Abstract

Background:

Augmentation with subacromial bursa has not been fully established in bursal-sided partial-thickness rotator cuff tears (PT-RCTs).

Purpose:

To compare the results of acromioplasty + arthroscopic debridement versus acromioplasty + augmentation with subacromial bursa for Ellman type 2 PT-RCTs involving 25% to 50% of the tendon surface area.

Study Design:

Cohort study; Level of evidence, 3.

Methods:

Included were 40 patients (mean age, 47.8 years) with Ellman type 2 PT-RCTs whose symptoms did not regress despite 3 months of nonoperative treatment. The patients underwent either acromioplasty + debridement (group A; n = 18) or acromioplasty + augmentation (group B; n = 22). Outcome scores (visual analog scale [VAS] pain score, Constant-Murley score [CMS], and American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [ASES] score) were obtained preoperatively and at 6, 12, and 18 months postoperatively. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans performed at 6 months postoperatively were used to determine the integrity and state of healing.

Results:

There were no significant differences between groups A and B in preoperative VAS, CMS, or ASES scores, and patients in both groups saw significant improvement at each follow-up time point on all 3 outcome scores (P = .001 for all). Scores on all 3 outcome measures were significantly better in group B than group A at each postoperative time point (P < .05 for all). Postoperative MRI scans revealed persistent partial tears in 5 of 18 patients in group A compared with 2 of 22 patients in group B (P < .05). Conversion to full-thickness tear (3/18 patients) was seen only in group A.

Conclusion:

Patients who underwent biological augmentation of their PT-RCTs had improved outcome scores compared with those treated with acromioplasty and debridement alone.

Keywords: partial thickness, bursal side, rotator cuff, full thickness, subacromial bursa

The incidence of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears (PT-RCTs; 13%-32%) is higher than that of full-thickness rotator cuff tears (FT-RCTs) 21 and may be the cause of unexplained shoulder pain. 9,10 PT-RCTs, which are classified arthroscopically according to localization and the depth of the tear, 7 can be on the articular surface, on the bursal face, or intratendinous. Bursal-sided tears are thought to be caused by subacromial impingement 26 and are more painful than articular-sided tears. 9 Bursal- or articular-sided tears with a depth <3 mm are classified as grade 1, tears with a depth of 3 to 6 mm as grade 2, and tears with a depth >6 mm (>50% of tendon thickness) as grade 3. 7 Since acromioplasty or arthroscopic debridement treatments fail in high-grade tears in 50% of the patients, 23 repair methods such as transtendon repair, tear completion and repair, and transosseous repair give better results. 13 Nonoperative treatment is more prominent in grade 1 tears. 13 There is controversy regarding the management of Ellman grade 2 tears that are 25% to 50% of the tendon thickness. 26

Histopathological studies of PT-RCTs have revealed limited potential for spontaneous healing, and the proximal stump of the rotator cuff is rounded, retracted, and avascular. 24 Several authors have proposed improving the healing of PT-RCTs using augmentation with subacromial bursa, which has been shown to have biological potential. 1,3,7,18 Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent progenitor cells whose main source is the bone marrow. They have the potential to differentiate into mature cells of mesenchymal tissues (eg, osteocytes, tenocytes, chondrocytes, and adipocytes). MSCs, which can be found in many other tissues, such as adipose tissue, are thought to actually originate in blood vessel walls. 4 The subacromial bursa is a well-vascularized anatomic structure with a blood vessel density of 1.8% to 3.4%. The caudal part of the subacromial bursa and the bursal surfaces of the rotator cuff tendons have the same dense arterial support. 18 The presence of such a dense vascular structure of the subacromial bursa causes it to host a large number of MSCs. 11,14,17,19 Considering this potential, good results have been reported in studies in which biological augmentation using subacromial bursa was performed. 1,8,16

The aim of our study was to compare the efficacy of acromioplasty + arthroscopic debridement versus acromioplasty + augmentation with subacromial bursa for bursal-sided Ellman grade 2 PT-RCTs. We hypothesized that biological augmentation with the subacromial bursa would yield superior clinical results.

Methods

This was a retrospective review of prospectively collected data from a single center that was conducted between January 2019 and February 2021. Included were patients with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evidence of partial-thickness supraspinatus tears that failed to respond to nonoperative treatment (3 months of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and physical therapy). Exclusion criteria were patients with major shoulder pathologies such as frozen shoulder, symptomatic biceps tendinitis, or Bankart lesion diagnosed during arthroscopic examination; articular-sided, intratendinous, or FT-RCTs; previous shoulder surgery; and injection history. Patients for whom the tendon could not be covered with a bursa for various reasons underwent acromioplasty and debridement alone (group A) and composed the control group. The remaining patients underwent acromioplasty and augmentation (group B). This study was performed according to the ethical standards in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The study protocol received institutional review board approval, and all included patients provided written informed consent.

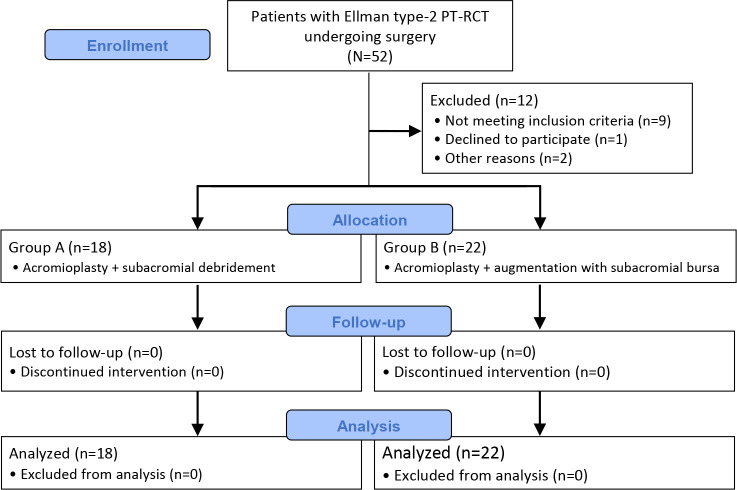

A total of 52 patients with Ellman type 2 PT-RCT underwent surgery. Of these patients, 12 were excluded: 9 patients did not meet the inclusion criteria, 1 did not come to regular follow-ups, 1 had an articular cartilage lesion that was detected during arthroscopic surgery, and 1 had a subscapularis tear. Thus, 40 patients were included in the study: 18 patients in group A (acromioplasty + debridement) and 22 patients in group B (acromioplasty + augmentation) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patient inclusion. PT-RCT, partial-thickness rotator cuff tear.

Surgical Technique

All surgeries were performed by the same shoulder surgeon (S.S.D.) with the patient in the beach-chair position under general anesthesia. After the standard posterior and anterior portals were opened, diagnostic arthroscopy was performed. The biceps tendon was examined with a probe to determine tendon mobility and determine fraying, detachment, or bucket-handle tearing of the superior labrum. Evaluation was made for a Bankart lesion or posterior capsular tension that may have been overlooked. The coracohumeral ligament, supraspinatus, and subscapularis tendons were evaluated intra-articularly for any pathology. None of the patients with shoulder pathology other than PT-RCT were included in the study.

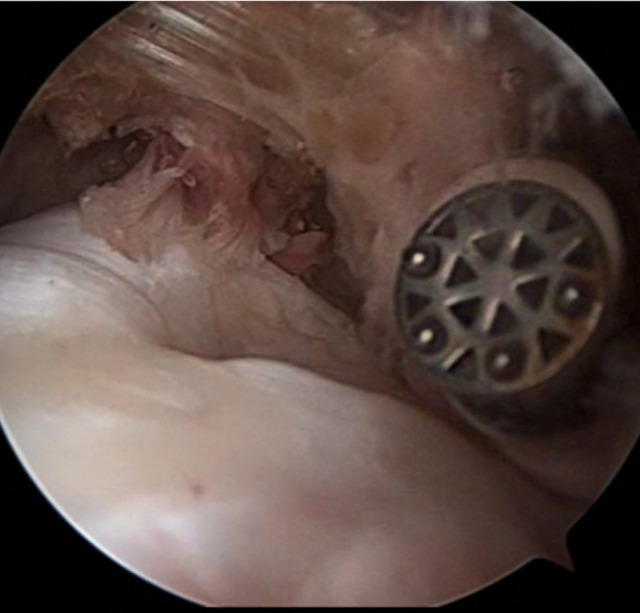

The arthroscope was directed to the subacromial area and the bursal-sided tear was observed (Figure 2). The size, location, and depth of the tear were recorded. After confirming that the patient had an Ellman grade 2 tear, 1 of the 2 treatments was applied.

Figure 2.

Posterolateral viewing portal showing the bursal tissue (*) and partial-thickness rotator cuff tear (**). The probe (X) was introduced from the anterior portal.

Subacromial decompression was performed in both groups of patients included in this study. Formal acromioplasty was applied to form a type 1 flat acromion in all patients. In group A patients, degenerated tendons and soft tissues of the bursa on the tear surface were debrided until intact tendon fibers on the articular surface. Bursectomy was performed and the surgery was terminated.

No debridement of the partial tear was performed in group B patients. The subacromial bursa was harvested after acromioplasty in group B patients. Subacromial bursa was harvested for augmentation via the lateral portal with the help of a radiofrequency device (Figure 3). Dissection was performed medially to posterolaterally; it was continued until the adherence of bursal tissue to the deltoid fascia was seen laterally. Since vascular support of the bursal layer is provided by suprascapular vessels in the medial region and deltoid vessels in the posterior and lateral regions, care was taken to maintain the bursal continuity in the medial and lateral areas during the harvesting. 2 Harvesting was continued until enough bursal tissue was mobilized as a single structure to cover the debrided supraspinatus area.

Figure 3.

Posterolateral viewing portal showing subacromial bursa harvesting with the help of a radiofrequency device introduced from the anterior portal.

An intact and mobile vascular bursa layer of appropriate thickness could not be obtained in all patients to augment. Harvested bursa was fixed with a No. 2 nonabsorbable ultra–high-molecular-weight polyethylene suture (MaxBraid; Zimmer Biomet) that was carried through the lasso by a carrier suture (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Arthroscopic images from the lateral viewing portal. (A) Passing the carrier suture through the bursa and (B) taking the carrier suture passed through the bursa with a grasper device (device from anterolateral portal). (C) Carrier suture passed through the bursa (*). (D) High-strength suture passing through the bursa (suture from anterolateral portal).

After fixation, the high-strength suture was placed to the lateral side of the footprint with a knotless anchor (Quattro Link Knotless Anchors; Zimmer Biomet), so the bursa was augmented on the partial rotator cuff tear (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

(A) High-strength suture that fixes bursa is loaded to knotless anchor. (B) Placing the anchor on which the high-strength suture is loaded. (C) Appearance of bursal-sided partial rotator cuff tear after covered with a bursa (*). Lateral viewing portal, anchor from anterolateral portal.

Rehabilitation

All patients used a shoulder-arm sling for 6 weeks postoperatively, with the shoulder in 15° of abduction and neutral rotation. An ice bag was used to reduce edema and pain on the first postoperative day. Gentle pendulum exercises were started at postoperative week 3. In the third postoperative week, passive external rotation and passive range of motion movements were started. Active assisted movements were started after 6 weeks postoperatively.

Outcome Evaluation

The visual analog scale (VAS) pain score, Constant-Murley score (CMS), and American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score for functional outcomes were used to evaluate the clinical outcomes. Preoperative and 6-, 12-, and 18-month postoperative scores were retrieved from medical records to compare statistically.

All patients in both groups underwent MRI (Gyroscan Powertrak 3000) preoperatively and at 6 months postoperatively. Oblique coronal, oblique sagittal, and transverse T2-weighted sequences were used. The supraspinatus tendon status was evaluated according to the magnetic resonance–based assessment system of Sugaya et al 20 by 2 shoulder surgeons (S.S.D. and Y.I.) with at least 10 years of experience who were blinded to the treatment type. According to this classification, type 1 defines repaired cuffs of low intensity but with sufficient thickness compared with the normal cuff, type 2 describes partial high-intensity area cuffs that have sufficient thickness compared with the normal cuff, type 3 describes PT-RCTs without discontinuity, type 4 describes small FT-RCTs, and type 5 describes large FT-RCTs.

Statistical Analysis

The study sample size was calculated with the G*Power 3.1.9.4 program (Franz Faul), taking into account the significance level and effect size of the established hypothesis. A study by Muench et al 16 calculated the mean preoperative (45.8 ± 22.5) and postoperative (88.5 ± 14.6) ASES scores with an effect size of 1.95 (high effect level). In order to find a significant difference between the groups while α = .05 and 1 – β = 0.95 (ie, the error amount was .005 and the power of the test was 95%), the minimum sample size needed was calculated as 10 people in each group.

The IBM SPSS Statistics 22 program (IBM Corp) was used for statistical analyses. The conformity of the parameters to the normal distribution was evaluated by the Shapiro-Wilk test. For comparison of quantitative data between groups A and B, the Student t test was used for parameters with normal distribution, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for parameters with nonnormal distribution. Repeated-measures analysis of variance was used for within-group comparisons of normally distributed parameters, and the Bonferroni test was used for post hoc pairwise comparisons. The Friedman test was used for intragroup comparisons of parameters, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for post hoc pairwise comparisons. Significance was set at P < .05.

Results

The mean age of the 18 study patients was 47.8 years in group A and 22 study patients was 46.4 in group B. The characteristics of the patients according to study group are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Groups

| Group A (Acromioplasty + Debridement) | Group B (Acromioplasty + Augmentation) | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 18 | 22 |

| Sex, female/male, n | 10/8 | 12/10 |

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 47.8 ± 12.4 | 46.4 ± 13.1 |

| Dominant side affected, n | 14 | 16 |

Clinical Outcome Scores

There was no statistically significant difference between groups A and B in the preoperative VAS pain score, CMS, or ASES score, and patients in both groups saw significant changes from preoperatively to 6, 12, and 18 months postoperatively on all 3 outcome measures (P = .001 for all) (Table 2). At 6, 12, and 18 months postoperatively, the VAS pain score, CMS, and ASES score in group B were significantly better than those in group A (P < .05 for all) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of Outcome Scores Between Groups and Over Time a

| Group A (Acromioplasty + Debridement) | Group B (Acromioplasty + Augmentation) | Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAS pain score | |||

| Preop | 5.44 ± 1.34 (5) | 5.68 ± 1.21 (6) | .476 |

| 6 mo postop | 3.11 ± 0.83 (3) | 2.45 ± 0.67 (2) | .013 |

| 12 mo postop | 2.39 ± 0.61 (2) | 1.64 ± 0.73 (2) | .001 |

| 18 mo postop | 1.33 ± 0.77 (1.5) | 0.73 ± 0.55 (1) | .008 |

| Pc | .001 | .001 | |

| CMS | |||

| Preop | 46.50 ± 7.00 | 43.82 ± 4.91 | .163 |

| 6 mo postop | 62.39 ± 5.75 | 69.36 ± 5.03 | .001 |

| 12 mo postop | 76.50 ± 4.40 | 85.18 ± 3.51 | .001 |

| 18 mo postop | 86.00 ± 3.66 | 91.68 ± 2.75 | .001 |

| Pc | .001 | .001 | |

| ASES score | |||

| Preop | 33.61 ± 4.59 | 33.36 ± 4.28 | .861 |

| 6 mo postop | 69.94 ± 5.15 | 75.45 ± 6.36 | .005 |

| 12 mo postop | 79.83 ± 2.18 | 86.09 ± 3.34 | .001 |

| 18 mo postop | 88.83 ± 2.04 | 92.64 ± 2.59 | .001 |

| P c | .001 | .001 |

a Data are presented as mean ± SD (median). Boldface P values indicate a statistically significant difference between groups or time points (P < .05). ASES, American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons; CMS, Constant-Murley score; postop, postoperatively; Preop, preoperatively; VAS, visual analog scale.

b Mann-Whitney U test for VAS pain; Student t test for CMS and ASES.

c Friedman test for VAS pain; repeated-measures analysis of variance for CMS and ASES.

Supraspinatus Tendon Status on MRI

On 6-month postoperative MRI, the tendon status in group A was Sugaya type 1 (normal thickness and low signal intensity) in 7 patients, type 2 (normal thickness and high signal intensity) in 3 patients, type 3 (partial-thickness tear) in 5 patients, and type 4 (small complete tear) in 3 patients. In group B, the tendon status was type 1 in 15 patients, type 2 in 5 patients, and type 3 in 2 patients. Persistent partial tears were seen in significantly more patients in group A than in group B (5/18 vs 2/22, respectively; P < .05, Fisher exact test). Conversion to full-thickness tear was seen only in group A (3/18 patients).

Discussion

This is the first study in the literature to compare the effectiveness of these 2 treatment types for PT-RCTs. The main finding of this study was that the postoperative outcome scores and MRI findings were superior in group B (acromioplasty + augmentation) compared with group A (acromioplasty + debridement) (P < .05 for all). Thus, our hypothesis was confirmed.

Discussions about whether the subacromial bursa is the cause of shoulder pathologies or the source of the regeneration ability of the shoulder still continue. 11,12 According to the authors who claim that the subacromial bursa is deleterious, the bursa is in close relationship with the rotator cuff tendons it covers, and the pathological changes like villus formation, inflammation, and bursal adhesion cause changes in the rotator cuff muscles as well. 11

Studies on biological augmentation using subacromial bursa in arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs started to increase after it was determined that bursal tissue is a source of MSCs. 11,17,19 Studies on the biological quality of MSCs obtained from the subacromial bursa have yielded very conspicuous results. In their histological studies comparing cells taken from synovium, subacromial bursa, supraspinatus tendon, and enthesis, Utsunomiya et al 22 found that subacromial bursa and synovium were superior to other regions in terms of cell viability, colony number per nucleated cell, proliferative ability, and adipogenic and osteogenic ability. In the context of this study, the mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) extracted from the subacromial bursa exhibited greater differentiation capacity and gene expression potential compared to the MSCs obtained by arthroscopic aspiration of bone marrow from the proximal humerus. 6,15

There is lack of consensus about whether arthroscopic debridement or repair is the best treatment option for Ellman grade 2 tears. Since the mechanism of bursal-sided tears is thought to be due to subacromial impingement, acromioplasty is performed generally for the treatment. 26 The presence of type 2 or 3 acromion in preoperative planning in >80% of the patients and symptoms related to impingement or subacromial bursitis in physical examination indicate that acromioplasty treatment is appropriate. 25 In the present study, acromioplasty was performed in both patient groups, in line with this information.

The issue that cannot be agreed on is whether arthroscopic debridement with acromioplasty or repairing the tear by converting it to a full-thickness tear should be preferred. While there are publications recommending the repair of tears >25% of the tendon thickness, there are also publications reporting that debridement yields good results in tears with a tendon thickness of <50%. 3,5,26 The results of the studies using only subacromial bursa, subacromial bursa + bone marrow aspirate + platelet-rich plasma as a biological augmentation material, or a composite repair material consisting of biceps + cuff + bursa are quite satisfactory. 1,8,16

In our study, the bursal tissue of patients who underwent bursal augmentation was mobilized as a continuous layer (vascular bursal quilt) by preserving the medial and lateral vascularity of the subacromial bursa, as defined by Bhatia et al. 2 In an another study involving bursal augmentation, the bursa was secured to the tendon using the side-to-side suture technique. 11 However, our findings indicate that if the bursa is adequately mobilized, it can be affixed to the lateral aspect of the footprint using an anchor to address partial tendon tears. In a study investigating the effects of biological adjuvants, including the subacromial bursa, on rotator cuff healing, it was demonstrated that the application of Mega Cloth (subacromial bursa, concentrated bone marrow aspirate, and platelet-rich plasma) had a positive effect on cuff healing. 16 In contrast to this study, which did not have a comparison group, our study found that the clinical outcomes of the bursal augmentation and debridement group were better than those of the control group we designated as the debridement and acromioplasty group.

MRI evaluation provides information about the progression of tendon healing and retears. Sugaya et al 20 divided the postoperative cuff integrity into 5 subgroups in their study using oblique coronal, oblique sagittal, and transverse views of T2-weighted MRI scans. In a study comparing the outcomes between immediate surgical repair and delayed repair after a 6-month period of nonsurgical treatment, neither group showed evident retears based on MRI performed at 2 months postoperatively. At 12 months postoperatively, retears of Sugaya types 3 to 5 were detected in both groups, with no statistical difference between them. 10 In our study, 15 of 22 patients who underwent acromioplasty + augmentation (group B) had type 1 cuffs with normal appearance, while 7 of 18 patients who underwent acromioplasty + debridement (group A) had type 1 cuffs with normal appearance. Although there was no conversion to full-thickness tear in group B patients, the proportionally larger number of partial tears (5/18) in group A patients and the presence of full-thickness tears (3/18) in group A patients indicate the success of surgery performed with bursal augmentation. It is worth considering the potential influence of debridement in group A patients on the observed progression of tears within that group, while also noting that the absence of debridement in group B may have contributed to the lack of tear progression.

Limitations

The present study has some limitations, one of which is that it was a retrospective review of prospectively collected data. No statistical comparison was performed for the MRI results, and we had only 6 months’ worth of MRI scans. In addition, randomization was determined depending on the quality of the bursal tissues. The study sample was small, and there was no separate group included in the analysis consisting of patients who underwent acromioplasty without debridement. All surgical procedures were performed by a single surgeon, which may have introduced a potential bias in surgical technique and individual variations in patient outcomes. Also, it was challenging to blind the MRI readers to the cases, and this could potentially have influenced their interpretations and introduced bias into the assessment of tear progression.

Conclusion

Biological augmentation of the subacromial bursa in arthroscopic repair of bursal-sided PT-RCTs has emerged as a potential strategy to enhance tendon healing. Notably, patients who received this treatment modality demonstrated superior clinical outcomes, as evidenced by improved outcome scores, when compared with those who underwent acromioplasty and debridement alone.

Footnotes

Final revision submitted June 9, 2023; accepted June 19, 2023.

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this contribution. AOSSM checks author disclosures against the Open Payments Database (OPD). AOSSM has not conducted an independent investigation on the OPD and disclaims any liability or responsibility relating thereto.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Sağlık Bilimleri Üniversitesi (reference No. 10.10.2022-84-598).

References

- 1. Bhatia DN. Arthroscopic biological augmentation for massive rotator cuff tears: the biceps-cuff-bursa composite repair. Arthrosc Tech. 2021;10(10):e2279–e2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bhatia DN. Arthroscopic bursa-augmented rotator cuff repair: a vasculature-preserving technique for subacromial bursal harvest and tendon augmentation. Arthrosc Tech. 2021;10(5):e1203–e1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chung SW, Kim JY, Yoon JP, Lyu SH, Rhee SM, Oh SB. Arthroscopic repair of partial-thickness and small full-thickness rotator cuff tears: tendon quality as a prognostic factor for repair integrity. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(3):588–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crisan M, Yap S, Casteilla L, et al. A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(3):301–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dwyer T, Razmjou H, Henry P, Misra S, Maman E, Holtby R. Short-term outcomes of arthroscopic debridement and selected acromioplasty of bursal- vs articular-sided partial-thickness rotator cuff tears of less than 50. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(8):2325967118792001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dyrna F, Zakko P, Pauzenberger L, McCarthy MB, Mazzocca AD, Dyment NA. Human subacromial bursal cells display superior engraftment versus bone marrow stromal cells in murine tendon repair. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(14):3511–3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ellman H. Diagnosis and treatment of incomplete rotator cuff tears. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(254):64–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Freislederer F, Dittrich M, Scheibel M. Biological augmentation with subacromial bursa in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthrosc Tech. 2019;8(7):e741–e747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fukuda H. Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears: a modern view on Codman’s classic. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(2):163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim YS, Lee HJ, Kim JH, Noh DY. When should we repair partial-thickness rotator cuff tears? Outcome comparison between immediate surgical repair versus delayed repair after 6-month period of nonsurgical treatment. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(5):1091–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Klatte-Schulz F, Thiele K, Scheibel M, Duda GN, Wildemann B. Subacromial bursa: a neglected tissue is gaining more and more attention in clinical and experimental research. Cells. 2022;11(4):663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lanham NS, Swindell HW, Levine WN. The subacromial bursa: current concepts review. JBJS Rev. 2021;9(11). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lawson-Smith M, Al-Maiyah M, Goodchild L, Fourie JMB, Finn P, Rangan A. Do partial thickness, bursal side cuff tears affect outcome following arthroscopic subacromial decompression? A prospective comparative cohort study. Shoulder Elbow. 2015;7(1):24–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lhee SH, Jo YH, Kim BY, et al. Novel supplier of mesenchymal stem cell: subacromial bursa. Transplant Proc. 2013;45(8):3118–3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morikawa D, Johnson JD, Kia C, et al. Examining the potency of subacromial bursal cells as a potential augmentation for rotator cuff healing: an in vitro study. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(11):2978–2988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Muench LN, Kia C, Berthold DP, et al. Preliminary clinical outcomes following biologic augmentation of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using subacromial bursa, concentrated bone marrow aspirate, and platelet-rich plasma. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2020;2(6):e803–e813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pancholi N, Gregory JM. Biologic augmentation of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using minced autologous subacromial bursa. Arthrosc Tech. 2020;9(10):e1519–e1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Põldoja E, Rahu M, Kask K, Weyers I, Kolts I. Blood supply of the subacromial bursa and rotator cuff tendons on the bursal side. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(7):2041–2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Song N, Armstrong AD, Li F, Ouyang H, Niyibizi C. Multipotent mesenchymal stem cells from human subacromial bursa: potential for cell based tendon tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20(1-2):239–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sugaya H, Maeda K, Matsuki K, Moriishi J. Functional and structural outcome after arthroscopic full-thickness rotator cuff repair: single-row versus dual-row fixation. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(11):1307–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tsuchiya S, Davison EM, Rashid MS, et al. Determining the rate of full-thickness progression in partial-thickness rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30(2):449–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Utsunomiya H, Uchida S, Sekiya I, Sakai A, Moridera K, Nakamura T. Isolation and characterization of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from shoulder tissues involved in rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(3):657–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weber SC. Arthroscopic debridement and acromioplasty versus mini-open repair in the treatment of significant partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(2):126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wolff AB, Sethi P, Sutton KM, Covey AS, Magit DP, Medvecky M. Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(13):715–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xiao J, Cui G. Clinical and structural results of arthroscopic repair of bursal-side partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(2):e41–e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang Y, Zhai S, Qi C, et al. A comparative study of arthroscopic débridement versus repair for Ellman grade II bursal-side partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29(10):2072–2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]