Abstract

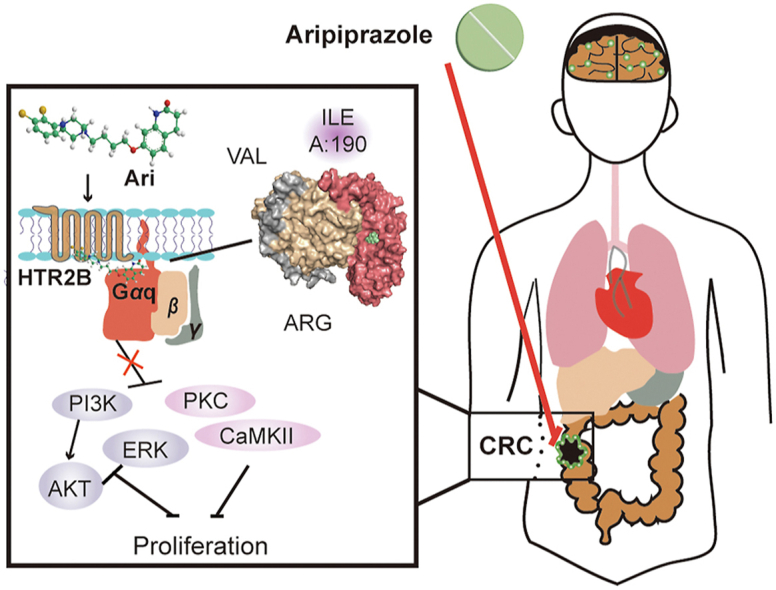

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a type of malignant tumor that seriously threatens human health and life, and its treatment has always been a difficulty and hotspot in research. Herein, this study for the first time reports that antipsychotic aripiprazole (Ari) against the proliferation of CRC cells both in vitro and in vivo, but with less damage in normal colon cells. Mechanistically, the results showed that 5-hydroxytryptamine 2B receptor (HTR2B) and its coupling protein G protein subunit alpha q (Gαq) were highly distributed in CRC cells. Ari had a strong affinity with HTR2B and inhibited HTR2B downstream signaling. Blockade of HTR2B signaling suppressed the growth of CRC cells, but HTR2B was not found to have independent anticancer activity. Interestingly, the binding of Gαq to HTR2B was decreased after Ari treatment. Knockdown of Gαq not only restricted CRC cell growth, but also directly affected the anti-CRC efficacy of Ari. Moreover, an interaction between Ari and Gαq was found in that the mutation at amino acid 190 of Gαq reduced the efficacy of Ari. Thus, these results confirm that Gαq coupled to HTR2B was a potential target of Ari in mediating CRC proliferation. Collectively, this study provides a novel effective strategy for CRC therapy and favorable evidence for promoting Ari as an anticancer agent.

Key words: Aripiprazole, 5-Hydroxytryptamine receptor, 5-Hydroxytryptamine 2B receptor, G protein subunit alpha q, Colorectal cancer, Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/the serine threonine kinase AKT, Extracellular regulated protein kinases

Graphical abstract

The antipsychotic drug aripiprazole (Ari) inhibits the proliferation of colorectal cancer cells by targeting Gαq coupled HTR2B.

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a kind of malignant tumor that occurs in the internal gastrointestinal tract and threatens human health and life1. Although significant progress has been made in targeted therapy for CRC, there are still many patients whose mutated genotypes leave them with few therapeutic options. For example, kirsten ratsarcoma viral oncogene homolog/B-Raf proto-oncogene (KRAS/BRAF) is one of the common gene mutation sites in CRC2,3. These mutations increase the malignancy of CRC and reduce patient's survival and the efficacy of traditional chemotherapy agents4,5.

Many 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors (5-HTRs) in the gastrointestinal tract accept ligands and activate multiple intracellular signaling networks to regulate the biological functions of cells. This physiological environment might bring new opportunities for CRC treatment. 5-Hydroxytryptamine receptor 1 (HTR1) and 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2 (HTR2) are closely associated with cancer cell activity6. On the one hand, current studies confirmed that 5-HT promoted CRC proliferation, primarily through HTR1D, HTR1B, and HTR1F7. On the other hand, some studies suggested that the blocking HTR1 or reducing its abundance was beneficial in preventing cancer progression8. Unlike the Gi/o protein coupled HTR1, 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2B (HTR2B) is G protein subunit alpha q (Gαq)-coupled G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR)9, and studies suggested that the pathophysiological functions of HTR2B were tissue-specific. It was known that HTR2B could mediate microglial phagocytosis and migration in the central nervous system10. Furthermore, the absence of HTR2B in pancreatic cancer cells could inhibit the proliferation of xenografts11. Blocking HTR2B could enhance the growth of hepatic parenchyma cells12. Although HTR2B is widely distributed in CRC, the relationship between HTR2B and CRC progression has yet to fully elucidate and whether HTR2B can be considered an effective anti-CRC target has not been investigated.

In recent years, antipsychotics that modulate dopamine D2 receptor (D2R) and 5-HTRs have potential anticancer activities13, 14, 15, and several epidemiological studies have shown lower rates of prostate and colorectal cancer in patients with schizophrenia who receive antipsychotics medications16,17. At present, first-generation antipsychotics, such as pentafluridol and thioridazine, exhibit surprising anticancer effects on malignant tumors, and it is suggested that the D2R might be the key target for antipsychotics against cancer18, 19, 20. Aripiprazole (Ari) is a representative drug of third-generation antipsychotics with remarkable regulatory ability to modulate the 5-HTR. In particular, Ari has a strong affinity for HTR2B but has no antagonistic effect on D2R21,22. Given that Ari still appears anticancer potency23, there must be a more critical target than D2R with the anticancer effects of antipsychotics. However, there are no published reports on the underlying anticancer mechanism of Ari through 5-HTRs yet. Considering the unique physiological environment of CRC mentioned above, this study intends to investigate the anti-CRC potential and underlying mechanisms of Ari to enrich the knowledge of antipsychotics in cancer treatment and explore novel treatment strategies for CRC.

Herein, this study verified the anti-CRC effects of Ari both in vitro and in the xenograft models, identified the function of HTR2B in CRC. Moreover, the target and underlying pharmacological mechanisms of Ari against CRC were also revealed.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents and antibodies

Aripiprazole was obtained from Meilun (Dalian, China). Brexpiprazole was obtained from Bidepharm (Shanghai, China). Cariprazine was obtained from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). Olanzapine was obtained from Adamas beta (Titan, China). Medium and Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Gibco (ThermoFisher, Waltham, USA). 5-HT was purchased from Macklin (Shanghai, China). SB 204741 was obtained from Abcam (Abcam, UK). BsbI was purchased from NEB (Ipswich, MA, USA). NheI, BamHI, and XhoI were purchased from ThermoFisher (Waltham, MA, USA). Lipo6000 Transfection Reagent, RIPA lysis buffer, protein phosphatase inhibitors, and protein loading buffer were purchased from Beyotime (Shanghai, China). SureBeads Protein G Magnetic Beads were purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA). CMC-Na was purchased from KeLong (Chengdu, China). DMSO was obtained from Dingguo (Guangzhou, China). Cetuximab was purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Methylthiazolyldiphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) was purchased from Adamas beta (Titan, China). CCK8 was purchased from Bioground (Chongqin, China). TRIzol reagent was purchased from Accurate (Hunan, China). RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit was purchased from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, USA). Master qPCR Mix was purchased from TSINGKE (Beijing, China). PVDF membrane was purchased from Millipore (Merck, Germany). SP Kit (Broad Spectrum) and Hematoxylin–Eosin (HE) Stain Kit were purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China). Primary antibody p-85 was purchased from Servicebio (Wuhan, China). Primary antibody p-mTOR (Ser2448) was purchased from Santa (Santa Cruz, USA). Primary antibody mTOR was purchased from Huabio (Hangzhou, China). Primary antibodies p-AKT (Ser473) and AKT were purchased from Proteintech (Wuhan, China). Primary antibodies p-ERK1/2 (T202/Y204, T185/Y187), ERK1/2, and Gαq were purchased from ABclonal (Wuhan, China). Primary antibody HTR2B was purchased from Immunoway (Suzhou, China). Secondary antibody and primary antibody of GAPDH were purchased from Servicebio (Wuhan, China). Primary antibody Tubulin and Ki67 was purchased from Beyotime (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Plasmids

For Gαq and HTR2B knockdown, sgRNA was inserted into the BsbI site of PX459 V2.0+K848A and sequence-verified by Tsingke sequencing. For Gαq over-expression, the entire CDS region of Gαq was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), inserted into sites of pCDH-CMV, and sequence-verified by Tsingke sequencing. Gαq mutant plasmid was obtained by PCR using the mutant primers, and pCDH-CMV-Gαq was used as a template. In order to improve the knockout transfection efficiency, two sgRNAs were designed in exon 1 and exon 2 regions close to the translation start site. The sgRNA, primer sequences, and genomic locations are described in Supporting Information Table S1.

2.3. Cell culture and transfection

FHC, HCT116, HT29, LOVO, SW480, A549, and HeLa cells were obtained from laboratory storage and purchased from National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (Shanghai, China). HT29 cells were cultured with Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium, and other cells were cultured with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum medium. All cells were cultured in a humidified environment with 5% carbon dioxide at 37 °C, and cells were passaged every two days. Transfection was performed at a cell density of 60%–70%, using Lipo 6000 Transfection Reagent (Beyotime) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fresh media was replaced at 24 h post-transfection, and drug treatments were added. Cell lysates was analyzed by Western blotting to confirm successful transfection.

2.4. Dosing

In cell experiments, Ari was dissolved in DMSO to prepare a 48 mmol/L stock solution. 5-HT was diluted with H2O to make a 40 mmol/L stock solution. The HTR2B inhibitor SB 204741 was dissolved in DMSO to prepare an 80 mmol/L stock solution. The concentration of cetuximab solution was 5 mg/mL, and the final concentration on CRC cells was 10 μL/mL. All drugs were diluted to the desired concentration with the medium. In the animal experiment, the animals were divided into solvent control, 10 mg/kg, and 30 mg/kg groups. Ari was ground into sub-divisions, then suspended in 0.5% CMC-Na, and administered by gavage twice a day for 14 days. The dose of cetuximab was 10 mg/kg intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection twice a week.

2.5. MTT, CCK8 assay, and colony formation assay

3000 cells in 100 μL medium were seeded into a 96-assay plate, incubated with drug for 24–72 h, and then incubated with MTT for 4 h. After that, the liquid in the plate was removed and 150 μL DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan. Absorbance was detected at a wavelength of 490 nm on 680 Microplate Reader (BIO-RAD, CA, USA). The viability of transfected cells was detected by CCK8 assay. Colony formation assays were performed as follows: Cells were seeded at 200 cells per well in 6-well plate and cultured in a medium containing the control DMSO and various concentrations of Ari. After 14 days, cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and photographed after staining with crystal violet.

2.6. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated from cells using TRIzol reagent (Accurate Biology, China), and the cDNA was synthesized using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (ThermoFisher, Waltham, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed in BIO-RAD CFX Connect real-time PCR detection system (BIO-RAD, CA, USA). Actin was used as a housekeeping reference gene, and the relative quantities of mRNAs were calculated based on their 2–ΔΔCt values. The primer sequences were listed in Supporting Information Table S2.

2.7. Animal experiments

All experimental animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of southwest university, IACUC approval No.: IACUC-20210930-01. Four-week-old female BALB/c nude mice were acclimated to the environment for about a week before in vivo experiments. 2 × 106 HT29 cells were injected subcutaneously into the right limb of BALB/c nude mice. After 2 weeks of administration, the mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and the specimens were collected.

2.8. Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) staining

Formalin-fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin blocks and tissue sections were cut to 3 μm. The samples were dewaxed and rehydrated in a xylene ethanol–water gradient system, and experiments were carried out with Hematoxylin–Eosin Staining Kit (Solarbio) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Histopathological examination was performed under an Olympus light microscope (Waltham, MA, USA).

2.9. Immunochemistry (IHC)

Formalin-fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin blocks and tissue sections were cut to 3 μm. The samples were dewaxed and rehydrated in a xylene ethanol–water gradient system, and experiments were carried out with SP Kit (Broad Spectrum, Solarbio) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Histopathological examination was performed under an Olympus light microscope (Waltham, MA, USA).

2.10. Protein extraction and Western blot

Cell and tissue proteins were extracted with a suspension of RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime) and 1% protein phosphatase inhibitor (Servicebio). Cells were lysed on ice for 10 min, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm (Sorvall legend micro 17R, ThermoFisher, Waltham, USA) under 4 °C for 20 min. The proteins were fractionated on SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to the PVDF membrane (Merck, Germany). After blocking with 5% skim milk-PBST for 1.5 h at room temperature, the PVDF membrane was washed three times with PBST and incubated overnight at 4 °C with the corresponding antibodies. The membranes were washed with PBST and incubation with secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Enhanced chemiluminescence reagents were employed to visualize the protein bands on the membranes. The densities of specific bands were performed by using ImageJ software.

2.11. Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay

The cells were treated with Ari for 30 min, and collected after gentle lysing, after which centrifuged at 12,000 rpm (Sorvall legend micro 17R, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA) under 4 °C for 10 min. Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) was performed with the SureBeads Protein G Magnetic Beads (BIO-RAD, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The enriched proteins on magnetic strains were collected, and analyzed by Western blot experiments.

2.12. Cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA)

Two equal volumes of Ari treated and untreated cell suspensions were obtained after counting with a hemocytometer. Then, the cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in 550 μL PBS with phosphatase inhibitor, and mixed evenly. Each group was divided into 5 equal tubes and heated together at 42, 45, 48, 51, and 54 °C for 3 min. After that, the samples were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then rewarmed at 25 °C, repeated twice. Later, the samples were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm (Sorvall legend micro 17R, ThermoFisher, Waltham, USA) under 4 °C for 10 min, the supernatant was collected to prepare protein loading buffer for Western blotting.

2.13. Molecular docking

The crystal structures of Gαq were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database (PDB ID: 3AH8). Water molecules and ligand YM were removed from crystal structures, followed by the addition of only polar hydrogen. The crystal structures of the proteins were saved in. pdbqt format prior to conducting the docking experiment. The structure of Ari was obtained from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) in. sdf format. The molecular docking among ligands and proteins was carried out using Discovery studio; the LibDock score of the docking was 145.6. Finally, the docking results were visualized using PyMOL viewer.

2.14. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 19.0 software and GraphPad Prism 8. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) from three repeated experiments. For multiple groups comparison, Statistical analysis of differences between group mean was calculated by one-way ANOVA with LSD multiple comparison test, and the differences were considered significant when P < 0.05. Comparisons between the two groups were performed using a two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test, and differences between groups were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Ari inhibited the proliferation of CRC cells in vitro

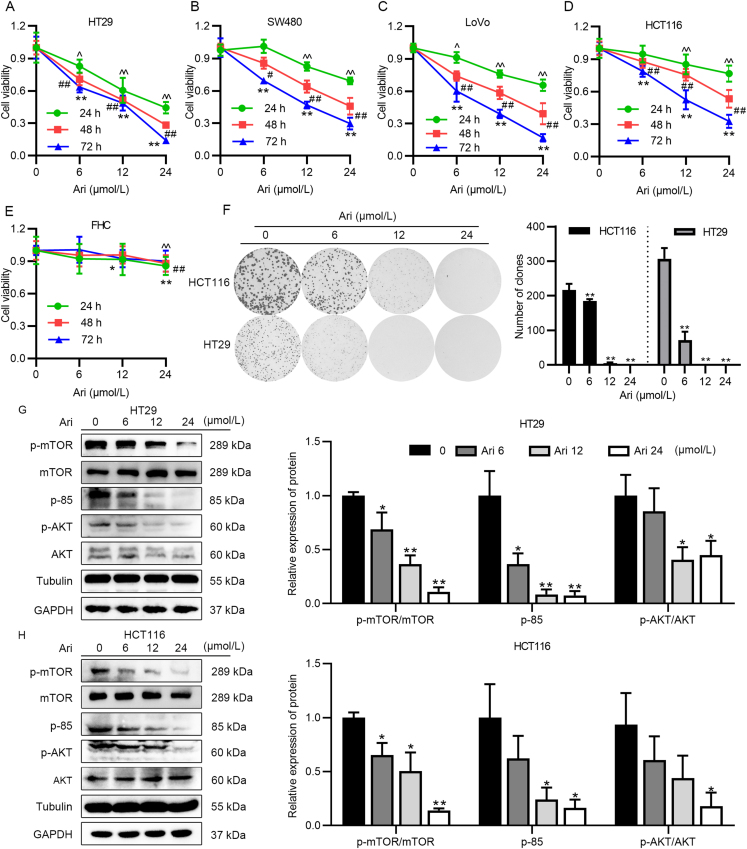

We screened several cell lines to examine the anticancer activity of Ari, including lung cancer, cervical cancer, neuroblastoma, breast cancer (Supporting Information Fig. S1A–S1D), and CRC cells. Among them, Ari exhibited a superior inhibitory effect on different types of CRC cells, and the proliferation of all CRC cell lines were inhibited by Ari in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A–D). Then we detected the lethality of Ari on normal colonic cells FHC and found that the inhibitory effect of Ari on FHC was lower than that on CRC cells (Fig. 1E), indicating an acceptable safety profile of Ari. Interestingly, two other third-generation antipsychotics, brexpiprazole (Bre) and cariprazine (Car) also inhibited HT29 cell proliferation, but had different effects on FHC cells (Fig. S1E–S1H). The IC50 value of Ari, Bre and Car on HT29 cell were about 12.77, 20.82, and 14.59 μmol/L, the IC50 value of Ari and Bre on FHC cell were higher than 100 μmol/L, but the IC50 value of Car on FHC cell was about 34.94 μmol/L, the IC50 value of olanzapine (Ola) on HT29 cell was about 132.95 μmol/L (Fig. S1I and S1J). These results suggest that the anti-CRC effects of second-generation antipsychotics were weaker than those of third-generation antipsychotics. But Car had a poor safety profile, Bre have not been approved for marketing in China yet, and as a marketed drug, Ari is of great significance if its anticancer effect is expanded.

Figure 1.

Ari inhibited CRC cell proliferation in vitro. (A)–(E) Inhibitory ability of Ari on HT29, LoVo, SW480, HCT116 FHC cells. These results are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 6; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 (^ for 24 h, # for 48 h, ∗ for 72 h) vs. control group. (F) Ari reduced the number of HT29 and HCT116 cells' monoclonal formation at a concentration of 12 μmol/L for 14 days. (G, H) The protein expression of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway after Ari treatment in HT29 and HCT116 cells. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. control group.

Next, HT29 and HCT116 were appointed as cell models for subsequent experiments. The monoclonal formation experiment showed that the formation of HT29 and HCT116 cell colonies was decreased with increasing concentration of Ari (Fig. 1F). We examined some proliferation-related pathway signaling and found that Ari inhibited PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling. It can be seen from the Western blot results that Ari significantly reduced the relative protein expression of p-mTOR, p-85, and p-AKT in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1G). The same results also appeared in HCT116 cells; the relative expression levels of p-mTOR, p-85, and p-AKT markedly decreased by Ari treatment (Fig. 1H). Since the two housekeeping genes, GAPDH and Tubulin, were unaffected by Ari, either of them were used as a reference protein. These results suggest that Ari exerted anti-proliferation effects on CRC cells and altered the proliferation-related signaling pathways in vitro.

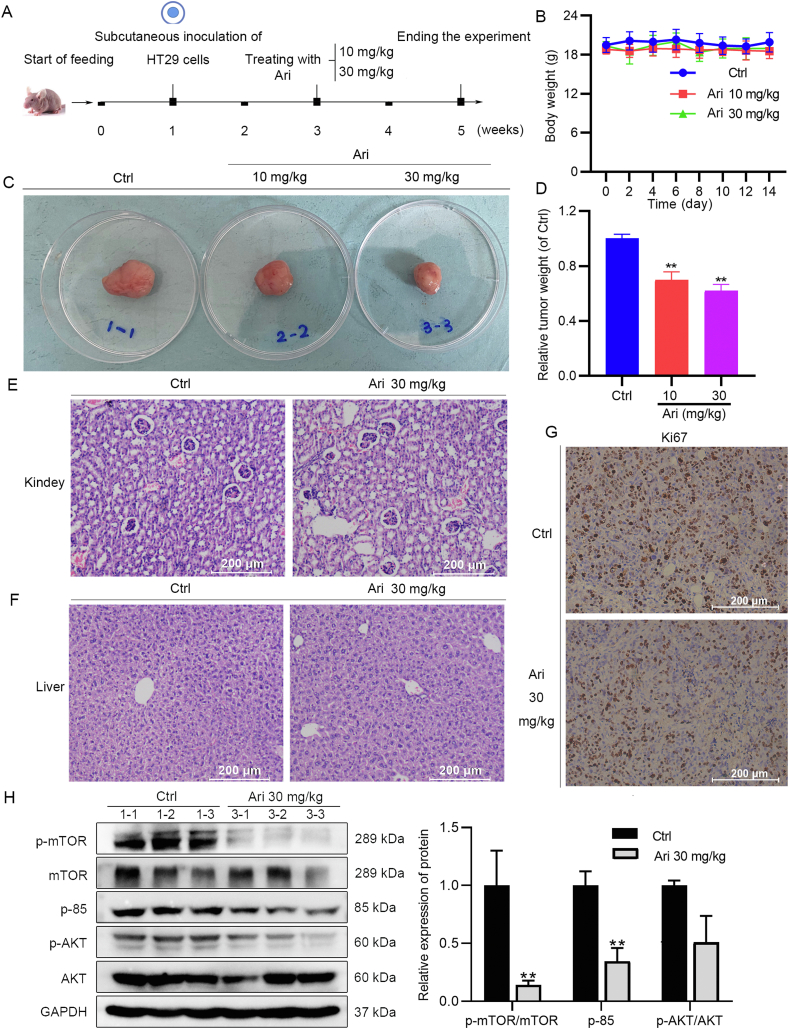

3.2. Anti-CRC activity of Ari was confirmed in nude mice

Due to the complex absorption and distribution of drugs in the body, it is necessary to move forward with animal experiments immediately after determining the in vitro activity of Ari. Animal experiments were carried out as shown in Fig. 2A. After the tumor-bearing mouse model was successfully established, the mice received either Ari or 0.5% CMC-Na by lavage twice a day. Animal experiments showed that 10 and 30 mg/kg Ari significantly slowed down the subcutaneous tumor growth compared to the control group (Fig. 2C and D). Ari did not affect the ordinary activity of the mice, and the body weight of the groups was stable throughout the experimental period (Fig. 2B). The results of H&E staining showed that the metabolism and excretion organs had no noticeable damage under the high concentration of Ari treatment. As shown in Fig. 2E and F, the morphology of hepatocytes was intact, and there was no inflammatory infiltration and morphological damage on the liver sections. Similarly, the glomerular structure in the kidney sections was clear and normal in shape without inflammatory infiltration and morphological damage. Moreover, the results of Ki67 IHC staining showed that 30 mg/kg Ari reduced Ki67 staining, indicating that Ari can inhibit the proliferation of xenograft tumors (Fig. 2G). Besides that, we also found the changes in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in the subcutaneous tumor tissue of nude mice, which is significantly decreased relative protein expression of p-mTOR and p-85 by Ari 30 mg/kg (Fig. 2H), confirming the ability of Ari against CRC.

Figure 2.

Ari inhibited subcutaneous xenograft tumor growth. (A) Animal experiment protocol. (B) The body weight of mice during Ari administration. (C, D) Tumor-bearing mass weight was significantly reduced by Ari. (E, F) H&E staining results of kidney and liver sections. (G) Ki67 was reduced in xenograft tumors. (H) The relative expression of p-mTOR and p-85 in xenograft tumors was changed after Ari treatment. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 3 for Western blot; n = 6 for animal experiment. ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. control group.

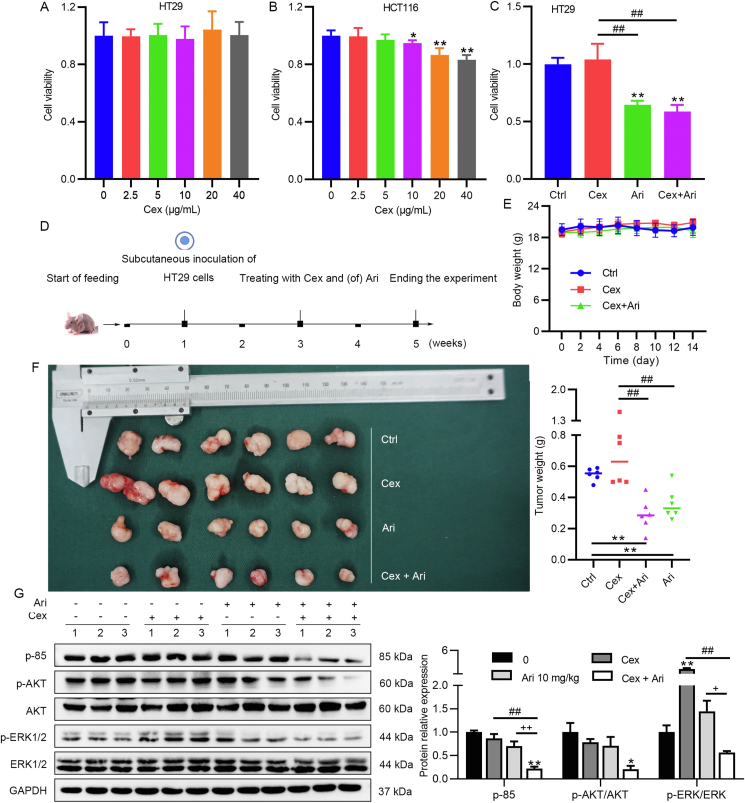

3.3. Ari is more potent than Cex against BRAF-mutated CRC

In this part of study, we aimed to elucidate whether the regulation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway by Ari is associated with EGFR signaling. EGFR inhibitors or targeted drugs were developed for anticancer therapy, such as cetuximab (Cex). When we treated CRC cells with Cex, the results showed that Cex had no effect on HT29 cells (BRAF-mutated cells) or slightly inhibited the activity of HCT116 cells (KRAS-mutated cells) at large doses (Fig. 3A and B). Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of Ari on HT29 cells was similar in the Ari + Cex group, but both were stronger than the Cex group (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that Ari might be more effective than Cex when BRAF mutations are present in CRC cells. Subsequently, we tested the effect of Ari and/or Cex in nude mice and obtained the same results as in vitro (Fig. 3D), with the body weight of mice in a stable state in the experimental group (Fig. 3E). As shown in Fig. 3F, Cex appeared to increase tumor size but without a statistical difference. The Ari + Cex group or the Ari group significantly suppressed tumor weight compared with the control group or the Cex group (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3.

Ari inhibited CRC cell growth not perturbed by BRAF mutation. (A) Cex was ineffective on BRAF-mutated HT29 cells. (B) The effect of Cex on HCT116. (C) The effects of Cex and/or Ari on HT29 cells. (D) Animal experimental protocol. (E) The body weight of mice during Ari administration. (F) Cex was ineffective against xenograft tumors in vivo. (G) The changes of PI3K/AKT and ERK pathway-related factors after CEX and/or Ari treatment. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 3 for Western blot; n = 6 for animal experiment. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. control group; ##P < 0.01 vs. the Cex group; +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01 vs. the Ari group.

Theoretically, a retaliatory activation of ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT signaling by EGFR inhibitors is responsible for drug resistance in BRAF-mutated CRC and, in more severe cases, may aggravate cancer progression. Western blot results showed that Cex significantly increased the expression of p-ERK1/2, and the relative expression of p-85 and p-AKT was similar to that of the control group. Ari at 10 mg/kg had no significant effect on these factors, but Ari combined with Cex significantly reduced the expression of p-ERK1/2 and p-85 compared with the single treatment group (Fig. 3G). These results suggest that EGFR inhibitor had no effect in BRAF-mutated HT29 cells, whereas Ari was significantly effective. Cex caused ERK signaling pathway activation, which should be the reason for Cex resistance. Cex combined with Ari enhanced the inhibition of ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. Therefore, we hypothesized that Ari might modulate ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT signaling in a different way from EGFR signaling inhibition.

3.4. The inhibitory effect of Ari on CRC cells is bound up with HTR2B signaling

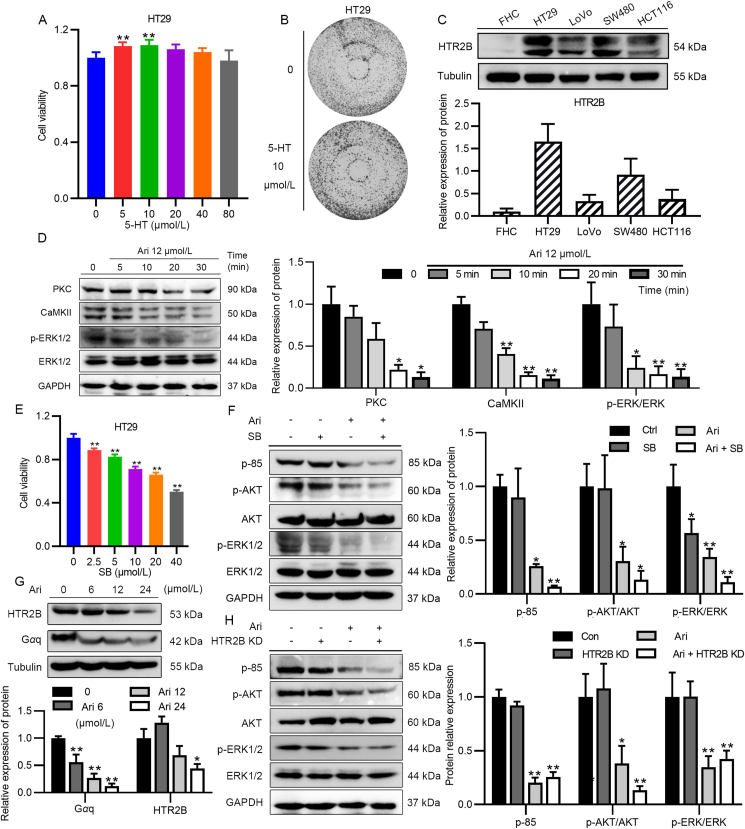

Considering the regulation of 5-HTRs is one of the most significant characteristics of the third-generation antipsychotics, the aforementioned Bre and Car, which have strong regulation of 5-HTR especially their strong affinity and inverse agonist effect on HTR2B, has attracted our attention. To confirm that 5-HT is associated with cell growth, we incubated HT29 in a medium containing increasing doses of 5-HT to examine whether 5-HT receptors were involved in CRC cell proliferation. After 48 h incubation, MTT assay showed that 10 μmol/L 5-HT slightly stimulated the proliferation of HT29 (Fig. 4A), and the results of colony formation assay also showed that after 7 days of incubation with 5-HT, the number of cells in the plate was more than that in the untreated group (Fig. 4B). The growth of CRC cells was stimulated by 5-HT, indicating that 5-HTRs signaling participates in cell proliferation. Drug efficacy is closely related to the abundance of target receptors and the affinity of drugs to receptors. Following that Ari had the strongest inhibitory effect on HT29 cells, we performed qPCR experiments to examine the distribution of HTR2B and other 5-HTRs in CRC cells (Supporting Information Fig. S2A–S2G). The results show a high level of HTR2B and HTR1D mRNA in HT29 (Fig. S2C and S2E). However, Ari has a low affinity for HTR1D, and we finally identified HTR2B as the research target. The Western blot results show that HTR2B protein was abundantly expressed in HT29 cells, but rarely in FHC (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Ari inhibited CRC cell proliferation through HTR2B signaling. (A, B) 5-HT promoted HT29 growth. (C) The expression of HTR2B in FHC, HT29, LoVo, SW480, and HCT116. (D) The relative expression of PKC, CaMKII, and p-ERK1/2 after a brief Ari treatment. (E) SB 204741 inhibited HT29 cell activity in a dose-dependent manner. (F) SB decreased the relative expression of p-ERK1/2 in HT29 cells. (G) The relative expression of HTR2B and Gαq in HT29 cells after Ari treatment. (H) HTR2B KD did not arouse the signaling pathway changes. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 6 for MTT, n = 3 for Western blot; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. the control group.

At present, the role of Ari on HTR2B in CRC is unknown. By detecting the downstream factors of HTR2B in HT29 after Ari treatment, it was found that the expression of PKC and CaMKⅡ significantly decreased, and the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 also rapidly reduced (Fig. 4D), suggesting that Ari exerted a suppressive effect on HTR2B signaling in CRC cells. To investigate whether inhibition of HTR2B signaling causes anti-CRC effect, we used HTR2B-specific antagonist SB 204741 (SB) to treat HT29 cells and found that SB 204741 significantly reduced the growth rate of HT29 cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4E). We also examined the effect of SB 204741 on PI3K/AKT and ERK signaling pathways. As shown in Fig. 4F, ERK1/2 phosphorylation significantly reduced in HT29 cells after SB 204741 treatment, while the impact on p-85 and p-AKT was negligible, which was different from Ari alone (Fig. 4F).

Even though the inhibition of HTR2B signaling blocked ERK signaling, we still cannot explain the changes in PI3K/AKT signaling pathway caused by Ari. HTR2B is most distributed in HT29 with the highest Ari sensitivity, thus whether HTR2B itself has a biological effect is also worthy of investigation. The expression of HTR2B and its coupling protein Gαq were assayed after Ari administration, and the result shows that Ari reduced the relative expression of HTR2B and Gαq in HT29 cells (Fig. 4G). Additionally, we established HTR2B overexpressed (HTR2B) and HTR2B knockdown (HTR2B KD) cells (Fig. S2J). We found that endogenous alteration of HTR2B had no effect on cell growth, and the efficacy of Ari remained unchanged (Fig. S2H and S2I). HTR2B can be reduced by Ari, but knockdown of HTR2B did not affect the activity of PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Moreover, the relative expression levels of p-85, p-AKT and p-ERK1/2 were unchanged after HTR2B knockdown (Fig. 4H).

From the above results, we demonstrate that the HTR2B inverse agonist Ari efficiently inhibited HTR2B signaling in CRC cells. Inhibition of HTR2B signaling restricted CRC cell growth and resulted in the suppression of ERK signaling, suggesting that the anti-CRC effect of Ari came from its suppression of HTR2B signaling.

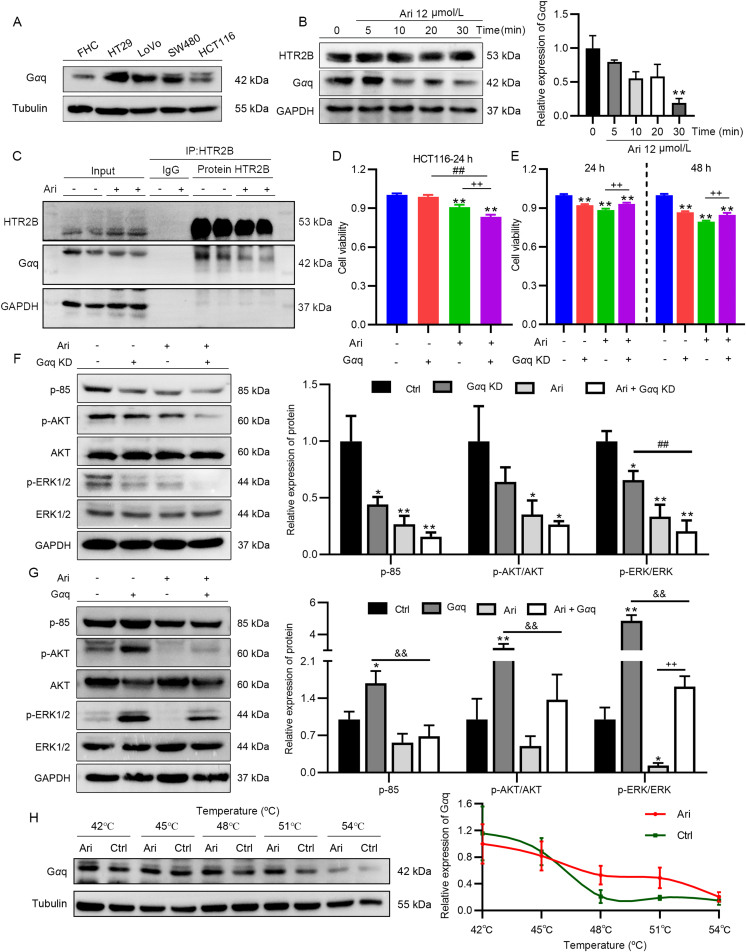

3.5. Ari targets Gαq coupled to HTR2B against CRC proliferation

In the following experiments, attention has been paid to the core molecule Gαq involved in the regulation of HTR2B signaling. Gαq is situated in cells and coupled to the GPCR. The expression of Gαq was examined in FHC, HT29, LoVo, SW480, and HCT116 cells. The results show that Gαq had the highest distribution in HT29 and the lowest distribution in normal colon cells (Fig. 5A). The results of the side-by-side comparison of HTR2B and Gαq are presented in Fig. S2L. Gαq was rapidly reduced after Ari treatment for 30 min, whereas HTR2B expression was unchanged under this condition (Fig. 5B). Not randomly varied, we enriched Gαq with an HTR2B antibody using a co-immunoprecipitation and found that Gαq co-precipitated with HTR2B was reduced after Ari treatment while HTR2B abundance was consistent (Fig. 5C), indicating that Ari rapidly reduced Gαq, which bound to HTR2B in CRC cells.

Figure 5.

Ari targeted Gαq to inhibit CRC cell proliferation. (A) Distribution of Gαq in CRC cells. (B) The relative expression of HTR2B and Gαq after Ari intervention for 30 min. (C) Gαq bound to HTR2B was decreased after Ari treatment. (D) The inhibitory effect of Ari on HCT116 was enhanced after Gαq overexpression. (E) Gαq KD inhibited HCT116 cell growth. (F, G) The relative expression of p-85, p-AKT, p-ERK1/2 in Gαq KD and Gαq overexpression cells. (H) CETSA experiment examined the thermal stability of Ari-treated Gαq. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. the control group; ##P < 0.01 vs. the Gαq group; ++P < 0.01 vs. the Ari group; &&P < 0.01 vs. the Gαq group.

However, the function of Gαq is unknown in CRC. To explore whether the inhibitory effect of Ari on CRC was associated with Gαq, we established CRC cells with endogenously overexpression or knockdown of Gαq. Among them, the Gαq-overexpressed cells showed good growth morphology and high fluorescence transfection rate (Fig. S2M). The morphology of Gαq knockout (Gαq KD) cells was altered but similar to the empty plasmid transfection group (Con) (Fig. S2N). The results of the relative expression of Gαq in the transfected cells showed that Gαq overexpression and knockdown cells were successfully constructed (Fig. S2K). Intriguingly, although overexpressing Gαq failed to promote HCT116 cell proliferation, it enhanced the inhibitory effect of Ari on HCT116. The CCK8 results show that, compared with the Ari group, the inhibition effect of Ari on HCT116 cells became stronger after Gαq overexpression (Fig. 5D). Knockdown of Gαq reduced the number of viable cells and also attenuated the anti-CRC effect of Ari (Fig. 5E). Then the mechanistic studies indicated that Gαq is functional. As shown in Fig. 5F, the relative expressions of p-85 and p-ERK1/2 decreased after Gαq knockdown, and because Ari can reduce Gαq content, Ari acts on Gαq KD cells with an additive effect on p-ERK1/2 inhibition (Fig. 5F). Conversely, overexpression of Gαq increased the relative expression of p-85, p-AKT, and p-ERK1/2 and significantly counteracted the inhibitory effect of Ari on p-ERK1/2 (Fig. 5G). Therefore, the inhibitory effect of Gαq on PI3K/AKT signaling might be the reason for its effect on the growth inhibition of CRC cells. However, the amount of Gαq in cells is also proportional to the efficacy of Ari, and the high affinity of Ari to Gαq-coupled receptor HTR2B and its inverse agonist effect suggest a special communication between Ari and HTR2B signaling molecule Gαq.

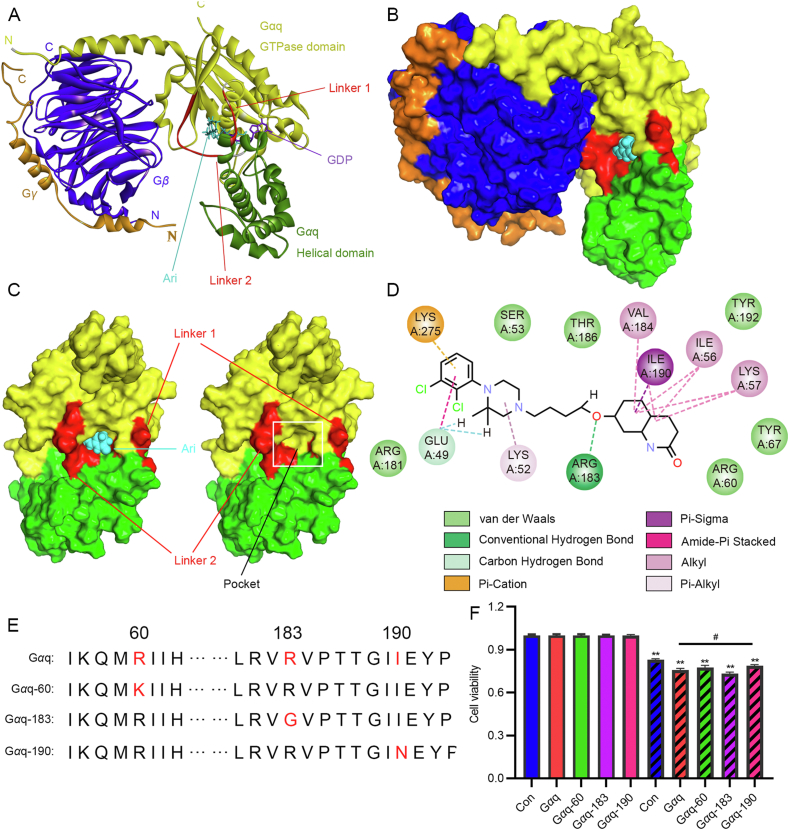

We first observed an interaction between Ari and Gαq. The CETSA results show that the thermal stability of Gαq in the Ari-treated group was higher than control with increasing temperature (Fig. 5H); Ari protected Gαq and slowed down its degradation during elevated temperature, suggesting that there was an interaction between Ari and Gαq. To further clarify the mechanism of Ari targeting Gαq, we established a molecular docking model between Ari and Gαq. We obtained the crystal structure of Gαq from PBD and conducted the molecular docking with Ari. The crystal structure of Gαqβγ shows the heterotrimer in which the binding of Gγ to Gβ forms extensive contacts with Gαq. Two interdomain linkers, Linker 1 and Linker 2, connect GTPase and helical domains, and GDP binds to a cleft between the GTPase and helical domains without contacting Gβγ. A docking-based model of the Gαq protein in the complex with Ari was based on the co-crystal structure of Gαqβγ bound with YM-254890 (PDB ID: 3AH8, resolution: 2.9 Å). The result shows that Ari docked into the cleft between Linker 1 and Linker 2 (Fig. 6A and B). The docking studies demonstrate that Ari anchored in the binding pocket and made intimate contacts with residues from Linker 2 (ARG183 and VAL184) and the GTPase domain (GLU49, LYS52, ILE56, LYS57, and ILE190), thereby repressing the release of GDP from Gαq (Fig. 6C and D). If GTP exchange is inhibited, and Gαq-mediated signaling will not exist. This provides a plausible explanation for the mechanism by which Ari inhibits Gαq-coupled HTR2B signaling. Based on the predicted results, ARG 60, ARG 183, and ILE 190 were selected to verify the regulation of Gαq by Ari. The wild-type plasmid and the mutant Gαq, Gαq-60, Gαq-183, Gαq-190 (Fig. 6E) were selected to be transfected into HCT116 cells, and the results show that the inhibitory effect of Ari on Gαq-190 was less strong than that of Gαq. Therefore, we considered that amino acid 190 might be the interaction site of Ari and Gαq, and Ari exerts anti-CRC activity by targeting Gαq via HTR2B.

Figure 6.

The structure of the Gαqβγ heterotrimer in complex with Ari. (A) Gαq consists of the GTPase (yellow) and the helical domains (green) connected by two linker regions, Linker 1 and Linker 2 (red), Gβ and Gγ are blue and orange, GDP (purple) and Ari (cyan) are shown as cartoon models. (B) Surface representation of the heterotrimer as shown in 6A. (C) On the left, it is a surface representation of the front view of Gαq, and on the right without Ari in the pocket. (D) The chemical bond formed by Ari with Gαq amino acid is shown. (E) Amino acid sequence of Gαq, Gαq-60, Gαq-183 and Gαq-190. (F) The effect of Ari on HCT116 cells transfected with Gαq, Gαq-60, Gαq-183 and Gαq-190. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3; ∗∗P < 0.01 vs. control group; #P < 0.05 vs. the Gαq group.

4. Discussion

Researchers have been trying to understand the pathogenesis of CRC and find new effective therapeutic drugs. In the field of view of drug development, looking for new indications of existing drugs is a low-cost and time-saving strategy. Previous epidemiological studies established that reductions in cancer mortality or prevalence were observed in people with a mental health condition, for which antipsychotics were used24,25, and fundamental research revealed that some antipsychotics have anticancer effects26. These findings imply that APDs have potential value in cancer treatment and deserve further investigation.

Ari is a third-generation atypical antipsychotic drug currently with a limited understanding of its anticancer effects and precise mechanisms. In this study, we found that Ari significantly inhibited CRC cell proliferation and colony formation in concentration-dependent manners in vitro and attenuated the growth of subcutaneous xenograft tumors. Mechanistically, we observed the effect of Ari on the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis. The literature reported that the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling triggered by EGFR activation promotes tumor proliferation and progression, and compared with normal tissues, EGFR is frequently overexpressed and activated in CRC27. These characteristics bring EGFR into consideration as an effective target against CRC. However, it should be noted that inhibition of EGFR is not always effective in BRAF-mutated cells. Although the effect of EGFR antagonists is feasible in some BRAF-mutated melanoma28, they are less effective in BRAF-mutated CRC5. Our study shows that Cex was ineffective in HT29 cells with BRAF mutation29, and that there were no changes in PI3K/AKT and p-ERK signaling after Cex treatment. However, low-dose (10 mg/kg) of Ari inhibited the proliferation of xenograft tumors and greatly reduced the p-ERK1/2 surge caused by Cex. It is possible that Ari possesses different mechanisms at low and high doses, which is worthy of a follow-up study. Nevertheless, the remarkable anti-growth effect of Ari on HT29 cells suggests that Ari may be a promising repurposed drug for common CRC and those refractory to EGFR inhibitors.

Some researchers attribute the anticancer activity of antipsychotics to D2R antagonism13. But the results of our study show that the inhibitory effect of Ola on HT29 was not as significant as that of Ari, and that Bre and Car, two other third-generation antipsychotics, also possessed potent inhibitory effects on HT29 cells. The targets of the third-generation antipsychotics have been adjusted to partial D2R and HTR1 agonist and antagonism of HTR230 in order to reduce adverse reactions with improved efficacy. Therefore, we propose that targeting 5-HTR is an important condition for Ari to exhibit anticancer effects. We examined the distribution of 5-HT receptors in different CRC cell lines in this study, and our attention was drawn to the high sensitivity of HT29 to Ari, HTR1D and HTR2B, which have the highest distribution in HT29. And because 5-HT1 receptor antagonism is known to inhibit CRC cell proliferation31, HTR1D may not be an actual target of Ari for anticancer effect, either. Ari has an extremely strong affinity for HTR2B and is known to act as an inverse agonist of it, but HTR2B's role in CRC was rarely reported. Our experiments confirmed that Ari inhibited HTR2B signaling, just as HTR2B-specific inhibitors did, and they both inhibited CRC cell proliferation. Considering that some 5-HTRs are involved in the regulation of cancer progression independent of signaling, such as knockdown of HTR1D, HTR3A, and HTR7 inhibited cancer cell growth32, 33, 34, we also established HTR2B overexpression and knockdown models. Based on our established models, we found that CRC cell growth was not inhibited, while Gαq, a coupling protein involved in HTR2B signaling, played an important role in the inhibitory effect of Ari on CRC cell proliferation.

Gαq is a structural component of some GPCRs located within the cell membrane35 and participates in HTR2B signaling regulation. In theory, there are two main ways to regulate Gαq-related signaling: mutated self-activation and ligand-dependent Gαq-coupled GPCR activation36,37. Mutated self-activation is caused by GNAQ gene mutations and occurs more frequently in uveal melanoma38 than in CRC. There were no Gαq mutations in CRC cells in our study, but we observed a decrease in Gαq expression after Ari intervention, and a decrease in cell growth rate, and the relative expression of p-85 and p-ERK1/2 after Gαq knockdown. Those suggest that wild Gαq may be associated with the maintenance of CRC growth. Another type of Gαq signaling is associated with GPCR. HTR2B has been classified as a Gαq-coupled GPCR, and its signaling depends on the Gαq state. Once the Gαq conformation cannot change, it leads to inhibition of GPCR signaling39,40; in short, having the property to target Gαq is the key to limiting HTR2B signaling. Our study shows that Ari significantly inhibited Gαq-rich HT29 cells, but had little effect on Gαq-low FHC cells, and overexpression of Gαq in HCT116 cells enhanced the efficacy of Ari, all of which suggest that Gαq might be a potential target of Ari. Since the enhanced thermal stability of Gαq in CETSA suggested an interaction between Ari and Gαq, we further simulated the binding between Ari and Gαq based on the crystal model41, and found that the chemical bound interaction between Ari and Gαq was similar to YM-25489042, limiting the conversion between GDP and GTP. Ultimately, amino acid 190 of Gαq was found to carry the therapeutic effect of Ari, suggesting that Ari inhibited CRC cell proliferation by targeting Gαq.

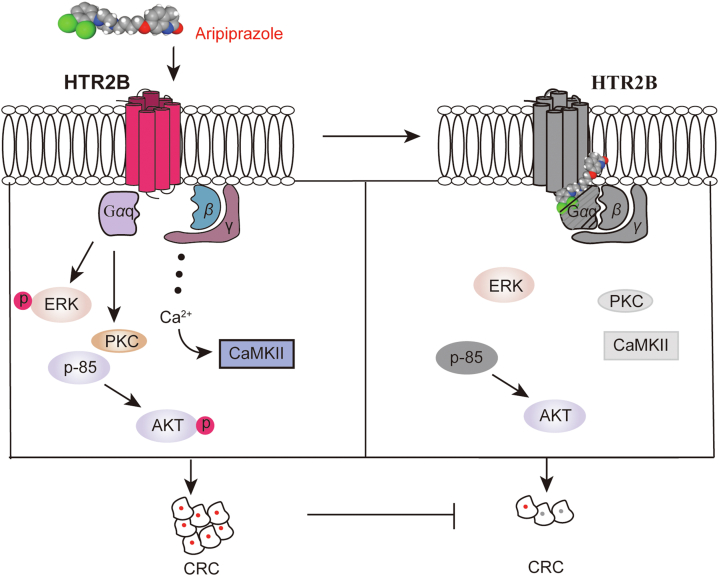

5. Conclusions

We revealed that Ari, a drug to treat schizophrenia in clinic, suppressed BRAF-mutated CRC cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo. By analyzing the distribution of the 5-HT receptor and Gαq, the physiological of HTR2B signaling, and the relationship between Ari and Gαq, we conclude that Gαq coupled to HTR2B is the target of Ari and is required for the anti-CRC bioactivity of Ari. Collectively, Gαq-coupled HTR2B may be a therapeutic target in CRC (Fig. 7). Our study supports the development of Ari as a potential drug for treating CRC and provides new evidence for the reuse of antipsychotics in cancer treatment.

Figure 7.

A working model summarizes how Ari suppresses CRC cell proliferation.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by Chongqing basic research and frontier exploration project (cstc2022ycjh-bgzxm0119, China).

Author contributions

Changhua Hu, Xuemei Liu and Haowei Liu designed the research. Haowei Liu and Qiuming Huang conducted research. Bo Li, Yunqi Fan and Haowei Liu analyzed the data. Changhua Hu, Haowei Liu drafted the manuscript. Changhua Hu, Xuemei Liu and Haowei Liu revised the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2023.05.015.

Contributor Information

Xuemei Liu, Email: liuxm@swu.edu.cn.

Changhua Hu, Email: chhhu@swu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Fuchs H.E., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grothey A., Fakih M., Tabernero J. Management of BRAF-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer: a review of treatment options and evidence-based guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:959–967. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.03.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Z.N., Zhao L., Yu L.F., Wei M.J. BRAF and KRAS mutations in metastatic colorectal cancer: future perspectives for personalized therapy. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2020;8:192–205. doi: 10.1093/gastro/goaa022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopetz S., Guthrie K.A., Morris V.K., Lenz H.J., Magliocco A.M., Maru D., et al. Randomized trial of irinotecan and cetuximab with or without vemurafenib in BRAF-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer (SWOG S1406) J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:285–294. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keum N., Giovannucci E. Global burden of colorectal cancer: emerging trends, risk factors and prevention strategies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:713–732. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kannen V., Bader M., Sakita J.Y., Uyemura S.A., Squire J.A. The dual role of serotonin in colorectal cancer. Trends Endocrinol Metabol. 2020;31:611–625. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu P., Lu T., Chen Z., Liu B., Fan D., Li C., et al. 5-Hydroxytryptamine produced by enteric serotonergic neurons initiates colorectal cancer stem cell self-renewal and tumorigenesis. Neuron. 2022;110:2268–2282. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2022.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balakrishna P., George S., Hatoum H., Mukherjee S. Serotonin pathway in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:1268. doi: 10.3390/ijms22031268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maroteaux L., Ayme-Dietrich E., Aubertin-Kirch G., Banas S., Quentin E., Lawson R., et al. New therapeutic opportunities for 5-HT2 receptor ligands. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;170:14–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnes N.M., Ahern G.P., Becamel C., Bockaert J., Camilleri M., Chaumont-Dubel S., et al. International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. CX. Classification of receptors for 5-hydroxytryptamine; pharmacology and function. Pharm Rev. 2021;73:310–520. doi: 10.1124/pr.118.015552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang S.H., Li J., Dong F.Y., Yang J.Y., Liu D.J., Yang X.M., et al. Increased serotonin signaling contributes to the warburg effect in pancreatic tumor cells under metabolic stress and promotes growth of pancreatic tumors in mice. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:277–291. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mao L., Xin F., Ren J., Xu S., Huang H., Zha X., et al. 5-HT2B-mediated serotonin activation in enterocytes suppresses colitis-associated cancer initiation and promotes cancer progression. Theranostics. 2022;12:3928–3945. doi: 10.7150/thno.70762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roney M.S.I., Park S.K. Antipsychotic dopamine receptor antagonists, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Arch Pharm Res (Seoul) 2018;41:384–408. doi: 10.1007/s12272-018-1017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.You F., Zhang C., Liu X., Ji D., Zhang T., Yu R., et al. Drug repositioning: using psychotropic drugs for the treatment of glioma. Cancer Lett. 2022;527:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu L., Jin W., Zhang J., Zhu L., Lu J., Zhen Y., et al. Repurposing non-oncology small-molecule drugs to improve cancer therapy: current situation and future directions. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:532–557. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang J., Zhao D., Liu Z., Liu F. Repurposing psychiatric drugs as anti-cancer agents. Cancer Lett. 2018;419:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chou F.H.C., Tsai K.Y., Wu H.C., Shen S.P. Cancer in patients with schizophrenia: what is the next step?. Psychiatr Clin Neurosci. 2016;70:473–488. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tung M.C., Lin Y.W., Lee W.J., Wen Y.C., Liu Y.C., Chen J.Q., et al. Targeting DRD2 by the antipsychotic drug, penfluridol, retards growth of renal cell carcinoma via inducing stemness inhibition and autophagy-mediated apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13:400. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-04828-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng C., Yu X., Liang Y., Zhu Y., He Y., Liao L., et al. Targeting PFKL with penfluridol inhibits glycolysis and suppresses esophageal cancer tumorigenesis in an AMPK/FOXO3a/BIM-dependent manner. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:1271–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tegowski M., Fan C., Baldwin A.S. Thioridazine inhibits self-renewal in breast cancer cells via DRD2-dependent STAT3 inhibition, but induces a G1 arrest independent of DRD2. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:15977–15990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.003719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lally J., MacCabe J.H. Antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: a review. Br Med Bull. 2015;114:169–179. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldv017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shirley M., Perry C.M. Aripiprazole (ABILIFY MAINTENA®): a review of its use as maintenance treatment for adult patients with schizophrenia. Drugs. 2014;74:1097–1110. doi: 10.1007/s40265-014-0231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki S., Okada M., Kuramoto K., Takeda H., Sakaki H., Watarai H., et al. Aripiprazole, an antipsychotic and partial dopamine agonist, inhibits cancer stem cells and reverses chemoresistance. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:5153–5161. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahar A.L., Kurdyak P., Hanna T.P., Coburn N.G., Groome P.A. The effect of a severe psychiatric illness on colorectal cancer treatment and survival: a population-based retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown J.S. Treatment of cancer with antipsychotic medications: pushing the boundaries of schizophrenia and cancer. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;141 doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nordentoft M., Plana-Ripoll O., Laursen T.M. Cancer and schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatr. 2021;34:260–265. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan K., Valeri N., Dearman C., Rao S., Watkins D., Starling N., et al. Targeting EGFR pathway in metastatic colorectal cancer—tumour heterogeniety and convergent evolution. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;143:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pastwinska J., Karas K., Karwaciak I., Ratajewski M. Targeting EGFR in melanoma—the sea of possibilities to overcome drug resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2022;1877 doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2022.188754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berg K.C., Eide P.W., Eilertsen I.A., Johannessen B., Bruun J., Danielsen S.A., et al. Multi-omics of 34 colorectal cancer cell lines — a resource for biomedical studies. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:116. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0691-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Preda A., Shapiro B.B. A safety evaluation of aripiprazole in the treatment of schizophrenia. Expet Opin Drug Saf. 2020;19:1529–1538. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2020.1832990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corvino A., Fiorino F., Severino B., Saccone I., Frecentese F., Perissutti E., et al. The role of 5-HT1A receptor in cancer as a new opportunity in medicinal chemistry. Curr Med Chem. 2018;25:3214–3227. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666180209141650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gautam J., Bae Y.K., Kim J.A. Up-regulation of cathepsin S expression by HSP90 and 5-HT7 receptor-dependent serotonin signaling correlates with triple negativity of human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;161:29–40. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-4027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang J., Wang Z., Liu J., Zhou C., Chen J. Downregulation of 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 3A expression exerts an anticancer activity against cell growth in colorectal carcinoma cells in vitro. Oncol Lett. 2018;16:6100–6108. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin X., Li H., Li B., Zhang C., He Y. Knockdown and inhibition of hydroxytryptamine receptor 1D suppress proliferation and migration of gastric cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022;620:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.06.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inoue A., Raimondi F., Kadji F.M., Singh G., Kishi T., Uwamizu A., et al. Illuminating G-protein-coupling selectivity of GPCRs. Cell. 2019;177:1933–1947. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mafi A., Kim S.K., Goddard W.A. The mechanism for ligand activation of the GPCR-G protein complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2110085119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kostenis E., Pfeil E.M., Annala S. Heterotrimeric Gq proteins as therapeutic targets?. J Biol Chem. 2020;295:5206–5215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV119.007061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jager M.J., Shields C.L., Cebulla C.M., Abdel-Rahman M.H., Grossniklaus H.E., Stern M.H., et al. Uveal melanoma. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2020;6:24. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang J., Hua T., Liu Z.J. Structural features of activated GPCR signaling complexes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2020;63:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hilger D., Masureel M., Kobilka B.K. Structure and dynamics of GPCR signaling complexes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018;25:4–12. doi: 10.1038/s41594-017-0011-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishimura A., Kitano K., Takasaki J., Taniguchi M., Mizuno N., Tago K., et al. Structural basis for the specific inhibition of heterotrimeric Gq protein by a small molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13666–13671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003553107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang H., Nielsen A.L., Stromgaard K. Recent achievements in developing selective Gq inhibitors. Med Res Rev. 2020;40:135–157. doi: 10.1002/med.21598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.