ABSTRACT

Introduction:

Tobacco has been linked multiple times to many health implications. The relationship between periodontitis and tobacco was thoroughly investigated in this systemic review to evaluate if tobacco specifically smoking impacts the progression of periodontal through impairing vascular and immunity mediators processes.

Materials and Methods:

The manual and electronic literature searches up to 2020 in the databanks of the EMBASE, MEDLINE, PUBMED, and SCOPUS were conducted. The search terms were “periodontitis,” “periodontitis diseases,” “smoking,” “tobacco use,” “tobacco,” and “cigarette, pipe, and cigar.” The types of studies included were restricted to the original studies and human trials. Analyses of subgroups and meta-regression were used to calculate the heterogeneity.

Results:

15 papers total were considered in the review, however only 14 of them provided information that could be used in the meta-analysis. Smoking raises the incidence of periodontitis by 85% according to pooled adjusted risk ratios (risk ratio 1.845, CI (95%) =1.5, 2.2). The results of a meta-regression analysis showed that age, follow-up intervals, periodontal disease, the severity of periodontitis, criteria used to determine periodontal status, and loss to follow-up accounted for 54.2%, 10.7%, 13.5%, and 2.1% of the variation in study results.

Conclusion:

Smoking has an undesirable impact on periodontal incidence and development. Therefore, when taking the history of the patients at the initial visits the information about the habit of smoking has to be thoroughly noted.

KEYWORDS: Frequency, oral diseases, periodontitis, smoking

INTRODUCTION

The consumption of tobacco in the form of smoking is recognized as a substantial risk factor for chronic non-communicable ailments. The majority of deaths worldwide are now caused by diseases associated with smoking.[1,2] In spite of a decline in tobacco usage, estimations indicate that 10% of all fatalities in 2020 will be attributable to smoking.[1] The overall tax revenue from tobacco products is exceeded by health costs associated with cigarette-related ailments.[1] As a result, both individuals and healthcare systems are significantly burdened by the size of tobacco-related expenditures.

The global burden of chronic diseases includes periodontitis since it is a chronic, inflammatory, destructive disorder that affects the tooth’s supporting components.[3] Periodontitis eventually results in the loss of a tooth. Oral diseases have an effect on mastication, quality of life, speech, and consequently self-esteem.[4] Dental caries is on the decline, although the severity of periodontitis has not changed since 1990.[3] There are about 700 million cases of severe periodontitis worldwide, according to a meta-analysis of the condition’s prevalence.[3] The prevalence of periodontitis is anticipated to rise as a result of longer life expectancies and a marked decline in loss of the tooth caused by caries. We take it for granted that cigarette use and periodontitis are related.

Nevertheless, the preponderance of the data comes from studies that are designed as cross-sectional, which makes it impossible to establish temporal connections. Furthermore, numerous epidemiologic studies on the subject have significant methodological flaws, such as high participant loss and short-term follow-up, which cause estimates from different research to differ. The few published evaluations on the subject to date have concentrated on the impact of quitting smoking on periodontal healing; there hasn’t been a systematic review done on the subject.[5,6] Furthermore, estimates of the size of the relationship between smoking and the development of periodontal conditions while correcting for discrepancies between studies have never been made.

The studies that are designed as prospective longitudinal and cross-sectional are evaluated to analyze the impact smoking has on periodontium and the implications on periodontal diseases. The design method differences between the studies were analyzed by using the meta-regression methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The questionnaire was prepared on the basis of the PRISMA standards and protocol guidelines and served as the foundation for this systematic review’s report.[7] The evaluation inquiry is: Is smoking tobacco linked to the development or occurrence of periodontitis?

Eligibility requirements

Types of research: The original studies that are designed to be prospective longitudinal which examined the link between tobacco use and periodontal inflammation as well as other periodontal diseases and had a follow-up of around 12 months were taken into consideration.

Trials examining the impact on the healing after periodontal surgeries in smokers and studies involving patients receiving supportive periodontal therapy were excluded from consideration. Finally, research that included comments or conference abstracts was not included, including case reports, ethnographic studies, retrospective longitudinal, cross-sectional, case-control, literature reviews, and case studies.

Measurements of exposure and results: To meet the requirements for inclusion, studies must exhibit at least 2 indicators of periodontitis “clinical attachment level”, “probing depth”, and “alveolar bone loss”. The research’s specified monitoring parameters for periodontal health were acceptable.

Search Techniques: The manual and electronic literature searches up to 2020 in the databanks of the EMBASE, MEDLINE, PUBMED, and SCOPUS were conducted. The search terms were: “Periodontitis [MeSH] OR Periodontitis [MeSH] OR Chronic Periodontitis [MeSH] OR Periodontal diseases [all] OR Periodontitis [all] OR Chronic Periodontitis [all]) AND (Smoking [MeSH] OR Tobacco Use [MeSH] OR Tobacco [MeSH] OR Tobacco Products [MeSH] OR Smoking [all] OR Tobacco Use [all] OR (Cohort Studies [MeSH] OR Longitudinal Studies[MeSH] OR Follow-up Studies[MeSH] OR Prospective Studies[MeSH])”. No language or date limitations were imposed. All of the included papers’ reference lists were searched.

Selection of Studies: All phases of the review involved managing the references using the program Endnote, version X8.0.1. First, repeated references were disregarded. Then, based on the qualifying requirements, two reviewers independently assessed the titles and abstracts. Conflicts were resolved by consensus when lists were compared. Established on the aforementioned selection criteria, the identical two reviewers evaluated the entire texts of articles that might be included in the review. Comparing the lists allowed for disagreements to be resolved through dialogue. During the review process, the statistic was utilized to gauge the degree of arrangement among the reviewers.

Extraction of Data: The following categories were used to organize the information taken from the studies:

the publication’s attributes, such as the author and the publication year;

study features, including the size of the sample, key findings, study location, and follow-up time; and

The features of the exposure and the result: the definition and standards by which periodontitis and smoking are assessed, as well as the standards by which the periodontal state has changed. Additionally, data on the analytical methodology, the raw and adjusted outcomes, and confounders were gathered.

Extracted data were associated, and conversations were made to come to an agreement in the event of a dispute. This strategy was selected to prevent the inclusion of people from the reference category more than once. Only the most recent estimate was acquired in research that included numerous assessments over time.

Critical Evaluation: The quality of the papers comprised in this review was evaluated with a specific “Newcastle-Ottawa scale for cohort studies”. The scale consists of eight questions distributed across three dimensions: (1) research group selection, (2) study group comparability, and (3) result evaluation and adequate follow-up. Both reviewers met in advance of the critical evaluation procedure to discuss how each parameter should be assessed. Independently evaluating the papers critically, the reviewers came to an agreement via discussion when there were any differences. As an alternative to presenting an overall score to indicate the level of the study‘s quality, a critical assessment according to each dimension of the instrument was visually displayed. Stata, version 14.2, was used to conduct all analyses. Fixed and random effect models were used to calculate the combined risk ratio estimate. The random effect model was favored when there was heterogeneity (I2450% or Chi-square P value 0.05). When facts and projections were presented as an OR estimates of the relative risk were made accessible.[8,9] Of the lack of information, the authors were contacted for more details. The estimations were combined using two analytical models: one for unadjusted outcomes and the other for corrected results. Both models would incorporate a study‘s inclusion of both estimations. The only processed model for additional analysis was the pooled model of adjusted findings.

Analysis of Heterogeneity’s Sources: random effects model was sued for the meta-regression.[10,11]

Risk Fraction attributable to the Population: the degree to which smoking cessation will lower periodontal inflammation was calculated using the approach suggested by Miettinen.[12-14] This approach takes into account potential confounding, hence using it is advised for results that have been corrected.

RESULTS

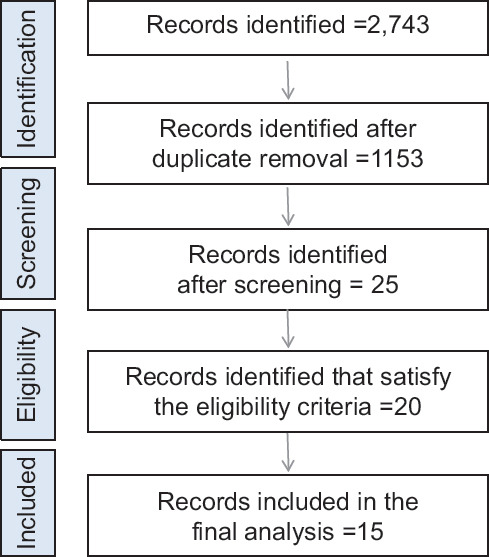

2,743 results from electronic searches. 1,153 of those were duplicates, which were then removed. As a result, 1,590 papers’ titles and abstracts were scrutinized for eligibility. Finalized studies were 15. Only 14 papers, nevertheless, provided information that could be used in a meta-analysis Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart exhibiting the study selection

Using the statistics, the reviewers’ agreement on the study’s eligibility was 0.92. The inability to ascertain the prospective design of some research gave rise to disagreements. Additionally, there was unanimity in the choice of studies for the meta-analysis. In the critical evaluation, a score of 0.94 was attained. When there was disagreement, a solution was worked out through conversation.

The primary attributes of the studies are described in Table 1. There were just two studies undertaken in low- to middle-income nations: 21 and 27. The follow-up period ranged from 1 to 38 years, with follow-up >5 years being presented in four investigations.[17,24,26,29] Most definitions of smoking status used the terms smoker and non-smoker. Three research employed radiographic bone loss to track periodontal damage, whereas 11 studies-clinical inspections. Each study had a different way of measuring the incidence or progression of periodontal disease. The only studies that omitted adjusted estimates were two.[26,27]

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Author, year | Sample characteristics | Criteria for smoking status | Assessment of periodontitis | Follow-up period | Criteria for periodontitis diagnosis | Incidence of periodontitis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomson et al., 2013[29] | 831 individuals enrolled in the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study | Non-smokers Smokers | Clinical examination: full mouth examination, 3 sites per tooth (age 38 years) | 38 years | Clinical attachment level | ≥3 mm of clinical attachment loss shown in trajectory groups of disease progression as follows: Low, Moderately increasing, and Markedly increasing |

| Thomson et al., 2004[28] | 342 individuals aged 60 years or more enrolled in the South Australian Dental Longitudinal Study | Non-smokers Ever smokers Smokers | Clinical examination: full mouth examination, 3 sites per tooth | 5 years | Clinical attachment level | 42 sites of ≥3 mm of attachment loss |

| Suda et al., 2000[27] | 310 individuals aged 15–44 years | Non-smokers Smokers (1, 2– 4; 5–14; ≥15 packs/year) | Clinical examination: full mouth examination, 6 sites per tooth | 2 years | Clinical attachment level | ≥1 site of ≥3 mm of clinical attachment loss |

| Paulander et al., 2004[26] | 295 individuals (164 women and 131 men) aged 50 years at baseline | Never smokers Current smokers | Full-mouth radiographic assessment | 10 years | Alveolar bone loss | Alveolar bone loss 40.5 mm |

| Okamoto et al., 2006[16] | 1,332 men aged 30–59 years | Never smokers Current smokers (1–19, 20, ≥21 cigarettes per day) | Clinical examination: partial mouth examination (10 teeth of all sextants) | 4 years | Community Periodontal Index: scores 3 and 4 (individual level) | Community Periodontal Index score 3 or 4 in at least 1 sextant |

| Ogawa et al., 2002[25] | 394 individuals (186 women and 208 men) aged 70 years and older | Non-smokers Smokers | Clinical examination: full mouth examination, 6 sites per tooth | 2 years | Clinical attachment level | 41 site of ≥3 mm of clinical attachment loss |

| Norderyd et al., 1999[24] | 361 individuals aged 20–60 years | Non-smokers Smokers | Full-mouth radiographic assessment | 15–17 years | Alveolar bone loss | Proximal alveolar bone loss 420% at ≥6 sites |

| Morita et al., 2011[15] | 3,590 individuals (803 women and 2,787 men) aged 21–69 years | Never smokers Current smokers | Clinical examination: partial mouth examination (10 teeth of all sextants) | 5 years | Probing depth (worst site per tooth was recorded) | Probing depth ≥4 mm in at least 1 sextant |

| Mdala et al., 2014[23] | 162 individuals aged 26–84 years | Non-smokers Smokers | Clinical examination: full mouth examination, 1 site per tooth | 2 years | Probing depth and clinical attachment level | Probing depth or clinical attachment loss 44 mm |

| Kibayashi et al., 2007[22] | 219 individuals aged 18–63 years (193 men and 26 women) | Never/former smokers Current smokers Packs/year | Clinical examination: full mouth examination, 6 sites per tooth | 4 years | Probing depth (worst site per tooth was recorded) | Three or more teeth with probing depth of ≥2 mm |

| Haas et al., 2014[21] | 653 individuals aged 14 and older enrolled in the Epidemiology of Periodontal Diseases: The Porto Alegre Study | 10 packs/year ≥10 packs/year | Clinical examination: full mouth examination, 6 sites per tooth | 5 years | Clinical attachment level | Clinical attachment loss progression ≥3 mm in ≥2 teeth Clinical attachment loss progression ≥3 mm in ≥4 teeth |

| Gilbert et al., 2005[19] | 560 individuals enrolled in the Florida Dental Care Study | Never/former smokers Current smokers | Clinical examination: full mouth examination, 6 sites per tooth | 4 years | Clinical attachment level (worst site per tooth was recorded) | One or more teeth of ≥3 mm of clinical attachment loss |

| Gätke et al., 2012[20] | 2,558 individuals aged 20–81 years enrolled in the Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP) | Never smokers Current smokers | Clinical examination: half mouth examination, 4 sites per tooth | 5 years | Clinical attachment level | Two or more sites of ≥3 mm of clinical attachment loss |

| Beck et al., 1997[18] | 540 individuals from The Piedmont 65+Study of the Elderly | Never/former smokers Current smokers | Clinical examination: full mouth examination, 2 sites per tooth | 5 years | Clinical attachment level | Clinical attachment loss ≥3 mm for each interval of follow-up |

| Baljoon et al., 2005[17] | 91 individuals from a periodontal health study carried out in musicians in Stockholm | Never smokers Current smokers | Full-mouth radiographic assessment | 10 years | Interdental marginal bone of at least 2 mm | ≥2 difference in the number of vertical defects after baseline |

A meta-analysis contained ten rough estimates (Risk ratio = 1.79, 95% CI = 1.4, 2.3). Smoking increased the risk of periodontitis by 85%, (Risk ratio = 1.85, 95% CI = 1.5, 2.2; Table 2), with significant heterogeneity in the collective estimates (P < 0.001). In a meta-regression examination, 15 assessments from 12 papers with adjusted findings were included. Loss to follow-up 10.7%, periodontal state assessment criteria and severity aspect of periodontitis progression 2.1%, time of follow-up 13.5%, age 54.2%, incidence 16.9%, and meta-regression analysis explained the variation between studies [Table 2]. Studies with loss to follow-up <30%, with follow-up times of 5 years, and studies using radiographic alveolar bone loss, showed greater correlations.

Table 2.

Meta-regression and subgroup analysis according to methodological covariates

| Variable | Number of estimates | Risk ratio (95% CI) | P in bivariable analysis | Bivariable adjusted R2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 0.71 | - | ||

| <500 | 5 | 2.0 (1.4, 2.8) | ||

| ≥500 | 10 | 1.7 (1.4, 2.1) | ||

| Type of sample | 0.91 | - | ||

| Convenience | 2 | 2.0 (1.4, 2.9) | ||

| Population-based | 13 | 1.8 (1.5, 2.2) | ||

| Age of the participants | 0.01 | 54.2% | ||

| Adults only | 7 | 3.0 (2.0, 4.3) | ||

| Adults and elders | 8 | 1.3 (1.2, 1.4) | ||

| Sex | 0.87 | |||

| Predominance of males | 7 | 2.0 (1.5, 2.8) | ||

| Predominance of females | 2 | 1.8 (1.1, 3.0) | ||

| Balanced | 6 | 1.6 (1.3, 2.1) | ||

| Follow-up period | 0.20 | 13.5% | ||

| 5 years | 11 | 1.6 (1.4, 2.0) | ||

| ≥5 years | 4 | 2.8 (1.5, 5.0) | ||

| Loss to follow-up | 0.19 | 10.7% | ||

| 430% | 7 | 1.4 (1.2, 1.7) | ||

| r30% | 8 | 2.3 (1.6, 3.2) | ||

| Smoking status assessment | ||||

| Dichotomous (yes or no) | 10 | 1.7 (1.4, 2.2) | ||

| Quantity | 5 | 2.1 (1.3, 3.7) | 0.67 | - |

| Periodontal examination | 0.47 | - | ||

| Full or partial mouth | 7 | 1.6 (1.3, 2.0) | ||

| Index teeth | 6 | 1.8 (1.3, 2.5) | ||

| Radiographic assessment | 2 | 2.9 (1.3, 6.4) | ||

| Periodontal measure used | 0.18 | 2.1% | ||

| Clinical attachment level | 7 | 1.5 (1.3, 1.8) | ||

| Probing depth | 6 | 2.0 (1.4, 3.0) | ||

| Alveolar bone loss | 2 | 2.9 (1.3, 6.4) | ||

| Incidence or progression of Periodontitis-extent | 0.91 | - | ||

| 1 site | 8 | 1.9 (1.4, 2.4) | ||

| ≥2 sites | 6 | 1.8 (1.4, 2.5) | ||

| Periodontitis progression-severity | ||||

| 1–2 mm | 6 | 2.6 (1.8, 3.6) | 0.10 | 16.9% |

| ≥3 mm | 8 | 1.4 (1.2, 1.7) | ||

| Disease occurrence measure | 0.61 | - | ||

| Incidence | 8 | 2.1 (1.5, 3.0) | ||

| Progression | 6 | 1.7 (1.3, 2.1) | ||

| Multivariable adjusted R2 of the model (%) | 93.6% |

DISCUSSION

These results show a strong positive relationship between cigarette use and increased periodontitis risk in prospective longitudinal studies. Furthermore, according to calculations made using “Population Attributable Risk Fraction”, quitting smoking would reduce this population’s risk of periodontal disease by about 14%. Although some probable processes have been proposed, it is still unclear how smoking tobacco influences the occurrence and development of periodontitis. They include how smoking affects the immune system, the microbiota, and the ability of the periodontium to repair. It is suggested that a change in the subgingival biofilm’s make-up brought about by smoking may cause along with a rise in the frequency of periodontal infections. Neutrophils that help in healing also are lowered in migration due to smoking. The neutrophils are also known to be more destructive in smokers than non-smokers.[30-34]

For instance, increased levels of various bone-resorbing chemical agents like cytokines and the factors like interleukins and alpha-2-macroglobulin are elevated in smokers.[35-39] These may directly act on the cells that relate to the bone depositions or may cause soft tissue destruction. Periodontal healing could be hampered by the increased collagenolytic activity.[40-42]

The link between cigarette use and periodontitis was modified by follow-up time, according to the findings of the meta-regression study. A probable aggregate effect of smoking on the periodontium was indicated by follow-up time, which accounted for roughly 15% of the variation between trials.[29] The incidence and development of periodontitis should also take chronicity into account. This cumulative effect has been demonstrated in the Dunedin birth cohort by Thomson and colleagues.[43] In comparison to non-smokers, people who had smoked the most throughout their lives had worse periodontal health (a higher incidence and faster advancement of periodontitis).[43] Comparable results were found in a Brazilian birth cohort study, which showed that smoking amplified the risk of periodontitis by age 31.[44] The high dropout rate, which was established as above 30% in this review, was another factor that affected the variation in study quality.[45] In prospective longitudinal investigations, loss to follow-up is unavoidable and can result in selection bias.[46]

Additionally, each study’s participant age had a significant impact on the estimations, with the presence of elders resulting in a decrease in the estimates. When predicting the outcome of periodontitis, tooth loss in older participants is a crucial factor since it may be a source of bias and cause the risk for periodontitis to be underestimated.[47] The proportion of participants without teeth and the number of teeth present should therefore be reported according to age groups, according to the guidelines for reporting epidemiologic research.[48]

The periodontal assessment criteria had an impact on the pooled estimate as well. Studies that used the radiographic bone loss to assess periodontitis found a stronger correlation. According to studies, clinical attachment loss may be overestimated by radiographic evidence of bone loss.[49] The periodontal evaluation criteria should be of caution in longitudinal research since the short-term follow-up makes the disparity between the two measures more pronounced.[49]

Variability between studies was also linked to the severity of periodontitis occurrence and progression. A subgroup analysis showed that papers using a cutoff of 1-2 mm to assess illness incidence or progression had higher estimates than studies using a cutoff of more than 3 mm. A greater number of sites will be impacted by the disease if the cutpoint used to gauge disease progression is lowered, which may raise the risk.[50] Which value should be used to track the occurrence and progression of periodontitis is a matter of debate. Upcoming studies should employ at least a 3-mm threshold to observe periodontal changes over time and longer follow-up. This is because there is a chance that a calibration errors of 1 to 2 mm will occur while taking clinical measurements, and this may necessitate larger sample sizes.[51]

It is important to highlight some of this review’s advantages

Only the evaluation of longitudinal prospective studies offered solid proof of the link between smoking and periodontitis. Furthermore, a total of 11,000 people were included in the 15 studies. The results were further strengthened by the sensitivity analysis, as the absence of any estimate did not cancel out the observed link. It is important to emphasize the outcome of the population-attributable percentage since it offers an assessment of the impact of smoking on the risk of periodontitis. The use of meta-regression provided insight into the relationship between smoking and periodontitis from many angles. Therefore, health professionals and decision-makers can also utilize these findings in addition to researchers.

There are various limits in the study that should be taken into account. Despite doing a thorough search across many databanks, it is impossible to be certain that all research addressing the link between cigarette use and periodontitis was taken into account. One can speculate that the review’s weakness stems from its pooled analysis of studies with pertinent differences among them. Meta-estimates from observational research are frequently extremely diverse. Additionally, the choice to combine all of the research into a single analysis was made in order to investigate potential sources of variation amid them. Because there weren’t many types researches with negative outcomes in this analysis, the small-study effect may have exaggerated the pooled estimate.

Another thing that needed to be thoroughly looked at was that it was impossible to guarantee that the outcome would not be there at the start of the investigation. However, the authors made an effort to downplay the problem by outlining the disease’s existing prevalence in the community as well as any changes in incidence or progression. Another significant flaw was the use of self-reported data in determining the exposure.

CONCLUSION

Collectively, these findings lend credence to the link between smoking and the onset and advancement of periodontitis. However, there are a number of strategies to improve this information. The focus of the next prospective longitudinal research should be on assessing the potential dose-dependent effect of cigarette smoking on periodontitis. Government encouragement is suggested for the research since smoking is still a known health issue.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014. Geneva: UN General Assembly; 2014. [[Last accessed on 2017 Jul 17]]. http://apps.who.int/iris/bit stream/10665/148114/1/9789241564854_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010:A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2224–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray CJL, Marcenes W. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990–2010:A systematic review and meta-regression. J Dent Res. 2014;93:1045–53. doi: 10.1177/0022034514552491. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034514552491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan DS, Spencer AJ, Roberts-Thomson KF. Quality of life and disability weights associated with periodontal disease. J Dent Res. 2007;86:713–7. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600805. https://doi.org/10.1177/15440591070↘805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiorini T, Musskopf ML, Oppermann RV, Susin C. Is there a positive effect of smoking cessation on periodontal health?A systematic review. J Periodontol. 2014;85:83–91. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.130047. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop0.2013.130047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chambrone L, Preshaw PM, Rosa EF, Heasman PA, Romito GA, Pannuti CM, et al. Effects of smoking cessation on the outcomes of non-surgical periodontal therapy:A systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40:607–15. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12106. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG The PRISMA group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses:The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pmed. 1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk?A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280:1690–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:923–36. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson SG, Higgins JPT. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med. 2002;21:1559–73. doi: 10.1002/sim.1187. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egger M, Smith GD. Bias in location and selection of studies. BMJ. 1998;316:61–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7124.61. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.316.7124.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miettinen OS. Proportion of disease caused or prevented by a given exposure, trait or intervention. Am J Epidemiol. 1974;99:325–32. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121617. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daly LE. Confidence limits made easy:interval estimation using a substitution method. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:783–90. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009523. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva MF, Leite FRM, Ferreira LB, Pola NM, Scannapieco FA, Demarco FF, et al. Estimated prevalence of halitosis:A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22:47–55. doi: 10.1007/s00784-017-2164-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-017-2164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morita I, Okamoto Y, Yoshii S, Nakagaki H, Mizuno K, Sheiham A, et al. Five-year incidence of periodontal disease is related to body mass index. J Dent Res. 2011;90:199–202. doi: 10.1177/0022034510382548. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034510382548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okamoto Y, Tsuboi S, Suzuki S, Nakagaki H, Ogura Y, Maeda K, et al. Effects of smoking and drinking habits on the incidence of periodontal disease and tooth loss among Japanese males:A 4-yr longitudinal study. J Periodontal Res. 2006;41:560–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2006.00907.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0765.2006.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baljoon M, Natto S, Bergström J. Long-term effect of smoking on vertical periodontal bone loss. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:789–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00765.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck JD, Cusmano L, Green-Helms W, Koch GG, Offenbacher S. A 5-year study of attachment loss in community-dwelling older adults:Incidence density. J Periodontal Res. 1997;32:506–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1997.tb00566.x. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1600-0765.1997.tb00566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilbert GH, Shelton BJ, Fisher MA. Forty-eight-month periodontal attachment loss incidence in a population-based cohort study:Role of baseline status, incident tooth loss, and specific behavioral factors. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1161–70. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.7.1161. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2005.76.7.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gätke D, Holtfreter B, Biffar R, Kocher T. Five-year change of periodontal diseases in the study of health in pomerania (SHIP) J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:357–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01849.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 1600- 051X.2011.01849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haas AN, Wagner MC, Oppermann RV, Rosing CK, Albandar JM, Susin C. Risk factors for the progression of periodontal attachment loss:A 5-year population-based study in South Brazil. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:215–23. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12213. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kibayashi M, Tanaka M, Nishida N, Kuboniwa M, Kataoka K, Nagata H, et al. Longitudinal study of the association between smoking as a periodontitis risk and salivary biomarkers related to periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2007;78:859–67. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060292. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop. 2007.060292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mdala I, Olsen I, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS, Thoresen M, de Blasio BF. Comparing clinical attachment level and pocket depth for predicting periodontal disease progression in healthy sites of patients with chronic periodontitis using multi-state Markov models. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:837–45. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12278. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norderyd O, Hugoson A, Grusovin G. Risk of severe periodontal disease in a swedish adult population. A longitudinal study. J Clin Periodontol. 1999;26:608–15. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.1999.260908.x. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-051X. 1999.260908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogawa H, Yoshihara A, Hirotomi T, Ando Y, Miyazaki H. Risk factors for periodontal disease progression among elderly people. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:592–97. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290702.x. https://doi.org/10.1034/j. 1600-051X. 2002.290702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paulander J, Wennstrom JL, Axelsson P, Lindhe J. Some risk factors for periodontal bone loss in 50-year-old individuals. A 10-year cohort study. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:489–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00514.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suda R, Cao C, Hasegawa K, Yang S, Sasa R, Suzuki M. 2-year observation of attachment loss in a rural Chinese population. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1067–72. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.7.1067. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2000.71.7.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomson WM, Slade GD, Beck JD, Elter JR, Spencer AJ, Chalmers JM. Incidence of periodontal attachment loss over 5 years among older South Australians. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:119–25. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6979.2004.00460.x. https://doi. org/10.1111/j. 0303-6979.2004.00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomson WM, Shearer DM, Broadbent JM, Foster Page LA, Poulton R. The natural history of periodontal attachment loss during the third and fourth decades of life. J ClinPeriodontol. 2013;40:672–80. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12108. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomson WM, Poulton R, Broadbent JM, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Beck JD, et al. Cannabis smoking and periodontal disease among young adults. JAMA. 2008;299:525–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.5.525. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.299.5.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antoniazzi RP, Zanatta FB, Rösing CK, Feldens CA. Association among periodontitis and the use of crack cocaine and other illicit drugs. J Periodontol. 2016;87:1396–405. doi: 10.1902/jop.2016.150732. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2016.150732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shchipkova AY, Nagaraja HN, Kumar PS. Subgingival microbial profiles of smokers with periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1247–53. doi: 10.1177/0022034510377203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034510377203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Söder B, Jin LJ, Wickholm S. Granulocyte elastase, matrix metalloproteinase-8 and prostaglandin E2 in gingival crevicular fluid in matched clinical sites in smokers and non-smokers with persistent periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:384–91. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290502.x. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-051X.2002.290502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matthews JB, Chen FM, Milward MR, Ling MR, Chapple ILC. Neutrophil superoxide production in the presence of cigarette smoke extract, nicotine and cotinine. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:626–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01894.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 1600-051X.2012.01894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leite FRM, de Aquino SG, Guimarães MR, Cirelli JA, Zamboni DS, Silva JS, et al. Relevance of the myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) on RANKL, OPG, and nod expressions induced by TLR and IL-1R signaling in bone marrow stromal cells. Inflammation. 2015;38:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-0001-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10753-014-0001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giannopoulou C, Kamma JJ, Mombelli A. Effect of inflammation, smoking and stress on gingival crevicular fluid cytokine level. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:145–53. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.300201.x. https://doi.org/10.1034/j. 1600-051X.2003.300201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leite FRM, de Aquino SG, Guimarães MR, Cirelli JA, Junior CR. RANKL expression is differentially modulated by TLR2 and TLR4 signaling in fibroblasts and osteoblasts. Immunol Innov. 2014;2:1. Doi:10.7243/2053-213X-2-1. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Söder B, Airila Mansson S, Soder PO, Kari K, Meurman J. Levels of matrix metalloproteinases-8 and -9 with simultaneous presence of periodontal pathogens in gingival crevicular fluid as well as matrix metalloproteinase-9 and cholesterol in blood. J Periodontal Res. 2006;41:411–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2006.00888.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 1600-0765.2006.00888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu KZ, Hynes A, Man A, Alsagheer A, Singer DL, Scott DA. Increased local matrix metalloproteinase-8 expression in the periodontal con- nective tissues of smokers with periodontal disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:775–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.05.014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Persson L, Bergström J, Ito H, Gustafsson A. Tobacco smoking and neutrophil activity in patients with periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2001;72:90–95. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.1.90. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2001.72.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palmer RM, Wilson RF, Hasan AS, Scott DA. Mechanisms of action of environmental factors—tobacco smoking. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32((Suppl 6)):180–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00786.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 1600-051X.2005.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poggi P, Rota MT, Boratto R. The volatile fraction of cigarette smoke induces alterations in the human gingival fibroblast cytoskeleton. J Periodontal Res. 2002;37:230–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2002.00317.x. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0765.2002.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeng J, Williams SM, Fletcher DJ, Cameron CM, Broadbent JM, Shearer DM, et al. Reexamining the association between smoking and periodontitis in the dunedin study with an enhanced analytical approach. J Periodontol. 2014;85:1390–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2014.130577. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2014.130577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nascimento GG, Peres MA, Mittinty MN, Peres KG, Do LG, Horta BL, et al. Diet-induced overweight and obesity and periodontitis risk:An application of the parametric G-formula in the 1982 pelotas birth cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185:442–51. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww187. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kww187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kristman V, Manno M, Cote P. Loss to follow-up in cohort studies:How much is too much?Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19:751–60. doi: 10.1023/b:ejep.0000036568.02655.f8. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:EJEP.0000036568.02655.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Young AF, Powers JR, Bell SL. Attrition in longitudinal studies:Who do you lose? Aust N Z J Public Health. 2006;30:353–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2006.tb00849.x. https://doi. org/10.1111/j0.1467-842X.2006.tb00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Albandar JM. Underestimation of periodontitis in NHANES surveys. J Periodontol. 2011;82:337–41. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.100638. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2011.100638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holtfreter B, Albandar JM, Dietrich T, Dye BA, Eaton KA, Eke PI, et al. Standards for reporting chronic periodontitis prevalence and severity in epidemiologic studies:Proposed standards from the joint EU/USA periodontal epidemiology working group. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42:407–12. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12392. https://doi. org/10.1111/jcpe.12392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goodson JM, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. The relationship between attachment level loss and alveolar bone loss. J Clin Periodontol. 1984;11:348–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1984.tb01331.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.1984.tb01331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jeffcoat MK, Reddy MS. Progression of probing attachment loss in adult periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1991;62:185–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.3.185. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.1991.62.3.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Corraini P, Baelum V, Lopez R. Reliability of direct and indirect clinical attachment level measurements. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40:896–905. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12137. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]