Abstract

The respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) fusion (F) protein/polysorbate 80 (PS80) nanoparticle vaccine is the most clinically advanced vaccine for maternal immunization and protection of newborns against RSV infection. It is composed of a near-full-length RSV F glycoprotein, with an intact membrane domain, formulated into a stable nanoparticle with PS80 detergent. To understand the structural basis for the efficacy of the vaccine, a comprehensive study of its structure and hydrodynamic properties in solution was performed. Small-angle neutron scattering experiments indicate that the nanoparticle contains an average of 350 PS80 molecules, which form a cylindrical micellar core structure and five RSV F trimers that are arranged around the long axis of the PS80 core. All-atom models of full-length RSV F trimers were built from crystal structures of the soluble ectodomain and arranged around the long axis of the PS80 core, allowing for the generation of an ensemble of conformations that agree with small-angle neutron and X-ray scattering data as well as transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images. Furthermore, the hydrodynamic size of the RSV F nanoparticle was found to be modulated by the molar ratio of PS80 to protein, suggesting a mechanism for nanoparticle assembly involving addition of RSV F trimers to and growth along the long axis of the PS80 core. This study provides structural details of antigen presentation and conformation in the RSV F nanoparticle vaccine, helping to explain the induction of broad immunity and observed clinical efficacy. Small-angle scattering methods provide a general strategy to visualize surface glycoproteins from other pathogens and to structurally characterize nanoparticle vaccines.

Keywords: respiratory syncytial virus, nanoparticle vaccine, fusion glycoprotein, small-angle neutron scattering, polysorbate micelle

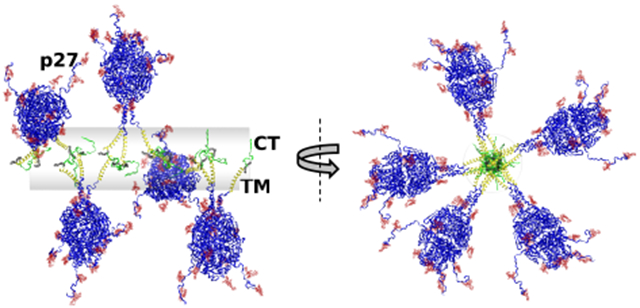

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Protein nanoparticles have long been recognized for their potential as powerful immunogens and candidates for vaccine development.1,2 Indeed, nanoparticle vaccines have become important weapons in the battle against infectious disease. Presentation of multiple copies of viral antigens, which are key targets for immunorecognition, on the surface of the nanoparticle mimics the surface of the pathogen and is thought to be one of the reasons for their ability to generate superior immune response.3,4 Structural characterization of vaccine nanoparticles to determine particle size, antigen density, and presentation can help to understand how these molecular features may enhance immunogenicity. However, protein nanoparticles consist of amphipathic glycoprotein antigens with transmembrane (TM) domains that must be stabilized by detergent, and this inherent complexity presents great challenges for high-resolution structural studies.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a nonsegmented, negative-strand, enveloped RNA virus in the Pneumoviridae family. It is a major cause of severe lower respiratory tract infection in newborns, young children, and the elderly. The global disease burden includes over 30 million infections, >3 million hospitalizations, and 48 000–75 000 deaths in young children.5 Children <5 years of age are the most susceptible and account for 45% of RSV-related fatalities with the vast majority (>90%) in developing countries.5 Disease burden in the elderly is also substantial with 1.5 million infections, >300 000 hospitalizations, and 14 000 in-hospital deaths.6 Although there is significant disease burden, there are no licensed RSV vaccines and palivizumab (Synagis) is the only U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved preventative treatment for high-risk newborns.7-9

The RSV fusion (F) glycoprotein is a major focus of vaccine development since it is >90% conserved between RSV subgroups,10 essential for virus/host membrane fusion and virus entry into the host cell,11 and a primary target of host immune defense with multiple key neutralizing epitopes.12-15 RSV F glycoprotein is a type 1 integral membrane protein that is produced as an inactive precursor (F0) of 574 amino acids that assemble as trimers. RSV F0 has two fUrin protease cleavage sites at positions R109 (site I) and R136 (site II) that are post-translationally processed to produce three fragments: the short N-terminal F2 subunit, a larger C-terminal F1 subunit with the fusion peptide (FP), and an intervening 27 amino acid peptide (p27) that is removed to expose the hydrophobic FP, a step necessary for infection. Fusion of RSV and host-cell membranes is driven by conformational changes involving 3-heptad repeats (3-HRA and 3-HRB) located at opposite ends of the RSV F F1 subunit. The prefusion conformation of RSV F is triggered to expose the N-terminus of the FP, which extends from the hydrophobic cavity in a hairpin F protein conformation to engage the host-cell membrane. To complete membrane fusion, the metastable RSV F hairpin intermediate refolds, joining 3-HRA and 3-HRB, to form an elongated 6-heptad bundle (6HB) in the postfusion RSV F conformation, effectively aligning and fusing the virus and host-cell membrane.

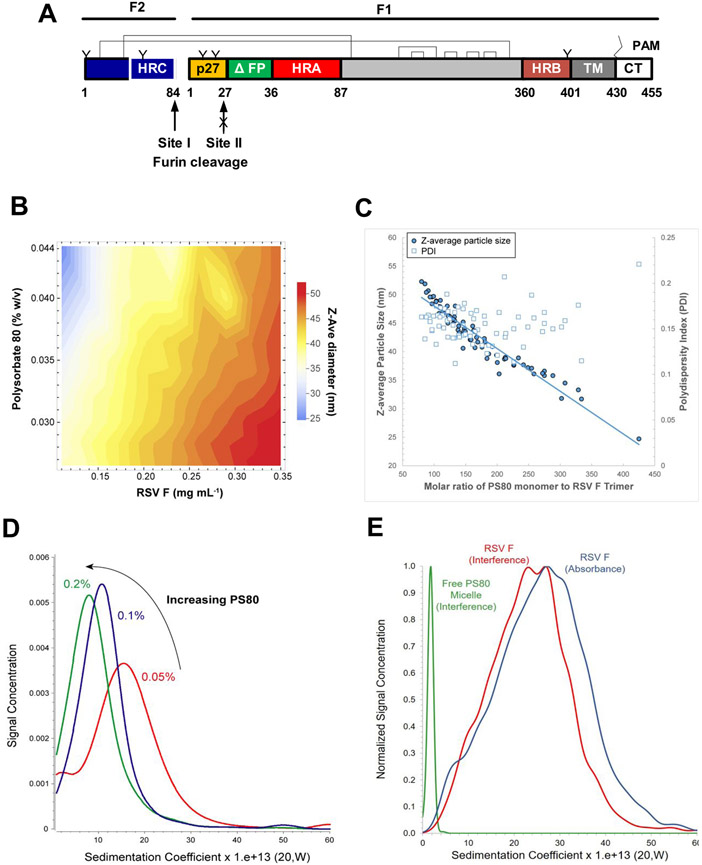

We have designed a stable RSV F construct in which the fusion peptide was truncated (ΔFP) and furin cleavage site II was mutated to be protease-resistant. Processing at site I generates the F2 subunit and the F1 subunit with the p27 fragment retained on the N-terminus and the native RSV TM and cytoplasmic tail (CT) retained on the C-terminus. Two disulfide bonds link the F2 and F1 subunits (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Linear diagram and hydrodynamic properties of RSV fusion glycoprotein. (A) Linear diagram of the primary structure of the RSV F sequence used to produce the synthetic gene. RSV F has two furin cleavage sites (arrow) that flank an intervening 27-residue peptide (p27, yellow). Site II was mutated (KKRKRR→KKQKQQ) to be resistant to proteolytic cleavage (arrow with “X”) with p27 retained on the N-terminus of the F1 subunit and the first 10 amino acids deleted from the adjacent fusion peptide (ΔFP, green). Two intermolecular disulfide bonds (C12–C320 and C44–C92) couple the F2 and F1 subunits. F1 disulfide bonds at positions C194–C224, C203–C214, C239–C249, C263–C274, and C297–C303 are indicated. The native transmembrane (TM, dark gray) domain and cytoplasmic tail (CT, white) were retained on the C-terminus of the F1 subunit. N-Linked glycosylation sites are indicated by “Y”; palmitoleic acid (PAM) is indicated by zig-zag line; and heptad repeats A, B, and C are indicated by HRA (red), HRB (brown), and HRC (blue), respectively. (B and C) Dynamic light scattering (DLS) particle size diameter (Z-ave, in nm) and polydispersity index (PDI) as a function of polysorbate 80 (PS80)-to-RSV F molar ratio. (D) Sedimentation coefficient distribution profiles of RSV F with 0.05–0.20% PS80. (E) Sedimentation coefficient distribution profiles of RSV F/PS80 at nominal concentrations, with data collected by 280 nm absorption (blue) and 655 nm Rayleigh interference (red). Data collected for formulation buffer only by Rayleigh interference (green). (D and E) The x-axis is labeled in Svedberg units (10−13 s).

Purified RSV F trimers formulated with polysorbate 80 (PS80) detergent form nanoparticles that, when visualized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), resemble rosette structures composed of different numbers of RSV F trimers.16 The RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle vaccine is immunogenic and produces protective immunity in cotton rats and maternal antibodies that protect neonatal baboons against pulmonary challenge with nonadapted human RSV. 17-19 In humans, the vaccine is immunogenic and safe in women of childbearing age20,21 and older adults22 and was recently evaluated as a maternal vaccine in a global phase 3 trial (NCT02624947).

The antigenic profile of the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle vaccine was examined using antigenic site-specific monoclonal antibodies to prefusion and postfusion F neutralizing epitopes.18 This study demonstrated that immunization with full-length RSV F trimer nanoparticles elicited neutralizing antibodies that target key conformation-dependent prefusion epitopes as well as conformation-independent epitopes common to prefusion and postfusion F conformers.18 The study further demonstrated that F-proteins expressed on the cell surface exhibit similar conformational flexibility and epitope profile. Flexibility of F-proteins as well as transient opening of F trimers may allow exposure of sequestered epitopes that are important for immunogenicity and protective immunity.23

Detailed structural studies are needed to understand the induction of broad immunity leading to the observed efficacy of the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle vaccine and to engineer more effective vaccines in general. Yet, structural studies of nanoparticle vaccines are not common. A challenge to determining the structure of membrane protein–detergent complexes is heterogeneity of the colloidal system in which the detergent mass may equal or exceed that of the protein.24 Atomistic structures of antigens have been mainly obtained by X-ray crystallography, which requires manipulation of the structure to stabilize it to obtain crystals. X-ray crystal structures are available for the ectodomain of the RSV F trimer in its prefusion12 and postfusion14 conformations. While they do not contain the TM or CT domains, they can serve as starting structures for all-atom structure modeling of full-length RSV F trimers.

Nanoparticle vaccines are often studied using negative stain TEM, as shown in recent studies of FDA-approved vaccines for influenza25 and human papillomavirus.26 Samples must be extensively manipulated for TEM studies, which may include dilution prior to staining, drying, and fixing on a grid, so the images obtained may not reflect the structure in solution. Thus, while TEM analysis of the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle has provided general morphology,16 solution structural details including shape and organization of RSV F trimers and PS80 in the nanoparticle could not be determined.

Small-angle neutron and X-ray scattering (SANS and SAXS) are powerful methods for determining the quaternary structure of large protein assemblies and complexes in solution.27 Due to the unique interaction of neutrons with hydrogen and deuterium isotopes, solution studies of complex molecular assemblies can be addressed using SANS in combination with contrast variation. Contrast between protein and detergent in the SANS measurement can be achieved by isotopic substitution of water with deuterium oxide (D2O) in the solvent. Under optimized solvent conditions, scattering from the RSV F protein and bound PS80 detergent was isolated and molecular components were characterized individually as they exist in the complex. This allowed not only for the calculation of stoichiometric ratios of the RSV F trimers and PS80 detergent in the nanoparticle vaccine but also for the determination of the spatial arrangement of the two components with respect to each other. This key information obtained from the SANS studies enabled all-atom modeling of an ensemble of conformations of full-length RSV F glycoprotein trimers in the nanoparticle for direct comparison to the small-angle scattering (SAS) data. The resultant structure models are consistent with TEM as well as hydrodynamic measurements by sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation (SV-AUC) and dynamic light scattering (DLS). This work represents the first solution study of full-length RSV F in a clinical stage RSV nanoparticle vaccine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RSV F Nanoparticle Vaccine.

RSV F/PS80 nanoparticles were constructed from the RSV A2 F gene sequence (GenBank Accession no. U63644) encoding the near-full-length fusion glycoprotein.28 The synthetic gene was codon-optimized (GenBank MN125707.1) for expression in Spondoptera frugiperda Sf9 (GeneArt, Regensburg, Germany). Furin cleavage site II was mutated (KKRKRR→KKQKqQ) to be protease-resistant and to retain the p27 fragment on the N-terminus of the F1 subunit. The adjacent FP was truncated by deletion of the first 10 amino acids (ΔFP), and the native TM and CT were retained on the C-terminus as previously described.16,29 The amino acid sequence of RSV F used for modeling can be found in Figure S1. RSV F trimers were extracted from detergent-lysed Sf9 cells grown in a 1000 L bioreactor and infected with the RSV recombinant baculovirus and purified by ion exchange, affinity chromatography, and cation exchange using a proprietary production similar to a previously reported process.30 The RSV F/PS80 nanoparticles were formulated in 22 mM (mmol L−1) sodium phosphate, pH 6.2, 150 mM sodium chloride, 1% (w/v) l-histidine, and a nominal concentration of 0.03% (w/v) PS80 (formulation buffer).

Aluminum Phosphate Adsorption of RSV F.

RSV F/PS80 sample was spiked with Adju-Phos (Brenntag Biosector) to a 3:1 alum:protein mass ratio and incubated at room temperature for 30 min with rotational mixing. The slurry was pelleted at 3000 rpm centrifugation for 10 min. To determine the PS80 detergent concentration, the resulting supernatant was recovered and treated with molar excess sodium hydroxide to de-esterify and quantitate oleic acid by RP-HPLC-UV (absorbance detection at a 195 nm wavelength) using a Waters C18 column (Milford, MA). For RSV F protein quantitation, the supernatant was analyzed by a separate RP-HPLC-UV method (absorbance detection at a 280 nm wavelength) using an Imtakt USA C18 column (Portland, OR). Both methods utilized Agilent HPLC systems (Santa Clara, CA). Duplicate Adju-Phos treatment and quantification were performed with the RSV F formulation buffer containing 0.04% PS80 as a control sample. Detergent and protein quantification were also performed on RSV F/PS80 samples and formulation buffer samples prior to Adju-Phos treatment to establish baseline recovery values. Results for these RP-HPLC assays are provided in Table S1.

Dynamic Light Scattering.

DLS was used to investigate the impact of PS80 concentration on the hydrodynamic size of the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle. RSV F/PS80 samples of varying RSV F concentrations (100–350 μg mL−1), each formulated with incremental amounts of PS80 detergent (0.25–0.44 mg mL−1), were loaded into 384-well Corning plates and equilibrated at 20 °C in a DynaPro PlateReader II DLS instrument (Wyatt Technology Corp., Santa Barbara, CA). Time-dependent intensity fluctuations of scattered laser light (819 nm, detection at 150°) were collected to produce autocorrelation functions, from which mean hydrodynamic diameters (Z-ave) and PDIs were determined by the method of Cumulants using the DYNAMICS instrument software.

Analytical Ultracentrifugation.

SV-AUC was performed using a ProteomeLab XL-I ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Indianapolis, IN). Samples were loaded into two-channel 12 mm Epon AUC cell assemblies, which were placed into an An-60 Ti rotor and equilibrated at 20 °C. In one experiment, SV-AUC was used to monitor changes in the sedimentation coefficient distribution profile of RSV F samples prepared in formulation buffer containing different concentrations of PS80. RSV F F/PS80 samples were formulated with 0.05, 0.10, and 0.20% PS80, which is in excess of the PS80 critical micellar concentration (CMC = 0.002% w/v).31 Sedimentation data were acquired using a rotor speed of 22 000 rpm and collected as radial intensity at 280 nm. The estimated partial specific volume applied for analysis of the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle sedimentation was 0.72 cm3 g−1.

SV-AUC coupled with Rayleigh interference detection was used to evaluate the presence of free PS80 micelles in the RSV F/PS80 vaccine formulation. Samples were formulated with 0.45 mg mL−1 RSV F and 0.032% PS80. Data were collected with UV detection at a 280 nm wavelength and a Rayleigh interference at a 655 nm wavelength. Centrifugation was performed at rotor speeds of 25 000 rpm (for RSV F/PS80 samples) and 50 000 rpm (for formulation buffer samples containing PS80 only), during which sedimentation data were collected as radial absorbance at a 280 nm wavelength and Rayleigh interference at a 655 nm wavelength. Reference channels were filled with matching formulation buffer. Different partial specific volumes were applied for analysis of RSV F/PS80 (0.81 cm3 g−1; see the Determination of Partial Specific Volume of RSV F/PS80 Nanoparticle by SV-AUC section) and formulation buffer with PS80 (0.90 cm3 g−1) samples, including in the calculations of molecular weight values reported in this study. Data were analyzed by parallel computation in UltraScan (AUC Solutions, LLC, Houston, TX) using two-dimensional spectrum analysis (2DSA)32,33 to remove time-invariant and radially-invariant noise and to fit the meniscus position as described.34 Sedimentation coefficient distributions were prepared from a 2DSA-Monte Carlo analysis of the data.35

Determination of Partial Specific Volume of RSV F/PS80 Nanoparticle by SV-AUC.

Stock samples of concentrated RSV F protein (2.2–2.4 mg mL−1) and PS80 (0.1% w/v) were diluted 10-fold into various ratios of formulation buffer, composed of either H2O or D2O solvent, to reach final D2O concentrations of 0, 15, 30, 50, 75, and 90% (v/v). The resulting RSV F samples were analyzed by SV-AUC at 25 000 rpm and 20 °C, with data collected as radial intensity at 280 nm wavelength. The apparent weight-average s20,w values derived from 2DSA fits were plotted as a function of the actual density of the formulation buffer. The inverse of the x-intercept of a linear regression model (when s20,w approaches zero) represents the partial specific volume for the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle. The partial specific volume value of 0.81 cm3 g−1 was calculated as an average of five replicate measurements (with a corresponding relative standard deviation of 1.9%; see Table S2 for all results) and is the value applied for the SV-AUC calculations involving the dual detection data, including the Mw determination.

Transmission Electron Microscopy and 2D Class Averaging.

TEM images of the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle were obtained by negative staining. The RSV F/PS80 sample was diluted to 6.13 μg mL−1 in formulation buffer without PS80. The RSV F/PS80 sample (3 μL) was applied to a nitrocellulose-supported 400-mesh copper grid and stained with uranyl formate. Electron microscopy was performed with an FEI Tecnai T12 electron microscope, operating at 120 keV equipped with an FEI Eagle 4 k × 4 k CCD camera. Images of each grid were acquired at multiple scales to assess the overall distribution of the specimen. High-magnification images were acquired at nominal magnifications of 110 000 × (0.10 nm/pixel), 52 000 × (0.21 nm/pixel), and 21 000 × (0.50 nm/pixel). The images were acquired at a nominal under focus of −2 to −1 μm (110 000×), −3 to −2 μm (52 000×), and −5 to −4 μm (21 000×) and electron doses of ~7–40 e/Å2.

For class averaging, particles were identified in high-magnification images prior to alignment and classification. The individual particles were selected and boxed out, and individual subimages were combined into a stack to be processed using reference-free classification. Individual particles in the 67 000× high-magnification images were selected using automated picking protocols.36 An initial round of alignments was performed on each sample, and from that, alignment class averages that appeared to contain recognizable particles were selected for additional rounds of alignment. These averages were then used to estimate the percentage of particles that resembled monomer and complexes. A reference-free alignment strategy based on the XMIPP processing package37 was used for particle alignment and classification. Algorithms in this package align the selected particles and sort them into self-similar groups of classes (NanoImaging Services, Inc., San Diego, CA).

SANS and SAXS Data Collection and Reduction.

Samples of RSV F/PS80 in formulation buffer containing 0% and 99% (v/v) D2O were prepared by buffer exchange using 10 000 MWCO centrifugal spin filter units (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA). The final RSV F protein concentrations of the 0% (v/v) or ~99% (v/v) D2O samples were determined by UV absorbance measurement at 280 nm as 1.7–2.1 mg mL−1. Based on data from RP-HPLC and Adju-Phos pull-down experiments, PS80 concentrations in the various samples were estimated to be 1.4–1.6 mg mL−1. The 0 and 99% D2O RSV F/PS80 samples were mixed volumetrically to obtain 12% (v/v) and 41% (v/v) D2O samples for SANS and SAXS experiments as described below. The amount of D2O in the buffers was subsequently confirmed by their neutron beam transmission factors.

The SANS measurements were performed on the Center for High Resolution Scattering (CHRNS) NGB 30 m SANS instrument at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Center for Neutron Research (NCNR, Gaithersburg, MD). A neutron wavelength, λ = 6 Å, with a wavelength spread of Δλ/λ = 0.15 was used. Scattered neutrons were detected with a 64 cm × 64 cm 2D position-sensitive detector with 128 × 128 pixels at a resolution of 0.5 cm/pixel. The data were reduced using the IGOR program with SANS macro-routines developed at the NCNR.38 The raw counts were normalized to a common neutron monitor count and corrected for the empty cell counts, background radiation, and nonuniform detector response. The data obtained from the samples were placed on an absolute scale by normalizing the scattered intensity to the incident beam flux. Finally, the data were radially averaged to produce the scattered intensity, I(q), versus q curves, where q = 4π sin(θ)/λ and 2θ corresponds to the scattering angle. Sample-to-detector distances of 13 m, 4 m, and 1.3 m were used for the measurements to cover the q-range between 0.004 and 0.5 Å−1. Due to the presence of higher incoherent neutron scattering background at higher H2O concentrations in the buffer, the maximum usable q value corresponding to interpretable scattering data after buffer subtraction decreases from ~0.3 to ~0.1 A−1 for the decreasing amounts of D2O in the buffer. PS80 scattering data were collected in 99% (v/v) D2O buffer as a control and RSV F/PS80 scattering data were collected in 12, 41, and 99% (v/v) D2O buffers.

Solution X-ray scattering data for RSV F/PS80 vaccine were acquired using the MOLMEX Ganesha instrument at the Institute for Bioscience and Biotechnology Research (IBBR, Rockville, MD). Copper Kα incident radiation with a wavelength of 1.542 Å produced by a Rigaku MicroMax 007HF rotating anode generator was monochromated and collimated using two sets of scatter-less slits. A Dectris Pilatus 300K detector was used to register the scattered radiation with the transmitted intensity monitored via the pin diode. Samples were kept at 5 °C (RSV F/PS80) or 25 °C (PS80 in formulation buffer) and exposed to the incident X-ray radiation for the duration of 16 sequential 900 s frames. Pixel intensity outliers due to the background radiation were removed, and the 2D data were corrected for the detector sensitivity profile and the solid angle projection for each pixel. The data were converted to one-dimensional scattering intensity curves, frame-averaged, and buffer-subtracted. Data sets acquired at sample–detector geometries of 1755 mm and 705 mm and slit openings of 0.2 mm and 0.8 mm, respectively, were merged to extend the accessible q-range from 0.006 to 0.4 Å−1.

PS80 scattering data were collected in 0% (v/v) D2O buffer as a control, and RSV F/PS80 scattering data were collected in 0 and 99% (v/v) D2O buffers. In addition to the stock concentrations, scattering data were acquired for 2-fold diluted samples to investigate concentration dependence that could arise from interparticle repulsion or shifts in the oligomerization equilibrium. Seeing no change with concentration, scattering curves at the highest sample concentrations were used for further analysis.

SANS and SAXS Data Analysis.

Guinier analysis was performed using PRIMUS39 for the SAXS data and the IGOR SANS macros38 for the SANS data. The GNOM program,40 which makes use of all of the data, rather than a limited data set at small q values, was used on the SAXS and SANS data to determine the distance distribution function, P(r), the radius of gyration, Rg, and the forward scattering intensity, . GNOM uses a regularized indirect Fourier transform (IFT) method that requires the stipulation of a maximum dimension, Dmax, beyond which P(r) = 0. Several values of Dmax were explored to find the range over which the P(r) function is stable. Dmax was chosen to be the lowest value that agreed with the Guinier Rg and fit the experimental data, by examination of residuals. Dmax values were explored manually rather than relying on an automated choice. Values at least ±10–20 Å were explored around the chosen values to ensure that they resulted in differences only in the tail region of P(r) and not in the peaks representing the most probable distances. Rg, , Dmax, and P(r) were also calculated using the SasView program (www.sasview.org/) for comparison.

SANS data for the PS80 component in the RSV F/PS80 complex, obtained in 41% D2O buffer, were fit to a solid cylinder model using SasView to constrain the all-atom models of the RSV F portion of the complex.

The stoichiometry of the RSV F/PS80 complex was calculated using the values obtained from all of the SAXS and SANS data to solve for the molecular weights of the RSV F and PS80 components. for a two-component complex can be written as

| (1) |

where and are the scattering contrasts for each component, and are the volumes of each component, and

| (2) |

are the mass fractions of each component. Here, , , and , are the scattering length densities of the components and the solvent, and the number density of scatterers, , was written as

| (3) |

where is the total concentration of the complex, is the total molecular weight of the complex, and is Avogadro’s number. Furthermore, the volumes were written as

| (4) |

where and are the partial specific volumes of each component. Thus, can be written in terms of the individual molecular weights, contrasts, and partial specific volumes of each component. and can then be obtained by solving a joint set of equations. At least two equations, meaning values from two data sets at two different contrasts, must be used to solve for the molecular weights of the RSV F and PS80 components. This analysis assumes that the values are on an absolute scale in cm−1 and that all of the RSV F and PS80 are bound in the complex with no free RSV F or PS80 in the solution. The latter assumption is supported by data from SV-AUC and RSV F-Adju-Phos pull-down experiments, neither of which detected the presence of free PS80 in solution. Polydispersity was not taken into account.

The scattering contrasts for the RSV F and PS80 components were calculated using the Contrast Calculator41 in SASSIE-web.42,43 For RSV F, the amino acid sequence of one monomer was used, whereas for PS80, the chemical formula for one monomer was used assuming a mass density of 1.0 g cm−3 and no exchangeable H atoms. Partial specific volumes of 0.74 and 0.903 cm3 g−1 were used for the RSV F and PS80 components, respectively. The concentration and contrast values that were used are listed in Table S3.

RSV F/PS80 Nanoparticle Model Structures.

Two types of atomistic RSV F trimer models were created using available coordinates from X-ray structures for the RSV F prefusion (Protein Data Bank identifier, PDB ID) 4JHW12 and the RSV F postfusion PDB ID 3RKI14 trimers. These coordinates were used as frameworks to build two qualitatively structurally distinct five-trimer nanoparticle models to analyze the experimental scattering data. Missing and disordered atoms absent in the starting framework coordinates were added using PSFGEN44 to create starting trimer models using the CHARMM force field45 that were energy-minimized using NAMD.44 DISU patches were used to identify disulfide bonds between residues C12 (F2)–C320 (F1) and C44 (F2)–C92 (F1) and F1 residues C194–C224, C203–C214, C239–C249, C263–C274, and C297–C303.

The missing transmembrane (TM) helical region for each monomer was modeled using Phyre246 to identify and align homologous structures to the TM portion of F1, i.e., residues 406–430. In all cases, the homologous structures were identified as transmembrane helices. The structure with the best sequence alignment was chosen (PDB ID 5XSY),47 and the nonmatching residues were replaced with the correct residues in the RSV F sequence using PSFGEN.

Starting coordinates for palmitoleic acid (PAM) were from PDB ID 3ZUI.48 Force field parameters for PAM were generated using the CHARMM 36 force field49 by adapting analogous parameters from 3-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-d-glycero-1-phosphatidylcholine (POPC). The resulting all-atom model of PAM was energy-minimized using NAMD. A patch to create a thioester linkage between PAM and cysteine 431 from F1 of the framework monomers was used to add a single PAM to each monomer of the trimer framework models.

The composition of glycan was chosen to be M3F,50 and force field parameters and starting coordinates were generated using CHARMM 3651 using the appropriate 1–6, 1–3, and 1–4 linkages of the monosaccharide components and β–β patches to create bonds between monosaccharide units. The starting glycan model was then energy-minimized using NAMD. Linkages of the model M3F coordinates of each of the five glycans per monomer utilized the NGLB patch to glutamine residues 2 from F2 and 7, 17, 45, and 381 from F1. Following the addition of PAM and glycan coordinates to the model protein trimer, the entire system was energy-minimized using NAMD followed by 10 ns molecular dynamics run in the NVT ensemble using the TIP3P water model.52 Nonwater coordinates of each complete trimer framework model were extracted and used in subsequent modeling efforts.

To build starting models composed of five RSV F trimer units, each trimer was aligned along its long axis with the center of mass of residues 425–455 of F1 placed in the cylindrical region that best-fits the SANS data in 41% D2O, where only the scattering from the PS80 is being measured. The long axis of the trimer was defined as the z-axis. The short dimension of the PS80 best-fit cylinder (radius = 40 Å) also lies along this axis. The coordinates of each RSV F trimer unit were replicated four times with each initially displaced by 62 Å along the x-axis (the long dimension of the cylinder) so that the RSV F five-trimer models spanned approximately 280 Å corresponding to the long dimension of the best-fit PS80 cylinder. The value of the displacement was varied between 50 and 70 Å in subsequent simulations to obtain starting structures with different distances between the RSV F trimers. Configurations were then sampled by choosing a random RSV F trimer unit (2 through 5) and rotating an individual trimer about the x-axis by a random angle. Structures with atomic overlap between any two trimer units were discarded.

Conformational space coverage was quantified for the ensembles of five RSV F trimer nanoparticles by enumerating the number of occupied volume pixels (voxels) in 3D space as described by Zhang et al.53 using cubic voxels of length 5 Å in x, y, and z. Convergence was found within ~1000 accepted structures. Typical ensembles contained between 17 000 and 18 000 accepted structures. Thus, convergence in conformation space was assured. The structures in the ensemble were clustered as described53 using a 40 Å voxel size in x, y, and z to identify between 700 and 900 representative structures per ensemble.

For each representative structure, the SAXS profile was calculated using the SasCalc module54 implemented in SASSIE-web for comparison to the data using the reduced

| (5) |

where equals the number of data points, and are the experimental and calculated intensity values, respectively, at each point , and is the error on the experimental measurement at each point. To explore the effect of the flexible regions on the calculated scattering curves, Monte Carlo simulations were performed on residues 78–84 for F2 and residues 1–27 and 436–455 for F1 for a representative RSV F trimer structure using the torsion angle Monte Carlo (TAMC) module53 in SASSIE-web. SAXS profiles were calculated for each structure in the resultant ensemble to show that the flexible regions do not change the basic shape of the RSV F trimer scattering curves. Similar Monte Carlo simulations were performed on residues 1–27 of each trimer in the RSV F five-trimer complex. Calculated SAXS curves showed that the flexible regions do not change the basic shape of the RSV F five-trimer scattering curves.

RESULTS

Dynamic Light Scattering and Sedimentation Velocity Analytical Ultracentrifugation.

A contour plot of the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle size (Z-average) as a function of PS80 and RSV F protein concentrations is shown in Figure 1B. Nanoparticle samples in which PS80 and RSV F concentrations were at opposite extremes (i.e., highest and lowest PS80-to-RSV F ratios) had variable hydrodynamic diameters with a range of about 25–52 nm. At a fixed concentration of PS80, increasing RSV F concentration correlated with an increase in particle size, while increasing PS80 concentration at a fixed RSV F concentration caused a decrease in particle size.

These results indicate that the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle size is inversely proportional to the PS80-to-RSV F ratio and does not change when this ratio is held constant. The DLS results were further analyzed to calculate the PS80-to-RSV F molar ratio and determine the dependence of hydrodynamic size and polydispersity index (PDI) on this ratio. PDI is a dimensionless measure of the broadness of the size distribution, and values greater than 0.5 can indicate significant heterogeneity. From high to low molar ratios of PS80 to RSV F, hydrodynamic diameter increased linearly (Figure 1C, blue circles) and the PDI was relatively constant in the range of 0.1–0.2 (Figure 1C, open boxes).

Figure 1D shows that the sedimentation coefficient (s20,W) decreased with increasing PS80 concentration with a noticeable decrease in the width of the sedimentation coefficient distribution between 0.05 and 0.10%. These results indicate that the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle size is related to the PS80-to-protein molar ratio and are consistent with DLS results and provide evidence that the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle formation is not driven by nonspecific or uncontrolled protein aggregation, but rather is the product of well-defined interactions between RSV F trimers and PS80 molecules. As PS80 concentration was increased, the width of the sedimentation coefficient distribution decreased, which reflects a decrease in population heterogeneity. This change in the sedimentation distribution is potentially due to the molecular mass and shape of the nanoparticle becoming more uniform as the molar ratio of PS80 to RSV F is increased.

Figure 1E illustrates that the weight-average s20,W value of free PS80 micelles, measured for a control sample of formulation buffer by Rayleigh interference, was determined as approximately 2 Svedbergs (S, 10−13 s), while the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle sample had no interference signal near 2 S, indicating that all PS80 was associated with the RSV F protein.

A protein-specific adsorption assay also confirmed that the PS80 detergent is tightly bound to the RSV F protein (Aluminum Phosphate Adsorption of RSV F section and Table S1). In addition, the absorbance and interference profiles largely overlapped, which was also consistent with co-sedimentation of the PS80 with RSV F (Figure 1E). Therefore, most if not all of the PS80 molecules in solution are engaged in interactions with the hydrophobic TM regions of the RSV F trimers.

The offset of the interference and absorbance data indicates that the smaller species have a higher PS80-to-RSV F ratio, while the larger species have a lower PS80-to-RSV F ratio, which is consistent with the DLS results (Figure 1B,C). Based on the weight-average sedimentation coefficient, and the experimentally determined partial specific volume of 0.81 cm3 g−1 for the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle (Determination of Partial Specific Volume of RSV F/PS80 Nanoparticle by SV-AUC section and Table S2), the molecular weight (Mw) was estimated as 1000–1200 kDa (from the D50 values for the absorbance and interference distribution data). Based on D10 and D90 values of 500 and 2400 kDa, respectively, nanoparticles may contain between two and nine RSV F trimers, with an average of approximately five trimers per nanoparticle.

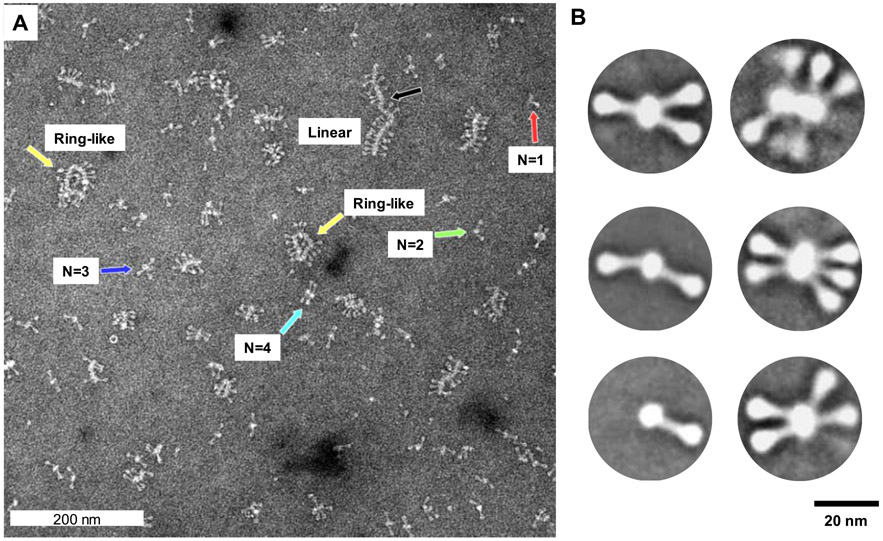

Transmission Electron Microscopy and 2D Class Average Images.

High-magnification (52 000×) TEM images show RSV F/PS80 nanoparticles of varying oligomeric states, with RSV F trimers protruding from a central core (Figure 2A). Single RSV F trimers were rarely observed. Larger oligomers of up to 14 trimers were organized end-to-end to form ring-like and elongated linear structures. The reason for the formation of ring structures in TEM may be due to the ends of the linear chains, which are not capped and are thus expected to be surface-active. Closure into a ring may help to form a cap and stabilize the structure. Given that the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle is a soft material, such structures are likely artifacts of the negative staining sample preparation for TEM.55 Since the TEM sample is deposited on a hydrophobic grid, mixed with exogenous metal salt fixative, and dried, there is a gradual increase in the concentration of the fixative and soluble-dispersed sample. These changes may lead to a transition in the solution and produce structures that are not fully representative of the structures present in solution.

Figure 2.

Transmission electron microscopy and 2D imaging of RSV F/PS80 nanoparticles. (A) Representative electron microscopy images of negatively stained RSV F/PS80 nanoparticles at a magnification of 52 000 × (0.21 nm/pixel). Discrete nanoparticles of a single RSV F trimer (red arrow), two RSV F trimers (green arrow), three RSV F trimers (blue arrow), four RSV F trimers (teal), large ring-like oligomers of 10–12 RSV F trimers (yellow arrows), and large oligomers of 14 or more RSV F trimers organized end-to-end (black arrow). (B) 2D class average images of nanoparticles with one to six RSV F trimers. The RSV F trimers have a 16–22 nm length with a head of approximately 5–6 nm that tapers to a 2–3 nm wide stalk associated with a central core of width approximately 8–10 nm and variable length depending on the number of RSV F trimers.

The two-dimensional (2D) class average images are the average structures obtained from a large number of micrographs containing thousands of particles.56 Thus, the resultant images are more statistically robust compared to those obtained in the earlier TEM studies.16 The 2D class average images in Figure 2B show a distribution of particles with one to six RSV F trimers joined tail-to-tail radiating from a central core.

The RSV F trimers have a length of 16–22 nm with a 5–6 nm head width that tapers into a thinner 2–3 nm stem. The RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle has a central core of width approximately 8–10 nm and variable length depending on the number of RSV F trimers. Although larger species were observed, their low abundance and heterogeneous morphology did not impact the class averaging.

Small-Angle X-ray and Neutron Scattering (SAXS and SANS).

The SAXS data and the SANS data that were collected for RSV F/PS80 samples prepared in 0, 99, or 12% D2O, where the RSV F component of the nanoparticle is expected to dominate scattering, are shown in Figure 3A. The SANS data58 in Figure 3B were collected for RSV F/PS80 samples prepared in 41% D2O where the PS80 component dominates scattering. The corresponding Guinier plots are shown in Figure 4. The resultant parameters from both the Guinier and P(r) analyses are shown in Table 1, and a complete tabulation of essential SAS data acquisition, analysis, and fitting information is given in Table S5, as recommended in Trewhella et al.58 Small differences between the values of the fitted Dmax parameters for the P(r) fits of the various SAXS and SANS data (Figure 3 and Table 1) reflect both varying experimental data uncertainties and varying relative contributions to the signal of the micellar and protein components.

Figure 3.

SANS and SAXS data from RSV F/PS80 nanoparticles (A and B) and PS80 (C). The left panels show the I(q) vs q scattering intensities of the SANS and SAXS data. The right panels show the distance distribution functions, P(r) vs r, which were obtained via regularized indirect Fourier transform (IFT) analysis.40,57 P(r)max = 1.0 for ease in comparing the shapes of the curves. Error bars on the data represent standard errors of the mean with respect to the number of pixels used in the data averaging. Error bars on the distance distribution functions are standard deviations based on multiple fits to the data using a series of Monte Carlo simulations.57 The solid lines are the fits to I(q) that were made during the IFT analysis. The corresponding residuals are shown in Figure S2.

Figure 4.

Guinier plots of SANS and SAXS data. (A) RSV F/PS80 nanoparticles and (B) PS80. The solid lines are the Guinier fits to the data that produced the Rg and values stated in the text and in Table 1. Error values are propagated from the standard error of the mean uncertainties in the SAXS and SANS data (errors on the Guinier fits are higher for the SAXS data due to the limited number of points in the Guinier region).

Table 1.

Radius of Gyration and Forward Scattering

| sample | concentrationa (mg mL−1) | Guinier | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rg (Å) | (cm−1) |

qR

g

|

q-fit range (Å−1) |

b | ||||

| low | high | low | high | |||||

| RSV F/PS80 | ||||||||

| 0% D2O (SAXS) | 3.1 | 164 ± 62 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 0.98 | 1.25 | 0.0060 | 0.0076 | 0.72 |

| 99% D2O (SAXS) | 3.1 | 145 ± 22 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 0.87 | 1.21 | 0.0060 | 0.0084 | 0.16 |

| 99% D2O (SANS) | 3.1 | 145.4 ± 1.6 | 8.2 ± 0.1 | 0.56 | 1.20 | 0.0038 | 0.0083 | 0.99 |

| 12% D2O (SANS) | 3.6 | 145 ± 9 | 0.60 ± 0.03 | 0.56 | 1.20 | 0.0038 | 0.0083 | 0.94 |

| 41% D2O (SANS) | 3.1 | 84 ± 7 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.46 | 1.20 | 0.0055 | 0.0143 | 0.22 |

| PS80 | ||||||||

| 0% D2O (SAXS) | 1.0 | 47 ± 3 | 0.010 ± 0.001 | 0.71 | 1.22 | 0.0149 | 0.0259 | 0.22 |

| 99% D2O (SANS) | 1.6 | 32.2 ± 0.1 | 0.745 ± 0.002 | 0.38 | 1.22 | 0.0119 | 0.0379 | 0.73 |

| sample | concentrationa (mg mL−1) | P(r) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rg (Å) | (cm−1) | Dmax (Å) | qmax (Å−1) | total est.c | ||

| RSV F/PS80 | ||||||

| 0% D2O (SAXS) | 3.1 | 168.5 ± 0.6 | 2.01 ± 0.01 | 550 | 0.3 | 0.70 |

| 99% D2O (SAXS) | 3.1 | 149.1 ± 0.4 | 2.28 ± 0.01 | 550 | 0.3 | 0.62 |

| 99% D2O (SANS) | 3.1 | 146 ± 1 | 8.08 ± 0.03 | 500 | 0.3 | 0.72 |

| 12% D2O (SANS) | 3.6 | 151 ± 4 | 0.60 ± 0.01 | 500 | 0.08 | 0.87 |

| 41% D2O (SANS) | 3.1 | 86 ± 3 | 0.167 ± 0.005 | 300 | 0.1 | 0.66 |

| PS80 | ||||||

| 0% D2O (SAXS) | 1.0 | 44.8 ± 0.4 | 0.099 ± 0.001 | 110 | 0.2 | 0.54 |

| 99% D2O (SANS) | 1.6 | 32.5 ± 0.1 | 0.750 ± 0.002 | 100 | 0.3 | 0.93 |

For RSV F/PS80, the concentration is the total concentration of RSV F and PS80.

Reduced (eq 5).

PS80 control.

Guinier plots of the SAXS and SANS data for the PS80 control sample show a linear Guinier range (Figure 4B). SAXS data for the PS80 sample in 0% D2O buffer resulted in a radius of gyration (Rg) value of 44.8 Å, using a Dmax value of 110 Å. From the SANS data for the PS80 sample in 99% D2O buffer, a smaller Rg of 32.5 Å was determined for approximately the same Dmax value (Table 1).

Analysis of the SAXS data for the PS80 micellar structure by the distance distribution function, P(r), reveals features such as a negatively valued minimum at r = 35 Å (Figure 3C, right panel). This observed shape is consistent with a model exhibiting lower electron density in the interior (containing hydrocarbon-rich fatty acid chains) and higher electron density in the exterior of the particle (containing oxygen-rich hydrophilic head groups).59 On the other hand, the P(r) function from the SANS data in 99% D2O buffer shows only one peak with a maximum at r = 35 Å, suggesting that the PS80 particle can be modeled as a single-phase object at these buffer conditions. The smaller Rg value obtained from SANS (≈32 Å) as compared with that from SAXS (≈45 Å) is consistent with SAXS being more sensitive to the head groups than SANS under these particular buffer conditions.

RSV F/PS80.

Guinier plots for the RSV F/PS80 SAXS and SANS data are linear (Figure 4A). SAXS and SANS data for RSV F/PS80 in 0 and 99% D2O (buffer conditions that are expected to be sensitive to both the RSV F protein and PS80 components) resulted in Rg values between 146 and 168.5 Å, using Dmax values of 500–550 Å. For the SANS sample in 12% D2O buffer (where RSV F protein is the dominant scattering component), Rg = 151 Å, using a Dmax value of 500 Å. The SANS sample in 41% D2O buffer (where PS80 is the dominant scattering component) resulted in Rg = 86 Å, using a Dmax value of 300 Å (Table 1). The 41% D2O data were also fit to a solid cylinder model to yield a radius of 40 ± 5 Å and a length of 280 ± 20 Å, with neutron scattering length densities of 5.7 (10−7 Å−2) for the PS80 component and 1.5 (10−6 Å−2) for the solvent. These dimensions are consistent with Rg = 86 ± 3 Å obtained from the P(r) analysis. The 41% D2O data along with the fitted SANS intensity curve are shown in Figure S3.

The values in Table 1, obtained from five data sets for RSV F/PS80 samples spanning all D2O concentrations and measured by both SANS and SAXS, were used for the stoichiometry analysis. Equations 1-4 (see the SANS and SAXS Data Analysis section) were used to solve for the Mw of the RSV F and PS80 components using seven different combinations of the five data sets (Table S4). The concentration and contrast values that were used are listed in Table S3. The Mw of the RSV F component was between 909 and 1073 kDa and that of the PS80 component was between 433 and 469 kDa, with the total Mw of the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle between 1345 and 1506 kDa. Taking the average of the results from the seven calculations, Mw (RSV F) = 965 ± 23 kDa, Mw (PS80) = 454 ± 6 kDa, and Mw (rSV F/PS80) = 1419 ± 20 kDa (Table S4), where the uncertainties are the standard errors of the mean. The results suggest that, on average, the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle consists of five RSV F trimers (180 kDa each) and 350 PS80 molecules (1310 Da each).

It is apparent from Table S3 that the contrast match point for RSV F is near 41% D2O, where the contrast for RSV F is only 0.033 (10−6 Å−2) and that of PS80 is near 12% D2O, where the contrast for PS80 is only 0.2 (10−6 Å−2). Thus, the PS80 component dominates the scattering in 41% D2O and the RSV F component dominates in 12% D2O. P(r) plots in Figure 3 combined with the calculated Rg values show that the PS80 component (Figure 3A) is significantly smaller than the RSV F component (Figure 3B, 12% D2O and SAXS). While the Rg and Dmax values are similar for the SANS data in 12 and 99% D2O buffers as well as for the SAXS data, the P(r) plots in Figure 3A show a clear difference, i.e., there is a higher probability of distances between r = 200 and 300 Å for the SANS data in 12% D2O buffer and the SAXS data (blue, black, and red curves) than for the SANS data in 99% D2O buffer. The 99% D2O buffer SANS data contain contributions from both RSV F and PS80 components, whereas the 12% D2O buffer data is mainly from the RSV F component.

The combined results from the Guinier, P(r), and stoichiometry analyses show that the RSV F component in the complex has Rg ≈ 150 Å, Dmax ≈ 500 Å, and Mw ≈ 950 kDa, whereas the PS80 component in the complex has Rg ≈ 90 Å, Dmax ≈ 300 Å, and Mw ≈ 450 kDa. The RSV F/PS80 complex has Rg ≈ 150 Å, Dmax ≈ 500 Å, and Mw ≈ 1400 kDa. The results are consistent with DLS and SV-AUC analysis, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Size and Mass Analysis of the RSV F/PS80 Nanoparticle

| DLS |

SV-AUCa |

SANSb/SAXS |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-ave (nm) | PDI | s20,Wc (Svedbergs) | Mwd (kDa) | Dmax (Å) | Rg (Å) | Mw (kDa) | |

| RSV F/PS80 | 25–52 | 0.1–0.2 | 27.04 | 1200 | 500–550 | 145–170 | 1419 ± 20 |

| RSV F component | 500 | 145–153 | 965 ± 23 | ||||

| PS80 component | 300 | 84–90 | 454 ± 6 | ||||

| Free PS80 control | 2.0 | 100 | 32–47 | ||||

SV-AUC results calculated from absorbance detection at 280 nm.

SANS values reported for samples in 99% D2O buffer, thus accounting for both RSV F protein and PS80 detergent scattering contributions. RSV F and PS80 component contributions are from SANS data at the respective D2O match point.

s20,W values are reported as weighted average sedimentation coefficient.

Mw value is calculated using a partial specific volume of 0.81 cm3 g−1 and reported using D50 statistics.

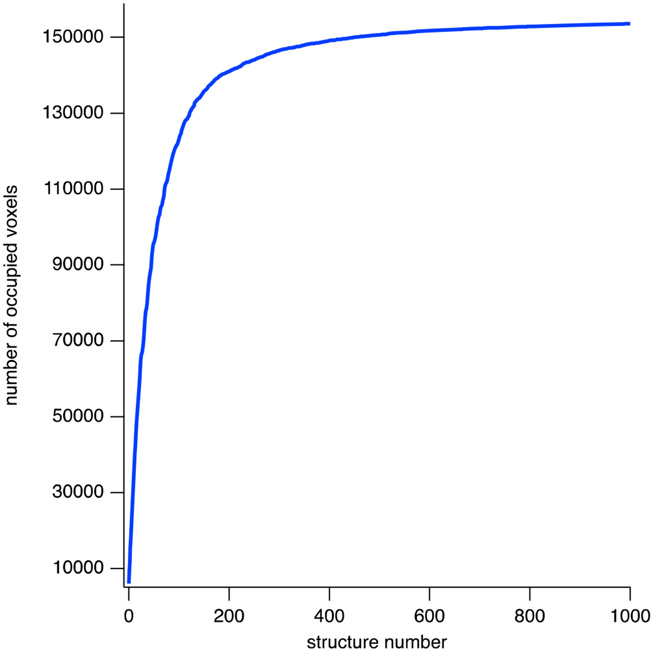

RSV F/PS80 Modeling for SAXS Calculations and 2D Projections.

X-ray crystal structures of the prefusion and postfusion RSV F trimer ectodomains facilitated the building of all-atom structures of the exact stable RSV F construct that is present in the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle vaccine, including the TM and CT regions and the carbohydrate and fatty acid moieties. The left panels in Figure 5B,C show the individual RSV F trimer structures, and their arrangement in an antiparallel, offset configuration of a five-trimer complex is captured in the middle and right panels.

Figure 5.

Model structures for comparison to SAXS data. (A) Model SAXS curves calculated from the RSV F component of the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle compared with the interpolated 0% D2O SAXS data (Figure S4). The SAXS data were interpolated to a common q spacing to expedite comparison to thousands of model curves. The corresponding vs Rg plots are shown in Figure S5. A representative convergence plot is shown in Figure 6. (B) Ribbon model of a representative prefusion RSV F conformer and the model RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle showing five RSV F trimers anchored by the transmembrane (TM) and cytoplasmic tail (CT) to the cylinder-shaped PS80 core. The glycans and PAM are depicted in CPK. Movie S1 shows representative structures from the five-trimer ensemble. Although a single conformer of each trimer is shown, the flexibility in the p27 and CT regions (Movie S2 and Figures S8 and S9) was explored to confirm that it did not significantly alter the shape of the model SAXS curves. (C) Ribbon model of a representative postfusion RSV F conformer with the extended 6-helical bundle (6HB) and the model RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle showing five RSV F trimers anchored to the central PS80 core structure. The glycans and PAM are depicted in CPK.

The centers of mass of the RSV F trimers were positioned to remain constrained by the fitted length of the cylindrical PS80 component, derived from the SANS data in 41% D2O buffer (Figure S3). The TM and CT regions were positioned within the conformational space of the cylinder representing the PS80 component. This overall structural arrangement is consistent with the TEM images (Figure 2) that show RSV F trimer ectodomain and heads extending outward from an elongated central core. Structure ensembles were generated by rotating the RSV F trimers around the cylinder-shaped PS80 core. Model SAXS data calculated from these ensembles could then be compared directly to the data (Figure 5A). The green points in Figure 5A are interpolated 0% D2O buffer SAXS data as further described in Figure S4. Corresponding vs Rg plots are presented in Figure S5.

The overall shapes of the trimer structures are considerably different. The ectodomain of the prefusion RSV F trimer in Figure 5B is more compact than that of the postfusion RSV F trimer in Figure 5C, while the postfusion RSV F trimer head is more elongated, protruding farther from the PS80 core. In addition, the postfusion F trimer folds into a 6-helical bundle (6HB) near the TM domain, subsequently positioning the p27 domain of the N-terminal F1 subunit closer to the TM domain than in the prefusion RSV F structure. In spite of these shape differences in the RSV F trimers, it was possible to find conformations of the five-trimer models that had Rg values consistent with the SAXS data in both cases. Two different views of five-trimer structures that meet this criterion are shown in the middle and right panels in Figure 5B,C.

Conformational space coverage for the prefusion RSV F five-trimer structure ensemble is illustrated in Figure 6, where the number of unique 5 Å cubic volume pixels (voxels) occupied by an α carbon atom is plotted as a function of the number of structures in the ensemble. The plot indicates that 150 000 voxels are occupied within the first 500 structures. After 1000 structures, 154 000 voxels are occupied and the possibility of finding conformations that would occupy additional voxels is negligible. The convergence plot for the ensemble of postfusion RSV F five-trimer structures is similar. Movie S1 illustrates a subset of the structures in the prefusion RSV F five-trimer ensemble that are present in the density plot and in the SAXS model curves. A given structure in the ensemble was created by choosing a random RSV F trimer unit (2 through 5) and rotating that individual trimer about the long axis of the PS80 core by a random angle.

Figure 6.

Convergence of RSV F/PS80 model in conformation space. Convergence of the ensemble of prefusion RSV F five-trimer structures in conformation space is shown by recording the number of unique 5 Å cubic volume pixels (voxels) occupied by an α carbon atom as a function of the number of structures in the ensemble. As the number of structures increases, the number of new voxels that are occupied decreases and the number of occupied voxels levels off as conformation space is filled. 150 000 voxels are occupied within the first ~500 structures. At 1000 structures, approximately 154 000 voxels are occupied. The corresponding structure density plot showing the region of conformation space covered by the ensemble is shown in Figure S6.

While there is a range of I(q) vs q space covered by each set of model SAXS curves in Figure 5A, the curves fall into two distinct shapes depending on which RSV F trimer was used in the model structure. The region of the data for q ≤ 0.03 Å−1 corresponds to length scales that describe the overall size of the entire nanoparticle, which is also described by Rg. The vs Rg curves in Figure S5 show that the Rg values for the experimental SAXS data can be reproduced not only by a number of single structures but also by structure ensembles, including mixtures of models containing prefusion and postfusion RSV F trimer conformations. Thus, the structures in both ensembles are consistent with the overall size of the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle obtained from the data.

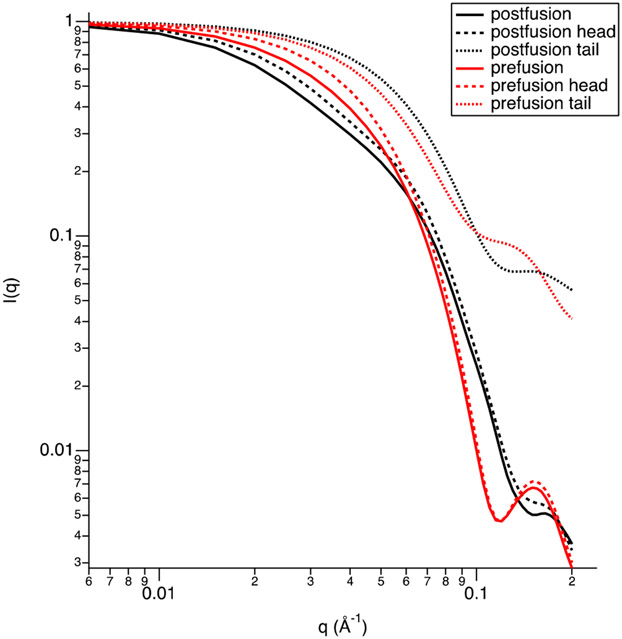

On the other hand, neither ensemble of model SAXS curves contains single structures that agree with the data for q ≥ 0.03 Å−1. Features seen in the data for q ≥ 0.08 Å−1 are more closely related to the shapes of the individual RSV F trimers. This is illustrated in Figure 7, where model SAXS curves from both a prefusion and postfusion RSV F trimer are shown, along with the calculated curves from only the head (ectodomain) and tail (TM and CT) regions.

Figure 7.

RSV F trimer head and tail region scattering curves. Calculated scattering curves for a prefusion and postfusion RSV F trimer (solid curves) compared to those calculated for only the head (residues 1–84 for F2 and 1–399 for F1; dashed curves) and tail (residues 400–455 for F1; dotted curves) regions. The forward scattering has been set to in each case for ease in comparison of the shapes of the curves.

It is evident that the feature seen for q between 0.1 and 0.2 Å−1 in the prefusion RSV F five-trimer model SAXS curves in Figure 5A is also present in the prefusion RSV F single trimer model SAXS curve in Figure 7. Similarly, the shape of the postfusion RSV F five-trimer model SAXS curve for q between 0.1 and 0.2 Å−1 is similar to that for the postfusion RSV F single trimer model SAXS curve. Furthermore, the main contribution to both RSV F single trimer model SAXS curves is from the head region since the shape of the scattering curves for q between ~0.08 and 0.2 Å−1 in Figure 7 is nearly identical for the entire trimer and the head region only.

To illustrate that an ensemble of prefusion and postfusion RSV F five-trimer model curves can be found to fit the data for q ≥ 0.03 Å−1, the 0% D2O SAXS data were fit for q between 0.01 and 0.2 Å−1 to a linear combination of the model curves from the two ensembles shown in Figure 5A. An ensemble of 100 curves was found that fit the data with , as shown in Figure S7. The only fitting parameters were the fractions of each model curve. There was no data-driven bias either on the positions or the orientations of the individual RSV F trimers relative to the PS80 core or on the shapes of the individual RSV F trimers. We note that the satisfactory fit of the SAXS data by an ensemble of prefusion and postfusion conformation does not exclude the possibility of the solution state populated by yet uncharacterized structures, such as those intermediate between these two conformations.

Although the structures in Figure 5B,C show the p27 and CT domains in a single conformation, these regions are flexible, in addition to residues 78–84 in the F2 subunit. Thus, these flexible regions can be in different conformations in each of the RSV F trimers (1–5) in the five-trimer structure. This was not taken into account when creating the structure ensembles. However, the effect of the flexibility in these regions on the model SAXS curves was explored and demonstrated to have a negligible impact on the scattering curves, as shown in Figures S8 and S9.

Figure S8 shows the calculated SAXS curves for ensembles of the prefusion and postfusion RSV F trimer structures in the left panels of Figure 5B,C in which the p27 and CT domains, along with residues 78–84 in the F2 subunit, are flexible. Representative structures from the prefusion RSV F trimer ensemble are shown in Movie S1. There is a range of I(q) vs q space covered by each set of model SAXS curves, but there are two distinct shapes representing the two different RSV F trimer structures. The width of the model SAXS curves reflects the small differences introduced by these flexible regions. Figure S9 shows the model SAXS curves from an ensemble of the prefusion RSV F five-trimer model in Figure 5B, middle and right panels, in which the p27 regions were allowed to be flexible. The flexibility of these regions does not significantly affect the overall shape of the scattering curve.

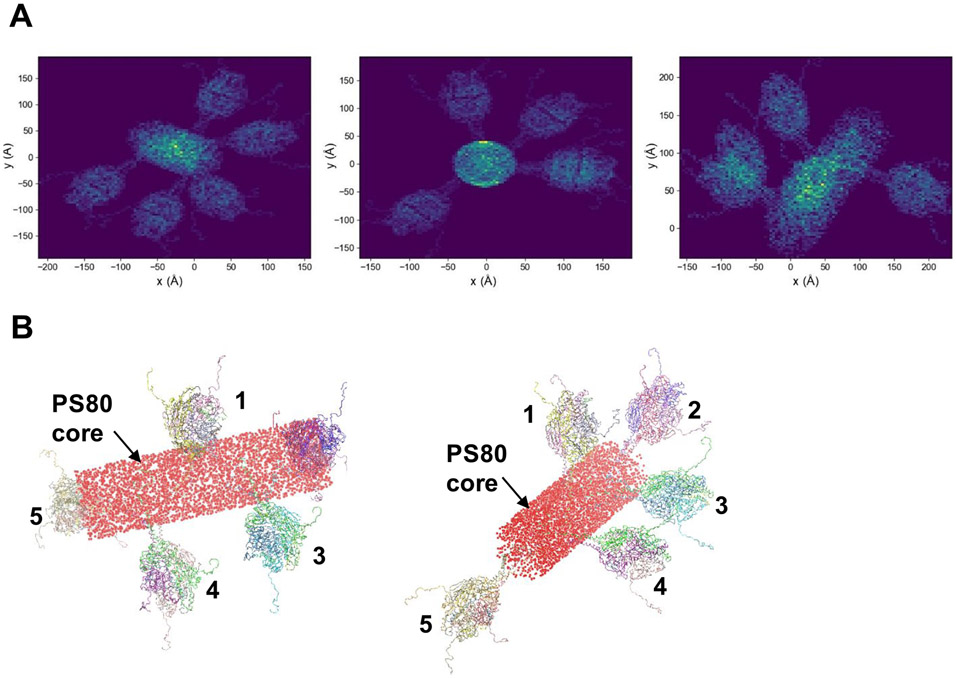

Representative 2D projections of the prefusion RSV F five-trimer model structure are shown in Figure 8A. To reproduce the core intensities seen in the TEM images, the PS80 cylinder volume was filled with spheres (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Two-dimensional (2D) projections of an RSV F five-trimer structure. (A) Representative 2D projections of the RSV F five-trimer model structure consisting of a staggered arrangement of RSV F trimers around the central cylinder-shaped PS80 core, projected at various perspectives onto an plane. (B) RSV F ribbon structures show the arrangement of five RSV F trimers anchored to the PS80 cylinder-shaped core. The cylinder volume is filled with spheres to represent the core density seen in the TEM images.

The projections are consistent with the TEM images. These data suggest that even a single type of nanoparticle containing five RSV F trimers can produce 2D images of nanoparticles that appear to be heterogeneous in the number of RSV F trimers, especially if the nanoparticle is projected along the long axis of the PS80 core.

DISCUSSION

Nanoparticle Self-Assembly and Hydrodynamic Size.

The RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle is a mixed micelle consisting of recombinantly expressed full-length RSV F protein trimers that stably interact with a core of PS80 molecules. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) and sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation (SV-AUC) analysis of the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle provide evidence that nanoparticle size and PS80-to-RSV F molar ratio are correlated. On average, the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle vaccine contains five RSV F trimers and 350 PS80 molecules, with a distribution of nanoparticle species having two to nine RSV F trimers. Based on SAS data for PS80 alone and in complex with RSV F trimers, PS80 micelles adopt a cylindrical shape when they interact with RSV F. Although sample preparation for negative staining TEM can potentially generate structural artifacts, linear chain structures of varying lengths observed in the TEM image in Figure 2A lend support for a mechanism of RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle assembly that involves one-dimensional growth along the long axis of the PS80 core as the number of RSV F trimers embedded in it increases.

Stability of the RSV F/PS80 Nanoparticle.

Colloidal stability of the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle may be related to the dimensions of the PS80 detergent core in the mixed-micelle state and the ability of the detergent core to efficiently shield the transmembrane domains and hydrophobic surfaces of the RSV F trimer from water. AUC data provide experimental evidence that in the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle formulation very few RSV F trimers are free in solution. AUC data in Figure 1D show that increasing PS80 concentration at a fixed concentration of RSV F protein drives the weight-average sedimentation coefficient down to a value of about 8 S, which is consistent with a single RSV F trimer complexed with 70 PS80 molecules. The absorbance signal for species having s20,W ≤ 8 S in the distribution profile in Figure 1E accounts for only about 5% of the total signal. Thus, the AUC data provide experimental evidence that the formation of the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle is energetically favorable and likely driven by hydrophobic interactions between PS80 and the RSV F TM domain. These favorable hydrophobic interactions between fatty acid tails in PS80 and the TM domain of RSV F drive the formation of the nanoparticle and offset the loss of translational entropy during self-assembly.

RSV F/PS80 Nanoparticle Structure.

The data from the solution-based characterization methods (DLS, SV-AUC, and SAS) provide a consistent overall picture of the size and stoichiometry of the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle. The modeling results show that the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle exists in multiple conformations with different rotational arrays of RSV F trimers around the PS80 core and that neither the prefusion nor the postfusion conformation adequately describes the structure of the individual RSV F trimers. The starting structures of RSV F represent conformational snapshots along the virus fusion pathway. RSV F trimers in the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle may have an intermediate conformation or even a distribution of conformations. SAS data cannot distinguish between these possibilities. These structural data are consistent with the recent study demonstrating that the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle vaccine exposes a broad number of important epitopes,18 which more faithfully reflects the native RSV F structure found on infected cells. The modeling presented in this report suggests that RSV F trimers can be interdigitated and can adopt multiple rotameric conformations in the nanoparticle. This arrangement of RSV F antigens around the cylindrical PS80 core may help to stabilize and expose key antigenic sites for development of a robust immune response. Future work should focus on understanding surface density and presentation of the antigen in the micelle since these attributes and accessibility to key epitopes are likely important factors in determining immunogenicity.

CONCLUSIONS

This study highlights SANS in combination with contrast variation as a powerful tool for studying lipid-associated glycoprotein complexes. SANS complements high-resolution X-ray crystallography, which requires the formation of highly ordered arrays of protein–lipid complexes, by providing valuable structural information on the macromolecular complexes that exist in bulk solution. In this study, SANS measurements provided unique information about the structure of the RSV F and PS80 components as they exist in the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle vaccine in solution and allowed the determination of the stoichiometry of the two components. Combining the results from SANS, SAXS, DLS, SV-AUC, and TEM, it was determined that the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle contains on average 350 PS80 molecules, arranged in a cylindrical micellar structure with a radius of 40 ± 5 Å and a length of 280 ± 20 Å, as well as on average five full-length RSV F trimers arranged in an antiparallel conformation along the axis of the cylindrical core. Comparison of ensembles of structures generated for the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle, using all-atom models of full-length RSV F trimers constructed from prefusion and postfusion crystal structures, revealed that the RSV F trimers in the nanoparticle vaccine may exist as a distribution of these conformations or as an intermediate conformation, which can help to explain the broad immunogenic response elicited by the vaccine. The results provide insight into a potential pathway for assembly of the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle vaccine, and the methods used here could enable structural characterization of other lipid–glycoprotein complexes and colloidal vaccine systems.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The SAXS and SANS studies are part of a collaboration between Novavax, Inc. and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), made possible by CRADA (CN-16-0059). Access to the NGB 30 m SANS instrument was provided by the Center for High Resolution Neutron Scattering. Transmission electron microscopy was performed by Nanoimaging Services (San Diego, CA). Analytical ultracentrifugation data for PS80 concentration dependence were generated by Borries Demeler at AUC Solutions, LLC (Houston, TX). Yun Zhang and Elena Bogatcheva are former Novavax employees who performed the Adju-Phos treatment and RP-HPLC testing.

Funding

The Center for High Resolution Neutron Scattering is funded through a partnership between the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the National Science Foundation under Agreement No. DMR-1508249. This work benefitted from CCP-SAS software developed through a joint EPSRC (EP/K039121/1) and NSF (CHE-1265821) grant and from use of the SasView application, originally developed under NSF award DMR-0520547. SasView contains code developed with funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the SINE2020 project, grant agreement No. 654000.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.molpharma-ceut.0c00986.

Amino acid sequence of RSV F used for modeling; PS80 quantitation data for the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle; linear regression data to support determination of partial specific volume of the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle using sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation; D2O contrast parameters and component analysis to derive RSV F/PS80 stoichiometry; essential SAS data acquisition, sample details, data analysis, modeling, fitting, and software used; residuals from P(r) analysis of SANS and SAXS data in Figure 3; SANS data at 41% D2O for the RSV F/PS80 nanoparticle and best-fit cylinder model; Interpolated 0% D2O SAXS data and corresponding vs Rg plots from comparison with prefusion and postfusion models; structure density plot to accompany convergence data presented in Figure 6; ensemble fit of the SAXS data using a combination of model curves from the prefusion and postfusion RSV F five-trimer ensembles from Figure 5A; calculated scattering curves for five-trimer structures with different conformations (PDF)

Movie illustrating a subset of the structures in the prefusion RSV F five-trimer ensemble that are present in the density plot and in the SAXS model curves (Movie S1) (MOV)

Movie showing an RSV F trimer with differing conformations for flexible regions (Movie S2) (MOV)

Certain commercial equipment, instruments, materials, suppliers, or software are identified in this paper to foster understanding. Such identification does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) nor does it imply that the materials or equipment identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

All data associated with this study are available in the main text or the supplemental materials. SANS and SAXS intensity files as well as RSV F trimer and five-trimer model structures are available in the NIST Public Data Repository https://doi.org/10.18434/mds2-2308.

Contributor Information

Susan Krueger, NIST Center for Neutron Research, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, Maryland 20899, United States.

Joseph E. Curtis, NIST Center for Neutron Research, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, Maryland 20899, United States

Daniel R Scott, Novavax, Inc., Gaithersburg, Maryland 20878, United States.

Alexander Grishaev, Institute for Bioscience and Biotechnology Research, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Rockville, Maryland 20850, United States.

Greg Glenn, Novavax, Inc., Gaithersburg, Maryland 20878, United States.

Gale Smith, Novavax, Inc., Gaithersburg, Maryland 20878, United States.

Larry Ellingsworth, Novavax, Inc., Gaithersburg, Maryland 20878, United States.

Oleg Borisov, Novavax, Inc., Gaithersburg, Maryland 20878, United States.

Ernest L. Maynard, Arcellx, Inc., Gaithersburg, Maryland 20878, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Simons K; Helenius A; Leonard K; Sarvas M; Gething MJ Formation of Protein Micelles from Amphiphilic Membrane Proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 1978, 75, 5306–5310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Morein B; Simons K Subunit Vaccines against Enveloped Viruses: Virosomes, Micelles and Other Protein Complexes. Vaccine 1985, 3, 83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Kelly HG; Kent SJ; Wheatley AK Immunological Basis for Enhanced Immunity of Nanoparticle Vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2019, 18, 269–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Irvine DJ; Swartz MA; Szeto GL Engineering Synthetic Vaccines Using Cues from Natural Immunity. Nat. Mater 2013, 12, 978–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Shi T; McAllister DA; O’Brien KL; Simoes EAF; Madhi SA; Gessner BD; Polack FP; Balsells E; Acacio S; Aguayo C; Alassani I; Ali A; Antonio M; Awasthi S; Awori JO; Azziz-Baumgartner E; Baggett HC; Baillie VL; Balmaseda A; Barahona A; Basnet S; Bassat Q; Basualdo W; Bigogo G; Bont L; Breiman RF; Brooks WA; Broor S; Bruce N; Bruden D; Buchy P; Campbell S; Carosone-Link P; Chadha M; Chipeta J; Chou M; Clara W; Cohen C; de Cuellar E; Dang D-A; Dashyandag B; Deloria-Knoll M; Dherani M; Eap T; Ebruke BE; Echavarria M; de Freitas Lázaro Emediato CC; Fasce RA; Feikin DR; Feng L; Gentile A; Gordon A; Goswami D; Goyet S; Groome M; Halasa N; Hirve S; Homaira N; Howie SRC; Jara J; Jroundi I; Kartasasmita CB; Khuri-Bulos N; Kotloff KL; Krishnan A; Libster R; Lopez O; Lucero MG; Lucion F; Lupisan SP; Marcone DN; McCracken JP; Mejia M; Moisi JC; Montgomery JM; Moore DP; Moraleda C; Moyes J; Munywoki P; Mutyara K; Nicol MP; Nokes DJ; Nymadawa P; da Costa Oliveira MT; Oshitani H; Pandey N; Paranhos-Baccalà G; Phillips LN; Picot VS; Rahman M; Rakoto-Andrianarivelo M; Rasmussen ZA; Rath BA; Robinson A; Romero C; Russomando G; Salimi V; Sawatwong P; Scheltema N; Schweiger B; Scott JAG; Seidenberg P; Shen K; Singleton R; Sotomayor V; Strand TA; Sutanto A; Sylla M; Tapia MD; Thamthitiwat S; Thomas ED; Tokarz R; Turner C; Venter M; Waicharoen S; Wang J; Watthanaworawit W; Yoshida L-M; Yu H; Zar HJ; Campbell H; Nair H Global, Regional, and National Disease Burden Estimates of Acute Lower Respiratory Infections Due to Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Young Children in 2015: A Systematic Review and Modelling Study. Lancet 2017, 390, 946–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Shi T; Denouel A; Tietjen AK; Campbell I; Moran E; Li X; Campbell H; Demont C; Nyawanda BO; Chu HY; Stoszek SK; Krishnan A; Openshaw P; Falsey AR; Nair H; Nair H; Campbell H; Shi T; Zhang S; Li Y; Openshaw P; Wedzicha J; Falsey A; Miller M; Beutels P; Bont L; Pollard A; Molero E; Martinon-Torres F; Heikkinen T; Meijer A; Fischer TK; van den Berge M; Giaquinto C; Mikolajczyk R; Hackett J; Cai B; Knirsch C; Leach A; Stoszek SK; Gallichan S; Kieffer A; Demont C; Denouel A; Cheret A; Gavart S; Aerssens J; Fuentes R; Rosen B; RESCEU Investigators. Global Disease Burden Estimates of Respiratory Syncytial Virus–Associated Acute Respiratory Infection in Older Adults in 2015: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Infect. Dis 2019, 222, S570–S576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Johnson S; Oliver C; Prince GA; Hemming VG; Pfarr DS; Wang S; Dormitzer M; O’Grady J; Koenig S; Tamura JK; Woods R; Bansal G; Couchenour D; Tsao E; Hall WC; Young JF Development of a Humanized Monoclonal Antibody (MEDI-493) with Potent In Vitro and In Vivo Activity against Respiratory Syncytial Virus. J. Infect. Dis 1997, 176, 1215–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).The IMpact-RSV Study Group. Palivizumab, a Humanized Respiratory Syncytial Virus Monoclonal Antibody, Reduces Hospitalization From Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection in High-Risk Infants. Pediatrics 1998, 102, 531–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Del Vecchio A; Franco C; Del Vecchio K; Umbaldo A; Capasso L; Raimondi F RSV Prophylaxis in Premature Infants. Minerva Pediatr. 2018, 70, No. 579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Hause AM; Henke DM; Avadhanula V; Shaw CA; Tapia LI; Piedra PA Sequence Variability of the Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Fusion Gene among Contemporary and Historical Genotypes of RSV/A and RSV/B. PLoS One 2017, 12, No. e0175792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Hicks SN; Chaiwatpongsakorn S; Costello HM; McLellan JS; Ray W; Peeples ME Five Residues in the Apical Loop of the Respiratory Syncytial Virus Fusion Protein F 2 Subunit Are Critical for Its Fusion Activity. J. Virol 2018, 92, No. 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).McLellan JS; Chen M; Leung S; Graepel KW; Du X; Yang Y; Zhou T; Baxa U; Yasuda E; Beaumont T; Kumar A; Modjarrad K; Zheng Z; Zhao M; Xia N; Kwong PD; Graham BS Structure of RSV Fusion Glycoprotein Trimer Bound to a Prefusion-Specific Neutralizing Antibody. Science 2013, 340, 1113–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).McLellan JS Neutralizing Epitopes on the Respiratory Syncytial Virus Fusion Glycoprotein. Curr. Opin. Virol 2015, 11, 70–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Swanson KA; Settembre EC; Shaw CA; Dey AK; Rappuoli R; Mandl CW; Dormitzer PR; Carfi A Structural Basis for Immunization with Postfusion Respiratory Syncytial Virus Fusion F Glycoprotein (RSV F) to Elicit High Neutralizing Antibody Titers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2011, 108, 9619–9624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Fuentes S; Coyle EM; Beeler J; Golding H; Khurana S Antigenic Fingerprinting Following Primary RSV Infection in Young Children Identifies Novel Antigenic Sites and Reveals Unlinked Evolution of Human Antibody Repertoires to Fusion and Attachment Glycoproteins. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, No. e1005554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Smith G; Raghunandan R; Wu Y; Liu Y; Massare M; Nathan M; Zhou B; Lu H; Boddapati S; Li J; Flyer D; Glenn G Respiratory Syncytial Virus Fusion Glycoprotein Expressed in Insect Cells Form Protein Nanoparticles That Induce Protective Immunity in Cotton Rats. PLoS One 2012, 7, No. e50852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Gilbert BE; Patel N; Lu H; Liu Y; Guebre-Xabier M; Piedra PA; Glenn G; Ellingsworth L; Smith G Respiratory Syncytial Virus Fusion Nanoparticle Vaccine Immune Responses Target Multiple Neutralizing Epitopes That Contribute to Protection against Wild-Type and Palivizumab-Resistant Mutant Virus Challenge. Vaccine 2018, 36, 8069–8078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Patel N; Massare MJ; Tian J-H; Guebre-Xabier M; Lu H; Zhou H; Maynard E; Scott D; Ellingsworth L; Glenn G; Smith G Respiratory Syncytial Virus Prefusogenic Fusion (F) Protein Nanoparticle Vaccine: Structure, Antigenic Profile, Immunogenicity, and Protection. Vaccine 2019, 37, 6112–6124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Welliver RC; Papin JF; Preno A; Ivanov V; Tian J-H; Lu H; Guebre-Xabier M; Flyer D; Massare MJ; Glenn G; Ellingsworth L; Smith G Maternal Immunization with RSV Fusion Glycoprotein Vaccine and Substantial Protection of Neonatal Baboons against Respiratory Syncytial Virus Pulmonary Challenge. Vaccine 2020, 38, 1258–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Glenn GM; Fries LF; Thomas DN; Smith G; Kpamegan E; Lu H; Flyer D; Jani D; Hickman SP; Piedra PA A Randomized, Blinded, Controlled, Dose-Ranging Study of a Respiratory Syncytial Virus Recombinant Fusion (F) Nanoparticle Vaccine in Healthy Women of Childbearing Age. J. Infect. Dis 2016, 213, 411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).August A; Glenn GM; Kpamegan E; Hickman SP; Jani D; Lu H; Thomas DN; Wen J; Piedra PA; Fries LF A Phase 2 Randomized, Observer-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Dose-Ranging Trial of Aluminum-Adjuvanted Respiratory Syncytial Virus F Particle Vaccine Formulations in Healthy Women of Childbearing Age. Vaccine 2017, 35, 3749–3759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Fries L; Shinde V; Stoddard JJ; Thomas DN; Kpamegan E; Lu H; Smith G; Hickman SP; Piedra P; Glenn GM Immunogenicity and Safety of a Respiratory Syncytial Virus Fusion Protein (RSV F) Nanoparticle Vaccine in Older Adults. Immun. Ageing 2017, 14, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Gilman MSA; Furmanova-Hollenstein P; Pascual G; B. van ‘t Wout A; Langedijk JPM; McLellan JS Transient Opening of Trimeric Prefusion RSV F Proteins. Nat. Commun 2019, 10, No. 2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Hitscherich C; Allaman M; Wiencek J; Kaplan J; Loll PJ Static Light Scattering Studies of OmpF Porin: Implications for Integral Membrane Protein Crystallization. Protein Sci. 2000, 9, 1559–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]