Abstract

The clinical trial conducted in Italy to evaluate the efficacy of acellular pertussis vaccines provided an opportunity to estimate the frequency of clinical infections with Bordetella parapertussis and to compare the clinical characteristics of children suffering from Bordetella pertussis illness with those of children with B. parapertussis illness. This study dealt with 76 B. parapertussis infections diagnosed from a population of 15,601 children participating in the follow-up of suspected cases of pertussis. An overall incidence of 2.1 cases of laboratory-confirmed parapertussis per 1,000 person-years was observed. Children affected by B. parapertussis infections showed a less severe clinical picture both in the duration of symptoms and in the percentage of patients affected, even when compared with vaccinated children with pertussis. To characterize the isolated strains, we performed assays for susceptibility to erythromycin and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and we examined the genomic DNAs by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. The results showed a high degree of genetic stability among B. parapertussis strains regardless of time of collection and geographical distribution.

Whooping cough is mostly associated with Bordetella pertussis infection, but Bordetella parapertussis is also responsible for a whooping cough-like disease (14, 16, 21). The latter generally has a milder clinical presentation (10), but it is not easily distinguished from B. pertussis infection by symptoms, and usually it is not laboratory confirmed. For these reasons the epidemiology of illness caused by B. parapertussis is poorly recognized.

B. pertussis and B. parapertussis share a number of virulence factors, such as filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA), pertactin, tracheal cytotoxin, dermonecrotic toxin, and adenylate cyclase-hemolysin (2, 4, 6, 15, 18). However, the pertussis toxin (PT) is produced only by B. pertussis, since the B. parapertussis toxin gene is not transcriptionally active within the promoter and the coding regions (1). In spite of the similarities, differences in protective epitopes for common antigens and the nonexpression of PT in B. parapertussis may explain the lack of cross-protection between the two species.

During the recent randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted in Italy to evaluate the efficacy of new acellular pertussis vaccines (7), we were also able to estimate the incidence of B. parapertussis infections and to compare the clinical pictures of B. parapertussis and B. pertussis infections.

Furthermore, in order to characterize the isolates of B. parapertussis circulating in our country, we performed susceptibility testing on B. parapertussis isolates and examined the DNA by macrorestriction digestion. Recent studies have demonstrated that the analysis of DNA fragments, generated by rare-cutting restriction enzymes in pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), can be profitably applied to detect the clonal origin and genetic relatedness for Bordetella spp. (11, 22).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients, sampling, and clinical data collection.

A total of 15,601 infants at the age of 2 months were enrolled in the trial between September 1992 and September 1993 and were randomly assigned to four vaccine groups (7). Thirty percent of the infants received a diphtheria-tetanus-whole cell pertussis vaccine (DTPw) manufactured by Connaught Laboratories (Swiftwater, Pa.), 30% received a diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP CB) manufactured by Chiron Biocine (Siena, Italy), 30% received a diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP SB) manufactured by SmithKline Beecham Biologicals (Rixensart, Belgium), and 10% received a diphtheria-tetanus vaccine (DT) manufactured by Chiron Biocine.

Active surveillance of coughing was implemented for all children. Nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPAs) and paired serum samples were collected from children with coughs lasting more than 7 days.

Parents of children with coughs recorded symptoms daily in a standardized diary; a trained nurse contacted the family each week to review and record this information.

The results of the trial (7) indicated that both acellular pertussis vaccines (DTaP CB and DTaP SB) had high clinical efficacy (84%) against pertussis, whereas DTPw showed poor efficacy (36%).

In this study the clinical symptoms of 773 children with B. pertussis infections were compared with those of 76 children with B. parapertussis infections diagnosed during the period September 1992 to September 1995. Sixty-seven B. parapertussis strains isolated from 76 patients with infections were assayed for phenotypic and molecular characteristics.

Laboratory procedures. (i) Culture.

For primary isolation from NPAs, bacteria were grown on charcoal agar plates supplemented with cephalexin (20 μg/ml) (Unipath, Milan, Italy) and incubated at 35°C in a moist atmosphere for 7 days. All suspected colonies were identified by biochemical tests (oxidase, urease) and by agglutination with antisera specific for B. pertussis and B. parapertussis (Murex Diagnostics, Dartford, England) and were confirmed by PCR (23). B. parapertussis ATCC 9305 and B. pertussis ATCC 9797 were used as controls.

(ii) Serology.

Paired capillary blood samples were collected in the acute and convalescent phases from children with coughing episodes. Geometric mean titers of antibodies to PT and FHA were measured by a standardized enzyme-linked immunoassay (17). As in other studies (7, 8, 19, 24), an increase to at least twice the initial value in the level of immunoglobulin G (IgG) or IgA antibody to either PT or FHA was considered significant for the diagnosis of pertussis, provided the intra-assay coefficient of variation was less than 20%.

To discriminate between B. pertussis and B. parapertussis infections when the serological test result was positive only for the common FHA antigen and the relative aspirate was culture negative, a PCR assay for the detection of B. parapertussis DNA in the aspirate was performed by using experimental parameters already described (23, 27).

(iii) Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Assays for susceptibility to erythromycin and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim were performed on B. parapertussis isolates by using the E-test method (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) according to the manufacturer’s package insert.

The MICs were determined after 48-h incubations on charcoal agar plates supplemented with 10% whole defibrinated horse blood (Unipath).

The interpretative criteria were those recommended by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (20). Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 was used as the control strain.

(iv) PFGE.

The chromosomal DNA of each strain of B. parapertussis was prepared according to the method described by Khattak and Matthews (11).

Five DNA plugs of each strain were used for restriction digestion. Each plug slice (2 to 4 mm wide) was suspended in a total volume of 200 μl of restriction buffer and 40 U of XbaI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) and was incubated overnight at 37°C. The same procedure was followed with the restriction enzymes SpeI and DraI. After digestion, the plugs were equilibrated in Tris-EDTA buffer and chilled on ice before loading onto the gel. PFGE was performed with a Chef Mapper II Bio-Rad apparatus.

Digested DNA plugs were electrophoresed in a 1% agarose (Bio-Rad) gel (15 by 15 cm) cast and a 0.5% Tris-borate-EDTA buffer for 27 h at 6.0 V/cm; switching times were ramped from 5 to 45 s, and the included angle was 120°. Lambda ladder PFG markers (New England Biolabs) were added, as molecular size standards, at each run to provide size orientations of the fragments. The gel, stained with 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide/ml for 30 min, was washed with distilled water for 15 min and photographed under UV light. The molecular weights of the restriction bands were determined by the method suggested by Tenover et al. (26).

The degrees of similarity among the isolates were determined by the coefficient of similarity (CS). According to this criterion, a CS between 0.85 and 0.99 indicates closely related isolates, while a CS lower than 0.85 indicates nonrelated isolates (9).

Statistical analyses.

Frequencies of symptoms were compared by the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test. The t test, or the Wilcoxon test, when appropriate, was used for comparing means. Comparison of incidence rates for B. parapertussis infections was performed by using the exact calculation.

RESULTS

Clinical symptoms.

At the end of September 1995, 849 Bordetella sp. infections had been diagnosed, 544 by culture and 305 by serology. In particular, 477 (87.7%) strains were identified as B. pertussis and 67 (12.3%) were identified as B. parapertussis. Two hundred ninety-six B. pertussis infections were diagnosed only by positive serological results, as were 9 B. parapertussis infections; the latter were confirmed by PCR in the aspirate. No case of coinfection was detected.

Children with cultures positive for B. parapertussis were also evaluated for a serological response to the FHA antigen. Thirty-seven percent of them (25 children) were positive for IgG or IgA antibody to FHA, 40% (27 children) were not tested since paired sera were not available, and 23% (15 children) did not reveal a twofold increase in antibody titer. Among all these groups of children, the duration of symptoms did not differ significantly. In particular, for the 15 children with negative serological results, the duration of coughing was 13 to 41 days (mean, 23 days), while those with positive serological results experienced a duration of coughing from 11 to 53 days (mean, 20 days).

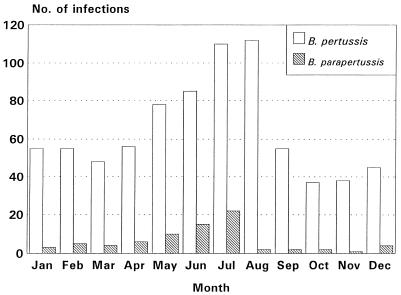

An overall incidence of 2.1 B. parapertussis infections per 1,000 person-years was observed. Of 76 B. parapertussis infections, 51% occurred in males, and the mean age of these children was 15.4 months (range, 2 to 36 months). The two types of infection showed similar seasonal trends, with an increase in cases from April to July, as shown in Fig. 1. The frequencies of symptoms in children with B. parapertussis and B. pertussis infections who had been vaccinated with the DT vaccine or one of the pertussis vaccines are shown in Table 1.

FIG. 1.

Trend of B. pertussis and B. parapertussis infections in Italy by calendar month (September 1992 to September 1995).

TABLE 1.

Frequencies of symptoms of children with B. parapertussis and B. pertussis infections, by vaccine group

| Symptom | No. (%) of B. parapertussis patients (n = 76) | No. (%) of

B. pertussis patients (n = 773)

vaccinated with:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTaP CB (n = 130) | DTaP SB (n = 156) | DTPw (n = 343) | DT (n = 144) | ||

| Cough | 76 (100) | 130 (100) | 156 (100) | 343 (100) | 144 (100) |

| Paroxysm | 58 (76) | 108 (83) | 137 (88) | 317 (92) | 138 (96) |

| Whooping | 25 (33) | 60 (46) | 77 (49) | 233 (68) | 116 (81) |

| Vomiting | 32 (42) | 73 (56) | 97 (62) | 275 (80) | 120 (83) |

| Apnea | 22 (29) | 47 (36) | 77 (49) | 226 (66) | 117 (81) |

| Cyanosis | 9 (12) | 29 (22) | 45 (29) | 159 (46) | 88 (61) |

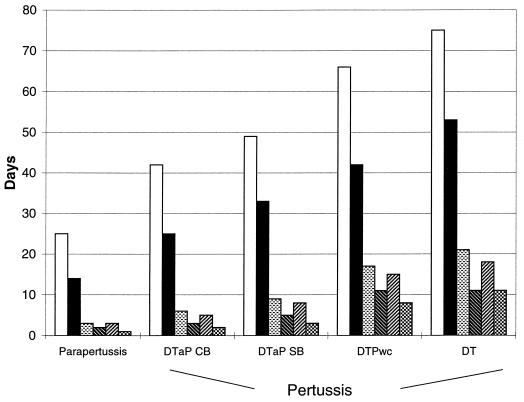

Children with B. parapertussis infections had a significantly lower frequency of all symptoms than all groups of children with B. pertussis infections except the DTaP CB vaccinees. Figure 2 shows the mean duration of symptoms by group. In particular, a significantly shorter duration of coughing (mean duration, 25 days), spasms (14 days), whooping (3 days), and vomiting (2 days) has been observed in children with B. parapertussis infections (P < 0.05). Also, the mean durations of apnea (3 days) and cyanosis (1 day) were shorter in children with B. parapertussis infections than in all groups with B. pertussis infections (P < 0.05) except DTaP CB recipients.

FIG. 2.

Mean durations of symptoms in children with B. parapertussis and B. pertussis infections, by vaccine group. Symbols: □, coughing; ▪, spasms; ░⃞, whooping; , vomiting; ▨, apnea; , cyanosis.

Despite the milder clinical picture observed for children with B. parapertussis infections, it is noteworthy that 25% of them had more than 30 days of coughing and more than 19 days of spasms.

The trend of less severe illness in patients with B. parapertussis is confirmed also by the lower percentage of antibiotic-treated children (6.0%) in the first week of coughing in comparison with those affected by B. pertussis (24%).

Although the clinical trial was not designed to assess the efficacy of the pertussis vaccines in preventing B. parapertussis infections, data show that the incidence of B. parapertussis infection was not significantly different in vaccinated and unvaccinated groups after completion of three doses of vaccine. In particular, we observed an incidence of 0.7 cases of B. parapertussis infections per 1,000 person-years in unvaccinated children (4 cases) compared to incidences of 1.3 in children vaccinated with DTPw (23 cases), 1.0 in DTaP CB recipients (22 cases), and 1.9 in the DTaP SB group (27 cases).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

All B. parapertussis strains were susceptible to erythromycin, the antibiotic of choice for treating whooping cough disease: the MIC at which 90% of the isolates were inhibited (MIC90) was 0.5 μg/ml. Only 2 of the 67 B. parapertussis strains were moderately susceptible to erythromycin, with MICs for the strains being 2 and 3 μg/ml. All the isolates were also susceptible to sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim; the MIC90 was 0.125 μg/ml.

PFGE.

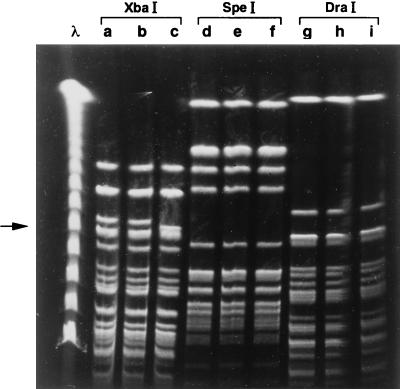

Macrorestriction fingerprinting of the DNAs of the 67 B. parapertussis strains digested with XbaI produced 10 large fragments in the size range from 100 to 500 kb and numerous fragments smaller than 98 kb. These last fragments were not resolved adequately to provide useful information. The comparison of DNA patterns among the strains was based on the variation in the 10 largest fragments.

Two macrorestriction patterns were identified among the 67 isolates, and precisely 57 (85%) had a profile indistinguishable from that of B. parapertussis ATCC 9305 (pattern A), while 10 (15%) had a slightly different profile (pattern A1) characterized by a fragment of 250 kb instead of the 262-kb fragment present in pattern-A strains (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

PFGE profiles of B. parapertussis NPAs digested with three different restriction enzymes, as shown. Lane λ, lambda ladder molecular-size markers (New England Biolabs); lanes a, d, and g, B. parapertussis ATCC 9305 DNA; lanes b, e, and h, B. parapertussis DNA with profile indistinguishable from that of B. parapertussis ATCC 9305 (pattern A); lane c, B. parapertussis DNA with profile slightly different (pattern A1) from that of B. parapertussis ATCC 9305 after digestion with XbaI (arrow indicates the presence of a different band, of approximately 250 kb); lanes f and i, B. parapertussis DNA representative of pattern A1 digested by SpeI and DraI, respectively.

The same isolates, when examined with the restriction enzymes SpeI and DraI, showed identical patterns which could not be distinguished from that of the reference strain.

The CS calculated between patterns A and A1 was 0.9. No correlation was found between patterns and duration of coughing or severity of illness (paroxysms, etc.).

The circulation of pattern A1 in the regions participating in the clinical trial seemed to be limited to the northern regions, since it was not present in the southern region of Puglia.

DISCUSSION

The great interest that for years has been devoted to the whooping cough disease caused by B. pertussis has led to less attention to the closely related species B. parapertussis. The latter is also responsible for outbreaks of whooping cough-like disease in children, although it has been shown that clinical symptoms are generally milder (10).

In spite of the high degree of homology shown by the amino acid sequences of the main antigens, the two species differ with respect to several protective epitopes. In fact, antipertussis vaccines in an animal model (12) and even B. pertussis infections (25) do not seem to protect against B. parapertussis infections.

Assuming that pertussis vaccines are not efficacious in preventing B. parapertussis infections, as suggested also by this study, the incidence of B. parapertussis infection in Italian children 36 months of age or younger is 2.1 per 1,000 person-years. This figure does not, however, include asymptomatic cases or those with coughing lasting fewer than 7 days. Moreover, given the significant clinical picture observed, all the cases studied may be considered infections, even those in which serological responses were negative.

The analysis of clinical characteristics for children with B. parapertussis infections shows that the cough is accompanied by paroxysms in 76% of the cases and by posttussive vomiting in nearly 40%. However, the duration of the symptoms is significantly shorter for B. parapertussis infections than for B. pertussis infections in both vaccinated and unvaccinated children.

The similarity of symptoms observed in the comparison between B. parapertussis infections in all patients and B. pertussis infections in DTaP CB vaccinees points out the potential for clinical misdiagnosis in children vaccinated against pertussis. In this respect, PCR may be a valuable tool for differentiating Bordetella spp. in those cases where the only positive result is the serological response to the common FHA antigen.

No children had evidence of coinfection by B. parapertussis and B. pertussis during the period considered for the comparison of the clinical symptoms, suggesting that such an event is not frequent.

The low MIC90s of erythromycin and sulfamethoxazole-trimethroprim support their continued use for therapy and prophylaxis, respectively (3, 5, 13). The stability of the effectiveness of these antimicrobial agents over time might be ascribed to the low frequency of genetic transformation in the natural population of Bordetella spp.

The clonal structure of B. parapertussis is also confirmed by the results of the DNA macrorestriction digests by PFGE in the strains examined in this study. In fact, the macrorestriction pattern obtained by XbaI digestion in 85% of B. parapertussis strains examined could not be distinguished from that obtained with the B. parapertussis ATCC 9305 reference strain, while the remaining 15% of the strains examined had a profile which differed by only two fragments. All the isolates had identical DNA patterns following digestion with two other restriction enzymes. The CS between the two patterns was 0.9, confirming they were closely related.

The slight difference may be attributed to a single genetic event, such as the deletion of the 12-kb fragment from the 262-kb fragment or a point mutation, creating a new chromosomal restriction site for XbaI.

Although B. parapertussis infection appears to have a lower incidence and a milder clinical picture than B. pertussis infection, its role should not be minimized, particularly in communities where most children are vaccinated against pertussis, since these vaccines do not seem to protect against B. parapertussis.

In the future, a more accurate knowledge of the epidemiology of B. parapertussis infections and of the protective antigens of the microorganism will permit the development of an appropriate prophylaxis, which antipertussis vaccines do not seem to provide.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partly supported by a contract (A.I. 25138) with the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

We thank David L. Klein, H. Bogaerts, and R. Rappuoli for critical reading of the manuscript. T. Sofia is thanked for his support and editorial assistance during the preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aricò B, Rappuoli R. Bordetella parapertussis and Bordetella bronchisepticacontain transcriptionally silent pertussis toxin genes. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2847–2853. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2847-2853.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blom J, Hansen G A, Poulsen F M. Morphology of cells and hemagglutinogens of Bordetella species: resolution of substructural units in fimbriae of Bordetella pertussis. Infect Immun. 1983;42:308–317. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.1.308-317.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boss J W. Erythromycin for treatment and prevention of pertussis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1986;5:154–157. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198601000-00051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cookson B T, Goldman W E. Tracheal cytotoxin: a conserved virulence determinant of all Bordetellaspecies. J Cell Biochem. 1987;11B:124. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cullen A S, Cullen H B. Whooping-cough: prophylaxis with cotrimoxazole. Lancet. 1978;i:556. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Endoh M, Takezawa T, Nakase Y. Adenylate cyclase activity of Bordetellaorganisms. Its production in liquid medium. Microbiol Immunol. 1980;24:95–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1980.tb00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greco D, Salmaso S, Mastrantonio P, Giuliano M, Tozzi A, Anemona A, Ciofi degli Atti M, Giammanco A, Panei P, Blackwelder W C, Klein D L, Wassilak S G F The Progetto Pertosse Working Group. A controlled trial of two acellular vaccines and one whole-cell vaccine against pertussis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:341–348. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602083340601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gustafson L, Hallander H, Olin P, Reizenstein E, Storsaeter J. A controlled trial of a two-component acellular, a five-component acellular, and a whole-cell pertussis vaccine. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:349–355. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602083340602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartstein A I, Chetchotisakd P, Phelps C L, LeMonte A M. Typing of sequential bacterial isolates by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;22:309–314. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(95)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heininger U, Klemens S, Schmitt-Grohé S, Lorenz C, Rost R, Christenson P, Uberall M, Cherry J D. Clinical characteristics of Bordetella parapertussis compared with illness caused by Bordetella pertussis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:306–309. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199404000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khattak M N, Matthews R C. Genetic relatedness of Bordetellaspecies as determined by macrorestriction digests resolved by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:659–664. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-4-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khelef N, Danve B, Quentin-Millet M J, Guiso N. Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis: two immunologically distinct species. Infect Immun. 1993;61:486–490. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.486-490.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurzynski T A, Boehm D M, Rott-Petri J A, Schell R F, Allison P E. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Bordetellaspecies isolated in a multicenter pertussis surveillance project. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:137–140. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.1.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lautrop H. Epidemics of Bordetella parapertussis: 20 years’ observations in Denmark. Lancet. 1971;i:1995–1998. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)91713-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L J, Dougan P, Novotny P, Charles I G. P70 pertactin, an outer membrane protein from Bordetella parapertussis: cloning, nucleotide sequence and surface expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:409–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linneman C C, Perry E B. Bordetella parapertussis: recent experience and a review of the literature. Am J Dis Child. 1977;131:560–563. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1977.02120180074014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manclark C R, Meade B D, Burstyn D G. Serological response to Bordetella pertussis. In: Rose N R, Friedman H, Fahey J L, editors. Manual of clinical laboratory immunology. 3rd ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1986. pp. 388–394. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mooi F R, van der Heide H G J, TerAvest A R, Welinder K G, Livey I, van der Zeisj B M A, Gaastra W. Characterization of fimbrial subunits from Bordetellaspecies. Microb Pathog. 1987;3:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Müller F-M C, Hoppe J E, Wirsing von König C-H. Laboratory diagnosis of pertussis: state of the art in 1997. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2435–2443. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2435-2443.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A2. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novotny P. Pathogenesis in Bordetellaspecies. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:581–582. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.3.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porter J F, Connor K, Donachie W. Differentiation between human and ovine isolates of Bordetella parapertussisusing pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;135:130–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb07977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stefanelli P, Giuliano M, Bottone M, Spigaglia P, Mastrantonio P. Polymerase chain reaction for the identification of Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;24:197–200. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(96)00064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Storsaeter J, Hallander H, Farrington C P, Olin P, Mollby R, Miller E. Secondary analyses of the efficacy of two acellular pertussis vaccines evaluated in a Swedish phase III trial. Vaccine. 1990;8:457–461. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(90)90246-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taranger J, Trolfors B, Lagergard T, Zackrisson G. Parapertussis infection followed by pertussis infection. Lancet. 1994;344:1703. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90485-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Zee A, Agterberg C, van Agterveld M, Peeters M, Mooi F R. Characterization of IS1001, an insertion sequence element of Bordetella parapertussis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:141–147. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.141-147.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]