Abstract

Significance:

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) leads to a significant burden of morbidity and impaired quality of life globally. Diabetes is a significant risk factor accelerating the development of PAD with an associated increase in the risk of chronic wounds, tissue, and limb loss. Various magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques are being increasingly acknowledged as useful methods of accurately assessing PAD.

Recent Advances:

Conventionally utilized MRI techniques for assessing macrovascular disease have included contrast enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), noncontrast time of flight MRA, and phase contrast MRI, but have significant limitations. In recent years, novel noncontrast MRI methods assessing skeletal muscle perfusion and metabolism such as arterial spin labeling (ASL), blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) imaging, and chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) have emerged.

Critical Issues:

Conventional non-MRI (such as ankle-brachial index, arterial duplex ultrasonography, and computed tomographic angiography) and MRI based modalities image the macrovasculature. The underlying mechanisms of PAD that result in clinical manifestations are, however, complex, and imaging modalities that can assess the interaction between impaired blood flow, microvascular tissue perfusion, and muscular metabolism are necessary.

Future Directions:

Further development and clinical validation of noncontrast MRI methods assessing skeletal muscle perfusion and metabolism, such as ASL, BOLD, CEST, intravoxel incoherent motion microperfusion, and techniques that assess plaque composition, are advancing this field. These modalities can provide useful prognostic data and help in reliable surveillance of outcomes after interventions.

Keywords: peripheral arterial disease, noncontrast magnetic resonance angiography, dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging, quiescent-interval single-shot, blood-oxygen-level dependent imaging, arterial spin labeling

Christopher M. Kramer, MD

SCOPE AND SIGNIFICANCE

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) leads to a significant burden of morbidity and impaired quality of life, with an estimated prevalence of 5.8–10% among adults over 40 in the United States and over 200 million affected globally.1 Diabetes is a significant risk factor accelerating the development of PAD, with an estimated increased risk of 40–80%2,3 and an associated increase in the risk of chronic wounds, tissue/limb loss.4 Early diagnosis and initiation of appropriate therapeutic measures is key.

This review aims to describe conventional and novel MRI modalities that are gaining popularity and not only detect macrovascular stenosis but also aid in the elucidation of the complex interactions between flow-limiting lesions, microvascular perfusion, and muscular metabolism.

TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE

MRI techniques have improved the understanding of various molecular and structural factors involved in lower extremity (LE) perfusion and angiogenic responses involved in reperfusion. For example, Greve et al., used skeletal muscle oxygenation assessed by blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) MRI to show that the inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEG-F) hindered angiogenesis in a mouse model.5 The same investigators then showed that recombinant murine VEG-F improved angiogenesis as assessed by increased collateral vessel formation on time-of-flight (TOF) magnetic resonance angiography (MRA).6 Further utilization of these and other MRI techniques described in this review at a translational level may help in the development of additional therapeutics for PAD.

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

Commonly used diagnostic imaging modalities for assessing PAD include the ankle-brachial index (ABI), duplex ultrasonography (DUS), and computed tomographic angiography (CTA). Although these are well validated, and have acceptable sensitivities and specificities, they are associated with significant limitations. ABI can be limited by noncompressible arteries particularly in diabetic patients,7 DUS is limited in its assessment of more proximal iliac vessels by artifacts, bowel gas, or arterial calcifications,8 and assessment of stenosis by CTA may be hindered by artifact due to severe calcifications.9 In this setting, MRI techniques can be advantageous, although historically less popular in the field of PAD diagnostics or surveillance.

The sensitivity and specificity of contrast enhanced MRA has been reported to be above 95%. Several noncontrast MRA techniques, such as TOF-MRA, phase contrast MRA (PC-MRA), balanced steady-state free precession MRA (b-SSFP), quiescent-interval single-shot (QISS) MRA, also provide robust anatomic assessment, although limited by flow dependency and diagnostic quality.10

The mechanisms of PAD are complex, and there is growing interest in the assessment of skeletal muscle perfusion, microvascular hemodynamics and muscular metabolism, and energetics for the early diagnosis of PAD, determining response to an intervention, serving as endpoints for clinical trials, and providing prognostic information. Although currently largely limited to research, MRI techniques such as first-pass gadolinium enhanced perfusion imaging, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, BOLD, arterial spin labeling (ASL), chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST), and intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) MRI have shown utility in this regard.11

MRI BASED IMAGING MODALITIES IN PAD

A variety of MRI techniques are available for assessing PAD. MRA, which can be performed using contrast enhanced or noncontrast enhanced methods, focuses on the anatomic assessment of macrovascular stenosis/occlusion of peripheral arteries. Another group of MRI techniques, which are presently limited to the research setting, are those that provide a more functional assessment of skeletal muscle perfusion, energetics, and metabolism and assess the interaction between macrovascular stenosis and skeletal muscle which results in the symptoms of PAD or improvement after interventions. We review each of these in further detail below.

Contrast-enhanced MRA

Currently, the most common clinically utilized MRA modality is contrast-enhanced MRA (CE-MRA). Image acquisition in CE-MRA is based on the increase in arterial signal after administration of intravenous paramagnetic gadolinium based contrast. Since this was first introduced in clinical studies in the mid-1990s, there have been significant improvements in technique that have allowed improved spatial resolution, with reduced acquisition times, resulting in high resolution 3D time-resolved studies.12

Optimal acquisition requires planning. Initially, localizer images are obtained of the arterial tree in axial planes and reviewed to ensure that all regions of interest of the arterial tree are included. Since contrast agent circulation can be affected by rate and volume of contrast injection, and the patient's cardiac output, real-time bolus monitoring software (now standard on all major MRI system vendors) determines (or allows the operator to determine) when appropriate signal enhancement in the arterial bed of interest is achieved and then proceeds with image acquisition. Mask subtraction removes background signal before image analysis to enhance visualization of the vasculature12,13 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography of the lower extremity vasculature in a patient with PAD. PAD, peripheral arterial disease.

CE-MRA is a well validated noninvasive method of PAD evaluation and preprocedural planning. A meta-analysis showed that 3D CE-MRA was highly accurate for detection of LE PAD with a stenosis of >50%, with an estimated point of equal sensitivity and specificity at 94% compared to the gold standard of invasive contrast angiography or digital subtraction angiography (DSA).13,14 In a randomized trial conducted by de Vries et al., the use of CE-MRA over standard DUS for initial work-up of PAD was found to reduce the number of additional imaging procedures by 42%, with no difference in total cost.15 Although data are limited regarding the use of CE-MRA specifically in the diabetic population, CE-MRA was reported to have a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 86% and 83%, respectively, in one meta-analysis.16

Although CE-MRA has some drawbacks, a variety of advances have also emerged in response. Venous enhancement in the lower leg can reduce the accuracy of assessing arterial vasculature. This is particularly problematic in patients with cellulitis, chronic limb ischemia, or in AV malformations, all of which are more prevalent in diabetics, due to inflammation resulting in faster arterio-venous transit time of contrast. Various methods have been used to overcome this, including faster acquisition speeds using multielement surface coils and parallel imaging with multiple reception coils and “hybrid” dual-injection imaging protocols in which the lower legs are imaged first, followed by the upper legs in a separate acquisition in a time-resolved manner.13,17

The potential risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) in patients with stage IV and V chronic kidney disease (CKD), with the administration of gadolinium based contrast agents (GBCAs), is another issue that is often raised, also pertinent among diabetics who are at an elevated risk of CKD. A recent meta-analysis found that the incidence of NSF with macrocyclic GBCAs was <0.07% and that the diagnostic harms of withholding clinically indicated MRIs/MRAs in these patients likely outweighed risks.18 This was adopted in recent recommendations from the American College of Radiology.19 Overall, the incidence of NSF overall has declined dramatically over the past decade, and contemporary practice with the predominant use of macrocyclic GBCAs has rendered the risk of NSF as nearly nonexistent.

Noncontrast MRA

Although CE-MRA is widely used and considered an accurate method of assessing the peripheral vasculature, noncontrast MRA (NC-MRA) techniques have their own advantages and remain relevant. These techniques avoid the use of contrast agents and associated paraphernalia, which by some estimates can result in significant cost savings although slightly offset by increased scan times.20 Issues with mistiming of the scan with respect to the contrast bolus or the potential for nondiagnostic scans due to patient motion on first-pass imaging are also eliminated with NC-MRA. Finally, although NSF with current macrocyclic GBCAs is less of a concern, institutional guidelines in this regard still vary and some clinicians remain hesitant to obtain CE-MRAs in patients with advanced CKD.20,21 There are also reported concerns regarding long-term deposition in the brain and bones, although these have not been well elucidated.22,23

Time of flight MRA

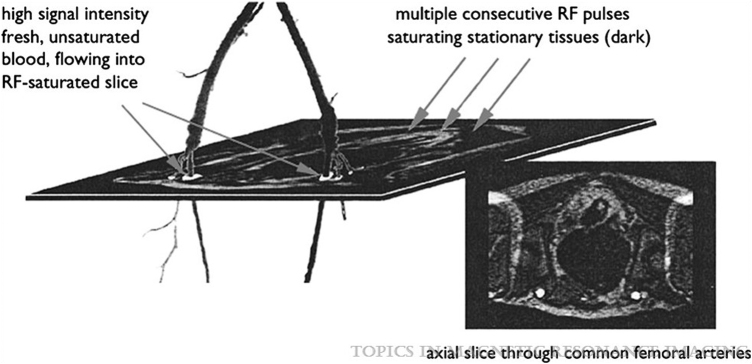

Time of flight MRA is the oldest NC-MRA technique and is currently still the most widely used, in vascular beds other than the LE. The “contrast” in the final image acquired is generated based on the principle of flow related enhancement. The stationary background tissue is saturated (such that it acquires a low signal intensity) by repetitive radiofrequency (RF) pulses, so when fresh unsaturated blood flows in, it is seen in the imaged slice as an area of high signal intensity24 (Fig. 2). Vascular signal intensity depends on the amount of unsaturated blood in the slice at the time of sampling, which in turn depends on blood velocity, the thickness of the imaging slice, and the time between applied RF pulses.

Figure 2.

Principle of TOF-MRA in a healthy patient. Reprinted from Leiner13 with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health. TOF-MRA, time of flight magnetic resonance angiography.

Therefore, although this is an attractive noncontrast method in theory, it is associated with several challenges, particularly for imaging LE vasculature. It requires long acquisition times, vascular signal loss may occur with slower flow or retrograde flow to which PAD patients are prone, and artifacts inherent to this method (partial saturation effects related to in-plane flow and flow-related turbulence, patient motion) can overestimate the degree and length of stenoses.13,21 Although methods to reduce acquisition times compressed sensing and parallel imaging techniques are being studied,25 TOF-MRA is not commonly used clinically for LE PAD, but remains in use for evaluation of intracranial and extracranial arteries.

Phase contrast MRA

Phase-contrast MRA was one of the first MRA techniques used for imaging peripheral arteries, first described in 1985.26 The contrast between vessel and background tissue in this method is based on the fact that when opposite (bipolar) magnetic gradients are applied to an imaging plane in succession, protons in stationary tissue have no net phase shift, whereas protons in moving blood do have a phase shift determined by their velocity and direction. Subtracting the two datasets then generates an image of the arterial tree.13,21 Severity of peripheral artery stenosis estimated by PC-MRA in PAD patients has shown to correlate well to stenosis severity determined by DSA.27

This technique is severely limited by low spatial resolution with signal losses caused by turbulence and vessel tortuosity, and long scan times, limiting its practical use in assessment of PAD.13,21 As a result, although it showed promise for use as complimentary screening modality to DUS, for preprocedural planning and postprocedural follow-up, its contemporary use remains limited.

Quiescent-interval single-shot MRA

Quiescent-interval single-shot MRA is a relatively new technique that is cardiac-gated and specifically caters to peripheral artery imaging. When the R wave is detected on the EKG marking early systole, two successive RF pulses are applied to the imaging plane, one to saturate and suppress signal from stationary background tissue and the second to suppress venous signal, followed by a quiescent interval (230–280 ms) corresponding to systole during which fully magnetized, unsaturated arterial blood flows into the imaging plane. After an additional RF pulse to suppress fat, which can also appear bright, a bSSFP readout image is acquired during diastole, effectively imaging a single slice in each heartbeat. This is then repeated to cover the area of interest20,21 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

QISS noncontrast magnetic resonance angiography. Examples of arteriogram (A) and venogram (B) in a healthy patient. Reprinted from Cavallo et al.21 with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health. QISS, quiescent-interval single-shot.

QISS-MRA has several advantages. Due to the quiescent interval corresponding to systole, loss of signal from inflowing arterial blood is less likely and it is therefore effective in low-flow situations common in the lower extremities with PAD. It is relatively rapid and can acquire images from the pelvis to the ankles in ∼7 min. Patient motion-related artifacts are also more avoidable due to shorter scan times that allow several slices to be acquired in the duration of a single breath-hold.20,21

A variant ungated QISS method has been developed which allows for imaging patients with arrhythmias.28 In diabetics, QISS avoids image artifacts from small vessel calcifications that CTA is prone to.29 Some limitations due to the use of bSSFP as the readout method include lower resolution multiplanar reconstructions in the superior-inferior direction due to limited slice thickness (2–3 mm) and the occurrence of off-resonance artifacts from metallic implants or air-filled bowel loops.21 A variant technique called thin-slab stack-of-stars 3D QISS-MRA has been described, which reduced slice thickness and improved resolution for smaller caliber vessels.30

This is a well validated NC MRA technique for the assessment of PAD and has demonstrated a high median sensitivity and specificity of 90% and 96%, respectively, for detection of ≥50% stenoses compared to DSA and CE-MRA across multiple studies.21 At 3 Tesla, the sensitivity and specificity for QISS with respect to DSA and CE-MRA increase.21 QISS MRA has also specifically been studied for PAD in diabetic populations and has similarly shown a sensitivity of ∼89% and specificity of ∼93% for detection of ≥50% stenoses compared to CE-MRA.29 Studies have also compared this technique to DSA in diabetics with and without critical limb ischemia where it has also performed reasonably well for detection of hemodynamically significant stenoses.31,32 It has been shown to be a reliable method for preprocedural lesion assessment and estimation of stent dimension.33

Overall, QISS has established itself as a valuable noncontrast MRA modality for imaging peripheral vasculature, in a broad population, including diabetics. Ongoing technical advances may render it a useful diagnostic tool for a wide range of vascular disorders.34

Three-dimensional fast spin echo MRA

Three-dimensional Fast Spin Echo MRA (FSE-MRA) is a cardiac-gated sequence. During systole, arterial blood contributes no signal as it flows out of the imaging plane but slow venous blood and stationary tissue contribute signal. During diastole when arterial flow is slower, the entire imaging plane contributes signal. Throughout the cardiac cycle a sequence of RF pulses is applied. The systolic image is then subtracted from the diastolic image to depict the arterial tree21,35 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional fast spin echo magnetic resonance angiography of the foot, coronal (A) and coronal sagittal image rotated 6 degrees (B). Reprinted from Edelman et al.34 with permission from the Radiological Society of North America.

Studies have shown that FSE-MRA has a sensitivity ranging from 79% to 85% and negative predictive value of 92% for detecting significant stenoses compared to CE-MRA.36,37 Compared to CTA, studies have demonstrated variable sensitivity ranging from 76% to 97% and negative predictive value of 90–99%, with investigators postulating its potential use as a safe, noninvasive screening test.38,39 It is, however, subject to artifacts related to subtraction, motion, and inaccurate timing of the systolic and diastolic acquisitions. In comparison to QISS-MRA, studies have shown that it has equivalent diagnostic accuracy in patients with intermittent claudication although with lower reader confidence,40 while it appears inferior to QISS-MRA in patients with critical limb ischemia.41 This technique is useful in visualizing the arterial wall, with good correlation to CE-MRA, and is less prone to artifacts from metallic stents/prostheses compared to QISS-MRA.41

Flow-sensitive dephasing magnetization preparation MRA

The flow sensitive dephasing (FSD) MRA technique is similar to FSE-MRA in that it is cardiac-gated and a subtractive imaging method. Instead of a fast-spin echo readout format, bSSFP is used. While in FSE MRA, the FSE readout images themselves differentiate systolic (dark artery) and diastolic images (bright artery) which are then subtracted to visualize the arterial tree, here, a specific sequence of RF pulses called the FSD prepulse is applied in systole to obtain dark artery images in a flow-sensitive manner. This method provides greater resolution than FSE MRA, with improved signal-noise and contrast-noise ratio. Its limitations are overall similar to that of FSE MRA and requires longer acquisition times compared to QISS, making it less useful in noncompliant patients.20,21

Studies have demonstrated good sensitivities (ranging from 82% to 100%) and specificities (ranging from 91% to 98%) compared to CE-MRA and DSA for detecting hemodynamically significant stenoses in the calf.21 This technique has been specifically studied in diabetics. In a study comparing FSD MRA to CE-MRA in diabetics undergoing evaluation of pedal arteries, FSD MRA yielded a high percentage of diagnostic arterial segments, with an average sensitivity and specificity of 88% and 93%.42 Zhang et al., compared FSD and QISS MRA in diabetic patients and found that both had a similar sensitivity and negative predictive value compared to CE-MRA, with FSD showing a slightly higher specificity attributed to its submillimeter spatial resolution. Although this technique is not commercially available, it has the potential to be a reliable screening tool particularly for assessment of distal LE arteries.26

Velocity-selective MRA

Velocity-selective MRA (VS-MRA) is a recently developed cardiac-gated NC-MRA method. Similar to the method used in FSD MRA, here, a specific sequence of RF pulses called the VS prepulse is applied at peak systole that excites protons in flowing and not stationary blood, thereby suppressing signal from background tissue and venous flow while simultaneously preserving arterial blood signal (Fig. 5). Balanced SSFP readouts are used, similar to FSD MRA, which further enhances the arterial signal. It is a nonsubtractive method which reduces the scan time and limits the potential for motion artifact. Systolic image acquisition makes it less sensitive to arrhythmias.21,43

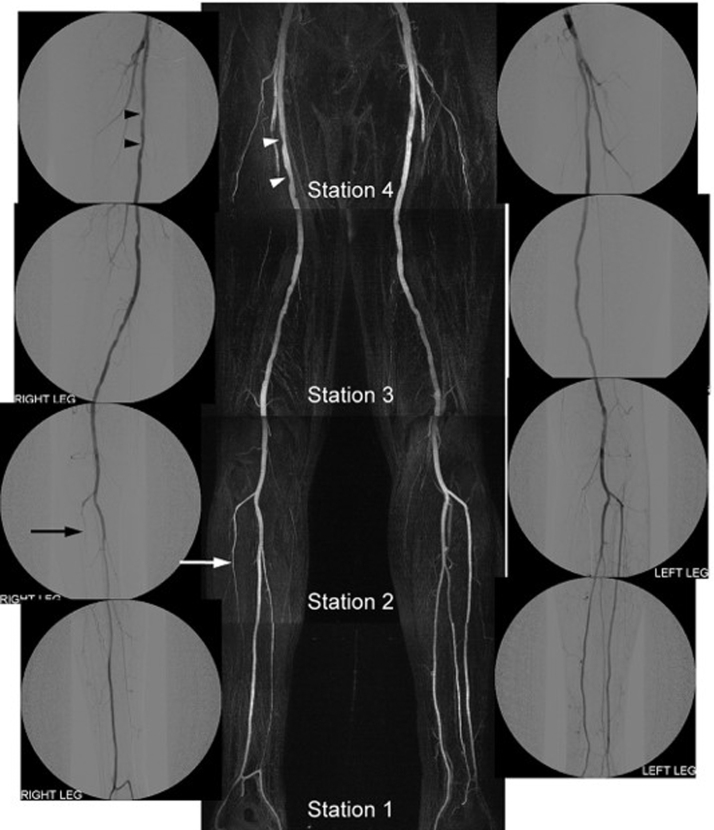

Figure 5.

Velocity-selective magnetic resonance angiography and DSA images in a patient with mild right sided claudication. The MR angiogram shows excellent agreement with the DSA image in identifying mild intermittent narrowing in the right femoral artery (arrowheads) and occlusion of the right anterior tibial artery (arrow). Reprinted from Shin et al.44 with permission from John Wiley and Sons. DSA, digital subtraction angiography.

When tested against DSA in PAD patients, it demonstrated a sensitivity range of 75–85% and specificity range of 94–97% with a high image quality score.44 This technique is not clinically available and requires further validation against noninvasive CE- and NC-MRA techniques, but remains promising for assessment of LE PAD.

MRI methods of assessing skeletal muscle perfusion and energetics

The methods discussed thus far focus primarily on identifying anatomic stenoses/occlusion or alterations in bulk flow in peripheral arteries. The pathophysiology of PAD, however, is complex and incompletely understood, particularly with regards to skeletal muscle perfusion and metabolism/energetics. This need has driven the development of novel techniques that can help clarify pathophysiologic mechanisms and serve as diagnostic tools and as accurate methods of assessing clinical outcomes in PAD. The recently developed techniques discussed in this section are predominantly noncontrast MRI techniques or hybrid approaches geared toward the above.

Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI

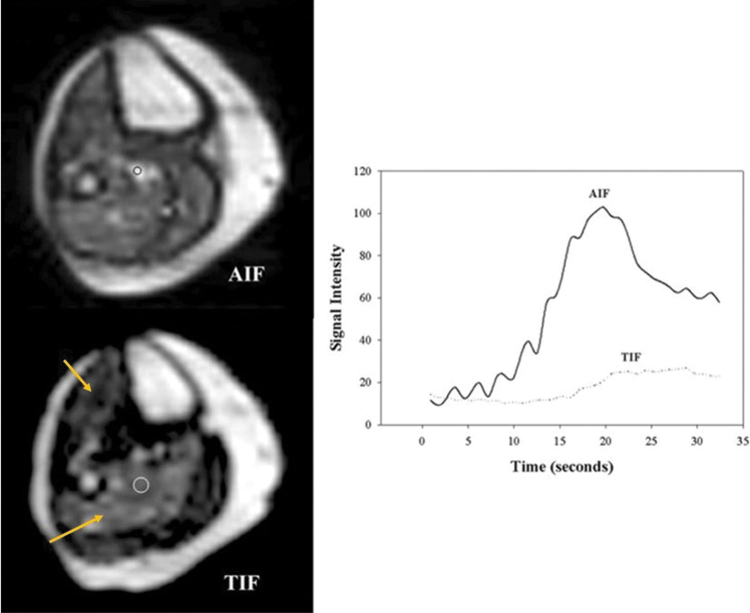

Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) has been validated for assessment of myocardial perfusion and has been adapted to assessing skeletal muscle perfusion. It is performed using a T1-weighted sequence to visualize a GBCA in transit through tissue. Signal intensity changes in the muscle parallel to contrast administration and time intensity curves can be generated, the upslope of which correlates well with gold standard invasive measures of microsphere blood flow (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Quantitative analysis of dynamic first-pass contrast-enhanced calf muscle perfusion at peak exercise. Axial spin-recovery (left upper panel) and inversion-recovery (left lower panel) images during contrast infusion at the level of the mid-calf with regions of interest drawn. Note regional enhancement in the anterior tibialis and soleus muscle regions (arrows, lower left panel). Time-intensity curves (right) from the soleus and the labeled artery (circle, left lower panel) are shown. AIF, arterial input function; TIF, tissue input function.

Peak-exercise (performed with a plantar flexion ergometer) measurement of lower limb perfusion with dynamic first pass contrast enhanced MRI was able to diagnose mild-moderate PAD and correlated to the 6-min walk test.11,45 A DCE-MRI protocol using lower dose GBCAs and measuring perfusion at low-intensity and exhaustive exercise in the same session showed that this technique was feasible for quantifying exercise-induced hyperemia, a promising functional test for PAD.46 It has been hypothesized that this type of protocol might allow for an MRA to detect macrovascular stenoses and DCE-MRI to interpret muscle perfusion distribution on the same day which can then better guide plans for revascularization.46 This is a method that remains in the research realm, yet shows promise for being adopted into clinical practice.

Arterial spin labeling

ASL is a noncontrast method capable of measuring microvascular flow in a spatially and temporally resolved manner. In this technique, blood is used as an endogenous tracer by ‘labeling’ or tagging protons in inflowing blood using RF pulses. Two scans are obtained, with and without tagging of arterial blood. Blood flow is then quantified from the signal difference between tagged and untagged images47,48 (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Pulsed arterial spin-labeling of a calf in a patient with peripheral arterial disease after peak exercise showing increased flow in the anterior tibialis and peroneus longus muscles (black arrows).

Perfusion measured by ASL is highly reproducible during exercise and low blood flow states and agrees closely with invasive measures of perfusion.47 Both continuous and pulsed ASL methods have demonstrated the ability to accurately diagnose PAD and correlate well with the extent of disease as determined by ABI.48,49 Perfusion can be measured after skeletal muscle hyperemia is induced either by plantar flexion ergometry or after cuff occlusion, with the latter demonstrating greater reproducibility.50

Perfusion indices based on ASL have been shown to correlate with prognosis postrevascularization. In a study conducted by Chen et al., subjects with limited symptom improvement postrevascularization had a significantly lower preintervention microvascular index (physiological model derived from ASL perfusion-time curves).51 ASL has also been used to successfully quantify peri-wound perfusion in diabetics and could lend itself to developing a tool to assess perfusion deficits in ischemic wounds.52

Intravoxel incoherent motion MRI

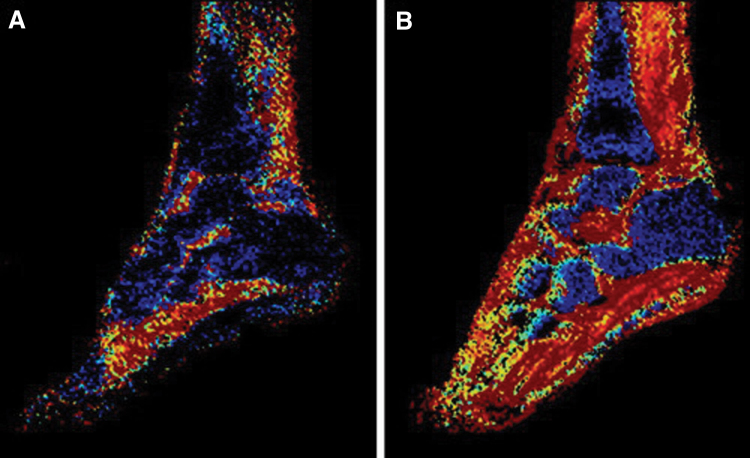

IVIM MRI is a method based on diffusion-weighted imaging, which estimates microvascular perfusion by assessing all the translational motion within a voxel, including both molecular diffusion of water and microperfusion in the capillary network. The signal decay in diffusion weighted images is fit to the advanced equation of an IVIM model and this is able to characterize microvascular perfusion53,54 (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Sagittal intravoxel incoherent motion microperfusion parametric map of flow-related pseudo-diffusion inside the capillary network in a patient with critical limb ischemia of the right lower extremity (A) and a normal patient (B). Reprinted from Galanakis et al.54 with permission from the British Institute of Radiology.

This technique has been used predominantly in oncologic and neurovascular imaging; however, more recently has been applied to perfusion of the LE. Perfusion estimated by IVIM-MRI has correlated well to that estimated by DCE-MRI in patients with PAD.55 It is also able to distinguish changes in microvascular blood flow in different LE muscle groups with increased activity.56 It has been shown to accurately detect changes in microvascular perfusion after revascularization. In a study by Galanakis et al., IVIM-MRI distinguished microvascular perfusion between patients with critical limb ischemia and healthy individuals and detected significant improvement in microvascular perfusion after revascularization.54

Blood oxygenation level dependent MRI

BOLD MRI is an imaging technique that was primarily developed for neuroradiology, but is gaining prominence for assessment of skeletal muscle perfusion/oxygenation. The technique is based on local changes in oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin and uses the paramagnetic effect of deoxygenated hemoglobin as an intrinsic contrast agent, which decreases the T2* relaxation signal.57

BOLD MRI has been found to have a good correlation with conventional methods of microvascular circulation and tissue oxygenation such as transcutaneous oxygen measurement (TCOM) and laser Doppler flowmetry, in detecting skeletal muscle ischemia and hyperemia in healthy subjects.57

In a study that used a quantitative MR technique called PIVOT—combined pulsed ASL, mixed venous oxygen saturation using MRI susceptometry, and BOLD MRI—to assess perfusion in patients with varying degrees of PAD versus controls, there were alterations in perfusion in PAD patients detected by this method compared to healthy controls.58 In a study by Suo et al., that compared assessment of skeletal muscle perfusion by ASL, IVIM, and BOLD, in PAD patients and healthy controls, perfusion metrics derived from all three methods correlated with tissue oxygenation determined by TCOM. BOLD was found to be a more reliable imaging technique for the detection of alterations in microvascular function at rest compared with ASL and IVIM.59

Phosphorus-31 magnetic resonance spectroscopy

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) allows the noninvasive detection and quantification of tissue metabolites. Phosphorus-31 MRS (31P MRS) has been used to study muscle metabolism by measuring high-energy phosphorylated compounds. It can be used to measure the recovery of phosphocreatine (PCr, which acts as a source of energy during exercise) after exercise, which serves as a surrogate measure of tissue ischemia. PCr recovery times are prolonged in patients with symptomatic PAD and this has been shown to be a reproducible method to identify patients with PAD from normal subjects. This technology remains limited to the realm of clinical research and is impaired by prolonged acquisition times and poor spatial resolution.60,61

Combinations of previously described techniques and 31P-MRS are being used in PAD research. In a study of patients with mild-moderate symptomatic PAD, where MRA was used to determine lesion severity, DCE-MRI to assess calf muscle perfusion, and 31P-MRS to assess energetics, it was shown that multiple factors, including plaque burden, macrovascular obstruction, reduced tissue perfusion, and abnormal skeletal muscle metabolism, all contributed to claudication. In this study, 31P-MRS measurement of PCr recovery time correlated to 6-min walk test but did not correlate to calf muscle perfusion, suggesting uncoupling between metabolism and perfusion.62 Combined methods have also been used to assess change in perfusion and metabolism after interventions. In a study of patients with symptomatic PAD who underwent revascularization measuring perfusion with DCE-MRI and PCr recovery time with 31P-MRS, there was an improvement in PCr kinetics and ABI without a change in perfusion.63

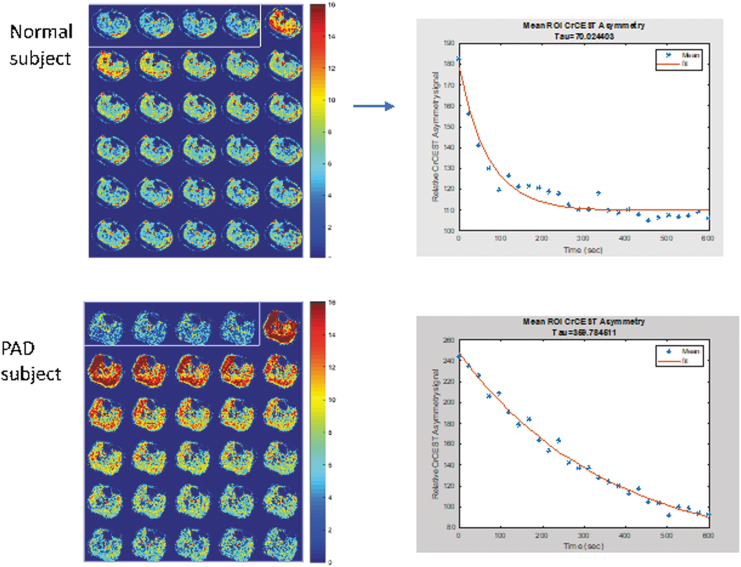

Chemical exchange saturation transfer

CEST is a novel contrast enhancement technique that allows the indirect detection of molecules that exchange protons with free water and is able to measure kinetics of creatine and other substrates in skeletal muscle while allowing for three orders-of-magnitude higher signal-to-noise ratio than 31P MRS61,62 (Fig. 9). In a recent study of PAD patients, it was found that CEST was able to distinguish PAD patients from controls with CEST decay times significantly longer in the former. Furthermore, CEST demonstrated good agreement with the PCr recovery time constant measured by 31P MRS. CEST has a higher spatial resolution than 31P MRS, creates an image, does not require multinuclear hardware, and is therefore likely more suitable for clinical studies in PAD than 31P MRS.64

Figure 9.

Chemical exchange saturation transfer of the calf in a normal and PAD patient acquired immediately after exercise with corresponding decay curves. Note the delay in reaching baseline deep blue and slower decay time in the patient with PAD compared to the normal subject.

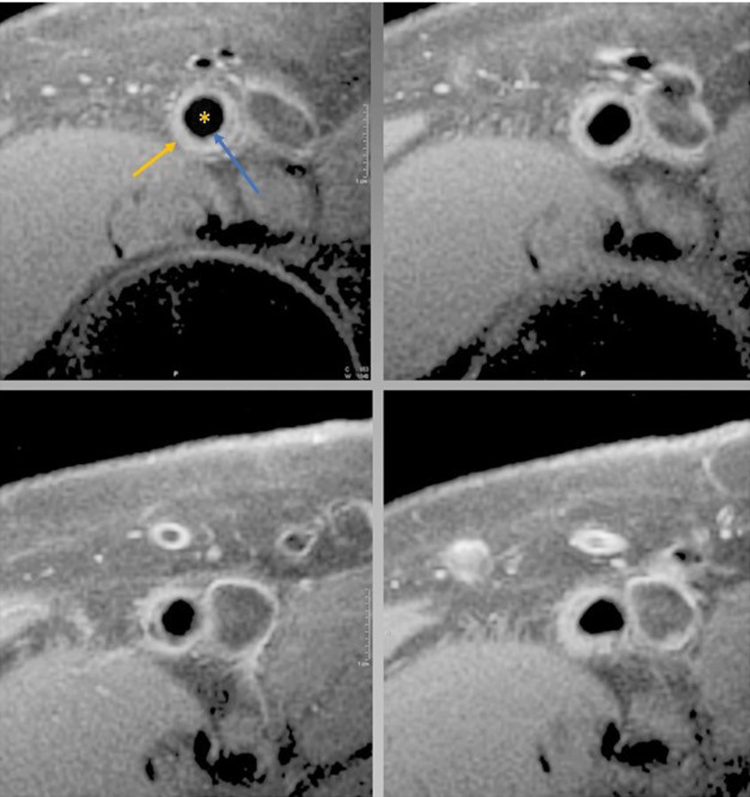

Plaque assessment by MRI

In addition to assessing macrovascular stenoses, microvascular perfusion, and energetics in the skeletal muscle of the lower extremities, MRI methods can be applied to characterize the volume and distribution of peripheral arterial plaque. Initial two dimensional black-blood turbo spin-echo (TSE) techniques have been supplanted by 3D techniques with improved signal-noise ratio, anatomic coverage, and spatial resolution.11,65

Various 3D black-blood imaging protocols that have all been shown to be feasible for evaluating plaque burden in PAD patients include 3D diffusion prepared steady state free precession (3D DP SSFP), SPACE (sampling perfection with application optimized contrasts using different flip angle resolution), DANTE (delay alternating with nutation for tailored excitation), and 3D MERGE (motion-sensitized driven equilibrium prepared rapid gradient echo sequence)65–68 (Fig. 10). Assessment of longitudinal distribution of LE vessel wall plaque using MRI with 3D-MERGE sequence in an asymptomatic elderly population showed that subclinical atherosclerosis was prevalent in this population and was significantly associated with cardiovascular risk factors.69 The DANTE sequence was studied with regard to its ability to detect plaque morphology and distribution in patients with PAD and diabetes. It performed well in this regard, and an association was also found between diabetic foot and increased wall thickness and wall area in the popliteal segments.70

Figure 10.

Representative sequential images from the superficial femoral artery (vessel with star) of a subject with mild to moderate peripheral artery disease with both the luminal (blue arrow) and adventitial border (yellow arrow) clearly delineated. Note the slice to slice variation in plaque morphology.

In an earlier study, the prevalence of superficial femoral artery atherosclerotic plaque in patients with diabetes and coronary disease, measured by MRI using T1 weighted fat-suppressed, spin-echo, was significantly higher than in age and gender matched controls. This was found in the setting of normal ABIs, indicating the utility of this modality for earlier detection and preventive intervention.71

Plaque eccentricity, composition, and morphology have also been studied using high spatial resolution multicontrast MRI. Plaque eccentricity was found to be associated with preserved lumen size and advanced plaque features such as larger plaque burden, increased lipid content, and calcification.72 The same group also studied the prevalence of high-risk plaque features, such as a lipid rich necrotic core (LRNC) and intraplaque hemorrhage among subjects with PAD and found an overall prevalence of high-risk features of <25%, although smoking was associated with LRNC.73

Plaque burden assessment by MRI has also served as an endpoint for randomized trials. Using a reproducible and reliable technique for plaque assessment, with a custom-built surface array placed over the most symptomatic limb, and a fat-suppressed multislice TSE sequence,74 plaque volume was measured in statin naive mild-moderate PAD patients before and after randomization to statin therapy alone or a statin with ezetimibe. Over 2 years of follow-up, the investigators found that statin initiation halted the progression of PAD as determined by plaque volume.75 Using the same technique, another trial found no change in plaque volume in patients randomized to canakinumab or placebo.76

SUMMARY

There has been a significant shift toward utilizing noninvasive imaging modalities for the diagnosis and surveillance of PAD. ABI, DUS, and CTA are commonly used, but associated with limitations. MRI-based techniques show significant promise, eliminating radiation exposure and use of iodinated contrast, and have had significant technical advances that have allowed increased accuracy and efficiency, although still limited to some degree by longer acquisition times and clinical availability. Contemporary research is predominantly focused on noncontrast approaches and on methods of assessing microvascular perfusion and skeletal muscle metabolism which can help better understand the pathophysiology of PAD and serve as methods of surveilling clinical outcomes of PAD interventions.

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

PAD leads to a significant burden of morbidity and impaired quality of life, with a high global prevalence.

Accurate noninvasive methods of diagnosis and surveillance are necessary in this population.

Conventional techniques such as ABI, DUS, CTA, remain workhorses in the field, yet are associated with limitations.

MRI based methods are attractive for several reasons, including the avoidance of radiation exposure and iodinated contrast.

Several noncontrast MRA methods have been developed which avoid all contrast material administration and have been demonstrated to be comparable to contrast enhanced MRA, CTA, and invasive angiography.

Contemporary research has focused on noncontrast MRI methods which are able to evaluate microvascular perfusion and skeletal muscle metabolism, both providing an additional layer of understanding into the pathophysiology of PAD, determining prognosis and show promise as methods of determining clinical outcomes for PAD interventions.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ABI

ankle-brachial index

- ASL

arterial spin labeling

- BOLD

blood-oxygen-level dependent

- bSSFP

balanced steady state free precession

- CE-MRA

contrast enhanced magnetic resonance angiography

- CEST

chemical exchange saturation transfer

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- CTA

computed tomographic angiography

- DCE-MRI

dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging

- DSA

digital subtraction angiography

- DUS

duplex ultrasonography

- FSD-MRA

flow sensitive dephasing magnetic resonance angiography

- FSE-MRA

fast spin echo magnetic resonance angiography

- GBCA

gadolinium based contrast agent

- IVIM

intravoxel incoherent motion

- LE

lower extremity

- LRNC

lipid rich necrotic core

- MRA

magnetic resonance angiography

- MRS

magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- NC-MRA

noncontrast magnetic resonance angiography

- NSF

nephrogenic systemic fibrosis

- PAD

peripheral arterial disease

- PC-MRA

phase contrast MRA

- PCr

phosphocreatine

- QISS

quiescent-interval single-shot

- RF

radiofrequency

- TCOM

transcutaneous oxygen measurement

- TOF-MRA

time of flight magnetic resonance angiography

- TSE

turbo spin echo

- VEG-F

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VS-MRA

velocity selective magnetic resonance angiography

AUTHOR CONFIRMATION

All authors listed in this article have contributed significantly to this article and agree to be a part of this review article.

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE AND GHOSTWRITING

Christopher M Kramer is supported by a research grant from NHLBI in this area. No ghostwriting services were used.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Nisha Hosadurg, MBBS is an advanced cardiovascular imaging fellow at the University of Virginia. Christopher M. Kramer, MD is a professor of Cardiology, Radiology and chief of the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine at the University of Virginia.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported, in part, by R01 HL075792 (CMK). NH is supported by T32 EB003841 and has no financial relationship or interest with any proprietary entity producing health care goods or services.

REFERENCES

- 1. Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association [published correction appears in Circulation 2022;146(10):e141]. Circulation 2022;145(8):e153–e639; doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Matsushita K, Sang Y, Ning H, et al. Lifetime risk of lower-extremity peripheral artery disease defined by ankle-brachial index in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8(18):e012177; doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fowkes FG, Rudan D, Rudan I, et al. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: A systematic review and analysis. Lancet 2013;382(9901):1329–1340; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61249-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paul DW, Ghassemi P, Ramella-Roman JC, et al. Noninvasive imaging technologies for cutaneous wound assessment: A review. Wound Repair Regen 2015;23(2):149–162; doi: 10.1111/wrr.12262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Greve JM, Williams SP, Bernstein LJ, et al. Reactive hyperemia and BOLD MRI demonstrate that VEGF inhibition, age, and atherosclerosis adversely affect functional recovery in a murine model of peripheral artery disease. J Magn Reson Imaging 2008;28(4):996–1004; doi: 10.1002/jmri.21517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Greve JM, Chico TJ, Goldman H, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography reveals therapeutic enlargement of collateral vessels induced by VEGF in a murine model of peripheral arterial disease. J Magn Reson Imaging 2006;24(5):1124–1132; doi: 10.1002/jmri.20731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tehan PE, Santos D, Chuter VH. A systematic review of the sensitivity and specificity of the toe-brachial index for detecting peripheral artery disease. Vasc Med 2016;21(4):382–389; doi: 10.1177/1358863X16645854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Vries SO, Hunink MG, Polak JF. Summary receiver operating characteristic curves as a technique for meta-analysis of the diagnostic performance of duplex ultrasonography in peripheral arterial disease. Acad Radiol 1996;3(4):361–369; doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(96)80257-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Met R, Bipat S, Legemate DA, et al. Diagnostic performance of computed tomography angiography in peripheral arterial disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2009;301(4):415–424; doi: 10.1001/jama.301.4.415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Takahashi EA, Kinsman KA, Neidert NB, et al. Guiding peripheral arterial disease management with magnetic resonance imaging. Vasa 2019;48(3):217–222; doi: 10.1024/0301-1526/a000742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mathew RC, Kramer CM. Recent advances in magnetic resonance imaging for peripheral artery disease. Vasc Med 2018;23(2):143–152; doi: 10.1177/1358863X18754694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Riederer SJ, Haider CR, Borisch EA, et al. Recent advances in 3D time-resolved contrast-enhanced MR angiography. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015;42(1):3–22; doi: 10.1002/jmri.24880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leiner T. Magnetic resonance angiography of abdominal and lower extremity vasculature. Top Magn Reson Imaging 2005;16(1):21–66; doi: 10.1097/01.rmr.0000185431.50535.d7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Koelemay MJ, Lijmer JG, Stoker J, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography for the evaluation of lower extremity arterial disease: A meta-analysis. JAMA 2001;285(10):1338–1345; doi: 10.1001/jama.285.10.1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Vries M, Ouwendijk R, Flobbe K, et al. Peripheral arterial disease: Clinical and cost comparisons between duplex US and contrast-enhanced MR angiography—a multicenter randomized trial. Radiology 2006;240(2):401–410; doi: 10.1148/radiol.2402050223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Healy DA, Boyle EM, Clarke Moloney M, et al. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography in diabetic patients with infra-genicular peripheral arterial disease: Systematic review. Int J Surg 2013;11(3):228–232; doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Healy DA, Boyle EM, Clarke Moloney M, et al. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography in diabetic patients with infra-genicular peripheral arterial disease: Systematic review. Int J Surg 2013;11(3):228–232; doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Woolen SA, Shankar PR, Gagnier JJ, et al. Risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in patients with stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease receiving a group II gadolinium-based contrast agent: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180(2):223–230; doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.5284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weinreb JC, Rodby RA, Yee J, et al. Use of Intravenous Gadolinium-based Contrast Media in Patients with Kidney Disease: Consensus Statements from the American College of Radiology and the National Kidney Foundation. Radiology 2021;298(1):28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Edelman RR, Koktzoglou I. Noncontrast MR angiography: An update. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019;49(2):355–373; doi: 10.1002/jmri.26288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cavallo AU, Koktzoglou I, Edelman RR, et al. Noncontrast magnetic resonance angiography for the diagnosis of peripheral vascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;12(5):e008844; doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.118.008844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Murata N, Gonzalez-Cuyar LF, Murata K, et al. Macrocyclic and other non-group 1 gadolinium contrast agents deposit low levels of gadolinium in brain and bone tissue: Preliminary results from 9 patients with normal renal function. Invest Radiol 2016;51(7):447–453; doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kanda T, Ishii K, Kawaguchi H, et al. High signal intensity in the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus on unenhanced T1-weighted MR images: Relationship with increasing cumulative dose of a gadolinium-based contrast material. Radiology 2014;270(3):834–841; doi: 10.1148/radiol.13131669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Laub GA. Time-of-flight method of MR angiography. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 1995;3(3):391–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hutter J, Grimm R, Forman C, et al. Highly undersampled peripheral Time-of-Flight magnetic resonance angiography: Optimized data acquisition and iterative image reconstruction. MAGMA 2015;28(5):437–446; doi: 10.1007/s10334-014-0477-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang N, Zou L, Huang Y, et al. Non-Contrast Enhanced MR Angiography (NCE-MRA) of the Calf: A Direct Comparison between Flow-Sensitive Dephasing (FSD) Prepared Steady-State Free Precession (SSFP) and Quiescent-Interval Single-Shot (QISS) in Patients with Diabetes. PLoS One 2015;10(6):e0128786; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reimer P, Boos M. Phase-contrast MR angiography of peripheral arteries: Technique and clinical application. Eur Radiol 1999;9(1):122–127; doi: 10.1007/s003300050642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Edelman RR, Giri S, Murphy IG, et al. Ungated radial quiescent-inflow single-shot (UnQISS) magnetic resonance angiography using optimized azimuthal equidistant projections. Magn Reson Med 2014;72(6):1522–1529; doi: 10.1002/mrm.25477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hodnett PA, Ward EV, Davarpanah AH, et al. Peripheral arterial disease in a symptomatic diabetic population: Prospective comparison of rapid unenhanced MR angiography (MRA) with contrast-enhanced MRA. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011;197(6):1466–1473; doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.6091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Varga-Szemes A, Aouad P, Schoepf UJ, et al. Comparison of 2D and 3D quiescent-interval slice-selective non-contrast MR angiography in patients with peripheral artery disease. MAGMA 2021;34(5):649–658; doi: 10.1007/s10334-021-00927-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wei LM, Zhu YQ, Zhang PL, et al. Evaluation of Quiescent-Interval Single-Shot Magnetic Resonance Angiography in Diabetic Patients With Critical Limb Ischemia Undergoing Digital Subtraction Angiography: Comparison With Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Angiography With Calf Compression at 3.0 Tesla. J Endovasc Ther 2019;26(1):44–53; doi: 10.1177/1526602818817887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lam A, Perchyonok Y, Ranatunga D, et al. Accuracy of non-contrast quiescent-interval single-shot and quiescent-interval single-shot arterial spin-labelled magnetic resonance angiography in assessment of peripheral arterial disease in a diabetic population. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2020;64(1):35–43; doi: 10.1111/1754-9485.12987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Decker JA, Fischer AM, Schoepf UJ, et al. Quiescent-interval slice-selective MRA accurately estimates intravascular stent dimensions prior to intervention in patients with peripheral artery disease. J Magn Reson Imaging 2022;55(1):246–254; doi: 10.1002/jmri.27864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Edelman RR, Carr M, Koktzoglou I. Advances in non-contrast quiescent-interval slice-selective (QISS) magnetic resonance angiography. Clin Radiol 2019;74(1):29–36; doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2017.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Miyazaki M, Takai H, Sugiura S, et al. Peripheral MR angiography: Separation of arteries from veins with flow-spoiled gradient pulses in electrocardiography-triggered three-dimensional half-Fourier fast spin-echo imaging. Radiology 2003;227(3):890–896; doi: 10.1148/radiol.2273020227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schubert T, Takes M, Aschwanden M, et al. Non-enhanced, ECG-gated MR angiography of the pedal vasculature: Comparison with contrast-enhanced MR angiography and digital subtraction angiography in peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Eur Radiol 2016;26(8):2705–2713; doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-4068-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lim RP, Hecht EM, Xu J, et al. 3D nongadolinium-enhanced ECG-gated MRA of the distal lower extremities: Preliminary clinical experience. J Magn Reson Imaging 2008;28(1):181–189; doi: 10.1002/jmri.21416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nakamura K, Miyazaki M, Kuroki K, et al. Noncontrast-enhanced peripheral MRA: Technical optimization of flow-spoiled fresh blood imaging for screening peripheral arterial diseases. Magn Reson Med 2011;65(2):595–602; doi: 10.1002/mrm.22614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Demirtaş H, Parpar T, Değirmenci B, et al. Unenhanced 3D turbo spin echo MR angiography of lower extremity arteries: Comparison with 128-MDCT angiography. Radiol Med 2016;121(12):916–925; doi: 10.1007/s11547-016-0678-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hanrahan CJ, Lindley MD, Mueller M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of noncontrast MR angiography protocols at 3T for the detection and characterization of lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2018;29(11):1585–1594.e2; doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2018.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Altaha MA, Jaskolka JD, Tan K, et al. Non-contrast-enhanced MR angiography in critical limb ischemia: Performance of quiescent-interval single-shot (QISS) and TSE-based subtraction techniques. Eur Radiol 2017;27(3):1218–1226; doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4448-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu X, Fan Z, Zhang N, et al. Unenhanced MR angiography of the foot: Initial experience of using flow-sensitive dephasing-prepared steady-state free precession in patients with diabetes. Radiology 2014;272(3):885–894; doi: 10.1148/radiol.14132284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wedeen VJ, Meuli RA, Edelman RR, et al. Projective imaging of pulsatile flow with magnetic resonance. Science 1985;230(4728):946–948; doi: 10.1126/science.4059917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shin T, Menon RG, Thomas RB, et al. Unenhanced Velocity-Selective MR Angiography (VS-MRA): Initial clinical evaluation in patients with peripheral artery disease. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019;49(3):744–751; doi: 10.1002/jmri.26268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Isbell DC, Epstein FH, Zhong X, et al. Calf muscle perfusion at peak exercise in peripheral arterial disease: Measurement by first-pass contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 2007;25(5):1013–1020; doi: 10.1002/jmri.20899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang JL, Layec G, Hanrahan C, et al. Exercise-induced calf muscle hyperemia: Quantitative mapping with low-dose dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2019;316(1):H201–H211; doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00537.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pohmann R, Künnecke B, Fingerle J, et al. Fast perfusion measurements in rat skeletal muscle at rest and during exercise with single-voxel FAIR (flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery). Magn Reson Med 2006;55(1):108–115; doi: 10.1002/mrm.20737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wu WC, Mohler E 3rd, Ratcliffe SJ, et al. Skeletal muscle microvascular flow in progressive peripheral artery disease: Assessment with continuous arterial spin-labeling perfusion magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53(25):2372–2377; doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pollak AW, Meyer CH, Epstein FH, et al. Arterial spin labeling MR imaging reproducibly measures peak-exercise calf muscle perfusion: A study in patients with peripheral arterial disease and healthy volunteers. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;5(12):1224–1230; doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lopez D, Pollak AW, Meyer CH, et al. Arterial spin labeling perfusion cardiovascular magnetic resonance of the calf in peripheral arterial disease: Cuff occlusion hyperemia vs exercise. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2015;17(1):23; doi: 10.1186/s12968-015-0128-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chen HJ, Roy TL, Wright GA. Perfusion measures for symptom severity and differential outcome of revascularization in limb ischemia: Preliminary results with arterial spin labeling reactive hyperemia. J Magn Reson Imaging 2018;47(6):1578–1588; doi: 10.1002/jmri.25910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pantoja JL, Ali F, Baril DT, et al. Arterial spin labeling magnetic resonance imaging quantifies tissue perfusion around foot ulcers. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech 2022;8(4):817–524; doi: 10.1016/j.jvscit.2022.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Paschoal AM, Leoni RF, Dos Santos AC, et al. Intravoxel incoherent motion MRI in neurological and cerebrovascular diseases. Neuroimage Clin 2018;20:705–714; doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Galanakis N, Maris TG, Kalaitzakis G, et al. Evaluation of foot hypoperfusion and estimation of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty outcome in patients with critical limb ischemia using intravoxel incoherent motion microperfusion MRI. Br J Radiol 2021;94(1125):20210215; doi: 10.1259/bjr.20210215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ioannidis GS, Marias K, Galanakis N, et al. A correlative study between diffusion and perfusion MR imaging parameters on peripheral arterial disease data. Magn Reson Imaging 2019;55:26–35; doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2018.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jungmann PM, Pfirrmann C, Federau C. Characterization of lower limb muscle activation patterns during walking and running with Intravoxel Incoherent Motion (IVIM) MR perfusion imaging. Magn Reson Imaging 2019;63:12–20; doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2019.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ledermann HP, Heidecker HG, Schulte AC, et al. Calf muscles imaged at BOLD MR: Correlation with TcPO2 and flowmetry measurements during ischemia and reactive hyperemia—initial experience. Radiology 2006;241(2):477–484; doi: 10.1148/radiol.2412050701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Englund EK, Langham MC, Li C, et al. Combined measurement of perfusion, venous oxygen saturation, and skeletal muscle T2* during reactive hyperemia in the leg. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2013;15(1):70; doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-15-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Suo S, Zhang L, Tang H, et al. Evaluation of skeletal muscle microvascular perfusion of lower extremities by cardiovascular magnetic resonance arterial spin labeling, blood oxygenation level-dependent, and intravoxel incoherent motion techniques. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2018;20(1):18; doi: 10.1186/s12968-018-0441-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Isbell DC, Berr SS, Toledano AY, et al. Delayed calf muscle phosphocreatine recovery after exercise identifies peripheral arterial disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47(11):2289–2295; doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.12.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kogan F, Haris M, Debrosse C, et al. In vivo chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging of creatine (CrCEST) in skeletal muscle at 3T. J Magn Reson Imaging 2014;40(3):596–602; doi: 10.1002/jmri.24412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Anderson JD, Epstein FH, Meyer CH, et al. Multifactorial determinants of functional capacity in peripheral arterial disease: Uncoupling of calf muscle perfusion and metabolism. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54(7):628–635; doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. West AM, Anderson JD, Epstein FH, et al. Percutaneous intervention in peripheral artery disease improves calf muscle phosphocreatine recovery kinetics: A pilot study. Vasc Med 2012;17(1):3–9; doi: 10.1177/1358863X11431837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sporkin HL, Patel TR, Betz Y, et al. Chemical exchange saturation transfer magnetic resonance imaging identifies abnormal calf muscle-specific energetics in peripheral artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2022;15(7):e013869; doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.121.013869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hayashi K, Mani V, Nemade A, et al. Comparison of 3D-diffusion-prepared segmented steady-state free precession and 2D fast spin echo imaging of femoral artery atherosclerosis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2010;26(3):309–321; doi: 10.1007/s10554-009-9544-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zhang Z, Fan Z, Carroll TJ, et al. Three-dimensional T2-weighted MRI of the human femoral arterial vessel wall at 3.0 Tesla. Invest Radiol 2009;44(9):619–626; doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181b4c218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Xie G, Zhang N, Xie Y, et al. DANTE-prepared three-dimensional FLASH: A fast isotropic-resolution MR approach to morphological evaluation of the peripheral arterial wall at 3 Tesla. J Magn Reson Imaging 2016;43(2):343–351; doi: 10.1002/jmri.24986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chiu B, Sun J, Zhao X, et al. Fast plaque burden assessment of the femoral artery using 3D black-blood MRI and automated segmentation. Med Phys 2011;38(10):5370–5384. doi: 10.1118/1.3633899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Han Y, Guan M, Zhu Z, et al. Assessment of longitudinal distribution of subclinical atherosclerosis in femoral arteries by three-dimensional cardiovascular magnetic resonance vessel wall imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2018;20(1):60; doi: 10.1186/s12968-018-0482-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wang L, Deng W, Liang J, et al. Detection and prediction of peripheral arterial plaque using vessel wall MR in patients with diabetes. BioMed Res Int 2021:2021;5585846; doi: 10.1155/2021/5585846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bourque JM, Schietinger BJ, Kennedy JL, et al. Usefulness of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging of the superficial femoral artery for screening patients with diabetes mellitus for atherosclerosis. Am J Cardiol 2012;110(1):50–56; doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.02.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Li F, McDermott MM, Li D, et al. The association of lesion eccentricity with plaque morphology and components in the superficial femoral artery: A high-spatial-resolution, multi-contrast weighted CMR study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2010;12(1):37; doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-12-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Polonsky TS, Liu K, Tian L, et al. High-risk plaque in the superficial femoral artery of people with peripheral artery disease: Prevalence and associated clinical characteristics. Atherosclerosis 2014;237(1):169–176; doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.08.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Isbell DC, Meyer CH, Rogers WJ, et al. Reproducibility and reliability of atherosclerotic plaque volume measurements in peripheral arterial disease with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2007;9(1):71–76; doi: 10.1080/10976640600843330. Erratum in: J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2007;9: 629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. West AM, Anderson JD, Meyer CH, et al. The effect of ezetimibe on peripheral arterial atherosclerosis depends upon statin use at baseline. Atherosclerosis 2011;218(1):156–162; doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Russell KS, Yates DP, Kramer CM, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of canakinumab in patients with peripheral artery disease. Vasc Med 2019;24(5):414–421; doi: 10.1177/1358863X19859072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]