Abstract

Females increase aggression for mating opportunities and for acquiring reproductive resources. Although the close relationship between female aggression and mating status is widely appreciated, whether and how female aggression is regulated by mating-related cues remains poorly understood. Here we report an interesting observation that Drosophila virgin females initiate high-frequency attacks toward mated females. We identify 11-cis-vaccenyl acetate (cVA), a male-derived pheromone transferred to females during mating, which promotes virgin female aggression. We subsequently reveal a cVA-responsive neural circuit consisting of four orders of neurons, including Or67d, DA1, aSP-g, and pC1 neurons, that mediate cVA-induced virgin female aggression. We also determine that aSP-g neurons release acetylcholine (ACh) to excite pC1 neurons via the nicotinic ACh receptor nAChRα7. Together, beyond revealing cVA as a mating-related inducer of virgin female aggression, our results identify a neural circuit linking the chemosensory perception of mating-related cues to aggressive behavior in Drosophila females.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12264-023-01050-9.

Keywords: Drosophila, Aggression, Pheromone, 11-cis-vaccenyl acetate, Acetylcholine, Neural circuit

Introduction

An outstanding perspective is that evolutionary selection on females may arise from competition for mating opportunities and resources. Female competition is beneficial for reproductive success and offspring quality [1, 2]. The fitness consequences of female competition become obvious over a long time scale and potentially span several generations [3].

Drosophila melanogaster is an ideal model for understanding the neural mechanisms underlying female aggression and provides powerful genetic tools to manipulate neuronal activity [4]. When paired with food, female flies show unique aggressive patterns, including high-posture fencing, head butts, shoves, elevated wings, and charging [5]. Female aggression is controlled by genes of the sex determination hierarchy in flies, including transformer (tra), fruitless (fru), and doublesex (dsx) [6–8], and by sexually dimorphic neurons, such as pC1 and aIP-g [9–12]. In addition to the sex-specific regulators, neuromodulators, including octopamine and drosulfakinin, modulate aggression in both sexes [13, 14]. Female aggression is regulated by social and environmental factors, such as social isolation and limited survival resources [15–17]. Although the close association between female aggression and mating is widely accepted, whether and how female aggression is regulated by mating-related cues remains poorly understood.

Aggressive behavior is strongly influenced by chemosensory inputs [18–20]. 11-cis-vaccenyl acetate (cVA) is a male-specific pheromone synthesized in the male ejaculatory bulb [21, 22], and is transferred to females during mating [23]. cVA is sensed by Or67d and Or65a olfactory receptors [24, 25] and critically regulates male aggression [18, 26]. In females, cVA acts as an aphrodisiac to increase sexual receptivity through the Or67d receptor [21, 27]. Whether female aggression is influenced by cVA remains unclear.

In this study, we show that virgin females become more aggressive when paired with mated females than with virgin females. We demonstrate that cVA, which is carried by mated females, induces virgin female aggression. We further determine a cVA-responsive neural circuit controlling virgin female aggression. Together, our results reveal male-derived cVA as a mating-related trigger of female aggression and identify a neural circuit linking cVA perception to female aggression.

Materials and Methods

Fly Culture and Strains

Flies were reared on standard food containing corn, yeast, and agar at 25 °C and 60% humidity in a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle. To control the density of experimental flies, each cross was set up with 5–6 virgin females and 2–3 males and was transferred every three days. Virgin females were collected 8 h after eclosion and reared in isolation (one fly per vial) or in groups (12 single-sex flies per vial). Flies were transferred to fresh food vials one day before a behavioral test. Behavioral experiments were carried out for 3 h with the lights on. The following strains were obtained from Yi Rao’s lab (Peking University, Beijing, China): Canton-S [28], △nAChR-a7 [29], UAS-Or67d [26], and UAS-dTrpA1 [30]. LexAop2-Shits1 was a gift from Yufeng Pan’s lab (Southeast University, Nanjing, China). Or67dGAL4 [27], UAS>stop>GFP, LexAop2-myr::tdTomato, UAS>stop>Chrimson and LexAop2-FLP [31, 32], dsxGAL4 [33], LexAop2-GCaMP6s [34], UAS>stop>TNTin and UAS>stop>TNT [35], JK1029-VP16-AD, Cha-Gal4-DBD [36], and pC1-SS2 [37] were from Janelia Farm Research Campus. The following strains were from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center: Or65a-GAL4 (BL#9994), UAS-Kir2.1 (BL#6596), Mz19-GAL4 (BL#34497), fruFLP (BL#66870), TRIC (BL#61679), UAS-mCD8-GFP (BL#5137), UAS>stop>Kir2.1(BL#67686), UAS-sytGFP (BL#6925), UAS-Denmark (BL#33062), UAS-shits (BL#44222), UAS>stop>dTrpA1 (BL#66871), SP0 (BL#77892), tudor (BL#1786), R41A01-LexA (BL#54787), and R71G01-LexA (BL#54733). All RNAi lines were from Tsinghua Fly Center. All Drosophila strains in this study will be available on request.

Behavioral Assays

In general, aggressive behavioral assays were applied in an incubator maintained at 25 °C and 60% humidity. The aggressive behavioral chamber was as previously reported [13]. Briefly, the chamber was composed of four layers of transparent acrylic plates (diameter: 15 mm; the height of each plate: 3 mm). The bottom plate contained a food substrate (diameter: 8 mm; depth: 3 mm). Aggressive behavioral assays were applied on the 6th or 7th day after eclosion. Tested flies were anesthetized by ice, and introduced into the chamber, and a transparent film was used to separate them from each other. After recovering for 1 h, the transparent film was removed and aggressive behavior was recorded by a camera (Canon VIXIA HF R500) for 15 min at a frame rate of 4 Hz. Aggressive patterns were scored during this 15-min period. The definition of a female aggressive pattern head-butt was thrusting the torso towards the opponent and striking the opponent with the head [5]. The latency to attack was defined as the difference in the time between the first encounter (social interaction lasting at least ∼2 s) and the occurrence of the first head-butt. All aggression assays were analyzed manually and randomly assigned to three experimenters for independent scoring. The scorers were blind to the genotypes and conditions of the experiment.

For dTrpA1 activation and Shits1 inactivation assays, flies were collected within 8 h post-eclosion and reared in isolation at 20 °C. Aggressive behavioral assays were applied at 20 °C (control) or 30 °C (activation or inactivation) and 60% humidity. For assays at 30 °C, females were pre-warmed at 30 °C for 20 min before recording.

Virgin vs Mated Assays

Female flies were collected within 8 h after eclosion and reared under single-housed conditions. Their thoraxes were painted with two different colors of acrylic paint two days after eclosion. Some virgin females finished successful copulation during the time intervals 1 h, 24 h, 48 h, or 72 h before the aggressive behavioral assays, and then were separated from males. Virgin and mated females were transferred to fresh vials containing standard food on the 5th day post-eclosion. Aggressive behavior was recorded the next day.

In the experiments with decapitated females, both virgin and mated females were decapitated under anesthesia and then introduced into the behavioral chamber before introducing two tested virgin flies.

In the experiments involving females with severed antennae, antennae were disrupted bilaterally under anesthesia 2 days before behavioral assay.

To obtain mated females without sperm or sex peptide, we selected the male offspring produced by homozygous tudor females that copulated with Canton-S males as sperm-less males and the males with a non-functional SP gene [38] as sex-peptide-less males to copulate with Canton-S females.

The time that females spent in the food area were quantified as the sum of time for which over half of the virgin female body was in the food area.

Application of cVA Assay

Canton-S females were collected within 8 h post-eclosion and reared under single-housed conditions. The method of application of synthetic cVA was similar to that described previously [18]. Different concentrations of synthetic cVA (Cayman Chemicals, USA) dissolved in ethanol (or ethanol alone as a control) were provided on a piece of filter paper placed in the behavioral chamber. Two virgin females were introduced to the behavioral chamber and separated by a transparent film under ice anesthesia. Aggressive behavior was recorded after 1 h of recovery.

In locomotion assays, flies were separately introduced into chambers containing a filter paper which was socked with different concentrations of synthetic cVA or solvent. The total walking distance of individuals was recorded for 5 min and analyzed by Ctrax software [39].

For the group-housed assay, Canton-S females were collected within 8 h post-eclosion and reared in a group (12 single-sex flies per vial). 50 µg cVA or solvent was provided on a piece of filter paper in the behavioral chamber. Two group-housed female flies were introduced to one behavioral chamber under ice anesthesia and aggressive behavior was recorded after 1 h of recovery.

For chronic exposure assay, Canton-S females were collected within 8 h post-eclosion and reared under single-housed conditions. Virgin females were transferred to vials containing a filter paper socked with 50 µg cVA or solvent 24 h before a behavioral test. Two females were introduced into one behavioral chamber without application of cVA or solvent and aggressive behavior was recorded after 1 h recovering.

For the absence of food assay, Canton-S females were collected within 8 h post-eclosion and reared in a single-housed condition. 50 µg cVA or solvent was provided on a piece of filter paper in the behavioral chamber. Two females were introduced into the behavioral chamber which contained an agarose plate and aggressive behavior was recorded after 1 h recovering.

Gas Chromatography (GC) MS Analysis

The quantification method was adapted from earlier reports [40, 41]. Hexane extracts were prepared by immersing 20 flies in hexane (Aldrich) for 4 h at room temperature. Hexane extracts were then reconstituted in 100 µL of hexane containing 100 ng/µL dodecane (nC12) as an injection standard. A 2 µL sample of the extract was then injected into an Agilent 7,890 gas chromatograph fitted with an HP-5MS fused silica capillary column (0.25 mm × 30 m, 0.25 µm film thickness) linked to a mass analyzer (Agilent 7000C). The injector was held at 280 °C and operated in the splitless mode for 1 min after injection. The helium flow was set at 1 mL/min. Analysis of the extract was carried out with a column temperature profile that began at 50 °C (held for 1.5 min), ramped at 10 °C per min to 150 °C, and then 4 °C per min to 280 °C where it was held for 5 min. Experiments were repeated 6 times per treatment. MassHunter qualitative and quantitative analysis software (Agilent Technologies) was used to quantify compounds based on peak areas relative to internal standard C12.

Immunohistochemistry

Brains of adult female flies were dissected under cold anesthesia in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Corning, 21-040- CVR). Brains were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hangzhou, China) for 55 min and washed three times for 20 min in PBT (1× PBS containing 0.3% Triton-X100) at room temperature. Brains were then blocked in PBT containing 5% goat serum (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at room temperature and were incubated with primary antibodies for 18–24 h at 4 °C. Next, the brains were washed three times in PBT for 20 min before being incubated in the secondary antibodies for 18–24 h at 4 °C. The brains were washed three times for 20 min in PBT at room temperature and were fixed in 4% PFA for 4 h at room temperature. After fixation, the brains were washed three times in PBT for 20 min at room temperature. Lastly, the brains were mounted onto poly-L-lysine (PLL)-coated coverslips in 1× PBS (Sigma-Aldrich). The coverslips with mounted brains were then soaked for 5 min each in a gradient of ethanol baths: 30%, 50%, 75%, 95%, and 100%, and then soaked three times for 5 min in xylene. Dibutylphthalate polystyrene xylene (DPX) (Sigma-Aldrich) was applied to the samples on each coverslip and the coverslips were placed on slides and dried for 2 days before imaging.

Images were taken with a Carl Zeiss (LSM710, Germany) confocal microscope and then processed with Fiji software (https://imagej.net/Fiji). The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-nc82 (1:50; DSHB), chicken anti-GFP (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific), rabbit anti-GFP (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific), mouse anti-GFP-20 (1:100; Sigma), and rabbit anti-DsRed (rabbit polyclonal) (1:1000; Takara Bio). The following secondary antibodies were used: Alexa Fluor goat anti-chicken 488 (1:500), Alexa Fluor goat anti-rabbit 488 (1:500), Alexa Fluor goat anti-mouse 546 (1:500), Alexa Fluor goat anti-mouse 488 (1:500), and Alexa Fluor goat anti-rabbit 546 (1:500) all from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Transcriptional Reporter of Intracellular Calcium (TRIC)

Adult fly brains were dissected and stained using the procedure described in the Immunohistochemistry section. The chicken anti-GFP and rabbit anti-DsRed primary antibodies and anti-chicken-488 and anti-rabbit-546 secondary antibodies were used to stain GFP and RFP, respectively. The mean intensities of GFP and RFP signals were measured using ImageJ (Fiji), and the relative TRIC signal was calculated as the GFP signal divided by the RFP signal.

Brain Registration

The protocol was adapted from previous reports [42, 43]. Briefly, a standard brain was created in CMTK software by averaging six male and female brains stained with nc82 [44, 45]. The registration of confocal stacks was done by linear registration and non-rigid warping based on the nc82 channel [46].

Calcium Imaging

Adult flies were reared on food containing 0.4 mmol/L all-trans-retinal (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) and kept in the dark for 5–6 days. Flies were reared on normal food as the control group. Female flies expressing Chrimson in aSP-g neurons and GCaMP6s in pC1 neurons were briefly anesthetized on ice and their brains were dissected in saline (in mmol/L: 103 NaCl, 3 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 1.5 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 1 NaH2PO4, 5 N-tri-(hydroxymethyl)-methyl-2-aminoethane-sulfonic acid, 20 D-glucose, 17 sucrose, and 8 trehalose) under low light to avoid spurious activation. Brains were immersed in saline during imaging. The lateral protocerebrum complex (LPC) projection of pC1 neurons was identified with GCaMP6s fluorescence excited at 920 nm. Chrimson was excited with red light (620 nm, 0.03 mW/mm2; Kemai Vision Technology, Dongguan, China). Brain images were acquired on a Nikon A1R+ confocal microscope (Japan) with a 40× water immersion objective. A 256 × 256-pixel imaging region was captured at a rate of 2 frames per second. The images were analyzed with a graphical user interface written in MatLab [42]. Regions of interest were selected manually. In pharmacology experiments, 1 mmol/L MECA (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was applied 10 min before optogenetic stimulation [47]. F0 was defined as the mean F from the first 10 s of baseline recording. ΔF/F was compared between the signal at 1 s before stimulation with the signal at 1 s after stimulation onset.

Connectomics Analysis

Synaptic connections between aSP-g neurons and pC1 neurons were identified by the recently generated full adult female brain electron microscopic (EM) image set [48]. We obtained the number of synaptic connections and the unique identifier (Cell ID) from the following website: https://neuprint.janelia.org.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism9 (GraphPad software) or MatLab (MathWorks) software. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test was used in quantitative comparisons. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used for comparisons among multiple groups, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons. Mann-Whitney U-tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used for between- and within-group comparisons, respectively. For the comparison of attacking first, the χ2 test was applied. The sample sizes are indicated in the figures.

Results

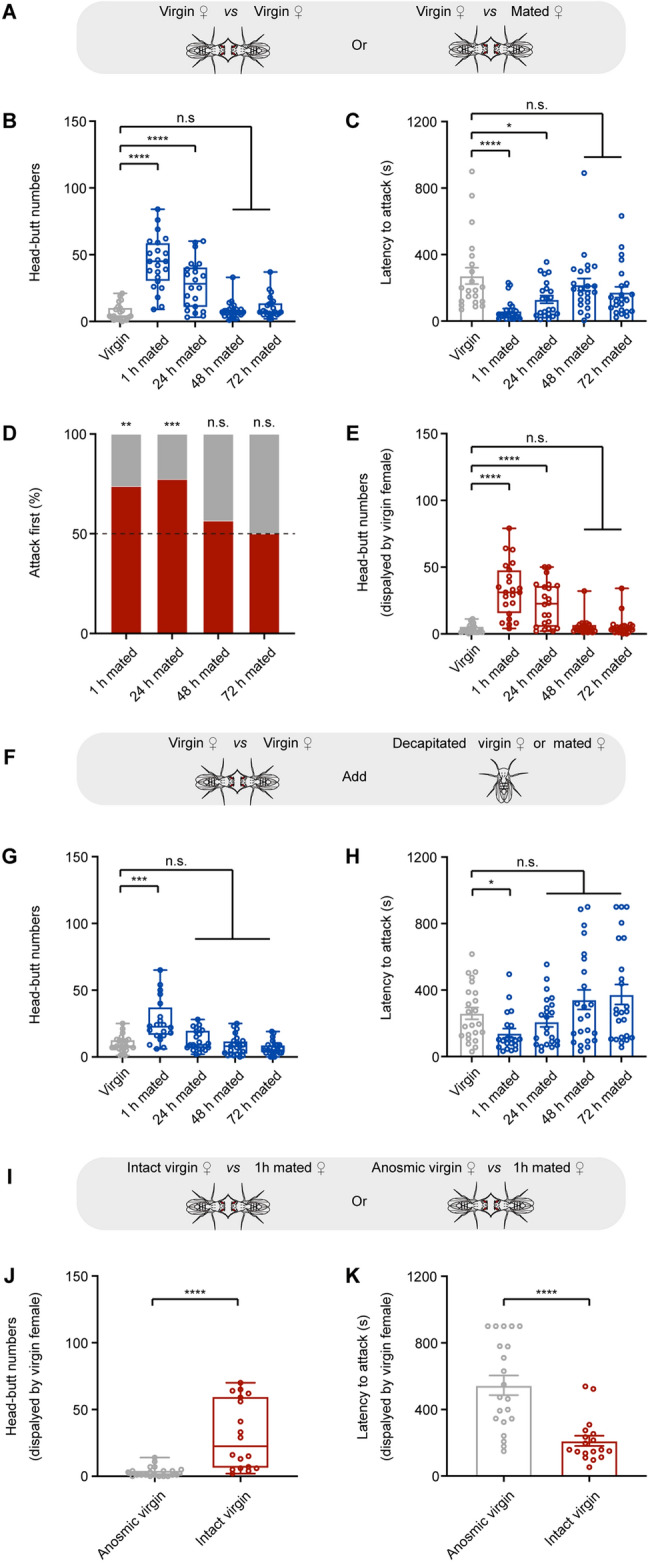

Mated Females Elicit Virgin Female Aggression

To determine whether mating experience affects female aggression, we paired two virgin females or one virgin female with one mated female at different time points post-mating (hereafter referred to as ‘~ h mated females’) in the aggressive behavioral chamber (Fig. 1A). Behavioral analysis showed that the pairs, including ‘virgin vs 1 h mated’ or ‘virgin vs 24 h mated’, showed increased aggression as demonstrated by increased head-butt numbers (Fig. 1B) and reduced latency to attack (Fig. 1C). Further analysis showed that virgin females initiated more attacks (Fig. 1D) and increased head-butt numbers (Fig. 1E) against 1 h or 24 h mated females. Moreover, we analyzed the time virgin females spent on the food plate and found that they spent significantly longer time on the plate when paired with 1 h or 24 h mated females than with virgin females (Fig. S1A–C). Therefore, virgin females become more aggressive when paired with 1 h or 24 h mated females.

Fig. 1.

Volatile signals from mated females induce virgin female aggression. A Experimental schematic. A virgin female is paired with another virgin female or a mated female. B, C Head-butt numbers and latency by a pair of female flies. D Percentages of initiating an attack by virgin females (gray bars) and mated females (red bars). E Head-butt numbers by virgin females (n = 21–23). F Experimental schematic. Two virgin females are paired together and are exposed to a decapitated virgin female or a decapitated mated female. G, H Head-butt numbers and latency by a pair of female flies (n = 20–24). I Experimental schematic. A 1 h mated female is paired with an intact or anosmic virgin female. J, K Head-butt numbers and latency by virgin female flies (n = 18–21). *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001, ****P <0.0001, otherwise no significant difference (Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple-comparison post hoc test for B, C, E, G, and H; Mann-Whitney U test for J and K; χ2 test for D). Error bars, ± SEM.

Mated female aggression is promoted by the receipt of sex peptides and sperm during copulation [49]. To examine whether the aggressivity of mated females influences virgin female aggression, we paired one virgin female with one 1 h mated female without sex peptide or sperm (Fig. S2A). Behavioral analysis suggested that the pairs showed increased aggression (Fig. S2B, C). Consistent with previous studies [49], mated females without sex peptide or sperm did not show high attacks (Fig. S2D). In contrast, virgin females showed increased aggression (Fig. S2E, F). Virgin females also spent more time on the food plate when they were paired with 1 h mated females without sperm or sex peptide than with virgin females (Fig. S2G). Therefore, the aggressivity of mated females does not influence virgin female aggression.

Males transfer chemicals to mate females during copulation [23]. We then investigated whether the increased virgin female aggression is the result of chemosensory cues from mated females. We paired two virgin females together and added a decapitated virgin or mated female into the aggressive behavioral chamber (Fig. 1F). Aggression between two virgin females increased when a decapitated 1 h mated female was added but did not increase when a decapitated virgin or 24–72 h mated female was added (Fig. 1G, H). This is consistent with the above results that virgin female aggression greatly decreased when paired with mated females with a prior mating experience longer than 24 h (Fig. 1B–E). These results together indicate that the mating-related inducer of virgin female aggression is short-lived.

To determine whether volatile olfactory cues from mated females elicit virgin female aggression, we impaired the olfactory sensation of a virgin female by disrupting the antenna and then paired it with a 1 h mated female (Fig. 1I). Compared with intact virgin females, anosmic virgin females showed decreased aggression toward 1 h mated females (Fig. 1J, K) and spent less time on the food plate (Fig. S1D, E). These results suggest that virgin female aggression is promoted by volatile olfactory inducers from mated females.

Mating-related cVA Promotes Virgin Female Aggression

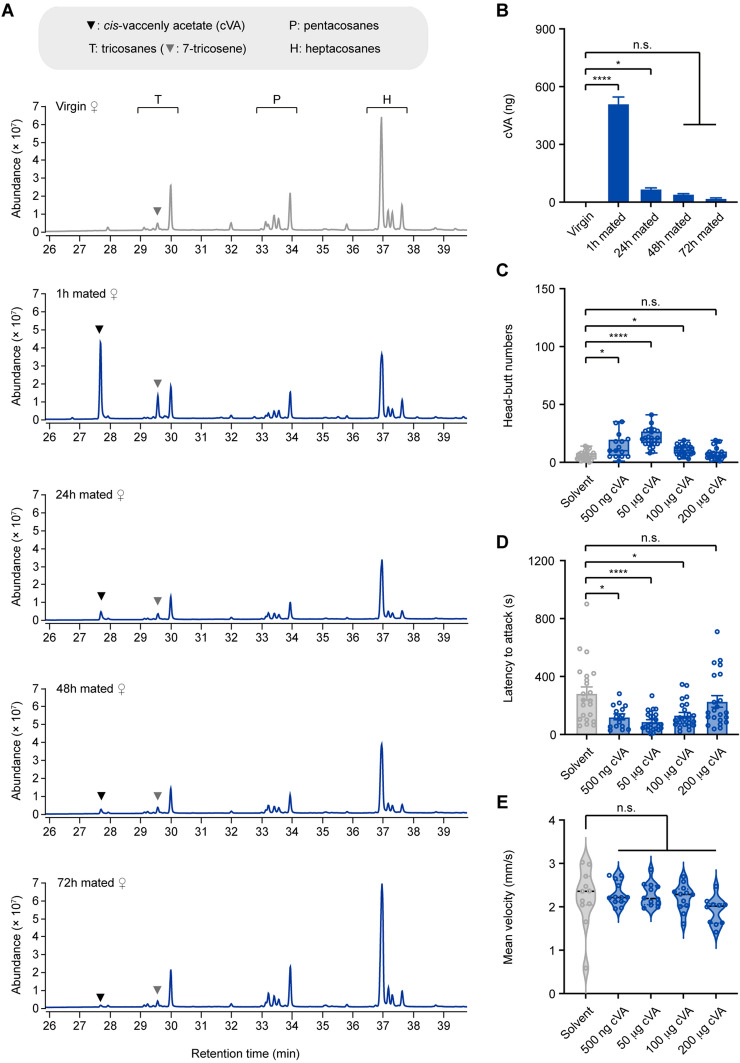

We next addressed the identity of the olfactory cues. We compared the chemical profiles of virgin and 1–72 h mated females using gas chromatography-flame ionization detection and mass spectrometry (Table S1). Two pheromones, cVA, and 7-tricosene (7-T) were significantly increased in 1 h mated females (Fig. 2A). cVA is a male-specific volatile pheromone transferred to mated females during copulation [41, 50]. 7-T is a male-enriched cuticular hydrocarbon transferred to females via cuticular contact during copulation [51, 52].

Fig. 2.

Male-specific cVA stimulates virgin female aggression. A Hydrocarbon profiles for extracts from virgin, 1 h mated, 24 h mated, 48 h mated, and 72 h mated females. Each profile is from a hexane extract of 20 age-matched virgin or mated females. B Quantification of cVA in extracts of virgin and mated female single flies (n = 6). C, D Head-butt numbers and latency by a pair of virgin female flies after application of 500 ng, 50 µg, 100 µg, and 200 µg of cVA or solvent (n = 15–24). E Locomotion of individual virgin females at different concentrations of cVA or solvent (n = 11–12). *P <0.05, ****P <0.0001, otherwise no significant difference (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test for B; Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple-comparison post hoc test for C, D, and E). Error bars, ± SEM.

Quantitation of chemical profiles showed that a 1 h mated female carries ~500 ng cVA (Fig. 2B) and 150 ng 7-T (Fig. S3A). Application of 7-T from 200 ng to 20 µg did not promote virgin female aggression (Fig. S3B, C). In contrast, applying 500 ng cVA, which is almost identical to the amount of cVA carried by a 1 h mated female, significantly increased virgin female aggression (Fig. 2C, D). The aggression-inducing effect of cVA was dose-dependent: it peaked at 50 µg and became almost ineffective at 200 µg (Fig. 2C, D). The locomotion of virgin females was not affected by the application of cVA (Fig. 2E), suggesting that cVA-induced virgin female aggression is not due to enhanced locomotor activity. Therefore, cVA is the major mating-related inducer of virgin female aggression.

Aggression between virgin females is promoted by social isolation or food [15, 17, 53]. We thus investigated whether these factors modulate cVA-induced virgin female aggression. Group-housed virgin females showed increased aggression in response to cVA stimulation (Fig. S4A–C), whereas food deprivation inhibited cVA-induced virgin female aggression (Fig. S4D–F). Therefore, cVA-induced virgin female aggression depends on food but not a social experience.

Male aggression is increased by acute exposure to cVA but is suppressed by chronic exposure to cVA [18, 26]. In contrast, females chronically exposed to cVA still showed increased aggression (Fig. S4G–I), demonstrating the sex-specific response to cVA.

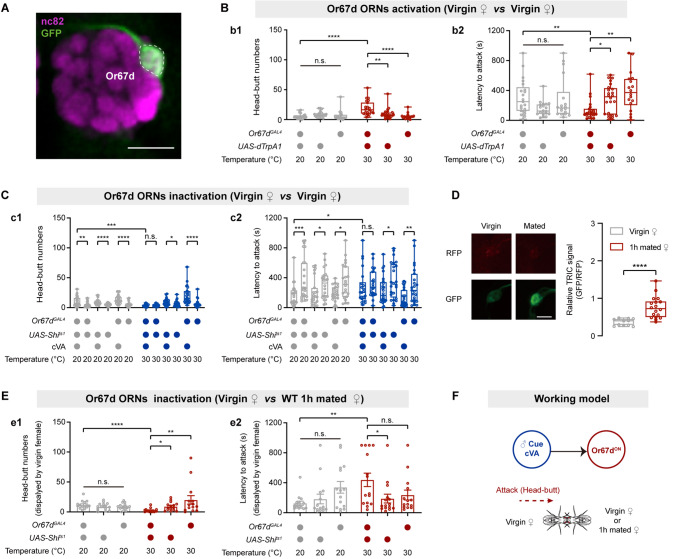

Or67d Mediates Virgin Female Aggression Induced by both Synthetic cVA and cVA Carried by Mated Females

cVA activates both Or67d and Or65a olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs) [24, 27, 54]. We, therefore, examined the roles of Or67d and Or65a ORNs in virgin female aggression. We used the thermosensitive cation channel dTRPA1 [30] to activate neurons labeled by Or67dGAL4 (Fig. 3A) or Or65a-GAL4 (Fig. S5A). Female aggression was enhanced by activating Or67d ORNs (Fig. 3B) but was not affected by activating Or65a ORNs (Fig. S5B). Furthermore, we expressed Shibirets1 (Shits1) [55], which temporally inhibits synaptic transmission via temperature shifting, in Or67d and Or65a ORNs. Silencing Or67d ORNs suppressed cVA-induced female aggression (Fig. 3C). However, silencing Or65a ORNs did not influence cVA-induced female aggression (Fig. S5C). Furthermore, ablation of the Or67d gene completely abolished cVA-induced virgin female aggression, and re-expression of the Or67d gene in the Or67d-null mutant restored cVA-induced virgin female aggression (Fig. S6A). Therefore, the Or67d receptor and Or67d ORNs are essential for cVA-induced virgin female aggression.

Fig. 3.

Or67d ORNs mediate cVA-induced virgin female aggression. A Confocal image of the antennal lobe. Or67d-GAL4 labeled Or67d ORNs in the female brain (green: DA1 glomerulus). nc82, neuropil marker (magenta). Scale bar, 50 µm. B Head-butt numbers (b1) and latency (b2) by virgin females during dTrpA1-mediated thermogenetic activation of Or67d ORNs (n = 18–24). C Head-butt numbers (c1) and latency (c2) by virgin females during Shibirets1-mediated inactivation of Or67d ORNs by application of 50 µg cVA or solvent (n = 22–24). D Right, TRIC signals in Or67d ORNs of virgin females in the presence of mated females or virgin females (n = 11–18). Left, representative TRIC images; red channel, internal control RFP signal; green channel, activity-dependent TRIC signal. Scale bar, 20 µm. E Head-butt numbers (e1) and latency (e2) by virgin females with inactivation of Or67d ORNs toward wild-type 1 h mated females (n = 14–15). F Summary model of cVA activation of Or67d ORNs to promote virgin female aggression. *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001, ****P <0.0001, otherwise no significant difference (Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple-comparison post hoc test for B, C, and E; Mann-Whitney U test for D). Error bars, ± SEM.

We next examined whether Or67d mediates the virgin female aggression induced by cVA carried by mated females. We used TRIC [56], which measures prolonged changes in Ca2+ levels, to assess the activity of Or67d ORNs in virgin females. The TRIC signal in Or67d ORNs significantly increased when virgin females were paired with mated females compared with virgin females (Fig. 3D). Importantly, inactivation of Or67d ORNs or ablation of the Or67d gene abolished the virgin female aggression induced by mated females (Fig. 3E, S6B). Expression of UAS-Or67d under the control of Or67dGAL4 restored virgin female aggression (Fig. S6B). Taken together, these results suggest that the Or67d receptor detects physiological levels of cVA carried by mated females to induce virgin female aggression (Fig. 3F).

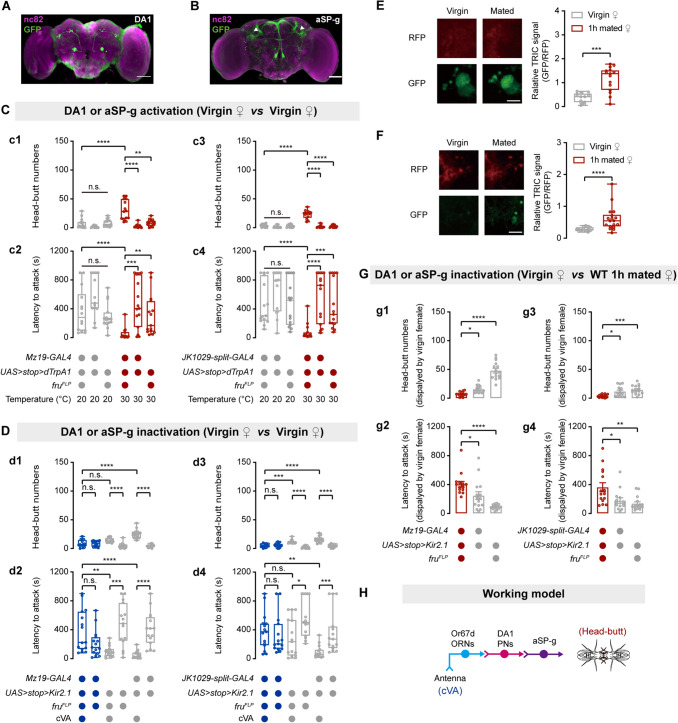

Second- and Third-order cVA-responsive Olfactory Neurons Regulate cVA-induced Virgin Female Aggression

Or67d ORNs innervate the DA1 glomerulus in the antennal lobe [27, 57]. DA1 projection neurons (PNs) innervate aSP-g neurons to transmit cVA information in females [36, 58]. Thus, we investigated whether DA1 PNs and aSP-g neurons regulate virgin female aggression. Given that both DA1 PNs and aSP-g neurons express fru [36, 57–59], we labeled DA1 PNs by combining Mz19-GAL4 [60] and fruFLP and labeled aSP-g neurons by combining JK1029-split-GAL4 [36] and fruFLP (Fig. 4A, B). dTrpA1-mediated activation of DA1 PNs or aSP-g neurons promoted virgin female aggression (Fig. 4C). We next examined whether silencing DA1 PNs or aSP-g neurons suppresses cVA-induced virgin female aggression. We silenced DA1 PNs or aSP-g neurons by expressing the inwardly-rectifying K+ channel Kir2.1 [61]. cVA-induced virgin female aggression was suppressed by the inactivation of DA1 PNs or aSP-g neurons (Fig. 4D). Moreover, significant increases in the TRIC signal were recorded in both DA1 PNs and aSP-g neurons of virgin females that were paired with 1 h mated females (Fig. 4E, F). Kir2.1-mediated inactivation of DA1 PNs or aSP-g neurons also significantly inhibited virgin female aggression induced by mated females (Fig. 4G). Taken together, both DA1 PNs and aSP-g neurons mediate cVA-induced virgin female aggression (Fig. 4H).

Fig. 4.

DA1 PNs and aSP-g neurons physiologically respond to cVA and regulate cVA-induced virgin female aggression. A, B Brains of MZ19-GAL4/UAS-mCD8::GFP; fruFLP and UAS-mCD8::GFP; JK1029-split-GAL4/ fruFLP females stained with anti-GFP antibody (green) and the neuropil marker nc82 (magenta). Projections of aSP-g neurons in LPC are indicated by the white arrowhead. Scale bars, 50 µm. C Head-butt numbers and latency by virgin females during dTrpA1-mediated thermogenetic activation of DA1 PNs (c1, c2) or aSP-g neurons (c3, c4) (n = 13–15). D Head-butt numbers and latency by virgin females during Kir2.1-mediated inactivation of DA1 PNs (d1, d2) or aSP-g neurons (d3, d4) by application of 50 µg cVA or solvent (n = 15). E, F Right, TRIC signals in DA1 PNs or aSP-g neurons of virgin females in the presence of mated females or virgin females (n = 13–18). Left, representative TRIC images; red channel, internal control RFP signal; green channel, activity-dependent TRIC signal. Scale bar, 20 µm. G Head-butt numbers and latency by virgin females with inactivation of DA1 PNs (g1, g2) or aSP-g neurons (g3, g4) toward wild-type 1 h mated females (n = 14–15). H Summary model for cVA-mediated aggression circuit including Or67d ORNs, DA1 PNs, and aSP-g neurons in virgin females. *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001, ****P <0.0001, otherwise no significant difference (Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple-comparison post hoc test for C, D, and G; Mann-Whitney U test for E and F). Error bars, ± SEM.

The cVA-responsive aSP-g neurons are dimorphic in the sexes, which is regulated by fru [36]. We, therefore, masculinized the aSP-g neurons in females by expressing FruM, the protein products of male-specific fru transcripts. This manipulation changed the neuronal morphology of aSP-g neurons in the female brain (Fig. S7A) and inhibited cVA-induced virgin female aggression (Fig. S7B, C), demonstrating that the sex-specific circuitry regulates cVA-induced virgin female aggression.

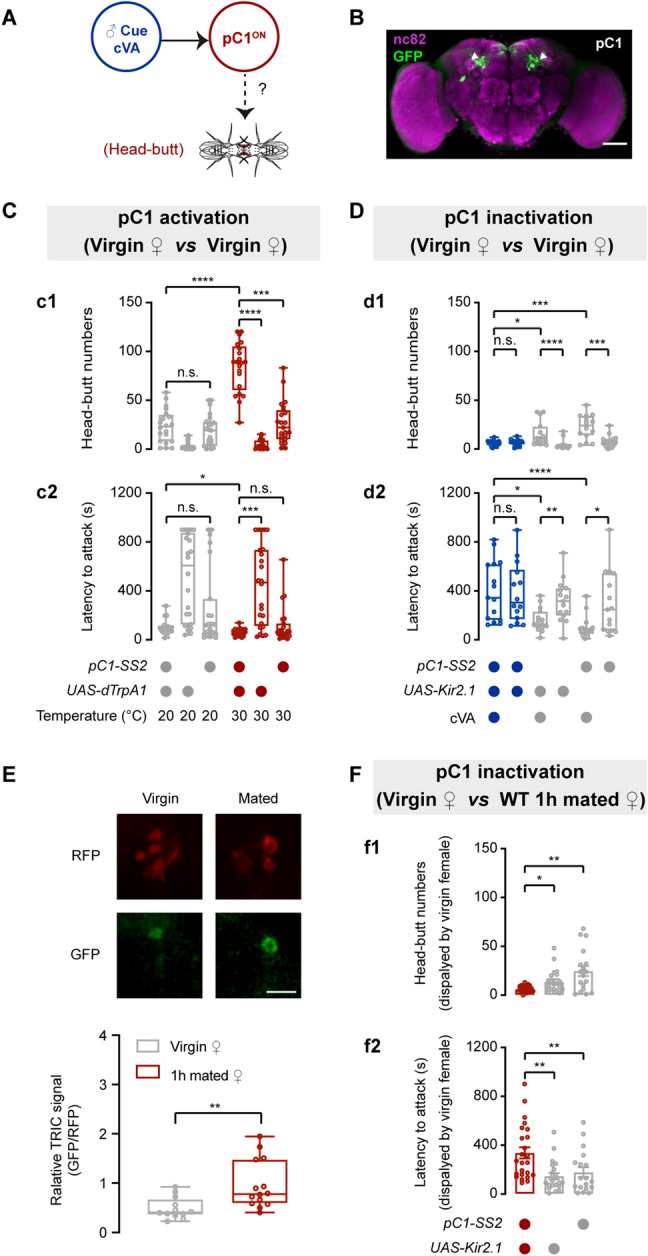

Central pC1 Neurons Mediate the Virgin Female Aggression Promoted by cVA

Two central brain neurons, pC1 and pCd neurons, physiologically respond to cVA and regulate female sexual receptivity [42]. We thus examined whether these neurons participate in cVA-induced female aggression (Fig. 5A). We labeled pC1 neurons by using pC1-SS2 [37] (Fig. 5B) or by combining R71G01-LexA and dsxGAL4 [42]. dTrpA1-mediated activation of pC1 neurons promoted virgin female aggression (Fig. 5C, S8A). However, activation of pCd neurons that were labeled by combining R41G01-LexA and dsxGAL4 [42] did not promote virgin female aggression (Fig. S8B). We next genetically silenced pC1 neurons by expressing Kir2.1 or tetanus toxin light chain (TNT) [62] that inactivates neurons via inhibiting synaptic vesicle release. Silencing pC1 neurons suppressed cVA-induced virgin female aggression (Fig. 5D, S8C). Conversely, silencing pCd neurons by expressing TNT did not affect cVA-induced virgin female aggression (Fig. S8D). Therefore, we conclude that pC1 but not pCd neurons mediate cVA-induced virgin female aggression.

Fig. 5.

pC1 neurons mediate cVA-induced virgin female aggression. A Proposed model shows that cVA activates pC1 neurons to mediate virgin female aggression. B Brain of a pC1-SS2 > UAS-mCD8::GFP female stained with anti-GFP antibody (green) and the neuropil marker nc82 (magenta). Projections of pC1 neurons in the LPC are indicated by the white arrowheads. Scale bar, 50 µm. C Head-butt numbers (c1) and latency (c2) by virgin females during dTrpA1-mediated thermogenetic activation of pC1 neurons (n = 21–24). D Head-butt numbers (d1) and latency (d2) by virgin females during Kir2.1-mediated inactivation of pC1 neurons by application of 50 µg cVA or solvent (n = 14–15). E Lower panel, TRIC signals in pC1 neurons of virgin females in the presence of mated females or virgin females (n = 13–15). Upper panel, representative TRIC images; red channel, internal control RFP signal; green channel, activity-dependent TRIC signal. Scale bar, 20 µm. F Head-butt numbers (f1) and latency (f2) by virgin females with inactivation of pC1 neurons toward wild-type 1 h mated females (n = 18–24). *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001, ****P <0.0001, otherwise no significant difference (Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple-comparison post hoc test for C, D, and F; Mann-Whitney U test for E). Error bars, ± SEM.

In addition, we found that mated females induced a significant increase of the TRIC signal in pC1 neurons of virgin females (Fig. 5E). Kir2.1-mediated inactivation of pC1 neurons significantly inhibited virgin female aggression induced by mated females (Fig. 5F). Therefore, pC1 neurons mediate virgin female aggression towards mated females.

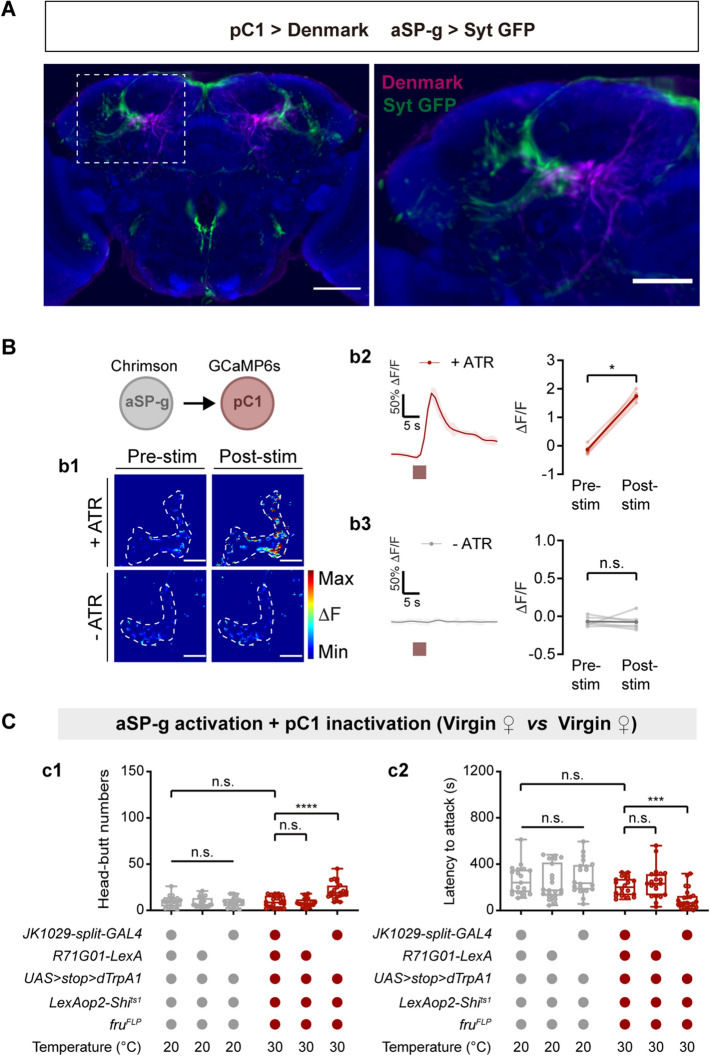

pC1 Neurons Function Downstream of aSP-g Neurons to Regulate the Female Aggression Promoted by cVA

We noted that female aSP-g and pC1 neurons sent projections to the LPC (Fig. 4B, 5B) and responded to cVA (Fig. 4F, 5E). We speculated that pC1 neurons may be a downstream target of aSP-g neurons in the cVA-responsive neural circuit. To test this hypothesis, we first investigated the directionality of cVA information flow by using Syt::GFP and DenMark for pre- and post-synaptic labeling of aSP-g and pC1 neurons [63]. Registration of pre-synaptically labeled aSP-g with post-synaptically labeled pC1 in a standard brain revealed a clear overlap in the LPC region (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, we used the full adult female brain EM image set [48] and found that aSP-g neurons have synaptic input on pC1 neurons (Table S2). These data suggest that pC1 neurons are direct targets of aSP-g neurons.

Fig. 6.

pC1 neurons are functionally downstream targets of aSP-g neurons in virgin female aggression. A Labeling of dendrites and axons in a female brain by expression of the dendritic marker DenMark (magenta) in pC1 neurons and the axonal marker Syt::GFP (green) in aSP-g neurons of a female brain. Co-registration of aSP-g axons (green) and pC1 dendrites (magenta) onto a standard brain (left). The boxed region containing overlaps between aSP-g and pC1 processes is enlarged (right). Scale bars, 50 µm. B Fluorescence images were taken before and after aSP-g activation (b1). Circles: pC1 dendrites in the LPC. Scale bars, 20 µm. Chrimson-mediated aSP-g activation evokes significant Ca2+ signals in pC1 neurons of females reared on food containing ATR (b2), but not in pC1 neurons of females reared on food without ATR (b3). Red boxes, light stimulation. C Shibirets1-mediated inactivation of pC1 neurons suppresses the virgin female aggression induced by activating aSP-g neurons using dTrpA1. c1 Head-butt numbers; c2 latency (n = 19-32). **P <0.01, ***P <0.001, otherwise no significant difference (Wilcoxon signed-rank test for B; Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple-comparison post hoc test for C). Error bars, ± SEM.

Encouraged by these anatomical findings, we next tested whether there is a functional connection between aSP-g and pC1 neurons by Ca2+ imaging. we expressed the red-shifted opsin Chrimson [64] in aSP-g neurons and GCaMP6s [34] in pC1 neurons. The intracellular Ca2+ levels of pC1 neurons increased with light stimulation, while no Ca2+ signals were detected in the absence of all-trans-retinal (ATR) that is required for Chrimson activation in insects (Fig. 6B). Taken together, these data suggest that pC1 neurons receive excitatory input from aSP-g neurons.

We next asked whether pC1 neurons function downstream of aSP-g neurons in virgin female aggression. We applied an epistasis analysis in which aSP-g neurons were activated using dTrpA1, while pC1 neurons were concomitantly silenced using Shits1 in a temperature-dependent manner. At high temperatures, silencing pC1 neurons inhibited the virgin female aggression induced by the activation of aSP-g neurons (Fig. 6C). Thus, pC1 neurons function downstream of aSP-g neurons to promote virgin female aggression.

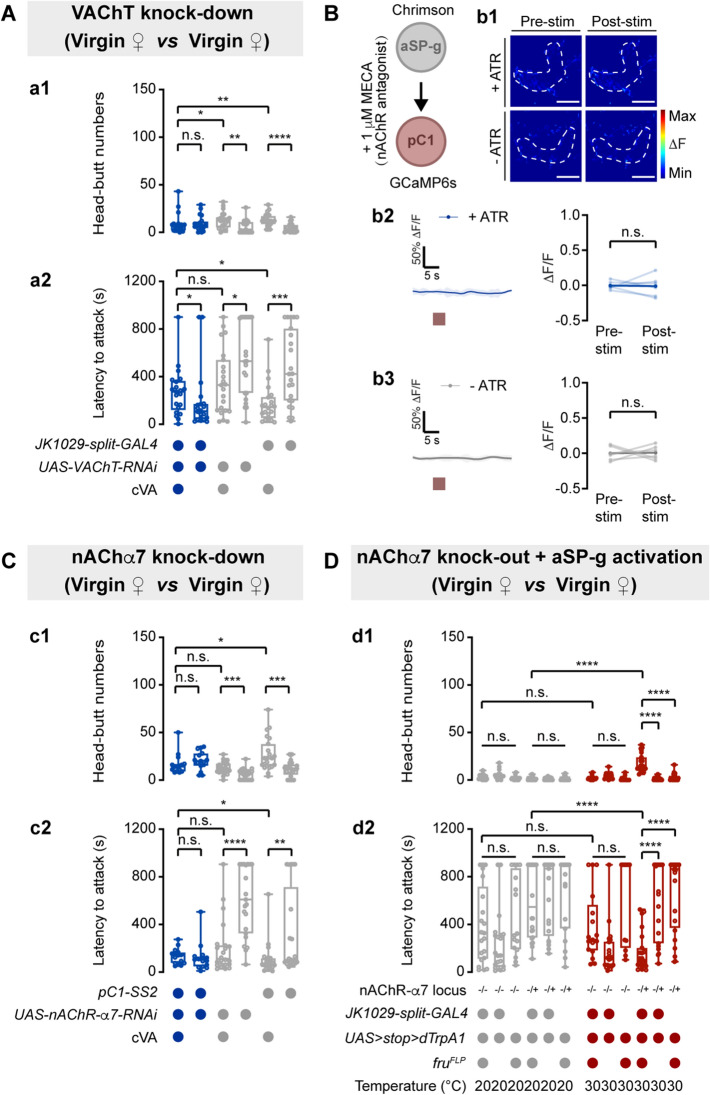

aSP-g Neurons Release ACh to Activate pC1 Neurons to Regulate cVA-induced Virgin Female Aggression

We next investigated which neurotransmitters in aSP-g neurons could regulate virgin female aggression. Given that the driver labeling aSP-g neurons is made by fusing Gal4 to the promoter of choline acetyltransferase [36], we speculated aSP-g neurons may be cholinergic. Indeed, knockdown of the vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT) in aSP-g neurons suppressed cVA-induced virgin female aggression (Fig. 7A), suggesting that aSP-g neurons release ACh to promote virgin female aggression.

Fig. 7.

pC1 neurons receive ACh signaling from aSP-g neurons through nAChR-α7 to control virgin female aggression. A Head-butt numbers (a1) and latency (a2) by virgin females with RNAi-mediated VAChT knockdown in aSP-g neurons by application of 50 µg cVA or solvent (n = 20–23). Genotypes and cVA applications are indicated below the plot. B Representative images during aSP-g > Chrimson pre-stimulation and post-stimulation of GCaMP6s response in pC1 neurons with MECA application (b1). Circles: pC1 dendrites in the LPC. Scale bars, 20 µm. Application of MECA blocks Ca2+ signals evoked by aSP-g activation in pC1 neurons (b2, b3). Red boxes: light stimulation. C Knocking down the expression of nAChR-α7 in pC1 neurons suppresses cVA-induced female aggression. (c1) Head-butt numbers; (c2) latency (n = 21–28). D Aggression is not promoted by activating aSP-g neurons in nAChR-α7 mutant female flies. (d1) Head-butt numbers; (d2) latency (n = 21–24). *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P <0.001, ****P <0.0001, otherwise no significant difference (Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple-comparison post hoc test for A, C, and D; Wilcoxon signed-rank test for B). Error bars, ± SEM.

To determine whether pC1 neurons are activated by ACh released from aSP-g neurons, we used the nicotinic ACh receptor (nAChR) blocker mecamylamine (MECA) and monitored the Ca2+ level in pC1 neurons with light stimulation of aSP-g neurons. Application of MECA inhibited the Ca2+ response of pC1 neurons induced by activating aSP-g neurons (Fig. 7B).

To identify the ACh receptors in pC1 neurons, we screened thirteen ACh receptors, including ten nAChRs and three muscarinic receptors [65–67], by knocking down their expression in pC1 neurons (Fig. S9A). The expression of UAS-nAChRα7-RNAi under the control of pC1-SS2 suppressed cVA-induced virgin female aggression (Fig. 7C). In addition, activating aSP-g neurons in the nAChRα7-null mutant did not promote virgin female aggression (Fig. 7D). Taken together, pC1 neurons receive direct cholinergic innervation from aSP-g neurons and are activated through nAChRα7 to regulate cVA-induced virgin female aggression.

Discussion

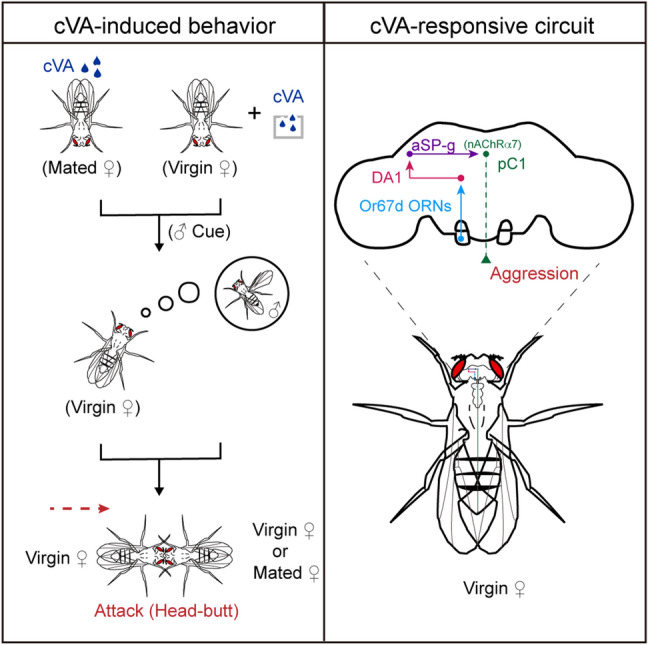

Whether and how female aggression is regulated by mating-related cues has been less investigated. Here, we found that virgin females initiated high-frequency attacks on mated females with a prior mating experience within 24 h. Specifically, we uncovered that cVA on mated females enhances aggression in virgin females. Behavioral and physiological tests demonstrated that cVA-responsive neurons in the first three layers of the olfactory system critically control female aggression. We further identified the fourth-order pC1 neurons, which receive cholinergic innervation from the third-order aSP-g neurons to mediate cVA-induced aggression. Thus, our data identify cVA as a mating-related inducer of virgin female aggression in Drosophila and reveal the underlying chemosensory circuit (Fig. 8A).

Fig. 8.

A model of the neural circuit involved in cVA-induced virgin female aggression. Left: male-specific cVA either from mated females or the environment can induce a virgin female attack. Right: cVA processed by a female-specific neural circuit promotes virgin female aggression.

There are three major reasons for the evolutionary selection of cVA as a trigger of virgin female aggression. First, cVA is exclusively produced by male flies to attract females [21, 27]. Virgin females increase aggression upon detecting cVA (Fig. 2), putatively to compete for access to males. Second, cVA is transferred to mated females during copulation [68] and suppresses male courtship to mated females [41]. If virgin females are near mated females, their mating opportunity will be conceivably reduced. Virgin females thus increase aggression to repel mated females to regain a normal mating opportunity. Third, cVA increases the attractiveness of food to both sexes as an aggregation pheromone [69, 70]. Upon detecting cVA, virgin females prefer to stay on food (Fig. S1) for better mating chances and for acquiring more reproductive resources to support prospective progeny. Therefore, in the presence of cVA and food, virgin females increase aggression towards other females regardless of mating experience to maximize their mating opportunity and resource acquisition.

Virgin females employ flexible competitive strategies through a nuanced perception of cVA. As a male-specific pheromone, the concentration of cVA may reflect the number of males nearby. A low cVA concentration indicates that males are rare and the mating opportunity is low. Virgin females thus respond by enhancing aggression (Fig. 2C). Accordingly, a high cVA concentration indicates that more males are available. Virgin females, therefore, respond in a peaceful way (Fig. 2C). Similar female aggression strategies may be used across species. For example, female house mice prefer to exhibit aggressive behaviors in contexts where there is one male available rather than three males [71]. In addition, the cVA concentration is significantly higher in mated females who just finished successful copulation, suggesting a potential mating partner nearby. Virgin females thus initiate attacks toward mated females with a high concentration of cVA deposited for a potential mating chance (Figs 1B–D and 2A). Because displaying aggressive behavior requires high energy consumption, virgin females may select to conserve energy for little mating chance nearby and did not attack 48-72 h mated females with little cVA deposit (Figs 1B–D and 2A), suggesting that females are sensitive to mating-related cues in a social context.

In Drosophila females, the first-, second-, and third-order olfactory neurons responsible for cVA information processing [27, 36, 59] and their neural circuit organization [36, 57, 58] have been identified in previous studies. However, the behavioral importance of DA1 PNs and aSP-g neurons remained unclear. The second-order DA1 PNs have similar cVA responses but send different projections to the lateral horn in males and females [59], activating sexually dimorphic third-order neurons. The sex-determination gene fru produces a sex-specific transcription factor to specify the neuronal morphology of the second- and third-order neurons responsible for cVA information processing [36, 59]. Our results revealed that fru+ DA1 PNs and aSP-g neurons regulate virgin female aggression (Fig. 4) and the masculinization of aSP-g suppresses cVA-induced virgin female aggression (Fig. S7), demonstrating that the female-specific cVA sensory pathway is important for appropriate behavioral output.

Central pC1 neurons respond to cVA [42], but their inputs that deliver cVA information have not been found. Here, we showed that aSP-g neurons directly innervate pC1 neurons to regulate virgin female aggression (Fig. 6). cVA elicits aggression in virgin females toward other females (Fig. 2) but increases their sexual receptivity toward males [21]. Notably, cVA-responsive pC1 neurons regulate both female aggression (Fig. 5) and receptivity [42]. We, therefore, infer that female pC1 neurons, like male P1 neurons [72, 73], function as an integration center of sensory information to regulate female behaviors. Proper behavioral output benefits survival and reproduction [74]. It remains obscure how the integration of complex sensory information influences the behavioral output in females, and future studies are thus warranted.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Bloomington Stock Center for fly stocks, as well as Yi Rao and Yufeng Pan for providing fly lines. We thank Hui Jiang, Xianhui Wang, Pengxiang Wu, and Liwei Zhang for their comments on the manuscript. We thank Jin Ge and Zhuxi Ge for providing suggestions for GC-MS analysis. We thank all members of the Chuan Zhou lab. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31872280 and 31622054), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Science (XDB11010800), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (E290D51135), and the Chinese Academy of Sciences (E129Q21105).

Competing interest

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Footnotes

Xiaolu Wan and Peng Shen contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Xiaolu Wan, Email: wanxiaolu@ioz.ac.cn.

Fengming Wu, Email: wufengming@ioz.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Rosvall KA. Intrasexual competition in females: Evidence for sexual selection? Behav Ecol. 2011;22:1131–1140. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arr106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pusey A, Williams J, Goodall J. The influence of dominance rank on the reproductive success of female chimpanzees. Science. 1997;277:828–831. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5327.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stockley P, Bro-Jørgensen J. Female competition and its evolutionary consequences in mammals. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2011;86:341–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo C, Pan Y, Gong Z. Recent advances in the genetic dissection of neural circuits in Drosophila. Neurosci Bull. 2019;35:1058–1072. doi: 10.1007/s12264-019-00390-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nilsen SP, Chan YB, Huber R, Kravitz EA. Gender-selective patterns of aggressive behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12342–12347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404693101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vrontou E, Nilsen SP, Demir E, Kravitz EA, Dickson BJ. Fruitless regulates aggression and dominance in Drosophila. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1469–1471. doi: 10.1038/nn1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan YB, Kravitz EA. Specific subgroups of FruM neurons control sexually dimorphic patterns of aggression in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19577–19582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709803104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han C, Peng Q, Sun M, Jiang X, Su X, Chen J, et al. The doublesex gene regulates dimorphic sexual and aggressive behaviors in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119:e2201513119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2201513119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palavicino-Maggio CB, Chan YB, McKellar C, Kravitz EA. A small number of cholinergic neurons mediate hyperaggression in female Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:17029–17038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1907042116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schretter CE, Aso Y, Robie AA, Dreher M, Dolan MJ, Chen N, et al. Cell types and neuronal circuitry underlying female aggression in Drosophila. Elife. 2020;9:e58942. doi: 10.7554/eLife.58942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiu H, Hoopfer ED, Coughlan ML, Pavlou HJ, Goodwin SF, Anderson DJ. A circuit logic for sexually shared and dimorphic aggressive behaviors in Drosophila. Cell. 2021;184:847. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deutsch D, Pacheco D, Encarnacion-Rivera L, Pereira T, Fathy R, Clemens J, et al. The neural basis for a persistent internal state in Drosophila females. Elife. 2020;9:e59502. doi: 10.7554/eLife.59502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu F, Deng B, Xiao N, Wang T, Li Y, Wang R, et al. A neuropeptide regulates fighting behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Elife. 2020;9:e54229. doi: 10.7554/eLife.54229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou C, Rao Y, Rao Y. A subset of octopaminergic neurons are important for Drosophila aggression. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1059–1067. doi: 10.1038/nn.2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ueda A, Kidokoro Y. Aggressive behaviours of female Drosophila melanogaster are influenced by their social experience and food resources. Physiol Entomol. 2002;27:21–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3032.2002.00262.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bath E, Morimoto J, Wigby S. The developmental environment modulates mating-induced aggression and fighting success in adult female Drosophila. Funct Ecol. 2018;32:2542–2552. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.13214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim RS, Eyjólfsdóttir E, Shin E, Perona P, Anderson DJ. How food controls aggression in Drosophila. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Anderson DJ. Identification of an aggression-promoting pheromone and its receptor neurons in Drosophila. Nature. 2010;463:227–231. doi: 10.1038/nature08678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernández MP, Chan YB, Yew JY, Billeter JC, Dreisewerd K, Levine JD, et al. Pheromonal and behavioral cues trigger male-to-female aggression in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chamero P, Marton TF, Logan DW, Flanagan K, Cruz JR, Saghatelian A, et al. Identification of protein pheromones that promote aggressive behaviour. Nature. 2007;450:899–902. doi: 10.1038/nature05997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butterworth FM. Lipids of Drosophila: A newly detected lipid in the male. Science. 1969;163:1356–1357. doi: 10.1126/science.163.3873.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guiraudie-Capraz G, Pho DB, Jallon JM. Role of the ejaculatory bulb in biosynthesis of the male pheromone cis-vaccenyl acetate in Drosophila melanogaster. Integr Zool. 2007;2:89–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4877.2007.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jallon JM. A few chemical words exchanged byDrosophila during courtship and mating. Behav Genet. 1984;14:441–478. doi: 10.1007/BF01065444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Goes van Naters W, Carlson JR. Receptors and neurons for fly odors in Drosophila. Curr Biol 2007, 17: 606–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Ha TS, Smith DP. A pheromone receptor mediates 11-cis-vaccenyl acetate-induced responses in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8727–8733. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0876-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu W, Liang X, Gong J, Yang Z, Zhang YH, Zhang JX, et al. Social regulation of aggression by pheromonal activation of Or65a olfactory neurons in Drosophila. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:896–902. doi: 10.1038/nn.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurtovic A, Widmer A, Dickson BJ. A single class of olfactory neurons mediates behavioural responses to a Drosophila sex pheromone. Nature. 2007;446:542–546. doi: 10.1038/nature05672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoyer SC, Eckart A, Herrel A, Zars T, Fischer SA, Hardie SL, et al. Octopamine in male aggression of Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2008;18:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng B, Li Q, Liu X, Cao Y, Li B, Qian Y, et al. Chemoconnectomics: Mapping chemical transmission in Drosophila. Neuron. 2019;101:876–893.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamada FN, Rosenzweig M, Kang K, Pulver SR, Ghezzi A, Jegla TJ, et al. An internal thermal sensor controlling temperature preference in Drosophila. Nature. 2008;454:217–220. doi: 10.1038/nature07001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenett A, Rubin GM, Ngo TTB, Shepherd D, Murphy C, Dionne H, et al. A GAL4-driver line resource for Drosophila neurobiology. Cell Rep. 2012;2:991–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pfeiffer BD, Jenett A, Hammonds AS, Ngo TTB, Misra S, Murphy C, et al. Tools for neuroanatomy and neurogenetics in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9715–9720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803697105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rideout EJ, Dornan AJ, Neville MC, Eadie S, Goodwin SF. Control of sexual differentiation and behavior by the doublesex gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:458–466. doi: 10.1038/nn.2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, et al. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Philipsborn AC, Liu T, Yu JY, Masser C, Bidaye SS, Dickson BJ. Neuronal control of Drosophila courtship song. Neuron. 2011;69:509–522. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kohl J, Ostrovsky AD, Frechter S, Jefferis GSXE. A bidirectional circuit switch reroutes pheromone signals in male and female brains. Cell. 2013;155:1610–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang F, Wang K, Forknall N, Patrick C, Yang T, Parekh R, et al. Neural circuitry linking mating and egg laying in Drosophila females. Nature. 2020;579:101–105. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2055-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu H, Kubli E. Sex-peptide is the molecular basis of the sperm effect in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9929–9933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1631700100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Branson K, Robie AA, Bender J, Perona P, Dickinson MH. High-throughput ethomics in large groups of Drosophila. Nat Methods. 2009;6:451–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Billeter JC, Atallah J, Krupp JJ, Millar JG, Levine JD. Specialized cells tag sexual and species identity in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 2009;461:987–991. doi: 10.1038/nature08495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ejima A, Smith BPC, Lucas C, van der Goes van Naters W, Miller CJ, Carlson JR, et al. Generalization of courtship learning in Drosophila is mediated by cis-vaccenyl acetate. Curr Biol 2007, 17: 599–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Zhou C, Pan Y, Robinett CC, Meissner GW, Baker BS. Central brain neurons expressing doublesex regulate female receptivity in Drosophila. Neuron. 2014;83:149–163. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou C, Franconville R, Vaughan AG, Robinett CC, Jayaraman V, Baker BS. Central neural circuitry mediating courtship song perception in male Drosophila. Elife. 2015;4:e08477. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rohlfing T, Maurer CR. Nonrigid image registration in shared-memory multiprocessor environments with application to brains, breasts, and bees. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2003;7:16–25. doi: 10.1109/TITB.2003.808506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rohlfing T. Image similarity and tissue overlaps as surrogates for image registration accuracy: Widely used but unreliable. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2012;31:153–163. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2011.2163944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jefferis GSXE, Potter CJ, Chan AM, Marin EC, Rohlfing T, Maurer CR, Jr, et al. Comprehensive maps of Drosophila higher olfactory centers: Spatially segregated fruit and pheromone representation. Cell. 2007;128:1187–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang SX, Miner LE, Boutros CL, Rogulja D, Crickmore MA. Motivation, perception, and chance converge to make a binary decision. Neuron. 2018;99:376–388.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scheffer LK, Xu CS, Januszewski M, Lu Z, Takemura SY, Hayworth KJ, et al. A connectome and analysis of the adult Drosophila central brain. Elife. 2020;9:e57443. doi: 10.7554/eLife.57443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bath E, Bowden S, Peters C, Reddy A, Tobias JA, Easton-Calabria E, et al. Sperm and sex peptide stimulate aggression in female Drosophila. Nat Ecol Evol. 2017;1:0154. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mane SD, Tompkins L, Richmond RC. Male esterase 6 catalyzes the synthesis of a sex pheromone in Drosophila melanogaster females. Science. 1983;222:419–421. doi: 10.1126/science.222.4622.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tram U, Wolfner MF. Seminal fluid regulation of female sexual attractiveness in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4051–4054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sureau G, Ferveur JF. Co-adaptation of pheromone production and behavioural responses in Drosophila melanogaster males. Genet Res. 1999;74:129–137. doi: 10.1017/S0016672399003936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang L, Han X, Mehren J, Hiroi M, Billeter JC, Miyamoto T, et al. Hierarchical chemosensory regulation of male-male social interactions in Drosophila. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:757–762. doi: 10.1038/nn.2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laughlin JD, Ha TS, Jones DNM, Smith DP. Activation of pheromone-sensitive neurons is mediated by conformational activation of pheromone-binding protein. Cell. 2008;133:1255–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kitamoto T. Conditional modification of behavior in Drosophila by targeted expression of a temperature-sensitive shibire allele in defined neurons. J Neurobiol. 2001;47:81–92. doi: 10.1002/neu.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gao XJ, Riabinina O, Li J, Potter CJ, Clandinin TR, Luo L. A transcriptional reporter of intracellular Ca(2+) in Drosophila. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:917–925. doi: 10.1038/nn.4016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stockinger P, Kvitsiani D, Rotkopf S, Tirián L, Dickson BJ. Neural circuitry that governs Drosophila male courtship behavior. Cell. 2005;121:795–807. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cachero S, Ostrovsky AD, Yu JY, Dickson BJ, Jefferis GS. Sexual dimorphism in the fly brain. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1589–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Datta SR, Vasconcelos ML, Ruta V, Luo S, Wong A, Demir E, et al. The Drosophila pheromone cVA activates a sexually dimorphic neural circuit. Nature. 2008;452:473–477. doi: 10.1038/nature06808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jefferis GSXE, Vyas RM, Berdnik D, Ramaekers A, Stocker RF, Tanaka NK, et al. Developmental origin of wiring specificity in the olfactory system of Drosophila. Development. 2004;131:117–130. doi: 10.1242/dev.00896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baines RA, Uhler JP, Thompson A, Sweeney ST, Bate M. Altered electrical properties in Drosophila neurons developing without synaptic transmission. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1523–1531. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01523.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sweeney ST, Broadie K, Keane J, Niemann H, Okane CJ. Targeted expression of tetanus toxin light chain in Drosophila specifically eliminates synaptic transmission and causes behavioral defects. Neuron. 1995;14:341–351. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nicolaï LJJ, Ramaekers A, Raemaekers T, Drozdzecki A, Mauss AS, Yan J, et al. Genetically encoded dendritic marker sheds light on neuronal connectivity in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20553–20558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010198107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Klapoetke NC, Murata Y, Kim SS, Pulver SR, Birdsey-Benson A, Cho YK, et al. Independent optical excitation of distinct neural populations. Nat Methods. 2014;11:338–346. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Littleton JT, Ganetzky B. Ion channels and synaptic organization: Analysis of the Drosophila genome. Neuron. 2000;26:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Collin C, Hauser F, de Valdivia EG, Li S, Reisenberger J, Carlsen EMM, et al. Two types of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in Drosophila and other arthropods. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:3231–3242. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1334-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Onai T, FitzGerald MG, Arakawa S, Gocayne JD, Urquhart DA, Hall LM, et al. Cloning, sequence analysis and chromosome localization of a Drosophila muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. FEBS Lett. 1989;255:219–225. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jallon JM, Antony C, Benamar O. An anti-aphrodisiac produced by Drosophila melanogaster males and transferred to females during copulation. C R Acad Sci Ser III Sci Vie. 1981;292:1147–1149. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bartelt RJ, Schaner AM, Jackson LL. Cis-Vaccenyl acetate as an aggregation pheromone inDrosophila melanogaster. J Chem Ecol. 1985;11:1747–1756. doi: 10.1007/BF01012124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mercier D, Tsuchimoto Y, Ohta K, Kazama H. Olfactory landmark-based communication in interacting Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2018;28:2624–2631.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rusu AS, Krackow S. Kin-preferential cooperation, dominance-dependent reproductive skew, and competition for mates in communally nesting female house mice. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2004;56:298–305. doi: 10.1007/s00265-004-0787-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Clowney EJ, Iguchi S, Bussell JJ, Scheer E, Ruta V. Multimodal chemosensory circuits controlling male courtship in Drosophila. Neuron. 2015;87:1036–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang W, Guo C, Chen D, Peng Q, Pan Y. Hierarchical control of Drosophila sleep, courtship, and feeding behaviors by male-specific P1 neurons. Neurosci Bull. 2018;34:1105–1110. doi: 10.1007/s12264-018-0281-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gao C, Guo C, Peng Q, Cao J, Shohat-Ophir G, Liu D, et al. Sex and death: Identification of feedback neuromodulation balancing reproduction and survival. Neurosci Bull. 2020;36:1429–1440. doi: 10.1007/s12264-020-00604-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.