Abstract

Background

Geographic variation in high-cost medical procedure utilization in the USA is not fully explained by patient factors but may be influenced by the supply of procedural physicians and marketing payments.

Objective

To examine the association between physician supply, medical device–related marketing payments to physicians, and utilization of knee arthroplasty (KA) and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) within hospital referral regions (HRRs).

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of data from the 2018 CMS Open Payments database and procedural utilization data from the CMS Provider Utilization and Payment database.

Participants

Medicare-participating procedural cardiologists and orthopedic surgeons.

Main Measures

Regional rates of PCIs and KAs per 100,000 Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries were estimated after adjustment for beneficiary demographics.

Key Results

Across 306 HRRs, there were 109,301 payments (value $17,554,728) to cardiologists for cardiac stents and 68,132 payments (value $40,492,126) to orthopedic surgeons for prosthetic knees. Among HRRs, one additional interventional cardiologist was associated with an increase of 12.9 (CI, 9.3–16.5) PCIs per 100,000 beneficiaries, and one additional orthopedic surgeon was associated with an increase of 20.6 (CI, 16.9–24.4) KAs per 100,000 beneficiaries. A $10,000 increase in gift payments from stent manufacturers was associated with an increase of 26.0 (CI, 5.1–46.9) PCIs per 100,000 beneficiaries, while total and service payments were not associated with greater regional PCI utilization. A $10,000 increase in total payments from knee prosthetic manufacturers was associated with an increase of 2.9 (CI, 1.4–4.5) KAs per 100,000 beneficiaries, while a similar increase in gift and service payments was associated with an increase of 14.5 (CI, 5.0–24.1) and 3.4 (CI, 1.6–5.2) KAs, respectively.

Conclusions

Among Medicare FFS beneficiaries, regional supply of physicians and receipt of industry payments were associated with greater use of PCIs and KAs. Relationships between payments and procedural utilization were more consistent for KAs, a largely elective procedure, compared to PCIs, which may be elective or emergent.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-023-08101-x.

KEY WORDS: medical devices, procedure utilization, marketing payments, cardiology, orthopedics, percutaneous coronary intervention, joint arthroplasty, conflict of interest

Introduction

Regional variation in the use of healthcare services is well established 1,2. For many common chronic conditions, there are both high-cost invasive procedural treatments (e.g., percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI] for coronary artery disease and knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis) and lower-cost pharmaceutical and office-based treatments available. For most conditions, clinical guidelines recommend reserving the use of high-cost invasive procedures for more severe disease after failure to improve with other less-intensive treatments. Despite guidelines, numerous prior studies demonstrate that regional variation in procedural utilization is not fully explained by patient factors, suggesting that factors beyond clinical indication likely influence the decision to perform these procedures3–7.

Studies from the 1990s and early 2000s have shown that supply-side factors, such as physician supply and physician characteristics, may influence the use of invasive procedures and healthcare delivery8–11. The creation of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Open Payment Program has allowed for the study of another possible driver of procedure utilization, marketing payments from pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers. Receipt of payments from pharmaceutical manufacturers has been associated with greater prescribing of marketed medications and increased requests by physicians to add drugs to hospital formularies12–15. However, less is known about the impact of medical device manufacturer payments. Device-related payments exceed pharmaceutical payments in overall and average value16–20. Medical devices differ from pharmaceuticals in important ways. Unlike pharmaceuticals, they are not dispensed directly to patients but are used by clinicians to facilitate invasive procedures. Furthermore, the unit cost of an implanted medical device, such as prosthetics and coronary stents, is typically thousands of dollars. Recent research suggests marketing payments may influence brand selection of medical devices21, but whether payments are associated with increased utilization of device-related procedures is unknown. Understanding this relationship, particularly in the setting of elective procedures, is important because overtreatment is associated with patient harm and health care waste22.

Therefore, we linked CMS Open Payments data and procedural utilization data for physicians performing cardiac catheterizations, PCIs, and knee arthroplasties and participated in Medicare in 2018 in order to examine the association between medical device manufacturer payments, physician supply, and procedure utilization within healthcare referral regions (HRRs). We examined two procedures, PCI and knee arthroplasty, as they are among the most common and most expensive device-related procedures performed among Medicare beneficiaries, and prior work has shown wide regional variation in their use5,8,9. We hypothesized that both medical device–related payments and physician supply would be associated with higher rates of regional procedure utilization, with a stronger association for knee arthroplasties which are nearly always elective compared to PCIs which may be performed emergently or electively.

Study Data and Methods

Overview

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional analysis linking the following 2018 CMS databases: the Open Payments database and Physician & Other Practitioners—by Provider Public Use File, and Geographic Variation Public Use File23–25.We examined the association between device-related marketing payments, physician supply, and rates of procedure utilization at the HRR level. HRRs are geographic areas defined by healthcare markets for tertiary care services such as receipt of advanced cardiovascular procedures and surgeries. We examined regional rather than individual utilization for three reasons. First, prior studies have demonstrated regional variation in procedural utilization. Second, individual physician procedure rates may be influenced by case-mix and degree of participation in Medicare. Third, marketing payments often target key opinion leaders whose influence may have downstream impacts on the clinical practice of peers or trainees which would not be captured by individual-level analyses26–29. This study reports only publicly available data and thus is not subject to federal human subject regulations for institutional review board review.

Regional Procedure Utilization

Procedure utilization data for PCIs and knee arthroplasties was obtained from the 2018 CMS Physician & Other Practitioners—by Provider Public Use File30, which provides clinician-level aggregate counts of services and procedures provided to Medicare beneficiaries, grouped by Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes (Appendix A1). The database contains 100% final-action physician/supplier Part B non-institutional line items for the Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) population. We aggregated clinician-level procedures to HRRs based on clinician practice ZIP codes31.

Physician Supply

To establish a measure of regional physician supply, we identified all cardiologists who performed at least 11 cardiac catheterizations or PCIs and all orthopedic surgeons who performed at least 11 knee arthroplasties on Medicare FFS beneficiaries using the 2018 CMS Physician & Other Practitioners—by Provider Public Use File30. We defined physician supply based on procedural performance, rather than specialty, to avoid misclassification of subspecialists who do not routinely perform the procedures of interest (e.g., orthopedists who specialize in other joint surgeries). We then calculated the number of specialists per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries for each HRR.

Medical Device Manufacturer Payments

To identify device manufacturers of interest, we first identified all coronary stents and knee prostheses listed in the Food and Drug Administration Product Code Classification Database32. We then linked products to manufacturers of each unique device using the Food and Drug Administration Global Unique Device Identification Database33. Each coronary stent and knee prosthesis manufacturer was then matched to the 2018 CMS Open Payments database by company name23.

We identified all payments made by medical device manufacturers listed in the Open Payments database to interventional cardiologists and orthopedic surgeons identified from the Physician & Other Practitioners – by Provider Public Use File. We excluded research payments and payments for ownership and royalties, which reflect different types of financial relationships than marketing (e.g., income from patents).

Payments linked to product types other than medical devices (e.g., pharmaceuticals) were also excluded. We grouped payment types into two broad categories: gifts and services. Gift payments included entertainment, food/beverage, gift, travel/lodging, education, non-research grants, and charitable contributions. Service payments included consulting fees, honoraria, compensation for services other than consulting, and compensation for serving as faculty or as a speaker for an accredited or non-accredited continuing education program, and space rental or facility fees. We calculated payments in each HRR per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries.

Covariates

We used the CMS Geographic Variation Public Use File to identify HRR-level demographics of Medicare FFS enrollees of all ages in the year 2018 including the number of FFS beneficiaries, percent eligible for Medicaid, average hierarchical conditioning category score, average age, percent female, and percent by race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, African American, Hispanic, and other)34.

Statistical Analysis

We present descriptive characteristics on procedure utilization rates, physician supply, and medical device manufacturer payments nationally and across HRRs. Marketing payments are presented overall and stratified by type into payments for gifts and payments for services.

We used multivariable linear regression models fitted using ordinary least squares to analyze the association between procedural physician supply, medical device manufacturer payments, and procedure utilization rates in 2018 at the level of the HRR, including the aforementioned covariates. Then, we estimated the impact of differing quintiles of regional physician supply and of marketing payments on predicted procedural utilization by calculating post-estimation marginal means.

All regression model estimates are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All analyses were conducted between January 2020 and January 2023 using Microsoft Access and Stata-SE version 16.

Results

The study population included 9,140 cardiologists performing PCIs and cardiac catheterizations, and 7,076 orthopedic surgeons performing knee arthroplasties across 306 HRRs. Of these, 7,634 cardiologists and 5,947 orthopedic surgeons received payments.

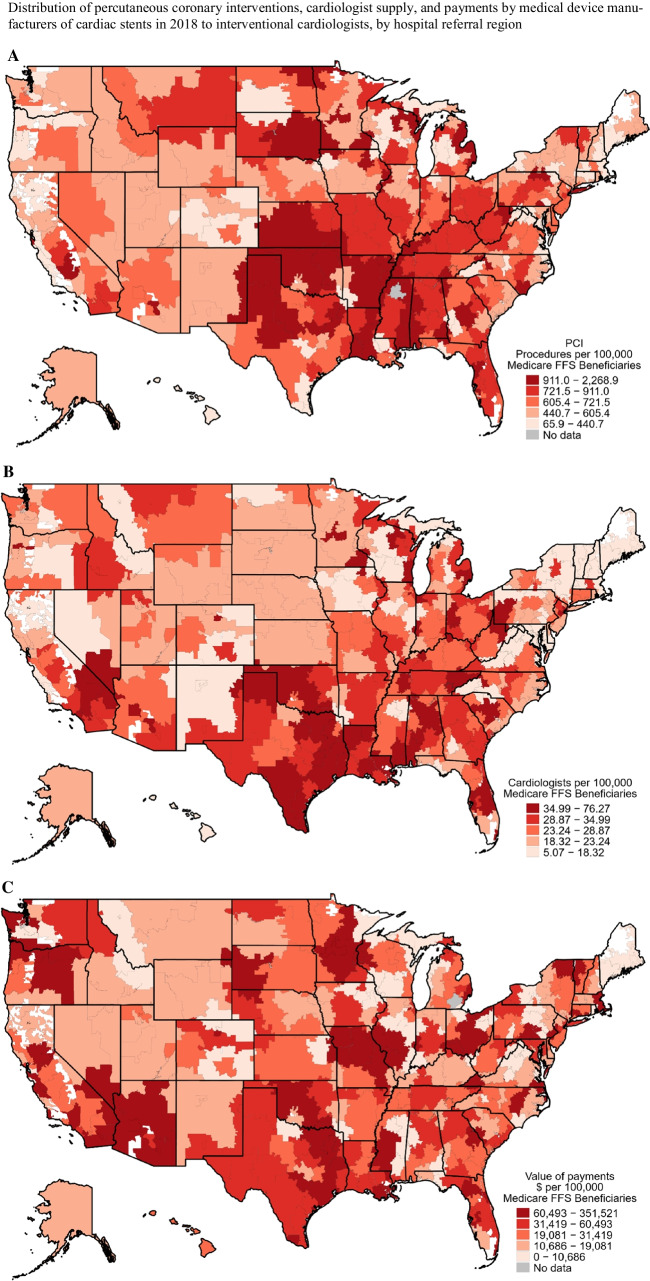

In 2018, the median annual PCI rate across HRRs was 650.2 (IQR, 491.7 to 852.2) per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries, with the highest utilizing HRRs clustered in the Midwest (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

A Number of percutaneous coronary interventions per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries in each healthcare referral region. B Map showing number of cardiologists performing cardiac catheterizations per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries in each healthcare referral region. C Payments in $ per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries from medical device manufacturers of cardiac stents to cardiologists in each healthcare referral region. For all panels, darker red indicates higher quintile values.

The median number of cardiologists performing PCIs per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries was 26.1 (IQR, 19.5 to 22.4) (Fig. 1B).

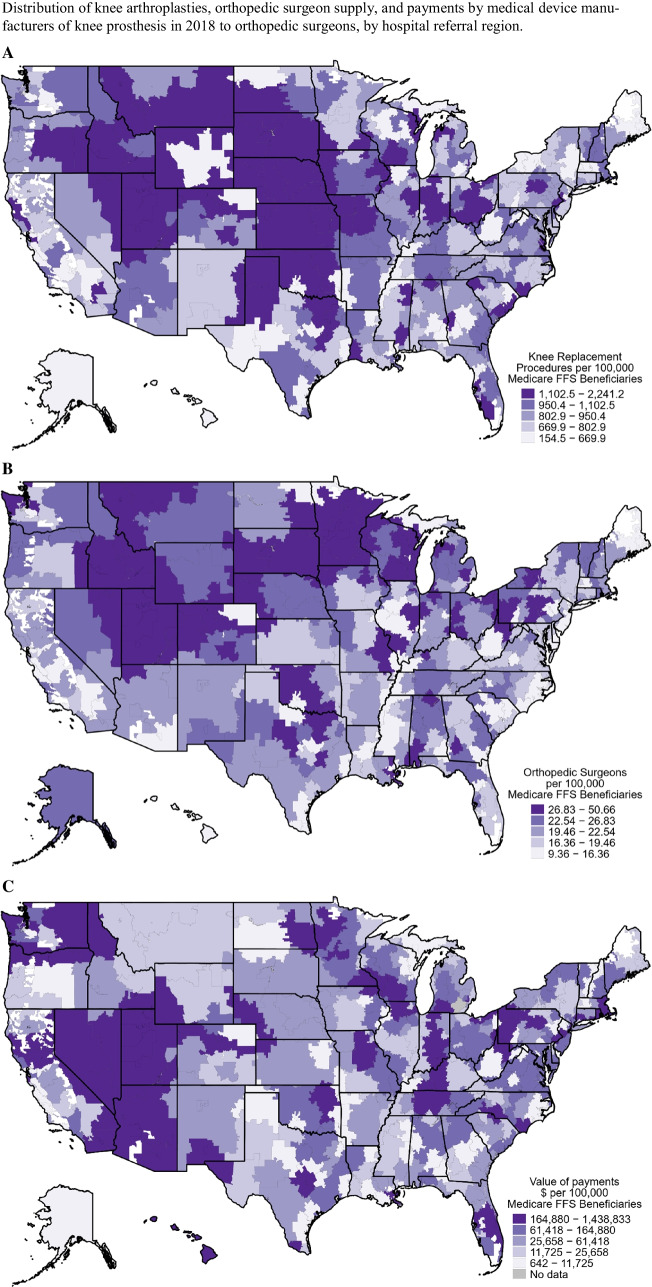

The median annual knee arthroplasty rate across HRRs was 874.7 (IQR, 719.4 to 1050.5) per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries with the highest utilizing HRRs clustered in the Midwest, Northwest, and Southwest (Fig. 2A). The median number of orthopedic surgeons performing knee arthroplasties per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries was 21.0 (IQR, 17.1 to 25.7) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

A Number of knee arthroplasties per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries in each healthcare referral region. B Map showing number of orthopedic surgeons performing knee arthroplasties per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries in each healthcare referral region. C Payments in $ per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries from medical device manufacturers of knee joints to orthopedic surgeons in each healthcare referral region. For all panels, darker purple indicates higher quintile values.

Among the 306 HRRs, there were 109,301 payments to cardiologists by cardiac stent manufacturers totaling $17,554,728. The median value of payments from cardiac stent manufacturers was $19,193 per HRR (IQR, $6,997 to $58,057) (Table 1). Within the top quintile of payments by cardiac stent manufacturers, the median value of payments was $110,610 (IQR, $79,161 to $153,012) per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries while the median value of the lowest quintile was $5,803 (IQR, $3,527 to $8,249) per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries (Fig. 1C).

Table 1.

Marketing Payments from Medical Device Manufacturers to Cardiologists and Orthopedic Surgeons in 2018

| Cardiac stent manufacturers | Prosthetic knee manufacturers | |

|---|---|---|

| Total value of payments, $ | ||

| All | 17,554,728 | 40,492,126 |

| Gifts* | 8,303,645 | 9,194,378 |

| Services† | 9,251,083 | 31,297,747 |

| Median value of payments to HRRs, $ [IQR] | ||

| All | 19,193 [6,997 to 58,057] | 29,013 [7,203 to 157,150] |

| Gifts | 13,410 [63,36 to 28,069] | 15,031 [5,406 to 37,576] |

| Services | 2480 [0 to 23,952] | 12,275 [0 to 122,150] |

| Median value of payments to HRRs, $ per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries [IQR] | ||

| All | 23,569 [12,146 to 48,759] | 35,546 [15,253 to 128,079] |

| Gifts | 18,760 [10,693 to 31,006] | 19,241 [10,798 to 30,282] |

| Services | 2408 [0 to 19,179] | 14,283 [0 to 99,820] |

*Gift payments include charitable contribution, entertainment, food/beverage, gift, travel/lodging, education, and non-research grants

†Service payments include consulting fee; honoraria; compensation for services other than consulting, including serving as faculty or as a speaker at an event other than a continuing education program; compensation for serving as faculty or as a speaker for an unaccredited and a non-certified continuing education program; and compensation for serving as faculty or as a speaker for an accredited or a certified continuing education program

There were 68,132 payments to orthopedic surgeons related to prosthetic knees totaling $40,492,126. The median value of payments from prosthetic knee manufacturers was $29,013 per HRR (IQR, $7,203 to $157,150) (Table 1). The median value of the top quintile of payments by knee prosthetic manufacturers was $259,979 (IQR, $201,212 to $320,774) per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries while the median value of the lowest quintile was $6,268 (IQR, $3,378 to $9,521) per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries (Fig. 2C). Across groups, gift-related payments had a higher median value than service payments (Table 1).

Association Between Physician Supply and Procedure Utilization

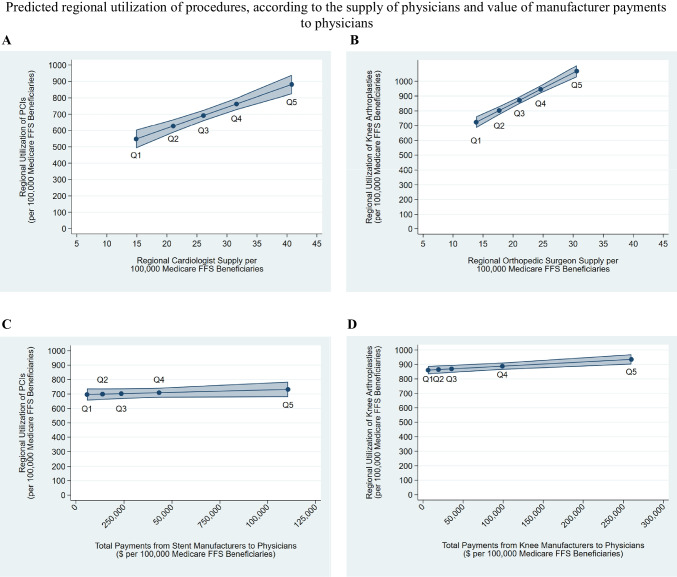

In multivariable regression models, increasing the supply of interventional cardiologists by 1 per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries in an HRR was associated with an increase in PCI utilization rate of 12.9 procedures (CI, 9.3 to 16.5) per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries (Table 2). Similarly, increasing the supply of orthopedic surgeons by 1 per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries in an HRR was associated with an increase in knee arthroplasty utilization rates of 20.6 procedures (CI, 16.9 to 24.4) per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries. Figure 3A shows the predicted mean number of PCIs per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries performed across HRRs if the supply of cardiologists for each HRR was at the median of each quintile for overall cardiologist supply. Figure 3B shows the same relationships for orthopedic surgeons and knee arthroplasties.

Table 2.

Association Between the Value of Medical Device Manufacturer Payments to Physicians, Regional Physician Supply, and Regional Utilization Of Procedures in 2018

| Change in regional procedure rate per 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries in a hospital referral region [95% CI] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | Knee arthroplasty | |

| Medical device manufacturer payments | ||

| $10,000 increase in total device-related payments per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries | 3.4 [-2.9 to 9.6] | 2.9 [1.4 to 4.5] |

| $10,000 increase in gift device–related payments per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries | 26.0 [5.1 to 46.9] | 14.5 [5.0 to 24.1] |

| $10,000 increase in service device–related payments per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries | 1.7 [-6.2 to 9.6] | 3.4 [1.6 to 5.2] |

| Procedural physician supply | ||

| Increase of 1 physician per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries | 12.9 [9.3 to 16.5] | 20.6 [16.9 to 24.4] |

Estimates derived from multivariate linear regression models in which the dependent variable was regional procedure rate per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries, the independent variable was total payments ($10,000s of dollars per 100,0000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries) from device companies to physicians, and controls at the HRR level included the physician supply (number of interventional cardiologists for percutaneous coronary interventions and orthopedic surgeons for knee arthroplasties) per 100,000 FFS Medicare beneficiaries, percent eligible for Medicaid, average HCC score, average age of Medicare FFS beneficiaries, percent female, percent non-Hispanic White, percent African American, and percent Hispanic

Figure 3.

A Predicted regional utilization of percutaneous coronary interventions in an average HRR if the supply of regional cardiologists per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries was at each quintile value for overall cardiologist supply. B Predicted regional utilization of knee arthroplasties in an average HRR if the supply of regional orthopedic surgeons per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries was at each quintile value for overall orthopedic surgeon supply. C Predicted regional utilization of percutaneous coronary interventions in an average HRR if the total number of payments per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries from stent manufacturers to cardiologists in that region was at each quintile value for overall payments from stent manufacturers. D Predicted regional utilization of knee arthroplasties in an average HRR if the total number of payments per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries from knee manufacturers to orthopedic surgeons in that region was at each quintile value for overall payments from knee manufacturers. For all panels, Q1 represents the lowest quintile and Q5 represents the highest.

Association Between Medical Device Manufacturer Payments and Procedure Utilization

For PCIs, total payments from stent manufacturers were not significantly associated with an increase in procedure utilization (coeff, 3.4; 95% CI, − 2.9 to 9.6). Gift payments from stent manufacturers were associated with an increase in procedure utilization, but service payments were not (Table 2). An increase in gift payments from stent manufacturers to interventional cardiologists by $10,000 per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries was associated with an increase in PCI utilization rates of 26.0 procedures (CI, 5.1 to 46.9) per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries. Figure 3C shows the predicted number of PCIs performed across HRRs if the payments from stent manufacturers to each HRR was at the median of each quintile of overall industry payments from stent manufacturers.

For knee arthroplasties, all payment categories were associated with an increase in procedure utilization rates (Table 2). An increase in total payments from knee prosthetic manufacturers to orthopedic surgeons by $10,000 per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries was associated with an increase in knee arthroplasty utilization rates of 2.9 procedures (CI, 1.4 to 4.5) per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries. An increase in gift payments from knee prosthetic manufacturers by $10,000 per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries was associated with an increase in knee arthroplasty utilization rates of 14.5 procedures (CI, 5.0 to 24.1) per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries, while a similar increase in service payments was associated with a smaller increase in knee arthroplasty utilization rates of 3.4 procedures (CI, 1.6 to 5.2) per 100,000 Medicare FFS beneficiaries. Figure 3D shows the predicted number of knee arthroplasties performed across HRRs if the payments from knee manufacturers to each HRR was at the median of each quintile of overall industry payments from knee manufacturers.

Discussion

In this national study of cardiologists and orthopedic surgeons participating in Medicare, both regional supply of procedural physicians and receipt of device-related gift payments were associated with greater use of both knee arthroplasty and PCI. Medical device–related total and service payments were associated with increased rates of knee arthroplasty but not PCI. As knee arthroplasty is universally an elective planned procedure while PCI may be elective or urgent, one possible explanation is that while physician supply may have broad influence on the decision to perform procedures, marketing payments of all categories may be more likely to influence elective procedures.

The finding that greater regional physician supply is associated with greater procedure utilization is consistent with prior studies from the 2000s and earlier, which were unable to account for the additional supply-side factor of industry marketing10,11,35. Procedural physician supply is highly variable; the HRRs with the highest supply have ten times as many physicians per capita than the HRRs with the lowest supply. Since our analyses adjusted for regional patient complexity and demographics, this finding may be evidence of supply-induced demand, or procedural physicians promoting procedural solutions rather than medical options. This finding could also reflect insufficient procedural physicians to meet demand in certain regions. To fully explore the implications of this finding, future research drawing on patient-level procedural information, including data on procedure urgency and appropriateness, is greatly needed.

This study provides one of the first analyses of the relationships between industry payments and medical device utilization. The observed financial relationships were consistent with prior literature showing that the values of industry payments to cardiologists and orthopedic surgeons are large, with median payments in 2019 of $725 for cardiologists and $509 for orthopedic surgeons, but highly variable with the top quartile of recipients in both groups receiving over $2000 in yearly payments36,37. Numerous prior studies have documented consistent associations between marketing payments and increased prescribing of marketed drugs across classes38, at individual13 and regional levels12. Additionally, one recent study found that patients were more likely to receive an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator made by the manufacturer that provided the largest payments to the operating physician; however, this study did not examine overall device utilization21. Our study is also consistent with a recent analysis of cardiologists which found that receipt of industry for antiplatelet drugs was associated with a small increase in rates of PCI use39.

The relationships between marketing payments and procedural utilization were more consistent for knee arthroplasty than for PCI, which may be due to the fact that knee arthroplasties are largely elective. PCIs may be performed emergently, for acute coronary syndromes, or electively for stable angina. A multi-state study of trends in the rates of PCI from 2010 to 2017 found that 57% of PCIs were elective40. Furthermore, there are national guidelines outlining PCI indications which may lower the chance of individual decision-making41,42. In contrast, knee arthroplasties are nearly always elective and thus may be subject to more individual physician discretion than PCI. Furthermore, CMS’ Local Coverage Determination for PCIs states that PCI is not indicated for patients who can be managed medically whereas the indications for knee arthroplasties are more broad43,44. Previous studies have mainly focused on gift-related payments12,15. The fact that our study finds a differential effect of service payments is interesting because they include consulting which can reflect legitimate financial relationships focused on product development. However, they can also represent hidden marketing relationships45.

In conjunction with prior literature, our findings suggest that more discretionary medical decisions, such as choice of pharmaceutical or device brand or recommending an elective procedure, may be more likely to be influenced by industry marketing payments. Our study is not able to distinguish overuse from appropriate use and does not indicate that payments by medical device manufacturers lead to overuse of knee arthroplasty, as when appropriately used these procedures can provide important functional and symptomatic benefits for patients. However, invasive procedures pose both a high cost to the health system and important perioperative risks to patients, and consistent with practice guidelines should be reserved for patients who do not respond to more conservative therapies. Our findings indicate that supply-side factors, which may drive overuse of these procedures, warrant continued scrutiny from CMS and other payers. Restriction of gift-type marketing payments has been advised by the Institute of Medicine since 200946 and would be one step toward reducing the risk of undue industry influence. Monitoring regions and individual clinicians with high observed to expected ratios of elective procedures, as has been proposed for knee arthroplasties47, and strengthening local coverage determinations are other potential strategies to curtail overuse.

This study is subject to several limitations. First, we studied procedures performed on Medicare FFS beneficiaries, and while older adults account for the majority of individuals in the USA receiving coronary stents and joint replacements, industry payments may have differential effects on care for patients with other insurance, including Medicare Advantage. We speculate that the direction of observed associations would be similar in the private insurance population given that physicians practice in a fee-for-service incentive structure for both Medicare and private insurance and that industry payments are not payer-specific. Physician supply could be a larger driver given that private insurers’ payments for procedures are typically much larger than Medicare payments48, though this may also be counterbalanced by payer controls such as prior authorizations. Second, as a cross-sectional analysis, we are unable to establish causality. Third, the utilization data available excludes reporting on physicians performing fewer than 11 procedures per year; thus, our findings do not generalize physicians with low volume in Medicare FFS. Fourth, while examining HRR-level outcomes allowed us to evaluate the regional association of payments and prescribing, which may account for the broader impact of speaking-related payments, we are unable to make individual-level inferences. Finally, we were not able to distinguish between PCIs which were done emergently versus those done electively.

Conclusion

Among Medicare FFS beneficiaries, regional supply of procedural physicians was associated with greater use of both knee arthroplasty and PCI. Medical device–related gift payments were associated with increased rates of both PCI and knee arthroplasty. Medical device–related total and service payments were associated with increased rates of knee arthroplasty but not PCI. To ensure optimal use of high-cost invasive procedures, payers and policy makers should consider measures that discourage supply-side factors that may lead to overuse while maintaining an adequate supply of procedural physicians to avoid shortages. The data that support the findings of this study are openly available. URLs are cited in references 23–25, 30–33 and 34. The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials.

Supplementary Information

(PDF 160 kb)

Author contributions

There were no non-author contributors to this work.

Funding

This project was supported by grant K76AG074878 from the National Institute on Aging (Dr. Anderson).

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest

Disclaimer

The National Institute on Aging had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Prior presentations: None.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Finkelstein A, Gentzkow M,Williams H. Sources of Geographic Variation in Health Care: Evidence from Patient Migration. Q J Econ. 2016:1681–1726. 10.1093/qje/qjw023.Advance [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Song Y, Skinner J, Bynum J, Sutherland J, Wennberg JE, Fisher ES. Regional Variations in Diagnostic Practices. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):45–53. doi: 10.1056/nejmsa0910881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wennberg DE, Kellett MA, Dickens JD, Malenka DJ, Keilson LM, Keller RB. The association between local diagnostic testing intensity and invasive cardiac procedures. J Am Med Assoc. 1996;275(15):1161–1164. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.15.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin GA, Dudley RA, Lucas FL, Malenka DJ, Vittinghoff E, Redberg RF. Frequency of stress testing to document ischemia prior to elective percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2008;300(15):1765–1773. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.15.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matlock DD, Groeneveld PW, Sidney S, et al. Geographic Variation in Cardiovascular Procedures: Medicare Fee-For-Service versus Medicare Advantage. JAMA. 2013;310(2):155–162. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.7837.Geographic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucas FL, Sirovich BE, Gallagher PM, Siewers AE, Wennberg DE. Variation in cardiologists’ propensity to test and treat is it associated with regional variation in utilization? Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(3):253–260. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.840009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.A Dartmouth Atlas Project Topic Brief. Supply-Sensitive Care. Cent Eval Clin Stud. 2003;(603).

- 8.Goodney PP, Travis LL, Malenka D, et al. Regional variation in carotid artery stenting and endarterectomy in the medicare population. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(1):15–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.864736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinstein JN, Bronner KK, Morgan TS,Wennberg JE. Trends: Trends and geographic variations in major surgery for degenerative diseases of the hip, knee, and spine. Health Aff. 2004;23(SUPPL.):1–9. 10.1377/hlthaff.var.81 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Alter DA, Stukel TA, Newman A. The relationship between physician supply, cardiovascular health service use and cardiac disease burden in Ontario: Supply-need mismatch. Can J Cardiol. 2008;24(3):187–193. doi: 10.1016/S0828-282X(08)70582-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wennberg D, Dickens JJ, Soule D, et al. The relationship between the supply of cardiac catheterization laboratories, cardiologists and the use of invasive cardiac procedures in Northern New England. J Heal Serv Res Policy. 1997;2(2):75–80. doi: 10.1177/135581969700200204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleischman W, Agrawal S, King M, et al. Association between payments from manufacturers of pharmaceuticals to physicians and regional prescribing: cross sectional ecological study. BMJ. 2016;354. 10.1136/bmj.i4189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Wazana A. Is a Gift Ever Just a Gift? Psychiatry Interpers Biol Process. 2000;283(3):373–380. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma M, Vadhariya A, Johnson ML, Marcum ZA, Holmes HM. Association between industry payments and prescribing costly medications: An observational study using open payments and medicare part D data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3043-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeJong C, Aguilar T, Tseng CW, Lin GA, Boscardin WJ, Dudley RA. Pharmaceutical industry-sponsored meals and physician prescribing patterns for medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1114–1122. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nusrat S, Syed T, Nusrat S, Chen S, Chen WJ, Bielefeldt K. Assessment of Pharmaceutical Company and Device Manufacturer Payments to Gastroenterologists and Their Participation in Clinical Practice Guideline Panels. JAMA Netw open. 2018;1(8). 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Samuel AM, Webb ML, Lukasiewicz AM, et al. Orthopaedic Surgeons Receive the Most Industry Payments to Physicians but Large Disparities are Seen in Sunshine Act Data. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(10):3297–3306. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4413-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue K, Blumenthal DM, Elashoff D, Tsugawa Y. Association between physician characteristics and payments from industry in 2015–2017: Observational study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):1–12. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Annapureddy A, Murugiah K, Minges KE, Chui PW, Desai N, Curtis JP. Industry Payments to Cardiologists. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(12):e005016. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005016 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Bergman A, Grennan M, Swanson A. Medical device firm payments to physicians exceed what drug companies pay physicians, target surgical specialists. Health Aff. 2021;40(4):603–612. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Annapureddy AR, Henien S, Wang Y, et al. Association between Industry Payments to Physicians and Device Selection in ICD Implantation. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020;324(17):1755–1764. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyu H, Xu T, Brotman D, et al. Overtreatment in the United States. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Open Payments. https://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/Data/Dataset-Downloads. Published 2018. Accessed December 6, 2020.

- 24.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Physician & Other Practitioners - by Provider. https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-physician-other-practitioners/medicare-physician-other-practitioners-by-provider. Published 2018. Accessed September 11, 2022.

- 25.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Geographic Variation by National, State & County. https://data.cms.gov/summary-statistics-on-use-and-payments/medicare-geographic-comparisons/medicare-geographic-variation-by-national-state-county. Published 2018. Accessed September 11, 2022.

- 26.Annapureddy A, Sengodan P, Mahajan S, et al. Distribution of Industry Payments among Medical Directors of Catheterization and Electrophysiology Laboratories from the Top 100 US Hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(9):1282–1284. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.8775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moynihan R. Key opinion leaders: Independent experts or drug representatives in disguise? Bmj. 2008;336(7658):1402–1403. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39575.675787.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson TS, Dave S, Good CB, Gellad WF. Academic medical center leadership on pharmaceutical company boards of directors. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311(13):1353–1355. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson TS, Gellad WF, Good CB. Characteristics of biomedical industry payments to teaching hospitals. Health Aff. 2020;39(9):1583–1591. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid. Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data: Physician and Other Supplier. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Physician-and-Other-Supplier. Published 2018. Accessed April 28, 2021.

- 31.Supplemental Research Data: Crosswalks. The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice. https://atlasdata.dartmouth.edu/downloads/supplemental#crosswalks. Published 2015. Accessed October 4, 2020.

- 32.Food and Drug Administration. Product Code Classification Database. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/classify-your-medical-device/product-code-classification-database. Published 2020. Accessed December 6, 2020.

- 33.National Institute of Health. Access GUDID. https://accessgudid.nlm.nih.gov/download. Accessed December 6, 2020.

- 34.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Public Use File. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Geographic-Variation/GV_PUF. Published 2018. Accessed December 6, 2020.

- 35.Matlock DD, Groeneveld PW, Sidney S, et al. Geographic variation in cardiovascular procedure use among medicare fee-for-service vs medicare advantage beneficiaries. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2013;310(2):155–162. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.7837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murayama A, Kamamoto S, Shigeta H, Ozak A. Industry payments during the COVID-19 pandemic for cardiologists in the United States. CJC Open. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.cjco.2023.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braithwaite J, Frane N, Partan MJ, et al. Review of Industry Payments to General Orthopaedic Surgeons Reported by the Open Payments Database: 2014 to 2019. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2021;5(5):1–10. doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-21-00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mitchell AP, Trivedi NU, Gennarelli RL, et al. Are Financial Payments From the Pharmaceutical Industry Associated With Physician Prescribing? : A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(3):353–361. doi: 10.7326/M20-5665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yanagisawa M, Blumenthal DM, Kato H, Inoue K, Tsugawa Y. Associations Between Industry Payments to Physicians for Antiplatelet Drugs and Utilization of Cardiac Procedures and Stents. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(7):1626–1633. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06980-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Almarzooq ZI, Wadhera RK, Xu J, Yeh RW. Population Trends in Rates of Percutaneous Coronary Interventions, 2010 to 2017. JAMA Cardiol. 2021. 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.2639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.S. LJ, E. T-HJ, Sripal B, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(2):e21-e129. 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Executive Summary. Circulation. 2011;124(23):2574–2609. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823a5596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Local Coverage Determination: Percutaneous Coronary Interventions. 10.1007/978-1-907673-10-8_7

- 44.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Local Coverage Determination: Major Joint Replacement (Hip and Knee).

- 45.Department of Health and Human Services. Special Fraud Alert: Speaker Programs. Washington DC; 2021. https://oig.hhs.gov/documents/special-fraud-alerts/865/SpecialFraudAlertSpeakerPrograms.pdf.

- 46.Institutute of Medicine. Conflict of Interest in Medical Research, Education, and Practice. Washington DC; 2009. 10.17226/12598

- 47.Ward MM,Dasgupta A. Regional Variation in Rates of Total Knee Arthroplasty Among Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Netw open. 2020;3(4):e203717. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Lopez E, Neuman T, Jacobson G, Levitt L. How much more than Medicare do private insurers pay? A review of the literature. Kaiser Fam Found Medicare. 2020:1-63. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/how-much-more-than-medicare-do-private-insurers-pay-a-review-of-the-literature/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 160 kb)