Abstract

The rise of nanotechnology has opened new horizons for cancer immunotherapy. However, most nanovaccines fabricated with nanomaterials suffer from carrier-related concerns, including low drug loading capacity, unpredictable metabolism, and potential systemic toxicity, which bring obstacles for their clinical translation. Herein, we developed an antigen self-assembled nanovaccine, which was resulted from a simple acryloyl modification of the antigen to induce self-assembly. Furthermore, a dendritic cell targeting head mannose monomer and a mevalonate pathway inhibitor zoledronic acid (Zol) were integrated or absorbed onto the nanoparticles (denoted as MEAO-Z) to intensify the immune response. The synthesized nanovaccine with a diameter of around 70 nm showed successful lymph node transportation, high dendritic cell internalization, promoted costimulatory molecule expression, and preferable antigen cross-presentation. In virtue of the above superiorities, MEAO-Z induced remarkably higher titers of serum antibody, stronger cytotoxic T lymphocyte immune responses and IFN-γ secretion than free antigen and adjuvants. In vivo, MEAO-Z significantly suppressed EG7-OVA tumor growth and prolonged the survival time of tumor-bearing mice. These results indicated the translation promise of our self-assembled nanovaccine for immune potentiation and cancer immunotherapy.

Keywords: Subunit antigen, Self-assembled nanovaccine, Dendritic cell, Mannose receptor, Zoledronic acid, Antigen cross-presentation, Cellular immunity, Cancer immunotherapy

Graphical abstract

An antigen self-assembled and dendritic cell-targeted nanovaccine promoted lymph node transport, enhanced dendritic cells internalization and antigen cross-presentation, thereby eliciting the potent immune responses against cancer.

1. Introduction

Cancer immunotherapy was developed to elicit system immune response against cancer and has been recognized as a desirable alternative to conventional cancer remedies1,2. The induced cancer antigen-specific immunity can recognize and eliminate cancerous cells while causing negligible damage to normal cells, whereas the induced immune memory also provides long-term protection against cancer regeneration3, 4, 5. In recent years, cancer vaccines based on nano-delivery systems have received particular attention. These nano-systems have multiple advantages as compared to free antigen/adjuvant, such as improved stability of antigens, the ability to co-deliver antigens and adjuvants, the efficient drainage to lymph nodes, the preferable antigen-presenting cells (APCs) uptake, the tunable intracellular release, and the enhanced antigen cross-presentation, etc6, 7, 8.

As numerous synthetic or bioderived nanoparticles have been extensively investigated for vaccine delivery, there has been an increased concern of their biocompatibility. The intrinsic drawbacks of the additional indispensable nanomaterials, including complicated preparation, uncertain degradation, unpredictable metabolism, and potential systemic toxicity, immensely restrict the clinical application of nanovaccines9,10. For instance, edema and cytoplasmic damage were seen in the liver cells after intraperitoneal injection of iron oxide nanoparticles11. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles also showed hepatotoxicity due to their ineffective biodegradability and tendentious accumulation in the liver12. Besides, elevated serum creatinine level that reflected impaired renal function was observed after in vivo application of cationic liposomes and micelles13. Hence, there is an urgent demand for carrier-independent nanovaccine fabricated with green and facile methods.

A promising strategy to meet these challenges is to fabricate nanovaccines by direct self-assembly or self-crosslinking of antigens14,15, which ensures high antigen loading while nearly no use of exterior carrier materials. Nevertheless, some reported assembling or crosslinking methods involve harsh reaction conditions, such as long-time heating16, violent mechanical stirring17,18, extreme pH conditions19, and the use of irritant organic reagents20, which may cause an unavoidable impact on antigen activity. Encouragingly, self-assembled nanotechnology based on free radical reactions provides a new perspective for the preparation of nanoparticles21, 22, 23, 24. Firstly, acryloyl modification was carried out on the amino groups of protein to generate polymerizable capacity. Then, free radicals generated from polymerizable groups enable the reticular assembly to obtain a stable nanoparticle under the catalysis of active oxygen. The whole preparation process is efficient, mild, and does not involve operations that may denature the proteins. This strategy is also applicable for an extensive range of subunit antigens because the modification site is the abundant amino group on the surface of all proteins.

However, a strong immune response is not necessarily able to be elicited by simple preparation of subunit antigens into nanovaccines. Delivering the nanovaccines to APCs as much as possible, especially dendritic cells (DCs) that can activate Naïve T cells, is critical for eliciting immune responses25,26. By preparing nanoparticles sized between 10–100 nm, antigens can be effectively transported to DCs-enriched lymph node sites after subcutaneous injection. Further, we need to adopt some strategies to improve DCs' uptake. Plenty of evidence showed that mannose receptor (MR) is abundantly expressed on the surface of DCs27,28. Therefore, the application of mannose ligand is a feasible strategy for improving DCs’ uptake29, 30, 31. After internalization by DCs, only effective cross-presentation of exogenous antigens can activate CD8+ T cells to elicit a strong therapeutic efficacy against cancer32. Zoledronic acid (Zol), one of the third-generation nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates, can interrupt farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase in the mevalonate pathway and further inhibit the production of small GTPases. The decrease of small GTPases in DCs, such as Rab5, directly retards endosomal maturation, delays antigen entry into the degradative lysosome, thus enhancing antigen cross-presentation and CD8+ T cell activation. In addition, Zol has been clinically approved and therefore appears to be safe and feasible to be used as a regulator to construct cancer nanovaccine33,34.

In the current study, we developed a self-assembled nanovaccine constituted from mannosylated protein antigen to enhance the immune response against cancer. The scheme is shown in Fig. 1. The approach is to self-assemble antigen (ovalbumin) and mannose monomer (allyl-d-mannopyranoside) at the nanoscale with the assistance of a crosslinker (ethylene glycol dimethacrylate, EMA). Additionally, a positively charged monomer [N-(3-aminopropyl) methacrylamide hydrochloride, Apm] was introduced during the self-assembly process to obtain a cationic nanovaccine (MEAO). Zoledronic acid (Zol) was used as an adjuvant and absorbed on the surface of MEAO via electrostatic interaction (MEAO-Z). In this fashion, we minimized the use of extra materials to fabricate nanoparticles and maximized the benefits of nanosized systems to efficiently co-deliver antigen and adjuvant to DCs located in lymph nodes. Our experimental results revealed that MEAO-Z significantly promoted antigen cross-presentation and elicited a robust cytotoxic T cell response. MEAO-Z also showed superior anti-tumor potency in an EG7-OVA lymphoma mice model.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of engineered “antigen self-assembled” nanovaccine for cancer immunotherapy. Firstly, the approach was to crosslink antigen (polymerizable ovalbumin), mannose monomer (allyl-d-mannopyranoside), and electropositive monomer [N-(3-aminopropyl) methacrylamide hydrochloride (Apm)] based on free-radical reactions at the nanoscale for structural formation. Zoledronic acid as an adjuvant was absorbed via electrostatic interaction to form MEAO-Z. Secondly, nanovaccines drained to lymph nodes after subcutaneous injection and were internalized by resident dendritic cells. Intracellular processing preceded the recognition of antigen by T lymphocytes. Ultimately, a robust antigen-specific immune response was elicited which showed a significant impetus for cancer immunotherapy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

d-Mannose, allyl alcohol, N-acryloxysuccinimide (NAS), ammonium persulfate (APS), N-(3-aminopropyl) methacrylamide hydrochloride (Apm), ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EMA), and fluorescamine were purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). Ovalbumin (OVA), and N,N,N′,Nʹ′-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) were purchased from Sigma‒Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Zoledronic acid (Zol) was purchased from J&K Scientific Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640 (RPMI-1640) medium and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Gibco (Beijing, China). Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) was purchased from Bio-Techne (St. Louis, MO, USA). Fluorochrome-labeled anti-mouse CD11c, SIINFEKL/H-2Kb, CD40, CD80, CD86, F4/80, CD4, CD8a, IL-4, IFN-γ, CD44 and CD62L antibodies were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). BCA protein assay kit and enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay (ELISA) kits for IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (San Diego, CA, USA). Mouse IFN-γ ELISPOT kit was purchased from Dakewe Biotech (Beijing, China). Ninety-six well plates were obtained from NEST Biotechnology (Wuxi, China). All the other chemicals used are analytical grade or HPLC grade, and ultrapure water was used for solution preparation.

2.2. Cells and animals

DC2.4 murine dendritic cells (obtained from the Third Military Medical University) and EG7-OVA cells (obtained from American Type Culture Collection) were both cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and streptomycin-penicillin (1%, v/v) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere incubator containing 5% CO2. Female C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks old) were purchased from Chengdu Dossy Experimental Animals Co., Ltd. The mice were kept in a standard animal room, with strict temperature and humidity control, light diurnal cycle, and free access to standard feed and water. All animal experiments were conducted according to the guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Ethics Committee of Sichuan University (Chengdu, China).

2.3. Synthesis of allyl-d-mannopyranoside and polymerizable ovalbumin

Allyl-d-mannopyranoside was synthesized by conjugating d-mannose with allyl alcohol using an ether bond as linkage with a method as previously described35. The reaction system was heated up to 90 °C in a reflux system for 1.5 h after thoroughly mixing pretreated resin, allyl alcohol, and d-mannose. Then the filtered mixture was collected and further purified by column chromatography using ethyl acetate/isopropanol/ultrapure water (9:4:2, v/v/v) as eluent. The product was characterized using hydrogen nuclear magnetic spectra (1H NMR). 1H NMR spectra was obtained on a Bruker 400 MHz spectrometer (Karlsruhe, Germany), and the chemical shifts were measured with D2O as the internal reference (D2O: δ = 4.79 ppm).

Polymerizable ovalbumin was synthesized by modifying ovalbumin with acryloyl groups. N-Acryloxysuccinimide (100 mg/mL, in DMSO) was added dropwise into OVA solution (5 mg/mL, in 20 mmol/L sodium carbonate buffer, pH 8.5) with a molar ratio of 20:1 (N-acryloxysuccinimide:OVA). The mixture was mildly stirred on a magnetic stirrer at 4 °C for 4 h and then dialyzed against (dialysis bag, cut off 10 kD) ultrapure water for 4 h to obtain purified polymerizable OVA27. The modification degree of acryloyl groups on ovalbumin was measured by a fluorescamine kit. Firstly, a series of OVA and polymerizable OVA aqueous solutions at equal concentrations were prepared and added (100 μL each) to the 96-well black plate. Then, 30 μL of fluorescamine (3 mg/mL, in DMSO) was added to the plate and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 1 h. The fluorescence intensity (FI) at the excitation wavelength of 360 nm and emission wavelength of 465 nm was measured and the modification degree of acryloyl groups on ovalbumin was calculated according to Eq. (1):

| Average number of acryloylgroups conjugated=n×(1–FI of polymerizable OVA reacted with fluorescamine/FI of OVA reacted with fluorescamine) | (1) |

where n refers to the amount of lysine on the surface of OVA.

2.4. Preparation and characterization of nanoparticles

To prepare MEO, polymerizable OVA was mixed with mannose monomers, and the assembling of nanoparticles was induced by free radical in situ polymerization reaction under anaerobic conditions. Firstly, with a molar ratio of 3000:1, 200 μL of allyl-d-mannopyranoside (30 mg/mL, in 5 × PBS) was added dropwise to 200 μL of polymerizable OVA solution (5 mg/mL, in 5 × PBS). After stirring thoroughly, 3 μL of cross-linking agent EMA was added, and the total reaction volume was limited to 1 mL22. Under anaerobic conditions, the free radical generator APS aqueous solution (27 μL, 100 mg/mL) and initiator TEMED solution (20 μL, 10% diluted in DMSO) were added and reacted for 2 h at room temperature. Afterward, the mixture was dialyzed against 1 × PBS solution (dialysis bag, cut off 10 kD) for 4 h to obtain purified nanoparticles. MEAO was fabricated with the same method as mentioned above, with the only difference that a positively charged regulator Apm (90 μL, 50 mg/mL, in 5 × PBS) was added in the first preparation step. To load Zol into MEAO, Zol aqueous solution (12.5 μL, 2 mg/mL) was added dropwise to MEAO (87.5 μL, containing 20 μg OVA) solution with gentle mixing by vortex mixer. The encapsulation efficiency of OVA was quantified by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method following the manufacturer's instruction. The encapsulation efficiency of Zol was measured using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (1260 Infinity, Agilent technologies, Palo alto, CA, USA). Unencapsulated Zol was collected by centrifugation (Beckman Coulter, Allegra X-30, Kraemer Boulevard Brea, CA, USA) in an ultrafiltration tube (cut off 10 kD) at the speed of 800×g for 15 min (Beckman Coulter). The mobile phase consisted of the organic phase and aqueous phase at the volume ratio of 5:95. The organic phase contains 80% acetonitrile and 20% tetrahydrofuran. The aqueous phase was prepared by diluting 6 mL of tetrabutylammonium hydroxide to 1 L with ultra-pure water and adjusting the pH to 3 with 50% (v/v) phosphoric acid. The flow rate of the mobile phase was 1 mL/min. The encapsulation efficiency was calculated according to Eq. (2):

| Encapsulation efficiency (%) = (Weight of encapsulated drug / Weight of drug added) × 100 | (2) |

To preliminarily determine whether OVA was crosslinked to form the nanoparticles, ultraviolet absorptions at wavelength below 400 nm of free-OVA, MEO, and MEAO were detected with AquaMate 8100 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, San Diego, CA, USA). Size distribution and zeta potential of the nanoparticles were analyzed by dynamic light scattering and electrophoretic light scattering, respectively, using Zetasizer Nano ZS90 instrument (Malvern, Worcestershire, UK). The surface morphology of the nanoparticles was visualized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, H-600, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Firstly, several droplets of the diluted sample solution were added to the carbon-coated copper mesh and dried for 2 min. Afterward, 1% tungstate acid solution was added and the samples were stained for 3 min. Finally, the nanoparticles were visualized by TEM (H-600, Hitachi) with an accelerating voltage of 70 kV. To visualize the surface morphology of degraded nanoparticles, the nanoparticles were incubated in acetic acid (pH = 5.4) for 7 h and visualized by TEM (H-600, Hitachi) with the same procedures as mentioned above.

2.5. Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of mannosylated ovalbumin nanoparticles was detected by Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. DC2.4 and L929 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (1 × 104 cells/well) and cultivated for 24 h. After that, the culture medium was replaced by nanoparticles containing different concentrations of OVA ranging from 10 to 250 μg/mL. The cells treated with fresh culture medium were used as a control. After incubating for another 24 h, 10 μL of CCK-8 reagent was added to each well and incubated for 4 h. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific Varioskan Flash, San Diego, CA, USA) and the cells relative viability was calculated according to Eq. (3):

| Cell relative viability (%)= (Absorbance value of sample group / Absorbance value of control group) × 100 | (3) |

2.6. In vitro cellular uptake and mechanism studies

For the quantitative analysis of cellular uptake, DC2.4 cells (1 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in 12-well plates and cultivated for 8 h. After that, the cells were exposed to free OVA, MEO, MEAO, or MEAO-Z containing a final fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) labeled OVA concentration of 10 μg/mL at 37 °C for 1 h. Next, the cells were collected by centrifugation at a speed of 400×g for 4 min (Beckman Coulter), washed twice with PBS. Finally, the percentage of FITC-positive cells was analyzed by flow cytometer (BD FACS Celesta, New York, NY, USA).

To explore the endocytosis mechanisms of mannosylated ovalbumin nanoparticles in DC2.4 cells, we pretreated the cells with inhibitors of different internalization pathways at 37 °C for 1 h. The following endocytosis inhibitors were used: dextran sulfate that inhibit scavenger receptor-mediated endocytosis (100 μg/mL)36, chlorpromazine that inhibit clathrin-mediated endocytosis (5 μg/mL)37, nystatin that inhibit caveolin-mediated endocytosis (25 μg/mL)38, and amiloride that inhibit macropinocytosis-mediated endocytosis (26 μg/mL)39. Next, the cells were incubated with MEO, MEAO, or MEAO-Z containing 10 μg/mL FITC-OVA for another 1 h. The cells were also treated at 4 °C to investigate the influence of energy suppression induced by low temperature on the cellular uptake of the nanoparticles. After incubation, the cells were collected by centrifugation at a speed of 400×g for 4 min (Beckman Coulter), and the proportions of FITC-positive cells were analyzed by flow cytometer (BD FACS Celesta).

2.7. In vitro lysosomal escape and antigen cross-presentation

The capacity of nanoparticles to promote cytosolic delivery was evaluated on bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs). As described previously, BMDCs were generated from C57BL/6 mice bone marrow40. Firstly, the femurs and tibiae were obtained after removing the skin and muscle tissues of the hind legs. Then, the bones were soaked in 75% ethyl alcohol for 10 min. Both ends of the bones were cut down, and the marrow was obtained by flushing the cavity of bones repeatedly by RPMI-1640 medium with an 1-mL inserted syringe. Afterward, the cell suspension was filtered using a 70 μm nylon mesh (Biologix, Chengdu, China) to remove bones scrap and blood patches. Finally, 2 × 107 cells were cultured in a non-tissue-culture-coated Petri dish with RPMI-1640 medium containing 20 ng/mL GM-CSF. On Day 3, equal 10 mL of fresh RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with GM-CSF was added to the dish. On Day 5, the nonadherent cell colonies distributed on the dishes were collected gently. The purity of BMDCs was determined by measuring the proportion of CD11c-positive cells with a flow cytometer. If the proportion was higher than 85%, the obtained BMDCs were used. To study the lysosomal escape, BMDCs were incubated for 1 or 5 h with MEO, MEAO, or MEAO-Z containing 10 μg/mL FITC-OVA in confocal dishes. The cells were stained with LysoTracker Red for 30 min and washed with PBS for three times. Then the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and followed by staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 5 min. After that, the intracellular fluorescent signal was observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany).

To investigate the ability of nanoparticles to promote cross-presentation, BMDCs were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 2 × 106 cells per well and incubated for 18 h with different formulations containing 10 μg OVA. In the group of MEAO-Z + GGOH, 25 μg geranylgeraniol (GGOH) was added after MEAO-Z had been incubated with BMDCs for 4 h, and then co-cultured for the rest of 14 h. Finally, BMDCs were collected by centrifugation at a speed of 200×g for 10 min (Beckman Coulter), and stained with PE-anti-mouse H-2kb-SIINFEKL antibody. Finally, the proportion of PE-positive cells was detected by flow cytometry (BD FACS Celesta).

2.8. In vitro activation of BMDCs

To verify the capacity of nanoparticles to stimulate BMDC maturation, the cells seeded in 12-well plates were incubated with different nanoparticles for 24 h. BMDCs incubated with 2 μg lipopolysaccharide (LPS) were used as a positive control. After thrice washing with PBS, BMDCs were stained with PE-anti-mouse CD40, FITC-anti-mouse CD80, and APC-anti-mouse CD86 antibodies. Flow cytometry was used to detect the expression of costimulatory molecules CD40, CD80, and CD86 on the surface of BMDCs. Besides, the cell culture supernatants were collected and analyzed by enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay (ELISA) for IL-6 and TNF-α cytokines secretion following the manufacturer's instruction. Firstly, costar™ 9018 ELISA plates were pre-coated with 100 μL/well of anti-mouse IL-6 or TNF-α antibody as the capture antibody in coating buffer. The plates were sealed with plastic wrap and incubated overnight at 4 °C. On the next day, each well of the plates was washed thrice with 250 μL of washing buffer (1 × PBS supplemented with 0.05% tween-20) and blocked with 200 μL of ELISA diluent at 37 °C for 1 h. Then, a set of standards were prepared according to the reagent preparation procedure. Samples and 100 μL of standard reagents were added to the appropriate wells. After incubating for another 2 h, a biotin-conjugated anti-mouse IL-6 or TNF-α antibody was added to the washed plates as the detection antibody. Following that, the plates were washed five times and diluted streptavidin-HRP was added into each well. After incubating for half an hour, the plates were washed seven times and incubated with 100 μL/well tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) for 15 min. Finally, 50 μL/well of 20% (v/v) sulfuric acid were added into the wells and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific Varioskan Flash).

2.9. Lymph node targeting assay

To observe the distribution of nanoparticles in lymph nodes, free OVA, MEO, or MEAO containing 20 μg FITC-OVA were subcutaneously injected into the tail base of female C57BL/6 mice. After 14 h, the mice were sacrificed, and ipsilateral inguinal draining lymph nodes were harvested. The lymph nodes were cryosectioned with the section thickness of 10 μm using a freezing microtome (Lecia CM1950, Heidelberg, Germany), and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. After being washed thrice with PBS, the frozen sections were stained with DAPI to visualize the nucleus. The fluorescent images were obtained using a confocal laser scanning microscope (ZEISS).

To evaluate whether the nanoparticles could be internalized by lymph node-resident cells, especially APCs, free OVA, MEO, or MEAO containing 20 μg FITC-OVA were subcutaneously injected in the tail base of C57BL/6 mice. Their ipsilateral inguinal draining lymph nodes were harvested at different desired time points including 3, 10, 17, and 24 h. After gently grounding the lymph node through 70 μm nylon mesh, the obtained single-cell suspension was stained with diluted APC-anti-mouse CD11c and PE-anti-mouse F4/80 antibodies, and then the percentages of FITC-positive in all cells, APC-positive cells, or PE-positive cells were measured by flow cytometry (BD FACS Celesta).

2.10. Animal immunization

Female C57BL/6 mice were subcutaneously immunized in the tail base with the following formulations: free OVA, MEO, MEAO, MEAO-Z, or OVA + Zol which contained 20 μg OVA and with or without 25 μg Zol. The control group received PBS. Primary immunization was recorded as Day 0, and the booster immunizations were given on Days 7 and 14. Finally, the vaccinated mice were sacrificed on Day 21, and blood and spleens were collected for further immunity analysis.

OVA-specific antibodies in serum were detected by ELISA kit as described previously41. Firstly, each well of 96-well plates was precoated with 1 μg OVA as the coating antigen at 4 °C overnight. Then, the plates were washed twice and blocked with 1% BSA in PBS (100 μL per well) at 37 °C for 1 h. After blocking, appropriate three-fold serial dilutions of serum samples were applied to the plates and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Then the plates were washed at least five times, and 100 μL horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antibodies against IgG, IgG1, IgG2a (1:10,000 dilution) were added and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After washing, the plates were incubated with 100 μL/well tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) for 15 min. Finally, 50 μL/well of 20% (v/v) sulfuric acid were added into the wells for reaction stop. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific Varioskan Flash). After fitting the S curves according to the dilution factor and absorbance value, nonlinear regression analyses were performed to calculate the logEC50 value as an indicator of serum titers.

In addition, the spleens were collected and gently ground through a 70 μm nylon mesh to obtain a single-cell suspension. Firstly, the splenocytes were incubated with ammonium chloride potassium (ACK) lysis buffer for 8 min to remove red blood cells. Then the splenocytes were washed with PBS and resuspended in RPMI-1640 culture medium. The cells were planted in 12-well plates at a density of 1.5 × 107 cells per well. To detect intracellular cytokine secreting in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, splenocytes were pre-incubated with 100 μg/mL OVA and 2 μg/mL SIINFEKL peptide for 1 h. Afterward, 5 μg/mL brefeldin A was added and the cells were incubated for another 5 h. The splenocytes in the plates were collected by centrifugation at a speed of 400 g for 4 min (Beckman Coulter). The cells were resuspended in 50 μL of PBS supplemented with 2% FBS. Then, 50 μL of diluted surface staining antibodies, including APC-eFluor 780-anti-mouse CD4 and FITC-anti-mouse CD8 were added in each sample and incubated with the cells for 30 min at 4 °C. After washing twice with PBS, the cells were resuspended in freshly fixation buffer and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. The cells were then washed twice with permeabilization solution and stained with 100 μL of diluted intracellular cytokines antibodies containing PE-anti-mouse IL-4 and APC-anti-mouse IFN-γ in the darkness for another 30 min. Finally, after washing with PBS, the percentage of IL-4+CD4+ and IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells was detected by flow cytometer (BD FACS Celesta).

In splenocyte proliferation, cytokine secretion, and immune memory detection experiments, the splenocytes were stimulated with the same concentration of OVA antigen and SIINFEKL peptide as described above for 72 h. Briefly, 2 × 105 cells were seeded into each well of 96-well plates in the experiment of splenocytes proliferation detection. Meanwhile, blank RPMI-1640 medium was added into the wells of each sample as a control group. On Day 3, 10 μL of CCK-8 working reagent was added to each well, and the absorption at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader. The proliferation index was calculated by dividing the absorbance value of the stimulated group by that of the control group. In cytokine secretion and immune memory detection experiments, the splenocytes were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 5 × 106 per well. On Day 3, the culture supernatant was collected to analyze the secretion of IFN-γ by ELISA as described above. Meanwhile, the cells were collected for surface markers staining, including APC-eFluor 780-anti-mouse CD4, FITC-anti-mouse CD8, PE-anti-mouse CD44, and APC-anti-mouse CD62L. Afterward, the percentage of CD44+CD62L+ in CD4+ or CD8+ T cells was measured by flow cytometer (BD FACS Celesta).

For the enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISPOT), the mouse IFN-γ ELISPOT kit was used according to the working manual. Firstly, a mouse lymphocyte separation solution was used to isolate T lymphocytes from splenocytes. The concentration of T lymphocyte samples was adjusted to 1 × 107 cells/mL and 100 μL of cells were added into each well of mouse IFN-γ precoated 96-well polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) plates. T lymphocytes were stimulated with SIINFEKL peptide (2 μg/mL) at 37 °C for 20 h. The samples treated with blank medium and phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) were used as a negative control and positive control, respectively. After a series of processing operations according to the working manual, IFN-γ spots were analyzed using a plate reader (Bioreader4000, Biosys, Frankfurt, Germany).

2.11. In vivo CTL response

Female C57BL/6 mice were immunized with different formulations as described above. Seven days after the last immunization, the mice were injected intravenously with 1 × 107 carboxy-fluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled cells. The CFSE-labeled cells were prepared as below: spleen harvested from naïve mouse was ground through 70 μm nylon mesh to obtain a single splenocyte suspension. The splenocytes were equally divided. One half of them were incubated with 2 μg/mL SIINFEKL peptide for 1 h, and another half with blank RPMI-1640 complete medium. SIINFEKL-pulsed splenocytes were labeled with 4 μmol/L CFSE (denoted as CFSEhigh), and medium-treated splenocytes were labeled with 0.4 μmol/L CFSE (denoted as CFSElow). Finally, the two CFSE-labeled splenocytes were equally mixed to obtain the target cells, and 1 × 107 cells were intravenously injected into the vaccinated mice as mentioned above. Twenty hours after injection, the mice were sacrificed, and splenocytes were collected and evaluated by flow cytometer (BD FACS Celesta). The proportion of OVA-specific lysis was calculated according to Eq. (4):

| OVA-specific lysis (%) = [1 − (CFSElow/CFSEhigh cells of naïve mice) / (CFSElow/CFSEhigh cells of immunized mice)] × 100 | (4) |

2.12. Tumor challenge

To test the therapeutic efficacy of the fabricated nanovaccine, female C57BL/6 mice were subcutaneously implanted with 5 × 105 EG7-OVA cells on Day 0. Then, the mice were injected with different formulations, including PBS, OVA, OVA + Zol, MEO, MEAO, and MEAO-Z on Days 3, 7, and 11, which contained 20 μg OVA and with or without 25 μg Zol. The length and width of the tumor were measured by vernier caliper every two days, and the tumor volume was calculated according to Eq. (5):

| V = Length × Width2 / 2 | (5) |

The mice were euthanized out of humanitarian concern when the length of tumor exceeded 2 cm, or the tumor volume exceeded 2000 mm3.

2.13. Immune cell populations in tumors

To investigate the capability of fabricated nanovaccines to generate immune activation in the tumor microenvironment, female C57BL/6 mice were subcutaneously implanted with 5 × 105 EG7-OVA cells on Day 0. Then, the mice were injected with different formulations, including PBS, OVA, OVA + Zol, MEO, MEAO, and MEAO-Z on Days 3, 7, and 11, which contained 20 μg OVA and with or without 25 μg Zol. Finally, the tumor-bearing mice were sacrificed on Day 16, and tumors were collected for further immunity analysis. The harvested tumors were gently ground through a 70 μm nylon mesh to obtain a single-cell suspension. After incubating with ammonium chloride potassium (ACK) lysis buffer for 8 min to remove red blood cells, the cancerous cells were washed with PBS solution twice and resuspended in PBS supplemented with 2% FBS.

As for regulatory T cells staining, the tumor cells were firstly incubated with diluted APC-eFluor 780-anti-mouse CD4 and ACP-anti-mouse CD25 antibodies for 30 min at 4 °C. After washing twice with PBS, the cells were resuspended in 200 μL of intracellular fixation buffer and incubated for another 30 min at room temperature. The cells were then washed twice with permeabilization buffer and stained with 100 μL of diluted intracellular cytokines antibodies containing PE-anti-mouse Foxp3 in the darkness for 30 min. Finally, after washing with PBS, the proportion of regulatory T cells was measured by flow cytometry (BD FACS Celesta).

As for the evaluation of CD8+ T cells activation, 50 μL of diluted surface staining antibodies, including FITC-anti-mouse CD8 and PE/Cy7-anti-mouse CD69 were added in each sample and incubated with the cells for 30 min at 4 °C. After washing with PBS, the proportions of activated CD8+ T cells were determined by flow cytometry (BD FACS Celesta).

To examine other immune cell populations, tumor cells were stained with PE-anti-mouse NK1.1 (to mark NK cells), FITC-anti-mouse CD11b, PE-anti-mouse F4/80 (to mark macrophages), APC-anti-mouse CD86 (to mark M1 macrophages), PE/Cy7-anti-mouse CD206 (to mark M2 macrophages), PE-anti-mouse Ly6G, PE/Cy7-anti-mouse CD206 (to mark N2 neutrophils), then measured using a flow cytometry (BD FACS Celesta).

2.14. Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as means ± SD. All statistical analyses were performed using Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in Graphpad Prism. Levels of significant differences were expressed as follows, ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis and characterization of monomers

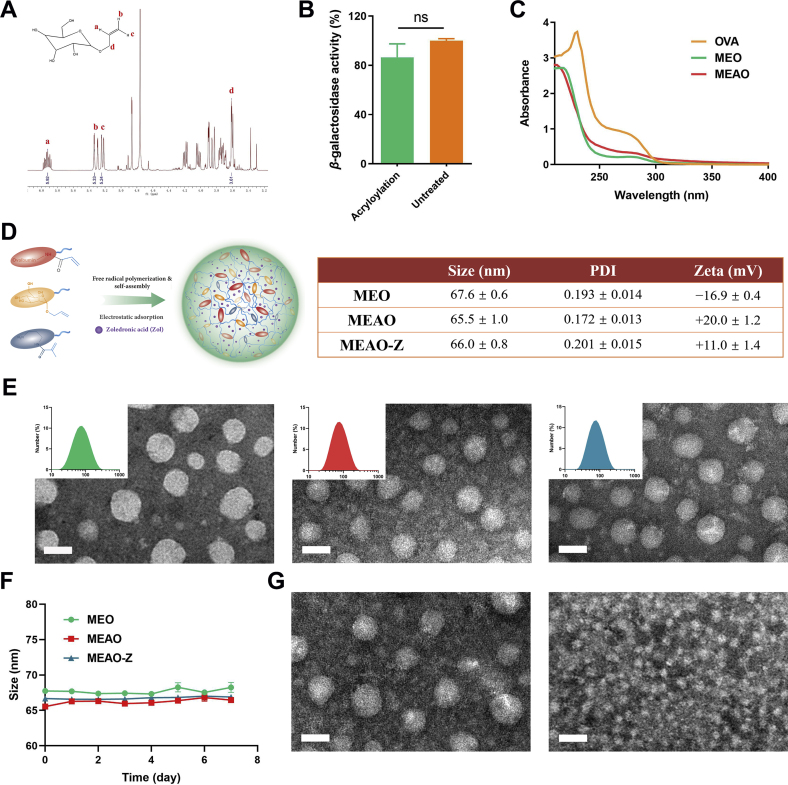

Allyl-d-mannopyranoside (mannose monomer) was synthesized as previously described and the synthetic product was characterized by 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O), δ [ppm]: 5.92 (m, 1H, Ha), 5.33 (d, 1H, Hb), 5.24 (d, 1H, Hc), 3.61 (d, 2H, Hd). The presence of these characteristic absorption peaks indicates successful modification of the double bond on mannose (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Characterization of MEO, MEAO, MEAO-Z. (A) The 1H NMR of allyl-d-mannopyranoside. δ: 5.92 (m, 1H, Ha), δ: 5.33 (d, 1H, Hb), δ: 5.24 (d, 1H, Hc), δ: 3.61 (d, 2H, Hd). (B) Effect of acryloyl modification on β-galactosidase activity. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3), ns, not significant, t-test analysis. (C) Ultraviolet absorbance of OVA, MEO, and MEAO. (D) Schematic diagram of MEAO, hydrodynamic diameter distribution and zeta potential of nanoparticles. (E) Transmission electron micrographs. Scale bar = 50 nm. (F) Stability of nanoparticles in 1 × PBS at 4 °C. (G) Acid-sensitive characteristic of MEAO investigation: transmission electron micrograph of MEAO incubated in 1 × PBS (pH = 7.4) or acetic acid (pH = 5.4) for 7 h. Scale bar = 50 nm.

Polymerizable ovalbumin was synthesized by a simple acryloyl modification on the amino groups of OVA through a mild amide reaction. Based on the characteristics that primary amine and fluorescamine can react to generate fluorescence, the modified degree of acryloyl groups on ovalbumin was calculated according to Eq. (1). The number of conjugated acryloyl groups on ovalbumin was 15. To verify whether the acryloyl modification affects the stability of protein, β-galactosidase was used as a model protein and modified with acryloyl groups under the same reaction condition to replace ovalbumin. β-galactosidase catalyzes the hydrolysis of 2-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) to produce O-nitrophenol. Therefore, the β-galactosidase activity was detected by measuring the absorption value of O-nitrophenol at 420 nm. Compared with the untreated group, the activity of acryloyl modified β-galactosidase decreased by less than 15%, indicating that acryloylation hardly affects protein stability (Fig. 2B).

3.2. Preparation and characterization of MEO, MEAO, MEAO-Z

Under anaerobic conditions, polymerizable OVA reacts with allyl-d-mannopyranoside by free radical in situ polymerization to form nanoparticles as shown in the schematic diagram (Fig. 1). The weakening of UV absorption of MEO, MEAO preliminarily indicated that OVA was involved in self-assembly and part of OVA was wrapped inside the nanoparticles (Fig. 2C). Dynamic light scattering showed a uniform size of 67.6 ± 0.6 nm and electrophoretic light scattering showed a negative zeta-potential of −16.9 ± 0.4 mV for MEO. The zeta-potential of MEAO fliped into +20.0 ± 1.2 mV after the involvement of positively charged regulator Apm, while the size of MEAO was almost unchanged. By virtue of the positive property of MEAO, zoledronic acid as an adjuvant was encapsulated via electrostatic adsorption to prepare MEAO-Z. MEAO-Z showed a hydrodynamic diameter of 66.0 ± 0.8 nm and a slightly decreased zeta-potential of +11.0 ± 1.4 mV (Fig. 2D) as compared to MEAO. The encapsulation efficiency of OVA and Zol were 84.3% and 80.1%, respectively, for MEAO-Z. Therefore, the amount of Zol was 20 μg in MEAO-Z (containing 20 μg OVA). Transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 2E) showed that all nanoparticles were spherical and monodispersed. The particle sizes observed in the images were similar to the results detected by the Nano Zetasizer. After seven consecutive days of size monitoring, these nanoparticles showed good stability in 1 × PBS at 4 °C (Fig. 2F). They also displayed a satisfactory stability in 10% FBS at 37 °C within 48 h (Supporting Information Fig. S1). Furthermore, these nanoparticles were acid-sensitive due to the presence of crosslinker EMA. As seen from the picture of transmission electron microscopy, MEAO were degraded under acidic conditions (pH = 5.4) within 7 h while could maintain integrity in neutral 1 × PBS solution (Fig. 2G). As shown in Supporting Information Fig. S2, over 60% of OVA was released from MEAO within 4 h and an almost complete release (95%) was observed at 24 h at pH 5.4. In a stark contrast, only around 40% of OVA was released from MEAO at pH 7.4 within 24 h. This is beneficial as this phenomenon indicated that the nanoparticles could be stable in the extracellular environment while promoting the intracellular release of antigens after experiencing the acidic environment of the endosome.

3.3. Cytotoxicity and cellular uptake

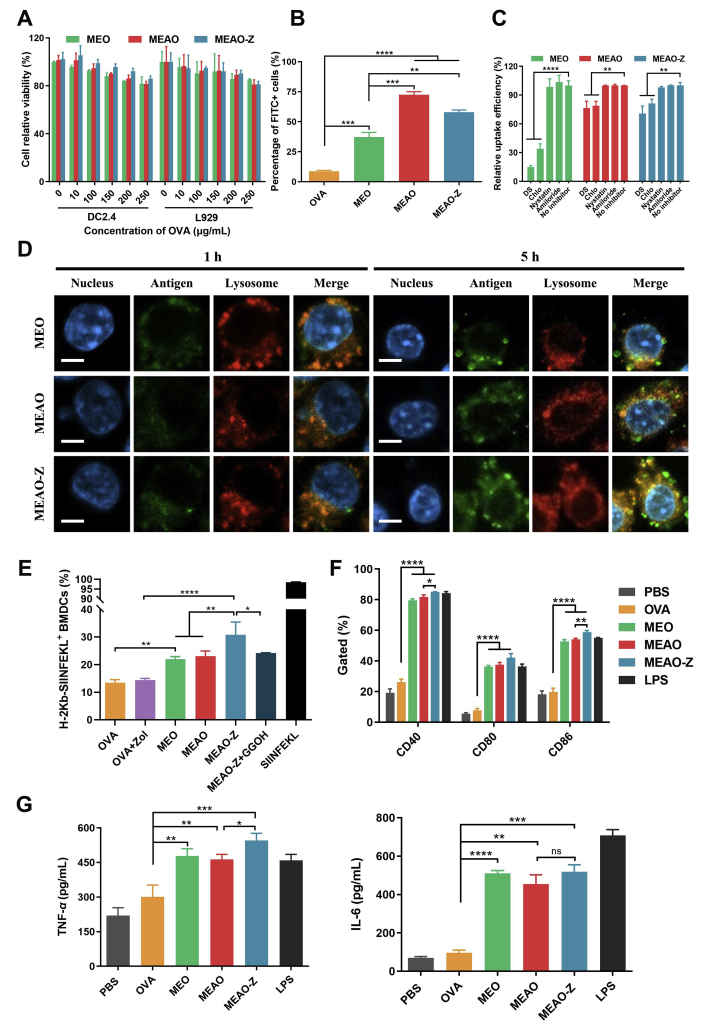

Cytotoxicity of the nanoparticles was detected by the CCK-8 assay. The nanoparticles showed slight dose-dependent cytotoxicity. Nevertheless, the viability of DC2.4 and L929 cells in all groups remained higher than 80%, indicating that our nanovaccines were relatively safe (Fig. 3A). Next, we labeled OVA with FITC dye to evaluate the internalization efficiency of the nanoparticles in DC2.4 cells (Fig. 3B). Flow cytometry results showed that MEO, MEAO, MEAO-Z significantly increased the internalization of OVA. The percentage of FITC-positive cells was less than 9% in the free-OVA treated group, while the three types of nanoparticles all exceeded 35%. In addition, the internalization efficiency of cationic nanoparticles was higher than that of negative nanoparticles. Compared with MEO, MEAO and MEAO-Z were increased by 1.95- and 1.56-fold, respectively, indicating that the electrostatic interaction between the nanoparticles and cells played an important role in the cellular uptake. In addition, the confocal microscopy images also indicated that compared with OVA group, all the synthesized nanovaccines could promote DCs internalization, which was manifested as the significantly enhanced green fluorescence inside the cells (Supporting Information Fig. S3).

Figure 3.

Uptake behavior of nanoparticles, antigen cross-presentation and maturation of BMDCs. (A) DC2.4 and L929 cells' relative viability after incubating with different concentrations of nanoparticles. (B) DC2.4 cells internalization. (C) Internalization mechanism investigation. After being pretreated with different inhibitors, the uptake efficiency of nanoparticles was detected by flow cytometer. (D) Representative confocal laser scanning images of DC2.4 cells cultured for 1 or 5 h with FITC (green) labeled MEO, MEAO, and MEAO-Z. Lysosomes were stained with LysoTracker Red (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 5 μm. (E) Cross-presentation of OVA in bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs). (F) Expression of costimulatory molecules CD40, CD80, and CD86 on BMDCs after 24 h incubation with different formulations. (G) Concentrations of TNF-α and IL-6 cytokines in the BMDCs culture supernatants. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001, ns, not significant, one-way ANOVA.

To investigate the mechanism of cellular uptake, DC2.4 cells were pretreated with different inhibitors to block specific endocytic pathways. Pretreatment of DC2.4 with dextran sulfate and chlorpromazine markedly inhibited internalization, indicating that MEO, MEAO, and MEAO-Z were internalized partly through scavenger receptor-mediated endocytosis36 and clathrin-mediated endocytosis37 (Fig. 3C). We specifically investigated whether mannosylated nanoparticles were internalized through mannose receptors-mediated endocytosis in BMDCs (Supporting Information Fig. S4). The results showed that the uptake was sharply reduced in the presence of mannose, obviously indicating that the mannose receptor was involved in the endocytosis42.

3.4. Intracellular trafficking and antigen cross-presentation assessment

Cross-presentation of exogenous antigens via the MHC-I pathway is crucial for the excitation of CD8+ T cell response for cancer immunotherapy32,43. Therefore, we next investigated the capacity of nanoparticles to escape from lysosomes and to deliver antigen into the cytosol in DC2.4 cells. Firstly, the overlapping fluorescence signal was unmistakable for OVA and lysosome after incubating cells with MEO, MEAO, and MEAO-Z for 1 h, revealing efficient internalization of the formulation. After another 4 h incubation, the separation of green fluorescence of FITC-labeled OVA and red fluorescence of LysoTracker was observed, confirming the successful escape of antigen from lysosome into the cytosol (Fig. 3D).

To further study whether MEAO-Z can promote antigen cross-presentation, BMDCs treated with nanoparticles and H-2Kb-SIINFEKL complexes on the surface of cells were examined by flow cytometry (Fig. 3E). Compared to free-OVA, MEO and MEAO increased the proportion of H-2Kb-SIINFEKL positive cells by 1.63- and 1.71-fold, respectively. Consistent with the above lysosome escape results, MEAO-Z showed the most potent ability to cross-present antigen. The proportion of H-2Kb-SIINFEKL positive cells in the MEAO-Z treated group was significantly higher than that of MEO and MEAO (P < 0.01), which suggested the presence of adjuvant Zol promoted antigen cross-presentation. However, the enhanced effect could be eliminated by supplementary geranylgeraniol (GGOH), a downstream metabolite in the mevalonate pathway, which helped to restore the geranylgeranylation process required for the synthesis of small GTPases, indicating that Zol worked by interrupting the mevalonate pathway44.

Meanwhile, the expression of costimulatory factors CD40, CD80, and CD86 on BMDCs was detected to investigate the ability of mannosylated nanoparticles to induce the maturation of BMDCs (Fig. 3F). The results showed that all three types of nanoparticles significantly upregulated the proportion of CD40, CD80, and CD86 positive cells. Compared with free-OVA, the positive proportion of the three costimulatory molecules increased by more than 2.6-fold for MEO, 2.8-fold for MEAO, and 3-fold for MEAO-Z. Additionally, all nanoparticles significantly promoted the secretion of cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 as compared to PBS and free-OVA, which was also beneficial to lymphocytes activation and polarization (Fig. 3G).

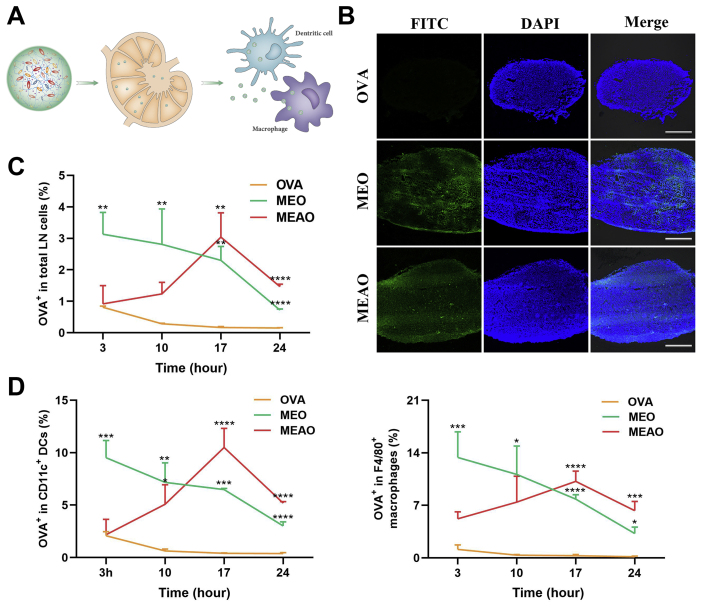

3.5. Promoted LNs transportation

Targeting lymph nodes provides the possibility to deliver antigen directly to a large number of APCs, thereby generating an effective immune activation. Hence, we investigated whether the nanovaccines can achieve effective lymph node transport. Firstly, we noticed a significant lymph node targeting effect through observation on the frozen section of lymph nodes. The fluorescent images showed that free-OVA had a limited ability to target lymph nodes and the green fluorescence of FITC-OVA was nearly invisible in the section. By contrast, MEO and MEAO could efficiently deliver antigen to lymph nodes, as significantly enhanced fluorescent brightness under the same viewing condition was observed (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Lymph nodes targeting and internalized by lymph node resident APCs. (A) Schematic diagram of nanoparticles draining to lymph nodes. (B) Confocal fluorescent images showing the distribution of OVA in inguinal lymph nodes at 14 h after administration of OVA, MEO, and MEAO. Scale bar = 200 μm. Mice were subcutaneously injected in the tail base with OVA, MEO, or MEAO containing 20 μg FITC-OVA, then inguinal lymph nodes were harvested at the desired time points. Percentage of OVA+ cells in total LN cells (C), in CD11C+ DC cells or in F4/80+ macrophages (D) by flow cytometry. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA.

To further explore the potential of mannosylated nanoparticles to be internalized by lymph node-resident cells, especially DCs and macrophages, FITC-labeled nanoparticles were subcutaneously injected into the tail base of mice. At desired time points, their ipsilateral inguinal lymph nodes were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry. Due to the proper particle sizes, MEO and MEAO could efficiently transport to draining lymph nodes, while free-OVA was more likely to enter blood capillaries rather than lymphatic vessels. Therefore, experimental results showed that MEO and MEAO significantly promoted FITC-OVA internalization in total lymph node-resident cells as compared to free FITC-OVA (Fig. 4C). The figure for MEO reached a peak within 3 h after interstitial injections, while MEAO and MEAO-Z transported to lymph node at a slower pace (Supporting Information Fig. S6). After arrival in the lymph node, MEO, MEAO and MEAO-Z could be highly internalized by DCs and macrophages (Fig. 4D) through the recognition of mannose receptors. In terms of DCs internalization, the percentages of FITC-positive at 17 h were increased by 15.95-fold in the MEO group and 25.79-fold in the MEAO group as compared to the OVA group. However, due to the intracellular process of internalized nanoparticles and clearance of wandering nanoparticles, the distribution of nanoparticles in lymph nodes would decrease after a saturated cellular uptake. Despite of this, after administration of MEO and MEAO for 24 h, the percentage of FITC-positive cells in DCs remained above 3%, while the OVA group was lower than 0.2%, which indicated that the nanovaccines could prolong the lymph nodes retention than free antigen.

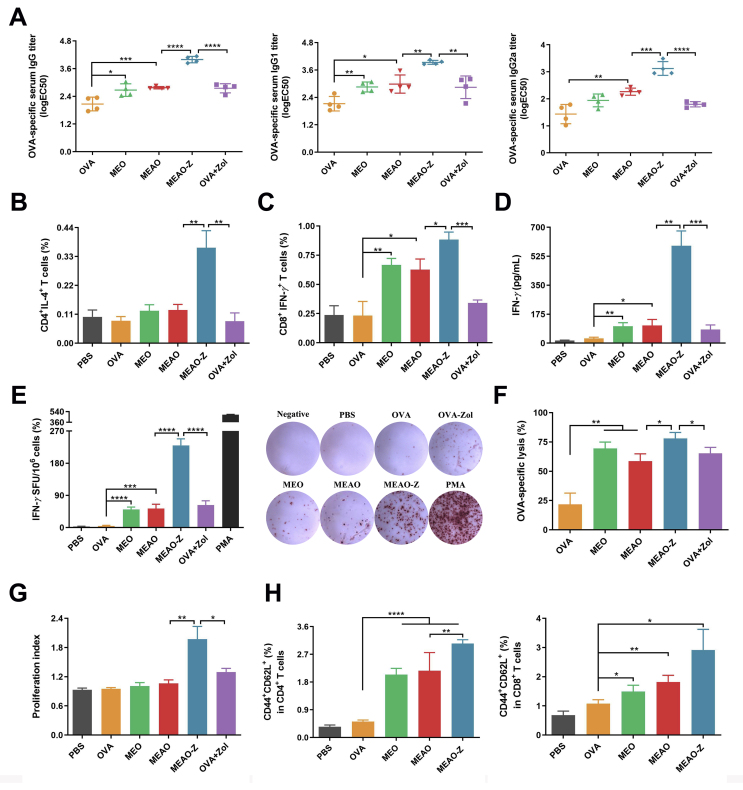

3.6. Ability of MEAO-Z to activate immune responses

Encouraged by these results in vitro, we next investigated the capacity of MEAO-Z to stimulate the antigen-specific immune response. On Days 0, 7, and 14, C57BL/6 female mice were immunized subcutaneously with different vaccine formulations. First, a blood routine examination was performed to investigate the systemic toxicity of our nanovaccines (Supporting Information Fig. S7). The results showed that all nano-formulations did not cause abnormal fluctuations compared with the PBS-treated group. Afterward, we detected the OVA-specific antibody titers in serum to evaluate the humoral immunity. The results demonstrated that all nanovaccines had induced significantly stronger antibody responses than free-OVA. MEAO-Z elicited the highest IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a serum antibody titers in all groups (Fig. 5A), suggesting that co-delivery antigen and adjuvant with our self-assembled nanoparticles can effectively stimulate humoral immune responses.

Figure 5.

Ability of MEAO-Z to activate immune responses. (A) Levels of OVA-specific serum IgG, IgG1, IgG2a antibodies titer of vaccinated mice. (B, C) Percentage of IL-4+CD4+ T cells and IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells in splenocytes. (D) Concentration of IFN-γ in the culture supernatant of splenocytes stimulated with SIINFEKL peptide and OVA. (E) Numbers of IFN-γ secreting splenocytes were measured using ELISPOT assay. Phorbol ester (PMA) was used as a positive control. (F) OVA-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes response was evaluated using a CFSE labeling method and detected by flow cytometry. (G) Proliferation index of splenocytes after incubating with antigen for 72 h. (H) Percentage of effector memory T cells in splenocytes harvested from immunized mice. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 to 4), ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA.

We next harvested splenocytes of the vaccinated mice to evaluate T cell immune responses induced by MEAO-Z. After ex vivo culture and restimulation, MEAO-Z represented the highest percentage of IL-4 secreting CD4+ T cells and IFN-γ secreting CD8+ T cells, indicating that MEAO-Z efficiently motivated both humoral and cellular immune responses (Fig. 5B and C). These results showed a similar trend as that observed in the antibody response study. IFN-γ, a pleiotropic cytokine secreted by CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, stimulates the proliferation and activation of NK cells and cytotoxic T cells, which is crucial for anti-tumoral immune response45. Therefore, we next measured the concrete production of cytokine IFN-γ in the supernatant using ELISA assay (Fig. 5D) and ELISPOT assay (Fig. 5E). Compared with the OVA + Zol and MEAO group, MEAO-Z increased the concentration of IFN-γ in the supernatant by 7.16- and 5.52-fold, respectively. MEAO-Z group had the largest number of IFN-γ spots, with 230 spots per 1 × 106 T lymphocytes from the spleen, which was 3.65-fold than OVA + Zol and 4.33-fold than MEAO. These results showed a similar trend that MEAO-Z stimulated the highest IFN-γ secretion than all other formulations, confirming the potential of MEAO-Z to elicit a robust cell-mediated adaptive immune response.

Due to the above findings that MEAO-Z could induce an effector phenotype in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, we further evaluated the activity of cytotoxic T lymphocytes induced by MEAO-Z. SIINFEKL, as an epitope of OVA, was incubated with splenocytes from naïve mice to prepare target cells that can be killed by OVA-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Splenocytes incubated with blank medium were performed as an internal parameter to eliminate the interference of normal apoptosis. The percentage of target cells lysis was calculated based on the ratio of CFSElow/high. MEAO-Z led to a significantly higher percentage of target cell lysis, which was 3.58-fold higher than OVA, 1.33-fold than MEAO, and 1.2-fold than OVA + Zol (Fig. 5F). Our results showed that MEAO-Z had great potential in eliminating cancerous cells due to its superior cytotoxic T cells response.

As reported, immune cells will rapidly proliferate and differentiate to induce an adequate response when the vaccinated body was stimulated by the antigen again. Therefore, we detected the proliferation index of splenocytes after antigen restimulation to evaluate the effectiveness of the nanovaccines. The experimental result showed MEAO-Z induced the highest cellular proliferation, indicating MEAO-Z elicited the strongest immune response (Fig. 5G).

Establishing long-term immunological memory is the ultimate goal of vaccination. The immune system can quickly respond to the invading pathogens and generate robust effects to avert the occurrence and exacerbation of diseases. Here, we evaluated the proportions of effector memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in splenocytes harvested from vaccinated mice (Fig. 5H). Mice immunized with MEAO-Z owed the highest proportion of CD44+CD62L+ cells in both CD4+ and CD8+T cells, which suggested MEAO-Z efficiently produced a central immune memory and could provide long-term protection.

3.7. MEAO-Z inhibited tumor growth and prolonged survival

Our findings indicated that MEAO-Z had elicited a strong cell-mediated immune response, including higher IFN-γ+ T cell percentage, IFN-γ secretion level, and antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity, which inspired us to explore the ability of MEAO-Z to inhibit tumorigenesis. As shown in the tumor growth curves (Fig. 6B), MEO and MEAO had a significantly stronger anti-tumor effect as compared to the free-OVA group (P < 0.0001). MEAO-Z showed the strongest inhibitory effect on tumor growth. On Day 16, the tumor volume in the MEAO-Z group was less than 200 mm3, while the MEO and MEAO groups both exceeded 750 mm3. The tumor volume of some mice in the PBS, OVA, and OVA + Zol groups had exceeded 2000 mm3, and the mice began to die. The mice survival experiments showed a similar trend. As shown in Fig. 6C, the median survival time of free-OVA treated mice was limited to 18 days, while the MEO and MEAO had a certain prolongation effect to 22 days. Importantly, MEAO-Z showed the strongest ability to prolong mice survival. The median survival time in MEAO-Z group was 30 days, which was 12, 10, 8, and 8 days longer than OVA, OVA + Zol, MEO, and MEAO, respectively. These data together showed that MEAO-Z can significantly slow the growth of EG7-OVA lymphoma and prolong the survival of tumor burden mice.

Figure 6.

MEAO-Z inhibit tumor growth and prolong survival. (A) Schematic of the therapeutic vaccination schedule. (B) Tumor volume growth curves and (C) percent survival of EG7-OVA lymphoma bearing mice (n = 9). (D–I) Immune cell populations in tumor microenvironment. (D) Representative contour plots of the frequency of Foxp3+CD25+ cells among CD4+ T cells in tumors. Frequency of (E) regulatory T cells, (F) activated CD8+ T cells, (G) natural killer cells, (H) anti-tumor effector M1-like macrophages and pro-tumor effector M2-like macrophages, (I) pro-tumor effector N2-like neutrophils in tumor (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SD, ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

In addition, we also verified the anti-tumor effects of MEAO-Z in a prophylactic tumor model. As shown in the tumor growth curves (Supporting Information Fig. S9B), the average tumor volume in the PBS group was 1889.7 mm3 on Day 15, nearly three times as large as MEAO-Z which was less than 650 mm3. MEAO-Z group also showed the best capacity in prolonging survival of tumor-bearing mice (Fig. S9C). The median survivals of PBS and OVA groups were both only 19 days, while MEO and MEAO extended to 23 and 27 days, respectively. Importantly, MEAO-Z immunized mice had the longest median survival to 29 days. In sum, the results of tumor volume and survival time in a prophylactic tumor model supported the superior immune responses of the MEAO-Z group.

3.8. MEAO-Z reprogrammed immune activity in the tumor microenvironment

After seeing that MEAO-Z possessed a superior cancer therapeutic effect, we further investigated the immune activation capacity of our formulations in tumors. We firstly detected the proportion of regulatory T cells (Foxp3+CD25+CD4+ T cells) in tumors (Fig. 6D), which can promote effector T cells exhaustion and induce immunosuppression in tumors46, 47, 48. Saline group showed a highest Treg percentage exceeding 3.5%, and slightly decreased the percentage to around 3.0% after the injection of free-OVA. By contrast, the administration of three nanovaccines successfully lowered the Treg proportions. Specifically, MEAO-Z showed the best modulation capacity: compared with saline, free OVA, and OVA + Zol groups, MEAO-Z down-regulated the percentage of Treg cells by 3.6-, 3.2-, and 2.74-folds, respectively (Fig. 6E). We next investigated the percentages of M2-like macrophages49, 50, 51 and N2-like neutrophils52,53, which can also promote angiogenesis and tumor invasion. Our findings showed that compared with the untreated group, MEAO-Z could significantly turn down the proportion of M2 macrophages by 1.59-fold to 46.2% (Fig. 6H). The percentage of N2 neutrophils for MEAO-Z was 69.3%, which was 14.6%, 11.3%, and 17.3% lower than the saline, free OVA, and OVA + Zol groups, respectively (Fig. 6I). The above results showed that MEAO-Z relieved the immunosuppression in tumors microenvironment. Meanwhile, we also investigated the level of CD8+ T cells54,55 and natural killer cells (NK cells)56,57 which play crucial roles in the killing of cancerous cells. We found that the MEAO-Z treatment group had the highest level of CD8+T cell activation (Fig. 6F) and NK cells (Fig. 6G) in tumors. Compared with the saline, free OVA, and OVA + Zol groups, the proportions of activated CD8+ T cells in MEAO-Z group were up-regulated by 13.2%, 13.0%, and 11.4%, respectively. In addition, mice treated with MEAO-Z had a higher proportion of M1 macrophages in tumors51,58, which was significantly increased by 1.76-, 1.54-, and 1.92-fold when compared with the saline, free OVA, and OVA + Zol groups, respectively (Fig. 6H). Overall, the above results showed that MEAO-Z could effectively regulate immune states, reverse the dilemmas of immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment, and significantly improve the anti-tumor effect.

4. Discussion

Immunotherapy has evolved to become another momentous pillar for cancer treatment by exciting the immune system to fight off cancerous cells. The therapeutic effect is controlled by the intensity of cancer-specific cellular immune responses. Under this circumstance, nanovaccines opened new horizons to initiate and intensify immune responses. However, conventional nanovaccines normally involve the use of exterior carrier material, which brings complicated fabrication issues and a series of potential side effects. To address these challenges, we herein developed an “antigen carries antigen” strategy by generating simple in situ self-assembly of antigen, through which particles at the precision nanoscale can be yielded. The nanoform delivery of free antigen was easily achieved without the assistance of exterior carriers. Different from the previous self-assembling methods, we activated the polymerizability of the model antigen OVA by simple acrylate modification. Our results showed that the applied radical reaction strategy was mild in preparation conditions, short in time, and green in used reagents, which did not affect the stability or immunogenicity of the antigen. Finally, the antigen self-assembled nanoparticles showed effective lymph node targeting and prolonged lymph node retention (Fig. 4B–D, and Fig. S6).

To elicit potent CD8+ T cell responses, sufficient cytoplasm delivery of exogenous antigens in DCs is required. In our current study, we applied several strategies to reach this goal. Firstly, MEAO-Z with a diameter of 70 nm was prepared by controlling the proportion of monomers input, which could be preferably drained to lymph nodes. Secondly, mannose monomer was used as a ligand for improving DCs’ targeting and internalization. Thirdly, research shows that the rate of particles degradation and antigen release will influence the effect of antigen presentation, and the rapidly degraded nanovaccines have more efficient MHC-I presentation59. Therefore, an acid-sensitive crosslinking agent was used to accelerate the degradation of MEAO-Z and the release of OVA in the first step of intracellular processing. On the other hand, if the released antigen does not escape from the lysosome timely, it may be degraded by lysosome located protease, resulting in the loss of antigen activity. This challenge was addressed from two aspects. From the time dimension, Zol used as an adjuvant can delay lysosome maturation, alleviating the acidification and protease activity in the lysosomes. Therefore, the antigen was protected from excessive degradation. From the space dimension, the disintegration of the crosslinking agent in the self-assembled nanoparticles is often accompanied by the swelling effect of nanoparticles, which could contribute to the destruction of lysosomal membrane structure and promotion of intracytoplasmic release60. Meanwhile, the positively charged Apm in MEAO-Z could generate proton sponge effects which contributed to lysosome burst for enhancing antigen release into the cytoplasm61. Consequently, the swelling effect of nanoparticles and the proton sponge effect jointly promoted lysosomal escape and cytosolic diversion. As a result, OVA could be effectively cross-presented via a cytosolic pathway as demonstrated by the expression of H-2Kb-SIINFEKL (Fig. 3E). As expected, MEAO-Z showed the strongest ability of antigen cross-presentation, which is critical to the activation of CD8+ T cell responses (Fig. 5F) for cancer cells killing. Finally, in a mouse EG7-OVA model, MEAO-Z showed significant tumor-suppressive effects and prolonging of mice survival (Fig. 6B and C, Figs. S9B and S9C).

In the absence of additional nano-structed materials, MEAO-Z also achieved the efficient codelivery of antigen and adjuvant to DCs. Through this self-assembly strategy initiated by free radical reactions, nanoparticles can become more functional by introducing other monomers, just as the positively charged monomer enhanced the diversity of drug loading, the mannose monomer was conducive to the uptake of DCs in MEAO-Z. In fact, this strategy is not limited to vaccine delivery, but can also be customized to treat a variety of diseases by loading different protein drugs and selecting different crosslinking agents. For example, an alkali-responsive crosslinking agent was used to release bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) to enhance bone regeneration24. Crosslinkers contain disulfide bonds can be redox-responsive to release the active caspase 3 (CP-3) to induce apoptosis in cancerous cells62. In the current study, an acid-responsive crosslinking agent was used in MEAO-Z, which can protect the antigen from degradation by extracellular proteases. Antigen activity is hidden until MEAO-Z reaches the acid lysosomes, providing a strong guarantee for generating effective immunity.

Finally, MEAO-Z has a good potential for large-scale industrialization. Nanoparticles fabricated with additional excipients sometimes are difficult to scale up due to the complicated synthesis process and elaborate experimental operations. However, there are no fine requirements for all operations in the preparation of MEAO-Z. Without the need for overheating or overcooling temperature control, MEAO-Z can be prepared at room temperature by simple stirring in a short time. Since strong acid, strong bases, irritating organic solvents, etc., are not used, the antigenicity of antigens is not compromised during the preparation. In addition, with more accurate inputs and easier adjustment of component ratios in a scale reaction system, it is possible to prepare highly controllable nanoparticles. We will further optimize the production methods of reactive oxygen species or free radicals, and continue to strive for clinical translation.

5. Conclusions

Integrating pharmaceutical engineering technology with nanotechnology has become a promising trend to exploit robust cancer vaccines. In this study, we have developed a self-assembled nanovaccine constituted from mannosylated antigen and investigated their cancer immunotherapy potency. Our results showed that the mannose-modified, adjuvant co-loaded nanovaccine with a high antigen density showed remarkable profiles in LNs transportation, DCs internalization, and antigen cross-presentation. The system triggered effective humoral and cellular immunity, especially a CTL response for inhibiting tumor growth. These results highlighted that the antigen self-assembled nanovaccine platform might be a promising cancer immunotherapy strategy with better therapeutic efficacy and clinical translation potential.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81925036 & 81872814), the Key Research and Development Program of Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (2020YFS0570, China), Sichuan Veterinary Medicine and Drug Innovation Group of China Agricultural Research System (CARS-SVDIP), 111 project (b18035, China) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (China).

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.03.017.

Author contributions

Xun Sun initiated and supervised the research. Yunting Zhang carried out the experiments and performed data analysis. Min Jiang carried out the experiments and wrote the manuscript. Xun Sun, Guangsheng Du and Ming Qin revised the manuscript. Xiaofang Zhong, Chunting He, Yingying Hou, and Rong Liu participated part of the experiments. All of the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Adams S. Toll-like receptor agonists in cancer therapy. Immunotherapy. 2009;1:949–964. doi: 10.2217/imt.09.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn S., Lee I.H., Kang S., Kim D., Choi M., Saw P.E., et al. Gold nanoparticles displaying tumor-associated self-antigens as a potential vaccine for cancer immunotherapy. Adv Healthc Mater. 2014;3:1194–1199. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201300597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Temizoz B., Kuroda E., Ishii K.J. Vaccine adjuvants as potential cancer immunotherapeutics. Int Immunol. 2016;28:329–338. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxw015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finck A., Gill S.I., June C.H. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age and looks for maturity. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3325. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17140-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu G., Zhang F., Ni Q., Niu G., Chen X. Efficient nanovaccine delivery in cancer immunotherapy. ACS Nano. 2017;11:2387–2392. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b00978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong X., Zhong X., Du G., Hou Y., Zhang Y., Zhang Z., et al. The pore size of mesoporous silica nanoparticles regulates their antigen delivery efficiency. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaaz4462. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz4462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhong X., Zhang Y., Tan L., Zheng T., Hou Y., Hong X., et al. An aluminum adjuvant-integrated nano-MOF as antigen delivery system to induce strong humoral and cellular immune responses. J Control Release. 2019;300:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luo M., Wang H., Wang Z., Cai H., Lu Z., Li Y., et al. A STING-activating nanovaccine for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Nanotechnol. 2017;12:648–654. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2017.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y., Fang F., Li L., Zhang J. Self-assembled organic nanomaterials for drug delivery, bioimaging, and cancer therapy. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2020;6:4816–4833. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c00883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao H., Guo Y., Liu H., Liu Y., Wang Y., Li C., et al. Structure-based design of charge-conversional drug self-delivery systems for better targeted cancer therapy. Biomaterials. 2020;232:119701. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Umair M., Javed I., Rehman M., Madni A., Javeed A., Ghafoor A., et al. Nanotoxicity of inert materials: the case of gold, silver and iron. J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci. 2016;19:161–180. doi: 10.18433/J31021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Jong W.H., Borm P.J. Drug delivery and nanoparticles: applications and hazards. Int J Nanomed. 2008;3:133–149. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knudsen K.B., Northeved H., Kumar P.E., Permin A., Gjetting T., Andresen T.L., et al. In vivo toxicity of cationic micelles and liposomes. Nanomedicine. 2015;11:467–477. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan J., Wang Y., Zhang C., Wang X., Wang H., Wang J., et al. Antigen-directed fabrication of a multifunctional nanovaccine with ultrahigh antigen loading efficiency for tumor photothermal-immunotherapy. Adv Mater. 2018;30:1704408. doi: 10.1002/adma.201704408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang T.Z., Stadmiller S.S., Staskevicius E., Champion J.A. Effects of ovalbumin protein nanoparticle vaccine size and coating on dendritic cell processing. Biomater Sci. 2017;5:223–233. doi: 10.1039/c6bm00500d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang K., Wen S., He L., Li A., Li Y., Dong H., et al. “Minimalist” nanovaccine constituted from near whole antigen for cancer immunotherapy. ACS Nano. 2018;12:6398–6409. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b00558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong X., Liang J., Yang A., Qian Z., Kong D., Lv F. A visible codelivery nanovaccine of antigen and adjuvant with self-carrier for cancer immunotherapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11:4876–4888. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b20364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiu L., Valente M., Dolen Y., Jager E., Beest M.T., Zheng L., et al. Endolysosomal-escape nanovaccines through adjuvant-induced tumor antigen assembly for enhanced effector CD8+ T cell activation. Small. 2018;14 doi: 10.1002/smll.201703539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiu Y.C., Gammon J.M., Andorko J.I., Tostanoski L.H., Jewell C.M. Modular vaccine design using carrier-free capsules assembled from polyionic immune signals. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2015;1:1200–1205. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qin M., Li M., Song G., Yang C., Wu P., Dai W., et al. Boosting innate and adaptive antitumor immunity via a biocompatible and carrier-free nanovaccine engineered by the bisphosphonates-metal coordination. Nano Today. 2021;37:101097. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan M., Du J., Gu Z., Liang M., Hu Y., Zhang W., et al. A novel intracellular protein delivery platform based on single-protein nanocapsules. Nat Nanotechnol. 2010;5:48–53. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu C., Wen J., Meng Y., Zhang K., Zhu J., Ren Y., et al. Efficient delivery of therapeutic miRNA nanocapsules for tumor suppression. Adv Mater. 2015;27:292–297. doi: 10.1002/adma.201403387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao P., Yin W., Wu A., Tang Y., Wang J., Pan Z., et al. Dual-targeting to cancer cells and M2 macrophages via biomimetic delivery of mannosylated albumin nanoparticles for drug-resistant cancer therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2017;27:1700403. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tian H., Du J., Wen J., Liu Y., Montgomery S.R., Scott T.P., et al. Growth-factor nanocapsules that enable tunable controlled release for bone regeneration. ACS Nano. 2016;10:7362–7369. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisenbarth S.C. Dendritic cell subsets in T cell programming: location dictates function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:89–103. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0088-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wculek S.K., Cueto F.J., Mujal A.M., Melero I., Krummel M.F., Sancho D. Dendritic cells in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:7–24. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0210-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keler T., Ramakrishna V., Fanger M.W. Mannose receptor-targeted vaccines. Expet Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:1953–1962. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.12.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Apostolopoulos V., McKenzie I.F. Role of the mannose receptor in the immune response. Curr Mol Med. 2001;1:469–474. doi: 10.2174/1566524013363645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Dinther D., Stolk D.A., van de Ven R., van Kooyk Y., de Gruijl T.D., den Haan J.M.M. Targeting C-type lectin receptors: a high-carbohydrate diet for dendritic cells to improve cancer vaccines. J Leukoc Biol. 2017;102:1017–1034. doi: 10.1189/jlb.5MR0217-059RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang X.J., Wang H.Y., Peng H.G., Chen B.F., Zhang W.Y., Wu A.H., et al. Codelivery of dihydroartemisinin and doxorubicin in mannosylated liposomes for drug-resistant colon cancer therapy. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2017;38:885–896. doi: 10.1038/aps.2017.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui L., Cohen J.A., Broaders K.E., Beaudette T.T., Fréchet J.M.J. Mannosylated dextran nanoparticles: a pH-sensitive system engineered for immunomodulation through mannose targeting. Bioconjugate Chem. 2011;22:949–957. doi: 10.1021/bc100596w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joffre O.P., Segura E., Savina A., Amigorena S. Cross-presentation by dendritic cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:557–569. doi: 10.1038/nri3254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xia Y., Xie Y., Yu Z., Xiao H., Jiang G., Zhou X., et al. The mevalonate pathway is a druggable target for vaccine adjuvant discovery. Cell. 2018;175:1059–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zang X., Zhang X., Hu H., Qiao M., Zhao X., Deng Y., et al. Targeted delivery of zoledronate to tumor-associated macrophages for cancer immunotherapy. Mol Pharm. 2019;16:2249–2258. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.9b00261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee R.T., Lee Y.C. Synthesis of 3-(2-aminoethylthio)propyl glycosides. Carbohydr Res. 1974;37:193–201. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)87074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang H., Wang Q., Li L., Zeng Q., Li H., Gong T., et al. Turning the old adjuvant from gel to nanoparticles to amplify CD8+ T cell responses. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2017;5:1700426. doi: 10.1002/advs.201700426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lacy M.M., Ma R., Ravindra N.G., Berro J. Molecular mechanisms of force production in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. FEBS Lett. 2018;592:3586–3605. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nabi I.R., Le P.U. Caveolae/raft-dependent endocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:673–677. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koivusalo M., Welch C., Hayashi H., Scott C.C., Kim M., Alexander T., et al. Amiloride inhibits macropinocytosis by lowering submembranous pH and preventing Rac1 and Cdc42 signaling. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:547–563. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rafiq K., Bergtold A., Clynes R. Immune complex-mediated antigen presentation induces tumor immunity. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:71–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI15640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stevens T.L., Bossie A., Sanders V.M., Fernandez-Botran R., Coffman R.L., Mosmann T.R., et al. Regulation of antibody isotype secretion by subsets of antigen-specific helper T cells. Nature. 1988;334:255–258. doi: 10.1038/334255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gonzalez P.S., O'Prey J., Cardaci S., Barthet V.J.A., Sakamaki J.I., Beaumatin F., et al. Mannose impairs tumour growth and enhances chemotherapy. Nature. 2018;563:719–723. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0729-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nunes-Hasler P., Maschalidi S., Lippens C., Castelbou C., Bouvet S., Guido D., et al. STIM1 promotes migration, phagosomal maturation and antigen cross-presentation in dendritic cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1852. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01600-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raikkonen J., Monkkonen H., Auriola S., Monkkonen J. Mevalonate pathway intermediates downregulate zoledronic acid-induced isopentenyl pyrophosphate and ATP analog formation in human breast cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:777–783. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sokolovska A., Hem S.L., HogenEsch H. Activation of dendritic cells and induction of CD4+ T cell differentiation by aluminum-containing adjuvants. Vaccine. 2007;25:4575–4585. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sawant D.V., Yano H., Chikina M., Zhang Q., Liao M., Liu C., et al. Adaptive plasticity of IL-10+ and IL-35+ Treg cells cooperatively promotes tumor T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:724–735. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0346-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marangoni F., Zhakyp A., Corsini M., Geels S.N., Carrizosa E., Thelen M., et al. Expansion of tumor-associated Treg cells upon disruption of a CTLA-4-dependent feedback loop. Cell. 2021;184:3998–4015. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khatwani N., Turk M.J. Oncogenes feed Treg cells without calling CD8s to the table. Immunity. 2020;53:13–15. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheng Y., Zhu Y., Xu J., Yang M., Chen P., Xu W., et al. PKN2 in colon cancer cells inhibits M2 phenotype polarization of tumor-associated macrophages via regulating DUSP6-Erk1/2 pathway. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:13. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0747-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yeung O.W., Lo C.M., Ling C.C., Qi X., Geng W., Li C.X., et al. Alternatively activated (M2) macrophages promote tumour growth and invasiveness in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2015;62:607–616. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xia Y., Rao L., Yao H., Wang Z., Ning P., Chen X. Engineering macrophages for cancer immunotherapy and drug delivery. Adv Mater. 2020;32 doi: 10.1002/adma.202002054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tyagi A., Sharma S., Wu K., Wu S.Y., Xing F., Liu Y., et al. Nicotine promotes breast cancer metastasis by stimulating N2 neutrophils and generating pre-metastatic niche in lung. Nat Commun. 2021;12:474. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20733-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 53.Cai B., Lin D., Li Y., Wang L., Xie J., Dai T., et al. N2-polarized neutrophils guide bone mesenchymal stem cell recruitment and initiate bone regeneration: a missing piece of the bone regeneration puzzle. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2021;8 doi: 10.1002/advs.202100584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reina-Campos M., Scharping N.E., Goldrath A.W. CD8+ T cell metabolism in infection and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:718–738. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00537-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henning A.N., Roychoudhuri R., Restifo N.P. Epigenetic control of CD8+ T cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:340–356. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shimasaki N., Jain A., Campana D. NK cells for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19:200–218. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]