Abstract

The presence of staphylococcal superantigenic toxins in the supernatants of liquid cultures was detected by an easy and rapid method assessing the activation of T lymphocytes by cytofluorimetric measurement of CD69 expression. Staphylococcus aureus cells were grown in Eagle’s minimum essential medium supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum. Supernatant fluids from all S. aureus strains producing superantigen-related toxins, including enterotoxins A to E, toxic shock syndrome toxin, and exfoliative toxins A and B, induced CD69 expression in a significantly higher number of T cells than a cutoff of 2%. This CD69 assay might be used for initial detection of superantigens from S. aureus strains isolated in the context of staphylococcal toxemia or related chronic human diseases such as atopic dermatitis or Kawasaki syndrome.

Staphylococcus aureus produces a wide variety of toxic proteins including the staphylococcal enterotoxins A through E (SEA through SEE), the toxic shock syndrome toxin (TSST-1), and the exfoliative toxins A and B (ETA and -B). These toxins are responsible for various acute staphylococcal toxemias, such as toxic shock syndrome (mainly due to TSST-1, SEB, and SEC), scalded-skin syndrome (due to the exfoliative toxins), and staphylococcal food poisoning (due to the SEs) (2). These staphylococcal proteins are also suspected of playing a critical role in the pathogenesis of allergic and autoimmune human diseases, such as atopic dermatitis associated with SEA production or arthritis and Kawasaki syndrome associated with TSST-1 production (18). All of these toxins exhibit superantigenic activity, stimulating polyclonal T-cell proliferation through coligation between major histocompatibility complex class II molecules on antigen-presenting cells and the variable portion of the T-cell antigen receptor β chain (TCR Vβ) (14). Activated T cells express a number of surface receptors, of which CD69 is the earliest detected after stimulation by a variety of mitogenic agents (19). CD69 expression can be assessed by multiparameter flow cytometry, and the profile is synonymous with the activation of T cells (13). This method employs a two-color immunofluorescence staining protocol detecting CD69 on the T cell identified by CD3 expression of the population. This method has been used to detect T-cell activation in response to purified SEB (5, 13) but has not been well evaluated for other staphylococcal superantigens, particularly in unpurified culture supernatants.

In routine practice, staphylococcal superantigens are detected by immunological assays or the presence of the corresponding genes (7, 8, 20). These methods require separate tests for each toxin and recognize only previously characterized superantigens (TSST-1, SEA through E, and ETA and -B). We have tested a CD69 cytofluorimetric assay measuring T-cell activation as a suitable general screening method for the presence of S. aureus superantigenic toxins. The CD69 assay was evaluated on crude culture supernatants from known superantigenic toxin-producing strains, clinical isolates, and various controls and proved to be an effective alternative for toxin detection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and toxin detection.

Strains examined were from the French National Référence Center for Staphylococci (Lyon, France). These included reference strains known to produce only one toxin (SEA through SEE, TSST-1, and ETA and ETB); a non-toxin producer reference strain (see Tables 1 and 2); 28 clinical S. aureus strains isolated in the context of toxic shock or scalded-skin syndrome and known to produce either SEs, TSST-1, or ETA or -B (four epidemiologically nonrelated strains were selected for each toxin); and 14 other unrelated clinical S. aureus strains producing none of these toxins, all isolated from nontoxemic human infections (bacteremia, meningitis, and wound infections). SEA through -E were assessed from postexponential culture supernatants in brain heart infusion broth or in Eagle’s minimum essential medium, with Earle’s Salts supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (EMEM plus FCS) (Biowhittaker, Gagny, France) by the enzyme linked immunoassay RIDASCREEN SET A, B, C, D, E (R-Bio Pharm GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany). Specific genes (tst, eta, and etb) were detected by PCR amplification. Briefly, genomic DNA was extracted from staphylococcal cultures (3) and used as a template for amplification with primers and thermal profiles previously shown to be specific for tst, eta, and etb (8). The PCR products were then analyzed by electrophoresis through 1.5% agarose gels (Sigma, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France), followed by ethidium bromide staining.

TABLE 1.

CD69 expression on CD3+ lymphocytes induced by supernatants from reference strains of S. aureus

| Strain (origin or reference) | Toxina | CD69 expression (%)b |

|---|---|---|

| FRIS6 (M. S. Bergdoll) (12) | SEB | 15.1 ± 1.1c |

| RN450 (R. P. Novick) (16) | None | 0.7 ± 0.3 |

| Control | ||

| EMEM + FCS | 0.3 ± 0.2 | |

| EMEM + FCS + PHAd (20 μg/ml) | 75.4 ± 4.0 |

The toxin production in EMEM plus FCS was confirmed by enzyme immunoassays.

Percentage of CD69-positive cells was determined after electronic gating of the CD3+ population. All 10 experiments used separate samples of blood from one donor (donor no. 1). Results shown are means ± standard deviations.

Statistically significant differences (P < 0.001) in CD69 expression between FRIS6 (SEB producer) and RN450 (nonproducer) were determined by the Student t test.

PHA, Phaseolus vulgaris agglutinin.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of CD69 expression on CD3+ lymphocytes from three different blood donors, induced by supernatants from reference strains of S. aureus

| Strain (origin or reference) | Toxin produc- tiona | CD69 expression (%) with blood fromb:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor 1 | Donor 2 | Donor 3 | ||

| FRIS6 (M. S. Bergdoll) (12) | SEB | 13.8 ± 2.4c | 9.7 | 8.1 |

| A870502 (this study) | SEA | 8.9 ± 1.9c | 5.7 | 7.8 |

| FRI137 (M. S. Bergdoll) (17) | SEC | 5.4 ± 1.5c | 4.3 | 4.4 |

| FRI1151m (M. S. Bergdoll) (9) | SED | 5.2 ± 0.3c | 5.0 | 8.5 |

| FRI326 (M. S. Bergdoll; ATCC27664) | SEE | 10.2 ± 1.4c | 6.5 | 10.9 |

| FRI1169 (M. S. Bergdoll) (4) | TSST-1 | 7.8 ± 0.2c | 3.9 | 5.7 |

| TC7 (J. P. Arbuthnott) (1) | ETA | 11.2 ± 0.6c | 8.8 | 10.8 |

| TC146 (J. P. Arbuthnott) (1) | ETB | 4.2 ± 0.8c | 3.9 | 5.7 |

| RN450 (R. P. Novick) (16) | None | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Control | ||||

| EMEM + FCS | None | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

For SEA to SEE, the toxin production in EMEM plus FCS was confirmed by enzyme immunoassays.

Percentage of CD69-positive cells was determined after electronic gating of the CD3+ population. Blood samples from donor no. 2 and 3 were each used once, while blood from donor no. 1 was used three times, and the results shown are means ± standard deviations.

Statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) in CD69 expression between superantigen producer and RN450 (nonproducer) were determined by the nonparametric Wilcoxon test.

CD69 assay.

Staphylococcal supernatants for the CD69 assay were prepared from overnight cultures in EMEM plus FCS at 37°C with shaking. After centrifugation, the supernatants were sterilized by filtration through 0.22-μm-pore-size filters (Millipore, Molstein, France) and stored at −20°C until used.

Whole blood of healthy donors was collected in tubes containing sodium heparin as an anticoagulant. Specific activation of T cells by superantigens present in culture supernatants was determined essentially as described by Maino et al. (13). Briefly, 50 μl of whole blood was incubated with either (i) 50 μl of EMEM plus FCS, (ii) 50 μl of undiluted culture supernatant, (iii) 50 μl of undiluted culture supernatant derived from RN450 (known not to produce toxin) supplemented with purified SEB at the indicated concentrations, or (iv) 50 μl of 20 μg of Phaseolus vulgaris agglutinin (Sigma, l’Ile d’Abeau Chenes, France) per ml as a positive control for 24 h at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. After ammonium chloride lysis of erythrocytes, leukocytes were stained with a commercial antibody combination consisting of anti-CD3 (Leu3a) conjugated with cyanin-5-phycoerythrin, anti-CD4 (Leu4) conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate, and anti-CD69 (Leu23) conjugated with phycoerythrin (Becton-Dickinson, Le Pont de Claix, France). Cells were analyzed with a Facscan flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson). Statistically significant differences (P < 0.001) in CD69 expression among the two groups of strains (superantigen producer versus nonproducer) were assessed by the nonparametric Wilcoxon test or the Student t test.

RESULTS

Since brain heart medium induces nonspecific activation of human T lymphocytes (data not shown), it was decided to evaluate the capacity of S. aureus strains to grow in defined cell culture media. EMEM plus 5% FCS satisfactorily supported growth of all S. aureus strains tested and production of SEA to SEE by the relevant references strains (Tables 1 and 2). EMEM plus 5% FCS was therefore used for subsequent determinations.

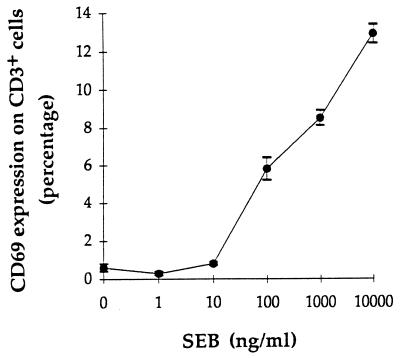

The conditions for monitoring staphylococcal superantigen production were evaluated by comparing the SEB-producing strain S. aureus FRIS6 with the negative control S. aureus RN450. Supernatants from S. aureus FRIS6 cultures were always found to induce substantial expression of CD69 on CD3+ lymphocytes (15.1% ± 1.1%), whereas supernatants from S. aureus RN450 cultures induced CD69 expression in less than 1.2% of cells (0.7% ± 0.3%), and the reagent negative control (EMEM plus 5% FCS) induced CD69 expression in fewer than 0.6% of cells (Table 1). A cutoff value for positivity was therefore established at a level of 2%, which corresponded to the mean plus 4 standard deviations of the values obtained with strain RN450 (producing no superantigen). Supplementation of RN450 with greater than 10 ng of purified SEB per ml restored the dose-response kinetics of the CD69 expression (Fig. 1). Hence, at the 2% cutoff value, the sensitivity of the assay could be estimated as 20 ng/ml.

FIG. 1.

CD69 expression on CD3+ lymphocytes induced by defined concentrations of SEB. Relative expression of CD69 on CD3+ cells obtained from blood donor no. 1 is shown after induction by supernatants of RN450 (nonproducer) supplemented with purified SEB at the indicated concentrations. Values are means ± standard deviations of triplicate experiments.

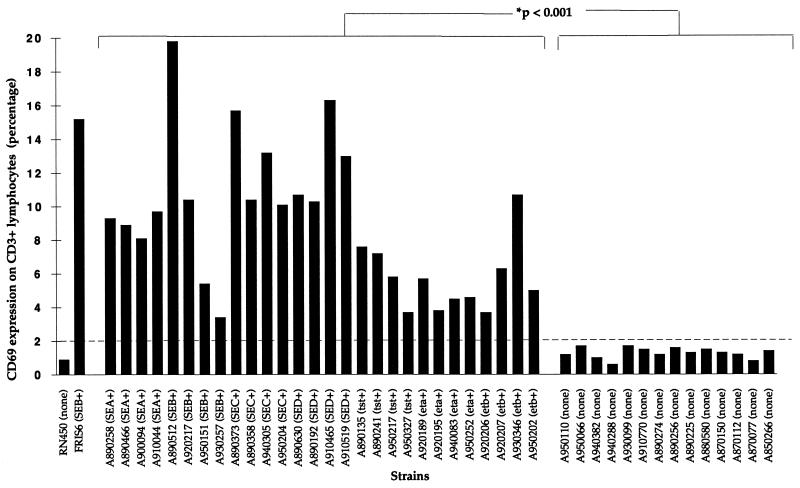

As shown in Table 2, similar increases were observed in the CD69 expression of normal human lymphocytes obtained from three healthy donors after incubation with supernatants from staphylococcal strains producing superantigenic toxins (SEA, SEB, SEC, SED, SEE, TSST-1, ETA, and ETB). All toxin-producing strains, but no control strains, induced CD69 expression in >2% of CD3+ lymphocytes. As revealed in Fig. 2, supernatants from 28 clinical isolates of staphylococci, isolated from patients with toxic shock or scalded-skin syndromes, all induced CD69 expression in more than 2% of lymphocytes, while 14 toxin-negative clinical isolates induced expression in fewer than 1.7% of CD3+ cells (P < 0.001; the Student t test). Thus, the probability that nonproducer strains induce a value greater than 2% for CD69 is 0.004 when evaluation is done by the t test with all results obtained with nonproducer strains (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Relative expression of CD69 on CD3+ lymphocytes induced by clinical S. aureus strains. Relative expression of CD69 on CD3+ cells obtained from blood donor no. 1 is shown after induction by supernatants of S. aureus superantigen producers compared to nonproducers as assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (SEA to -D) or PCR (tst, eta, and etb). Statistically significant differences (P < 0.001) in CD69 expression between the two groups of strains (superantigen producer versus nonproducer) were assessed by the Student t test.

DISCUSSION

The rapid demonstration of a capacity for superantigen production in clinical isolates of staphylococci can influence decisions about patient care and treatment. At present, assays require separate testing for individual toxins or use of radioactive reagents to detect mitogenic activity (11). This paper presents an alternative approach which detects the functional activity of superantigens in crude staphylococcal supernatants on normal human lymphocytes without the use of radioactivity.

A satisfactory test should detect all superantigen activities and yet distinguish these from direct or interleukin-1-mediated T-cell activation due to products of all staphylococci, such as heat shock proteins, hemolysins, peptidoglycans, teichoic acid, and capsular polysaccharides (6, 10, 21). Follow-up testing by conventional methods such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or PCR would then identify the precise superantigen involved (7, 8, 20).

The described assay uses readily available nonradioactive reagents and evaluates the percentage of CD3+ leukocytes from a healthy donor which are induced to express the CD69 marker after incubation with supernatant from a short-term culture of a staphylococcal isolate. Only superantigen-producing strains induce CD69 expression in more than 2% of CD3+ leukocytes from three different healthy donors, hence indicating that other mechanisms of T-cell activation do not interfere in this system. The minor differences observed in the intensity of CD69 expression among the three healthy donors are probably due to differences in their TCR Vβ subsets or to incidental immunization against staphylococcal superantigens.

The cutoff at the 2% level of expressing cells determined in this study corresponds to a sensitivity of 20 ng of superantigenic toxin (SEB) per ml for the technique used and permits a clear separation between 28 toxin-positive and 14 toxin-negative clinical isolates (P < 0.001; Student’s t test) (Fig. 2).

The proposed assay is based on the functional capacity of the toxins to activate a significant proportion of normal T cells and is thus relevant to the mechanism of toxic action (15). It requires bacterial culture conditions which permit an adequate expression of superantigens (20) but which do not themselves induce activation of normal T cells. We have found that EMEM with 5% FCS satisfies both of these conditions, whereas brain heart broth causes nonspecific T-cell activation. The test is simple, precise, and quite rapid. It can detect superantigen activity due to known or novel molecules, and it should contribute to studies of the host-related factors and cytokines involved in the individual patient’s response to staphylococcal infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to J. P. Revillard for scientific advice; to M. Goldner for editing the manuscript; and to D. Thouvenot, M. Thome, and N. Violland for their technical cooperation and assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arbuthnott J P, Billcliffe B. Qualitative and quantitative methods for detecting staphylococcal epidermolytic toxin. J Med Microbiol. 1976;9:191–201. doi: 10.1099/00222615-9-2-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arbuthnott J P, Coleman D C, de Azavedo J S. Staphylococcal toxins in human disease. Soc Appl Bacteriol Symp Ser. 1990;19:101S–107S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb01802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore B D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley Interscience; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu M C, Kreiswirth B N, Pattee P A, Novick R P, Melish M E, James J J. Association of toxic shock toxin-1 determinant with a heterologous insertion at multiple loci in the Staphylococcus aureus chromosome. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2702–2708. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.10.2702-2708.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dannecker G, Mahlknecht U, Schultz H, Hoffman M K. Activation of human T cells by the superantigen Staphylococcus enterotoxin B: analysis on a cellular level. Immunology. 1994;190:116–126. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80287-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haregewoin A, Soman G, Hom R C, Finberg R W. Human γδ+ T cells respond to mycobacterial heat-shock protein. Nature. 1989;340:309–312. doi: 10.1038/340309a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaulhac B, Bes M, Bornstein N, Piemont Y, Brun Y, Fleurette J. Synthetic DNA probes for detection of genes for enterotoxins A, B, C, D, E and TSST-1 in staphylococcal strains. J Appl Microbiol. 1992;72:386–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb01851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson W M, Tyler S D, Ewan E P, Asthon F E, Pollard D R, Rozee K R. Detection of genes for enterotoxins, exfoliative toxins, and toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 in Staphylococcus aureus by the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:426–430. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.3.426-430.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kokan N P, Bergdoll M S. Detection of low-enterotoxin-producing Staphylococcus aureus strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:2675–2676. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.11.2675-2676.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.König B, Köller M, Prevost G, Piemont Y, Alouf J E, Schreiner A, König W. Activation of human effector cells by different bacterial toxins (leukocidin, alveolysin, and erythrogenic toxin A): generation of interleukin-8. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4831–4837. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4831-4837.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lina G, Fleer A, Etienne J, Greenland T B, Vandenesch F. Coagulase negative staphylococci isolated from two cases of toxic shock syndrome lack superantigenic activity, but induce cytokine production. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1996;13:81–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1996.tb00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahmood R, Khan S A. Role of upstream sequences in the expression of the staphylococcal enterotoxin B gene. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:4652–4656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maino V C, Suni M A, Ruitenberg J J. Rapid flow cytometric method for measuring lymphocyte subset activation. Cytometry. 1995;20:127–133. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990200205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marrack P, Kappler J. The staphylococcal enterotoxins and their relatives. Science. 1990;248:705–711. doi: 10.1126/science.2185544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miethke T, Gaus H, Wahl C, Heeg K, Wagner H. T-cell-dependent shock induced by a bacterial superantigen. Chem Immunol. 1992;55:172–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novick R P, Brodsky R. Studies on plasmid replication. I. Plasmid incompatibility and establishment in Staphylococcus aureus. J Mol Biol. 1972;68:285–302. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90214-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regassa L B, Couch J L, Betley M J. Steady-state staphylococcal enterotoxin type C mRNA is affected by a product of the accessory gene regulator (agr) and by glucose. Infect Immun. 1991;59:955–962. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.3.955-962.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schlievert P M. Role of superantigens in human disease. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:997–1002. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Testi R, Phillips J H, Lanier L L. Leu 23 induction as an early marker of functional CD3/T cell antigen receptor triggering: Requirement for receptor cross-linking, prolonged elevation of intracellular [Ca+] and stimulation of protein kinase. J Immunol. 1989;142:1854–1860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tranter H S, Brehm R D. Production, purification and identification of the staphylococcal enterotoxins. Soc Appl Bacteriol Symp Ser. 1990;19:109S–122S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb01803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verhoef J, Mattsson E. The role of cytokines in Gram-positive bacterial shock. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:136–140. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88902-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]