buffer (0.15 M NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM KH2PO4), the plates were incubated with patient sera diluted 1:200 in dilution buffer (washing buffer containing 1% [wt/vol] Pentex [Bayer], 2% [vol/vol] Tween 20, and 0.5% [vol/vol] Treponema phagedenis sonicate [BAG]) for 1 h at 37°C. The plates were washed again. Bound antibodies were detected with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgM (DAKO), diluted 1:1,000 in the same buffer used for the sera, and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. After a third washing step, substrate solution (0.4 mg of ortho-phenylendiamine/ml; tablets; DAKO) in substrate buffer (20 mM Na2HPO4, 100 mM KH2PO4) was added, and the mixture was incubated for 15 min in a dark chamber at 4°C. The reaction was stopped with 2 M H2SO4, and the optical density (OD) was read at 492 nm with an SLT reader (type 340 ATC). The cutoff for optical density readings at OD492 was set 2 standard deviation above the mean for 154 samples from healthy controls.

For comparison, sera were tested in a commercial IgM ELISA with a detergent extraction from B. afzelii PKo as the antigen. In this ELISA sera were preadsorbed with rheumatoid factor adsorbens (sheep antibodies directed against the human IgG Fc fragment) as well as with T. phagedenis sonicate (ready to use and included in the sample buffer of the commercial test kit). The ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. In order to get comparable results, we evaluated the commercial ELISA by the same methods described below for the recombinant ELISA.

Adsorption of sera.

Serum samples were prediluted 1:20 in dilution buffer (containing 0.5% [vol/vol]) T. phagedenis NICHOLS sonicate obtained from infected rabbits [BAG]). The same volume of RF-Absorbent (sheep antibodies directed against the human IgG Fc fragment; Behring) was added. After the solution was mixed thoroughly, it was incubated for 15 min at room temperature and was finally diluted (up to 1:200) with dilution buffer as mentioned above.

SDS-PAGE.

SDS-PAGE was performed by a method modified from that of Schägger and von Jagow (28) with a 12% separating gel and a 4% stacking gel. The amounts of recombinant proteins (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto GeHo) separated by SDS-PAGE were as follows: 14-kDa flagellin fragment, 260 μg per gel; OspC, 80 μg per gel.

Immunoblotting.

Immunoblotting was done as described by Towbin et al. (32). Sera were diluted 1:50 for the detection of IgM antibodies. Immunodetection was done with peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-human IgM (Dianova; diluted 1:500 in 10% [wt/vol] skim milk in phosphate-buffered saline), and diaminobenzidine (Sigma) was used as the substrate. A monoclonal antibody (monoclonal antibody BBpCA3) was used to verify reactivity to recombinant OspC (27). A polyclonal rabbit hyperimmune serum (K270; raised against the purified 14-kDa flagellin fragment) (25) was used to confirm reactivity to the 14-kDa flagellin fragment by immunoblotting.

Patient serum samples.

One hundred four serum samples from patients with physician-documented erythema migrans (EM) were obtained from the departments of dermatology of the university hospitals of Freiburg and Munich. To estimate the cutoff values of the ELISAs, 154 serum samples from local students with no current clinical symptoms and without a prior history of Lyme disease were also tested. To investigate the cross-reactivity of OspC with antibodies induced by polyclonal stimulation due to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, 44 serum samples from patients with acute EBV infection were tested. Additionally, 44 samples from patients with a history of syphilis (T. pallidum hemagglutination assay positive) were tested.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequence of the OspC gene of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto B31 has been deposited in the EMBL database and given the accession no. X73622 (30). The sequence of the OspC gene of B. afzelii PKo has been deposited in the EMBL database and given the accession no. X62162 (8).

RESULTS

The cutoff values for positive results were adjusted to a diagnostic specificity of 95%, estimated by examination of 154 serum samples from local students with no current clinical symptoms and with no prior history of Lyme disease. In the IgM ELISAs with OspC of strain GeHo and OspC of strain PKo, cutoff values were 0.42 and 0.26, respectively. Sensitivities were 38% (IgM ELISA with OspC of GeHo) and 36% (IgM ELISA with OspC of PKo) for the group of 104 patients with EM. Indices (ratio of the OD to the cutoff value) for samples with clearly discrepant results by both ELISAs are given in Table 1. An index of >1 indicates a positive result.

TABLE 1.

Indices for sera with clearly discrepant results by the ELISA with recombinant OspC from B. burgdorferi GeHo and recombinant OspC from B. afzelli PKo

| Serum sample no.a | Index by ELISA with

|

|

|---|---|---|

| OspC from GeHo | OspC from PKo | |

| 5 | 0.7 | 3.4 |

| 14 | 2.8 | 0.6 |

| 19 | 1.2 | 0.3 |

| 61 | 1.1 | 0.2 |

The sera were from patients with EM.

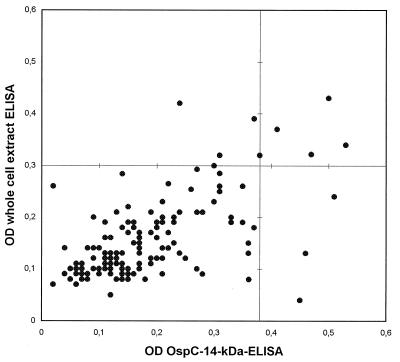

On combining OspC of GeHo and the 14-kDa flagellin fragment in an ELISA, the best differentiation between positive and negative sera was achieved when the microtiter plates were coated with the antigens at concentrations of 1.0 μg/ml for OspC and 2.0 μg/ml for the 14-kDa peptide. On testing of sera from 154 healthy controls, the cutoff OD value at a specificity of 95% was 0.38. In the commercial ELISA the cutoff OD was 0.30 when the assay was evaluated as described for the OspC–14-kDa antigen ELISA. The OD readings for the controls are presented in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

OD values for 154 serum samples from healthy controls by the recombinant OspC–14-kDa antigen IgM ELISA and by the whole-cell-extract IgM ELISA. Diagnostic cutoff OD values are marked as a horizontal line (whole-cell-extract IgM ELISA = 0.3) and a vertical line (OspC–14-kDa antigen IgM ELISA = 0.38).

To evaluate the reproducibility of the recombinant ELISA, seven serum samples (two with a clearly positive result [OD of 1.5], three with a weakly positive result [OD in the range of 0.4 to 0.5], and two with a negative result [OD of <0.2) were tested six times. The reproducibilities of the ODs from run to run were ± 10%. The study was performed without involving the definition of a borderline range. However, in routine diagnostic use, when clinical decisions depend on the results of the ELISA, the use of a borderline range is essential.

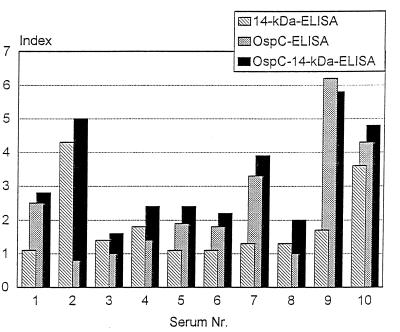

In order to investigate possible protein-protein interference between the proteins used in combination in the recombinant ELISA, we examined 40 preselected serum samples from patients with various manifestations of Lyme disease (n = 25 patients with EM; n = 12 patients with neuroborreliosis; n = 3 patients with acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans). They revealed a positive result in OspC IgM ELISA (30 of 40 serum samples) and/or in the 14-kDa antigen IgM ELISA (27 of 40 serum samples). A total of 39 of 40 (98%) of the serum samples were positive and 1 (2%) serum sample was borderline in the combined OspC–14-kDa antigen ELISA. In addition, we compared the indices estimated with the antigens used singly in the ELISA with that estimated with the antigens used in combination ELISA. Results for 10 representative serum samples are given in Fig. 2. There is a clear additive effect regarding the indices obtained by the OspC–14-kDa antigen ELISA compared to those obtained by ELISAs performed with each antigen alone.

FIG. 2.

Indices (ratios of ODs and cutoff) for representative sera by OspC IgM ELISA, 14-kDa antigen IgM ELISA, and OspC–14-kDa antigen IgM ELISA.

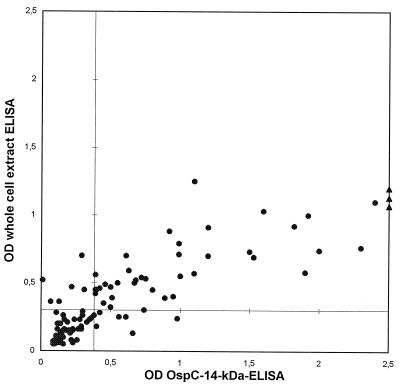

Sensitivity (defined as the number of correct positive results divided by the total number of serum samples from Lyme disease patients) was estimated by testing 104 serum samples from patients with a clinical diagnosis of EM. By the recombinant OspC–14-kDa antigen IgM ELISA, 48 (46%) of 104 serum samples were positive, whereas by the commercial IgM ELISA, 47 (45%) of the serum samples were positive (Fig. 3). The mean of the differences between the ODs obtained by both ELISAs indicated significantly higher ODs by the recombinant ELISA (mean OD, 0.98) than by the whole-cell-extract ELISA (mean OD, 0.64) (P < 0.0001; paired Wilcoxon rank test).

FIG. 3.

OD values for 104 serum samples from patients with EM. Diagnostic cutoff OD values are marked as a horizontal line (whole-cell extract IgM ELISA = 0.3) and a vertical line (OspC–14-kDa antigen IgM ELISA = 0.38).

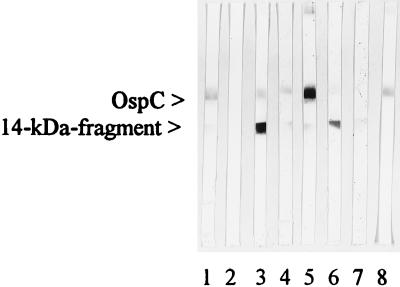

To investigate false-positive reactions in both ELISAs with cross-reactive antibodies due to an EBV infection, we tested 42 serum samples from patients with acute EBV infection. Four (10%) revealed a positive result by the recombinant ELISA and 10 (24%) were positive by the commercial ELISA (P < 0.002; chi-square test). Furthermore, we screened a larger panel of EBV-positive sera by the recombinant ELISA. A total of 11 positive serum samples were also tested by immunoblotting with recombinant OspC and the 14-kDa antigen (Fig. 4). Three serum samples revealed antibodies to both recombinant antigens. Six serum samples showed a positive result exclusively with the 14-kDa band, and two serum samples reacted only with the OspC band.

FIG. 4.

IgM immunoblots. The reactivities of six serum samples with recombinant OspC and the 14-kDa flagellin fragment of B. burgdorferi GeHo as antigens are presented. Lanes: 1, positive control; 2, negative control; 3, 7, and 8, sera from patients with a history of syphilis; 4, 5, and 6, sera from patients with EBV infection. Lanes 3, 4, 5, and 6 display both the OspC and the 14-kDa antigen bands with various intensities; lane 7 shows only a weak 14-kDa antigen band; lane 8 reveals only an OspC band.

On testing of 44 serum samples from patients with a history of syphilis, 5 serum samples (11%) were positive by each ELISA. Of these, four serum samples were positive by both ELISAs. In addition, 12 serum samples from healthy controls and from patients with syphilis which were reactive in the OspC–14-kDa antigen ELISA were also tested by immunoblotting with recombinant OspC and the 14-kDa antigen (Fig. 4 shows the patterns obtained with six patient serum samples). Seven serum samples reacted with both recombinant antigens, four serum samples recognized only the 14-kDa band, and one serum sample reacted exclusively with OspC.

DISCUSSION

According to former studies, OspC and the internal flagellin fragment are the most sensitive and specific antigens for the detection of IgM antibodies in patients with early Lyme disease (2, 34). The aim of this study was to establish a combined IgM ELISA with recombinant OspC and the internal flagellin fragment from B. burgdorferi as antigens. In addition, we investigated whether use of recombinant OspCs from two different borrelial genomospecies in an ELISA would increase the sensitivity of IgM assessment in Lyme serology.

On comparing the immunoreactivities of recombinant OspC from two different genomospecies in an IgM ELISA (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and B. afzelii), very few discrepancies were noted. The low level of serological heterogeneity of both OspCs by ELISA is a surprising finding, particularly if one considers the low degree of amino acid identity between the two genomospecies of 61.5 to 74.0% (15, 30). On the other hand, our results are in agreement with those of a study by Wilske et al. (34). Those investigators observed that IgM antibodies from patients with neuroborreliosis mainly recognized epitopes of the recombinant OspC, which were conserved among the three genomospecies. According to our data, sensitivity would not increase significantly by combining OspC from strain PKo and GeHo in ELISA. Thus, we used only OspC from strain GeHo in the combined IgM ELISA.

In order to detect possible protein-protein interference between recombinant antigens in ELISA, we tested 40 preselected serum samples positive either in the ELISA with OspC from GeHo or in the 14-kDa antigen IgM ELISA. With the exception of one serum sample (which showed a borderline OD), all sera revealed higher ODs by the ELISA with both antigens, indicating a higher sensitivity of the ELISA with both antigens compared to those of ELISAs with the single antigens. This can be further confirmed when the indices obtained by the three ELISAs are compared (Fig. 2). Most sera showed an increased index by the combined OspC–14-kDa antigen ELISA. Only for serum sample 9 did the index of the combined ELISA seem to be slightly lower compared to the index of the 14-kDa ELISA. Both indices, however, represent extremely high ODs. It is possible that slight differences in the indices for highly positive sera (serum samples 2, 9, and 10) are not significant because of the nonlinear dependence of high ODs (>2.0) on the serum dilution. Nevertheless, from these data it can be concluded that there is an additive effect regarding the ODs of the single-antigen ELISAs when both antigens are combined in an ELISA. The additive effect regarding the ODs in the combination ELISA might be explained by a broader spectrum of relevant epitopes per microtiter well compared to those for the ELISAs performed with single antigens. Furthermore, we infer that there are no disturbing interferences between the recombinant antigens used in the ELISA; such interference would influence the availability of immunoreactive sites.

The incidence of false-positive reactions by cross-reactive antibodies due to an EBV infection was markedly high in the commercial ELISA, with 23% positive results. The recombinant ELISA revealed only 10% positive results for this group of serum specimens. Increased cross-reactivity of EBV-positive sera in the commercial ELISA is not surprising because B. burgdorferi sensu lato contains many cross-reactive antigens like conserved parts of the 41-kDa flagellin, which share epitopes with other bacterial species (4, 19).

The 46% sensitivity of the recombinant OspC–14-kDa antigen ELISA at the level of 95% specificity was similar to the sensitivity of the commercial ELISA. Considering the results presented in Fig. 3, the high concordance of the OD values for single serum samples by both ELISAs can be observed. There are no discrepancies regarding positive sera with ODs of more than 1.0 and 0.7 by the recombinant and the whole-cell-extract ELISAs, respectively. This indicates that the sensitivity of an ELISA with only two recombinant antigens is at least as good as the sensitivity of a whole-cell-extract ELISA, while the specificity of the recombinant ELISA is improved. Gerber et al. (11) observed a clearly improved sensitivity of a recombinant OspC-IgM ELISA compared to that of a whole-cell-extract IgM ELISA. OspC is known to be expressed in various amounts by different borrelial strains in culture (30). We suggest that the discrepancies in the sensitivities of IgM ELISAs performed with whole-cell extracts mainly depend on the various levels of expression of OspC.

The high concordance of ODs by both ELISAs with sera from patients with syphilis was a surprising result. We expected a clearly improved specificity of the recombinant ELISA because of suspected cross-reactive epitopes in the whole-cell-extract ELISA. This observation might be explained by the quite effective adsorption of cross-reactive antibodies with the T. phagedenis sonicate in the commercial ELISA. When the recombinant ELISA was performed without preadsorption of the sera with T. phagedenis sonicate, no significant effect on the specificity and the sensitivity was observed (data not shown). This suggests that high concentrations of cross-reactive epitopes do not exist between T. phagedenis and either of the recombinant antigens tested in this study. On the other hand, these data show that preadsorption of sera with T. phagedenis sonicate does not eliminate all cross-reactive antibodies.

By additionally testing false-positive sera (sera from controls and patients with EBV infection and syphilis) by immunoblotting and by ELISAs performed with single antigens, these sera were reactive with the 14-kDa antigen and with OspC. Cross-reactive antibodies had a tendency to be slightly more frequently directed against the 14-kDa antigen than against OspC. These data are in line with those presented in previous reports (20, 34).

As can be seen in Fig. 3 the mean of the positive ODs was significantly higher by the recombinant ELISA than by the whole-cell-extract ELISA. From these data, one may conclude that the ability to discriminate between real-positive and real-negative sera is superior for the recombinant ELISA due to a presumed higher concentration of relevant epitopes per microtiter well.

There are several reports on the use of recombinant OspC for the serological diagnosis of Lyme disease (11, 23, 33, 34). This, however, is the first study in which the whole sequence of recombinant OspC is used as a nonfusion protein in combination with the internal flagellin fragment in an ELISA. Padula et al. (23) reported on the results of studies with recombinant OspC expressed as a fusion protein. Tests with sera from 74 individuals with culture-confirmed EM revealed a sensitivity of approximately 65% (23), which was clearly higher than that in our study. This discrepancy could be explained by differences in evaluation of the cutoff OD value and by variations in the criteria used for case definition.

In conclusion, the recombinant OspC–14-kDa antigen IgM ELISA is at least as sensitive as a whole-cell-extract ELISA and was revealed to have significantly higher positive ODs than the whole-cell-extract ELISA. This might result in an improved ability to discriminate between true-positive and true-negative sera. In addition, the recombinant ELISA compared favorably in specificity to the whole-cell-extract ELISA on the testing of sera from patients with EBV infection. We suggest that the OspC–14-kDa antigen IgM ELISA is a suitable test for the serodiagnosis of early Lyme disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Bundesministerium für Forschung und Technik (grant 01KI89098).

We thank G. Bauer for kindly providing the sera from patients with EBV. We are indebted to S. Batsford for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adam T, Gassmann G S, Rasiah C, Göbel U B. Phenotypic and genotypic analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi isolates from various sources. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2579–2585. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2579-2585.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguero-Rosenfeld M E, Nowakowski J, McKenna D F, Carbonaro C A, Wormser G P. Serodiagnosis in early Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3090–3095. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.12.3090-3095.1993. . (Erratum, 32:860, 1994.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbour A G. Laboratory aspects of Lyme borreliosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1988;1:399–414. doi: 10.1128/cmr.1.4.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruckbauer H R, Preac-Mursic V, Fuchs R, Wilske B. Cross-reactive proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;11:224–232. doi: 10.1007/BF02098084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dressler F, Whalen J A, Reinhardt B N, Steere A C. Western blotting in the serodiagnosis of Lyme disease. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:392–400. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.2.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engstrom S M, Shoop E, Johnson R C. Immunoblot interpretation criteria for serodiagnosis of early Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:419–427. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.419-427.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feder H M, Jr, Gerber M A, Luger S W, Ryan R W. False positive serologic tests for Lyme disease after varicella infection. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1886–1887. doi: 10.1056/nejm199112263252615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuchs R, Jauris S, Lottspeich F, Preac-Mursic V, Wilske B, Soutschek E. Molecular analysis and expression of a Borrelia burgdorferi gene encoding a 22 kDa protein (pC) in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:503–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fung B P, McHugh G L, Leong J M, Steere A C. Humoral immune response to outer surface protein C of Borrelia burgdorferi in Lyme disease: role of the immunoglobulin M response in the serodiagnosis of early infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3213–3221. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3213-3221.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gassmann G S, Jacobs E, Deutzmann R, Gobel U B. Analysis of the Borrelia burgdorferi GeHo fla gene and antigenic characterization of its gene product. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1452–1459. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.4.1452-1459.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerber M A, Shapiro E D, Bell G L, Sampieri A, Padula S J. Recombinant outer surface protein C ELISA for the diagnosis of early Lyme disease. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:724–727. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen K. Laboratory diagnostic methods in Lyme borreliosis. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:407–414. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(93)90097-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen K, Hindersson P, Pedersen N S. Measurement of antibodies to the Borrelia burgdorferi flagellum improves serodiagnosis in Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:338–346. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.2.338-346.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofmann H, Bruckbauer H R. Abstracts of the VIth International Conference on Lyme Borreliosis. 1994. Diagnostic value of recombinant protein-immunoblot compared to purified flagellum-ELISA in early Lyme borreliosis, poster PO99T. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jauris-Heipke S, Fuchs R, Motz M, Preac-Mursic V, Schwab E, Soutschek E, Will G, Wilske B. Genetic heterogeneity of the genes coding for the outer surface protein C (OspC) and the flagellin of Borrelia burgdorferi. Med Microbiol Immunol (Berlin) 1993;182:37–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00195949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlsson M. Western immunoblot and flagellum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2148–2150. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.2148-2150.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luft B J, Dunn J J, Dattwyler R J, Gorgone G, Gorevic P D, Schubach W H. Cross-reactive antigenic domains of the flagellin protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. Res Microbiol. 1993;144:251–257. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(93)90009-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma B, Christen B, Leung D, Vigo-Pelfrey C. Serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis by Western immunoblot: reactivity of various significant antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:370–376. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.2.370-376.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magnarelli L A, Anderson J F, Johnson R C. Cross-reactivity in serological tests for Lyme disease and other spirochetal infections. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:183–188. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magnarelli L A, Fikrig E, Padula S J, Anderson J F, Flavell R A. Use of recombinant antigens of Borrelia burgdorferi in serologic tests for diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:237–240. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.237-240.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magnarelli L A, Meegan J M, Anderson J F, Chappell W A. Comparison of an indirect fluorescent-antibody test with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for serological studies of Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;20:181–184. doi: 10.1128/jcm.20.2.181-184.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olsson I, von Stedingk L V, Hanson H S, von Stedingk M, Asbrink E, Hovmark A. Comparison of four different serological methods for detection of antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in erythema migrans. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 1991;71:127–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Padula S J, Dias F, Sampieri A, Craven R B, Ryan R W. Use of recombinant OspC from Borrelia burgdorferi for serodiagnosis of early Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1733–1738. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1733-1738.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rasiah C, Rauer S, Gassmann G S, Vogt A. Use of a hybrid protein consisting of the variable region of the Borrelia burgdorferi flagellin and part of the 83-kDa protein as antigen for serodiagnosis of Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1011–1017. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.1011-1017.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rasiah C, Schiltz E, Reichert J, Vogt A. Purification and characterization of a tryptic peptide of Borrelia burgdorferi flagellin, which reduces cross-reactivity in immunoblots and ELISA. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:147–154. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-1-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rauer S, Kayser M, Neubert U, Rasiah C, Vogt A. Establishment of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using purified recombinant 83-kilodalton antigen of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto and Borrelia afzelii for serodiagnosis of Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2596–2600. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2596-2600.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rauer S, Schiltz E, Rasiah C, Vogt A. The outer surface protein C (OspC) from Borrelia burgdorferi can appear as a dimeric molecule in Western blot. J Spirochetal Tick-Borne Dis. 1996;3:105–108. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schägger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stiernstedt G, Dattwyler R, Duray P H, Hansen K, Jirous J, Johnson R C, Karlsson M, Preac-Mursic V, Schwan T G. Diagnostic tests in Lyme borreliosis. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1991;77:136–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Theisen M, Frederiksen B, Lebech A M, Vuust J, Hansen K. Polymorphism in ospC gene of Borrelia burgdorferi and immunoreactivity of OspC protein: implications for taxonomy and for use of OspC protein as a diagnostic antigen. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2570–2576. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2570-2576.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tilton R C. Laboratory aids for the diagnosis of Borrelia burgdorferi infection. Jo Spirochetal Tick-Borne Dis. 1994;1:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Towbin H, Staehelin H, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilske B, Fingerle V, Herzer P, Hofmann A, Lehnert G, Peters H, Pfister H W, Preac-Mursic V, Soutschek E, Weber K. Recombinant immunoblot in the serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Comparison with indirect immunofluorescence and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Med Microbiol Immunol (Berlin) 1993;182:255–270. doi: 10.1007/BF00579624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilske B, Fiongerle V, Preac-Mursic V, Jauris-Heipke S, Hofmann A, Loy H W, Pfister, Rossler D, Soutschek E. Immunoblot using recombinant antigens derived from different genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Med Microbiol Immunol (Berlin) 1994;183:43–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00193630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V, Jauris S, Hofmann A, Pradel I, Soutschek E, Schwab E, Will G, Wanner G. Immunological and molecular polymorphisms of OspC, an immunodominant major outer surface protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2182–2191. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2182-2191.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V, Schierz G, Liegl G, Gueye W. Detection of IgM and IgG antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi using different strains as antigen. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg Suppl. 1989;18:299–399. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zöller L, Burkard S, Schafer H. Validity of Western immunoblot band patterns in the serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:174–182. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.1.174-182.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zöller L, Cremer J, Faulde M. Western blot as a tool in the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Electrophoresis. 1993;14:937–944. doi: 10.1002/elps.11501401149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]