Abstract

The PCR technique was applied to the diagnosis of tuberculosis in live cattle, and both skin-test-negative and skin-test-positive animals were studied. DNA was taken from various sources including specimens of lymph node aspirates, milk, and nasal swabs. After slaughter and visual inspection, tissues such as lymph nodes, lungs, and udders from tuberculin reactors were tested by the same technique. Specific oligonucleotide primers internal to the IS6110 insertion element were used to amplify a 580-bp fragment. A 182-bp fragment was obtained by designating a nested PCR from the first amplification product. This fragment was cloned and sequenced, and after being labeled it was employed in dot blot hybridization. A total of 100 cattle were tested, and PCR analysis was performed using nasal swab, milk, and lymph node aspirate. Sixty skin-test-positive cows were also tested to detect mycobacterial DNA in tissue samples from lymph nodes, lungs, and udders, and the infection was confirmed in all of the animals. Using PCR analysis of tissue samples from slaughtered animals as a “gold standard” we calculated 100% values for sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for milk and lymph node aspirate samples. The respective values for nasal swab samples were 58, 100, 100, and 28%. The respective values for all of the samples were 74, 100, 100, and 35%, while for visual inspection the values were 81, 100, 100, and 58%, respectively. PCR analysis of specimens of lymph node aspirates, milk, and nasal swabs from skin-test-negative animals showed that 52% of these skin test results were false negatives. These animals, not being removed from the farms, represent a potential source of further infection.

Mycobacterium bovis, the cause of tuberculosis in cattle, is also a pathogen for a large number of other animals, and its transmission to humans constitutes a public health problem (10). The diagnosis of bovine tuberculosis in live animals mainly depends on clinical manifestations of the disease, skin testing, and subsequent identification of the pathogen by biochemical testing. It is known that the skin test lacks sufficient sensitivity and specificity in many cases (8, 9, 16, 21). Neill and coworkers (15) have reported that M. bovis may be isolated from the secretions of skin-test-negative cattle and, furthermore, that these animals were not anergic, as is sometimes the case in the later stages of the disease.

Identification of the mycobacterium is based on the traditional method with the Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast stain and on the pigmentation, growth rate, and gross and microscopic colony morphologies of cultures of the isolated causative organism. Biochemical methods such as tests for niacin, catalase, nitrate reduction, and urease are used to identify different species.

The Ziehl-Neelsen stain is very rapid but lacks specificity and cannot be used to distinguish between the various members of the family Mycobacteriaceae, while the other procedures usually require 4 to 8 weeks to obtain good growth. In order to be certain of the diagnosis of tuberculosis postmortem histopathological examination of organ lesions is carried out.

In the past few years molecular approaches to diagnosis have been transforming the investigation of tuberculosis, especially in human medicine. The introduction of PCR and nucleic acid hybridization has greatly reduced identification time (3), and the use of PCR has improved the level of detection in clinical specimens. It has been previously reported (14) that by amplifying species-specific DNA sequences, and hybridizing the amplified sequence with a labeled probe, 5 fg of mycobacterial DNA (corresponding to one mycobacterium) can be detected in clinical samples. Rapid diagnosis by PCR with a number of different targets (11, 17), including the IS6110 insertion sequence, has been previously described (2, 6, 7, 12, 23). IS6110 has only been detected in species belonging to the M. tuberculosis complex (M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, M. africanum, and M. microti) which present this sequence in multiple copies. In the classical human M. tuberculosis variant, the IS6110 element is usually present in 8 to 20 copies. In M. bovis strains the IS6110 element is present in two to six copies (4, 5, 24–26). Only M. bovis BCG has a single copy of IS6110, as has been demonstrated in many studies using restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns (12, 13, 22).

The aim of this work was to evaluate the possible application of the PCR technique to the diagnosis of tuberculosis in live cattle. PCR analyses of biological samples such as milk, nasal swabs, and lymph node aspirates taken from animals with known skin test reactions are described. PCR analysis was also performed using tissue specimens from slaughtered skin-test-positive animals to confirm our results. The sensitivity and specificity of PCR and nucleic acid hybridization methods were compared with those of the skin test. The results indicate that these methods could become useful diagnostic tools especially for the large-scale screening of cattle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycobacterial cultures.

The following mycobacterial reference strains were obtained from the collections of the Pasteur Institute (Paris, France): M. bovis (B7292), M. tuberculosis (140010002IP), M. avium (140310001IP), M. chelonae (140420003IP), M. phlei (141300001IP), and M. fortuitum (140410001IP). M. paratuberculosis (ATCC 19698) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. All the mycobacterial cultures were maintained on Lowenstein-Jensen agar slopes and were grown in 100 ml of Dubos medium enriched with 10% Dubos medium albumin and 5% equine serum (Microbiological Diagnostici). The cultures were incubated for 25 to 28 days at 37°C. M. bovis was isolated routinely from sacrificed bovines submitted to the Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale della Sicilia in Palermo, Italy, where it was identified by conventional testing which included growth rate, gross and microscopic colony morphologies, and pigmentation of cultures and tests for niacin, catalase, nitrate reduction, and urease.

Preparation of mycobacterial DNA.

Large-scale DNA extractions were performed as described by B. C. Ross et al. (18) with some modifications. Mycobacterial cultures in 100 ml of Dubos medium were centrifuged for 15 min (3,500 × g, 4°C) in a GPR Beckman centrifuge. The pellet was washed twice with STE buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) and suspended in 4 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM EDTA [pH 8.5] 15% [wt/vol], 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]). Lysozyme (Boehringer Mannheim) was added to a final concentration of 2 mg/ml. The mixture was incubated in a thermostatic bath at 37°C for 3 h. Proteinase K (Sigma Chemical Co.) was added to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml, and incubation was continued at 37°C for 1 h. After two rounds of phenol-chloroform extraction, the DNA was precipitated with ammonium acetate (final concentration, 0.3 M), overlaid with 2.5 volumes of ice-cold ethanol, and mixed by inversion (19). Genomic DNA was recovered by centrifugation at 13,800 × g for 30 min, washed with 70% (vol/vol) ethanol, and suspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]). The DNA was incubated with RNase A (Boehringer Mannheim) (100 μg/ml) at 37°C for 1 h and further purified with another phenol-chloroform extraction and precipitation step. The concentration and purity of extracted DNA were calculated by readings of A260 and A280 with a Hitachi U-1100 spectrophotometer. The reagents were supplied by Sigma Chemical Co.

DNA purification from bovine samples.

DNA was extracted from samples of lymph node aspirates, milk, and nasal swabs from live animals and from lymph node, lung, and udder tissues taken from slaughtered animals. The extraction from the live animal samples was performed with a QIAamp Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN). Nasal swabs were washed in 0.5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline solution. A total of 200 μl of each sample was incubated with Proteinase K in 1 volume of a suitable lysis buffer, and then the enzyme was inactivated by heating to 70°C for 10 min. Ethanol (0.525 volumes) was added, and the mixture was applied onto a QIAamp spin column. After two rounds of washing, the DNA was eluted with 200 μl of the supplied buffer preheated to 70°C.

After slaughter, DNA extraction from tissue samples was performed by lysis with chaotropic reagent in guanidinium thiocyanate (GuSCN) (Eastman Kodak Company), as described by Boom et al. (1). A small piece of tissue, about 25 mg, was lysed in 900 μl of GuSCN-containing lysis buffer (120 g of GuSCN in 100 ml of 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.4] to which 20 ml of 36 mM EDTA [pH 8]–2% [wt/vol] Triton X-100 was added) with 40 μl of diatom suspension (Sigma Chemical Co.). The diatom-DNA complexes were rapidly collected by centrifugation at 12,500 × g for 30 s in a Beckman microcentrifuge. The pellet was washed twice with 1 ml of GuSCN-containing washing buffer (120 g of GuSCN in 100 ml of 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.4]), twice with 1 ml of 70% (vol/vol) ethanol, and once with 1 ml of acetone. After draining at 56°C for 10 min, the DNA was eluted with 100 μl of TE buffer preheated to 56°C.

DNA amplification by PCR.

The target DNA for amplification was a 580-bp fragment of IS6110, an insertion sequence-like element currently used to identify members of the M. tuberculosis complex.

The primers used were the oligonucleotides 295 up (5′-dGGACAACGCCGAATTGCGAAGGGC-3′) and 851 down (5′-dTAGGCGTCGGTGACAAAGGCCACG-3′), which correspond to base pairs 295 to 318 and 851 to 874 of the IS6110 insertion element, respectively. The oligonucleotide sequence was chosen because of its GC content by using the Mac-Vector 5.0 program sequence analysis software (Oxford Molecular Group).

To generate a sequence-specific probe, we designated an amplicon-nested PCR product of 182 bp from the amplified 580-bp fragment. It was obtained by using primer 505 up (5′-dACGACCACATCAACCGGG-3′) and primer 669 down (5′-dGAGTTTGGTCATCAGCCG-3′), which correspond to base pairs 505 to 523 and 669 to 686, respectively. All the oligonucleotides were supplied by Cruachem Ltd. (Glasgow, United Kingdom). PCR amplification was carried out in 100-μl reaction mixtures containing (final concentrations) 2.0 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 9.3], 0.01% Triton X-100, 200 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 200 nM each primer, 72 μl of template DNA solution, and 2.5 U of DNA Taq polymerase (Promega). The reactions were performed in an automated thermal cycler (Mini Cycler; MJ Research, Inc.). The conditions were set as follows: denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 65°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min. A 7-min extension period at 72°C was added after 30 cycles. A positive control containing 10 ng of M. bovis (B/29292) DNA and a negative control, without template DNA, were included.

Electrophoresis.

Purified DNA and PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis through 0.8 and 1.5% neutral agarose gels, respectively, containing 0.1 μg of ethidium bromide (Bio-Rad Laboratories)/ml in TBE buffer (0.089 M Tris-HCl, 0.089 M boric acid, 0.002 M EDTA). The gels were visualized under UV light with a transilluminator (UV-GENTM; Bio-Rad Laboratories) and photographed with Polaroid 667 film. The DNA markers used were λ-HindIII or ladder 100 (Pharmacia).

Cloning and sequencing of the specific DNA probe.

The DNA probe, originated by PCR, was cloned by using a TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). The recombinant plasmid was obtained by ligation of 50 ng of pCR 2.1 vector with 10 ng of fresh PCR product. This plasmid was employed to transform INVαF′ One Shot competent cells. Briefly, 2 μl of 0.5 M β-mercaptoethanol and 2 μl of the ligase reaction product were added to 50-μl vials of frozen cells. After 30 min on ice, the cells were heat shocked for 30 s in a 42°C water bath and incubated in 250 μl of purchased SOC medium at 37°C for 1 h with rotary shaking at 225 rpm. Aliquots of 50 and 200 μl from each transformation were spread on Luria-Bertani agar plates containing 50 μg of ampicillin/ml and X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside). The plates were incubated for 18 h at 37°C. The picked colonies were grown overnight in 20 ml of Terrific Broth. The nucleotide sequence of the cloned fragment was determined by using pCR 2.1 primer with the Sequenase kit from USB (20).

DNA labeling of the 182-bp DNA probe.

The 182-bp amplified fragment was labeled with digoxigenin-dUTP by using a DIG DNA Labeling Kit (Boehringer Mannheim) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. For each reaction 60 ng of DNA was labeled at 37°C for 2 h and employed in hybridization.

Dot blot assay.

The amplified DNA was denatured for 5 min at 100°C and kept on ice. Samples of 5 μl were spotted on a positively charged nylon membrane (Boehringer Mannheim) and fixed by UV exposure. The blots were treated with 0.4 M NaOH for 3 min and neutralized with 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) for 3 min.

Hybridization and detection.

The filter was hybridized at 65°C overnight in an incubation bag. The prehybridization mix consisted of 4× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) 5× Denhardt solution (2% Ficoll, 2% albumin, bovine fraction V, 2% polyvinylpyrrolidone), and 1% SDS. About 4 ml of hybridization solution was used for the 100-cm2 membrane. The hybridization solution contained 15 ng of the freshly denatured (10 min, 100°C) digoxigenin-dUTP-labeled 182-bp probe/ml. After incubation the membrane was washed twice in 1× SSC–1% SDS (100 ml/100-cm2 membrane) for 15 min and twice in 1× SSC–0.1% SDS at 65°C for 15 min. The presence of a digoxigenin-labeled probe was detected by using an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibody and CSPD substrate according to the instructions for the DIG-dUTP-DNA detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim). The chemiluminescent signal was revealed on X-ray film (X AR Omat; Kodak) after exposure for 20 min at room temperature.

RESULTS

Specificity and sensitivity of PCR.

The primers 295 up and 851 down were used for PCR analysis of purified DNAs of the eight mycobacterial species listed in Materials and Methods. A 580-bp product was found only in mycobacteria belonging to the M. tuberculosis complex, as was confirmed by dot blot analysis (data not shown).

The sensitivity of the PCR was determined by adding mixtures containing decreasing amounts of M. bovis DNA in a range between 20 ng and 1 fg to the reaction vials. One femtogram of DNA could be amplified and, in dot blot analysis, gave a detectable hybridization signal with the 182-bp probe (data not shown).

Detection of M. bovis DNA in different biological samples.

During a 12-month period, 100 cattle were tested by PCR using DNA extracted from lymph node aspirates, milk, and nasal swabs. All 60 of these animals which were skin test positive were slaughtered, and DNA was purified from samples of lymph node, lung, and udder tissues. PCR was carried out using these DNA samples to confirm the diagnosis of M. bovis infection.

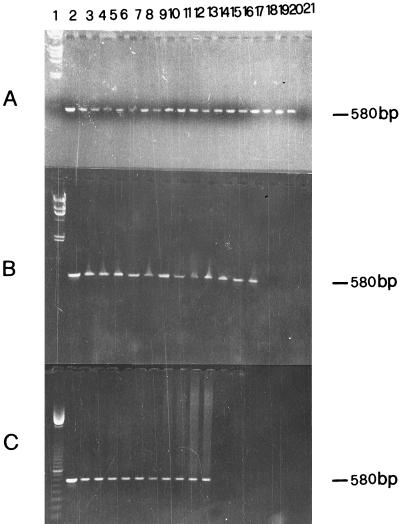

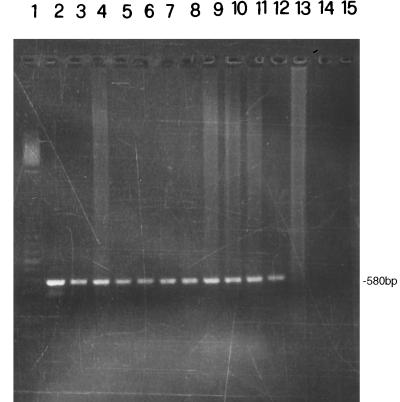

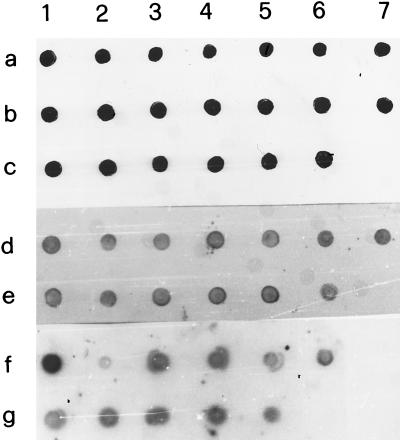

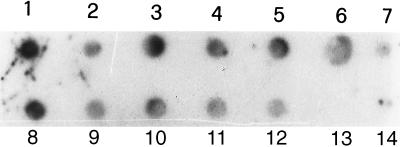

Gel electrophoresis analysis of representative examples of PCR products is shown in Fig. 1. The 580-bp fragment of IS6110 was amplified in all purified DNA from nasal swabs (Fig. 1A), milk (Fig. 1B) and lymph node aspirates (Fig. 1C) as demonstrated by comparison with the positive control containing 10 ng of M. bovis DNA (Fig. 1, lane 2). Successful amplification of IS6110 fragments was also obtained with DNA extracted from tissue specimens. Figure 2 shows results for four samples each of lymph node, lung, and udder tissues. These tissue samples were taken postmortem from four cows that were also used for the analysis shown in Fig. 1 (lanes 3 to 6). Hybridization of the 182-bp probe with amplified DNA from specimens of nasal swabs, milk, and lymph node aspirates is shown in Fig. 3. The dot blot of amplified DNA from lymph node, lung, and udder tissues is shown in Fig. 4, and only the last spot, corresponding to the sample in lane 14 of Fig. 2, gave no hybridization signal. Amplification of the 580-bp fragment which was not detectable by gel analysis (Fig. 2, lane 13) was proved by dot blot hybridization. These results show the greater sensitivity of dot blot hybridization compared to gel electrophoresis.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of PCR-amplified 580-bp fragment by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. DNA was extracted from nasal swab (A), milk (B), and lymph node aspirate (C) samples. Procedures for DNA preparation and PCR amplification, and sequences of primers used are given in the text. A total of 70 μl of PCR products was analyzed. Lane 1, λ phage digested with HindIII (panels A and B) or ladder 100 (panel C) as a DNA molecular size marker; lane 2, positive control amplified from 10 ng of M. bovis DNA. (A) Lanes 3 to 20, 580-bp amplified fragments from nasal swab samples from skin-test-positive cows; lane 21, control without mycobacterial DNA. (B) Lanes 3 to 14, 580-bp amplified fragments from milk samples from skin-test-positive cows; lane 15, control without mycobacterial DNA. (C) Lanes 3 to 12, 580-bp amplified fragments from lymph node aspirate samples from skin-test-positive cows; lane 13, control without mycobacterial DNA.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of PCR-amplified 580-bp fragment by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis. Procedures for DNA preparation and PCR amplification and sequences of primers used are given in the text. DNA was extracted from tissues of four skin-test-positive cows that were also used for the experiment described in Fig. 1 (lanes 3 to 6). Lane 1, ladder 100 as a DNA molecular size marker; lane 2, target DNA amplified from 10 ng of M. bovis DNA; lanes 3 to 6, DNA from lymph node tissue; lanes 7 to 10, DNA from lung tissue; lanes 11 to 14, DNA from udder tissue; lane 15, control without mycobacterial DNA.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of PCR products by dot blot hybridization with 11-dUTP-labeled 182-bp probe. Procedures for PCR amplification, sequences of primers used, and description of cloning and sequencing of probe are given in the text. Samples are the same as those used in the experiment described in the legend to Fig. 1. Spot 1a, target DNA amplified from 10 ng of M. bovis DNA; spots 2a to 6c, PCR products from nasal swab samples; spot 7c, control without mycobacterial DNA; spot 1d, target DNA amplified from 10 ng of M. bovis DNA; spots 2d to 6e, PCR products from milk samples; spot 7e, control without mycobacterial DNA; spot 1g, target DNA amplified from 10 ng of M. bovis DNA; spots 2g to 5g, PCR products from lymph node aspirate samples; spot 6g, control without mycobacterial DNA.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of PCR products by dot blot hybridization with 11-dUTP-labeled 182-bp probe. Procedures for PCR amplification, sequences of primers used, and description of cloning and sequencing of probe are given in the text. Samples are the same as those used for the experiment described in the legend to Fig. 2. Spot 1, target DNA amplified from 10 ng of M. bovis DNA; spots 2 to 5, PCR products from lymph node tissue; spots 6 to 9, PCR products from lung tissue; spots 10 to 13, PCR products from udder tissue; spot 14, control without mycobacterial DNA.

Samples were deemed positive when the 580-bp fragment hybridized with the 182-bp probe in the dot blot test. Samples were considered negative when no detectable signal was found in the dot blot hybridization with the labeled probe.

We calculated the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of the combined PCR-dot blot test performed for the 60 animals that were skin test positive. For these calculations we used the results obtained by PCR using both samples from live cattle and tissue samples as a “gold standard.” PCR analysis using 54 milk samples and 49 lymph node aspirates gave the 100% values for sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values. PCR using 50 nasal swabs shown high specificity (100%) but a low sensitivity (58%); the positive predictive value was also 100% while the negative predictive value was only 28% (Table 1). The lower values for nasal swabs account for the total sample values of 74, 100, 100, and 35% for sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values, respectively (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Detection of M. tuberculosis complex by PCR using nasal swabs, milk, and lymph node aspirates taken from live skin-test-positive cattle versus PCR detection using tissue samples from slaughtered cattle

| Kind of sample | Result for PCR-tested biological samples | Result (no.) for PCR-tested tissue samples

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | ||

| Nasal swab | Positive | 25 | 0 | 25 |

| Negative | 18 | 7 | 25 | |

| Total | 43 | 7 | ||

| Milk | Positive | 47 | 0 | 47 |

| Negative | 0 | 7 | 7 | |

| Total | 47 | 7 | ||

| Lymph node aspirate | Positive | 42 | 0 | 42 |

| Negative | 0 | 7 | 7 | |

| Total | 42 | 7 | ||

TABLE 2.

Detection of M. tuberculosis complex by PCR using samples taken from live skin-test-positive cattle versus PCR detection using tissue samples from slaughtered cattle

| Result for PCR-tested samples from live cattle | Result (no.) for PCR-tested tissue samples

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Positive | 114 | 0 | 114 |

| Negative | 39 | 21 | 60 |

| Total | 153 | 21 | |

As shown in Table 3, we compared the results of visual inspection with those of PCR detection using tissue samples. We observed 43 tissue specimens with typical lesions and 10 showing no visible lesions during the veterinary inspection; all of these samples were PCR positive. The remaining seven skin-test-positive cows were negative by PCR-dot blot hybridization for all samples examined. We calculated the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for visual inspection after slaughtering as being 81, 100, 100, and 58%, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Detection by visual inspection of typical M. tuberculosis complex lesions in tissue samples taken from slaughtered skin-test-positive cattle versus PCR detection using the same tissue samples

| Type of tissue sample | Result (no.) for PCR-tested tissue samples

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | |

| With lesion | 43 | 0 | 43 |

| Without lesion | 10 | 7 | 17 |

| Total | 53 | 7 | |

The main goal of this study was to check M. bovis infection in cattle with high precision and compare the results with those from skin testing. We obtained interesting results especially in the cases of dubious reactivity to the skin test and when a nonspecific reaction occurred in animals in the absence of typical clinical manifestations. This happened in seven skin-test-positive animals that, submitted to veterinary inspection, had not shown the typical M. bovis lesions. Two of these cows were tested by PCR using milk, lymph node aspirates, lymph node tissue, and lung tissue. One of these cows was positive to the skin test, while the other showed a low reaction; however, being officially positive, both were slaughtered. The skin-test-positive cow was PCR and dot blot negative, while the results for the cow with a dubious reaction were negative for all of the samples tested (data not shown).

To establish if our test could detect false skin-test-negative subjects, we examined 40 animals considered officially M. bovis free. Of these a group of seven bulls and a group of seven cows on two different farms gave interesting results. All the animals had been negative to the skin test performed 1 year before our investigation. The dot blot hybridization of amplified DNA samples from the bull lymph node aspirates and cow milk showed that all of these animals were positive, except one bull (data not shown). One week later the animals were retested by the skin test and were examined clinically, and all results were negative. However, on the basis of our results, the skin test was repeated 6 months after our test, and again all the results were negative. These animals are considered officially M. bovis free.

In Table 4 the results from the 100 animals tested by PCR during the period of our investigation are summarized. Of the 40 skin-test-negative animals, 19 were confirmed by PCR, while 21 resulted positive in at least two of the tests performed using milk, lymph node aspirates, and nasal swabs.

TABLE 4.

Correlation between PCR-dot blot and skin testa

| PCR-dot blot result | Result (no.) by skin test

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk

|

Lymph node aspirate

|

Nasal swab

|

Tissue with lesion

|

Tissue without lesion

|

Total

|

|||||||

| + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | |

| + | 47 | 11 | 42 | 10 | 25 | 13 | 43 | 10 | 53 | 21 | ||

| − | 7 | 17 | 7 | 18 | 25 | 13 | 7 | 7 | 19 | |||

+, positive; −, negative.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here represent a successful attempt to satisfy the need for a more sensitive, specific, and rapid test for the diagnosis of tuberculosis in cattle. In particular, the utility of PCR as a tool to test M. bovis infection in biological samples taken from live animals was studied. The farms tested in this study were randomly selected in Sicily, and the specimens examined were taken and kept in sterile conditions to avoid contamination between different cows from the same farm. We performed PCR using samples of milk, lymph node aspirates, and nasal swabs from 100 cows and on tissue samples, taken after slaughter, 60 skin-test-positive animals. IS6110 was chosen as the target sequence for the PCR test because it is specific for mycobacteria belonging to the M. tuberculosis complex, and the results obtained were in accordance with those of other authors (12, 14, 23). Amplification of the 580-bp fragment, revealed by detection of the 182-bp hybridized probe, can reveal as little as 1 fg of DNA, corresponding to one mycobacterial genome (14). Excellent sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values were found for the PCR-dot blot test performed using milk samples and lymph node aspirates. So this kind of sample could be considered useful in the screening for tuberculosis in cattle, having a higher accuracy than the skin test. Sampling milk did not present difficulties, and we obtained samples from 54 of the 60 skin-test-positive cows (the remaining 6 were pregnant). A total of 87% of these milk samples were positive by PCR, and the results for the “no visible lesion reactors” were negative. This latter result was also confirmed by nasal swab and lymph node aspirate examination, revealing 12% false positives to the skin test. It was hypothesized that this highly sensitive technique could be employed to diagnose early tuberculosis in cattle and to prevent the spread of infection. The nasal swab analysis only permitted identification of 58% of infected animals and 28% of noninfected cattle. Our results agree with known clinical data that report few cases of open tuberculosis in cattle. Nevertheless PCR using nasal swabs has high specificity and positive predictive value and could be used together with PCR using other samples from the same subjects, giving a clear sign of airborne contamination within herds. Taking nasal swabs is easier and quicker than other more-invasive sampling methods. It is therefore very useful particularly in the case of generalized tuberculosis in which it is known that some animals may fail to respond to skin testing while M. bovis may be present in nasal fluid.

Another significant fact was the 81% sensitivity for the visual inspection test versus PCR using tissue samples. The absence of macroscopic lesions does not exclude the presence of early infection. On the other hand the 58% negative predictive value indicates that a significant number of nonlesion reactors are slaughtered erroneously. The easy recognition of typical tuberculosis lesions in slaughtered cattle gives 100% specificity and positive predictive value.

Only 28 milk samples, 30 lymph node aspirates, and 26 nasal swabs from 33 cows and 7 bulls that were negative to the skin test were examined, because we could take only one or two kinds of sample from each animal. In fact on many farms, officially free from infection, complete sampling was not possible. A total of 11 milk, 10 lymph node aspirate, and 13 nasal swab samples were positive by PCR, and the subjects for which at least two samples were positive by PCR were deemed positive. The data suggest that 52% of the skin-test-negative animals tested in our study may be false negatives. The low sensitivity and specificity of the bovine skin test (8, 9, 16, 21) is the cause of decreased efficacy in eradication campaigns and leads to a greater risk in public health programs and also to economic losses in the cattle industry.

The specific PCR analysis reported here can be performed on biological samples easily taken from animals on the farm. The simplicity of its application is typified by the fact that milk samples and lymph nodes aspirates, which give precise results, provide excellent material for diagnosis. The method is rapid, requiring only 48 to 72 h from sampling for the detection of amplified DNA in dot blot hybridization. It may therefore be very useful to do PCR in parallel with the officially approved skin test, especially in the case of dubious reactions, anergy, or when in the presence of cross-reactivity with correlated antigenic determinants. Moreover, it may be possible to use this test in epidemiological studies aimed at determining the prevalence of bovine tuberculosis in areas in which the disease has not been eradicated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by grants from the Italian Ministry of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boom R, Sol C J A, Salimans M M M, Jansen C L, Wertheim-van Dillen P M E, van der Noordaa J. Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:495–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.495-503.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brisson-Noel A, Gicquell B, Lecossier D, Levyfrebault V, Nassif X, Hance A J. Rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis by amplification of mycobacteria DNA in clinical samples. Lancet. 1989;4:1069–1071. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarridge J E, Shawar R M, Shinnick T M, Plikaytis B. Large-scale use of polymerase chain reaction for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a routine mycobacteriology laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2049–2056. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2049-2056.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins D M, Erasmuson S K, Stephens D M, Yates G F, De Lisle G W. DNA fingerprinting of Mycobacterium bovis strains by restriction fragment analysis and hybridization with insertion elements IS1081 and IS6110. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1143–1147. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.5.1143-1147.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cousins D V, Williams S N, Ross B C, Eliis T M. Use of repetitive element isolated from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a new tool for epidemiological studies of bovine tuberculosis. Vet Microbiol. 1993;37:1–17. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(93)90178-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenach K D, Cave M D, Bates J H, Crawford J T. Polymerase chain reaction amplification of a repetitive DNA sequence specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:977–981. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.5.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenach K D, Sifford M D, Cave M D, Bates J H, Crawford J T. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in sputum samples using a polymerase chain reaction. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:1160–1163. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francis J, Seiler R J, Wilkie I W, O’Boyle D, Lumsden M J, Frost A J. The sensitivity and specificity of various tuberculin tests using bovine PPD and other tuberculins. Vet Rec. 1978;103:420–425. doi: 10.1136/vr.103.19.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardner I A, Hird D W. Environmental source of mycobacteriosis in California swine herd. Can J Vet Res. 1989;53:33–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardie R M, Watson J M. Mycobacterium bovis in England and Wales: past, present and future. Epidemiol Infect. 1992;109:23–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawkey P M. The role of polymerase chain reaction in diagnosis of mycobacterial infections. Rev Med Microbiol. 1994;5:21–32. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hermans P W M, van Soolingen D, Dale J W, Schuitema A R J, McAdam R A, Catty D, van Embden J D A. Insertion element IS986 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a useful tool for diagnosis and epidemiology of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2051–2058. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.2051-2058.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hermans P W M, van Soolingen D, Bik E M, de Haas P E W, Dale J W, van Embden J D A. Insertion element IS987 from Mycobacterium bovis BCG is located in a hot-spot integration region for insertion elements in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains. Infect Immun. 1990;59:2695–2705. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2695-2705.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolk A H J, Schuitema A R J, Kuijper S, van Leeuwen J, Hermans P W M, van Embden J D A, Hartskeerl R A. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in clinical samples by using polymerase chain reaction and a nonradioactive detection system. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2567–2075. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.10.2567-2575.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neill S D, Hanna J, Mackie D P, Bryson T G D. Isolation of Mycobacterium bovis from the respiratory tracts of skin-test-negative cattle. Vet Rec. 1992;131:45–47. doi: 10.1136/vr.131.3.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neill S D, Cassidy J, Hanna J, Mackie D P, Pollock J M, Clements A, Walton E, Bryson D G. Detection of Mycobacterium bovis infection in skin-test-negative cattle with an assay for bovine interferon-gamma. Vet Rec. 1994;135:134–135. doi: 10.1136/vr.135.6.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pao C C, Yen T S, You J B, Maa J S, Fiss E H, Chang C H. Detection and identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA amplification. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1877–1880. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.1877-1880.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross B C, Raios K, Jackson K, Dwyer B. Molecular cloning of a highly repeated DNA element from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its use as an epidemiological tool. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:942–946. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.4.942-946.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seiler R J. The non-diseased reactor: considerations on the interpretation of screening test results. Vet Rec. 1979;105:226–228. doi: 10.1136/vr.105.10.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szewzyk R, Svenson S B, Hoffner S E, Bölske G, Wahlström H, Englund L, Engvall A, Källenius G. Molecular epidemiological studies of Mycobacterium bovis infections in humans and animals in Sweden. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3183–3185. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3183-3185.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thierry D, Brisson-Noël A, Vincent-Lévy-Frébault V, Nguyen S, Guesdon J-L, Gicquell B. Characterization of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis insertion sequence, IS6110, and its application in diagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2668–2673. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.12.2668-2673.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Soolingen D, de Haas P E W, Haagsma J, Eger T, Hermans P W M, Ritacco V, Alito A, van Embden J D A. Use of various genetic markers in differentiation of Mycobacterium bovis strains from animals and humans and for studying epidemiology of bovine tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2425–2433. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2425-2433.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Soolingen D, Hermans P W M, de Haas P E W, van Embden J D A. Insertion element IS1081-associated restriction fragment length polymorphisms in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex species: a reliable tool for recognizing Mycobacterium bovis BCG. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1772–1777. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1772-1777.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Soolingen D, Hermans P W M, de Haas P E W, Soll D R, van Embden J D A. Occurrence and stability of insertion sequences in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: evaluation of an insertion sequence-dependent DNA polymorphism as a tool in the epidemiology of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2578–2586. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2578-2586.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]