ABSTRACT

Introduction:

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are considered the primary cause of mortality in Saudi Arabia and it is one of the major health concerns in the country. Depression can complicate, halt or even exacerbate the process of managing CVDs, making it harder to optimize the patient’s condition. The main aim of this study is to assess the depression in cardiac patients.

Methods:

A cross-sectional observational study was conducted in 257 patients diagnosed with cardiovascular diseases. The study was conducted in two governmental hospitals in Tabuk, Saudi Arabia, from December 2021 to April 2022. Depression was assessed using the Arabic version of the CESD-R questionnaire.

Results:

The mean age of the participants was 44.49 ± 12.99 years. Majority of patients were in the age group of 40-49 years (n = 92, 35.8%). More than half (53.3%) of the samples were female. The prevalence of depression among cardiac patients was 53.3%.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of depression was high among cardiac patients. It is strongly advised that routine examination and management of depression in cardiac patients be included in their regimens.

KEYWORDS: Cardiac disease, CESD-R, depression

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are considered the primary cause of mortality in Saudi Arabia and it is one of the major health concerns in the country.[1] The morbidity associated with CVDs and its impact on the patient’s quality of life make them more prone to encounter depressive symptoms during the course of the disease.[2] Depression can complicate, halt, or even exacerbate the process of managing CVDs, making it harder to optimize the patient’s condition. Depression involves multiple etiologies including biological, social, and psychological causes.[3] Depression is a common mental illness, accompanied by several characteristics such as despair, long-term sadness, and feeling of disassociation from the environment surrounding the patients. It can alter how people think and feel and it affects the person’s well-being and their social behavior. It can affect individuals of any age.[4]

In this study, we discussed the prevalence of depression in CVDs and what are the various possible contributions of several risk factors for developing depressive symptoms during the course of the illness. After a cardiac event, the patient may experience a state of depression. The sudden change in their lifestyle makes them more vulnerable, thus complicating the patient’s condition. The constant thinking of death can affect adherence to the medications therefore it can exacerbate other comorbidities. The overall deterioration increases the risk of developing depression.[5] In all age groups, depression co-occurs with a medical disease and it is linked to lower physical, mental, and social functioning than depression or physical illness alone. Co-occurrence of coronary heart disease with depression predicts a doubling of the risk of cardiac events in the years following a myocardial infarction, as well as a corresponding increase in mortality.[6]

Studies have demonstrated the crucial risk factor of depression among cardiac patients, higher risk of premature death after acute cardiac events, and also higher risk for exacerbation of nonfatal cardiac cases.[7] Depression adverse health consequences such as increased morbidity, mortality, and impairment of the physical function are all associated with cardiac disease and it has a major role in the development of these consequences.[8]

Depression was assessed among cardiac patients in Jeddah and reported that 66.9% of patients had depression.[9] Even though, several studies have discussed this topic in different countries, there is a knowledge gap regarding this subject in Tabuk. Studies have been conducted in Saudi Arabia as well, but in different cities and of single-centre study. Hence, this multi-centric study was carried out to assess the prevalence of depression in cardiac patients in Tabuk. The main objective of this study is to assess depression in cardiac patients. The primary goal is to find out the prevalence of depression among cardiac patients. The secondary goal is to find the association between age, sex, and depression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and population

This cross-sectional observational study was conducted at the Cardiology department of two governmental hospitals, Tabuk, from December 2021 to April 2022.

Inclusion criteria

Cardiac disease patients of age ≥18 years of both sexes.

Exclusion criteria

Patients less than 18 years of age and those who are not willing to participate.

Ethical concern

Ethical approval was obtained from Tabuk Institutional Review Board (UT 077/022/115). All participants gave their consent to participate in this study.

Data collection

The demographic details and the disease condition were recorded in a data collection form. Their depression was assessed by a validated Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale – Revised (CESD-R) questionnaire. The Arabic version of this questionnaire was obtained from the author with a permission to use it.[10] The CESD-R is a depression Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, Revised, to assess depression among cardiac patients. It is a 20-item self-report questionnaire used to measure symptoms of depression. It is scored on a five point Likert scale. Questions 4, 8, 12, and 16 have a score of 0 for no depression or less than a day, 1 for 1 or 2 days, 2 for 3 to 4 days, 3 for 5 to 7 days, and 4 for nearly all days for 2 weeks. All other questions will have a reverse score. The total score of the CESD-R is calculated as the sum of the 20 items. Scores range from 0 to 60. A score ≥16 indicates that a person is at risk for clinical depression. This scale measures 9 different subscales, including:

Sadness (Dysphoria): (Q. 2, 4, 6), Loss of Interest (Anhedonia): (Q. 8, 10), Appetite: (Q. 1, 18), Sleep: (Q. 5, 11, 19), Thinking/concentration: (Q. 3, 20), Guilt (Worthlessness): (Q. 9, 17), Tired (Fatigue): (Q. 7, 16), Movement (Agitation): (Q. 12, 13), Suicidal Ideation: (Q. 14, 15).

Statistical analysis

SPSS version Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. database version 21 was used. Pearson’s correlation was performed to assess the correlation between age and depression. Pearson’s Chi-square test was performed to assess the association between gender and depression. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Depression was assessed in 257 cardiac patients. The prevalence of depression among cardiac patients was 53.3%. More than half (53.3%) of the sample were female. Our sample size age ranges from 20 to 85 years old, the mean age of the participants was 44.49 ± 12.99 years. Majority of patients were in the age group of 40-49 years (n = 92, 35.8%). The demographic characteristics of the participants were shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants

| Patient characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age in years | |

| 18-29 | 37 (14.4) |

| 30-39 | 35 (13.6) |

| 40-49 | 92 (35.8) |

| 50-59 | 63 (24.5) |

| 60+ | 30 (11.7) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 120 (46.7) |

| Female | 137 (53.3) |

| Education level | |

| Grade 1-7 | 11 (4.3) |

| Grade 8-11 | 87 (33.9) |

| Completed High School | 97 (37.7) |

| College | 62 (24.1) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 200 (77.8) |

| Unmarried | 57 (22.2) |

Hypertension was the most common cardiac disease found in the patients (n = 124; 48.3%), followed by arrhythmia (n = 45; 17.5%) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Cardiac disease of the patients

| Cardiac disease | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Atrial Fibrillation | 9 (3.5) |

| Arrhythmia | 45 (17.5) |

| Arteriosclerosis | 25 (9.7) |

| Coronary artery disease | 5 (1.9) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 12 (4.7) |

| Heart Failure | 21 (8.2) |

| Hypertension | 124 (48.2) |

| Hypotension | 3 (1.2) |

| Myocardial Infarction | 4 (1.6) |

| Mitral valve regurgitation | 4 (1.6) |

| Stroke | 5 (1.9) |

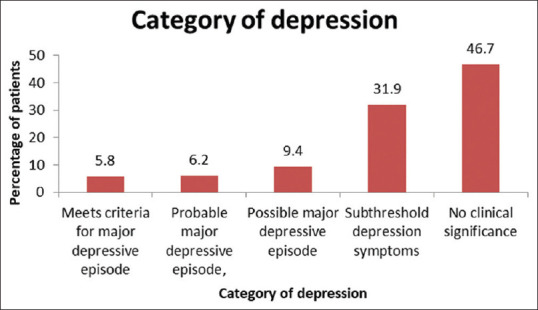

Depression was assessed using CESD-R questionnaire. The mean score of the participants was 19.32. Depression was categorized into subcategories like meets criteria for major depressive episode, probable major depressive episode, possible major depressive episode, sub-threshold depression symptoms, and no clinical significance.

Based on the scoring system, 137 patients (53.3%) showed a risk for clinical depression.

Out of 137 patients (53.3%) with risk for clinical depression, 82 (31.9%), 24 (9.3%), 16 (6.2%), and 15 (5.8%) were categorized as sub-threshold, possible, probable, and meets criteria for major depressive episodes, respectively. Remaining 120 patients (46.7%) showed no clinical significance [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Category of depression

Excluding the non-significant patients, 137 patients with depression symptoms were evaluated based on the 9 subscales. There were 62 (45.3%) male and 75 (54.7%) female. Males had more sleep disturbances and tiredness. Females had more of tiredness and movement (agitation) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Distribution of the subscales based on gender

| Subscales | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Sadness | 5 | 3 |

| Loss of interest | 4 | 10 |

| Appetite | 10 | 6 |

| Sleep | 13 | 11 |

| Thinking/Concentration | 4 | 9 |

| Guilt | 3 | 8 |

| Tired | 13 | 14 |

| Movement | 10 | 14 |

| Suicidal Ideation | 0 | 0 |

The correlation between age, sex, and the risk for developing clinical depression was assessed. Both age and sex have negative correlation with risk for depression. The correlation of age with risk of depression was clinically significant. Pearson’s Chi-square test was performed to assess the association between gender and depression. There was no association between gender and depression (p = 0.457).

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study conducted in Tabuk to assess the prevalence of depression in cardiac patients using CESD-R questionnaire. The results showed that patients with cardiac diseases were more prone to develop clinical depression. In our study, the prevalence of depression was 53.3%. It was almost consistent with other studies—51%[11] and 52.8%.[12] The results of our study were different from previous studies. Less depression rates were observed in different studies—5.9%,[13] 14%,[14,15] 15%,[16] 19.9%,[17] 21.5%,[18] 23.8%,[19] 26.4%,[20] and 37%.[21] High depression rates were observed in other studies, when compared to our study result—65%,[22] 67%,[23] and 73.2%.[24] The discrepancy in the study results might be due to difference in the characteristics of the studied sample, setting, assessment tools, design of the study, and sociocultural difference. The high prevalence rate among cardiac patients necessitates routine screening of depression among cardiac patients. Also, our findings urge the compulsion of mental health integration into cardiac patients in their treatment.

Hypertension was the most common cardiac disease found in the patients of our study. This is similar to another study.[12] In our study, depressive symptoms were observed. Males had more sleep disturbances and tiredness. Females had more of tiredness and movement (agitation). This is in accordance with another study.[25] It is common that some signs and symptoms of cardiac diseases like fatigue and tiredness are observed in depression. The identification of these depressive symptoms may help in screening and intervention for cardiac patients.

Both major depressive disorders and cardiovascular diseases are linked by biological pathways that have been discovered. Stress pathway activation has been proposed as a neurochemical mechanism linking major depressive disorder and CVDs.[26] Depression has been linked to a worsening of CVD outcomes.[27] Psychological problems, such as significant depression, stress, anxiety, insomnia, anorexia, and general discomfort, are increasingly recognized as risk factors for CVDs and vice versa, which are as important as and distinct from traditional risk factors like hypertension, diabetes, and cigarette smoking.[28] Given that depression and coronary heart disease are anticipated to be two of the top three causes of global illness burden, both disorders have significant socioeconomic implications.[29] It can help with better defining and implementing more relevant treatments if we have a better knowledge of the common causal pathways. Understanding the effect and process behind the association of depression and heart disease can allow the development of treatments on altering the harmful consequences caused by these comorbid diseases.[22]

Our study reported high rates of depression in female. This is in accordance with another study.[30] But there was no association between gender and depression in our study. This is similar to another study[18] but contrast with other study,[31] which reported that depression has a significant association with patient’s gender. Difference in study setting may be the reason for this conflicting result. The association of depressive symptoms with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality were reported.[32] Based on the findings of different studies, it is strongly advised that individuals with CVDs be evaluated for depression and treated if necessary.

Depression is the major factor affecting the quality of life of cardiac patients. Cardiologists must make sure that screening and detection of depression is undertaken for all cardiac patients.

Strengths and limitations

This multi-centric study has explored the prevalence of depression among cardiac patients in Tabuk.

The major limitation of this study is convenience sampling, which may not be useful to generalize the results. Depression was assessed based on subjective information provided by the patients, and objective evidence was not assessed.

CONCLUSION

In Tabuk, Saudi Arabia, this study looked at the prevalence of depression in patients with cardiac disease. The findings of this study back up previous findings that people with cardiac diseases are at a higher risk of developing clinical depression. Furthermore, cardiac diseases were found to be predictive of developing depression. It is strongly advised that routine examination and management of depression in cardiac patients be included in their regimens.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Fatima Eid Albalawi, Head nurse, ECHO room in King Khalid Hospital for her great support and help.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aljefree N, Ahmed F. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease and associated risk factors among adult population in the Gulf region:A systematic review. Adv Public Health. 2015:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elderon L, Whooley MA. Depression and cardiovascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;55:511–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albuhayri AH, Alshaman AR, Alanazi MN, Aljuaid RM, Albalawi RI, Albalawi SS, et al. A cross-sectional study on assessing depression among hemodialysis patients. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2022;13:266–70. doi: 10.4103/japtr.japtr_322_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jha MK, Qamar A, Vaduganathan M, Charney DS, Murrough JW. Screening and management of depression in patients with cardiovascular disease:JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:1827–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burcusa SL, Iacono WG. Risk for recurrence in depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:959–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khawaja IS, Westermeyer JJ, Gajwani P, Feinstein RE. Depression and coronary artery disease:The association, mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2009;6:38–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ceccarini M, Manzoni GM, Castelnuovo G. Assessing depression in cardiac patients:What measures should be considered? Depress Res Treat. 2014;2014:148256. doi: 10.1155/2014/148256. doi:10.1155/2014/148256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Honig A, Deeg DJ, Schoevers RA, Eijk van JT, et al. Depression and cardiac mortality:Results from a community-based longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:221–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.AlRahimi J, Alattas R, Almansouri H, Alharazi GB, Mufti HN. Assessment of different risk factors among adult cardiac patients at a single cardiac center in Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2020;12:e11649. doi: 10.7759/cureus.11649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rababah J, Al-Hammouri MM, Drew BL, Ta'an W, Alawawdeh A, Dawood Z, et al. Validation of the Arabic version of the center for epidemiologic studies depression-revised:A comparison of the CESD-R and CESDR-12. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:450–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freedland KE, Rich MW, Skala JA, Carney RM, Dávila-Román VG, Jaffe AS. Prevalence of depression in hospitalized patients with congestive heart failure. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:119–28. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000038938.67401.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umer H, Negash A, Birkie M, Belete A. Determinates of depressive disorder among adult patients with cardiovascular disease at outpatient cardiac clinic Jimma University Teaching Hospital, South West Ethiopia:Cross-sectional study. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2019;13:13. doi: 10.1186/s13033-019-0269-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothenbacher D, Hahmann H, Wüsten B, Koenig W, Brenner H. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with stable coronary heart disease:Prognostic value and consideration of pathogenetic links. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14:547–54. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3280142a02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akhtar MS, Malik SB, Ahmed MM. Symptoms of depression and anxiety in post-myocardial infarction patients. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2004;14:615–8. doi: 10.2004/JCPSP.615618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanssen TA, Nordrehaug JE, Eide GE, Bjelland I, Rokne B. Anxiety and depression after acute myocardial infarction:An 18-month follow-up study with repeated measures and comparison with a reference population. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009;16:651–9. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32832e4206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moraska AR, Chamberlain AM, Shah ND, Vickers KS, Rummans TA, Dunlay SM, et al. Depression, healthcare utilization, and death in heart failure:A community study. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:387–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin JS, Neita SM, Gibson RC. Depression among cardiovascular disease patients on a consultation-liaison service at a general hospital in Jamaica. West Indian Med J. 2012;61:499–503. doi: 10.7727/wimj.2012.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutledge T, Reis VA, Linke SE, Greenberg BH, Mills PJ. Depression in heart failure a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1527–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhital PS, Sharma K, Poudel P, Dhital PR. Anxiety and depression among patients with coronary artery disease attending at a cardiac center, Kathmandu, Nepal. Nurs Res Pract. 2018;2018:4181952. doi: 10.1155/2018/4181952. doi:10.1155/2018/4181952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meneghetti CC, Guidolin BL, Zimmermann PR, Sfoggia A. Screening for symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients admitted to a university hospital with acute coronary syndrome. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2017;39:12–8. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2016-0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bokhari SS, Samad AH, Hanif S, Hadique S, Cheema MQ, Fazal MA, et al. Prevalence of depression in patients with coronary artery disease in a tertiary care hospital in Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2002;52:436–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.AbuRuz ME. Anxiety and depression predicted quality of life among patients with heart failure. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2018;11:367–3. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S170327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pena FM, Silva Soares da J, Paiva BT, Piraciaba MC, Marins RM, Barcellos AF, et al. Sociodemographic factors and depressive symptoms in hospitalized patients with heart failure. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2010;15:e29–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goudarzian AH, Nia HS, Tavakoli H, Soleimani MA, Yaghoobzadeh A, Tabari F, et al. Prevalence of cardiac depression and its related factors among patients with acute coronary syndrome. Asian J Pharm Res Health Care. 2016;8:30–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khalil AI, Muneer MF. Assessment of anxiety and depression among heart failure patients at king faisal cardiac center, King Khalid Hospital, Jeddah. J Nurs Care. 2019;8:481. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dhar AK, Barton DA. Depression and the link with cardiovascular disease. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:33. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00033. doi:10.3389/fpsyt. 2016 00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hare DL, Toukhsati SR, Johansson P, Jaarsma T. Depression and cardiovascular disease:A clinical review. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1365–72. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sher Y, Lolak S, Maldonado JR. The impact of depression in heart disease. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12:255–64. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fotopoulos A, Petrikis P, Sioka C. Depression and coronary artery disease. Psychiatr Danub. 2021;33:73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allabadi H, Alkaiyat A, Alkhayyat A, Hammoudi A, Odeh H, Shtayeh J, et al. Depression and anxiety symptoms in cardiac patients:A cross-sectional hospital-based study in a Palestinian population. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:232. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6561-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carvalho IG, Bertolli ED, Paiva L, Rossi LA, Dantas RA, Pompeo DA. Anxiety, depression, resilience and self-esteem in individuals with cardiovascular diseases. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2016;24:e2836. doi: 10.1590/1518-8345.1405.2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katon WJ. Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13:7–23. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.1/wkaton. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]