Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to create and develop a well-designed, theoretically driven, evidence-based, digital, decision Tool to Empower Parental Telling and Talking (TELL Tool) prototype.

Methods

This developmental study used an inclusive, systematic, and iterative process to formulate a prototype TELL Tool: the first digital decision aid for parents who have children 1 to 16 years of age and used donated gametes or embryos to establish their families. Recommendations from the International Patient Decision Aids Standards Collaboration and from experts in decision aid development, digital health interventions, design thinking, and instructional design guided the process.

Results

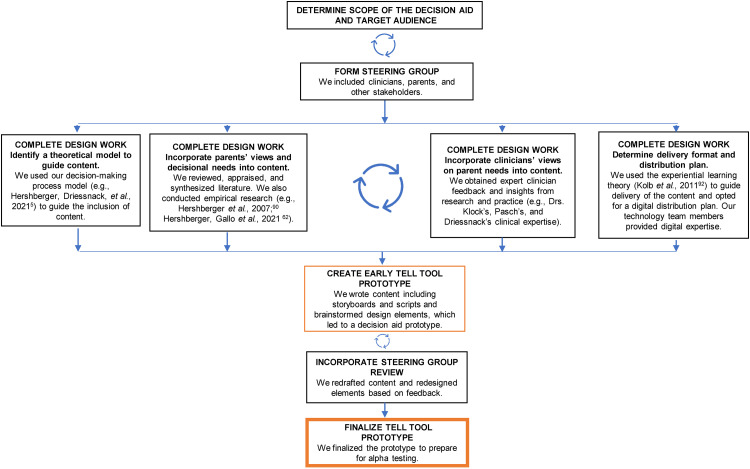

The extensive developmental process incorporated researchers, clinicians, parents, children, and other stakeholders, including donor-conceived adults. We determined the scope and target audience of the decision aid and formed a steering group. During design work, we used the decision-making process model as the guiding framework for selecting content. Parents’ views and decisional needs were incorporated into the prototype through empirical research and review, appraisal, and synthesis of the literature. Clinicians’ perspectives and insights were also incorporated. We used the experiential learning theory to guide the delivery of the content through a digital distribution plan. Following creation of initial content, including storyboards and scripts, an early prototype was redrafted and redesigned based on feedback from the steering group. A final TELL Tool prototype was then developed for alpha testing.

Conclusions

Detailing our early developmental processes provides transparency that can benefit the donor-conceived community as well as clinicians and researchers, especially those designing digital decision aids. Future research to evaluate the efficacy of the TELL Tool is planned.

Keywords: Decision support techniques, disclosure, donor conception, gamete donation, parent–child relationship, patient decision aids, third-party reproduction

Introduction

Given the long history of secrecy surrounding donor conception—often promulgated by clinicians with the goal of protecting future parents and their donor-conceived offspring from stigma and even claims of unlawful birth1,2 —it is not surprising that many parents who successfully use donated gametes (sperm and eggs) or embryos find that informing their child(ren) about their genetic origins is challenging.

To demonstrate this point, a systematic review and meta-analysis examined 26 studies that included 2814 parents and compared those who underwent medical reproduction (e.g. in vitro fertilization) with their own (i.e. autologous) gametes to those who underwent medical reproduction using donated gametes or embryos. 3 The investigators found that only 23% of the total sample of parents had told their children about the origins of their conception; among the subgroups of parents, 23% of donor egg, 21% of donor sperm, and 11% of donor-embryo recipients reported having told their children about how they came to be. 3 Moreover, US parents who use donor gametes find that it becomes increasingly difficult to tell their children about their origins even and despite early intentions to do so.4,5 There are now well-documented calls from both parents and clinicians for information on appropriate timing of when to tell and for more strategies and tools for how to tell children about their origins.4,6–8

Multiple professional organizations currently endorse telling children about their genetic origins.9–11 Meanwhile, direct-to-consumer genetic tests (e.g. 23andMe and Ancestry) have ushered in a radical change that allows individuals to trace their genetic origins with relative ease. Coupled with the exponential growth of social networking sites (e.g. Facebook and Instagram), these modern technological developments have and will continue to make secrecy only an illusion for parents.12–15 In response, thought leaders have recommended a shift in psychosocial counseling from emphasizing assessment and evaluation of prospective parents to emphasizing psycho-educational partnership and strategies for building healthy families, such as information about how (prospective) parents can begin the telling process.9,16,17

Other developments in the move toward openness is the promotion of knowledge about genetic heritage, which is increasingly important for health histories and personalized medicine—defined as “an emerging practice of medicine that uses an individual's genetic profile to guide decisions made in regard to the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of disease.” 18 An accurate health history remains the least expensive and most universal, accessible, and practical genetic risk assessment tool. 19 Recommendations to increase its use and implementation, including expanding lay education about the importance of inherited genetic risks, are underway.19–21 Reports about parents being prompted to tell their offspring about their genetic origins because of genetically related health issues that arise are also surfacing. 22 Identity development, in regards to the ability of donor-conceived people to understand themselves through knowledge of where their traits are from, has also been mentioned in the literature as an extenuating factor in the move toward openness about genetic origins. 23

Patient decision aids and digital health resources

Decision aids are tools used to inform people who want to actively participate in health decision-making. They have been found to help people feel more knowledgeable, better informed, and clearer about their values and thus to help them think about their options from a personal view. 24 As the field of decision aids expanded, an International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration was formed to provide recommendations for reporting on the developmental process of decision aids. 25

Digital health is a burgeoning field of practice for innovative forms of information and communication that address a variety of health needs. Digital health encompasses a broad scope of technologies, including mobile Health (mHealth), electronic Health (eHealth), and biosensors.26,27 Increases in internet access and smartphone use worldwide have allowed for a vast array of digital health applications across populations and communities.26,28 While digital technologies were already transforming health care pre-COVID-19, 28 the post-COVID-19 era has provided even more opportunities for digital health. 26

When digital technology is combined with decision aids, a broad range of features can be used to help people think about their preferences and their role in the decision-making process. Such features include text, images, digital media such as audio and video clips, animation, and other interactive and personalized features. 29 A key characteristic of these digital tools is that they offer the convenience of accessibility: people can choose to use them almost anywhere, at any given time, and in the privacy of their homes. 30

Need for resources for donor-recipient parents

Recent recommendations from the ESHRE Working Group on Reproductive Donation 9 call for clinicians to provide resources to support parents and inform them about how they can talk with their children, using age-appropriate language, about their children's genetic origins. Several resources already exist for prospective and successful donor-recipient parents to assist them in the telling process. For over 25 years, the Donor Conception Network, a support group based in the United Kingdom, has offered workshops for members along with a variety of educational materials including a wide range of children's story books for purchase by members and nonmembers. 31 Another resource is the government-funded “Time to Tell” campaign in Victoria, Australia, which provides various educational materials to donor-recipient parents.32,33 There is also a growing number of books (e.g. Let's Talk About Egg Donation 34 ) and websites (e.g. National Network of LGBTQ Family Groups 35 ) aimed at supporting parents to talk about their experiences with donor gamete and embryo use. However, to our knowledge, there are no existing research-based or digital health resources that will systematically assist parents with the decision-making process surrounding telling their children about their genetic origins or collect data to better understand and examine parents’ telling processes.

The purpose of this paper is to describe the rigorous developmental process that was implemented to create the prototype of the digital Tool to Empower Parental Telling and Talking (TELL Tool), as recommended by the IPDAS Collaboration for reporting standards for patient decision aids. 25

Methods

Ethical approval

The University of Illinois Chicago and the University of Michigan Institutional Review Boards (Protocols #2020-1086 and #HUM00230985, respectively) approved the development of the TELL Tool prototype (i.e. TELL Tool) as part of a larger program of research where we also implemented alpha testing of the tool. The findings from our alpha test are reported elsewhere. 36 Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation in the study.

Study design and methods

Statistical analysis. Our iterative developmental process incorporated the IPDAS Collaboration standards 25 and exemplars 37 along with recommendations for developing digitally delivered (electronic and web-based) decision aids 38 as guidelines for developing the TELL Tool. Additional recommendations for digital health interventions and decision aids39,40 were reviewed, considered, and incorporated as appropriate. We drew heavily on Coulter et al.'s 41 systematic process for developing patient decision aids, in which the developmental process is broken down into smaller steps during the early stages of development. This process allowed us to create, develop, and make iterative improvements and revisions to the TELL Tool as we prepared for alpha testing. An investigative team formed in January 2020 and began the process, which continued through January 2021 (over 1 year), when the alpha test was launched. This process is depicted in Figure 1 and elaborated in the Results section below.

Figure 1.

Developmental process for creation of the TELL Tool.

Source: Adapted from Coulter A, Stilwell D, Kryworuchko J, et al. A systematic development process for patient decision aids. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013; 13 Suppl 2: S2. Reprinted with permission from BioMed Central, Ltd.

To enable a parent- and family-centered approach to developing the TELL Tool, we also incorporated the main pillars of design thinking: empathy, collaboration, and experimentation. 42 Empathy was included through understanding the emotions or reactions of parents and children by diving into their worlds and hearing how they live and what they experience. We embraced collaboration by having our investigative team and larger steering group (including the parents’ advisory board and children's advisory board) work as a team with each other and with others. And we have and will continue to embody experimentation to obtain observations in different circumstances through our prior, ongoing, and planned research. 42

Our methods also incorporated modern online instructional design for how people learn in the modern world. 43 In particular, we used Dirksen's recommendations for designing behavioral change interventions 44 to understand how parents’ decisions throughout the telling process can result in changes that benefit them and their families. Our team's experiences and insights garnered from creating and implementing CHOICES, a web-based intervention to assist young adults affected by sickle cell disease or trait with decision-making about becoming parents,45–47 and ENGAGE-IL, a web-based evidence-based platform that uses emerging technologies and cutting-edge pedagogy to improve learners’ proficiency in primary care of older adults, 48 also guided the development of the TELL Tool.

Results

Determining the scope and target audience

The first step in developing a decision aid is to determine the tool's scope and target audience. 41 After consideration of feasibility and impact, we designed the TELL Tool for a target audience of parents who live in the United States and used donated eggs, sperm, or embryos to establish their families. Our scope is to help these parents make informed and sequential decisions (e.g. about language and about where and when) that are needed when telling their 1- to 16-year-old children about their genetic origins.

Forming the steering group

Forming a steering group is the second step in decision aid development. Our steering group's members were considered based on the scope of the decision aid and its target audience (i.e. US parents) in an iterative process. All members of the multidisciplinary investigative team (e.g. nurses, psychologists, and statisticians) were also members of the steering group; all are based in the United States and are highly skilled in research and/or clinical practice. Consistent with Coulter et al.'s 41 recommendations, a parents’ advisory board and a children's advisory board were formed and included within the steering group to increase representation of relevant stakeholders. The parents’ advisory board consisted of three parents (two sperm donation recipients and one egg donation recipient) from different ethnicities, gender identities, sexual orientations, and single or coupled parent families who had informed their children about their genetic origins. The children's advisory board consisted of four children who were either donor conceived (n = 3) or adopted (n = 1) and were between 5 and 14 years of age. The parents and children were recruited to serve on their respective board through previous contact and conversations with the principal investigator (PI) (PEH) where they expressed an interest to serve. In the case of the children's advisory board, the PI also communicated with each child's parent to receive parental permission prior to the child's participation on the advisory board. Other stakeholders included two members of the donor-conceived adult community and three leaders of community-based groups or foundations within the wider donor-conceived community. The steering group also included two graduate students with expertise in computer science and/or computer engineering who were members of the study's technology team.

Completing the design work

Identifying a theoretical model to guide content. To begin the necessary design work and to develop the content for the TELL Tool, we reviewed the existing literature about factors that influence donor-recipient parents’ decisions about telling children about their genetic origins.4,49,50 We also gained insights from systematic reviews.51,52

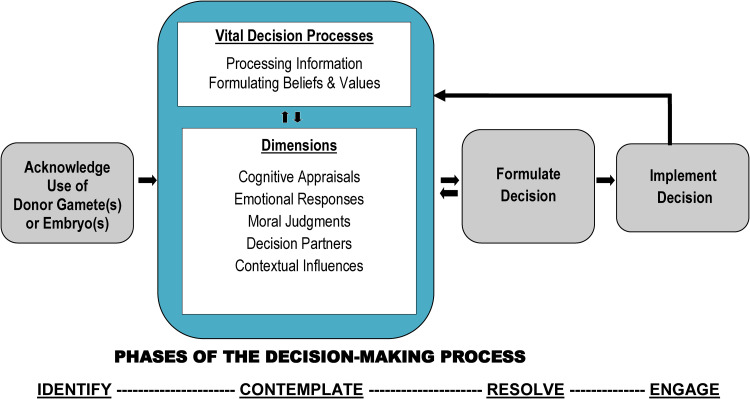

Because of the multiple and interwoven factors identified in this field, experts have specifically called for the use of explanatory theories and models to situate the underlying factors. 52 To address this gap, we validated our decision-making process (DMP) model (Figure 2), which describes intended parents’ decision processes related to preimplantation genetic diagnoses53,54 and young women's decisions about fertility preservation following a diagnosis of cancer.55,56 The DMP model was then used to explain underlying processes about donor-recipient parents’ decisions to tell or not tell their children. 5

Figure 2.

The decision-making process (DMP) model.

Sources: Adapted from Dr Hershberger's and team's research: Hershberger PE, Gallo AM, Kavanaugh K, et al. The decision-making process of genetically at-risk couples considering preimplantation genetic diagnosis: initial findings from a grounded theory study. Soc Sci Med 2012; 74: 1536–1543. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier. Hershberger PE and Pierce PF. Conceptualizing couples’ decision making in PGD: emerging cognitive, emotional, and moral dimensions. Patient Educ Couns 2010; 81: 53–62. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier. Hershberger PE, Finnegan L, Altfeld S, et al. Toward theoretical understanding of the fertility preservation decision-making process: examining information processing among young women with cancer. Res Theory Nurs Pract 2013; 27: 257–275. Reprinted with permission from Springer Publishing Company, Inc. Hershberger PE, Sipsma H, Finnegan L, et al. Reasons why young women accept or decline fertility preservation after cancer diagnosis. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2016; 45: 123–134. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

Within the contemplate phase of the DMP model (see Figure 2), there are five interrelated dimensions: cognitive appraisals (e.g. perceived risk of unintended disclosure and knowledge of how to tell the child), emotional responses (e.g. fear of harming the parent–child relationship), moral judgments (e.g. desire to protect the child and belief that secrets are harmful), decision partners (e.g. influence of partner, close family members or friends, and healthcare professionals), and contextual influences (e.g. age of the child, type of gamete used, family type, sociopolitical milieu, and religious background). 5 These five dimensions work interactively with two vital decision processes that are active during the contemplate phase: processing information and formulating beliefs and values. As we evaluated and synthesized the scientific literature, these five dimensions provided a theoretical foundation for guiding the content within the TELL Tool. Examples of TELL Tool content mapped to the five dimensions of the contemplate phase of the DMP model are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

TELL Tool content examples mapped to Kolb's experiential learning theory 57 and the decision-making process model.5,53–56

| Experiential Learning Theory: Stages and Constructs/Definitions related to the TELL Tool |

TELL Tool content examples | Decision-Making Process Model: Dimensions and Content examples within the TELL Tool |

|---|---|---|

|

Concrete experience Centering the positives and the challenges of telling |

A “welcome” video that includes children and adolescents of all ages and ethnicities precedes Module 1 to prepare parents for their decision to talk with and tell their children about their genetic origins. This video provides an opening to help parents overcome fears and see and hear from children who have normalized donor conception and are healthy and have sound relationships with their parents. |

Emotional responses Fear of harming parent–child relationships |

| A video in Module 2 shows a couple, Gabe and Rachel, who are grappling with the decision to tell their son about his donor conception. Gabe and Rachel discuss their conflicting emotions and their challenges to telling their son about his genetic origins. |

Emotional responses Specific emotions (e.g. shame and distress) presented Decision partners Role-modeling dyadic partners |

|

| Parents are asked to select the age range of their donor-conceived child, to allow the tool to tailor the information and multimedia (e.g. photos, video clips, and audio clips) presented in Module 3 to be tailored to the specific age of their child. |

Contextual influences By age of child |

|

|

Reflective observation Reflecting on and managing emotions |

Following the Gabe and Rachel video in Module 2, parents are asked to reflect on their underlying beliefs and emotions around talking with and telling their child(ren) about their donor conception. |

Moral judgments Desire to protect child and belief that secrets are harmful Emotional responses Wide range of emotions presented |

| In Module 2, parents are asked to select, from 11 colorful boxes of emotions, the emotion(s) they find most challenging in regard to telling their child about their genetic origins. After parents make their selection, the tool provides information and tips for management of each emotion selected, along with recordings of parents’ personal stories about how they managed that emotion. |

Emotional responses Impact and management of a wide range of feelings and emotions discussed |

|

|

Abstract conceptualization Thinking about creating a TELL Plan |

Parents are offered four guiding principles for telling children in Module 3 and then presented with six steps to help them organize and create their own TELL Plan based on their child's age range (1–7, 8–12, or 13–16 years of age). |

Cognitive appraisals Knowledge of how to tell the child |

| In Module 4, parents can view video clips of 14 specific situations (e.g. how to manage public vs. private information, a child's questions about the donor, direct-to-consumer genetic tests, and when to seek help) where information is provided that can help parents build confidence for their telling conversations. |

Cognitive appraisals Knowledge of what to expect after telling and information about managing subsequent telling conversions Emotional responses Increasing joy, hope, and optimism |

|

|

Active experimentation Actively creating an individualized TELL Plan |

In Module 3, parents answer embedded decision points about what to include in their TELL Plan (e.g. language, setting, and telling process). For parents to decide what to include, text, photos, cartoons, video clips of parents and specialists, and multiple opportunities to engage and think through their TELL Plan are offered. In this way, parents co-create an individualized TELL Plan that aligns with the content provided in the TELL Tool. |

Cognitive appraisals Knowledge of how to tell the child |

| In Module 4, parents can select specific situations where information about the telling process is tailored to parent's donor conception circumstances, such as when the gamete donor is a family member (e.g. a parent's sister or brother). |

Cognitive appraisals Knowledge of how to tell the child Contextual influences By type of gamete donor used |

Incorporating parents’ views and decisional needs into content. As the content for the TELL Tool was developed (guided by the five interrelated dimensions of the DMP model), we built upon our systematic review 58 by appraising the research literature for parents’ strategies, information, and outcomes of decisional needs related to the telling process. These findings were then used to create the evidence-based content for the TELL Tool. For example, Mac Dougall and colleagues 59 interviewed 141 parents who used sperm or egg donation and identified 2 strategies—seed planting and right time—that parents used to determine the timing of when to initiate the telling process with their children about their genetic origins. TELL Tool content was then written to inform parents about how to implement seed-planting and right-time strategies. Other examples of evidence-based content within the TELL Tool are that parents who have told children aged 7 and younger often give a brief, storylike description of how they needed help to have a baby60,61 and that many parents use children's books to begin or supplement their telling process.62,63

Additional examples where we identified and incorporated evidence into content were about the specific language parents use to describe the donors and/or gametes,59,60,64 adolescents’ perspectives,65–67 children's reactions to learning they are donor conceived,68,69 and the views of donor-conceived adults.22,70–72 The literature on adoption was also appraised for additional insight,73–75 as was literature on child development76–78; family relationships, particularly surrounding disclosure and donor-conceived families79–83; and the larger body of literature about disclosing other types of sensitive information to children.84–86 As content was identified, written, and developed, we considered health literacy guidelines with the goal of keeping language simple, clear, and effective. 87

As we appraised the scientific literature, a gap emerged in that many studies examining disclosure among donor conception families were completed outside of the United States (US). This directly affects the contextual influences dimension of the DMP model. Moreover, the IPDAS Collaboration 25 and other experts in decision aid development 38 recommend the inclusion of parents who have direct experience making the decision that the decision aid is designed to affect. To provide content with details and insights from parents’ telling experiences, we completed research among US parents who used donated sperm, eggs, or embryos to conceive their children and who had talked with their children, ages 4 months to 16 years, about their genetic origins. 63 These findings were then incorporated into the TELL Tool content, primarily linked with the cognitive appraisal dimension because the findings provided insights, verbiage, nuances, and data about the decisions parents need to make regarding the who, what, when, and where within the telling process among US parents. 63

Incorporating clinicians’ views on parent needs into content. Insights from the investigative team's extensive research and clinical expertise, described elsewhere,5,75,88–92 were also incorporated into content for the TELL Tool. For example, Susan Klock, a leading psychologist in the infertility and third-party reproductive field and a member of the research team, prepared a short video that provides information on how partners in two-parent families can approach the issue of telling their children when the partners disagree or partially disagree about telling. The content for the video resulted both from evidence by Isaksson et al. that 24% of parents in two-parent families do not agree, only partially agree, or do not know the opinion of their partner regarding telling their children about their genetic origins 6 and from insights from Dr Klock's extensive clinical practice, in which she evaluates and addresses the psychological needs of donor-conceived recipient parents.

Determining the delivery format and distribution plan. While the five dimensions of the contemplate phase of the DMP model guided the content of the TELL Tool, Kolb's experiential learning theory 57 guided the delivery of the content and resulted in the four-module, multicomponent, interactive, multimedia (e.g. audio and video clips, visuals, and parent workbook) TELL Tool. The experiential learning theory includes four stages: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. 57 The learning process is introduced by a concrete experience, which calls for reflection and review (i.e. reflective observation); next, in abstract conceptualization, conclusions and assimilation of new information from a clearly well-structured presentation of ideas give rise to active experimentation—trying out what is learned. Within the TELL Tool, we actualized these four stages through, for example, (a) a concrete experience that centers the importance and challenges of telling children about their genetic origins; (b) reflective observations that include several vignettes (parent stories using audio and/or video clips) about how parents can manage their emotions about telling; and (c) an abstract conceptualization stage that provides parents with information in an interactive way to build confidence in telling. In (d) the active experimentation stage, parents create their own personalized TELL Plan and try out what they’ve learned. (See Table 1 for additional examples and mapping of content to theory.)

We opted for a digitally delivered decision aid because parents in our prior research and on the parents’ advisory board expressed interest in a readily accessible tool that could be completed in the privacy of their homes. This would obviate many logistical barriers to more traditional face-to-face delivery formats such as navigating work schedules and obtaining childcare.5,63 Meanwhile, clinicians on our team reported a need for high-quality, evidence-based decision support tools for parents to augment the education and counseling groundwork that takes place in the clinical setting. Our team's prior successes with the CHOICES web-based intervention among young adults45–47 and the ENGAGE-IL web-based platform of educational video modules,48,90 as well as emerging data from other digitally delivered parent interventions that show good promise for intervention efficacy and expanding the reach of parent support into the digital space, 93 were also considered.

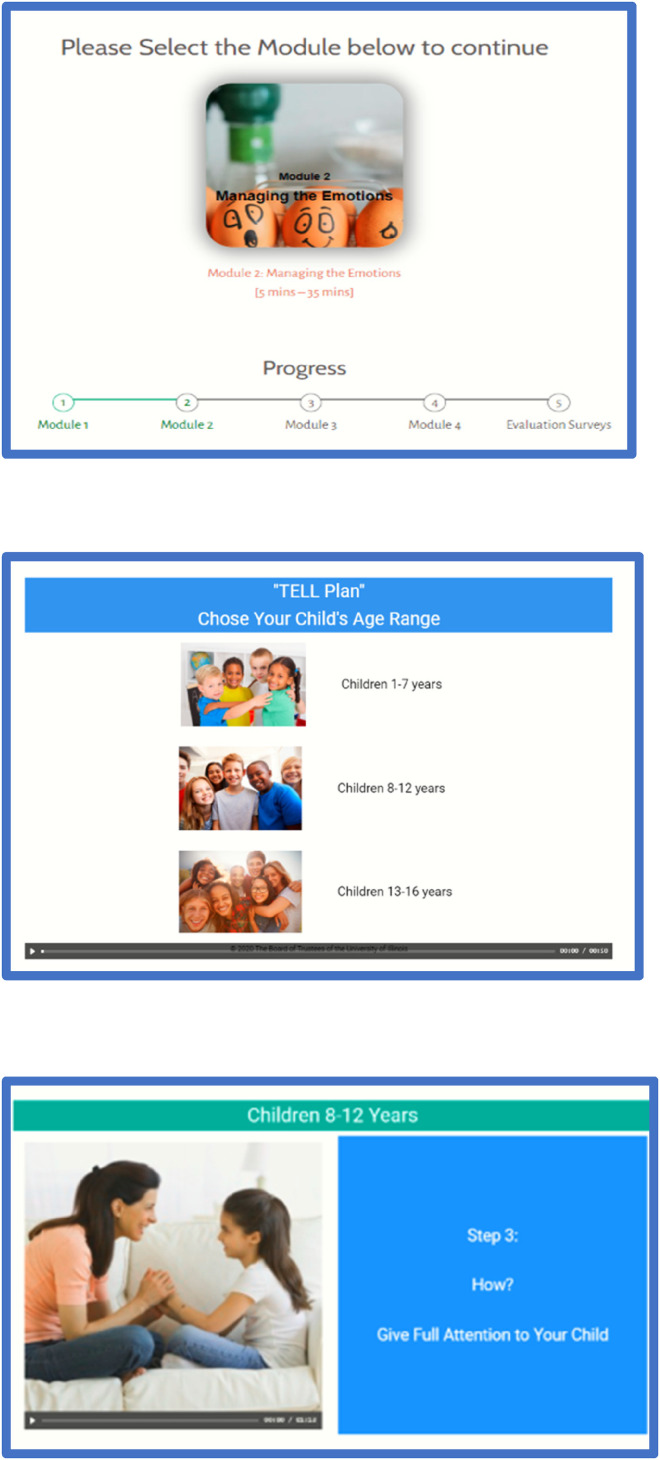

The delivery and distribution of the TELL Tool was completed in conjunction with a skilled technology team consisting of graduate students in computer science or computer engineering. With the investigative team and technology team working closely together, design elements were added to help parents navigate the digital program. These included a “progress” bar to visually show progression through the program and a screen icon clearly depicting the length of time needed for each of the audio or video components. Because confidentiality is of critical concern to many parents, the TELL Tool is delivered through a password-protected digital platform that meets all institutional review board approvals for the protection of human subjects.

Creating the early TELL Tool prototype

After completing the initial design work, and in keeping with IPDAS recommendations, we created an early and nimble prototype that underwent iterative changes following feedback from the investigative and technology teams’ ongoing meetings. An essential and early component of creating a decision aid is to develop storyboards (e.g. patient experiences, stories, and testimonies), 41 which we accomplished by creating several hypothetical parents and families. These parents and families represented diverse families by types of parental structures (e.g. single parents and coupled parents), gamete-donation families (e.g. egg, sperm, and embryo), donors (e.g. directed/identified and non-identified), parent's sexual orientation (heterosexual and same-sex), and children's ages, to align with our scope and target audience. Over 40 scripts were created to personify the various types of parents and families representing the target audience and then woven throughout the tool. As the storyboards and parent and family personas were created, we also strove to maintain diversity in culture, gender, race, and ethnicity. Regarding this latter point, we engaged over 35 volunteer undergraduate and graduate nursing students, from a variety of backgrounds and genders, including races and ethnicities known to be underrepresented or discriminated against in US health care settings (e.g. Blacks or African Americans and Hispanics), to serve as voice actors for the persona scripts.

As we envisioned how parent users would navigate the TELL Tool, we created four interactive and multimedia modules to deliver the content: (a) Understanding the Reasons, (b) Managing the Emotions, (c) Creating the TELL Plan, and (d) Selecting Specific Situations. We envisioned that parents would complete the TELL Tool in one session, or they could “suspend” the tool and return at a later point in time, ideally within 1 week. Giving parents control over their ability to navigate the content was a key design feature. Other examples of user control embedded in the design were to allow for parents’ personal needs. In Module 2: Managing the Emotions, for example, we created pre-set selection points where parents are instructed to select which of the 1 to 11 emotions discussed in the module are of interest to them personally. For instance, stigma and enduring grief are known barriers to disclosure. Thus, parents that select the emotions surrounding stigma or grief are provided with information and strategies to navigate each of these emotions. Parents then view the corresponding webpages that contain content for managing their selected emotions and not necessarily the entire content of the module.

Another key design element, developed by working closely with the technology team, is users’ ability to co-create a personalized TELL Plan in Module 3: Creating the TELL Plan. Each TELL Plan is co-created by parents and investigators: the parents, as they progress through the investigator-developed content within the module, are asked to make decisions at various “decision points” about how to tell their child(ren) about their genetic origins. After they complete the TELL Tool, their TELL Plan becomes an accessible resource, because it can be saved on their personal digital device for when they need to refer back to it.

Incorporating steering group review. Development of the prototype included iterative feedback from members of the larger steering group (e.g. parents’ advisory board and other stakeholders). Steering group members who were members of the parents’ or children's advisory boards met in groups or individually with members of the investigative team to provide feedback. Other steering group members provided feedback individually. This feedback was obtained verbally, and written summaries were kept to maintain the accuracy of the feedback. One key change made following feedback was to allow parents to select tailored information based on their children's age. This feedback resulted in the development of three age categories based on Piaget's stages of cognitive development 94 : children of 1–7 years, 8–12 years, and 13–16 years.

As content was created and redrafted, we continued to design elements such as the length of time (i.e. intervention “dose”) that parents would need to complete the TELL Tool. A length of 60 min was set as a target time frame for an individual parent to complete the entire tool in consideration of participant burden, insight from our prior intervention work, 46 and feedback from the steering group. We also opted for an audio-narration format that used images and short text on a visual screen versus providing extensive text for parents to read on the visual screens.

Finalizing the TELL Tool prototype. The final prototype of the TELL Tool, as prepared for alpha testing, consisted of 181 viewable screens across the 4 modules. Parents are not required to view all the screens, as children's ages and parents’ pre-set selections and responses to decision points exert some control over the order, level of detail, and type of content presented; this approach has been shown to increase the quality of user's decision-making. 95 Figure 3 shows examples of the TELL Tool screens used during alpha testing.

Figure 3.

Example screens from the TELL Tool prototype.

Discussion

To create the digital TELL Tool prototype, the investigative team used an inclusive, systematic, and iterative process guided by IPDAS Collaboration recommendations. The resulting decision aid for parents of children who were conceived through donated eggs, sperm, or embryos is comprehensive, theoretically driven, and evidence based. The digital format, which can be delivered to parents through the internet and mobile devices, provides a much needed, convenient, and readily accessible tool.

The design process documented here provides transparency about the early design steps employed to create and develop the TELL Tool prototype. Transparency about the developmental process can support the trustworthiness of a decision aid, which can in turn enable its implementation into clinical practice and/or the target community.25,96,97 Documentation of the participation—or lack thereof—of end users (i.e. parents who received donor gametes or embryos) and other stakeholders is also paramount to transparency and essential for establishing a high-quality decision aid. 97 For the TELL Tool, we engaged parents early in development through our parents’ advisory board. For example, members of the parents’ advisory board met during our formation and then twice during the year as the TELL Tool developed. They were also available for impromptu consultations (n = 4–5) throughout the year as needed. One member of the investigative team is also a gamete-recipient parent. Our stakeholders were integral to the early tool developmental process and actively participated at multiple steps. Moving beyond the IPDAS Collaboration's recommendations and aligning with the three pillars of design thinking, 42 we also established and engaged a donor-conceived children's advisory board. Members of this board allowed us to better understand children's perspectives about what is important in the telling process (empathy) and to actualize our work as an inclusive team (collaboration). Members of our children's advisory board met once prior to the development of the tool and due to considerations regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and school or other scheduling conflicts were available for individual consultations throughout the year (n = 2–3 individual consultations). Our report of the multiple categories where we examined, appraised, and synthesized a wide range of literature also adds to transparency.

A strength of our developmental process is the explicit use of two theoretical frameworks. The five dimensions of the DMP model guided the content for the TELL Tool, while Kolb's experiential learning theory 57 guided the delivery. The DMP model is an outgrowth of our investigative team's past research program, in which we sought to examine the underlying processes that influence parents’ decision-making about whether and, if so, how to talk with and tell children about their genetic origins. This model now provides a theoretical foundation for selecting content, where a grounding in theory is often missing from other reports of decision aid development. 98 This transparency is important because as future research unfolds, insight about the efficacy of the TELL Tool can be linked back to these theoretical models. These models can also inform the development of other decision tools—especially in the field of medical reproduction, which is what the DMP model is based on.

Another strength of our tool developmental process includes incorporating the extensive clinical expertise of the multidisciplinary investigative team along with health literacy guidelines, which are being increasingly recognized in decision aid development. 99 The length of time taken to create and develop the tool (∼1 year) is a testament to the care, quality, and attention to detail by the investigative team. Other investigators have also reported a prolonged and expensive, albeit necessary, process for developing a high-quality decision aid. 100

Limitations and future directions

We acknowledge several limitations to this study, including the impact of the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. When we created the TELL Tool, the evidence was unclear about how much information parents want or need and how much detail about disclosure is optimal, especially in a digital format. Our recently completed alpha test 36 and the beta test (i.e. field testing) that is now in progress will provide insights to address these concerns. Because the launch of our developmental study (January 2020) coincided with the emerging COVID-19 pandemic, our study was impacted by issues the investigators, students, and stakeholders experienced as economic shutdowns, public health emergencies, travel bans, stay-at-home bans, and other issues that accompanied the pandemic took hold. These issues limited the face-to-face meetings that took place and may have created limits as to what we could accomplish technologically.

Another limitation is that although we followed the IPDAS Collaboration's recommendations and used a systematic and rigorous developmental process, we still do not know whether the TELL tool is effective. Pending our beta test findings, the next phase in our program of research is to complete efficacy testing to determine whether the TELL Tool can aid parents’ decision-making processes and enable them to begin talking with and telling their children about their genetic origins. We also plan to investigate if the tool results in parents taking actionable steps in the telling process and if this improves the health and well-being of parents, children, and families.

Finally, the TELL Tool was designed specifically for parents who reside in the US, which limits generalizability. We do hope to implement future research to adapt the tool to align with contextual influences (e.g. the sociopolitical milieu and language) that affect parents’ decision-making processes regarding disclosure in other countries. Extending the tool for use with parents who have adult children who are unaware of their donor conception is another adaptation of the TELL Tool that we plan to explore.

Conclusions

To create and develop the TELL Tool prototype, our research team used an inclusive, systematic, and iterative process based on the IPDAS Collaboration recommendations. This process allowed us to develop a well-designed, theoretically driven, evidence-based digital decision aid for parents of children, ages 1 to 16 years, who were conceived through donated eggs, sperm, or embryos. The TELL Tool provides a much needed, convenient, and readily accessible tool to support these parents’ decision-making process by enabling them to begin talking with and telling their children about their genetic origins. Detailing our early developmental processes provides transparency that can benefit clinicians, researchers, and the donor-conceived community. Future research to determine the efficacy of the TELL Tool is planned, while additional research will also be needed to refine the tool for use on a global scale and with a broader scope of end users.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contributions of our technology team and of the members of our parents’ advisory board and children's advisory board. The authors thank Kyra Freestar of Bridge Creek Editing for providing editorial support in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines.

Footnotes

Contributorship: P.E.H. led the conception of the study; all authors made substantial contributions to the conception, design of the study, and the analysis. P.E.H. and A.M.G. prepared the first draft of the manuscript, and all other authors revised it critically for intellectual content; all authors read and approved the final version for publication.

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. P.E.H. reports honoraria from the Midwest Reproductive Symposium International for her presentation in June 2022 and is the Immediate Past-Chair of the Nurses Professional Group Executive Board, American Society for Reproductive Medicine. The TELL Tool prototype is copyrighted by the Regents of the University of Michigan and the University of Illinois Board of Trustees, University of Illinois Chicago Invention Identification Number UIC-2020-151. The authors receive no monetary compensation for use of the tool.

Ethical approval: Members of the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at the University of Illinois Chicago (Protocol # 2020-1086) and the University of Michigan (Protocol #HUM00230985) approved this study.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The project described was supported by an Association of Women's Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN) Every Woman, Every Baby research grant award and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing research grant award No. R34NR0192781. The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of AWHONN or the National Institutes of Health.

Guarantor: PEH.

ORCID iD: Patricia E. Hershberger https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6598-6374

References

- 1.Barton M, Walker K, Wiesner BP. Artificial insemination. Br Med J 1945; 1: 40–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frith L. Gamete donation and anonymity: the ethical and legal debate. Hum Reprod 2001; 16: 818–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tallandini MA, Zanchettin L, Gronchi G, et al. Parental disclosure of assisted reproductive technology (ART) conception to their children: a systematic and meta-analytic review. Hum Reprod 2016; 31: 1275–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Applegarth LD, Kaufman NL, Josephs-Sohan M, et al. Parental disclosure to offspring created with oocyte donation: intentions versus reality. Hum Reprod 2016; 31: 1809–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hershberger PE, Driessnack M, Kavanaugh K, et al. Oocyte donation disclosure decisions: a longitudinal follow-up at middle childhood. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2021; 24: 31–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isaksson S, Sydsjö G, Skoog Svanberg A, et al. Disclosure behaviour and intentions among 111 couples following treatment with oocytes or sperm from identity-release donors: follow-up at offspring age 1–4 years. Hum Reprod 2012; 27: 2998–3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacCallum F, Keeley S. Disclosure patterns of embryo donation mothers compared with adoption and IVF. Reprod Biomed Online 2012; 24: 745–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Visser M, Kop PA, van Wely M, et al. Counselling on disclosure of gamete donation to donor offspring: a search for facts. Facts Views Vis Obgyn 2012; 4: 159–172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ESHRE Working Group on Reproductive Donation, Kirkman-Brown J, Calhaz-Jorge C, et al. Good practice recommendations for information provision for those involved in reproductive donation. Hum Reprod Open 2022; 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Informing offspring of their conception by gamete or embryo donation: an Ethics Committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2018; 109: 601–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Health and Medical Research Council. Ethical guidelines on the use of assisted reproductive technology in clinical practice and research . Canberra: Australian Government, National Health and Medical Research Council, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harper JC, Kennett D, Reisel D. The end of donor anonymity: how genetic testing is likely to drive anonymous gamete donation out of business. Hum Reprod 2016; 31: 1135–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klotz M. Wayward relations: novel searches of the donor-conceived for genetic kinship. Med Anthropol 2016; 35: 45–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGovern PG, Schlaff WD. Sperm donor anonymity: a concept rendered obsolete by modern technology. Fertil Steril 2018; 109: 230–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pasch LA. New realities for the practice of egg donation: a family-building perspective. Fertil Steril 2018; 110: 1194–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braverman AM. Mental health counseling in third-party reproduction in the United States: evaluation, psychoeducation, or ethical gatekeeping? Fertil Steril 2015; 104: 501–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crawshaw M, Daniels K. Revisiting the use of ‘counselling’ as a means of preparing prospective parents to meet the emerging psychosocial needs of families that have used gamete donation. Fam Relatsh Soc 2019; 8: 395–409. [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Human Genome Research Institute. Talking glossary of genomic and genetic terms, https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary (2022, accessed 29 August 2022).

- 19.Wildin RS, Messersmith DJ, Houwink EJF. Modernizing family health history: achievable strategies to reduce implementation gaps. J Community Genet 2021; 12: 493–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu MR, Kurnat-Thoma E, Starkweather A, et al. Precision health: a nursing perspective. Int J Nurs Sci 2020; 7: 5–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanghavi K, Moses I, Moses D, et al. Family health history and genetic services-the East Baltimore community stakeholder interview project. J Community Genet 2019; 10: 219–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frith L, Blyth E, Crawshaw M, et al. Secrets and disclosure in donor conception. Sociol Health Ill 2018; 40: 188–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Indekeu A, Maas AJBM, McCormick E, et al. Factors associated with searching for people related through donor conception among donor-conceived people, parents, and donors: a systematic review. F&S Reviews 2021; 2: 93–119. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 4: CD001431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sepucha KR, Abhyankar P, Hoffman AS, et al. Standards for UNiversal reporting of patient Decision Aid Evaluation studies: the development of SUNDAE checklist. BMJ Qual Saf 2018; 27: 380–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manteghinejad A, Javanmard SH. Challenges and opportunities of digital health in a post-COVID19 world. J Res Med Sci 2021; 26: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. WHO guideline: recommendations of digital interventions for health system strengthening, https: //www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550505 (2019, accessed 29 August 2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meskó B, Drobni Z, Bényei É, et al. Digital health is a cultural transformation of traditional healthcare. Mhealth 2017; 3: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez-Olivo MA, Suarez-Almazor ME. Digital patient education and decision aids. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2019; 45: 245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ren W, Huang C, Liu Y, et al. The application of digital technology in community health education. Digit Med 2015; 1: 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donor Conception Network. Parent led: child focused. Supporting donor conception families for 30 years, https://www.dcnetwork.org/ (2022, accessed 29 August 2022).

- 32.Johnson L, Bourne K, Hammarberg K. Donor conception legislation in Victoria, Australia: the “Time to Tell” campaign, donor-linking and implications for clinical practice. J Law Med 2012; 19: 803–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Victorian Assisted Reproductive Treatment Authority, Department of Health and State Government of Victoria . Time to tell video series, https://www.varta.org.au/events-support-groups/time-tell-video-series (2020, accessed 29 August 2022).

- 34.Gatlin M, LieberWilkins C. Let’s talk about egg donation: real stories from real people . Bloomington, IN: Archway, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Family Equality Council. National network of LGBTQ family groups, https://www.familyequality.org/family-support/national-network-lgbtq-family-groups/ (2022, accessed 28 December 2022).

- 36.Hershberger PE, Gallo AM, Adlam K, et al. Alpha test of the donor conception tool to empower parental telling and talking. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2022; 51: 536–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoffman AS, Sepucha KR, Abhyankar P, et al. Explanation and elaboration of the Standards for UNiversal reporting of patient Decision Aid Evaluations (SUNDAE) guidelines: examples of reporting SUNDAE items from patient decision aid evaluation literature. BMJ Qual Saf 2018; 27: 389–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elwyn G, Kreuwel I, Durand MA, et al. How to develop web-based decision support interventions for patients: a process map. Patient Educ Couns 2011; 82: 260–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jandoo T. WHO Guidance for digital health: what it means for researchers. Digit Health 2020; 6: 2055207619898984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Quality Forum. National standards for the certification of patient decision aids . Washington, DC: National Quality Forum, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coulter A, Stilwell D, Kryworuchko J, et al. A systematic development process for patient decision aids. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013; 13: S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferreira FK, Song EH, Gomes H, et al. New mindset in scientific method in the health field: design thinking. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2015; 70: 770–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dirksen J. Design for how people learn. 2nd ed. Indianapolis, IN: New Riders, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dirksen J. Design for motivation. In: Dirksen J. (eds) Design for how people learn. 2nd ed. Indianapolis, IN: New Riders, 2016, pp.215–228. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gallo AM, Wilkie DJ, Wang E, et al. Evaluation of the SCKnowIQ tool and reproductive CHOICES intervention among young adults with sickle cell disease or sickle cell trait. Clin Nurs Res 2014; 23: 421–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gallo AM, Wilkie DJ, Yao Y, et al. Reproductive health CHOICES for young adults with sickle cell disease or trait: randomized controlled trial outcomes over two years. J Genet Counsel 2016; 25: 325–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilkie DJ, Gallo AM, Yao Y, et al. Reproductive health choices for young adults with sickle cell disease or trait: randomized controlled trial immediate posttest effects. Nurs Res 2013; 62: 352–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.ENGAGE-IL. Interprofessional continuing education, https://engageil.com (2017, accessed 29 August 2022).

- 49.Hadizadeh-Talasaz F, Simbar M, Latifnejad Roudsari R. Exploring infertile couples’ decisions to disclose donor conception to the future child. Int J Fertil Steril 2020; 14: 240–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hertz R, Nelson MK. Acceptance and disclosure: comparing genetic symmetry and genetic asymmetry in heterosexual couples between egg recipients and embryo recipients. Facts Views Vis Obgyn 2016; 8: 11–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bracewell-Milnes T, Saso S, Bora S, et al. Investigating psychosocial attitudes, motivations and experiences of oocyte donors, recipients and egg sharers: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update 2016; 22: 450–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Indekeu A, Dierickx K, Schotsmans P, et al. Factors contributing to parental decision-making in disclosing donor conception: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update 2013; 19: 714–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hershberger PE, Gallo AM, Kavanaugh K, et al. The decision-making process of genetically at-risk couples considering preimplantation genetic diagnosis: initial findings from a grounded theory study. Soc Sci Med 2012; 74: 1536–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hershberger PE, Pierce PF. Conceptualizing couples’ decision making in PGD: emerging cognitive, emotional, and moral dimensions. Patient Educ Couns 2010; 81: 53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hershberger PE, Finnegan L, Altfeld S, et al. Toward theoretical understanding of the fertility preservation decision-making process: examining information processing among young women with cancer. Res Theory Nurs Pract 2013; 27: 257–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hershberger PE, Sipsma H, Finnegan L, et al. Reasons why young women accept or decline fertility preservation after cancer diagnosis. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2016; 45: 123–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kolb DA, Boyatzis RE, Mainemelis C. Experiential learning theory: previous research and new directions. In: Sternberg RJ, Zhang LF. (eds) Perspectives on thinking, learning, and cognitive styles. New York: Routledge, 2011, pp.227–248. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hershberger P. Recipients of oocyte donation: an integrative review. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2004; 33: 610–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mac Dougall K, Becker G, Scheib JE, et al. Strategies for disclosure: how parents approach telling their children that they were conceived with donor gametes. Fertil Steril 2007; 87: 524–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blake L, Casey P, Readings J, et al. ‘Daddy ran out of tadpoles’: how parents tell their children that they are donor conceived, and what their 7-year-olds understand. Hum Reprod 2010; 25: 2527–2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rumball A, Adair V. Telling the story: parents’ scripts for donor offspring. Hum Reprod 1999; 14: 1392–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harper JC, Abdul I, Barnsley N, et al. Telling donor-conceived children about their conception: evaluation of the use of the Donor Conception Network children’s books. Reprod Biomed Soc Online 2022; 14: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hershberger PE, Gallo AM, Adlam K, et al. Parents’ experiences telling children conceived by gamete and embryo donation about their genetic origins. F S Rep 2021; 2: 479–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Provoost V, Bernaerdt J, Van Parys H, et al. ‘No daddy’, ‘a kind of daddy’: words used by donor conceived children and (aspiring) parents to refer to the sperm donor. Cult Health Sex 2018; 20: 381–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jadva V, Freeman T, Kramer W, et al. The experiences of adolescents and adults conceived by sperm donation: comparisons by age of disclosure and family type. Hum Reprod 2009; 24: 1909–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Scheib JE, Riordan M, Rubin S. Adolescents with open-identity sperm donors: reports from 12–17 year olds. Hum Reprod 2005; 20: 239–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zadeh S, Ilioi EC, Jadva V, et al. The perspectives of adolescents conceived using surrogacy, egg or sperm donation. Hum Reprod 2018; 33: 1099–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Blake L, Casey P, Jadva V, et al. ‘I was quite amazed’: donor conception and parent–child relationships from the child’s perspective. Child Soc 2014; 28: 425–437. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Isaksson S, Skoog-Svanberg A, Sydsjö G, et al. It takes two to tango: information-sharing with offspring among heterosexual parents following identity-release sperm donation. Hum Reprod 2016; 31: 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Blyth E, Crawshaw M, Frith L, et al. Donor-conceived people’s views and experiences of their genetic origins: a critical analysis of the research evidence. J Law Med 2012; 19: 769–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lozano EB, Fraley RC, Kramer W. Attachment in donor-conceived adults: curiosity, search, and contact. Pers Relatsh 2019; 26: 331–344. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scheib JE, McCormick E, Benward J, et al. Finding people like me: contact among young adults who share an open-identity sperm donor. Hum Reprod Open 2020; 4: hoaa057. Published correction appears in Hum Reprod Open 2021; 1: hoaa069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brodzinsky DM. Children’s understanding of adoption: developmental and clinical implications. Prof Psychol Res Pr 2011; 42: 200–207. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grotevant HD, Wrobel GM, Fiorenzo L, et al. Trajectories of birth family contact in domestic adoptions. J Fam Psychol 2019; 33: 54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grotevant HD, Lo AY. Adoptive parenting. Curr Opin Psychol 2017; 15: 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Barten SS. How does the child know? Origins of the symbol in the theories of Piaget and Werner. J Am Acad Psychoanal 1980; 8: 77–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bibace R, Walsh ME. Development of children’s concepts of illness. Pediatrics 1980; 66: 912–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Davies D, Troy MF. Child development: a practitioner’s guide. 4th ed. New York: The Guilford Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Golombok S, Readings J, Blake L, et al. Children conceived by gamete donation: psychological adjustment and mother-child relationships at age 7. J Fam Psychol 2011; 25: 230–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Golombok S, Blake L, Casey P, et al. Children born through reproductive donation: a longitudinal study of psychological adjustment. J Child Psychol Psychiartry 2013; 54: 653–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ilioi E, Blake L, Jadva V, et al. The role of age of disclosure of biological origins in the psychological wellbeing of adolescents conceived by reproductive donation: a longitudinal study from age 1 to age 14. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2017; 58: 315–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Slutsky J, Jadva V, Freeman T, et al. Integrating donor conception into identity development: adolescents in fatherless families. Fertil Steril 2016; 106: 202–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Widbom A, Isaksson S, Sydsjo G, et al. Positioning the donor in a new landscape-mothers’ and fathers’ experiences as their adult children obtained information about the identity-release sperm donor. Hum Reprod 2021; 36: 2181–2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Molokwane M, Madiba S. Truth, deception, and coercion; communication strategies used by caregivers of children with perinatally acquired HIV during the pre-disclosure and post-disclosure period in rural communities in South Africa. Glob Pediatr Health 2021; 8: 2333794X211022269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Peipins LA, Rodriguez JL, Hawkins NA, et al. Communicating with daughters about familial risk of breast cancer: individual, family, and provider influences on women’s knowledge of cancer risk. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2018; 27: 630–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rosenberg AR, Starks H, Unguru Y, et al. Truth telling in the setting of cultural differences and incurable pediatric illness: a review. JAMA Pediatr 2017; 171: 1113–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Toolkit for making written material clear and effective, https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Outreach/WrittenMaterialsToolkit (2021, accessed 29 August 2022). [PubMed]

- 88.Driessnack M. Children’s drawings as facilitators of communication: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Nurs 2005; 20: 415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gallo AM, Angst DB, Knafl KA. Disclosure of genetic information within families. Am J Nurs 2009; 109: 65–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gruss V, Hasnain M. A smartphone application for educating the public about Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Gerontechnology 2020; 19: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hershberger PE, Klock SC, Barnes RB. Disclosure decisions among pregnant women who received donor oocytes: a phenomenological study. Fertil Steril 2007; 87: 288–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pasch LA, Benward J, Scheib JE, et al. Donor-conceived children: the view ahead. Hum Reprod 2017; 32: 1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Breitenstein SM, Gross D, Christophersen R. Digital delivery methods of parenting training interventions: a systematic review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2014; 11: 168–176. Published correction appears in Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2015; 12: 249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Scott HK, Cogburn M. Piaget. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448206/ [Google Scholar]

- 95.Syrowatka A, Krömker D, Meguerditchian AN, et al. Features of computer-based decision aids: systematic review, thematic synthesis, and meta-analyses. J Med Internet Res 2016; 18: e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Elwyn G, Scholl I, Tietbohl C, et al. “Many miles to go …”: a systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013; 13: S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Witteman HO, Maki KG, Vaisson G, et al. Systematic development of patient decision aids: an update from the IPDAS Collaboration. Med Decis Mak 2021; 41: 736–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Durand MA, Stiel M, Boivin J, et al. Where is the theory? Evaluating the theoretical frameworks described in decision support technologies. Patient Educ Couns 2008; 71: 125–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Muscat DM, Smith J, Mac O, et al. Addressing health literacy in patient decision aids: an update from the International Patient Decision Aid Standards. Med Decis Making 2021; 41: 848–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Savelberg W, van der Weijden T, Boersma L, et al. Developing a patient decision aid for the treatment of women with early stage breast cancer: the struggle between simplicity and complexity. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2017; 17: 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]