Abstract

The H4 subtype of avian influenza viruses has been widely distributed among wild birds. During the surveillance of the avian influenza virus in Shanghai from 2019 to 2021, a total of 4,451 samples were collected from wild birds, among which 46 H4 subtypes of avian influenza viruses were identified, accounting for 7.40% of the total positive samples. The H4 subtype viruses have a wide range of hosts, including the spot-billed duck, common teal, and other wild birds in Anseriformes. Among all H4 subtypes, the most abundant are the H4N2 viruses. To clarify the genetic characteristics of H4N2 viruses, the whole genome sequences of 20 H4N2 viruses were analyzed. Phylogenetical analysis showed that all 8 genes of these viruses belonged to the Eurasian lineage and closely clustered with low pathogenic avian influenza viruses from countries along the East Asia-Australia migratory route. However, the PB1 gene of 1 H4N2 virus (NH21920) might provide its internal gene for highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N8 viruses in Korea and Japan. At least 10 genotypes were identified in these viruses, indicating that they underwent multiple complex recombination events. Our study has provided a better epidemiological understanding of the H4N2 viruses in wild birds. Considering the mutational potential, comprehensive surveillance of the H4N2 virus in both poultry and wild birds is imperative.

Key words: H4N2 avian influenza virus, epidemiology, phylogenetic analysis, recombination, Shanghai

INTRODUCTION

Avian influenza (AI) is a contagious disease caused by the avian influenza virus (AIV) in domestic poultry and wild birds. AIVs occasionally spill over to humans and other mammals through cross-host transmission, causing a high mortality rate and posing a major threat to public health concerns as well as serious economic consequences in the fowl industry. According to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) classification, AIVs belong to the genus Influenza A virus of the family Orthomyxoviridae. Based on the antigenic properties of 2 surface glycoproteins, AIVs are classified into 16 hemagglutinin (HA) subtypes (H1–H16) and 9 neuraminidase (NA) subtypes (N1–N9). Wild birds are the natural reservoir of AIVs and harbor all known recognized HA (H1–H16) and NA (N1–N9) subtypes (Fouchier et al., 2005).

H4 subtype AIVs were prevalent in wild birds (Olsen et al., 2006; Diskin et al., 2020) and had a wide host range, including chickens (Liu et al., 2003; Liang et al., 2016), turkeys (Donis et al., 1989), waterfowls (Wille et al., 2022a), seals (Hinshaw et al., 1984), and pigs (Karasin et al., 2000; Abente et al., 2017), etc. H4 subtype AIVs have been distributed worldwide (Song et al., 2017). In Korea, the isolation rate of H4 subtype AIVs accounted for 17.4% of the total number of positive samples (n = 54) (Kang et al., 2013). In northeastern Spain, the positive proportion of H4 subtype viruses accounted for 21.4% of wild birds (Busquets et al., 2010), and was the most frequent HA subtype. H4 subtype AIVs were also one of the most common viruses isolated from wild birds in Australia during 2006 to 2020 (n = 24/313) (Wille et al., 2022a) as well as which in Arctic ducks (Gass et al., 2022).

H4 AIVs are classified as low pathogenic avian influenza viruses (LPAIVs), but they have the potential to contribute their internal gene segments to highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses (HPAIVs) (Cui et al., 2022). Similarly, H9N2 AIVs could be gene donors to facilitate the generation of novel highly pathogenic reassortants such as H5N6, H7N9, and H5N1 AIVs (Guan et al., 2000; Bi et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2017). Besides wild birds, H4 subtype AIVs have been found to be transmissible to poultry, which might result in a higher mutation rate of AIVs (Kim et al., 2022). Moreover, the H4 subtype AIVs have been detected in pigs and can replicate in the respiratory tracts of mice without prior adaptation, and transmit between guinea pigs by direct contact (Liang et al., 2016). Although the human infection reports with H4 subtype AIVs are not yet available worldwide, previous studies have shown that antibody titers against avian H4 were slightly elevated in turkey workers (Kayali et al., 2010, 2011). Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that H4 subtypes may possess higher pathogenicity and transmissibility through cross-species transmission in the future.

The East Asia-Australia migratory route is one of the most important routes for migration in China (Yong et al., 2015). As an important city on the eastern coast of China, Shanghai serves as a key breeding and stopover site along this migratory route (He et al., 2017). Wild birds, primarily waterfowls of the Anseriformes and Charadriiformes species, can serve as vectors for the intercontinental transmission of AIVs and result in genetic recombination (Venkatesh et al., 2018). During our routine surveillance from 2016 to 2018, we found that the H4 subtype was one of the most common subtypes, and H4N2 viruses could be detected throughout the entire study period (Tang et al., 2020). However, the epidemiology and genetic characteristics of the H4 subtype AIVs are still relatively poorly understood.

In this study, swab and fecal samples from wild birds were collected at several major migratory bird habitats in Shanghai between 2019 and 2021. All the samples were tested for AIVs and subjected to molecular and phylogenetic analysis to better understand the epidemiologic and evolutionary patterns of H4 AIVs in wild birds. In summary, our study emphasizes the importance of ongoing surveillance of H4 subtype AIVs in different species of wild birds worldwide.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample Collection

During the autumn migration season of wild birds from 2019 to 2021, healthy wild birds were captured in Chongming Dongtan (31°25′ to 31°38′ N, 121°53′ to 122°0′ E), Jiuduansha (31°06′ to 31°14′ N, 121°46′ to 122°15′ E), and Nanhui Dongtan (30°51′ to 31°06′ N, 121°50′ to 121°51′ E) wetlands in Shanghai, with permission and supervision of the Shanghai Wild Life Conservation and Management Office (2019–2021 [64], [32]). Oropharyngeal and cloacal swabs as well as feces samples were collected from the birds before they were released. The collected samples were individually placed in 2 mL of virus transport media (VTM), transported to the laboratory within 24 h in a refrigerated environment, and stored frozen at −80°C for further molecular analysis. All the experiments with H4N2 viruses were conducted with the biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) facility at East China Normal University.

Virus Detection and Sequencing

Viral RNAs were extracted directly from samples using the MagMAX Pathogen RNA/DNA Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on a MagMAX Express-96 Deep Well Magnetic Particle Processor (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Real-time reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) using matrix gene primers and probe was used to detect influenza A viruses, and then positive samples were transcribed into cDNA using the Unit12 primer and PrimScript TMII 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). Hemagglutinin and neuraminidase were determined using universal primers (Huang et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2019). The full-length 8 segments of H4N2 were amplified using the universal primers (Hoffmann et al., 2001). All sequences were confirmed with the BigDye termination kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on an ABI 3730 sequence analyzer.

Sequence Analysis

DNAMAN program (version 6.0) was used for sequence data analysis and alignment, while other sequences used for phylogenetic analysis were obtained from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and the Global Initiative on Sharing Avian Influenza Data (GISAID) EpiFlu database (http://platform.gisaid.org/epi3/frontend#43209d). Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the maximum-likelihood (ML) trees in MEGA version 6 (http://www.megasoftware.net/) with 1,000 bootstraps.

RESULTS

Prevalence of H4 Subtype Viruses in Wild Birds Globally

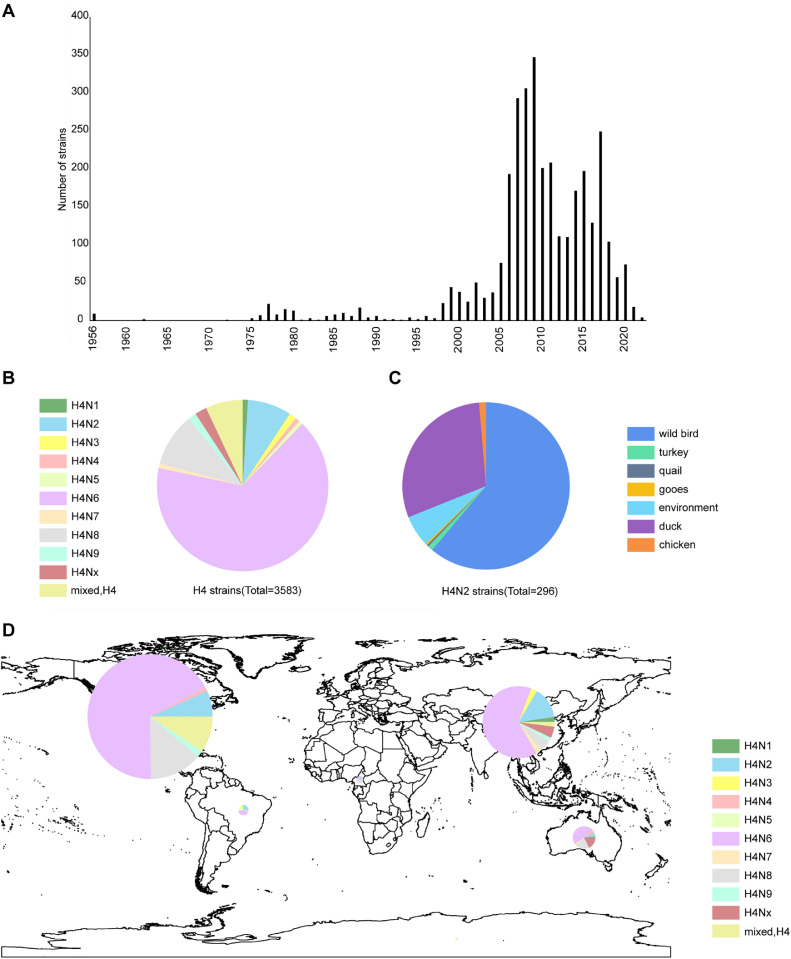

To better summarize the epidemiological characteristics of H4 subtype viruses, we downloaded data for all H4 subtype viruses (up to April 10, 2023) from the GISAID EpiFlu database (https://platform.epicov.org/epi3/cfrontend#3f1f) and GenBank databases (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). After removing duplicate data, a total of 3,584 H4 subtype viruses were obtained. The number of H4 isolates has shown an increasing annual trend since 2005 (Figure 1A), which was attributed to the global extensive surveillance of avian influenza in wild birds from that time. The results indicated that H4 subtypes were commonly circulating in the natural environment (Figure 1D). All 9 recombinant subtypes of H4 and NA have been found in bird species, with the most common subtype combination being H4N6, followed by H4N8 and H4N2 subtypes. Together, these 3 combinations accounted for 84.34% (3,022/3,583) of all H4 subtype viruses (Figure 1B). We also found that H4N2 viruses mainly infect wild birds, which accounted for 61.15% (181/296) of the total hosts recorded in the database (Figure 1C). However, few studies have studied the biological characteristics of H4N2 viruses in wild birds.

Figure 1.

The prevalence of H4 viruses globally. (A) Numbers of H4 viruses from 1956 to 2022 in the database. (B) H4 and NA recombinant subtypes. (C) The host of H4N2 viruses. (D) The global distribution of H4 viruses.

Prevalence of H4 Subtype Viruses in Wild Birds in Shanghai

From 2019 to 2021, a total of 4,451 samples were collected from wild birds, including 1,112 environmental samples (feces) and 3,339 swab samples (Table 1). The total prevalence of AIVs was 13.97% (n = 622, 622/4,451) (Table 1). Of these AIVs positive samples, 7.40% (n = 46, 46/622) were confirmed to be positive for H4 subtype viruses (Table 1), while 22.51% (n = 140, 140/622) for H5 subtype viruses. The remaining subtypes exhibited comparatively lower percentages: H1 (2.41%), H6 (2.01%), H9 (1.61%), H3 (1.29%), H10 (0.64%), H12 (0.32%), and H11 (0.16%). It was interesting to note that 43 H4 subtypes were H4N2 viruses, and the other 3 NA genes of these H4 subtype strains could not be successfully sequenced due to their low-quality sequences. Forty-six H4 subtype viruses were isolated from migratory waterfowl, including common teal (16), spot-billed duck (14), mandarin duck (5), mallard (5), Eurasian wigeon (2), falcated duck (1), and unknown hosts with feces samples (3) (Table 1). The results indicated H4N2 AIVs had a wide host range among Anseriformes species.

Table 1.

Host information in winter from 2019 to 2021.

| Common name | Scientific name | No. of samples | No. of AIV positive | Prevalence % (95% CI, No. of AIV positive/No. of samples) | No. of H4 positive | Prevalence % (95% CI, No. of H4 positive/No. of AIV positive) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandarin duck | Aix galericulata | 46 | 17 | 36.96 (23.60–52.48) | 5 | 29.41 (11.38–55.95) |

| Eurasian wigeon | Mareca penelope | 96 | 26 | 27.08 (18.75–37.27) | 2 | 7.69 (1.34–2.66) |

| Mallard | Anas platyrhynchos | 211 | 94 | 44.55 (37.77-51.53) | 5 | 5.32 (1.98–12.55) |

| Spot-billed duck | Anas poecilorhyncha | 246 | 105 | 42.68 (36.46–49.13) | 14 | 13.33 (7.74–21.69) |

| Falcated duck | Anas falcata | 22 | 10 | 45.45 (25.07–67.32) | 1 | 10.00 (0.52–45.88) |

| Common teal | Anas crecca | 773 | 190 | 24.58 (21.61–27.80) | 16 | 8.42 (5.04–13.55) |

| Other birds1 | / | 1945 | 113 | 5.81 (4.83–6.97) | 0 | 0 |

| Environment | / | 1112 | 84 | 7.55 (6.10–9.30) | 3 | 3.57 (0.93–10.80) |

| Total | / | 4451 | 622 | 13.97 (12.97–15.03) | 46 | 7.40 (5.52–9.82) |

No H4 subtype of avian influenza was detected in these wild birds.

Sequence Analysis

In this study, a total of 20 H4N2 viruses were chosen as representatives according to their hosts and the cycle threshold (CT) values obtained from real-time PCR for further analysis. These chosen viruses are designated as shown in Supplementary File 1. Full genome sequences of 20 H4N2 viruses have been attained for analysis, including polymerase basic 2 (PB2) gene sequences, polymerase basic 1 (PB1) gene sequences, polymerase acidic (PA) gene sequences, HA gene sequences, nucleoprotein (NP) gene sequences, NA gene sequences, matrix (M) gene sequences, and nonstructural (NS) gene sequence. The sequence data of all isolates have been deposited into the GISAID EpiFlu Database, with the accession number from EPI_ISL_17811764 to EPI_ISL_17811783.

The 8 gene segments of these H4N2 viruses shared a 91.46% to 100% nucleotide identity, and a higher level of nucleotide similarity was observed within the same year compared to those from different years. For example, the HA genes of these H4N2 viruses shared a high level of nucleotide similarity within the same year (98.97% to 100% for 2019, 99.60% for 2020, and 99.80% for 2021), but showed a lower level of sequence identity over the three years (93.14%-100% for 2019-2021). These results indicated that these H4N2 viruses were undergoing a process of evolution and mutations.

The whole genome sequence of the 2019-H4N2 viruses in this study showed a high similarity with a wild bird H4N2 virus (A/wild bird/China/Y13/2019), isolated at the same time and place by another team. Therefore, they were analyzed together in the following studies and designated as 2019-H4N2 viruses. Gene sequence analysis showed that the HA fragments of 2019-H4N2 viruses had a high identity (99.06%–99.80%) with that of the Vietnamese duck H4N6 virus, while the HA genes of two 2020-H4N2 viruses (referred to as 2020-H4N2 viruses) were highly similar to those of an H4N6 Mongolia strain (98.73%–98.91%). The HA genes of 2021-H4N2 viruses (referred to as 2021-H4N2 viruses) shared 98.79% and 98.9% nucleotide identity with those of the H4N2 spot-billed duck AIV circulating in South Korea. For NA fragments, H4N2 viruses were most similar to H6N2 or H5N2 AIVs from China, Japan, and South Korea (97.42%–99.72%) (Supplementary File 2).

For the 6 internal genes, except for the PB1 gene of a strain of H4N2 virus in 2021 (NH21920), all these H4N2 viruses shared more than 98.07% highest nucleotide similarity with those of LPAIV gene pools in the Northeast Asia region, including Vietnam, Korea, Japan, Russia, Mongolia and other regions of China. The PB1 gene of NH21920 displayed high similarities (99.46%) to an H5N8 HPAIV found in a wild duck in Korea (A/wild bird/Korea/H379/2020), suggesting that H4N2 virus might provide internal genes for HPAIV and contributes to the recombination and prevalence of HPAIV (Supplementary File 2).

Phylogenetics and Genotypes Analysis

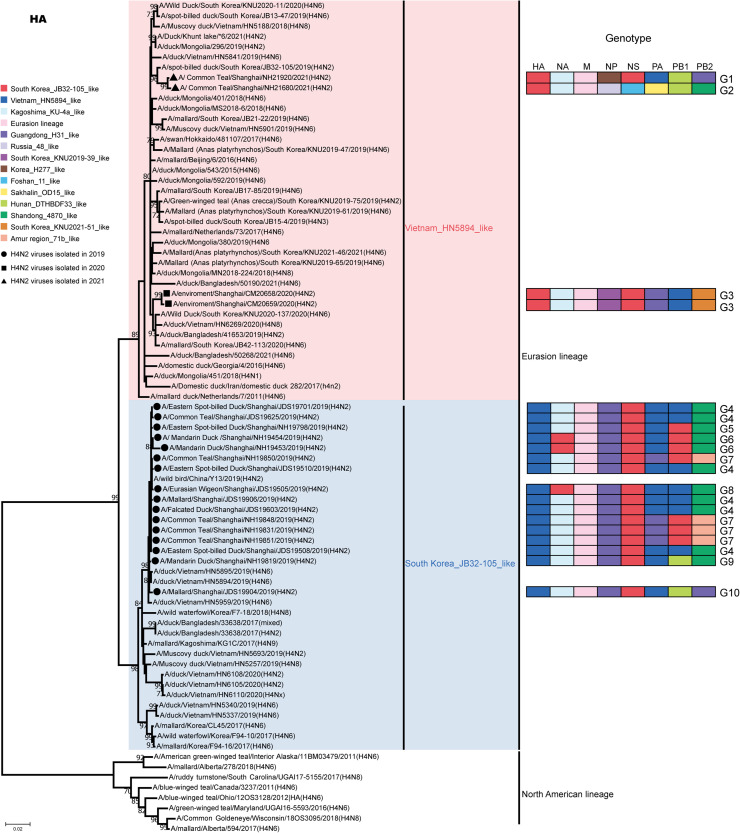

We performed phylogenetic analyses of the whole genomic sequences and showed that these H4N2 viruses were clustered in the Eurasian lineage, with no evidence of intercontinental spread found in this study (Figure 2). In the HA phylogenetic tree, all 2019-H4N2 viruses were closely clustered with the H4N6 virus circulating in Vietnam ducks (A/duck/Vietnam/HN5894/2019) into the Vietnam_HN5894_like group. Two 2020-H4N2 viruses (CM20658 and CM20659) and two 2021-H4N2 viruses (NH21680 and NH21920) were closely clustered with H4N2 northeast Asian strains circulating in wild birds and belonged to South Korea_JB32-105_like group (Figure 2). As for the NA tree, all these H4N2 viruses also could be classified into 2 groups: Kagoshima_KU-4a_like group and South Korea_KNU2019-66_like group. Thirteen 2019-H4N2 viruses, two 2020-H4N2 viruses, and two 2021-H4N2 viruses were clustered into the Kagoshima_KU-4a_like group, and they were closely related to H6N2 viruses from the environment in Japan and H6N2 viruses from wild birds in China. The other three 2019-H4N2 viruses were clustered into South Korea_KNU2019-66_like group, and closely related to H5N2 or H6N2 viruses circulating in the wild bird in South Korea.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic trees of the HA genes of 20 H4N2 isolates from Shanghai, China during 2019 to 2021. The maximum-likelihood (ML) phylogenetic trees were constructed in MEGA software version 7.0. The bootstrap values were calculated on 1,000 replicates, and values less than 70% are not shown. Black solid circles represent H4N2 viruses isolated in 2019, black solid squares represent H4N2 viruses isolated in 2020, and black solid triangles represent H4N2 viruses isolated in 2021. The genotypes of the 8 genes are shown on the right side of the graph, and the different colors represent different groups.

Phylogenetic analysis of the internal genes indicated that all these H4N2 viruses belonged to 2 to 4 different groups in the Eurasian lineage, except for M genes (Supplementary Figure 1). The M genes of all H4N2 viruses detected in this study shared high nucleotide identity (>98%) and clustered into 1 group in the phylogenetic tree. The PB2 and NP genes of these H4N2 viruses were clustered into 4 groups, the PA and PB1 genes were clustered into 3 groups, and the NS genes were clustered into 2 groups. The NP phylogeny analysis revealed that sixteen 2019-H4N2 viruses were closely related to a domestic duck H3N8 recombinant virus in Guangdong and belonged to the Guangdong_H31_like group (Li et al., 2021), suggesting that the internal genes of the H4N2 viruses might undergo recombination with other subtypes of viruses. Two 2020-H4N2 viruses fell into a South Korea_ KNU2019-39_like group, which were closely related to wild bird H9N2 viruses that circulated in Korea. Two 2021-H4N2 viruses formed 2 separate groups: one (NH21680) was grouped with a Russia_48_like strain (H3N8), and the other (NH21920) was grouped with a Korea_H277_like strain (H5N3). Excluding NH21680, the NS tree strains clustered into a Foshan_11_like strain (H3N2), while all the other 19 H4N2 viruses were clustered into a Jiangxi_JJCHBC76_like (H1N1) strain. For the PA tree, twelve 2019-H4N2 and one 2021-H4N2 (NH21920) viruses clustered into a Vietnam_HN5894_like strain, which were closely related to domestic duck H4N6 virus circulating in Vietnam. Four 2019-H4N2 viruses and two 2020-H4N2 viruses clustered into a Guangdong_H31_like strain (H3N8), and one 2021-H4N2 virus (NH21680) clustered into a Sakhalin_OD15_like group (H3N8). The PB2 trees formed 4 groups: eleven 2019-H4N2 viruses and NH21690 virus clustered into a Shandong_4870_like strain (H9N2); four 2019-H4N2 viruses clustered into an Amur region_71b_like strain (H3N8); one 2019-H4N2 virus and NH21920 virus clustered into a Jiangxi_JJCHBCT6_like strain (H6N5); and two 2020-H4N2 viruses clustered into a South Korea_ KNU2021-51_like strain (H8N4). For the PB1 tree, seven 2019-H4N2 viruses clustered into a South Korea_JB32-105_like strain (H4N2); seven 2019-H4N2 viruses and two 2020-H4N2 viruses clustered into a Vietnam_HN5894_like strain (H4N6); and two 2019-H4N2 viruses and two 2021-H4N2 viruses clustered into a Hunan_DTHBDF33_like strain (H9N2). Among them, NH21920 was specifically clustered with a Northeast Asian HPAIV H5N1, reflecting its potential to produce novel reassortant viruses that pose a threat to wild birds and poultry.

According to nucleotide similarity (>97%), tree topology structure, and bootstrap values (>85%), these 20 viruses were classified into 10 genotypes. Sixteen viruses in 2019 were classified into 7 genotypes (G1–G7), the two 2020-H4N2 viruses belonged to the same genotype (G8), and two 2021-H4N2 viruses belonged to 2 different genotypes (G9 and G10) (Figure 2). Due to the genetic recombination of the virus, there were no H4N2 viruses isolated in 2 different years belonging to the same genotype, indicating that the H4N2 virus continued to undergo recombinant and evolve in wild birds. These results also suggested that genetically divergent H4N2 viruses were most likely introduced through reassortment in domestic poultry and wild birds along migratory flyways (Figure 2).

Molecular Characterization of H4N2

Molecular characteristics of H4N2 isolates showed that all H4N2 isolates were LPAIVs, with IPEKASR↓GLF at the HA cleavage site and a monobasic amino acid. Previous research has shown that amino acids at positions Q226 and G228 are critical for the receptor-binding transition of AIVs (Song et al., 2017). However, we did not find any change at these 2 sites in all H4N2 viruses, indicating that they retained the avian-like receptor-binding preference (Naeve et al., 1984; Matrosovich et al., 2000). The absence of E119G and H274N mutations on NA indicated that there were no neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs) resistance mutations (Tepper et al., 2020). No amino acid deletions were observed in the NA stalk region. Mutations involved in M2 proteins were also not observed in these strains, suggesting that these viruses may be sensitive to M2 ion channel blockers. The substitutions of E627K (Schat et al., 2012; Subbarao et al., 1993) and D701N (Puthavathana et al., 2005) in PB2 proteins associated with enhanced virulence to mammals were not found in these H4N2 strains.

DISCUSSION

As a zoonotic disease, avian influenza poses potential threats to human health, wildlife conservation, and the economic stability of the farming industry. Therefore, active surveillance of avian influenza is crucial in establishing the first barrier of defense for ecological health. The H4 subtype of AIVs is frequently isolated from wild birds worldwide. The presence of low pathogenic H4 subtype AIVs from migratory birds for 3 consecutive years in this study further confirms that the H4 subtype is one of the most common subtypes of AIVs in wild birds throughout Eurasia (Olsen et al., 2006; Kang et al., 2010). Although the exact pattern of transmission for low pathogenic avian influenza H4N2 is still unknown, its transmission may be closely related to the migration route of wild birds, similar to HPAIV H5N1 (Verhagen et al., 2021).

Wild birds are considered to be the natural hosts for AIVs. We detected H4N2 viruses in swab samples from 6 different species of ducks, including mandarin ducks, Eurasian wigeons, mallards, spot-billed ducks, falcated ducks, and common teals. These wild ducks used different migration patterns, as mallards adopt a “long-stay and short-travel” migration strategy and short-distance migration patterns (Yamaguchi et al., 2008), while common teal used a typical chain migration strategy and long-distance migration patterns. Therefore, they may come from different breeding habitats and intermittently stay in various areas along their migration routes, particularly where the intertwined migratory routes are. The results indicated that the H4N2 virus could infect a wide range of hosts in migratory ducks, and had the potential to spread the virus to other contacted wild birds or domestic poultry along their migration route, resulting in cross-regional transmission of AIVs.

This study has demonstrated that H4 viruses primarily infect Anseriformes, whereas no evidence of H4 virus infection was detected in Charadriiformes, which are recognized as one of the natural reservoirs for AIVs (Stallknecht et al., 1988). Many articles have also reported a higher prevalence of H4 avian influenza in Anseriformes compared to Charadriiformes (Hurtado et al., 2016; Sharshov et al., 2017). The possible reason is that the samples collected from Charadriiformes were limited. Sampling bias needed to be eliminated in future epidemiological surveys. Additionally, our study found a higher prevalence of AIVs in swabs (VanDalen et al., 2010) compared to fecal and water samples (Ahrens et al., 2023), which may be attributed to the lower viral load and quality in these types of samples.

Current research has demonstrated the H4 subtype of AIVs possesses interspecies transmission potential. As early as 1999, avian influenza H4N6 subtype infection in pigs under natural conditions has been reported (Karasin et al., 2000). Additionally, sequence analysis of H4 subtype avian influenza has revealed the presence of multiple basic amino acids at 345 and 346 in the H4N2 sequence of a farm quail strain, with a cleavage motif PEKRRTR/G (Wong et al., 2014; Gischke et al., 2021). Several studies have reported that H4N2 viruses have acquired the ability to bind α-2,6 sialic acid (Bateman et al., 2008; Liang et al., 2016), which is the mammalian receptor, and deletion of the H4 viruses NA stalk region in poultry has been identified (Reid et al., 2018), which is associated with virulence and pathogenesis of viruses. However, no mutations were detected at key sites that alter the inherent host binding specificity, enhance pathogenicity, or increase drug resistance in the sequences of 20 H4N2 viruses. We cannot exclude the possibility that other sites may enhance the pathogenicity of H4 subtype, therefore further monitoring and biological characterization are still necessary.

All 8 genes of 20 H4N2 viruses from 2019 to 2021 were clustered into Eurasian lineages. Phylogenetical analysis revealed that these 8 genes of H4N2 viruses were closely related to AIVs from East and Northeast Asia along migratory birds’ flyways, including Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Mongolia, Russia, and many other countries. These findings suggested these viruses may originate from the same ancestors. We also found there are at least 10 different genotypes of H4N2 viruses prevalent in Shanghai. These findings suggested that these H4N2 viruses isolated in this study had undergone intricate cross-regional recombination, particularly within the PA, NP, PB1, and PB2 genes. (Wille et al., 2022b) sequenced 248 H4 viruses during long-term surveillance (2002–2009) in Sweden, found 88 genome constellations of these viruses, and observed the lineage replacement in different years. The circulation of LPAIVs in wild birds plays a crucial role in providing an increased gene pool. Our studies also demonstrated that the PB1 gene of an H4N2 virus isolated in 2021 could provide the internal gene for HPAIV H5N8. This phenomenon was also observed in H9N2, which served as an internal gene donor for the H5N1 subtype of AIV that caused human infections in 1997 (Guan et al., 2000). Genetic diversity has been observed in H4N2 avian influenza viruses present in migratory birds, indicating the possibility of emergence of novel strains and increased adaptability to a wider range of hosts.

In conclusion, this study suggested that H4N2 viruses exhibited abundant genotypes and persisted in wild birds in Shanghai with a wide host distribution, primarily in the order of Anseriformes. All 20 H4N2 strains were low pathogenic avian influenza and had no mutations at key sites. Eight gene fragments of these viruses exhibited high similarity to avian influenza strains in the East Asia-Australasia migration pathway and could provide internal genes for HPAIV H5N8. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct long-term surveillance and analysis on the prevalence, molecular characteristics, phylogeny, and recombination of H4N2 viruses due to their potential risk to public health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32172943), the Shanghai Science and Technology Committee Project (grant no. 18DZ2293800), and the Shanghai Wildlife-borne Infectious Disease Monitoring Program (11301-412311-23098). We thank Shanghai Forestry Station for field sampling assistance.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.psj.2023.102948.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

REFERENCES

- Abente E.J., Gauger P.C., Walia R.R., Rajao D.S., Zhan J., Harmon K.M., Killian M.L., Vincent A.L. Detection and characterization of an H4N6 avian-lineage influenza A virus in pigs in the Midwestern United States. Virology. 2017;511:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2017.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens A.K., Selinka H.C., Wylezich C., Wonnemann H., Sindt O., Hellmer H.H., Pfaff F., Höper D., Mettenleiter T.C., Beer M., Harder T.C. Vol. 11. 2023. Investigating environmental matrices for use in avian influenza virus surveillance-surface water, sediments, and avian fecal samples. (Microbiol. Spectr). e0266422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A.C., Busch M.G., Karasin A.I., Bovin N., Olsen C.W. Amino acid 226 in the hemagglutinin of H4N6 influenza virus determines binding affinity for alpha2,6-linked sialic acid and infectivity levels in primary swine and human respiratory epithelial cells. J. Virol. 2008;8:8204–8209. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00718-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi Y., Chen Q., Q.Wang J.Chen, Jin T., Wong G., Quan C., Liu J., Wu J., Yin R., Zhao L., Li M., Ding Z., Zou R., Xu W., Li H., Wang H., Tian K., Fu G., Huang Y., Shestopalov A., Li S., Xu B., Yu H., Luo T., Lu L., Xu X., Luo Y., Liu Y., Shi W., Liu D., Gao G.F. Genesis, evolution and prevalence of H5N6 avian influenza viruses in China. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;2:810–821. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busquets N., Alba A., Napp S., Sánchez A., Serrano E., Rivas R., Núñez J.I., Maj N. Influenza A virus subtypes in wild birds in North-Eastern Spain (Catalonia) Virus Res. 2010;149:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui P., Shi J., Wang C., Zhang Y., Xing X., Kong H., Yan C., Zeng X., Liu L., Tian G., Li C., Deng G., Chen H. Global dissemination of H5N1 influenza viruses bearing the clade 2.3.4.4b HA gene and biologic analysis of the ones detected in China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2022;11:1693–1704. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2088407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diskin E.R., Friedman K., Krauss S., Nolting J.M., Poulson R.L., Slemons R.D., Stallknecht D.E., Webster R.G., Bowman A.S., Heise M.T. Subtype diversity of influenza A virus in North American waterfowl: a multidecade study. J. Virol. 2020;94 doi: 10.1128/JVI.02022-19. e02022-02019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donis R.O., Bean W.J., Kawaoka Y., Webster R.G. Distinct lineages of influenza virus H4 hemagglutinin genes in different regions of the world. Virology. 1989;169:408–417. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouchier R.A.M., Munster V., Wallensten A., Bestebroer T.M., Herfst S., Smith D., Rimmelzwaan G.F., Olsen B., Osterhaus A.D.M.E. Characterization of a novel influenza A virus hemagglutinin subtype (H16) obtained from black-headed gulls. J. Virol. 2005;79:2814–2822. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2814-2822.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass J.D., Kellogg H.K., Hill N.J., Puryear W.B., Nutter F.B., Runstadler J.A. Epidemiology and ecology of influenza A viruses among wildlife in the Arctic. Viruses. 2022;14:1531. doi: 10.3390/v14071531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gischke M., Bagato O., Breithaupt A., Scheibner D., Blaurock C., Vallbracht M., Karger A., Crossley B., Veits J., Böttcher-Friebertshäuser E., Mettenleiter T.C., Abdelwhab E.M. The role of glycosylation in the N-terminus of the hemagglutinin of a unique H4N2 with a natural polybasic cleavage site in virus fitness in vitro and in vivo. Virulence. 2021;12:666–678. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2021.1881344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y., Shortridge K.F., Krauss S., Chin P.S., Dyrting K.C., Ellis T.M., Webster R.G., Peiris M. H9N2 influenza viruses possessing H5N1-like internal genomes continue to circulate in poultry in southeastern China. J. Virol. 2000;74:9372–9380. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.20.9372-9380.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He G., Zhou L., Zhu C., Shi H., Li X., Wu D., Liu J., Lv J., Hu C., Li Z., Wang Z., Wang T. Identification of two novel avian influenza A (H5N6) viruses in wild birds, Shanghai, in 2016. Vet. Microbiol. 2017;208:53–57. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw V.S., Bean W.J., Webster R.G., Rehg J.E., Fiorelli P., Early G., Geraci J.R., St Aubin D.J. Are seals frequently infected with avian influenza viruses? J. Virol. 1984;51:863–865. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.3.863-865.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann E., Stech J., Guan Y., Webster R.G., Perez D.R. Universal primer set for the full-length amplification of all influenza A viruses. Arch. Virol. 2001;146:2275–2289. doi: 10.1007/s007050170002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Khan M.I., Mandoiu I. Neuraminidase subtyping of avian influenza viruses with PrimerHunter-designed primers and quadruplicate primer pools. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado R., de Azevedo-Júnior S.M., Vanstreels R.E.T., Fabrizio T., Walker D., Rodrigues R.C., Seixas M.M.M., de Araújo J., Thomazelli L.M., Ometto T.L., Webby R.J., Webster R.G., Jerez J.A., Durigon E.L. Surveillance of avian influenza virus in aquatic birds on the Brazilian Amazon Coast. EcoHealth. 2016;13:813–818. doi: 10.1007/s10393-016-1169-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H.M., Choi J.G., Kim K.I., Park H.Y., Park C.K., Lee Y.J. Genetic and antigenic characteristics of H4 subtype avian influenza viruses in Korea and their pathogenicity in quails, domestic ducks and mice. J. Gen. Virol. 2013;94:30–39. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.046581-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H.M., Jeong O.M., Kim M.C., Kwon J.S., Paek M.R., Choi J.G., Lee E.K., Kim Y.J., Kwon J.H., Lee Y.J. Surveillance of avian influenza virus in wild bird fecal samples from South Korea, 2003-2008. J. Wildl. Dis. 2010;46:878–888. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-46.3.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasin A.I., Brown I.H., Carman S., Olsen C.W. Isolation and characterization of H4N6 avian influenza viruses from pigs with pneumonia in Canada. J. Virol. 2000;74:9322–9327. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.19.9322-9327.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayali G., Barbour E., Dbaibo G., Tabet C., Saade M., Shaib H.A., Debeauchamp J., Webby R.J. Evidence of infection with H4 and H11 avian influenza viruses among Lebanese chicken growers. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayali G., Ortiz E.J., Chorazy M.L., Gray G.C. Evidence of previous avian influenza infection among US turkey workers. Zoonoses Public Health. 2010;57:265–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2009.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G.S., Kim T.S., Son J.S., Lai V.D., Park J.E., Wang S.J., Jheong W.H., Mo I.P. The difference of detection rate of avian influenza virus in the wild bird surveillance using various methods. J. Vet. Sci. 2019;20:e56. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2019.20.e56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G., Shin H.M., Kim H.R., Kim Y. Effects of host and pathogenicity on mutation rates in avian influenza A viruses. Virus Evol. 2022;8 doi: 10.1093/ve/veac013. veac013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Xie S., Jiang X., Li Z., Xu L., Wen K., Zhang M., Liao M., Jia W. Emergence of one novel reassortment H3N8 avian influenza virus in China, originating from North America and Eurasia. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2021;91 doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2021.104782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang L., Deng G., Shi J., Wang S., Zhang Q., Kong H., Gu C., Guan Y., Suzuki Y., Li Y., Jiang Y., Tian G., Liu L., Li C., Chen H. Genetics, receptor binding, replication, and mammalian transmission of H4 avian influenza viruses isolated from live poultry markets in China. J. Virol. 2016;90:1455–1469. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02692-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M., He S., Walker D., Zhou N., Perez D.R., Mo B., Li F., Huang X., Webster R.G., Webby R.J. The influenza virus gene pool in a poultry market in South Central China. Virology. 2003;305:267–275. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matrosovich M., Tuzikov A., Bovin N., Gambaryan A., Klimov A., Castrucci M.R., Donatelli I., Kawaoka Y. Early alterations of the receptor-binding properties of H1, H2, and H3 avian influenza virus hemagglutinins after their introduction into mammals. J. Virol. 2000;74:8502–8512. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8502-8512.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeve C.W., Hinshaw V.S., Webster R.G. Mutations in the hemagglutinin receptor-binding site can change the biological properties of an influenza virus. J. Virol. 1984;51:567–569. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.2.567-569.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen B., Munster V.J., Wallensten A., Waldenström J., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Fouchier R.A.M. Global patterns of influenza A virus in wild birds. Science. 2006;312:384–388. doi: 10.1126/science.1122438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthavathana P., Auewarakul P., Charoenying P.C., Sangsiriwut K., Pooruk P., Boonnak K., Khanyok R., Thawachsupa P., Kijphati R., Sawanpanyalert P. Molecular characterization of the complete genome of human influenza H5N1 virus isolates from Thailand. J. Gen. Virol. 2005;86:423–433. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80368-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid S.M., Brookes S.M., Núñez A., Banks J., Parker C.D., Ceeraz V., Russell C., Seekings A., Thomas S.S., Puranik A., Brown I.H. Detection of non-notifiable H4N6 avian influenza virus in poultry in Great Britain. Vet. Microbiol. 2018;224:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schat K.A., Bingham J., Butler J.M., Chen L.M., Lowther S., Crowley T.M., Moore R.J., Donis R.O., Lowenthal J.W. Role of position 627 of PB2 and the multibasic cleavage site of the hemagglutinin in the virulence of H5N1 avian influenza virus in chickens and ducks. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharshov K.A., Yurlov A.K., Li X., Wang W., Li L., Bi Y., Liu W., Saito T., Ogawa H., Shestopalov A.M. Avian influenza virus ecology in wild birds of Western Siberia. Avian Res. 2017;8:12. [Google Scholar]

- Song H., Qi J., Xiao H., Bi Y., Zhang W., Xu Y., Wang F., Shi Y., Gao G.F. Avian-to-human receptor-binding adaptation by influenza A virus hemagglutinin H4. Cell Rep. 2017;2:1201–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallknecht D.E., Shane S.M. Host range of avian influenza virus in free-living birds. Vet. Res. Commun. 1988;12:125–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00362792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbarao E.K., London W., Murphy B.R. A single amino acid in the PB2 gene of influenza A virus is a determinant of host range. J. Virol. 1993;67:1761–1764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.1761-1764.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L., Tang W., Li X., Hu C., Wu D., Wang T., He G. Avian influenza virus prevalence and subtype diversity in wild birds in Shanghai, China, 2016–2018. Viruses. 2020;12:1031. doi: 10.3390/v12091031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper V., Nykvist M., Gillman A., Skog E., Wille M., Lindström H.S., Tang C., Lindberg R.H., Lundkvist Å., Järhult J.D. Influenza A/H4N2 mallard infection experiments further indicate zanamivir as less prone to induce environmental resistance development than oseltamivir. J. Gen. Virol. 2020;101:816–824. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanDalen K.K., Franklin A.B., Mooers N.L., Sullivan H.J., Shriner S.A. Shedding light on avian influenza H4N6 infection in mallards: modes of transmission and implications for surveillance. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh D., Poen M.J., Bestebroer T.M., Scheuer R.D., Vuong O., Chkhaidze M., Machablishvili A., Mamuchadze J., Ninua L., Fedorova N.B., Halpin R.A., Lin X., Ransier A., Stockwell T.B., Wentworth D.E., Kriti D., Dutta J., Bakel H.V., Puranik A., Slomka M.J., Essen S., Brown I.H., Fouchier R.A.M., Lewis N.S., Schultz-Cherry S. Avian influenza viruses in wild birds: virus evolution in a multihost ecosystem. J. Virol. 2018;92 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00433-18. e00433-00418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen J.H., Fouchier R.A.M., Lewis N. Highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses at the wild–domestic bird interface in Europe: future directions for research and surveillance. Viruses. 2021;13:212. doi: 10.3390/v13020212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wille M., Grillo V., Ban De Gouvea Pedroso S., Burgess G.W., Crawley A., Dickason C., Hansbro P.M., Hoque M.A., Horwood P.F., Kirkland P.D., Kung N.Y.-H., Lynch S.E., Martin S., McArthur M., O'Riley K., Read A.J., Warner S., Hoye B.J., Lisovski S., Leen T., Hurt A.C., Butler J., Broz I., Davies K.R., Mileto P., Neave M.J., Stevens V., Breed A.C., Lam T.T.Y., Holmes E.C., Klaassen M., Wong F.Y.K. Australia as a global sink for the genetic diversity of avian influenza A virus. PLoS Pathog. 2022;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wille M., Tolf C., Latorre-Margalef N., Fouchier R.A.M., Halpin R.A., Wentworth D.E., Ragwani J., Pybus O.G., Olsen B., Waldenström J. Evolutionary features of a prolific subtype of avian influenza A virus in European waterfowl. Virus Evol. 2022;8 doi: 10.1093/ve/veac074. veac074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong S.S., Yoon S.W., Zanin M., Song M.S., Oshansky C., Zaraket H., Sonnberg S., Rubrum A., Seiler P., Ferguson A., Krauss S., Cardona C., Webby R.J., Crossley B. Characterization of an H4N2 influenza virus from Quails with a multibasic motif in the hemagglutinin cleavage site. Virology. 2014;468-470:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi N., Hiraoka E., Fujita M., Hijikata N., Ueta M., Takagi K., Konno S., Okuyama M., Watanabe Y., Osa Y., Morishita E., Tokita K.I., Umada K., Fujita G., Higuchi H. Spring migration routes of mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) that winter in Japan, determined from satellite telemetry. Zool. Sci. 2008;25:875–881. doi: 10.2108/zsj.25.875. 877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Zhu W., Li X., Chen M., Wu J., Yu P., Qi S., Huang Y., Shi W., Dong J., Zhao X., Huang W., Li Z., Zeng X., Bo H., Chen T., Chen W., Liu J., Zhang Y., Liang Z., Shi W., Shu Y., Wang D. Genesis and spread of newly emerged highly pathogenic H7N9 avian viruses in mainland China. J. Virol. 2017;91 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01277-17. e01277-01217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong D.L., Liu Y., Low B.W., EspaÑOla C.P., Choi C.Y., Kawakami K. Migratory songbirds in the East Asian-Australasian Flyway: a review from a conservation perspective. Bird Conserv. Int. 2015;25:1–37. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.