Abstract

Background.

The European region, certified as polio free in 2002, had recent wild poliovirus (WPV) introductions, resulting in a major outbreak in Central Asian countries and Russia in 2010 and in current widespread WPV type 1 circulation in Israel, which endangered the polio-free status of the region.

Methods.

We assessed the data on the major determinants of poliovirus transmission risk (population immunity, surveillance, and outbreak preparedness) and reviewed current threats and measures implemented in response to recent WPV introductions.

Results.

Despite high regional vaccination coverage and functioning surveillance, several countries in the region are at high or intermediate risk of poliovirus transmission. Coverage remains suboptimal in some countries, subnational geographic areas, and population groups, and surveillance (acute flaccid paralysis, enterovirus, and environmental) needs further strengthening. Supplementary immunization activities, which were instrumental in the rapid interruption of WPV1 circulation in 2010, should be implemented in high-risk countries to close population immunity gaps. National polio outbreak preparedness plans need strengthening. Immunization efforts to interrupt WPV transmission in Israel should continue.

Conclusions.

The European region has successfully maintained its polio-free status since 2002, but numerous challenges remain. Staying polio free will require continued coordinated efforts, political commitment and financial support from all countries.

Keywords: poliomyelitis, polio eradication, European region, polio-free status

The European region of the World Health Organization (WHO) had the last indigenous case of poliomyelitis in 1998 and was certified as polio free by the European Regional Certification Commission for Poliomyelitis Eradication (RCC) in 2002 [1]. The global efforts to interrupt wild poliovirus (WPV) transmission in the remaining areas of circulation have been intensified since the World Health Assembly declared polio a programmatic public health emergency in 2012; as of 31 December 2013, only 3 countries (Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan) remained endemic for polio [2, 3]. However, the risk of WPV importation into currently polio-free areas will remain until global polio eradication is achieved.

For the European region, this risk became a reality in 2010 when importation of WPV type 1 (WPV1) of Indian origin resulted in a large-scale outbreak involving countries of Central Asia (Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan) and the Russian Federation (Table 1) [4, 5]. In 2011, the WPV1 outbreak in China posed additional risk of WPV introduction into the region (Table 1). During 2012–2013, WPV1 circulation was detected in the Middle East (Table 1), including Israel, which is a country in the WHO European region, Egypt, West Bank, and Gaza Strip, where the virus has been detected through environmental surveillance in the absence of reported paralytic cases [6–8], and the Syrian Arab Republic (referred to here as “Syria”), where the poliomyelitis outbreak is currently occurring [14, 15]. The WPV1 isolates from 2012–2013 in the Middle East are of Pakistani origin and closely related to each other. The circumstances of WPV1 introduction into the Middle East are unclear, but the virus has been present there at least since late 2012 [13].The outbreak in Syria, which is unfolding against the background of the ongoing conflict and mass population displacement, poses particular risk of further spread [14,15].In the WHO European region, Turkey currently hosts more than 600 000 Syrian refugees, and more distant member states are also receiving substantial numbers of refugees [16, 17].

Table 1.

Wild Poliovirus Importations Into the European Region and Bordering Areas of Other Regions, 2010–2013

| Importations into the European region | |

| 2010 | Large-scale multicountry outbreak with 480 laboratory-confirmed cases caused by introduction of WPV1 of Indian origin. The outbreak began in Tajikistan (461 cases) and spread to Russian Federation (15 cases), Turkmenistan (3 cases), and Kazakhstan (1 case) [4, 5]. In addition to young children, older children and young adults were also affected. Although the outbreak in Tajikistan was detected late because of surveillance failure (delay of specimen shipment to laboratory), multiple rounds of SIAs implemented rapidly after the outbreak was recognized led to successful interruption of WPV1 transmission in the region within <6 mo of detection. |

| 2013 | Widespread circulation of WPV1 of Pakistani origin in Israel in the absence of paralytic polio cases. WPV1 was first identified in May in sewage samples from southern Israel tested through routine environmental surveillance. Subsequent testing revealed presence of the virus in environmental samples from other parts of Israel as well, with the earliest positive samples collected in February. In response to the introduction, the Israel MOH initiated SIAs with bOPV initially in the south, then nationwide (beginning August 18). As of 26 December 2013, nationwide coverage was 65.8%. As of October 2013, the virus transmission was still ongoing. To accelerate interruption of WPV1 transmission, in November 2013, the decision to add bOPV into the routine immunization schedule was taken by the Israel MOH [6–10]. |

| Importations into the bordering areas of other WHO regions | |

| 2011 | Importation into the Western Pacific Region, certified polio-free in 2000 [11], of WPV1 of Pakistani origin caused an outbreak with 21 confirmed cases in the Xinjiang province of China [12], which borders Central Asian countries of the European region (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan). Despite the risk of the virus spread from China, no polio cases related to this outbreak were reported in the European region. |

| 2012 | Importation of WPV1 of Pakistani origin into Egypt in 2012 [13]. WPV1 of Pakistani origin was detected in 2 environmental samples from Cairo in December 2012. To interrupt virus transmission, subnational SIAs were conducted in February 2013–March 2013, followed by a nationwide SIA in April. The environmental samples in Egypt have remained negative since the SIAs. |

| 2013 | Importation of WPV1 into Gaza Strip and West Bank of the WHO Eastern Mediterranean region. During 2013, WPV1 of Pakistani origin was detected in sewage samples collected in West Bank and Gaza Strip. No cases of paralytic polio have been reported. As of November 2013, the SIA is underway in response to these detections and the outbreak in Syria [7, 8, 14]. |

| 2013 | In the fall of 2013, at least 17 laboratory-confirmed poliomyelitis cases due to WPV1 were identified in Syria, a member state of the WHO Eastern Mediterranean region. The virus is of Pakistani origin and is related to viruses identified during 2012–2013 in environmental samples in Egypt, Israel, Gaza Strip, and West Bank [8]. Most cases are among children aged <2 y. As of late November, transmission was ongoing and large-scale vaccination campaigns had been initiated in Syria and surrounding countries [14, 15]. |

Abbreviations: bOPV, bivalent oral polio vaccine; MOH, Ministry of Health; SIA, supplementary immunization activity; WHO, World Health Organization; WPV1, wild poliovirus type 1.

Here, we review the experience of the European region in maintaining its polio-free status over the past decade, with a focus on challenges since 2010. Also, we assess the status of critical activity areas and discuss current threats and preventive measures.

METHODS

We reviewed data on the following 3 major determinants of the risk of poliovirus transmission: population immunity, surveillance performance, and outbreak preparedness. The results of assessments of risk of poliovirus spread following introduction, polio immunization policies and coverage, national preparedness plans, and activities implemented in countries in response to recent WPV introductions were also reviewed.

The RCC is an independent advisory body to the WHO regional office for Europe, which reviews the performance of national polio programs and determines if poliovirus circulation in the region remains interrupted. The RCC certified the European region as polio free in 2002 and continues to meet annually to review and assess countries’ risk of poliovirus outbreaks in the event of virus importation. To help maintain polio situation awareness and preparedness, the RCC recommended that each country have a functioning national certification committee (NCC), that is, an independent body that reviews the current country data and submits annual progress reports to the RCC.

We obtained results of annual risk assessments for 2010–2013 from RCC reports [18–22]. The risk assessment methodology includes analysis of the major factors (described above) that potentially influence the risk of poliovirus transmission. The overall risk level (low, intermediate, or high) of WPV spread if it were introduced is assigned based on the performance of the country in each area [22, 23].

We obtained immunization coverage by country from WHO/UNICEF joint reporting form (JRF) data [24, 25]. We also reviewed annual WHO and UNICEF estimates of national immunization coverage [25, 26]. The information on supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) conducted during 2010–2013 was obtained from annual progress reports submitted by NCCs to RCC. The information on vaccination schedules and vaccines used for routine immunization was obtained from the annual WHO/UNICEF JRF [25].

Poliomyelitis is a notifiable condition through communicable disease surveillance in all member states. Acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance with defined performance criteria is recommended by WHO as the standard method, while enterovirus and environmental surveillance are considered acceptable supplementary means of surveillance for polioviruses. We obtained data on reported polio cases and WPV isolations, as well as AFP surveillance from routine country reports submitted to the WHO regional office. Information on the status of supplementary surveillance systems was obtained from annual progress reports submitted to RCC. We also reviewed the national preparedness plans for each country and the internal reports of the 3 polio outbreak simulation exercises implemented during 2011–2013.

RESULTS

NCCs

In 2012, 51 of 53 countries had an NCC. However, no meetings were held in 6 countries, and more than 1 meeting occurred in only 20 countries. Two countries (Hungary and Italy) do not currently have an NCC.

Risk Assessments

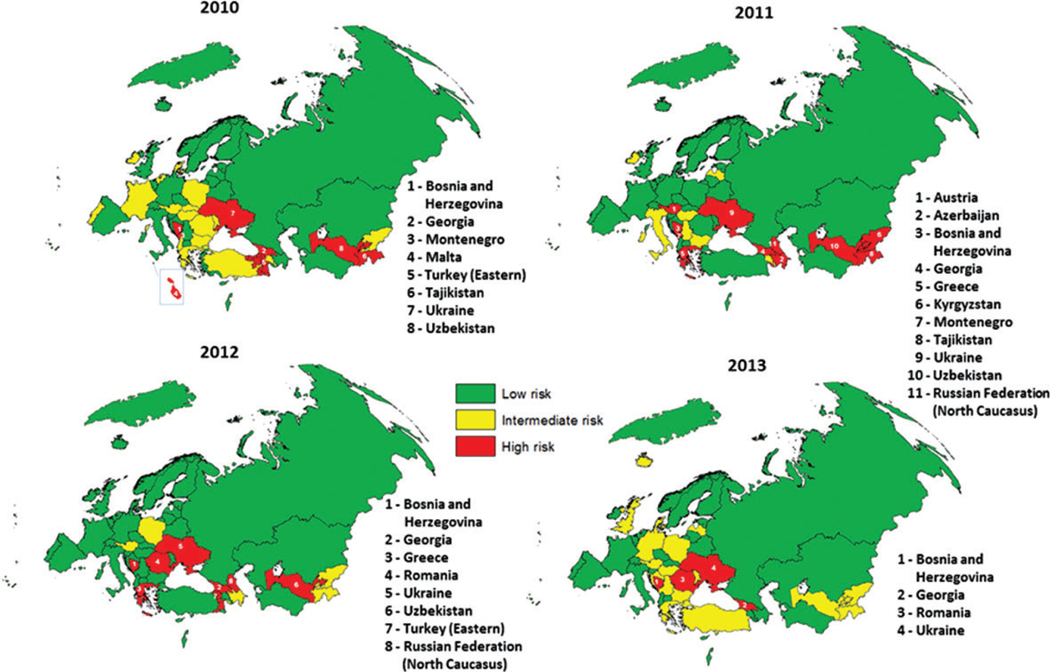

Each year during 2010–2013, risk assessments identified several countries that were at high or intermediate risk of poliovirus transmission following importation (Figure 1), primarily due to suboptimal coverage and/or surveillance. Some countries at overall low risk for poliovirus transmission had subnational areas at a higher risk, for example, North Caucasus in the Russian Federation and the eastern part of Turkey. In 2013, 4 countries (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Romania, and Ukraine) were considered to be at high risk and 18 countries (Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Malta, Poland, Republic of Moldova, San Marino, Serbia, Tajikistan, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and Uzbekistan) at intermediate risk.

Figure 1.

Risk of wild poliovirus spread following importation in countries of the European region, 2010–2013. Countries ranked at high risk in a given year are individually listed.

Population Immunity

Routine Immunization

Since 2003, regional coverage with 3 routine doses of polio vaccine (Pol3), either oral polio vaccine (OPV) or inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), has been high (94%–97%). According to national annual reports, most countries achieved ≥95% Pol3 coverage during 2010–2012, but some countries had coverage <90% (Figure 2). In 2012, ≥95% coverage was reported by 37 of 53 countries, 90%–94% by 10 countries, and <90% by 3 countries. The 2012 Pol3 coverage data were not available for 3 countries (Austria, Luxemburg, and Monaco). Reported coverage was <90% in Ukraine (74%), Bosnia and Herzegovina (87%), and Iceland (89%). Azerbaijan reported high (96%) coverage, but the WHO/UNICEF estimate was substantially lower (78%). WHO/UNICEF estimates are somewhat lower but generally concur with high reported coverage for most countries (Figure 2). In 2012, WHO/UNICEF estimated coverage was ≥95% for 39 countries, 90%–94% for 10 countries, and <90% for 4 countries. Of particular concern is the decline of historically high coverage in Ukraine since 2009 to the low of 56%–57% during 2010–2011. A consistent declining trend (from 95% in 2007 to 87% in 2012) was also observed in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In addition, many countries had underperforming districts at the subnational level or lacked subnational coverage data for 2010–2012 (Figure 3). Specific population groups with low coverage, for example, mobile groups with limited access to healthcare; persons who object to immunization on religious, philosophical, or other grounds, also exist in many countries.

Figure 2.

Routine immunization coverage with 3 doses of polio vaccine (Pol3) in countries of the European region, 2003–2012.

Figure 3.

Coverage with three doses of polio vaccine (Pol3) at subnational level, European region, 2010–2012.

In 2012, 12 countries used trivalent OPV (tOPV) exclusively for routine immunization, 34 countries used IPV exclusively, and 7 countries used both. The recommended age for vaccination was between 6 weeks and 3 months for the first polio vaccine dose and between 5 months (Kyrgyzstan; schedule, the birth dose plus 3 doses at 2, 3.5, and 5 months) and 26–28 years (France) for the last dose. In 43 countries the schedule included at least 3 doses before the first birthday; in 3 countries the third dose was given shortly before or after the first birthday; and 7 countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Poland, San Marino, and Sweden) recommended only 2 doses before the first birthday. The total number of recommended doses varied between 3 and 7. Six countries (Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) recommended a birth dose of OPV.

SIAs

Historically, large-scale SIAs, particularly those conducted as part of Operation MECACAR (Mediterranean, Caucasus, and Central Asian Republics), involved a large-scale coordinated immunization effort in adjoining countries of 2 WHO regions —European and Eastern Mediterranean. Synchronized national and subnational immunization days with OPV were observed in 18 countries, reaching more than 60 million children during 1995–2000 [27] in the eastern part of the region [27] and contributing greatly to achievement of polio-free status for the European region. However, mass immunization campaigns were largely discontinued after regional polio-free certification was achieved and were started back up only when the 2010 outbreak occurred. In 2010, SIAs implemented in infected and bordering countries (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, the Russian Federation, and Uzbekistan; Table 2) were instrumental to the rapid interruption of WPV1 circulation and helped prevent reestablishment of transmission (defined as transmission of imported WPV sustained for more than 12 months in a given country) of imported virus in the region. More than 48 million doses of vaccine were administered through SIAs in 2010 in these 6 countries. In Tajikistan, the initial outbreak response was notable for the use of monovalent type 1 OPV (mOPV1) with short (2-week) intervals between rounds. tOPV at 1-month intervals was used in subsequent rounds. In addition, because of the large number of persons aged >5 years in this outbreak, the age range for SIAs was extended to 15 years. High reported coverage (≥95%) with these SIAs was validated via independent monitoring (Table 2) and by a nationwide serosurvey in Tajikistan [4] that demonstrated 98.9% seroprevalence for poliovirus type 1 after the mOPV1 rounds in 2010. During 2011–2013, the affected countries continued to conduct SIAs during follow-up after the outbreak, while Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, and Georgia implemented preventive subnational SIAs to close immunization gaps (Table 2). In 2013, SIAs using bivalent OPV (bOPV) were conducted in Israel among children aged <10 years in response to WPV1 importation (Table 2). To prevent virus spread from Syria where WPV1 outbreak is currently ongoing, a massive coordinated immunization response is underway in Syria and surrounding countries, including Turkey (Table 2) [15].

Table 2.

Polio Supplemental Immunization Activities Conducted in the European Region, 2010–2013

| Country | Dates | SIA Type | Vaccine | Target Groups | No. Targeted | No. Vaccinated | Coverage Reported, % | Coverage, Independent Monitoring, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIAs in 2010 | ||||||||

| Tajikistan | May 4–8 | National | mOPV1 | 0–5 y | 1 133 841 | 1 127 107 | 99.4 | 94.5 |

| May 18–22 | National | mOPV1 | 0–5 y | 1 147 696 | 1 139 883 | 99.3 | 99.5 | |

| June 1–5 | National | mOPV1 | 0–16 y | 2 934 740 | 2 900 646 | 98.8 | 97.5 | |

| June 15–19 | National | mOPV1 | 0–16 y | 2 934 740 | 2 915 319 | 99.3 | 96.4 | |

| Sept. 13–17 | Subnational (34 districts) | mOPV1 | 0–14 y | 1 848 744 | 1 834 358 | 99.2 | N/A | |

| Oct. 4–8 | National | tOPV | 0–14 y | 2 730 212 | 2 718 597 | 99.6 | N/A | |

| Nov. 8–12 | National | tOPV | 0–14 y | 2 790 864 | 2 779 185 | 99.6 | N/A | |

| Uzbekistan | May 17–21 | National | mOPV1 | 0–4 y | 2 850 393 | 2 873 623 | 100.8 | 99.0 |

| June 7–13 | National | mOPV1 | 0–4 y | 2 885 732 | 2 896 466 | 100.4 | 99.3 | |

| July 5–9 | National | mOPV1 | 0–4 y | 2 896 447 | 2 910 685 | 100.5 | 98.0 | |

| July 26–30 | Subnational (7 districts in Surkhandarya Oblast) | mOPV1 | 0–25 y | 425 085 | 394 787 | 92.9 | N/A | |

| Nov. 25–Dec. 1 | National | mOPV1 | 0–14 y | 9 266 279 | 9 283 307 | 100.2 | N/A | |

| Kyrgyzstan | July 19–23 | National | mOPV1 | 0–4 y | 670 165 | 638 326 | 95.2 | 96.7 |

| Aug. 23–27 | National | mOPV1 | 0–4 y | 681 142 | 657 642 | 96.5 | 96.6 | |

| Kazakhstan | Sept. 6–10 | National | tOPV | 0–5 y | 1 675 285 | 1 656 253 | 98.9 | N/A |

| Oct. 12–14 | Subnational (3 districts in the south) | tOPV | 6 mo–14 y | 155 613 | 153 153 | 98.4 | N/A | |

| Nov. 1–10 | Subnational (6 regions) | mOPV1 | 0–15 y | 2 206 067 | 2 143 472 | 97.2 | N/A | |

| Turkmenistan | May 24–28 | Subnational (Ashgabad) | tOPV | 0–5 y | 44 900 | 44 697 | 99.5 | N/A |

| July 12–18 | National | tOPV | 0–5 y | 567 600 | 565 356 | 99.6 | N/A | |

| July 28–Aug. 6 | Subnational (2 provinces bordering Uzbekistan) | tOPV | 0–25 y | 1 038 900 | 1 027 502 | 98.9 | N/A | |

| Aug. 26–Sept. 5 | National | mOPV1 | 0–14 y | 1 488 800 | 1 482 796 | 99.6 | N/A | |

| Sept. 20–29 | National | mOPV1 | 0–14 y | 1 499 200 | 1 493 205 | 99.6 | N/A | |

| Russian Federation | Nov. 1–5 | Subnational (North Caucasus and Southern Federal District) | tOPV | 6 mo-14 y | N/A | >2 200 000 | 99.5 | N/A |

| Nov. 29–Dec. 3 | Subnational (North Caucasus and Southern Federal District) |

tOPV | 6 mo-14 y | N/A | >2 200 000 | 99.5 | N/A | |

| Jan.–Dec. | 42 Federal District, mop-up | tOPV | 1–3 y | N/A | >52 800 | N/A | N/A | |

| Georgia | June | Subnational (Marneuli district) | tOPV | 0–6 y | 10 318 | 10 290 | 99.7 | N/A |

| May–June | National mop-up | tOPV | 0–6 y | 17 349 | 9150 | 52.7 | N/A | |

| Nov. 8–14 | Subnational (Abkhazia) | tOPV | 0–17 y | 37 586 | 36 925 | 98.2 | N/A | |

| Dec. 6–12 | Subnational (Abkhazia) | tOPV | 0–17 y | 37 897 | 37 026 | 97.7 | N/A | |

| Turkey | Sept. 20–26 | Subnational (Sanlıurfa, Agrı, Sırnak) | tOPV | 0–5 y | 379 968 | 317 356 | 83.5 | 80 |

| Oct. 18–24 | Subnational (Sanlıurfa, Agrı, Sırnak) | tOPV | 0–5 y | 379 968 | 335 444 | 88.3 | 85 | |

| SIAs in 2011 | ||||||||

| Tajikistan | April 18–22 | National | tOPV | 0–4 y | 1 000 294 | 993 566 | 99.3 | 96 |

| May 23–27 | National | tOPV | 0–4 y | 1 024 272 | 1 016 078 | 99.2 | 98.1 | |

| Turkmenistan | April 25–30 | National | tOPV | 0–4 y | 604 225 | 598 437 | 99 | 99.4 |

| May 30–June 4 | National | tOPV | 0–4 y | 616 803 | 611 133 | 99.1 | 97.6 | |

| Kyrgyzstan | April 18–23 | National | tOPV | 0–14 y | 1 690 188 | 1 605 311 | 95 | 96.1 |

| May 23–28 | National | tOPV | 0–14 y | 1 583 463 | 1 518 541 | 95.9 | 94.2 | |

| Uzbekistan | April 18–23 | National | tOPV | 0–4 y (1 province, 0–14 y) | 3 058 796 | 3 071 031 | 100.4 | 96.1 |

| May 23–28 | National | tOPV | 0–4 y (1 province, 0–14 y) | 2 987 557 | 2 990 544 | 100.1 | 97 | |

| Kazakhstan | Feb. 21–25 | Subnational | mOPV1 | 0–6 y | 411 653 | 406 922 | 98.9 | N/A |

| May 3–7 | National | tOPV | 7–15 y | 1 710 321 | 1 677 825 | 98.1 | 89.5 | |

| May 16–20 | Subnational | mOPV1 | 0–15 y | 383 920 | 383 318 | 99.8 | N/A | |

| Azerbaijan | April 25–30 | Subnational | tOPV | 0–5 y | 32 033 | 31 164 | 97.3 | N/A |

| May 23–29 | Subnational | tOPV | 0–5 y | 31 928 | 31 392 | 98.3 | N/A | |

| Georgia | May | Subnational (district with <90% coverage) | tOPV | 1–14 y | 32 690 | 25 367 | 77.6 | N/D |

| June | Subnational (district with <90% coverage) | tOPV | 1–14 y | 33 872 | 29 474 | 87 | N/D | |

| Bulgaria | April–May | National | IPV | 13 mo-7 y | Not reported | 39 754 | N/D | N/D |

| Russian Federation | April 4–9 | Subnational | tOPV | 6 mo-15 y | 1 394 121 | 1 389 809 | 99.7 | N/A |

| May 3–7 | Subnational | tOPV | 6 mo-15 y | 1 393 975 | 1 390 176 | 99.7 | N/A | |

| SIAs in 2012 | ||||||||

| Russian Federation | 23–27 April | Subnational (North Caucasus Federal District and 62 selected districts) |

tOPV | 1–3 y | Not reported | >88 000 | 97.0 | N/A |

| 29–31 May | Subnational (North Caucasus Federal District and 62 selected districts) |

tOPV | 1–3 y | Not reported | 227 000 | 99.0 | N/A | |

| Uzbekistan | 23–28 April | Subnational | tOPV | 0–5 y | 1 942 898 | 1 939 347 | 99.8 | N/A |

| 21–26 May | Subnational | tOPV | 0–5 y | 1 962 903 | 1 960 230 | 99.9 | N/A | |

| SIAs in 2013 | ||||||||

| Kyrgyzstan | 23–26 April | Subnational | tOPV | 0–4 y | 178 577 | 173 733 | 97.3 | N/A |

| 28–31 May | Subnational | tOPV | 0–4 y | 181 297 | 176 652 | 97.4 | N/A | |

| Uzbekistan | 22–27 April | Subnational | tOPV | 0–5 y | 1 937 809 | 1 937 710 | 100.0 | N/A |

| May | Subnational | tOPV | 0–5 y | 1 953 774 | 1 952 695 | 99.9 | N/A | |

| Israela | Aug.-Oct. | National | bOPV | 2 mo-9 y | 1 383 135 | 910229 | 65.8 | N/A |

| Turkeyb | From Nov. | Subnational | tOPV | 0–5 y | 1 060 000 | N/D | N/D | N/A |

| Adana, Gaziantep, Hatay, Kilis, Mardin, Sanliurfa, and Sirnak | All children | |||||||

| Adiyaman, Malatya KahramanmaraŞ, Osmaniye, and high-risk areas of other provinces | Syrian children; other children with potential contact with them |

Abbreviations: MOPV1, monovalent type 1 oral polio vaccine; N/A, not applicable; SIA, supplementary immunization activity; tOPV, trivalent oral polio vaccine.

Data reported by the Israel Ministry of Health as of 26 December 2013 [9].

As of late November, the SIA in Turkey is underway; coverage data have not been reported yet.

Surveillance

At least 1 of the 3 specialized surveillance systems (AFP, enterovirus, and environmental surveillance) was in place in 50 countries in 2012 (Luxembourg, Monaco, and San Marino do not have specialized surveillance systems for polio). Sixteen countries conducted all 3 types of specialized surveillance, 20 countries conducted 2 types, and 14 countries conducted 1 type only.

AFP Surveillance

As of 2013, AFP surveillance, established in the mid-1990s, is in place in 41 countries (Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Monaco, the Netherlands, San Marino, Sweden, and the United Kingdom do not conduct AFP surveillance. Germany discontinued AFP surveillance after 2010, and Ireland after 2011). Since certification, the region has been meeting most of the principal performance indicators for AFP surveillance (nonpolio AFP rate, stool collection rate, timeliness of case notification and investigation; Table 3). However, completeness and, particularly, timeliness of reporting by countries have been on the decline since 2008.

Table 3.

Performance of the Acute Flaccid Paralysis Surveillance, European Region, 2003–2013

| Variable | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013a | Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries reporting AFP surveillance data, no. | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 43 | 42 | 41 | 41 | N/A |

| Reported AFP cases, all ages, no. | 1544 | 1543 | 1504 | 1504 | 1458 | 1372 | 1379 | 2265 | 1570 | 1562 | 1439 | N/A |

| Reported AFP cases aged <15 y, no. | 1528 | 1523 | 1491 | 1491 | 1451 | 1360 | 1366 | 2107 | 1552 | 1537 | 1402 | N/A |

| Confirmed polio cases, no. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 480 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Polio-compatible cases, no. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 58 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nonpolio AFP rate | 1.12 | 1.14 | 1.13 | 1.15 | 1.12 | 1.05 | 1.06 | 1.63 | 1.20 | 1.18 | 1.07 | >1.0 |

| AFP surveillance indexb | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.93 | >0.8 | |

| AFP cases with 2 adequate stool specimens, %c | 83 | 81 | 82 | 91 | 82 | 82 | 84 | 86 | 87 | 89 | >80% | |

| AFP cases notified within 7 d of onset, % | 76 | 75 | 74 | 76 | 76 | 76 | 76 | 83 | 79 | 81 | 79 | >80% |

| AFP cases with <48 h between notification and case investigation, % | 87 | 87 | 86 | 86 | 87 | 87 | 89 | 89 | 91 | 92 | 90 | >80% |

| Completeness of zero reporting, %d | N/D | N/D | 88 | 89 | 90 | 79 | 78 | 75 | 78 | 81 | 73 | >80% |

| Timeliness of zero reporting, %e | N/D | N/D | 79 | 80 | 82 | 65 | 58 | 55 | 57 | 63 | 62 | >80% |

Abbreviations: AFP, acute flaccid paralysis; N/A, not applicable; N/D, no data available.

2013 data are preliminary, as reported by week 47 of 2013; nonpolio AFP rates and surveillance index for 2013 are annualized.

Nonpolio AFP rate multiplied by the proportion of cases with stool specimen.

Percent of AFP cases with 2 stool specimens collected 24–48 h apart within 14 d of onset.

Percent of reports to World Health Organization received from the number of expected reports.

Percent of reports to World Health Organization received on time.

During 2010–2013, AFP surveillance quality varied widely across countries. The best performance was usually observed in the eastern part of the region, while AFP surveillance in western European countries generally remained substandard (Figure 4). In 2012, 17 countries had met or exceeded the 1.0/100 000 target for nonpolio AFP rate; adequate stool specimens were collected from ≥80% of cases in 20 countries. However, many countries, even if performing well at the national level, had underperforming or “silent” regions (Figure 4), suggesting the existence of gaps in AFP surveillance.

Figure 4.

(A) Annual acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance index at national level and (B) average nonpolio AFP rate per 100 000 population at subnational level, European region, 2010–2012. *2013 index is annualized based on the data reported to WHO as of week 47 of 2013. AFP surveillance index is calculated by multiplying the nonpolio AFP rate per 100 000 population by the proportion of cases with stool specimens.

In the European region, testing of specimens from AFP cases for polioviruses is conducted through the regional network of laboratories (LabNet). In 2012, this network comprised 48 laboratories: 32 national, 9 subnational, and 7 regional reference laboratories (RRLs). The network laboratories undergo annual external quality assurance and accreditation by WHO. The countries without accredited national laboratories submit specimens to other national laboratories or directly to respective RRLs. During 2010–2012, all but 1 national laboratory (Uzbekistan) received accreditation.

During 2010–2012, LabNet consistently met the performance criteria for timeliness of laboratory investigation. However, in some cases, difficulties with specimen transport, particularly across international borders, created barriers to laboratory testing. In 2010, there was a substantial delay in the shipment of specimens from Tajikistan to the RRL. Specimens from AFP cases from January 2010–March 2010 were not shipped to the RRL in Moscow until mid-April. WPV1 was confirmed by the RRL on April 18. However, by the time WPV1 was first confirmed, 140 AFP cases had occurred and WPV1 was subsequently confirmed in 112 of them. Also in 2010, the national laboratory in Uzbekistan lost certification because of the inability to send specimens to RRL; this delay was the result of national restrictions imposed on international transport of biological material.

To enhance laboratory-based polio surveillance in the region, LabNet introduced the laboratory data management system (LDMS) for web-based reporting in 2010. LDMS is linked with AFP surveillance data; this allows for laboratory results to be merged with case-based data. In addition, LDMS allows for better documentation of geographic location and strengthens data management and information exchange. As of 2013, all network laboratories were using LDMS for reporting to the WHO regional office.

Enterovirus and Environmental Surveillance

With substandard AFP surveillance in many countries, supplementary surveillance is increasingly important in the region. In 2012, enterovirus surveillance, based on reporting enteroviruses detected from human specimens, was in place in 39 countries, including 6 countries (Denmark, Germany, Iceland [initiated in 2012], Ireland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom) that relied exclusively on enterovirus surveillance. During 2010–2012, 310 066 specimens were tested for enteroviruses in reporting laboratories (87 982 in 2010, 106 010 in 2011, and 116 074 in 2012). In 2012, the reported number of human specimens tested for enteroviruses was <100 in 9 countries, 100–999 in 14 countries, 1000–9999 in 14 countries, and ≥10 000 in 2 countries. France, Russian Federation, Ukraine, and the Netherlands reported the highest number of tests.

In 2012, environmental surveillance based on testing sewage samples for enteroviruses was conducted in 22 countries. All countries also had at least 1 other surveillance system for polioviruses. During 2010–2012, reporting laboratories tested 54 410 environmental specimens (17 342 in 2010; 18 965 in 2011; 18 103 in 2012). In 2012, <100 environmental specimens were tested in 9 countries, 100–999 specimens in 11 countries, 1000–9999 specimens in 1 country, and ≥10 000 specimens in 1 country. Russian Federation, Ukraine, and Belarus reported the highest number of specimens tested.

The limitations of supplementary surveillance include aggregate reporting without geographical or clinical details, testing commonly conducted in nonnetwork laboratories that might not always undergo adequate quality assurance procedures, variety of laboratory testing methods used, and lack of standardized performance criteria and guidelines, particularly for enterovirus surveillance. To address these limitations, the WHO European Regional Office, together with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, recently developed guidelines for enterovirus surveillance in the European region. Earlier, WHO had developed the guidelines for environmental surveillance [28]. In addition, beginning in 2013, countries were requested to report enterovirus detections by specimen type through LDMS, which should improve the quality of data used to assess representativeness of surveillance.

During 2010–2012, member states reported between 109 144 and 129 142 specimens tested annually through AFP, enterovirus, and environmental surveillance and identified 561 WPV1 (all in 2010), 3757 Sabin-like polioviruses (1408 in 2010, 1210 in 2011, 1117 in 2012), 53 vaccine-derived polioviruses (VDPV; 30 in 2010, 15 in 2011, and 8 in 2012), and 26 602 nonpolio enteroviruses (7289 in 2010, 10 474 in 2011, and 8839 in 2012).

Outbreak Preparedness

All countries should have preparedness plans in place in order to respond to WPV introduction, but only 44 countries reported having national plans in place during 2010–2013. The available plans were often inadequate, missing essential components (eg, the plans for vaccine supply in case of WPV introduction).

To test polio outbreak preparedness, 3 simulation exercises were implemented during 2011–2013 [29]. The exercises allowed identification of deficiencies concerning outbreak response immunization, crisis communications, use of international health regulation mechanisms [30], and resource consideration. These exercises revealed the need to strengthen WHO guidance, including updating the regional polio guidelines [31].

Communication remains an important challenge in many countries, and additional training is needed to improve the communication skills of public health officials. To aid countries in addressing communication challenges, the WHO regional office developed a series of publications on vaccine communication and advocacy (available at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/vaccines-and-immunization/publications) and provided technical assistance to WPV-affected countries. The annual European Immunization Week activities have become an important platform for maintaining the countries’ focus on immunization issues, including polio.

DISCUSSION

In 2013, prolonged WPV1 circulation in Israel and the threat of importation from Syria into countries with susceptible, nonimmunized populations represented the greatest challenges to maintaining the polio-free status of the European region. In addition, there is a continued risk of introduction from endemic and other polio-affected countries. Ensuring adequate response to these challenges is the top regional priority.

The situation in Israel is unique, and its implications are not yet fully understood. No other country had previously documented a widespread and prolonged silent circulation of imported WPV in OPV-naive populations with high IPV vaccination coverage. For Israel and the region to maintain polio-free status, it is crucial that the WPV1 circulation be interrupted as soon as possible. To accelerate interruption of circulation and prevent reestablished transmission of WPV1 in Israel, continued immunization response is needed. Recently, national authorities added bOPV to the routine immunization schedule [10].

Because of the difficulties facing outbreak control efforts within Syria, high-quality SIAs in the surrounding countries, including Turkey, will be essential in preventing further virus spread. To mitigate the risk of WPV introduction by incoming refugees, member states should ensure that refugees from polio-infected countries who do not have documentation of receipt of polio vaccine prior to arrival to a host country are vaccinated as soon as possible after arrival. Also, to minimize local susceptibility and reduce the risk of imported virus spread, countries should review their immunization coverage and close immunity gaps in any identified high-risk geographic area or underimmunized population groups.

As an important lesson to be learned, the outbreak of 2010 demonstrated the value of investing in prevention and early detection. In 2009, preventive SIAs were considered but not implemented in Tajikistan because of the lack of necessary funds (approximately $1 000 000). The WHO Regional Office estimated the costs of the response to the outbreak, which began in early 2010, to be more than $11 000 000, not including countries’ contributions.

Until polio is eradicated globally, importations cannot necessarily be prevented, but a high level of population immunity can curtail the imported virus spread. Strengthening routine immunization systems, the backbone for all vaccine-preventable disease eradication, elimination and control programs, and closure of existing immunity gaps through SIAs in all geographic areas and populations, including high-risk and mobile groups, are the keys to creating the “firewall of immunity” against polioviruses. It is concerning that SIAs to close immunity gaps have not yet been implemented in most countries ranked at high risk in 2013. Conducting catch-up SIAs is particularly important for Ukraine, where the number of susceptible individuals continues to increase due to sustained low coverage since 2009. To ensure protection against all 3 poliovirus types and help prevent emergence of circulating VDPVs, the polio eradication endgame strategy [32] includes the requirement that all countries, including countries of the European region currently using only OPV, introduce at least 1 IPV dose in their routine immunization schedules by 2015.

The importance of early detection of imported WPV for preventing further virus spread cannot be overestimated. In 2010, surveillance failure in Tajikistan resulted in late recognition of the outbreak and likely contributed to its large scale. Investment in strengthening surveillance and laboratory systems can serve as another “line of defense” for sustaining polio-free status by allowing early detection of importations. To avoid delays in virus detection and response implementation, the logistical and regulatory issues regarding specimen transport across borders should be resolved as soon as possible.

Quality of AFP surveillance should be maintained and further improved. However, for high-income countries with no or chronically underperforming AFP surveillance systems, well-performing supplementary surveillance remains an acceptable option. Despite the limitations of supplementary surveillance, its utility for identification of poliovirus introductions into the European region has been demonstrated over the years by consistent isolation of Sabin-like viruses, VDPVs, and, occasionally, imported WPV (eg, WPV1 originating from Chad was detected in a single environmental specimen in Switzerland in 2007 [33]), including recent importation into Israel. Supplementary surveillance will benefit from further regional guidance and standardization of procedures. Clinician awareness needs to be raised in many countries that have been polio free for decades and where physicians might be unfamiliar with the clinical presentations of polio.

The outbreak in 2010 demonstrates the value of risk assessments in general and provides a good validation for the assigned risk levels. Tajikistan, which was a high-risk country in the 2009 risk assessment, had widespread transmission, while polio-infected low-risk countries (Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan) had very limited or no secondary spread. The Russian Federation, rated as being at low overall risk, had multiple separate introductions, but relatively prolonged secondary spread was only observed in the North Caucasus subregion, which was rated as being at high risk [23, 34]. The risk mitigation activities in the region should focus on high- and intermediate-risk countries. To test and increase preparedness for polio outbreaks, simulation exercises should be implemented by other high- or intermediate-risk countries as well. Countries with large numbers of incoming migrants and refugees from polio-infected countries would particularly benefit from such exercises.

To ensure countries are prepared for rapid and adequate response to WPV importations, existing national plans should include solid strategies for addressing vaccine choice and supply issues. Some IPV-using countries in the region envisage use of IPV for outbreak response in their national plans. However, this approach might have to be reconsidered once the implications of the current widespread WPV1 circulation in Israel are fully understood. However, OPV formulations (particularly mOPV and bOPV), which are the WHO-recommended vaccines for response, are not licensed in most European countries. This is a substantial barrier to their use in case of WPV introduction that needs to be addressed promptly.

Maintenance of the region’s polio-free status by implementing activities to prevent, promptly detect, and rapidly respond to WPV importations requires continued support from all countries. WHO efforts to ensure continued support for polio eradication resulted in the resolution adopted by the Regional Committee for Europe, which urged member states to reinforce their commitment and financial support in order to sustain polio-free status [35].

The success of achieving polio eradication has, for the most part, inspired the establishment of regional elimination goals for measles and rubella [35]. The regional measles and rubella elimination program has benefited from the legacy of polio eradication efforts in the European region, particularly with regard to strategies for achieving and documenting progress toward elimination [36].

In conclusion, despite numerous challenges, the European region has successfully maintained its polio-free status for more than a decade. However, staying polio free requires coordinated efforts, sustained political commitment, and financial support from all member states.

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr Steve Wassilak, Dr George Oblapenko, Ajay Goel, Dr Galina Lipskaya, Dr Shahin Huseinov, and representatives of the National Immunization Programs and National and Regional Poliomyelitis Laboratories for their contributions.

Disclaimers.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and co-authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Some of the co-authors are staff members of the WHO. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policies, or views of the WHO.

Financial support.

The manuscript was written by employees of the WHO and CDC as part of their duties. No additional funding was provided.

Supplement sponsorship.

This article is part of a supplement entitled “The Final Phase of Polio Eradication and Endgame Strategies for the Post-Eradication Era,” which was sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Certification of Poliomyelitis Eradication. In: Fifteenth Meeting of the European Regional Certification Commission, Copenhagen, 19–21 June 2002. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization, 2005:1–128. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Assembly Resolution. Completion of polio eradication programmatic emergency for global public health. http://www.polioeradication.org/Resourcelibrary/Declarationsandresolutions.aspx#sthash.E0iWXsVG.dpuf. Accessed 9 December 2013.

- 3.Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Polio this week—As of 31 December 2013. http://www.polioeradication.org/Dataandmonitoring/Poliothisweek.aspx. Accessed 3 January 2014.

- 4.Khetsuriani N, Pallansch M, Jabirov S, et al. Population immunity topolioviruses in the context of a large-scale wild poliovirus type 1 outbreak in Tajikistan, 2010. Vaccine 2011; 31:4911–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreaks following wild poliovirus importations — Europe, Asia and Africa, January 2009– September 2010. MMWR Weekly 2010; 59:1393–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anis E, Kopel E, Singer SR, et al. Insidious reintroduction of wild poliovirus into Israel, 2013. Eurosurveillance 2013; 18:2–6. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20586. Accessed 9 December 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Poliovirus detected from environmental samples in Israel and West Bank and Gaza Strip. Disease outbreak news, 20 September 2013. http://www.who.int/csr/don/2013_09_20_polio/en/index.html. Accessed 9 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Polio in the Syrian Arab Republic—update. Disease outbreak news, 11 November 2013. http://www.who.int/csr/don/2013_11_11polio/en/index.html. Accessed 9 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Israel Ministry of Health. Supplemental polio vaccination campaign. National polio vaccine coverage. http://www.health.gov.il/Subjects/vaccines/two_drops/Pages/VaccinationCoverage.aspx. Accessed 3 January 2014.

- 10.Tulchinsky TH, Ramlawi A, Abdeen Z, Grotto I, Flahault A. Polio lessons 2013: Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza. Lancet 2013; 382:1611–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public health dispatch: certification of poliomyelitis eradication—Western Pacific Region, October 2000. MMWR Weekly 2001; 50:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo HM, Zhang Y, Wang XQ, et al. Identification and control of a poliomyelitis outbreak in Xinjiang, China. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:1981–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Importation of wild poliovirus detected in environmental (sewage) samples in Egypt. http://www.emro.who.int/polio/polio-news/new-polio-virus-egypt.htm. Accessed 9 December 2013.

- 14.World Health Organization. Polio in the Syrian Arab Republic—update. Disease outbreak news, 26 November 2013. http://www.who.int/csr/don/2013_11_26polio/en/index.html. Accessed 9 December 2013.

- 15.World Health Organization. Over 23 million children to be vaccinated in mass polio immunization campaign across Middle East. http://www.emro.who.int/media/news/massive-polio-vaccination-campaign-middle-east.html. Accessed 9 December 2013.

- 16.UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Humanitarian Bulletin. Syrian Arab Republic; 2013; 39:1–17. http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Syria%20Humanitarian%20Bulletin%20No%2039.pdf. Accessed 18 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Asylum claims in industrialized countries. Latest monthly data. http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49c3646c4d6.html. Accessed 18 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Report of the 23rd Meeting of the European Regional Certification Commission for Poliomyelitis Eradication. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2010. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/poliomyelitis/publications/2010/report-of-the-23rd-meeting-of-the-european-regional-certification-commission-for-poliomyelitis-eradication. Accessed 9 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Report of the 24th Meeting of the European Regional Certification Commission for Poliomyelitis Eradication. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2011. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/poliomyelitis/publications/2011/report-of-the-24th-meeting-of-the-european-regionalcertification-commission-for-poliomyelitis-eradication. Accessed 9 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. Report of the 25th Meeting of the European Regional Certification Commission for Poliomyelitis Eradication. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2011. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/poliomyelitis/publications/2012/report-of-the-25th-meeting-of-the-european-regionalcertification-commission-for-poliomyelitis-eradication. Accessed 9 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Report of the 26th Meeting of the European Regional Certification Commission for Poliomyelitis Eradication. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2012. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/poliomyelitis/publications/2013/report-of-the-26th-meeting-of-the-european-regionalcertification-commission-for-poliomyelitis-eradication. Accessed 9 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. Report of the 27th Meeting of the European Regional Certification Commission for Poliomyelitis Eradication. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2013. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/poliomyelitis/publications/2013/report-of-the-27th-meeting-of-the-european-regionalcertification-commission-for-poliomyelitis-eradication. Accessed 9 December 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowther SA, Roesel S, O’Connor P, et al. World health organization regional assessments of the risks of poliovirus outbreaks. Risk Analysis 2013; 33:664–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. WHO/UNICEF Joint Reporting Process.http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/routine/reporting/reporting/en/. Accessed 9 December 2013.

- 25.World Health Organization. Immunization, vaccines and biologicals—data, statistics and graphics by subject. http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/subject/en/index.html. Accessed 9 December 2013.

- 26.Burton A, Monasch R, Lautenbach B, et al. WHO and UNICEF estimates of national infant immunization coverage: methods and processes. Bull World Health Organ 2009; 87:535–41. http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/87/7/08-053819/en/. Accessed 9 December 2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. Operation MECACAR: eradicating polio. Final report, 1995–2000. WHO, 2001. http://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/12050. Accessed 9 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. Guidelines for environmental surveillance of poliovirus circulation. WHO, 2003. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/67854/1/WHO_V-B_03.03_eng.pdf. Accessed 9 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moulsdale HJ, Khetsuriani N, Deshevoi S, Butler R, Simpson J, Salisbury D. Simulation Exercises to Strengthen Polio Outbreak Preparedness: Experience of the WHO European Region. J of Infect Dis 2014; 210:S208–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization. International Health Regulations (2005),second edition. WHO, 2008. http://www.who.int/ihr/publications/9789241596664/en/index.html. Accessed 9 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. Guidelines on responding to the detectionof wild poliovirus in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2007. http://www.euro.who.int/en/healthtopics/communicable-diseases/poliomyelitis/publications/pre-2009/guidelines-on-responding-to-the-detection-of-wild-poliovirus-in-thewho-european-region. Accessed 9 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Polio eradication and endgame strategic plan 2013–2018. http://www.polioeradication.org/Resourcelibrary/Strategyandwork.aspx. Accessed 9 December 2013.

- 33.World Health Organization. Report of the 21st Meeting of the European Regional Certification Commission for Poliomyelitis Eradication. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2008. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/poliomyelitis/publications/pre-2009/report-of-the-21st-meeting-of-the-european-regionalcertification-commission-for-poliomyelitis-eradication. Accessed 9 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization. Report of the 22nd Meeting of the European Regional Certification Commission for Poliomyelitis Eradication. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2009. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/poliomyelitis/publications/2009/report-of-the-22nd-meeting-of-the-europeanregional-certification-commission-for-poliomyelitis-eradication. Accessed 9 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Regional Committee for Europe resolution EUR/RC60/R12 on renewed commitment to elimination of measles and rubella and prevention of congenital rubella syndrome by 2015 and sustained support for polio-free status in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2010. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/122236/RC60_eRes12.pdf. Accessed 9 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. Eliminating measles and rubella: framework for the verification process in the WHO European Region. WHO, 2012. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/measles-and-rubella/publications/2012/eliminatingmeasles-and-rubella-framework-for-the-verification-process-in-thewho-european-region. Accessed 9 December 2013. [Google Scholar]