Abstract

The successful use of DNA amplification for the detection of tuberculous mycobacteria crucially depends on the choice of the target sequence, which ideally should be present in all tuberculous mycobacteria and absent from all other bacteria. In the present study we developed a PCR procedure based on the intergenic region (IR) separating two genes encoding a recently identified mycobacterial two-component system named SenX3-RegX3. The senX3-regX3 IR is composed of a novel type of repetitive sequence, called mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units (MIRUs). In a survey of 116 Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains characterized by different IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphisms, 2 Mycobacterium africanum strains, 3 Mycobacterium bovis strains (including 2 BCG strains), and 1 Mycobacterium microti strain, a specific PCR fragment was amplified in all cases. This collection included M. tuberculosis strains that lack IS6110 or mtp40, two target sequences that have previously been used for the detection of M. tuberculosis. No PCR fragment was amplified when DNA from other organisms was used, giving a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 100% in the confidence limit of this study. The numbers of MIRUs were found to vary among strains, resulting in six different groups of strains on the basis of the size of the amplified PCR fragment. However, the vast majority of the strains (approximately 90%) fell within the same group, containing two 77-bp MIRUs followed by one 53-bp MIRU.

Tuberculosis still remains a major public health problem worldwide, with an estimated 1.7 million people infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (37). Furthermore, the number of tuberculosis patients has increased in the United States and Europe in recent years, mainly in high-risk populations, such as human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients, people who are chronic alcoholics, homeless people, and people who are drug abusers (1). The advancing age of the population and a general neglect of tuberculosis control programs in many countries also contribute to the increasing incidence of tuberculosis (7, 14). In addition, drug-resistant M. tuberculosis strains have emerged, which further complicates tuberculosis control programs (4–6, 25).

An essential element in the control of tuberculosis is the rapid, sensitive, and specific identification of the causative agent. Until now, diagnosis is largely based on clinical signs, radiological examination, tuberculin tests, sputum examination under the microscope, or culture for mycobacteria. Tuberculin tests lack specificity and only give an indication of previous exposure to mycobacteria. Direct microscopic examination of sputum is neither specific nor sensitive enough, and mycobacterial isolation is time-consuming. As an alternative to these classical methods, new nucleic acid-based technologies show promise as a more rapid, sensitive, and specific means of identification of mycobacteria. Two commercial standardized nucleic acid-based amplification techniques have been reported to yield reliable results within 5 to 7 h of sample processing: Roche Amplicor MTB (Roche Diagnostic Systems, Somerville, N.J.) and Gen-Probe AMTB (Gen-Probe Inc., San Diego, Calif.). The amplified target is part of the 16S rRNA gene which is common to all the mycobacteria. The discrimination between the members of the M. tuberculosis complex, comprising M. tuberculosis, Mycobacterium bovis, Mycobacterium africanum, and Mycobacterium microti, and the other mycobacteria requires an additional step that involves DNA hybridization (2, 3, 8, 11, 15, 17, 26, 33, 43, 49, 51).

Single-step PCR procedures have also been developed in an effort to identify the members of the M. tuberculosis complex. The target most widely used in these procedures is the insertion sequence IS6110, either alone (10, 18, 21, 34, 45) or in association with the mtp40 gene (13, 23, 28). However, false-positive and false-negative results have been reported when IS6110 (18–20, 27, 28, 31, 34, 39, 48, 52) or mtp40 (28, 50) was used as the target sequence. So far, no single target sequence has provided 100% sensitivity and a total absence of false-positive results when used alone.

In this report we describe a new DNA target sequence that is present in all strains of the M. tuberculosis complex tested and that is absent from all other mycobacterial strains tested. This sequence is based on the intergenic region (IR) of the genes coding for a recently identified mycobacterial two-component system, named SenX3-RegX3 (44). This IR is composed of a novel type of repetitive DNA called mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units (MIRUs). The number of MIRUs found in the senX3-regX3 IR is variable, but there is at least one strictly conserved 77-bp element.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

M. tuberculosis 2296207 was described elsewhere (44). M. tuberculosis S200, the 2 M. africanum strains, and 109 clinical M. tuberculosis isolates were obtained from the Centre Hospitalier Régional of Lille, France. The two M. tuberculosis strains lacking mtp40 (strains 912609 and 912761) were obtained from B. B. Plikaytis from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, Ga.), and the three M. tuberculosis strains lacking IS6110 isolated in Vietnam (strains V.729, V.761, and V.808) were kindly provided by G. Marshall (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France), as were M. bovis AN5 and M. microti ATCC 19422. The Glaxo M. bovis BCG vaccine strain was provided by M. Lagranderie (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France), and the vaccine strain M. bovis BCG 1173P2 was obtained from the World Health Organization collection in Stockholm, Sweden. The following 11 atypical mycobacteria used were clinical isolates obtained from the Institut Pasteur de Lille culture collection: M. aurum, M. avium, M. chelonae, M. flavescens, M. fortuitum, M. kansasii, M. marinum, M. scrofulaceum, M. smegmatis, M. terrae, and M. xenopi. Two Streptomyces strains (Streptomyces cacaoi and Streptomyces sp. strain R39) were a gift of J. Dusart (Université de Liège, Liège, Belgium). Escherichia coli TG1 was purchased from Stratagene (Ozyme, Montigny-Le-Bretonneux, France), and Bordetella pertussis BPSM was described earlier (32).

Chromosomal DNA isolation.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from the Streptomyces strains as described by Chater et al. (9). Isolation of the chromosomal DNA of E. coli TG1 and B. pertussis BPSM was done as described by Hull et al. (24). Mycobacteria were grown in 100 ml of Sauton medium (41) and were harvested by centrifugation (2,000 × g for 30 min). After centrifugation they were resuspended in 10 ml of buffer P (0.4 M saccharose, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 4 mg of lysozyme [Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.] per ml) and were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The protoplasts were recovered by centrifugation (2,000 × g for 20 min) and lysed by incubating them for 1 h at 60°C in 6 ml of buffer L (10 mM NaCl, 6% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 500 μg of proteinase K [Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany] per ml). After the addition of 1.5 ml of 5 M NaCl, the suspension was centrifuged (16,000 × g for 20 min), and the supernatant was subjected to phenol-chloroform extraction. The DNA was precipitated with isopropanol, resuspended, treated with RNase, extracted with phenol-chloroform and chloroform, and precipitated with ethanol. The final pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of double-distilled water. The concentration of the DNA was estimated by determining the optical density at 260 nm and was generally about 0.33 μg/μl.

Amplification of the senX3-regX3 intergenic region.

The sequences of the two primers used for the amplification of the senX3-regX3 IR were 5′-GCGCGAGAGCCCGAACTGC-3′ (C5) and 5′-GCGCAGCAGAAACGTCAGC-3′ (C3). The PCR (40) was carried out in a thermal reactor (Perkin-Elmer Corporation, Foster City, Calif.) by incubating 1 μl of chromosomal DNA (approximately 0.33 μg) with the following mixture (100 μl total): 170 pmol of oligonucleotides C5 and C3, 50 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Pharmacia Biotech, Sollentuna, Sweden), 50 μM tetramethylammonium chloride (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), enzyme buffer, and 1 U of Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). After a 3-min incubation at 94°C, the amplification was performed for 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 65°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. After the last cycle the samples were incubated for 10 min at 72°C. Negative controls contained the PCR mixture without the template DNA. The two positive controls contained pRegX3Mt1 or pRegX3Bc1 as template DNA; the two plasmids contained the complete senX3-regX3 operons of either M. tuberculosis 2296207 or BCG 1173P2, as described previously (44).

To amplify M. tuberculosis DNA directly from seeded sputum, fresh sputum, negative for M. tuberculosis, was first seeded with 10-fold serial dilutions of M. tuberculosis (5 × 106 to 1 × 50 CFU/ml) as described previously (16). A total of 100 μl of seeded sputum was then mixed with 100 μl of lysis solution containing 15% Chelex 100 (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.), 0.1% SDS, 1% Nonidet P-40, and 1% Tween 20. The mixture was then incubated at 95°C for 20 min and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant was harvested. Five microliters was used in the PCR mixture, and amplification was as described above.

Multiplex PCR.

The two targets for the multiplex PCR were the senX3-regX3 IR and a 997-bp portion of the 16S rRNA gene. The specific primers corresponding to the 16S rRNA gene had the following sequences: 5′-CACATGCAAGTCGAACGGAAAGG-3′ (KY18) and 5′-CCTGCACACAGGCCACAAGGGAA-3′ (KY98). They hybridized to nucleotides 15 to 37 and 999 to 1012 of the 16S rRNA gene, respectively (38). For the multiplex PCR these two primers were used in conjunction with primers C5 and C3 (described above). The PCR was performed in a final volume of 100 μl as described above, except that 70 pmol of primers KY18 and KY98 and 43 pmol of primers C5 and C3 were used and that the samples were subjected to 40 cycles with annealing steps at 58°C for 90 s and extension steps at 72°C for 2 min.

Analysis of the senX3-regX3 IR PCR product.

Ten microliters of each PCR product was subjected to electrophoresis with a 2.5% agarose gel, and the products were visualized with ethidium bromide. The lengths of the PCR products were estimated by comparison with the 1-kb DNA ladder molecular size marker (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, Cergy Pontoise, France) by using the algorithm described by Schaffer and Sederoff (42).

Hybridization analyses.

Two oligonucleotides (5′-AAACACGTCGCGGCTAATCA-3′ and 5′-CCTCAAAGCCCTCCTTGCGC-3′) were used to amplify part of the senX3-regX3 two-component system operon including the IR from M. tuberculosis 2296207. The PCR fragment was cloned into the SmaI site of pBluescript KS− (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). The resulting plasmid was called pRegX3Mt2 and was propagated in E. coli TG1. After isolation of pRegX3Mt2 from this strain, the M. tuberculosis 2296207 senX3-regX3 IR was obtained by digestion of this plasmid with EcoRI and BamHI and purification of the resulting 491-bp DNA fragment by agarose gel electrophoresis and electroelution. This DNA fragment was then further digested with BsrI and AluI yielding a 221-bp DNA fragment corresponding to the M. tuberculosis 2296207 senX3-regX3 IR. This fragment was again purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and electroelution and was labeled by random priming with the digoxigenin-dUTP (DIG) labeling kit (kit catalog no. 1093657; Boehringer Mannheim) as recommended by the supplier. The DIG-labeled probe was then used for the detection of specific DNA after its binding to a positively charged nylon membrane (Boehringer Mannheim) by methods described by Boehringer Mannheim. Briefly, the DIG-labeled probe was denatured by boiling for 5 min and was added to the prehybridization buffer, and the mixture was then incubated overnight at 68°C with the nylon membrane containing the DNA fragments to be analyzed and previously incubated at 68°C in prehybridization buffer (5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 0.1% N-laurylsarcosine, 0.02% SDS, and 1% blocking reagent). The membrane was then washed twice for 5 min each time in 2× SSC–0.1% SDS at room temperature and twice for 15 min each time in 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS at 68°C. The hybridized probe was immunodetected with anti-digoxigenin-alkaline phosphatase and Fab fragments and was then visualized with the disodium 3-(4-methoxspiro{1,2-dioxetane-3,2′-(5′-chloro)tricyclo [3.3.1.13.7]decan-4-yl)phenylphosphate chemiluminescence substrate.

Cloning and sequencing of the senX3-regX3 IR PCR products.

The Zero background/kan cloning kit was used (Invitrogen Corporation, San Diego, Calif.) to clone the senX3-regX3 IR PCR products. The PCR products were first subjected to phenol-chloroform and chloroform extractions. After ethanol precipitation in the presence of 300 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.2), the DNA fragments were ligated into the pZero plasmid previously digested with EcoRV as described by the supplier. Competent E. coli TOP 10F′ (Invitrogen Corporation) was transformed by electroporation with the ligation mixtures and was then plated onto Luria-Bertani agar containing 50 μg of kanamycin per ml and 1 mM isopropylβ-d-thiogalactopyranoside. After isolation of the plasmids, the presence of inserts in the pZero derivatives was verified by NsiI digestion followed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The Nucleobond AX kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) was used to purify the recombinant plasmids for sequencing purposes.

The senX3-regX3 IR PCR products inserted into pZero were sequenced with the universal and reverse primers and the T7 sequencing kit from Pharmacia Biotech (Uppsala, Sweden). Sequencing reactions were carried out with [35S] dATP (Amersham International, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom), and the reaction products were subjected to electrophoresis with 8% polyacrylamide gels.

RFLP analyses.

IS6110-based restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analyses were performed by previously described methods (46). Briefly, M. tuberculosis DNA was extracted, digested with PvuII, subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis, Southern blotted, and hybridized with an 868-bp fragment of IS6110 generated by PCR. The probe was labeled by using the enhanced chemiluminescence gene detection system (Amersham International). The fingerprint patterns of the isolates were compared both by computer-assisted analyses (Gel Compar; Applied Maths) and by visual examination. The distances between two fingerprint patterns were calculated according to the Dice index. The algorithm used to produce the dendrogram from these distances was the unweighted pair group method of analysis.

RESULTS

PCR amplification of the senX3-regX3 IR.

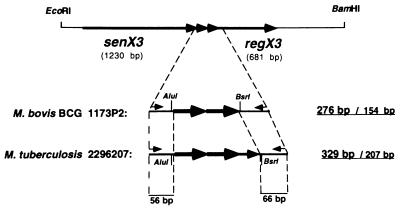

The two primers C5 and C3 chosen for the PCR amplification of the senX3-regX3 IR hybridize to the DNA sequences flanking the senX3-regX3 IR of M. tuberculosis 2296207 and M. bovis BCG 1173P2. Plasmids pRegX3Mt1 and pRegX3Bc1 containing the senX3-regX3 operons of M. tuberculosis 2296207 and BCG 1173P2, respectively, served as positive controls. As depicted in Fig. 1, with primers C5 and C3 the PCR products comprise 56 bp at the 5′ side of the senX3-regX3 IR and 66 bp at its 3′ side, in addition to the IR itself. The entire PCR product was 276 bp long when pRegX3Bc1 was used as the template and 329 bp long when pRegX3Mt1 was used as the template (Fig. 2, lanes 7 and 8, respectively).

FIG. 1.

senX3-regX3 operon and PCR amplification strategy. The 3.2-kb EcoRI-BamHI fragment containing the senX3-regX3 operon from BCG 1173P2 is shown on the top. The black arrows indicate the lengths and directions of the open reading frames, and the numbers in parentheses indicate their sizes. The PCR strategy is shown for BCG 1173P2 and M. tuberculosis 2296207. The small arrows refer to the positions of oligonucleotides C5 and C3. The first of the pair of numbers in boldface on the right refers to the total length of the amplified PCR product, whereas the second of the pair of numbers on the right refers to the size of the senX3-regX3 IR. The numbers on the bottom correspond to the sizes of the 3′ and 5′ ends of the senX3 and the regX3 genes, respectively. The senX3-regX3 IR of the two reference strains shown by the black arrows contain either two 77-bp MIRUs (larger arrows) or two 77-bp MIRUs and one 53-bp MIRU (smaller arrow). Only the AluI and BsrI restriction sites are shown.

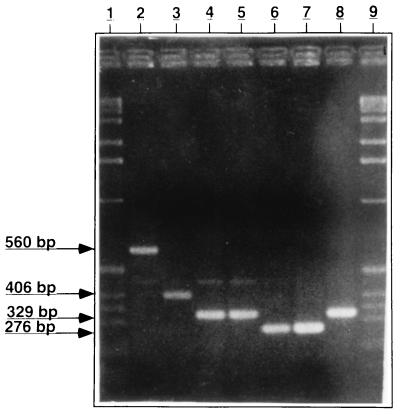

FIG. 2.

Analysis of the senX3-regX3 IR PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA was isolated from M. microti (lane 2), M. bovis AN5 (lane 3), M. tuberculosis S200 (lane 4), M. africanum (lane 5), and M. bovis BCG (Glaxo) (lane 6) and was subjected to PCR amplification with oligonucleotides C5 and C3, and the PCR fragments were analyzed by electrophoresis with a 2.5% agarose gel, followed by staining with ethidium bromide. Lanes 7 and 8, PCR fragments with pRegX3Bc1 and pRegX3Mt1 as templates, respectively. The molecular size markers are in lanes 1 and 9, and the sizes of the PCR fragments are indicated in the left margin.

When chromosomal DNA was amplified with primers C5 and C3, a single PCR product was obtained for each species of the M. tuberculosis complex: M. microti ATCC 19422, M. bovis AN5, M. tuberculosis S200, M. africanum, and the Glaxo BCG vaccine strain. However, the sizes of the amplified DNA fragments varied among the different strains, as estimated by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2) and DNA sequencing (see below). They ranged from 276 bp for the BCG strain to 329 bp for M. tuberculosis S200 and M. africanum, 406 bp for M. bovis AN5, and 560 bp for M. microti.

In addition to the performance of the PCR with the members of the M. tuberculosis complex, the same PCR was performed with 11 atypical mycobacteria, two Streptomyces strains, E. coli TG1, B. pertussis BPSM, and herring sperm DNA. No amplification product was obtained for any of these template DNAs.

Restriction and hybridization analyses of the different senX3-regX3 IR PCR products.

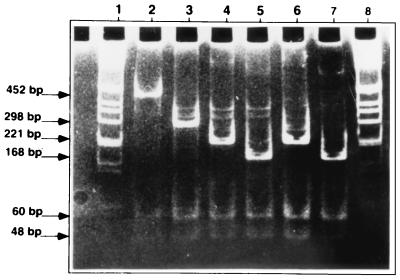

The PCR products of the different strains were digested with AluI and BsrI, two enzymes corresponding to sites located 5′ and 3′, respectively, of the senX3-regX3 IR of M. tuberculosis 2296207 and BCG 1173P2 (Fig. 1). After digestion with these enzymes, the DNA was analyzed by electrophoresis with an 8% polyacrylamide gel. As seen in Fig. 3, all PCR fragments were digested with AluI and BsrI, indicating that the restriction sites corresponding to these enzymes were present in all the fragments. In each case the expected 48- and 60-bp fragments were obtained, in addition to the fragment of variable size. The first two fragments correspond to the 5′ and the 3′ ends of the PCR fragments, respectively, whereas the fragments of variable lengths correspond to the central regions.

FIG. 3.

Restriction analysis of the senX3-regX3 IR PCR products. The senX3-regX3 IRs from M. microti (lane 2), M. bovis AN5 (lane 3), M. tuberculosis S200 (lane 4), M. bovis BCG (Glaxo) (lane 5), pRegX3Mt1 (lane 6), and pRegX3Bc1 (lane 7) were amplified by PCR, digested with AluI and BsrI, subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with an 8% polyacrylamide gel, and then stained with ethidium bromide. The molecular size markers are in lanes 1 and 8, and the sizes of the DNA fragments are indicated in the left margin.

The specificity of the senX3-regX3 IR PCR fragments was further confirmed by Southern blot analysis. All PCR products hybridized to the senX3-regX3 IR of M. tuberculosis 2296207 used as a probe (data not shown).

To test for the sensitivity of the PCR, 10-fold serial dilutions of pRegX3Mt1, ranging from 50 ng to 5 ag, were tested, and the limit for the visualization of the amplified product by ethidium bromide staining was reached with 0.5 pg of DNA, whereas the limit of detection by hybridization was about 10-fold lower. Considering that the mycobacterial genome contains roughly 4 Mbp, these detection limits correspond to approximately 100 and 10 microorganisms, respectively. In order to evaluate the sensitivity of the assay with biological specimens, fresh negative sputum was seeded with 10-fold serial dilutions of M. tuberculosis ranging from 5 × 106 to 1 × 50 CFU/ml. After extraction of DNA from 100-μl samples and PCR amplification, the samples containing from 5 × 106 to 5 × 103 CFU/ml were found to be positive. This sensitivity was in the same range as that described for the amplification of IS6110 from sputum seeded with IS6110-containing M. tuberculosis (16).

Sequence analysis of the senX3-regX3 IR PCR products.

Sequence analysis of the different PCR products obtained after amplification of the chromosomal DNA of each of the five strains indicated that all of them contained at least one copy of the 77-bp MIRU already described for M. tuberculosis 2296207 and M. bovis BCG 1173P2 (44). The M. tuberculosis, M. africanum, M. bovis, and M. microti strains contained, in addition, the 53-bp version of the MIRU. This MIRU was absent from the BCG strain. In all cases, the sequence of each individual 77- or 53-bp copy was identical to those of the 77- or 53-bp MIRUs of M. tuberculosis 2296207 and M. bovis BCG 1173P2. The size variation between the PCR products amplified from M. tuberculosis, M. africanum, M. bovis, and M. microti appeared to be due to the presence of a variable number of the 77-bp MIRU among strains. M. africanum and M. tuberculosis contained two copies of the 77-bp MIRU followed by one copy of the 53-bp MIRU, whereas M. bovis AN5 contained three copies of the 77-bp MIRU followed by a copy of the 53-bp MIRU, and M. microti contained 5 copies of the 77-bp MIRU followed by a copy of the 53-bp MIRU. The Glaxo BCG strain gave raise to a PCR fragment composed of two 77-bp MIRUs (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Distribution of mycobacterial strains within six groups according to the numbers of MIRUs present in the senX3-regX3 IR

| Mycobacterial strain(s) | PCR product lengths (bp) | senX3-regX3 IR compositiona | %b |

|---|---|---|---|

| M. microti, M. tuberculosis V.808 (IS6110−c), and M. tuberculosis V.761 (IS6110−) | 560 | 77 77 77 77 77 53 →→→→→→ | 2.5 |

| M. tuberculosis V.729 (IS6110−) | 483 | 77 77 77 77 53 →→→→→ | 0.8 |

| M. bovis AN5 and M. tuberculosis strains (n = 5) | 406 | 77 77 77 53 →→→→ | 4.9 |

| M. africanum strains (n = 2) and M. tuberculosis strains (n = 105) (including 2296207, S200, and 2 strains without mtp40) | 329 | 77 77 53 →→→ | 87.7 |

| BCG 1173P2 and BCG Glaxo | 276 | 77 77 →→ | 1.6 |

| M. tuberculosis strains (n = 3) | 252 | 77 53 →→ | 2.5 |

Numbers correspond to the 77- and 53-bp MIRUs comprising the senX3-regX3 IR.

Percentages represent the fraction of the different strains corresponding to each group.

IS6110−, the strain lacks IS6110.

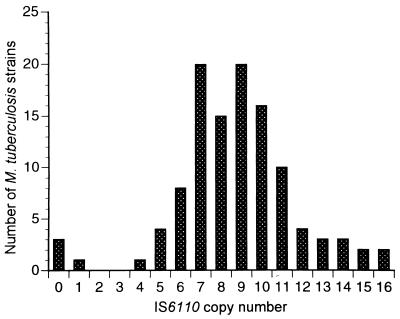

Sensitivity of the senX3-regX3 IR PCR target.

An additional M. africanum strain and 114 additional clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis were then tested for the presence of the senX3-regX3 IR. Of the 114 M. tuberculosis strains, 109 came from the Centre Hospitalier Régional of Lille, but all were from different clonal origins, as judged by their IS6110 RFLP patterns (Fig. 4). For all 109 isolates, a senX3-regX3 IR PCR product was amplified (Table 1). Of the 109 strains, 101 yielded a senX3-regX3 IR PCR product of 329 bp. The sequences of the products from 10 of these strains were checked. They contained two copies of the 77-bp MIRU and one copy of the 53-bp MIRU at the 3′ end. Eight of the 109 clinical M. tuberculosis isolates yielded either a 406-bp or a 252-bp PCR product, containing three or one 77-bp MIRU, respectively, followed by a 53-bp MIRU. The five PCR fragments of 406 bp were obtained from strains with 5, 6, 7, 7, and 10 copies of IS6110, respectively. The three 252-bp PCR fragments were obtained from strains with 7, 7, and 10 copies of IS6110, respectively. The M. africanum strain yielded a 329-bp fragment, the sequence of which was identical to that of the first M. africanum strain.

FIG. 4.

Distribution of the copy numbers of IS6110 among the M. tuberculosis strains tested. The copy numbers of IS6110 were estimated by RFLP analysis of the 109 clinical M. tuberculosis isolates that were subsequently tested by the senX3-regX3 IR PCR. Also included are the three M. tuberculosis strains which lack IS6110.

In addition to the 109 clinical isolates, 3 Vietnamese M. tuberculosis strains lacking IS6110 were analyzed by senX3-regX3 IR PCR. For one of these strains a 483-bp fragment was obtained, and for the two others a 560-bp fragment was obtained. Sequence analysis indicated that they correspond to four and five copies of the 77-bp MIRU, respectively, in each case followed by the 53-bp MIRU.

Using the PCR analysis described by Weil et al. (50), we demonstrated that all 112 clinical M. tuberculosis isolates tested possess the mtp40 gene. Therefore, two additional M. tuberculosis strains known to lack the mtp40 gene (50) were analyzed by the senX3-regX3 IR PCR. In both cases, a DNA fragment whose size and sequence were identical to those of M. tuberculosis 2296207 was amplified. Finally, the mtp40 amplification method described by Weil et al. (50) was also applied to M. microti and the M. bovis BCG vaccine strain from Glaxo. M. microti was found to possess the mtp40 gene, whereas BCG did not, as expected.

Multiplex PCR.

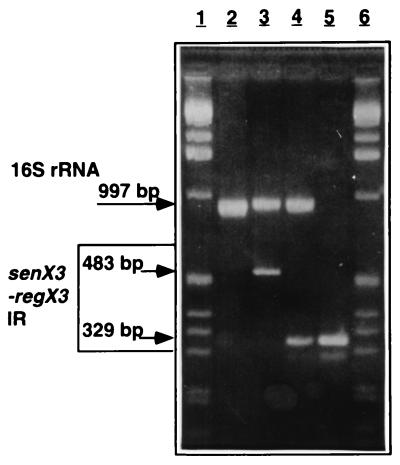

A multiplex PCR assay was developed. It was based on a one-step amplification and detection of two different genomic fragments, designed to differentiate the members of the M. tuberculosis complex and atypical mycobacteria. The primers KY18 and KY98 correspond to the 16S rRNA gene and were used to amplify DNA from all mycobacterial species, whereas the use of primers C5 and C3 permitted amplification of DNA only from the members of the M. tuberculosis complex. This multiplex amplification system yielded one fragment of 997 bp for all mycobacteria, including the 11 atypical mycobacteria used in this study, whereas no fragment was amplified when Streptomyces, B. pertussis, or E. coli DNA was used. An additional fragment corresponding to the senX3-regX3 IR and ranging in size from 252 to 560 bp was amplified only for the members of the M. tuberculosis complex. The results of a representative example of this analysis with M. avium, M. tuberculosis V.729, and M. tuberculosis S200 DNA are presented in Fig. 5.

FIG. 5.

Multiplex PCR analysis of three different mycobacterial strains. Chromosomal DNA was isolated from M. avium (lane 2), M. tuberculosis V.729 (lane 3), and M. tuberculosis S200 (lane 4) and subjected to multiplex PCR with primers C5 and C3, specific for the senX3-regX3 IR, and primers KY18 and KY98, specific for the 16S rRNA gene. The PCR products were then analyzed by electrophoresis with a 2.5% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. Lane 5, PCR product amplified with pRegX3Mt1 as the template. The molecular size markers are in lanes 1 and 6, and the sizes of the PCR fragments are indicated in the left margin.

DISCUSSION

Several promising nucleic acid-based methods have recently been developed for the rapid identification of infectious agents such as the members of the M. tuberculosis complex. Among them, PCR amplification of specific target sequences may perhaps be considered one of the most sensitive approaches to the detection of even small amounts of M. tuberculosis DNA in biological samples. In addition to the specific adaptation of the technology to a wide range of specimens, such as sputum or blood, the successful use of PCR for the detection of M. tuberculosis strongly depends on the choice of the target sequence. To ensure optimal specificity and sensitivity, the target sequence should be present in all the strains of the M. tuberculosis complex and absent from all other strains.

The most widely used target sequence so far is IS6110. This insertion element is distributed throughout the M. tuberculosis complex (47) and is, in addition, used for the typing of M. tuberculosis strains by RFLP analysis (29, 46). However, IS6110 is a member of the IS3 family, the most widely spread group of bacterial insertion sequences (30). It is therefore not too surprising that sequences homologous to IS6110 have now also been found in mycobacteria that are not part of the M. tuberculosis complex (27, 28, 31). This may perhaps account for the rates of false-positive results that were observed in several studies that used IS6110 as a target sequence and that ranged from 2.3% (18) to 20% (34). More recently, IS6110 was shown to hybridize to PCR products amplified from Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, and even from Aspergillus fumigatus (19, 20). In addition to being prone to false-positive results, targeting of IS6110 for PCR amplification may also yield false-negative results. Indeed, several M. tuberculosis strains that lack this insertion sequence have now been isolated (39, 48, 52).

As an alternative to IS6110, Herrera and Segovia (22) proposed the use of the mtp40 gene as a target for PCR amplification. This gene encodes a protein of 13,800 Da and is present in M. tuberculosis and M. africanum strains (28). It is not present in most M. bovis strains or in BCG strains (36) and was thus first proposed by Del Portillo et al. (12) as a target for PCR amplification. Several multiplex PCR assays with the mtp40 gene in conjunction with other target genes have subsequently been developed (13, 23, 28). However, a more recent study with approximately 100 M. tuberculosis isolates indicated that mtp40 is not present in all M. tuberculosis strains (50). Importantly, all the strains that did not contain the mtp40 gene were multidrug resistant, indicating that the use of mtp40 as a PCR target sequence may be less useful than initially assumed for the identification of M. tuberculosis, and especially for that of drug-resistant strains.

In this report we propose an entirely new target sequence for the detection of the members of the M. tuberculosis complex by PCR. This method is based on the presence of novel repetitive elements, named MIRUs. These elements are distributed throughout the genomes of M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, and M. leprae (44). One such MIRU is consistently found within a newly identified operon coding for a two-component system in M. tuberculosis complex strains, designated SenX3-RegX3. Both the genes coding for the two-component system and the MIRUs located between those genes show a very high degree of sequence conservation among strains of the M. tuberculosis complex. Although MIRUs and genes homologous to senX3 and regX3 are present in the M. leprae genome, their sequences are more distant from those of the M. tuberculosis complex. This has allowed us to design specific oligonucleotides that hybridize within the senX3- and regX3-coding regions and that can be used as primers to amplify the senX3-regX3 MIRUs from M. tuberculosis DNA.

By using these oligonucleotides a PCR fragment was amplified for all 116 M. tuberculosis strains analyzed, as well as for the M. bovis, M. africanum, and M. microti strains tested in this study, therefore giving 100% sensitivity within the confidence limits of this study. In contrast, no PCR fragment was amplified when DNA from other mycobacteria or other bacterial strains was used, therefore giving a specificity of 100%, also within the confidence limits of this study.

The M. tuberculosis strains tested in this study came mostly from the culture collection of the University Hospital of Lille and of the Institut Pasteur de Lille, but they were all distinct with respect to their IS6110 RFLP patterns, indicating different clonal origins. In addition to those strains, three Vietnamese strains lacking IS6110 as well as two strains lacking mtp40 were included and were also found to contain the senX3-regX3 IR.

Two-component systems often regulate functions important for the expression of virulence of pathogenic microorganisms, and their deletion then abolishes the ability of these microorganism to survive within the host (35). If the SenX3-RegX3 two-component system turns out to be involved in the virulence of mycobacteria, it is likely that all M. tuberculosis strains isolated from tuberculosis patients will contain the senX3-regX3 genes and that false-negative results will not occur on the basis of this target sequence.

Interestingly, we found some polymorphism in the sizes of the PCR fragments among the different strains. This size variation was related to the variable numbers of the 77-bp MIRU and to the presence or absence of the 53-bp MIRU. At this stage it is not known whether the variable copy numbers of MIRUs have an effect on the virulence properties of the strains. On the basis of this polymorphism, the strains could be grouped into six different groups (Table 1). The vast majority of the M. tuberculosis strains, including the two strains not containing mtp40, fell within the same group, characterized by a 329-bp PCR fragment and containing two copies of the 77-bp MIRU and one copy of the 53-bp MIRU. This group also contains the two M. africanum strains tested here.

Interestingly, the two groups containing the highest number of MIRUs (four or five copies of the 77-bp MIRU and one copy of the 53-bp MIRU) included, in addition to M. microti, only M. tuberculosis strains lacking IS6110. The 8 of 116 M. tuberculosis strains giving a 406-bp or a 252-bp PCR fragment contained average copy numbers of IS6110. The M. bovis strain fell in a group that also contains five clinical M. tuberculosis isolates, whereas the two BCG strains were found in a different group. A PCR analysis based on the senX3-regX3 IR may therefore not be sufficient for distinguishing between M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, and M. africanum, the three species of the M. tuberculosis complex that are pathogenic for humans.

Nevertheless, on the basis of the observations described in this report, we propose that the senX3-regX3 IR can be used as a target sequence for PCR to differentiate the members of the M. tuberculosis complex from other mycobacteria simply by the presence or the absence of the amplified DNA fragment. Moreover, a duplex PCR was designed to amplify simultaneously a pan-mycobacterial sequence corresponding to the 16S rRNA gene together with the senX3-regX3 IR. This additional target allows the discrimination between the tuberculous and atypical mycobacteria and is useful as a positive internal PCR control. Indeed, by this multiplex PCR, a distinct 997-bp fragment was amplified from the DNA of all mycobacterial strains tested, whereas only the strains of the M. tuberculosis complex yielded an additional, second fragment of variable size corresponding to the copy numbers of MIRUs in the senX3-regX3 IR.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank G. Delcroix, B. B. Plikaytis, G. Marshall, M. Lagranderie, and J. Dusart for the gift of bacterial strains and M. Simonet for useful discussions.

The work was supported by INSERM, Institut Pasteur de Lille, Région Nord-Pas de Calais, and Ministère de la Recherche. J.M. held a fellowship from the Fondation Recherche et Partage and now holds a fellowship from Sidaction. P.S. is a researcher of CNRS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnes P F, Bloch A B, Davidson P T, Snider D E., Jr Tuberculosis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1644–1650. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106063242307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beavis K G, Lichty M B, Jungkind D J, Giger O. Evaluation of Amplicor PCR for direct detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from sputum specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2582–2586. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2582-2586.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergmann J S, Woods G L. Clinical evaluation of the Roche Amplicor PCR Mycobacterium tuberculosis test for detection of M. tuberculosis in respiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1083–1085. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1083-1085.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bloch A B, Cauthern G M, Onorato I M, Dansbury K G, Kelly G D, Driver C R, Snider D E. National survey of drug-resistant tuberculosis in the United States. JAMA. 1994;271:665–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bloom B R, Murray C J L. Tuberculosis: commentary on a reemergent killer. Science. 1992;257:1055–1064. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloom B R. Tuberculosis: pathogenesis, protection, and control. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brudney K, Dobkin J. Resurgent tuberculosis in New York City: human immunodeficiency virus, homelessness, and the decline of tuberculosis control programs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:745–749. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.4.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carpentier E, Drouillard B, Dailloux M, Moinard D, Vallee E, Dutilh B, Maugein J, Bergogne-Berezin E, Carbonnelle B. Diagnosis of tuberculosis by Amplicor M. tuberculosis test: a multicenter study. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3106–3110. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3106-3110.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chater K F, Hopwood D A, Kieser T, Thompson C J. Gene cloning in Streptomyces. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1982;96:69–95. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-68315-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarridge J E, Shawar R M, Shinnick T M, Plikaytis B B. Large-scale use of polymerase chain reaction for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a routine mycobacteriology laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2049–2056. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2049-2056.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Amato R F, Wallman A A, Hochstein L H, Colaninno P M, Scardamaglia M, Ardila E, Ghouri M, Kim K, Patel R C, Miller A. Rapid diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis by using Roche Amplicor Mycobacterium tuberculosis PCR test. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1832–1834. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1832-1834.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Del Portillo P, Murillo L A, Patarroyo M E. Amplification of a species-specific DNA fragment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its possible use in diagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2163–2168. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.10.2163-2168.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Del Portillo P, Thomas M C, Martinez E, Maranon C, Valladares B, Patarroyo M E, Lopez M C. Multiprimer PCR system for differential identification of mycobacteria in clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:324–328. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.324-328.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Meer G, Van Genus H A. Rising case fatality of bacteriologically proven pulmonary tuberculosis in The Netherlands. Tubercule. 1992;73:83–86. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(92)90060-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devallois A, Legrand E, Rastogi N. Evaluation of Amplicor MTB test as adjunct to smears and culture for direct detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the French Caribbean. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1065–1068. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1065-1068.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doucet-Populaire F, Lalande V, Carpentier E, Bourgoin A, Dailloux M, Bollet C, Vachée A, Moinard D, Texier-Maugein J, Carbonnelle B, Grosset J. A blind study of the polymerase chain reaction for the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA. Tubercule Lung Dis. 1996;77:358–362. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(96)90102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehlers S, Ignatius R, Regnath T, Hahn H. Diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis by Gen-Probe amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis direct test. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2275–2279. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2275-2279.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eisenach K D, Sifford M D, Cave M D, Bates J H, Crawford J T. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in sputum samples using a polymerase chain reaction. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:1160–1163. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillespie S H, Newport L, McHugh T. IS6110-based PCR methods for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1348–1349. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1348-1349.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gillespie S H, McHugh T D, Newport L E. Specificity of IS6110-based amplification assays for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:799–801. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.799-801.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hellyer T J, DesJardins L E, Assaf M K, Bates J H, Cave M D, Eisenach K D. Specificity of IS6110-based amplification assays for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2843–2846. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2843-2846.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herrera E A, Segovia M. Evaluation of mtp40 genomic fragment amplification for specific detection of M. tuberculosis in clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1108–1113. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1108-1113.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herrera E A, Perez O, Segovia M. Differentiation between Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis by multiplex-polymerase chain reaction. J Appl Bacteriol. 1996;80:596–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1996.tb03263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hull R A, Gill R E, Hsu P, Minshew B H, Falkow S. Construction and expression of recombinant plasmids encoding type 1 or d-mannose-resistant pili from a urinary tract infection Escherichia coli isolate. Infect Immun. 1981;33:933–938. doi: 10.1128/iai.33.3.933-938.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs W R, Jr, Barletta R G, Udani R, Chan J, Kalkut G, Sosne G, Kieser T, Sarkis G J, Hatfull G F, Bloom B R. Rapid assessment of drug susceptibilities of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by means of luciferase reporter phages. Science. 1993;260:819–822. doi: 10.1126/science.8484123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jonas V, Alden M J, Curry J I, Kamisango K, Knott C A, Lankford R, Wolfe J M, Moore D F. Detection and identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis directly from sputum sediments by amplification of rRNA. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2410–2416. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.9.2410-2416.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kent L, McHugh T D, Billington O, Dale J W, Gillespie S H. Demonstration of homology between IS6110 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and DNAs of other Mycobacterium spp. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2290–2293. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2290-2293.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liebana E, Aranaz A, Francis B, Cousins D. Assessment of genetic markers for species differentiation within the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:933–938. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.933-938.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mazurek G H, Cave M D, Eisenach K D, Wallace R J, Jr, Bates J H, Crawford J T. Chromosomal DNA fingerprint patterns produced with IS6110 as strain-specific markers for epidemiologic study of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2030–2033. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.9.2030-2033.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McAdam R A, Hermans P W M, Van Soolingen D, Zainuddin Z F, Catty D, van Embden J D A, Dale J W. Characterization of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis insertion sequence belonging to the IS3 family. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1607–1613. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McHugh T D, Newport L E, Gillespie S H. IS6110 homologs are present in multiple copies in mycobacteria other than tuberculosis-causing mycobacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1769–1771. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1769-1771.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menozzi F D, Mutombo R, Renauld G, Gantiez C, Hannah J H, Leininger E, Brennan M J, Locht C. Heparin-inhibitable lectin activity of the filamentous hemagglutinin adhesin of Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:769–778. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.3.769-778.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore D F, Curry J I. Detection and identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis directly from sputum sediments by Amplicor PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2686–2691. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2686-2691.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noordhoek G T, Kolk A H J, Bjune G, Catty D, Dale J W, Fine P E M, Godfrey-Faussett P, Cho S-N, Shinnick T, Svenson S B, Wilson S, van Embden J D A. Sensitivity and specificity of PCR for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a blind comparison study among seven laboratories. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:277–284. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.2.277-284.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parkinson J S, Kofoid E C. Communication modules in bacteria signaling proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:71–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parra C A, Londono L P, Del Portillo P, Patarroyo M E. Isolation, characterization, and molecular cloning of a specific Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen gene: identification of a species-specific sequence. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3411–3417. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.10.3411-3417.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raviglione M C, Snider D E J, Kochi A. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis—morbidity and mortality of a worldwide epidemic. JAMA. 1995;273:220–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rogall T, Wolters J, Flohr T, Bottger E C. Towards a phylogeny and definition of species at the molecular level within the genus Mycobacterium. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1990;40:323–330. doi: 10.1099/00207713-40-4-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahadevan R, Narayanan S, Paramasivan C N, Prabhakar R, Narayanan P R. Restriction fragment length polymorphism typing of clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Madras, India, by use of direct-repeat probe. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3037–3039. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.11.3037-3039.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saiki R K, Gelfand D H, Stoffel S, Scharf S J, Higuchi R, Horn G T, Mullis K B, Erlich H A. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science. 1988;239:487–491. doi: 10.1126/science.2448875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sauton B. Sur la nutrition minérale du bacille tuberculeux. C R Acad Sci. 1912;155:860. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schaffer H E, Sederoff R R. Improved estimation of DNA fragment lengths from agarose gels. Anal Biochem. 1981;115:113–122. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schirm J, Oostendorp L A B, Mulder J G. Comparison of Amplicor, in-house PCR, and conventional culture for detection of M. tuberculosis in clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3221–3224. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3221-3224.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Supply P, Magdalena J, Himpens S, Locht C. Identification of novel intergenic repetitive units in a mycobacterial two component system operon. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:991–1003. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6361999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thierry D, Brisson-Noël A, Vincent-Levy-Frebalt V, Ngyuen S, Guesdon J-L, Gicquel B. Characterization of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis insertion sequence, IS6110, and its application in diagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2668–2673. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.12.2668-2673.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Embden J D A, Cave M D, Crawford J T, Dale J W, Eisenach K D, Gicquel B, Hermans P W M, Martin C, McAdam R, Shinnick T M, Small P M. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:406–409. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.406-409.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Soolingen D, Hermans P W M, De Haas P E W, Soll D R, van Embden J D A. Occurrence and stability of insertion sequences in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: evaluation of an insertion sequence-dependent DNA polymorphism as a tool in the epidemiology of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2578–2586. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2578-2586.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Soolingen D, de Haas P E W, Hermans P W M, Groenen P M A, van Embden J D A. Comparison of various repetitive DNA elements as genetic markers for strain differentiation and epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1987–1995. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.1987-1995.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vlaspolder F, Singer P, Roggeveen C. Diagnostic value of an amplification method (Gen-Probe) compared with that of culture for diagnosis of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2699–2703. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2699-2703.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weil A, Plikaytis B B, Butler W R, Woodley C L, Shinnick T M. The mtp40 gene is not present in all strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2309–2311. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2309-2311.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wobeser W L, Krajden M, Conly J, Simpson H, Yim B, D’Costa M, Fuksa M, Hian-Cheong C, Patterson M, Phillips A, Bannatyne R, Haddad A, Brunton J L, Krajden S. Evaluation of Roche Amplicor PCR assay for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:134–139. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.1.134-139.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuen L K W, Ross B C, Jackson K M, Dwyer B. Characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains from Vietnamese patients by Southern blot hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1615–1618. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.6.1615-1618.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]