Abstract

Background

Pain may increase the risk for sarcopenia, but existing literature is only from high-income countries, while the mediators of this association are largely unknown. Thus, we aimed to investigate the association between pain and sarcopenia using nationally representative samples of older adults from 6 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), and to identify potential mediators.

Methods

Cross-sectional data from the WHO Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE) were analyzed. Sarcopenia was defined as having low skeletal muscle mass and weak handgrip strength, while the presence and severity of pain in the last 30 days were self-reported. Multivariable logistic regression and mediation analyses were performed. The control variables included age, sex, education, wealth, and chronic conditions, while affect, sleep/energy, disability, social participation, sedentary behavior, and mobility were considered potential mediators.

Results

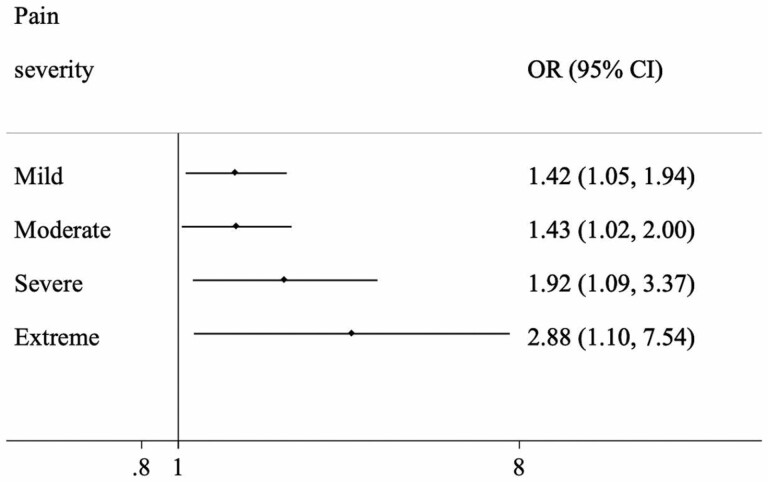

Data on 14,585 adults aged ≥65 years were analyzed (mean [SD] age 72.6 [11.5] years; 55.0% females). Compared to no pain, mild, moderate, severe, and extreme pain were associated with 1.42 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.05–1.94), 1.43 (95%CI = 1.02–2.00), 1.92 (95%CI = 1.09–3.37), and 2.88 (95%CI = 1.10–7.54) times higher odds for sarcopenia, respectively. Disability (mediated percentage 18.0%), sedentary behavior (12.9%), and low mobility (56.1%) were significant mediators in the association between increasing levels of pain and sarcopenia.

Conclusions

Higher levels of pain were associated with higher odds for sarcopenia among adults aged ≥65 years in 6 LMICs. Disability, sedentary behavior, and mobility problems were identified as potential mediators. Targeting these factors in people with pain may decrease the future risk of sarcopenia onset, pending future longitudinal research.

Keywords: Disability, Low- and middle-income countries, Older adults, Pain, Sarcopenia

Sarcopenia is often defined as a progressive loss of muscle mass and function and is one of the most prominent physiological changes associated with aging (1). Indeed, between the ages of 40 to 80 years, total muscle mass reduces by 30%–50% (2). In a recent review of 58,404 individuals, it was reported that the global prevalence of sarcopenia was 10% (3), while a high prevalence of sarcopenia (approximately 16%) has been reported in older adults from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (4).

The high prevalence of sarcopenia is of concern as sarcopenia has been found to be associated with multiple detrimental health outcomes. For example, a recent umbrella review identified that sarcopenia is associated with a higher risk for premature mortality, disability, and falls, with a high level of evidence (5). Moreover, health care expenditure in relation to sarcopenia has also been reported to be high. For instance, annual direct medical costs attributable to sarcopenia were estimated to be approximately $18.5 billion in the United States in 2000, representing 1.5% of total direct health care costs (6).

Given that sarcopenia is an age-related condition, it is highly likely that it would increasingly cause a substantial burden at the individual and societal level in the future due to rapid population aging. In particular, over the next 3 decades, the global number of older people is projected to more than double, reaching over 1.5 billion in 2050. All regions will see an increase in the size of their older population between 2019 and 2050. However, the fastest increase in the older population between 2019 and 2050 is projected to happen in LMICs (+225%), rising from 37 million in 2019 to 120 million people aged 65 years or over in 2050 (7). Thus, it is of utmost importance to identify risk factors for sarcopenia, which is a reversible condition, to aid in the establishment of targeted interventions to prevent this condition, especially in the context of LMICs.

While there is a large body of literature that has identified risk factors for sarcopenia (eg, poor diet, low physical activity) (8–12), one understudied but potentially important risk factor is pain. Pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with actual or potential tissue damage (13). It may be hypothesized that pain potentially increases the risk for sarcopenia via factors such as immobility, sedentary behavior, depression, sleep problems, social isolation, and malnutrition (14,15). However, research is needed to identify whether such variables mediate the potential pain–sarcopenia relationship. In a recent systematic review and meta-analyses including 14 observational studies, it was observed that pain was independently associated with a higher risk of sarcopenia than no pain (odds ratio [OR] 1.35; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.17–1.56; p = .025; I2 = 51.1%) (16). However, all included studies were carried out in high-income countries (HICs). This is a major limitation as results from HICs may not be generalizable to LMICs, since a high prevalence of pain has been reported from LMICs (17), possibly due to lack of adequate treatment for pain or the conditions that cause pain (18). Importantly, owing to a suboptimal management of pain, adverse pain outcomes such as sarcopenia may be more common. Moreover, LMICs differ from HICs in terms of occupational and environmental factors (eg, safety), which have the potential to increase the risk for chronic pain or impede recovery from it (eg, manual labor compounded with a lack of safety regulations). Furthermore, there is a dearth of information on the potential mediators in the association between pain and sarcopenia.

Given this background, the aim of this study was to investigate the association between pain and sarcopenia in 14,585 adults aged ≥65 years from 6 LMICs (China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia, and South Africa). A further aim was to quantify the degree to which affect, sleep/energy, disability, social participation, sedentary behavior, and mobility mediate the association between pain and sarcopenia. We hypothesized that pain will be associated with higher odds for sarcopenia in LMICs, and that this association will be partly mediated by affect, sleep/energy, disability, social participation, sedentary behavior, and mobility.

Method

Data from the Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE) were analyzed. This survey was undertaken in China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia, and South Africa between 2007 and 2010. Based on the World Bank classification at the time of the survey, Ghana was the only low-income country, and China and India were lower-middle-income countries, although China became an upper-middle-income country in 2010. The remaining countries were upper-middle-income countries. Details of the survey methodology have been published elsewhere (19). Briefly, in order to obtain nationally representative samples, a multistage clustered sampling design method was used. The sample consisted of adults aged ≥18 years with oversampling of those aged ≥50 years. Trained interviewers conducted face-to-face interviews using a standard questionnaire. Standard translation procedures were undertaken to ensure comparability between countries. The survey response rates were: China 93%; Ghana 81%; India 68%; Mexico 53%; Russia 83%; and South Africa 75%. Sampling weights were constructed to adjust for the population structure as reported by the United Nations Statistical Division. Ethical approval was obtained from the WHO Ethical Review Committee and local ethics research review boards. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Sarcopenia

Following the criteria of the revised European consensus on the definition and diagnosis of sarcopenia (20), sarcopenia was defined as having low skeletal muscle mass (SMM) as reflected by lower skeletal mass index (SMI) and weak handgrip strength. SMM was calculated based on the equation proposed by Lee and colleagues: SMM= 0.244 × weight + 7.8 × height + 6.6 × sex – 0.098 × age + race – 3.3 (where female = 0 and male = 1; race = 0 [White and Hispanic], race = 1.4 [African American] and race = −1.2 [Asian]) (21). SMM was further divided by body mass index based on measured weight and height to create a SMI (22). Low SMM was defined as the lowest quintile of the SMI based on sex-stratified values (23). Country-specific cut-offs were used to determine low SMI, as this indicator is likely to be affected by racial differences in body composition (24). Weak handgrip strength was defined as <27 kg for men and <16 kg for women using the average value of the 2 handgrip measurements of the dominant hand (20).

Pain

Pain was assessed with the question “Overall in the last 30 days, how much of bodily aches or pain did you have?” with answer options “none” (coded 1), “mild” (coded 2), “moderate” (coded 3), “severe” (coded 4), and “extreme” (coded 5) (25,26). This question did not specify the location of pain or the chronicity of pain This variable was utilized both as categorical and continuous in the analyses. Information on back pain was obtained by asking “Have you experienced back pain during the last 30 days?” Those who answered “yes” to this question were categorized as having back pain.

Mediators

The potential mediators (ie, affect, sleep/energy, disability, social participation, sedentary behavior, and mobility) were selected based on previous literature suggesting the possibility that they can be the result of pain, and a cause of sarcopenia (16). Affect, sleep/energy, and mobility were assessed with 2 questions each. Each of these health domains corresponds to those in common health-related quality-of-life outcome measures such as the Short Form-12 (SF-12) (27), the Health Utilities Index Mark 3 (HUI) (28), and the EUROQOL 5D (29). Moreover, the domains have been used as indicators of functional health status in prior studies utilizing a data set with the same survey questions (30–32). The specific questions are included in Supplementary Table S1. Each item was scored on a 5-point scale ranging from “none” to “extreme/cannot do.” For each separate health status, we used factor analysis with polychoric correlations to obtain a factor score which was later converted to scores ranging from 0 to 100 with higher values representing worse health function (33). Disability was assessed with 6 questions on the level of difficulty in conducting standard basic activities of daily living (ADL) in the past 30 days (washing whole body, getting dressed, moving around inside home, eating, getting up from lying down, and using the toilet). Those who answered severe or extreme/cannot do to any of the 6 questions were considered to have a disability (34). Following a protocol from previously published research (34), a social participation scale was created based on 9 questions on the participant’s involvement in community activities in the past 12 months (eg, attended religious services, club, society, union, etc.) with answer options “never (coded = 1),” “once or twice per year (coded = 2),” “once or twice per month (coded = 3),” “once or twice per week (coded = 4),” and “daily (coded = 5).” The answers to these questions were summed and converted to a scale ranging from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating higher levels of social participation. In order to assess sedentary behavior, participants were asked to state the total time they usually spent (expressed in minutes per day) sitting or reclining including at work, at home, getting to and from places, or with friends (eg, sitting at a desk, sitting with friends, traveling in car, bus, train, reading, playing cards, or watching television). This did not include time spent sleeping. The variable on time spent sedentary was used as a continuous variable (hours/day).

Control Variables

The control variables in this study included age, sex, the highest level of education achieved (≤primary, secondary, tertiary), wealth quintiles based on income, and chronic conditions. Information on 7 chronic physical diseases (angina, arthritis, asthma, chronic lung disease, diabetes, edentulism, and stroke) were obtained. The details on the diagnosis of these conditions are provided in Supplementary Table S2. The number of chronic conditions was summed and categorized as 0, 1, and ≥2.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using Stata 14.2 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). The analysis was restricted to survey respondents aged ≥65 years as sarcopenia is an age-related condition (35). The difference in sample characteristics was tested by Chi-squared tests and Student’s t-tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to analyze the association between pain or back pain (exposures) and sarcopenia (outcome). Using the overall sample, the association between pain severity (ie, none, mild, moderate, severe, extreme as a categorical variable) and sarcopenia was assessed. Next, using country-wise samples, the association between pain (as a continuous variable) or back pain and sarcopenia was examined. In order to assess between-country heterogeneity, the Higgins’s I2, which represents the degree of heterogeneity that is not explained by sampling error was calculated. Values of 25%, 50%, and 75% are considered as low, moderate, and high levels of heterogeneity (36). An overall estimate was obtained based on country-wise estimates by meta-analysis with fixed effects.

Finally, mediation analysis was conducted to gain an understanding of the extent to which various factors (ie, affect, sleep/energy, ADL disability, social participation, sedentary behavior, mobility) may explain the association between increasing severity of pain and sarcopenia in the overall sample. We used the khb (Karlson Holm Breen) command in Stata (37) for the mediation analysis. This method can be applied in logistic regression models and decomposes the total effect (ie, unadjusted for the mediator) of a variable into direct (ie, effect of pain on sarcopenia adjusted for the mediator) and indirect effects (ie, mediational effect). Confidence intervals were calculated with the delta method. Using the khb command, the percentage of the main association explained by the mediator can also be calculated (mediated percentage). The mediated percentage is the percent attenuation in the log odds of pain after the inclusion of the potential mediator in the model, compared to the model without the mediator. Each potential mediator was included in the model individually. The pain variable used in the mediation analysis was continuous.

All regression analyses including the mediation analysis were adjusted for age, sex, education, wealth, chronic conditions, and country, except for the country-stratified analyses, which were not adjusted for country. Adjustment for the country was made by including dummy variables for each country in the model as in previous SAGE publications (38,39). The sample weighting and the complex study design were considered in all analyses. Results from the regression analyses are presented as ORs with 95% CIs. All analyses were performed with a significance level α = 0.05; therefore, p-value less than .05 was considered significant.

Results

The final sample included 14,585 adults aged ≥65 years (China n = 5 360; Ghana n = 1 975; India n = 2 441; Mexico n = 1 375; Russia n = 1 950; South Africa n = 1 484). The sample characteristics are provided in Table 1. The mean (SD) age was 72.6 (11.5) years and 55% were female. Those with sarcopenia were significantly more likely to have greater severity of pain, be older, have lower levels of education and wealth, and more chronic conditions. The prevalence of sarcopenia increased with increasing severity of pain in the overall sample and among men and women (Figure 1). For example, in the overall sample, the prevalence of sarcopenia was only 8.5% among those with no pain but this increased to 29.4% among people with extreme pain. After adjustment for potential confounders, compared to no pain, mild, moderate, severe, and extreme pain were associated with 1.42 (95%CI = 1.05–1.94), 1.43 (95%CI = 1.02–2.00), 1.92 (95%CI = 1.09–3.37), and 2.88 (95%CI = 1.10–7.54) times higher odds for sarcopenia, respectively (Figure 2). Country-wise analysis showed that a 1-unit increase in severity of pain was associated with 1.23 (95%CI = 1.12–1.35) times higher odds for sarcopenia based on a meta-analysis, and a low level of heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 9.6%; Figure 3). The presence of back pain was associated with 1.26 (95%CI = 1.05–1.51) times higher odds for sarcopenia with a low level of between-country heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%; Supplementary Figure S1). Finally, mediation analysis showed that disability (mediated percentage 18.0%), sedentary behavior (12.9%), and mobility (56.1%) were significant mediators in the association between increasing levels of pain and sarcopenia (Table 2).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (overall and by sarcopenia)

| Characteristics | Overall | Sarcopenia | p Valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||

| Pain | None | 30.0 | 33.0 | 22.4 | <.001 |

| Mild | 32.2 | 32.7 | 33.3 | ||

| Moderate | 23.4 | 22.5 | 24.9 | ||

| Severe | 13.1 | 11.3 | 17.5 | ||

| Extreme | 1.3 | 0.6 | 2.0 | ||

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 72.6 (11.5) | 71.5 (10.3) | 76.4 (12.1) | <.001 |

| Sex | Female | 55.0 | 54.1 | 50.8 | .157 |

| Male | 45.0 | 45.9 | 49.2 | ||

| Education | ≤Primary | 63.7 | 65.3 | 80.3 | <.001 |

| Secondary | 29.9 | 28.5 | 16.9 | ||

| Tertiary | 6.4 | 6.2 | 2.7 | ||

| Wealth | Poorest | 21.7 | 20.5 | 30.9 | <.001 |

| Poorer | 21.0 | 19.9 | 23.2 | ||

| Middle | 20.4 | 20.2 | 19.1 | ||

| Richer | 17.5 | 18.9 | 14.8 | ||

| Richest | 19.4 | 20.5 | 12.0 | ||

| Number of chronic conditions | 0 | 38.4 | 41.6 | 32.2 | .001 |

| 1 | 33.5 | 33.0 | 41.3 | ||

| ≥2 | 28.1 | 25.3 | 26.6 |

Notes: SD = standard deviation. Data are % unless otherwise stated.

a p-Value was calculated by Chi-squared tests except for age which used Student’s t-test.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of sarcopenia by pain severity (overall and by sex) .

Figure 2.

Association between pain severity and sarcopenia (outcome) estimated by multivariable logistic regression. Reference category is no pain. Pain was included in the model as a categorical variable. Model is adjusted for age, sex, education, wealth, chronic conditions, and country. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Figure 3.

Country-wise association between increasing severity of pain and sarcopenia (outcome) estimated by multivariable logistic regression. Pain was included in the model as a continuous variable. Models are adjusted for age, sex, education, wealth, and chronic conditions. Overall estimate was obtained by meta-analysis with fixed effects. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Table 2.

Mediators in the Association Between Increasing Severity of Pain and Sarcopenia (outcome)

| Mediator | Effect | OR (95%CI) | p Value | %Mediateda |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affect | Total | 1.22 (1.05, 1.43) | .012 | NA |

| Direct | 1.21 (1.04, 1.40) | .011 | ||

| Indirect | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) | .739 | ||

| Sleep/energy | Total | 1.22 (1.04, 1.43) | .012 | NA |

| Direct | 1.21 (1.04, 1.41) | .016 | ||

| Indirect | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) | .724 | ||

| ADL disability | Total | 1.21 (1.04, 1.41) | .013 | 18.0 |

| Direct | 1.17 (1.01, 1.35) | .034 | ||

| Indirect | 1.04 (1.00, 1.07) | .031 | ||

| Social participation | Total | 1.22 (1.05, 1.43) | .012 | NA |

| Direct | 1.22 (1.03, 1.43) | .018 | ||

| Indirect | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | .587 | ||

| Sedentary behavior | Total | 1.21 (1.04, 1.42) | .015 | 12.9 |

| Direct | 1.18 (1.01, 1.38) | .037 | ||

| Indirect | 1.03 (1.01, 1.04) | .001 | ||

| Mobility | Total | 1.23 (1.05, 1.43) | .008 | 56.1 |

| Direct | 1.09 (0.93, 1.29) | .293 | ||

| Indirect | 1.12 (1.06, 1.19) | <.001 |

Notes: ADL = activities of daily living; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Pain was included in the model as a continuous variable.

Models were adjusted for age, sex, education, wealth, chronic conditions, and country.

aMediated percentage was only calculated in the presence of a significant indirect effect.

Discussion

Main Findings

In our study using nationally representative data from 6 LMICs, we found that increasing levels of pain are associated with higher odds for sarcopenia among adults aged ≥65 years in a dose-depended manner. For example, compared to no pain, mild and moderate pain were associated with 1.42–1.43 times higher odds for sarcopenia, but the OR increased nearly 3-fold for those with extreme pain. Country-wise analysis showed that there is a low level of between-country heterogeneity in the association between increasing severity of pain and sarcopenia. Back-specific pain was associated with 1.26 times higher odds for sarcopenia. Disability (mediated percentage 18%), sedentary behavior (12.9%), and low mobility (56.1%) were significant mediators in the association between increasing levels of pain and sarcopenia. However, sleep/energy, affect, and social participation were not significant mediators. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on pain and sarcopenia from LMICs.

Interpretation of the Findings

Our study findings are in line with existing literature from HICs (16), and add to the existing literature by showing that the pain–sarcopenia relationship also exists in LMICs. Moreover, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, we have demonstrated for the first time that disability, sedentary behavior, and mobility act as potential mediating variables in the relationship. This information is important as it may aid in the development of targeted interventions.

There are several plausible pathways that may explain the pain–sarcopenia relationship. First, disability mediated 18% of the association between pain and sarcopenia. Pain has been found to increase the risk for disability (40), possibly via a reduction in the range of joint movements as a consequence of reflex inhibition of skeletal muscles. Disability, in turn, may result in muscle weakness and impaired physical function (40) through low levels of physical activity and poor nutrition (41–43). Second, sedentary behavior explained 12.9% of the pain–sarcopenia association. Pain may lead to increased sedentary behavior via avoidance of physically active pursuits that may exacerbate pain, or sitting per se to alleviate pain. Sedentary behavior, in turn, may increase the risk for sarcopenia (44) through increased adiposity that may increase inflammation, which could contribute to muscle loss (44). Next, low mobility was identified in the present analysis as the most influential factor in the pain–sarcopenia association, explaining 56.3% of the association. Pain may lead to mobility limitations owing to the exacerbation of pain during function tasks that may impact the maintenance of stability and controlled transfer of body weight (45). In turn, mobility limitations likely lead to sarcopenia via lower levels of physical activity and higher levels of sedentary behavior, as previously discussed. Finally, apart from the potential mediators identified in the present study, some medications prescribed to aid in pain relief, such as glucocorticoids have been associated with weight gain and muscle weakness (46), and thus may also increase the risk for sarcopenia. Furthermore, systemic chronic inflammation is, in some cases, related to chronic pain (47,48), and chronic low-grade inflammation might be one of many elements in a presumably complex mechanism underlying sarcopenia (49,50).

It is also possible that sarcopenia per se increases the risk for chronic pain. For example, sarcopenia has been found to be associated with increased risks for rotator cuff tendon diseases (characterized by chronic pain) (51). Moreover, sarcopenia is similar to a subclinical state of inflammation, wherein increased levels of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNFα, might potentiate pain sensitivity of the musculoskeletal system (52).

It is also worth noting here that despite plausible pathways, sleep/energy, affect, and social participation were not identified as significant mediators in the pain–sarcopenia relationship. For example, sleep problems can theoretically be a mediator as the pain has been shown to increase the risk for sleep problems, while sleep problems, in turn, have been implicated in the development of sarcopenia (53,54). Further research is needed to confirm or refute our findings in relation to the studied mediating variables.

In terms of location-specific pain (back pain), we found that back pain is associated with 1.26 times higher odds for sarcopenia. Back pain has been associated with sarcopenia in previous studies from HICs (55). While all types of pain can cause immobility or disability that increase risk for sarcopenia, it is possible for back pain to have a particularly pronounced effect on these conditions. For example, in one study in a sample of 96 middle-aged to older adults, it was found that physical activity levels and disability were more affected in those with low back pain compared to those with neck pain (56).

Implications of the Study Findings

Findings from this study potentially suggest that not only interventions that address pain but also those that aim to reduce sedentary behavior, disability, and improve mobility among those with pain in LMICs may aid in the prevention of sarcopenia. The WHO estimates that 5.5 billion people (more than 80% of the global population) do not have access to treatments for moderate to severe pain, and the majority of these individuals live in LMICs (57). This is due, in part, to a weak health system and insufficient infrastructure but also other barriers, such as fractured diagnostics landscapes and shortages or maldistribution of the health workforce, as well as multidimensional, logistical, and financial challenges: high costs, lack of quality assurance, frequent stock-outs, and complex regulatory pathways (58). Key areas for improving pain management in LMICs include advocacy, improving treatment availability, and education (18). Furthermore, it may be prudent to target interventions toward displacing sedentary leisure pursuits with physical activity, specifically physical exercise programs, among people with pain. Yoga and tai chi exercise programs have been shown to be feasible to implement in LMICs and among those with pain, reduce the risk of disability, as well as improve mobility among those with mobility limitations (59,60). Results from a meta-analysis on 333 participants showed that both progressive resistance and aerobic training programs were effective in nonspecific low back pain reduction (61). In addition, results from a meta-analysis on 561 healthy older adults with sarcopenia showed that resistance training programs are effective in improving body composition and function of the musculoskeletal system (62). Physical activity programs might also be effective in lowering chronic low-grade inflammation (50), which could be related to chronic pain and sarcopenia as mentioned above. Finally, another potential strategy could be to target improvements in rehabilitation services in LMICs so that people with pain could be more active.

Strengths and Limitations

The use of a large representative data set across 6 LMICs, and the quantification of the degree to which potential mediating variables may explain the pain–sarcopenia relationship are clear strengths of the present study. However, findings must be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations. First, this study was cross-sectional in nature, and thus, temporal associations and causality could not be determined. Future longitudinal studies on this topic from LMICs are necessary to address this issue. Second, some of the variables were self-reported, potentially introducing bias (eg, recall social desirability bias) into the findings. For example, it is known that people with depression tend to underreport their symptoms (63). Moreover, multiple self-report items have not been previously validated (eg, pain, mobility, sleep/energy). Third, we did not have data on nutritional status and/or food intake, and thus, the influence of these factors on the association between pain and sarcopenia could not be assessed. Fourth, although the countries included in this study were all LMICs at the time of the survey, they were not selected randomly. In addition, only one country was classified as a low-income country. Thus, the results of our study are unlikely to be generalizable to all LMICs. Fifth, participants in nursing homes or other institutions, who may be at higher risk for pain and sarcopenia, were not included in our study. Thus, our study results may not be generalizable to the entire population. Next, because of the way in which the question on pain was phrased, we were only able to assess general intensity of pain but not frequency of pain, while it is unknown whether pain was of chronic nature or not. Moreover, there is no gold standard measurement of pain related to sarcopenia. Previous studies on this topic have used similar but different measures of pain (16), and thus, it is possible for results to have changed slightly if a different measure of pain was used. Finally, while the large sample size is a clear strength of this study, it is important to note that it also increases the risk of type I error.

Conclusion

In this large nationally representative sample of older adults from 6 LMICs, increasing the severity of pain was associated with higher odds for sarcopenia. Moreover, disability, sedentary behavior, and lower mobility were identified as potential mediating variables. Addressing pain itself or the identified potential mediators among people with pain may lead to a reduction in sarcopenia in older people in LMICs, but clearly, longitudinal and intervention studies from this setting are necessary before concrete recommendations can be made.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This paper uses data from WHO’s Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE). SAGE is supported by the U.S. National Institute on Aging through Interagency Agreements OGHA 04034785, YA1323–08-CN-0020, Y1-AG-1005–01 and through research grants R01-AG034479 and R21-AG034263.

Contributor Information

Lee Smith, Centre for Health Performance and Wellbeing, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, UK.

Guillermo F López Sánchez, Division of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Department of Public Health Sciences, School of Medicine, University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain.

Nicola Veronese, Department of Internal Medicine, Geriatrics Section, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy.

Pinar Soysal, Department of Geriatric Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Bezmialem Vakif University , Istanbul, Turkey.

Karel Kostev, University Clinic of Marburg, Marburg, Germany.

Louis Jacob, Research and Development Unit, Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu, CIBERSAM, ISCIII, Dr. Antoni Pujadas, Sant Boi de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain; Faculty of Medicine, University of Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France.

Masoud Rahmati, Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, Faculty of Literature and Human Sciences, Lorestan University, Khoramabad, Iran.

Agnieszka Kujawska, Department of Exercise Physiology and Functional Anatomy, Ludwik Rydygier Collegium Medicum in Bydgoszcz Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Bydgoszcz, Poland.

Mark A Tully, School of Medicine. Ulster University, Londonderry, Northern Ireland, UK.

Laurie Butler, Centre for Health Performance and Wellbeing, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, UK.

Jae Il Shin, Department of Pediatrics, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea.

Ai Koyanagi, Research and Development Unit, Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu, CIBERSAM, ISCIII, Dr. Antoni Pujadas, Sant Boi de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain; ICREA, Barcelona, Spain.

Funding

G.F.L.S. is funded by the European Union – Next Generation EU.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1. Rosenberg IH. Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance. J Nutr. 1997;127(5):990S–991S. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.5.990s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Patel HP, Syddall HE, Jameson K, et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older people in the UK using the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) definition: findings from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study (HCS). Age Ageing. 2013;42(3):378–384. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shafiee G, Keshtkar A, Soltani A, Ahadi Z, Larijani B, Heshmat R. Prevalence of sarcopenia in the world: a systematic review and meta-analysis of general population studies. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2017;16(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40200-017-0302-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith L, López-Sánchez GF, Jacob L, et al. Objectively measured far vision impairment and sarcopenia among adults aged≥ 65 years from six low-and middle-income countries. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33(11):2995–3003. doi: 10.1007/s40520-021-01841-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Veronese N, Demurtas J, Soysal P, et al. Sarcopenia and health-related outcomes: an umbrella review of observational studies. Eur Geriatr Med. 2019;10(6):853–862. doi: 10.1007/s41999-019-00233-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Janssen I, Shepard DS, Katzmarzyk PT, Roubenoff R. The healthcare costs of sarcopenia in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(1):80–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. United Nations. World population ageing 2019 highlights. World Popul ageing. 2019. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Highlights.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8. Volpato S, Bianchi L, Cherubini A, et al. Prevalence and clinical correlates of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older people: application of the EWGSOP definition and diagnostic algorithm. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(4):438–446. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Steffl M, Bohannon RW, Sontakova L, Tufano JJ, Shiells K, Holmerova I. Relationship between sarcopenia and physical activity in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:835. doi:10.2147%2FCIA.S132940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Trajanoska K, Schoufour JD, Darweesh SKL, et al. Sarcopenia and its clinical correlates in the general population: the Rotterdam study. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33(7):1209–1218. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Esparza Montero MA. Influence of the strength of the ankle plantar flexors on dynamic balance in 55-65-year-old women. Atena J Public Heal. 2021;3:3. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kushkestani M, Parvani M, Ghafari M, Avazpoor Z. The role of exercise and physical activity on aging-related diseases and geriatric syndromes. Sport TK-Revista Euroam Ciencias del Deport. 2022;11:6. doi: 10.6018/sportk.464401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. IASP. IASP announces revised definition of pain. 2020. Accessed June 10, 2022. https://www.iasp-pain.org/publications/iasp-news/iasp-announces-revised-definition-of-pain/

- 14. Wernli K, Tan JS, O’Sullivan P, Smith A, Campbell A, Kent P. Does movement change when low back pain changes? A systematic review. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 2020;50(12):664–670. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2020.9635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen Y, Campbell P, Strauss VY, Foster NE, Jordan KP, Dunn KM. Trajectories and predictors of the long-term course of low back pain: cohort study with 5-year follow-up. Pain. 2018;159(2):252. doi:10.1097%2Fj.pain.0000000000001097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lin T, Dai M, Xu P, et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia in pain patients and correlation between the 2 conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23(5):902.e1–902.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2022.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jackson T, Thomas S, Stabile V, Han X, Shotwell M, McQueen K. Prevalence of chronic pain in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2015;385:S10. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60805-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morriss WW, Roques CJ. Pain management in low-and middle-income countries. BJA Educ. 2018;18(9):265. doi:10.1016%2Fj.bjae.2018.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kowal P, Chatterji S, Naidoo N, et al. Data resource profile: the World Health Organization Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(6):1639–1649. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16–31. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee RC, Wang Z, Heo M, Ross R, Janssen I, Heymsfield SB. Total-body skeletal muscle mass: development and cross-validation of anthropometric prediction models. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(3):796–803. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.3.796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Studenski SA, Peters KW, Alley DE, et al. The FNIH sarcopenia project: rationale, study description, conference recommendations, and final estimates. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(5):547–558. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tyrovolas S, Koyanagi A, Olaya B, et al. Factors associated with skeletal muscle mass, sarcopenia, and sarcopenic obesity in older adults: a multi-continent study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2016;7(3):312–321. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ortiz O, Russell M, Daley TL, et al. Differences in skeletal muscle and bone mineral mass between black and white females and their relevance to estimates of body composition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55(1):8–13. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/55.1.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Koyanagi A, Stickley A. The association between psychosis and severe pain in community-dwelling adults: findings from 44 low-and middle-income countries. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;69:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zimmer Z, Fraser K, Grol-Prokopczyk H, Zajacova A. A global study of pain prevalence across 52 countries: examining the role of country-level contextual factors. Pain. 2022;163(9):1740–1750. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;220:233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Feeny D, Furlong W, Boyle M, Torrance GW. Multi-attribute health status classification systems. PharmacoEcon. 1995;7(6):490–502. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199507060-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kind P. The EuroQol instrument. An index of health-related quality of life. Qual Life Pharmacoeconomics Clin Trials. 1996. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1573950399913842816?lang=en [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nuevo R, Chatterji S, Verdes E, Naidoo N, Arango C, Ayuso-Mateos JL. The continuum of psychotic symptoms in the general population: a cross-national study. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(3):475–485. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nuevo R, Van Os J, Arango C, Chatterji S, Ayuso-Mateos JL. Evidence for the early clinical relevance of hallucinatory-delusional states in the general population. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127(6):482–493. doi: 10.1111/acps.12010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stubbs B, Koyanagi A, Schuch F, et al. Physical activity levels and psychosis: a mediation analysis of factors influencing physical activity target achievement among 204 186 people across 46 low-and middle-income countries. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(3):536–545. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Firth J, et al. Relationship between sedentary behavior and depression: a mediation analysis of influential factors across the lifespan among 42,469 people in low-and middle-income countries. J Affect Disord. 2018;229:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Koyanagi A, Moneta MV, Garin N, et al. The association between obesity and severe disability among adults aged 50 or over in nine high-income, middle-income and low-income countries: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e007313–e007313. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Orimo H, Ito H, Suzuki T, Araki A, Hosoi T, Sawabe M. Reviewing the definition of “elderly.”. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2006;6(3):149–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2006.00341.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Breen R, Karlson KB, Holm A. Total, direct, and indirect effects in logit and probit models. Sociol Methods Res. 2013;42(2):164–191. doi: 10.1177/0049124113494572 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Koyanagi A, Lara E, Stubbs B, et al. Chronic physical conditions, multimorbidity, and wmild cognitive impairment in low-and middle-income countries. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(4):721–727. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Koyanagi A, Garin N, Olaya B, et al. Chronic conditions and sleep problems among adults aged 50 years or over in nine countries: a multi-country study. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Landi F, Russo A, Liperoti R, et al. Daily pain and functional decline among old-old adults living in the community: results from the ilSIRENTE Study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(3):350–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sánchez Castillo S, Smith L, Díaz Suárez A, López Sánchez GF. Physical activity behaviour in people with COPD residing in Spain: a cross-sectional analysis. Lung. 2019;197(6):769–775. doi: 10.1007/s00408-019-00287-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Seo JH, Lee Y. Association of physical activity with sarcopenia evaluated based on muscle mass and strength in older adults: 2008–2011 and 2014– 2018 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-02900-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Verstraeten LMG, van Wijngaarden JP, Pacifico J, Reijnierse EM, Meskers CGM, Maier AB. Association between malnutrition and stages of sarcopenia in geriatric rehabilitation inpatients: RESORT. Clin Nutr. 2021;40(6):4090–4096. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2021.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gianoudis J, Bailey CA, Daly RM. Associations between sedentary behaviour and body composition, muscle function and sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(2):571–579. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2895-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Menz HB, Dufour AB, Casey VA, et al. Foot pain and mobility limitations in older adults: the Framingham Foot Study. J. Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(10):1281–1285. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yasir M, Goyal A, Sonthalia S.Corticosteroid adverse effects. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL); 2022. https://europepmc.org/article/NBK/nbk531462 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Franceschi C, Campisi J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-associated diseases. J. Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(Suppl_1):S4–S9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhou WBS, Meng J, Zhang J. Does low grade systemic inflammation have a role in chronic pain? Front Mol Neurosci. 2021;14:1–10. doi:10.3389%2Ffnmol.2021.785214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pan L, Xie W, Fu X, et al. Inflammation and sarcopenia: a focus on circulating inflammatory cytokines. Exp Gerontol. 2021;154:111544. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2021.111544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Beyer I, Mets T, Bautmans I. Chronic low-grade inflammation and age-related sarcopenia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2012;15(1):12–22. doi: 10.1097/mco.0b013e32834dd297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Han DS, Wu WT, Hsu PC, Chang HC, Huang KC, Chang KV. Sarcopenia is associated with increased risks of rotator cuff tendon diseases among community-dwelling elders: a cross-sectional quantitative ultrasound study. Front Med. 2021;8:630009. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.630009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chhetri JK, de Souto Barreto P, Fougère B, Rolland Y, Vellas B, Cesari M. Chronic inflammation and sarcopenia: a regenerative cell therapy perspective. Exp Gerontol. 2018;103:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2017.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hester J, Tang NKY. Insomnia co-occurring with chronic pain: clinical features, interaction, assessments and possible interventions . Rev Pain. 2008;2(1):2–7. doi: 10.1177/204946370800200102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Szlejf C, Suemoto CK, Drager LF, et al. Association of sleep disturbances with sarcopenia and its defining components: the ELSA-Brasil study. Brazilian J Med Biol Res. 2021;54(12):e11539, 1–9. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X2021e11539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sakai Y, Matsui H, Ito S, et al. Sarcopenia in elderly patients with chronic low back pain. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 2017;3(4):195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.afos.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Soysal M, Bilge K, Arda MN. Assessment of physical activity in patients with chronic low back or neck pain. Turk Neurosurg. 2013;23(1):75–80. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.6885-12.0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Seya MJ, Gelders SFAM, Achara OU, Milani B, Scholten WK. A first comparison between the consumption of and the need for opioid analgesics at country, regional, and global levels. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2011;25(1):6–18. doi: 10.3109/15360288.2010.536307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. World Economic Forum. How to improve access to cancer medicines in low and middle-income countries. 2022. Accessed July 24, 2022. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/04/imrpove-access-cancer-medicines/

- 59. Sherman KJ, Wellman RD, Hawkes RJ, Phelan EA, Lee T, Turner JA. T’ai Chi for chronic low back pain in older adults: a feasibility trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2020;26(3):176–189. doi: 10.1089/acm.2019.0438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Groessl EJ, Maiya M, Schmalzl L, Wing D, Jeste DV. Yoga to prevent mobility limitations in older adults: feasibility of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0988-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wewege MA, Booth J, Parmenter BJ. Aerobic vs. resistance exercise for chronic non-specific low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2018;31(5):889–899. doi: 10.3233/BMR-170920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chen N, He X, Feng Y, Ainsworth BE, Liu Y. Effects of resistance training in healthy older people with sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. 2021;18(1):1–19. doi: 10.1186/s11556-021-00277-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hunt M, Auriemma J, Cashaw ACA. Self-report bias and underreporting of depression on the BDI-II. J Pers Assess. 2003;80(1):26–30. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8001_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.