Abstract

The purpose of this article is to share a Canadian model called Developing a Compassionate Community (DCC) in which aging, dying, caregiving, and grieving are everyone’s responsibility. The model provides a research-informed practice guide for people who choose to adopt a community capacity development approach to developing a compassioante community. Based on 30 years of Canadian research by the author in rural, urban, First Nations communities, and long-term care homes, the DCC model offers a practice theory and practical tool. The model incorporates the principles of community capacity development which are as follows: change is incremental and in phases, but nonlinear and dynamic; the change process takes time; development is essentially about developing people; development builds on existing resources (assets); development cannot be imposed from the outside; and development is ongoing (never-ending). Community capacity development starts with citizens who want to make positive changes in their lives and their community. They become empowered by gaining the knowledge, skills, and resources they need. The community mobilizes around finding solutions rather than discussing problems. Passion propels their action and commitment drives the process. The strategy for change is engaging, empowering, and educating community members to act on their own behalf. It requires mobilizing networks of families, friends, and neighbors across the community, wherever people live, work, or play. Community networks are encouraged to prepare for later life, and for giving and getting help among themselves. This Canadian model offers communities one approach to developing a compassionate community and is a resource for implementing a public health approach to end-of-life care in Canada. The model is also available to be evaluated for its applicability beyond Canada and is designed to be adapted to new contexts if desired.

Keywords: community capacity development, compassionate communities, end-of-life care, First Nations, long-term care homes, participatory action research, practice model, public health palliative care, rural, social work competencies, theory of change

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to share a Canadian model called Developing a Compassionate Community (DCC). The DCC model is the fourth and newest version of a community capacity development model often known as the Kelley model, or simply as the ‘Tree Model’. Created in 2017, this model provides a research-informed practice guide for people who choose to adopt a community capacity development approach to developing a compassioante community. Based on 30 years of Canadian research by the author in rural, urban, First Nations communities, and long-term care homes, the DCC model offers a resource for implementing a public health approach to end-of-life care in Canada.

The DCC model provides a theory of change for community capacity development. It uses concepts to explain the change process that communities go through as they organize to improve care for people who are dying. As with any theory, the goal is to describe what has happened in the past and describe what is expected to occur in a future situation. Thus, the DCC model offers a tool to guide future practice of compassionate community development in Canada.

The DCC model is based on multiple, diverse Canadian communities studied by the author since 1992. It synthesizes the key processes and elements of these communities’ experience as they developed their capacity to provide palliative end-of-life care. The Kelley model evolved over the years to reflect additional learnings and different community contexts. The composite and evolutionary nature of its development makes the DCC model applicable to provide inspiration and general guidance about the community capacity development approach in the context of end-of-life care. The DCC (DCC needs to be italics throughout the paper for consistency) model is also flexible and dynamic, consistent with capacity development principles. Thus, the DCC model can be a helpful resource to Canadian communities of different sizes, cultures, or locations.

The DCC model depicts a ‘bottom-up’ community development approach that builds on existing community resources and remains community focused. This approach assumes communities can creatively solve their problems using a process of collective problem-solving.1 –3 Community development involves identifying each community’s unique strengths and assets and then ‘building on what already exists’.1 –3 The method for change is to enhance existing capacities and not impose solutions from outside the community.1 –3 It is also an ‘inside-out’ process. The leadership and catalyst for change (usually an impactful experience) come from within the community; outsiders can assist if requested in the roles of facilitator, organizer, or connecting the community with resources.

The ‘bottom-up’ and ‘inside-out’ approach of the DCC model is consistent with other community capacity development models in international literature. However, it differs from other community capacity development models in that it focuses specifically on palliative care and end-of-life issues. It also differs from models for developing health services as it includes a much broader understanding of community, extending beyond health and social care professionals, and formal services. Incorporating social services and natural helping networks is important for championing a social model of end-of-life care where aging, dying, caregiving, and grieving are everyone’s responsibility.

The DCC model also differs from other community capacity development models in that it depicts more than the process of change (i.e. the specific phases of community development). It also incorporates the key elements that determine a community’s readiness to begin development. Community readiness is a prerequisite to a successful bottom-up change process. Finally, the DCC model includes the five streams of activities relevant to compassionate community work, highlighting the importance of incorporating community values to guide the work. This makes the DCC model a comprehensive guide for communities undertaking compassionate community development.

Many countries have initiated compassionate community strategies to support people at the end of life, for example, Ireland, 4 Austria, 5 India, 6 Australia, 7 Columbia, 8 Spain, 9 the United States, 10 Canada, 11 and England. 12 The DCC model contributes a conceptual resource to the growing international compassionate community literature. It offers a research-informed practice theory and guide for communities seeking a road map as they build community capacity to care for people dying at home in their own unique context. The DCC model also contributes practical knowledge to the compassionate community movement internationally.

The DCC model is intended to be used to guide people in their thinking about developing compassionate communities. It is not intended to be prescriptive, but rather it can be adapted to a community’s unique circumstances. There is no requirement to ask for permission. Public Health Palliative Care International 13 is playing an important role in sharing promising practices and practice theory.

Background

The earliest version of Kelley’s model was created based on data collected through focus groups conducted in seven provinces and territories across Canada (1999–2000). The research goal was to understand and describe how healthcare providers in rural and remote communities that lacked palliative care services had successfully worked with their community to provide care for people who were dying. 14 Community capacity development is an accepted practice approach for health promotion in rural, remote, and underserviced areas of the world. Therefore, Kelley drew on the international literature on community capacity development 15 and used these principles as the lens to view the collected data.

The outcome of that analysis was a model, called Developing Rural Palliative Care (2007). 16 The rural model was refined and validated through subsequent research. 17 It is accepted as a practice theory to guide developing palliative care in rural, remote, and underserviced areas of Canada and is a practical guide for use in rural communities. 18

In subsequent years, Kelley’s research on community capacity development extended beyond rural communities and the model evolved to incorporate new learnings. She conducted participatory action research with First Nations communities19,20 and frontline staff in long-term care homes21,22 to improve care for people at the end of life. Using her model as a conceptual guide and working directly with community members, Kelley and her research teams were able to understand and document their process of community change. Data from observations, interviews, and focus groups were used to adapt the model to reflect the unique community context and community culture. An adapted model was always co-created with the community members and customized to fit local circumstances. As an outcome of this research, there are versions of Kelley’s model called Developing Palliative Care in First Nations Communities 23 and Developing Palliative Care in Long-Term Care Homes. 24

Over her years of community-based participatory action research, Kelley’s data convincingly demonstrated that the ‘palliative care community’ extended well beyond healthcare professionals to include natural helpers, frontline health and social care providers, formal and informal community leaders, and social services. These findings empirically supported that communities operated using a social model of care. The following quote illustrates this:

At initial formation of the palliative care team in the [5 rural] communities studied, membership was made up of a very broad range of service providers and community members, including health care professionals, mental health workers and hospice volunteers, as well as clergy, funeral directors, lawyers, and ambulance drivers. The breadth of community members who volunteered for a new team showed the interest and importance of palliative care in these communities, as well as confirming that palliative care inspired a holistic and inclusive community-focused approach. (p. 4) 25

The author was introduced to Dr Allan Kellehear in 2012 and became inspired by the emerging compassionate community literature.26 –29 A significant influence for the author was attending her first Public Health Palliative Care Conference in 2015 (England). She immediately embraced the concept of compassionate communities and the social model of palliative care which aligned with her Canadian experience in rural, First Nations, and long-term care homes and her social work perspective. Community capacity development was an accepted Social Work Competency for Palliative care in Canada. 30

In 2015, the author became a Compassionate Ottawa volunteer and began to apply and adapt her conceptual model to capture the experience of developing a compassionate community. The DCC model was created by participating, observing, and learning from the experience of Compassionate Ottawa (Ottawa, Canada), 31 Hospice Northwest (Thunder Bay, Canada), 32 and other compassionate community initiatives. By 2021, the DCC model has evolved to become as presented in this article.

The DCC model

The author chose the tree as a visual image to represent community capacity development. Trees, like communities, share many common characteristics; however, there are many different kinds. Trees are also organic and grow slowly from the bottom up. You cannot grow a tree from the top down!

The rate of a tree’s growth is greatly affected by conditions in the environment. Growth can be nurtured by sufficient rain and sun or stunted without it. Trees can die if the conditions are poor.

The invisible conditions in the soil (like nutrients) determine the potential (readiness) for successful growth. Growth to maturity takes time and the process of growth and change is dynamic and never-ending. Trees thrive best in a forested ecosystem where they give support to one another. Thus, the tree is an appropriate metaphor for compassionate community development.

The model incorporates the principles of community capacity development. Community capacity development is a process of bottom-up social change. It starts with citizens who want to make positive changes in their lives and their community. Individuals and groups become empowered by gaining the knowledge, skills, and resources they need. The community mobilizes around finding solutions rather than discussing problems. Passion drives the action and commitment fuels the process.

The catalyst for change is local leaders who have an inspiring vision and can mobilize other people around them. Community capacity development builds on local community strengths, respects community values and beliefs, and draws on a broad range of local community resources (social, cultural, educational, economic, and health). Because of this, the specifics of the development process are unique in each community.

The pace of change is determined by the readiness of the community and the ability of local leaders to generate collaborations, mobilize a group of like-minded champions, and manage barriers. The strategy for change is engaging, empowering, and educating community members to act on their own behalf. It requires engaging and mobilizing networks of families, friends, and neighbors across the community, wherever people live, work, or play. Community networks are encouraged to prepare themselves for later life and for giving and getting help to their family, friends, and neighbors.

Capacity development differs from providing services in that community members determine their needs and create their own solutions. The focus is on self-help and helping each other (mutual aid). Outsiders (when involved) provide help or expertise in a collaborative role. Experts such as healthcare professionals are partners in the process.

While external facilitators can help the community to organize themselves, they do not control the process. Community ownership sustains commitment. Development is always doing things WITH the community, and not doing things FOR the community. Thus, the change process in capacity development is not only bottom-up but it is inside-out.

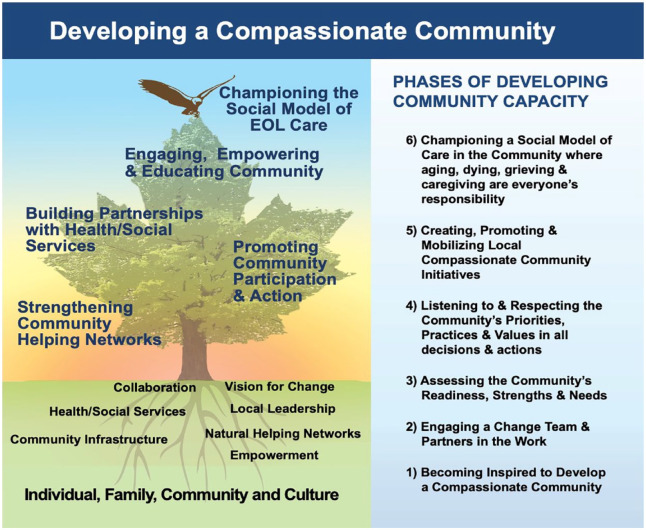

The model is graphically presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

DCC: the model.

Overview of the model

The model has four components (presented from bottom to top):

The community environment: Eight elements that shape development and determine a community’s readiness for change (shown below soil, in the roots of the tree)

The activities in a compassionate community: Five activity streams (shown in the foliage of the tree)

The eagle at the treetop: Community values that guide the work

The phases of developing community capacity: Six phases of development (bottom-up, shown in the side panel on the right)

Each of these four components is now explained.

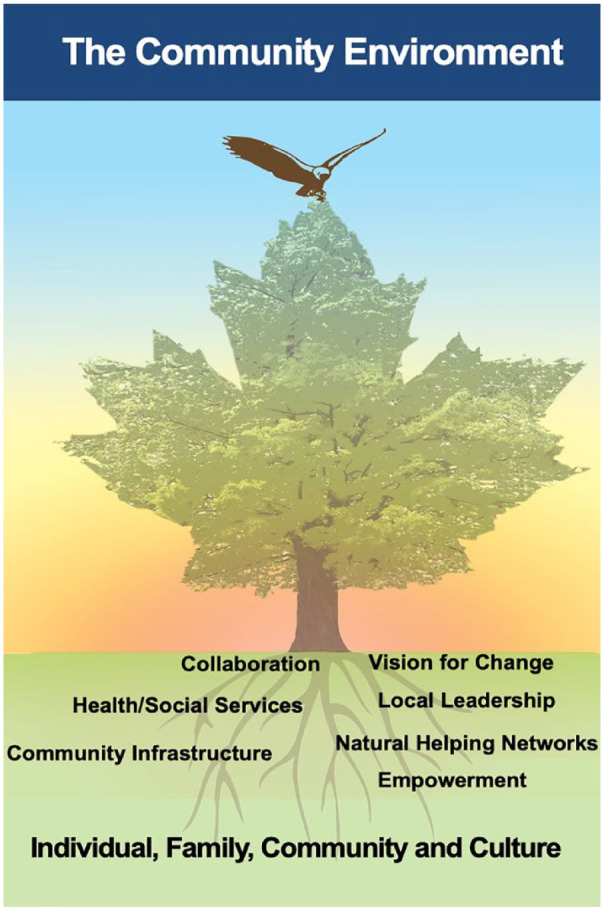

The community environment

The model describes eight elements that together shape the compassionate community development process and determine the readiness for change. In the diagram, they are shown below the soil line, in the roots of the trees (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The community environment.

The eight elements are as follows:

-

Individual, family, community, and culture:

The work of developing a compassionate community requires a deep understanding of the current values, beliefs, perspectives, and priorities of community members related to end-of-life issues. Find out: What are the current practices of individuals, families, and communities when someone is caregiving, dying, or grieving? What is culturally appropriate? Previous research has shown that successful capacity development respects and adapts to individuals, families, communities, and cultures.16,17,19,33

-

Vision for change:

Having a strong, compelling vision for change is essential. The vision motivates others to become involved. Powerful visions usually come from the lived experiences of community members. Either their good experiences or their bad experiences can catalyze change. Previous research has shown that in communities where people are generally content with their current situation, they do not see the need for developing a compassionate community.16 –19 Progress in that case is unlikely.

-

Local leadership:

Having strong local leaders is essential. They need to be well-respected in the community and well-connected with others. These leaders will have the ability to mobilize a group of people and will be able to create partnerships and collaborations. Previous research has shown that where leadership comes from outside the community (not inside), little progress is made, and the community does not take responsibility.16 –19,25

-

Empowerment:

The goal of community capacity development is to prepare and mobilize people to act on their own behalf. Community members need to be motivated to solve their problems and to make changes in the community that will benefit them. They need to believe that death and dying are everyone’s responsibility. They need to be willing to commit to change. Previous research has shown that in communities that want professionals and health services to take responsibility for end-of-life issues, little progress will be made to develop a compassionate community.16,17,19,25

-

Natural helping networks:

It is the family and community who provide 95% of the care and support to people who are seriously ill, dying, grieving, and caregiving. The network of people who rally around a person or family is often called their natural helping network. Recognizing, encouraging, strengthening, and supporting these networks is an important role in a compassionate community. Previous research has shown that communities with strong natural helping networks are most successful in becoming compassionate communities.16,17,19

-

Collaboration:

Compassionate community development requires collaboration and partnerships with individuals, groups, organizations, local government, businesses, and more. Collaboration is how the vision spreads, and a social movement gets created. Compassionate community work can happen everywhere people in the community live, work, or play. Previous research has shown that communities with the broadest and strongest collaborations are the most successful in creating a social movement.16 –19,25 A social movement is an organized effort involving the mobilization of large numbers of people to work together to create a desired change.

-

Health and social services:

Health and social services continue to play an important role in a compassionate community. Although the community provides 95% of end-of-life care and support, the specialized knowledge and resources of health and social services remain very important. Communities lacking health and social services face a greater challenge supporting people at the end of life. Previous research has shown that communities without accessible, effective health services and social care are less confident and are less able to provide community care to the end of life.16,17,19

-

Community infrastructure:

Community infrastructure means the buildings and spaces that provide services, activities, and opportunities for people. Some examples include public parks, schools, recreation facilities, clean and safe water, good roads, and public transportation. People living in communities with good infrastructure experience better overall community health, well-being, and quality of life. Previous research has shown that communities lacking infrastructure have more challenges providing community care to the end of life.16,17,19

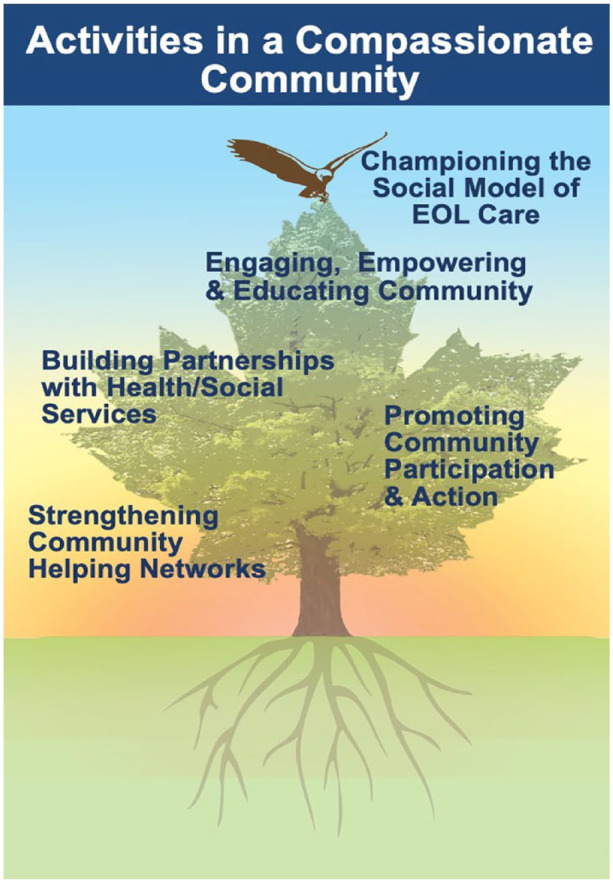

The activities in a compassionate community

The model describes a fully developed compassionate community as having five activity streams. The activity streams are depicted in the foliage of the mature, fully developed tree. However, these activity streams will develop gradually over time, following the bottom-up and inside-out processes described. The activity steams can also interact in practice (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Activities in a compassionate community.

The activities of a compassionate community are as follows:

Promoting community participation and action

Strengthening community helping networks

Engaging, empowering, and educating community members

Building partnerships with health and social services

Championing a social model of end-of-life care

The order and way these activities evolve will vary by community, depending on local priorities and opportunities. Activities will likely come on stream gradually over several years at a pace determined by community readiness and available resources. Communities set their own priorities. Activity streams are ongoing (never-ending). The specifics of the work in each activity stream will vary over time, and from place to place. Examples of these activity streams can be found on the Compassionate Ottawa 31 and Hospice Northwest 32 websites.

The eagle at the treetop – Community values that guide the work

The values that guide the community development process are represented by the eagle landing on the top of the tree. Values have the highest position on the model because values are overarching in compassionate community work. Community values shape the vision of their compassionate community. Shared values inspire, motivate, and mobilize the community members who will work to create change.

Values shape all the activities undertaken. Everything done in the compassionate community development process should align with community values. That is why, in the end, no two compassionate communities will be exactly alike. Each compassionate community must develop in a way that respects its individual, family, community, and cultural values. Diversity and inclusivity need to be considered.

The eagle (community values) was added to the model in 2011 by First Nations communities. To the First Nations involved, the eagle on top of the tree represents a spiritual being that warns of impending danger and is a symbol of strength. The eagle watches over all and is a connection to the Creator. In many cultures and throughout human history, the eagle has been a symbol of vision, strength, resilience, perspective, courage, spirituality, and power. Every community should determine what the eagle represents to them or replace this symbol with one more meaningful to them.

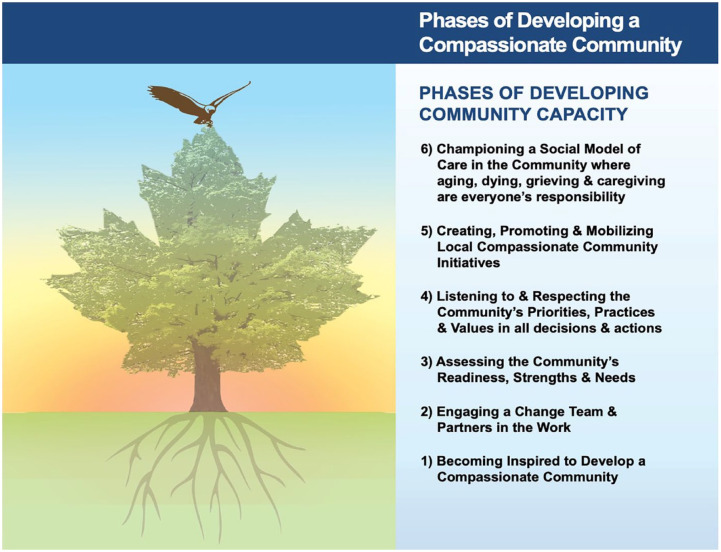

The phases of DCC

The model is sequential and is described in six phases, from the bottom to the top. That is because community capacity development is a bottom-up process. At the same time, the development process is dynamic and evolutionary, not rigid, or linear. Phases blend into one another. Work in each phase is also ongoing, that is, it is never complete. For example, while the first phase of inspiration would precede getting people working on compassionate community initiatives, the need to keep people inspired is ongoing. Assessing the community is also ongoing as needs and resources of the community change over time.

The pace of movement from one phase to the next is influenced by the community environment. Opportunities and supports can speed up movement through the phases. Barriers can slow things down since these barriers need to be managed before moving on. Change is gradual but incremental (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Phases of Developing a Compassionate Community.

DCC, Developing a Compassionate Community.

Phase 1: Becoming inspired to develop a compassionate community

Inspiration is the catalyst for change in compassionate community work. It can be the inspiration of one person or a group of people who want to create change for people in their community at the end of life. Inspiration usually comes from an impactful life experience that acts as a catalyst and causes that person or group to want to mobilize others to join them. The impactful experience can be the death of a loved one, education, or attending a compassionate community event. The catalyst is always personal and powerful.

Phase 2: Engaging a change team and partners in the work

Once inspired, the next phase involves engaging a larger group of community people who are committed to working together to achieve a shared vision for developing a compassionate community. Ideally, the initial group includes ‘influencers’, meaning people who are respected in the community and others will follow. Community organizations are ideal places to start engagement (e.g. community centers, recreational groups, cultural associations). Organizational partners can also be very valuable to engage right at the beginning. Partners could have relevant experiences such as community development, caregiving, or end-of-life issues. Partners may have access to resources such as meeting space or help give the citizen group credibility. It is important, however, that the community members continue to drive the process.

Phase 3: Assessing the community’s readiness, strengths, and needs

This phase involves doing a scan of the community environment. How ready is the community for this work? This involves considering the eight elements of the community environment outlined in the model. It requires time spent observing, deeply listening, and reflecting before acting. For compassionate community development to be successful, activities must meet the needs of many community members. Doing the environmental scan further helps identify facilitators and barriers to change and can inform where to begin work or indeed if the time is right to begin compassionate community work.

Phase 4: Listening to and respecting the community priorities, practices, and values in all decisions and actions

The compassionate community vision must be consistent with community values, culture, and priorities. The vision must build on and celebrate the strengths in the community, such as natural helping networks and caregiving practices. Consideration also needs to be given to competing priorities in the community. To engage, the community members need to be motivated and have the capacity to get involved. Any planning must consider this. For example, is social isolation, poverty, or lack of affordable housing a more pressing issue for people? If so, how can compassionate community work also address people’s priority needs?

Phase 5: Creating, promoting, and mobilizing compassionate community initiatives

This phase is where the grassroots community work begins, assuming the readiness of the community. Most communities are not homogeneous. Communities are usually organized into smaller communities by geography (neighborhoods), culture or language, or shared interests such as art or recreation. Thus, there are many communities within communities. Some communities may be ready and others not. Work can begin with those who demonstrate interest. Community development is an incremental process, built on many small initiatives. If these initiatives are all consistent with the overall vision, then they will all be heading toward the same outcome and merge over time. Evaluation is a valuable tool to ensure work is on track. The evaluation also gathers evidence of success for use in phase 6.

Phase 6: Championing a social model of care in the community where aging, dying, grieving, and caregiving are everyone’s responsibility

Building on the work underway in phase 5, this phase focuses on celebrating successes, disseminating examples, and promoting messages about compassionate community work. Other community members learn from seeing successes and the benefits of the social model of care. Ideas can spread through personal contact and sharing stories. Promoting community awareness can also be done through community events, media (social media and traditional media), websites, digital stories, and many other ways. Community partners can be valuable allies in giving messages a broad reach. Health and social service providers and organizations should be engaged, and this can strengthen collaborations. Government leaders at the municipal, provincial, and federal levels should also be engaged to influence social policy.

Conclusion

The DCC model provides a conceptual model of community change that advances a social model of end-of-life care. The development process described in the model is independent of any unique community or sociocultural context. In fact, according to the model, development grows out of each community’s specific strengths and resources, and it builds on the capacities of the local people who are engaged in developing a compassionate community.

The model clearly demonstrates the principles of capacity development which are as follows: change is incremental and in phases, but nonlinear and dynamic; the change process takes time; development is essentially about developing people; development builds on existing resources (assets); development cannot be imposed from the outside; and development is ongoing (never-ending).

This Canadian model offers communities an approach to thinking about developing a compassionate community. It can help guide compassionate community development in Canada. It is also available to be evaluated for its applicability beyond Canada and adapted to fit new contexts if desired.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the commitment and achievements of the many Canadian community members who have mobilized their communities to improve end-of-life care and generously shared their wisdom with me. This includes members of rural communities, First Nations communities, long-term care homes, and Compassionate Community initiatives across Canada. I would especially like to acknowledge the contribution of Compassionate Ottawa, Ottawa, and Hospice Northwest, Thunder Bay, to the ideas in this article. They have all demonstrated that compassion lives in all of us and it is possible to nurture the growth of compassionate communities wherever you live and work.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Mary Lou Kelley  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5873-5208

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5873-5208

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable.

Consent for Publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Mary Lou Kelley: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and materials: Not applicable.

References

- 1. Raeburn J, Akerman M, Chuengsatiansup K, et al. Community capacity building and health promotion in a globalized world. Health Promot Int 2006; 21: 84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McKnight JL, Russell C. The four essential elements of an asset-based community development process. Asset-based Community Development Institute. Report. DePaul University, https://www.sivioinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/Public_Policy_School/Course_Reader/12_Asset_Based_Approaches_to_Policy_Advocacy/4-Essential-Elements-of-ABCD-Process.pdf (2018, accessed 28 June 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Horton JE, MacLeod MLP. The experience of capacity building among health education workers in the Yukon. Can J Public Health 2008; 99: 69–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McLoughlin K, Rhatigan J, McGilloway S, et al. INSPIRE (INvestigating Social and Practical supports at the End of life): pilot randomized trial of a community social and practical support intervention for adults with life-limiting illness. BMC Palliat Care 2015; 14: 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wegleitner K, Schuchter P. Caring communities as collective learning process: findings and lessons learned from a participatory research project in Austria. Ann Palliat Med 2018; 7: S84–S98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sallnow L, Kumar S, Numpeli M. Home-based palliative care in Kerala, India: the neighbourhood network in palliative care. Prog Palliat Care 2010; 18: 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rosenberg JP, Horsfall D, Leonard R, et al. Informal caring networks for people at end of life: building social capital in Australian communities. Health Social Rev 2015; 24: 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Librada Flores S. A new method for developing compassionate communities and cities movement-“Todos Contigo” Programme (We are All With You): experience in Spain and Latin America countries. Ann Palliat Med 2018; 7: AB004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gómez-Batiste X, Mateu S, Serra-Jofre S, et al. Compassionate communities: design and preliminary results of the experience of Vic (Barcelona, Spain) caring city. Ann Palliat Med 2018; 7: S32–S41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lown B. Seven guiding commitments: making the U.S. healthcare system more compassionate. J Patient Exp 2014; 1: 6–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pesut B, Duggleby W, Warner G, et al. Volunteer navigation partnerships: piloting a compassionate community approach to early palliative care. BMC Palliat Care 2017; 17: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abel J, Bowra J, Howarth G. Compassionate community networks: supporting home dying. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2011; 1: 129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Public Health Palliative Care International, https://www.phpci.org/tools (accessed 23 March 2023).

- 14. MacLean M, Kelley ML. Palliative care in rural Canada. Rural Soc Work 2001; 6: 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Norton BL, McLeroy KR, Burdine JN, et al. Community capacity: concept, theory and methods. In: Clementi RD, Crosby R, Kegler M. (eds) Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2002, pp.194–227. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kelley ML. Developing rural communities’ capacity for palliative care: a conceptual model. J Palliat Care 2007; 23: 143–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kelley ML, Williams A, DeMiglio L, et al. Developing rural palliative care: validating a conceptual model. Rural Remote Health 2011; 11: 1717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kelley ML, DeMiglio L, Williams A, et al. Community capacity building in palliative care: an illustrative case study in rural Northwestern Ontario. J Rural Community Dev 2012; 7: 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kelley ML, Prince H, Nadin S, et al. Developing palliative care programs in Indigenous communities using participatory action research: a Canadian application of the public health approach to palliative care. Ann Palliat Med 2018; 7: S52–S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nadin S, Crow M, Prince H, et al. Wiisokotaatiwin: development and evaluation of a community-based palliative care program in Naotkamegwanning First Nation. Rural Remote Health 2018; 18: 4317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marcella J, Kelley ML. Death is part of the job in long term care homes: supporting direct care staff with their grief and bereavement. Sage Open 2015; 5: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kelley ML. Palliative Alliance Research Team, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, ON Canada. Quality Palliative Care in Long Term Care: Tools and Resources for Organizational Change, https://www.palliativealliance.ca/ (accessed 23 March 2023).

- 23. Kelley ML. Improving End of Life Care in First Nations Communities Research Team, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay ON Canada. Process of palliative care development in First Nations communities, https://eolfn.lakeheadu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Palliative-Care-Workbook-Final-December-17.pdf (2015, accessed 23 March 2023).

- 24. Kelley ML. Palliative Alliance Research Team, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, ON Canada. Kelley model for palliative care capacity development in long term care homes, https://www.palliativealliance.ca/applying-the-kelley-model-for-community-capacity-development.html (2018, accessed 23 March 2023).

- 25. Gaudet A, Kelley ML, Williams AM. Understanding the distinct experience of rural interprofessional collaboration in developing palliative care programs. Rural Remote Health 2014; 14: 2711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kellehear A. Compassionate cities: public health and end of life. London and New York; Routledge, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sallnow L, Kumar S, Kellehear A. International perspectives on public health and palliative care. London and New York; Routledge, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cohen J, Deliens L. (eds). A public health perspective on end of life care. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abel J, Walter T, Carey LB, et al. Circles of care: should community development redefine the practice of palliative care? BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013; 3: 383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bosma H, Johnston M, Cadell S, et al. Creating social work competencies for practice in hospice palliative care. Palliat Med 2010; 24: 79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Compassionate Ottawa, www.compassionateottawa.ca/ (accessed 27 June 2023).

- 32. Hospice northwest, https://www.hospicenorthwest.ca/ (accessed 27 June 2023).

- 33. Russell C. Understanding ground-up community development from a practice perspective. Lifestyle Med 2022; 3: e69. [Google Scholar]