Abstract

In 2022, a case of paralysis was reported in an unvaccinated adult in Rockland County (RC), New York. Genetically linked detections of vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (VDPV2) were reported in multiple New York counties, England, Israel, and Canada. The aims of this qualitative study were to: i) review immediate public health responses in New York to assess the challenges in addressing gaps in vaccination coverage; ii) inform a longer-term strategy to improving vaccination coverage in under-vaccinated communities, and iii) collect data to support comparative evaluations of transnational poliovirus outbreaks. Twenty-three semi-structured interviews were conducted with public health professionals, healthcare professionals, and community partners. Results indicate that i) addressing suboptimal vaccination coverage in RC remains a significant challenge after recent disease outbreaks; ii) the poliovirus outbreak was not unexpected and effort should be invested to engage mothers, the key decision-makers on childhood vaccination; iii) healthcare providers (especially paediatricians) received technical support during the outbreak, and may require resources and guidance to effectively contribute to longer-term vaccine engagement strategies; vi) data systems strengthening is required to help track under-vaccinated children. Public health departments should prioritize long-term investments in appropriate communication strategies, countering misinformation, and promoting the importance of the routine immunization schedule.

Keywords: childhood vaccination, New York, poliovirus, qualitative research, vaccine engagement

Introduction

In July 2022, genetically linked detections of vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (VDPV2) were identified in wastewater from the United States, United Kingdom (UK), and Israel, and in September 2022, they met the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of circulating VDPV2 (cVDPV2) [1, 2]. These countries were subsequently included by the WHO as ‘infected’ with cVDPV2 in November 2022, alongside many lower- and middle-income countries [3]. The same genetically linked cVDPV2 was also detected in Canada in specimens collected in August 2022 [4]. Alarm has been raised that circulation of VDPVs might emerge in high-income countries that do not routinely use live oral poliovirus vaccines (OPV), even though these countries have optimal sanitation and public health infrastructure, and that maintain high overall polio vaccination coverage by using only inactivated polio vaccines (IPV) [5]. Global polio eradication efforts still rely on use of OPV due to logistics, cost, and passive immunization. Yet, the attenuated poliovirus contained in the live OPV has the risk of significantly mutating if allowed to circulate widely among un- or under-vaccinated individuals. Occasionally, these mutations can precipitate the return of neurovirulence in the virus and result in paralysis in unvaccinated individuals [6]. Hence, use of OPV has been broadly discontinued in higher-income countries that have eliminated polio [6].

Public health agencies in the United States and UK have stressed that the risk of contracting polio in their countries is extremely low for people who are vaccinated with IPV according to the recommended immunization schedules, but that areas and populations with lower-level vaccination coverage will remain vulnerable to infection, transmission, and ongoing circulation. Despite high overall national coverage in both countries, rates of childhood vaccination coverage can vary between communities and persistent gaps in coverage will continue to render under-vaccinated populations vulnerable to vaccine-preventable disease (VPD) outbreaks [7–10]. Addressing disparities in coverage will require appropriate policies and sustainable delivery strategies.

The aim of this qualitative assessment was to i) review immediate public health responses to the poliovirus outbreak in New York State (NYS) in August 2022, ii) determine the challenges in addressing gaps in vaccination coverage; iii) inform a sustainable longer-term strategy to improve vaccination coverage in NY; and iv) collect data to support comparative evaluations of transnational poliovirus outbreaks.

Circulating VDPV2 in NYS

A confirmed case of paralytic polio in an unvaccinated young adult without a relevant travel history for poliovirus exposure was reported by the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) and Rockland County Department of Health (RCDOH) in July 2022 [1]. Viral genotyping isolated VDPV2, and wastewater surveillance confirmed the presence of Sabin-like poliovirus type 2 or VDPV2 in multiple counties in NYS [1]. Residents and providers in Rockland County were immediately advised to ensure that children were up to date with polio vaccinations. Additionally, IPV boosters were recommended to at-risk groups. A public health emergency was declared in NYS on 9 September 2022 [11], and the United States clinical and environmental poliovirus detections met the WHO definition of cVDPV2 on 13 September 2022 [2].

The outbreak constitutes only the second identification of community transmission of poliovirus in the United States since 1979, when the country was declared polio free [1]. Routine use of OPV was replaced with an all-IPV immunization schedule in 2000 to remove all risks of vaccine-associated paralytic polio. In this outbreak, it is likely that cVDPV2 emerged in NYS following viral shedding in proximity to unvaccinated or under-vaccinated close contacts, who in turn extended transmission of VDPV2 within a large collective of people who were unvaccinated and in an area where IPV vaccination coverage is lower than the required 80–85% threshold to protect population health [1, 5].

Childhood vaccinations, including IPV, are typically available via private-sector paediatric clinics or county health departments in NYS. Children resident in NYS and who might not otherwise be vaccinated because of inability to pay may be entitled to receive all vaccines recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices via the publicly funded Vaccines for Children programme [12, 13]. In NYS, all children must receive all required doses of vaccines on the recommended schedule to attend day care and pre-kindergarten (under the age of 5) through to 12th grade (ages 17–18), or provide proof of immunity via titres (when permitted), or a medical exemption [14].

At the time that VDPV2 was isolated, coverage for 3 doses of IPV at 24 months of age in Rockland County was 60.3% compared with the 79% state average [7]. Rates vary across Rockland County (37.3%–91.3%), but the ZIP codes with the lowest-level coverage in Rockland County were in Monsey (37.3%) and Spring Valley (57.1%) [15]. Rockland County has the largest Jewish population per capita of any county in the United States (31.4% of the county population) [16]. Monsey and Spring Valley are home to a number of neighbourhoods that are exclusively Haredi Jewish (often termed ‘ultra-Orthodox’). Haredi neighbourhoods in Rockland County remain closely connected with those in other areas of NYS (NY City and Orange County) and New Jersey.

Previous outbreaks of VPD in Rockland County have primarily affected Haredi children, in part due to low vaccination coverage and importations from similarly under-vaccinated communities. Public health agencies frequently report outbreaks of VPD in areas of Jerusalem, NYS, and London that are home to large Haredi neighbourhoods [8–10, 16–18]. Studies report that vaccine uptake among Haredi populations is influenced by a range of issues, including access and convenience challenges due to larger families, a preference for delayed acceptance, and targeted activism and misinformation campaigns [17, 19]. In 2018, a measles outbreak spread in Rockland County ZIP codes with the lowest levels of vaccination coverage, and transmission was sustained in un- or under-vaccinated populations; this outbreak was associated with a larger regional, national, and international measles outbreak. As a result, the United States and Israel consequently reported the largest cases of measles in a quarter century [9, 10].

Haredi Jews form diverse movements (sub-groups) that are distinguished by ethnicity and place of origin, and differences in customs and stringencies that influence social organization and how religious law (halachah) is interpreted. Haredi Jews may be characterized as self-protective and may carefully manage encounters with the broader society [20], which can have implications for health care [18–21]. Health decisions among Haredi families may be influenced by socio-economic background, health literacy, and religious legal positions [21–24]. Engagement with healthcare services should be understood within the respective national context of health systems, but also the global circulation of information via social networks that spans Europe, North America, and Israel.

Poliovirus detections were repeatedly identified via wastewater surveillance in Rockland County and NYS between March–October 2022, indicating ongoing transmission [25]. Hence, unvaccinated children and adults in this community remained vulnerable to paralysis and were a priority in efforts to promote vaccine uptake. Understanding the context in which poliovirus spread is important to: i) address gaps in vaccination coverage and ensure targeted distribution of resources as part of public health engagement activities; ii) compare and evaluate responses to linked outbreaks reported in Israel (April 2022) and London (June 2022), in addition to detection in Canada (reported in January 2023) [4, 26, 27].

The purpose of this qualitative study was to examine what long-term and sustainable strategies for vaccine engagement in populations vulnerable to VPD outbreaks are required to support responses in the context of transnational poliovirus circulation. Vaccine engagement is premised on a relationship between public health agencies, primary care services, and populations. Vaccine engagement involves tailored, localized, and sustained dialogue to aid delivery of immunization programmes.

Methods

This qualitative study was conducted ancillary to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) epidemiologic investigation that was launched to support state and county poliovirus response efforts, at the invitation of New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) [28]. Complementing the epidemiologic investigation, this qualitative study sought to inform long-term vaccination strategies in Rockland County for related populations in the region. Fieldwork was conducted in August 2022, after the positive case detection on 21 July 2022 and prior to the declaration of a public health emergency on 9 September 2022.

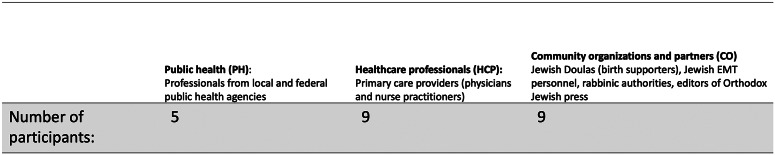

Methods consisted of 23 semi-structured in-depth interviews conducted with individual participants or in paired interviews (in person and via Zoom) and 5 clinic visits. Interview participants were recruited from professional networks and via snowball sampling and were included in the study based on their experience as public health professionals (5), healthcare professionals (9), and community organizations and partners (9) (Figure 1). Interviews lasted between 20 and 60 min and were recorded with participant consent.

Figure 1.

Description and recruitment numbers of interview participants.

Public health (PH) professionals were based in county and federal agencies. The Healthcare professionals (HCP) were based in 5 clinics that serve Jewish families in the area under study. HCP participants included a variety of professionals, such as physicians and nurse practitioners. Community organizations and partners (CO) ranged in their professional background and were interviewed as key male and female figures of influence (Figure 1). Jewish doulas and EMT were categorized as community CO because we spoke to them in their capacity as community health advocates rather than their specific care practices in childbirth or emergency care. CO represented a variety of sects within the Haredi movement. The particulars of their affiliations have been removed for anonymity.

Analysis

Interview data involved a combination of inductive and deductive analytical approaches [29]. Existing literature was used to frame the research questions, and key analytical themes were drawn directly from the data via a qualitative method termed grounded theory [29]. Emergent coding themes were reviewed and discussed extensively between BK and SM-J and refined as the results of these discussions. Findings were then organised using critical phases of the public health response with a view to informing how differences in coverage can be addressed and a longer-term strategy of vaccine engagement developed.

Findings

Results illustrate that a succession of public health challenges, locally and globally, combined with deficits in resources, meant that the county and federal public health (PH) officials involved in the polio outbreak response felt inadequately prepared to address low vaccination coverage in the affected areas. Healthcare professional (HCP) participants indicated that the poliovirus incident was not unexpected after previous local VPD outbreaks and the increase in cVDPV2 outbreaks globally. Diverse vaccine engagement and implementation activities were mobilized, but participants reported limitations in health systems. Community organizations and partners (CO) participants identified a need for investment in public health engagement to support vaccine programme delivery. Longer-term strategies to monitor vaccine uptake will require health systems strengthening.

Pre-outbreak: existing challenges to vaccine engagement

The 2018–19 measles epidemics and COVID-19 pandemic were described as milestones in understanding challenges in vaccine engagement by PH and HCP participants. During the 2018–19 measles outbreak, religious exemptions from NYS school vaccination requirements were removed, and unvaccinated children were banned from public spaces (including schools) that were intended for gathering of more than 10 people in Rockland County [30]. Approximately 5 schools were fined for withholding vaccination records from the health department (PH1). However, a CO who supported the control efforts did not feel sufficiently consulted by county officials on enforcement, ‘it didn’t feel like they were taking our opinions into consideration and our thoughts of how to do things that may have made certain things easier. So, we’re just not eager to jump into work with them, period’ (CO4). The legacy of the 2018–19 measles outbreaks then had adverse implications for the polio incident response in 2022.

Activism against vaccination proliferated before and during the 2018–19 measles outbreaks and control orders, with rumours of unregistered schools being established for parents against vaccination and circulation of targeted material. One CO described being approached to lease their private building and re-purpose it as an unregistered school for children to evade vaccination requirements. As early as 2017, Haredi neighbourhoods in the United States were targeted by an organization named PEACH (Parents Educating and Advocating for Children’s Health), which portrays itself as a grassroots Haredi effort to promote ‘vaccine choice’ among parents [19, 31]. Their pamphlet, the ‘Vaccine Safety Handbook: An Informed Parent’s Guide,’ was cited by one HCP as a key source of disinformation that has influenced vaccine decisions among parents in their clinic:

‘The turning point was the PEACH magazine. That’s when it [non-vaccination or delayed vaccination] became popular. I think the trickle-down effect from that has lasted for years. I think a lot of people got very swept up in the propaganda of that, and that became the truth. So, we spend all day, every day, fighting against things that have been passed down from that time’ (HCP5).

Opportunities to develop vaccine engagement strategies following the 2018–19 measles outbreaks, however, were derailed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Rates ‘did increase for MMR. And then 4 months later COVID hit, so we couldn’t measure well what was done. That was our moment to try and figure out where we were and COVID hit and everything got shut down’ (PH1).

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 impacted uptake and delivery of childhood vaccinations. Misinformation and questions of trust, too, were amplified:

‘I think that COVID really affected uptake of vaccines twofold […] it was just increased misinformation and less ability for people to access care. I have learned that there is a very strong anti-vax group in this county. They make robocalls, they have that kind of resources, and they are very incessant. I think this is a very vulnerable community that’s easy to target. There is a large mistrust of the government’ (PH2).

Questions around the COVID-19 vaccination, as a rapidly developed and implemented campaign, had negatively impacted parental engagement with routine vaccinations:

‘There has been some damage towards vaccination because of COVID, it politicised vaccines and there was misinformation about quality and effectiveness […] Politics has done extreme damage to medicine, the average individual becomes confused of what they should or shouldn’t do. COVID has done damage, but we can come back from that’ (CO6).

All HCP acknowledged issues of refusal and trust following the COVID-19 pandemic, but consistently described deferral as a major cause for low vaccination coverage by 24 months of age:

‘The biggest issue, especially in the past 5 years, has been deferring vaccinations until an older age. So rather than start at the typical 2 months, some people want to start at around 6 months or 1 year. Some people want to vaccinate just when the school requires them to’ (HCP4).

Rather than an issue of broadscale vaccine refusal, Haredi parents may deliberate over the timing of when to vaccinate children.

Outbreak

Following an unrelated vaccine derived poliovirus type 3 (VDPV3) incident in Israel in March 2022 (prior to the subsequent VDPV2 incident in Israel in April), PH sought to highlight the risk of spread from Israel to NYS due to lower-level vaccination coverage in New York’s Haredi population. The RCDOH distributed alert letters to the public via paediatric clinics, ‘because we knew of our low immunization rates, and frequent travel to and from Israel, especially going into Passover’ (PH2). HCP, too, were concerned about the potential for spread in linked populations, as occurred with measles in 2018–19:

‘I did start discussing it with parents who were not vaccinating or deferring vaccinations at that point, because even if it started outside of the country, in England or in Israel, it’s only a matter of time that it comes here through travel’ (HCP4).

Field team response

After the positive case identification in Rockland County, public health agencies expanded clinical and wastewater surveillance into neighbouring NYS counties and NYC to understand size and spread of the outbreak, intensified outreach to under-vaccinated children, and initiated communication and vaccination campaigns. The CDC field team assisted RCDOH by looking through provider records for unvaccinated children and invited parents through letters or phone calls to visit their paediatrician for routine immunization catch-up. Amidst pressures on resources, PH valued the technical support offered to them and to paediatricians:

‘At least from my perspective, the work that needed to be done was really to go through the providers to contact their patients. And that’s a lot of work, right? Like call your patients in, call and talk to each and every provider. That’s a lot of work which we don’t have the manpower for. Chronically, public health in the United States is under-funded’ (PH2).

Communications and engagement

Vaccination and sanitation engagement activities included infographics; handwashing posters for children and adults; public letters in English and Yiddish addressed to residents from the CDC Director and NYSDOH Commissioner of Health, and separately from the RCDOH Commissioner of Health; and a public letter signed by rabbinic authorities (in English and Hebrew). An external agency was commissioned to produce infographics in English, Yiddish, Spanish and Creole, as an attempt to engage with a range of communities within the county at risk of paralysis due to low vaccination coverage (Supplementary material S1).

The infographic was endorsed by select healthcare providers and the local Hatzolah division (an Orthodox Jewish emergency medical technician [EMT] service). The cautious use of the Internet among Haredi populations meant that print materials were considered crucial for public engagement, ‘I think the circulation of materials is essential here, especially since we can’t really rely on social media and the internet to reach all groups’ (PH2). The infographic was revised and re-issued following the need for clarity in messaging surrounding transmission routes, and incorrect interpretations that VDPV2 was spreading (rather than being detected) via the sewage system (Supplementary material S2):

‘The first infographic came out with the wastewater graphic; I did not like it and I had them change it. Somebody said to me over Shabbos, ‘well I don’t go anywhere near wastewater so I’m safe’ […] Nobody understands what the heck wastewater is’ (CO3).

A key message of the infographic was the historical impact of immunization in poliovirus prevention efforts, ‘what matters is to show the timeline of cases, immunization, cases drop’ (CO3). However, an HCP viewed the infographic as being information-dense and unsuitable for quick synthesis of key messages in clinic waiting rooms:

‘They won’t stop to look at it when they come in with four kids. ‘The only protection is immunization’ in the red box shouldn’t be at the bottom because people, if they don’t read the information, won’t get the take home message’ (HCP2).

Vaccination response

Poliovirus-containing vaccines were delivered via paediatric primary-care clinics and RCDOH POD sites. A total of 240 IPV doses were administered by RCDOH on-site and at off-site polio PODS in August 2022, though uptake data are not disaggregated by population. During the study period, RCDOH held 2 point-of-distribution (POD) vaccination clinics in the Spring Valley ZIP code, on Wednesday 17 August (13:00–16:00 in a centre for family planning services) and Wednesday 24 August (15:00–18:00 in the Martin Luther King Multi-Purpose Center, which serves diverse communities) [32]. Uptake among this target group was low according to PH participants, but past public health evaluations indicate how appropriate, accessible, and convenient clinic arrangements serve as important enablers to vaccination for Haredi parents with larger-than-average family sizes [17]. Appropriate modes of advertising were considered crucial:

‘We’ll send out our fliers electronically […] My other colleagues will come through town and put posters up in laundromat, libraries, stores. The way I see it is, yes, we have everything up electronically, but the community we really need to reach doesn’t use that electronic communication as efficiently, so we really do have to have posters’ (PH5).

EMT respondents felt it was the role of HCP to provide guidance about routine childhood vaccination recommendations and not the EMT. However, EMTs reported that they would consider participating in supplementary campaigns (if authorized to do so):

‘We don’t ordinarily go around saying, “Get vaccinated.” That’s not really part of what we do. To say, “vaccinate your children,” is the norm. But if it’s specific, like, “the recommendation is anybody above a certain age should get a booster,” and this is based on real information that’s going to help protect people, Hatzolah will participate in that’ (CO2).

Future goals: achieving sustainable gains in vaccination coverage

Participants across all three groups interviewed reported a need for investment in targeted vaccine engagement and suggested improvements in programme delivery and health systems strengthening to achieve sustainable gains in vaccination coverage. Their responses offer three priorities for strengthening vaccine programme activities: i) maternal engagement; ii) communications to counter misinformation; and iii) vaccine policy and data management.

Maternal engagement

Haredi women tend to consult rabbinic authorities on a range of health-related issues and interventions [21–24]. However, female CO did not expect mothers to take their dilemmas around childhood vaccines to rabbinic authorities, ‘I consult with my rabbi on a lot of different matters but I would never ask him what he thinks about vaccines’ (CO3).

PH did not perceive rabbis to be the dominant influence on women’s vaccine decisions, ‘so whether the rabbi says, ‘do this, do that,’ the women will make their own decisions about that’ (PH5). For this reason, PH were explicit that engaging directly with mothers on vaccination was important because of their decision-making power around child health:

‘It is very important to be able to have the ear of the women, because one thing has consistently been brought to my attention, that healthcare decisions are made by the mothers. And the mothers have an internal network and talk to each other’ (PH2).

Engaging rabbis in vaccine delivery strategies was not considered to be detrimental, and a public letter signed by approximately two-dozen rabbinic authorities in Rockland County was circulated to encourage parental engagement with the poliovirus response. HCP suggested that rabbinic announcements may help to encourage parents who delay vaccines to come forward, but would have little influence over Haredi parents who refused vaccines:

‘As far as hearing from rabbonim in the community, I didn’t see it helping with measles and I didn’t see it helping with mumps, for the people who are strongly anti-vaccination. So, if you have people deferring, yes it would help, but for people who are strongly anti-vax, they have this belief and nothing really helps’ (HCP4).

Rabbis themselves felt that focusing only on rabbinic authority could exclude other avenues of influence: ‘I think the media has all types of pushes that are much stronger than what the rabbis have to say’ (CO1).

CO viewed women in Haredi communities as were influential on decisions around paediatric vaccination, and hence important for vaccine engagement strategies. Women in Haredi communities may hold influential roles such as doulas, teachers, preschool leads, and wives of rabbinic authorities. Discussing the contributions of Orthodox Jewish HCP in promoting vaccine engagement in Haredi neighbourhoods, one female CO asserted:

‘When we talk about vaccines, the lack of access or confidence, it’s part of the story to talk about all the women who are doing the work and are talking about vaccines. They bring confidence […] They’re healthcare professionals but they’re also moms, and they are entrenched in their communities’ (CO5).

Communications to counter misinformation

Establishing strong information pathways into the Haredi community was considered crucial to counter misinformation that has actively targeted Haredi neighbourhoods:

‘The very first thing to do is address and block the misinformation […] then it’s about building good information and having trusted community partners that can spread that through word of mouth and through public meetings and sharing stories of survivors making these diseases real. A longer-term plan that would involve a lot of in-depth community work to identify where the fear comes from, what the fear is about and how to make it better’ (PH4).

HCP were regarded as the most influential sources of information by CO, ‘The general majority will listen to their pediatrician, so we need to try to target that population with information’ (CO6). HCP requested guidance on how to communicate poliovirus transmission risk to parents and agreed this information should be presented as coming from providers rather than public health agencies:

‘I would love to hear some easily explainable facts that we could give to explain to them how it’s passed from person to person. How they are monitoring it. What the symptoms [are]. But I sometimes wonder whether having an official CDC or Department of Health [logo] would be negative, if they would rather just have something that we could put our own letter head on’ (HCP5).

Vaccine policy and data management

All HCP described immunization rates rising by the time children reach school enrolment (age 5) due to NYS school entry requirements. HCP felt additional metrics of vaccination coverage, beyond 24 months [7], might help to determine patterns of deferral and when parents decide to accept vaccination to tailor communication messages:

‘The numbers go up tremendously, because by [age] 3 the kids are already going to school [licensed early child education facilities] […] So if you looked there, the numbers would look different’ (HCP1).

However, HCP asserted that the link between delayed uptake and school-entry requirements indicated that vaccines were not primarily valued for their ability to protect child health:

‘I think what we are trying to say is, they are doing it more for requirement purposes for entry to somewhere as opposed to preventive purposes. So, it’s reactive and not proactive’ (HCP1b).’

Issues of delay require different solutions and communications compared to vaccine refusal. Tailored vaccine engagement strategies may help to convey the role that the childhood vaccination schedule plays in preventing VPD and illness, not just as a requirement for school entry. Moreover, the idea that vaccines are solely required for school entry leaves an entire population of children less than 24 months vulnerable to infection.

HCP were frustrated by vaccine requirements for school entry that permitted proof of immunity via serology (in place of vaccination) for certain VPD of childhood [14]. They perceived such provisions as undermining the need for vaccines, ‘the health department shouldn’t be accepting titers for anything’ (HCP1).

PH staff were tasked with examining immunization records to ascertain gaps in coverage and identified data limitations in the New York Immunization Information System (NYSIIS). Under NYS Public Health Law [33], healthcare providers are required to report all immunizations administered to persons under the age of 19, along with their immunization history, to NYSDOH via NYSIIS. PH complained of inefficiencies in data searches and management, ‘I can get the date of birth and then I have to calculate the age. It’s not a very smart system. I think it’s outgrown its initial build and it needs a lot of help’ (PH3). PH staff perceived such inefficiencies in data searches and management as affecting the pace of their outbreak operations, ‘It’s a lot of leg work to get the information we need’ (PH1).

Assessing vulnerable children who remained unvaccinated or under-vaccinated may have been complicated by imperfections in health information systems. Enhancing the ability to track gaps and changes in coverage will support accurate evaluations of outbreak responses and vaccine engagement strategies.

Discussion

Social science assessments of polio control programmes are predominantly conducted in lower- and middle-income countries, which remain polio endemic or vulnerable to outbreaks [34, 35]. Polio control efforts in such places face public health challenges that are not comparable to NYS, or the countries affected by such linked cVDPV2 outbreaks, which benefit from closed sewage systems and high vaccination coverage at the national level. This is the first polio outbreak in the United States in decades, prompting questions about appropriate response measures specific to communities within the United States. Improving vaccination coverage is urgent, given under-vaccination likely facilitated local transmission and ultimately the case of paralysis in NYS. However, it is also imperative to monitor and address these vaccination coverage gaps through sustained and tailored engagement with under-vaccinated populations.

This review of poliovirus response activities demonstrates that achieving sustainable improvements in vaccination coverage in under-vaccinated populations remains a challenge for public health agencies. The spread of poliovirus underscores the importance of community-specific, regional as well as country-wide responsive vaccination programmes that depend on a significant mobilization of public health resources [36, 37]. Priorities for improving and maintaining higher coverage levels include developing vaccine engagement strategies with populations that remain vulnerable to illness from VPD and enabling efficient data management and sharing for learning at regional and international levels.

Vaccine engagement

Our research shows that investment in mothers and trusted paediatricians around the importance of routine immunization is urgently needed to improve vaccination coverage in Haredi communities in NYS.

Participants across all research clusters in this study acknowledged that Haredi mothers were critical to consult about vaccination because they are principal decision-makers on child health, as has been documented in England [21]. UNICEF consider religious leaders to be key partners in vaccine programme delivery as ‘they wield considerable social and political influence’ [38]. However, our findings suggest that Haredi women do not routinely consult with rabbinic authorities on the subject of routine childhood vaccines and rabbis themselves highlighted more powerful sources of influence over parental decision-making. Direct engagement with Haredi women on childhood vaccination is therefore crucial.

Misinformation campaigns have targeted Haredi mothers before, during, and since the 2018–19 measles outbreaks, and during the COVID-19 pandemic, in NYS, London, and Jerusalem. Public health staff perceived Haredi residents to have a lack of confidence in vaccination as a safe and effective way to protect child health. A vaccine engagement strategy produced by a collaboration between public health staff, healthcare professionals, and community partners is required to counter non-vaccination advocacy and address concerns with credible information. The input of community organisations and partners, which includes mothers and parents, is crucial to ensure the content and delivery channels are acceptable to Haredi families.

RCDOH hosted off-site polio vaccine PODs in ZIP codes vulnerable to transmission. Yet, the clinic locations and times may not have been appropriate, convenient, or accessible for Haredi parents (as indicated by the enablers to vaccination cited in the WHO Tailoring Immunisations Programme study conducted with Haredi residents of north London in 2014–16) [17]. A range of information guides on poliovirus and vaccination were produced by Orthodox Jewish health advocacy groups in NYS during the outbreak [39]. During the 2018–19 national measles outbreaks, a taskforce of American Orthodox Jewish nurses produced a myth-busting guidebook to support vaccine engagement efforts and influence relationships between parents, paediatric care providers, and public health services, which can be downloaded free of charge from the NYSDOH website [40]. This guidebook was redistributed in August 2022. Yet, vaccine engagement requires a commitment to consistently channel information about childhood vaccinations as part of a broader approach to family health messaging, not just in an outbreak. The preference for delayed uptake, as described by healthcare providers, requires particular attention to reduce the risk of susceptibility in the intervening time periods.

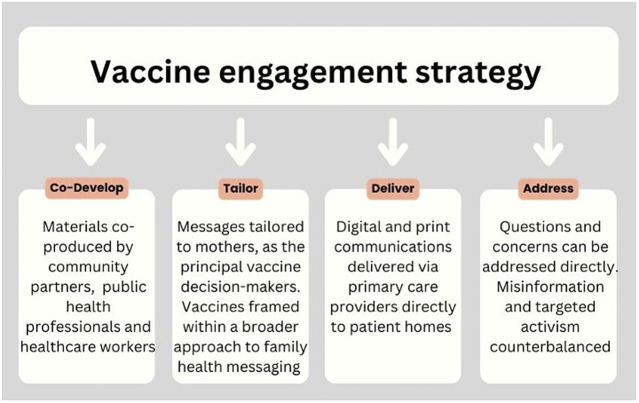

Collaboratively produced health updates can be directly and regularly channelled to Haredi mothers in print or through short, recorded phone messages. Such updates can be disseminated via primary care providers because healthcare providers are regarded as trusted sources of information, possibly more so than public health agencies (Figure 2). Appropriate community branding may help to make the health updates appear relevant to local context.

Figure 2.

Key elements of community-level vaccine engagement strategies.

Healthcare professionals were supported with labour-intensive activities such as invite-reminders (call/recall) during the outbreak response, indicating that technical support may be required to effectively increase timely uptake of vaccination as a longer-term goal. Interventions to increase confidence in timely vaccination, such as conducting post-vaccination follow-up calls or counselling parents on vaccine timeliness during medical appointments, places additional requirements on providers. Vaccine engagement activities need resource investments broadly, but also focused on the ZIP codes with the lowest levels of vaccination coverage as part of an investment in achieving sustainable gains in population-wide health protection. The circulation of poliovirus and case of paralysis is a wake-up call to implement a strategy that can be delivered and sustained through committed funding and manpower. Haredi Jewish populations in the US, UK, and Israel continue to experience a disproportionate burden of VPD [8–10, 17, 18]. Tailored and localized communication and delivery strategies are required to address this challenge proactively.

Public health relationships with community organizations and partners are important components of successful engagement programs [41]. The division of responsibilities should be explicit, and pursuit of goals should be shared to help maintain partnerships over time. Partnerships can take the form of collaborating with community agencies on communications or vaccine delivery. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Hatzolah divisions in England collaborated with public health teams to co-deliver the COVID-19 vaccine programme in 2020–21 [42]. Co-delivery models, however, operate most effectively when partners administer vaccines and public health teams hold responsibility for maintaining vaccination records [42], which are critical to tracking improvements in coverage.

Health systems and policy

Longer-term strategies will require addressing limitations in health systems, as reducing gaps in vaccination coverage requires effective data management and surveillance. As part of the outbreak response, the CDC and NYSDOH disaggregated data to assess gaps by age, delayed uptake, and when vaccines were initiated but not completed to schedule. Such data could be routinely shared with healthcare providers (as many requested), to provide more comprehensive understanding of vaccine coverage, and for providers to convey information about transmission risk and vulnerability to patients via tailored communications and messages. As vaccine deferral requires different approaches and solutions than refusal, healthcare providers may benefit from a clearer understanding of the patterns of vaccine uptake in their clinics. Intense efforts were made during the COVID-19 pandemic to improve national immunization information systems and to use these data for action; to better understand vaccine uptake, access, and equity.

Extracting data from childhood vaccination record systems was slower than public health staff would have liked in an outbreak scenario. Longer-term strategies should focus on ensuring all paediatric vaccine providers submit vaccine records to NYSIIS in a timely manner. Such measures may help to strengthen immunization record-keeping, support regional outbreak responses, and rapidly share intelligence during linked VPD outbreaks.

Healthcare providers in this study argued that NYS school vaccination requirements should not permit serologic evidence of antibodies as proof of immunity to certain VPD (in place of vaccination) [14]. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices permits proof of immunity via serologic evidence in place of vaccination in certain instances (e.g., measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella disease), but not for polio [13]. Public health agencies and healthcare providers should, however, assertively explain to parents that infection as a way to circumvent vaccinations is not preferable due to the short- and long-term risks of disease exposure (including death) [43].

Precedents exist for reviewing vaccine legislation due to VPD outbreaks, as occurred in Rockland County in 2019, when religious exemptions for immunizations required for school attendance were removed. Mandatory vaccination, however, does not help with equitable access to vaccination and accurate information, and is not in itself a pathway to promoting vaccine confidence. As social scientists have argued, if ‘mandatory measures are required, the policy should be undergirded by a commitment to building trust in immunisation and understanding of immunisation as a social good’ [44]. Hence, vaccine engagement strategies are a priority to improve local-level coverage and to address concerns around childhood vaccinations in the populations that are most vulnerable to VPD outbreaks.

This qualitative assessment of the poliovirus outbreak and immediate response in Rockland County raises implications for how public health agencies collaborate amid transnational outbreaks. The simultaneous detections of genetically linked polioviruses in the US, UK, and Israel offer an opportunity to evaluate response strategies across countries. Lessons learned from countries who have responded to polio outbreaks in networked communities might help develop transnational solutions to shared challenges.

Limitations

This study was conducted to rapidly inform decision-making as the poliovirus response unfolded, and hence, the study has three main limitations. First, interviews were not conducted with Haredi parents, in particular mothers, which is required to better understand their processes of vaccine decision-making. Second, the study period was limited, making it difficult to rapidly engage residents without taking appropriate sensitization steps through key religious and community leaders, which led to fewer numbers of participants than if more time had been allowed to fully familiarize residents with the study aims. While the study involved nine Community Partners and Organizations (ranging from Jewish doulas and EMT to rabbinic authorities), access to participants working in schools and playgroups would offer more precise knowledge about how vaccine entry requirements are managed in community settings. Lastly, these data represent perceptions shared during the acute phase of the outbreak, shortly after the case-patient was identified, and could have changed throughout the course of the response. Suggested next steps could explore the entire timeline of the response to better understand household expectations of vaccine communication strategies and their perceptions of accessible services how effective longer-term vaccine engagement strategies might be.

Conclusion

This study reviewed immediate responses to a poliovirus outbreak in NYS, which was linked to wastewater detections of genetically linked poliovirus in the UK and Israel. Sustained investment in vaccine engagement and immunization systems strengthening is strongly recommended for public health services to proactively address low vaccination coverage and public doubt in vaccine safety and efficacy and improve understanding of the importance of routine immunization schedules in preventing the re-emergence of vaccine preventable diseases.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all participants for sharing their time as part of this study, Rafael Harpaz, Christopher Duggar, Emily Lutterloh, Jeanne Santoli, Achal Bhatt, Kathleen Dooling, Joanna Gaines, Cara Burns, Carol Brosgart, Peter Dunne, Andrew Charlesworth, and Blima Marcus.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268823001127.

click here to view supplementary material

Data availability statement

The authors do not have permission from study participants to share the data presented in this paper.

Author contribution

Ben Kasstan, Sandra Mounier-Jack, and Tracey Chantler are affiliated to the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Vaccines and Immunisation (NIHR200929) at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in partnership with UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR HPRU, UKHSA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Rockland County Department of Health (RCDOH), or New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH). The CDC had no role in the design, conduct, or analysis of the study. The authors have no financial relationships with any pharmaceutical organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. B.K., S.M-J., and J.R. planned the study; B.K. collected data and conducted analysis; and all authors contributed to writing and editing.

Financial support

Research expenses were funded by the University of Bristol. Researcher travel, accommodation, and subsistence costs were funded by the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC project ID: 0900f3eb81f99107; CDC Project accession number NCIRD-PPLB-8/1/22-99107.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Ethical standard

Ethical approval to conduct this study was provided by the University of Bristol on 10 August 2022, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (NCIRD-PPLB-8/1/22–99107).

References

- [1].Link-Gelles R, Lutterloh E, Schnabel Ruppert P, Backenson PB, St. George K, Rosenberg ES, Anderson BJ, Fuschino M, Popowich M, Punjabi C, Souto M, McKay K, Rulli S, Insaf T, Hill D, Kumar J, Gelman I, Jorba J, Ng TFF, Gerloff N, Masters NB, Lopez A, Dooling K, Stokley S, Kidd S, Oberste MS, Routh J, 2022 U.S. Poliovirus Response Team, 2022 U.S. Poliovirus Response Team, Belgasmi H, Brister B, Bullows JE, Burns CC, Castro CJ, Cory J, Dybdahl-Sissoko N, Emery BD, English R, Frolov AD, Getachew H, Henderson E, Hess A, Mason K, Mercante JW, Miles SJ, Liu H, Marine RL, Momin N, Pang H, Perry D, Rogers SL, Short B, Sun H, Tobolowsky F, Yee E, Hughes S, Omoregie E, Rosen JB, Zucker JR, Alazawi M, Bauer U, Godinez A, Hanson B, Heslin E, McDonald J, Mita-Mendoza NK, Meldrum M, Neigel D, Suitor R, Larsen DA, Egan C, Faraci N, Feumba GS, Gray T, Lamson D, Laplante J, McDonough K, Migliore N, Moghe A, Ogbamikael S, Plitnick J, Ramani R, Rickerman L, Rist E, Schoultz L, Shudt M, Krauchuk J, Medina E, Lawler J, Boss H, Barca E, Ghazali D, Goyal T, Marinelli SJP, Roberts JA, Russo GB, Thakur KT and Yang VQ (2022) Public health response to a case of paralytic poliomyelitis in an unvaccinated person, and detection of poliovirus in wastewater – New York, June–August 2022. The Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 71, 1065–1068. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/pdfs/mm7133e2-H.pdf (accessed 21 October 2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].World Health Organization (2022) Detection of circulating vaccine derived polio virus 2 (cvdpv2) in environmental samples - The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of America. Geneva: World Health Organization, 14 Sep. Available at https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON408 (accessed 21 October 2022).

- [3].World Health Organization (2022) Statement of the thirty-third polio IHR emergency committee. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1 Nov. Available at https://www.who.int/news/item/01-11-2022-statement-of-the-thirty-third-polio-ihr-emergency-committee (accessed 9 November 2022).

- [4].Pan American Health Organization (2022) Epidemiological update: Detection of poliovirus in wastewater: Considerations for the region of the Americas. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization. 30 Dec. Epidemiological Update - Detection of poliovirus in wastewater. Available at https://www.paho.org/en/documents/epidemiological-update-detection-poliovirus-wastewater (accessed 29 January 2023).

- [5].Hill M, Bandyopadhyay S and Pollard AJ (2022) Emergence of vaccine-derived poliovirus in high-income settings in the absence of oral polio vaccine use. Lancet 400, 713–715. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01582-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022) Vaccine-derived poliovirus. 20 Sep. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/polio/hcp/vaccine-derived-poliovirus-faq.html (accessed 22 March 2023).

- [7].New York State Department of Health (2022) Polio vaccination rates by county. Albany: New York State Department of Health, 1 Aug. Available at https://health.ny.gov/diseases/communicable/polio/county_vaccination_rates.htm (accessed 28 August 2022).

- [8].Barskey AE, Schulte C, Rosen JB, Handschur EF, Rausch-Phung E, Doll MK, Cummings KP, Alleyne EO, High P, Lawler J, Apostolou A, Blog D, Zimmerman CM, Montana B, Harpaz R, Hickman CJ, Rota PA, Rota JS, Bellini WJ and Gallagher KM (2012) Mumps outbreak in orthodox Jewish communities in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine 367, 1704–1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].McDonald R, Ruppert PS, Souto M, Johns DE, McKay K, Bessette N, McNulty LX, Crawford JE, Bryant P, Mosquera MC, Frontin S, Deluna-Evans T, Regenye DE, Zaremski EF, Landis VJ, Sullivan B, Rumpf BE, Doherty J, Sen K, Adler E, DiFedele L, Ostrowski S, Compton C, Rausch-Phung E, Gelman I, Montana B, Blog D, Hutton BJ and Zucker HA (2019) Notes from the field: Measles outbreaks from imported cases in orthodox Jewish communities — New York and New Jersey, 2018–2019. The Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report 68, 444–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Patel M, Lee AD, Clemmons NS, Redd SB, Poser S, Blog D, Zucker JR, Leung J, Link-Gelles R, Pham H, Arciuolo RJ, Rausch-Phung E, Bankamp B, Rota PA, Weinbaum CM and Gastañaduy PA (2019) National update on measles cases and outbreaks - United States, January 1 - October 1, 2019. The Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 68, 893–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Office of the Governor of the State of New York (2022) No.21: Declaring a disaster in the State of New York. Albany: Office of the Governor of the State of New York, 9 Sep. Available at https://www.governor.ny.gov/executive-order/no-21-declaring-disaster-state-new-york (accessed 9 September 2022).

- [12].US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016) About VFC, 18 Feb. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/index.html (accessed 21 June 2023).

- [13].Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (2022) Vaccine recommendations and guidelines of the ACIP, 12 July. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/general-recs/special-situations.html (accessed 29 Jan 2023).

- [14].New York State Department of Health (n.d.) 2022–23 School Year: New York State Immunization Requirements for School Entrance/Attendance. Albany: New York State Department of Health. Available at https://www.health.ny.gov/publications/2370.pdf (accessed 2 November 2022).

- [15].New York State Department of Health (2022) Polio vaccination rate by ZIP code: Rockland County. Albany: New York State Department of Health, 1 Aug. Available at https://health.ny.gov/diseases/communicable/polio/zip_code_rates/docs/Rockland_polio_vaccination_report.pdf (accessed 1 November 2022).

- [16].New York State (n.d.) Overview. Albany: New York State. Available at https://www.ny.gov/counties/rockland (accessed 1 November 2022).

- [17].Letley L, Rew V, Ahmed R, Habersaat KB, Paterson P, Chantler T, Saavedra-Campos M and Butler R (2018) Tailoring immunisation programmes: Using behavioural insights to identify barriers and enablers to childhood immunisations in a Jewish community in London, UK. Vaccine 36, 4687–4692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Stein-Zamir C and Israeli A (2019) Timeliness and completeness of routine childhood vaccinations in young children residing in a district with recurrent vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks, Jerusalem, Israel. Eurosurveillance 24(6), 1800004. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.1800004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kasstan B (2022) A free people, controlled only by god”: Circulating and converting criticism of vaccination in Jerusalem. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry 46, 277–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Stadler N (2009) Yeshiva Fundamentalism: Piety, Gender and Resistance in the Ultra-Orthodox World. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kasstan B (2019) Making Bodies Kosher: The Politics of Reproduction among Haredi Jews in England. Oxford: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Taragin-Zeller L (2021) A rabbi of one’s own? Navigating religious authority and ethical freedom in everyday Judaism. American Anthropologist 123, 833–845. 10.1111/aman.13603 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kahn SM (2006) Making technology familiar: Orthodox Jews and infertility support, advice, and inspiration. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry 30, 467–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Birenbaum-Carmeli D (2008) Your faith or mine: A pregnancy spacing intervention in an ultra-orthodox Jewish community in Israel. Reproductive Health Matters 16, 185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ryerson AB, Lang D, Alazawi MA, Neyra M, Hill DT, St. George K, Fuschino M, Lutterloh E, Backenson B, Rulli S, Ruppert PS, Lawler J, McGraw N, Knecht A, Gelman I, Zucker JR, Omoregie E, Kidd S, Sugerman DE, Jorba J, Gerloff N, Ng TFF, Lopez A, Masters NB, Leung J, Burns CC, Routh J, Bialek SR, Oberste MS, Rosenberg ES, 2022 U.S. Poliovirus Response Team, 2022 U.S. Poliovirus Response Team, Anderson BJ, Anderson N, Augustine JA, Baldwin M, Barrett K, Bauer U, Beck A, Belgasmi H, Bennett LJ, Bhatt A, Blog D, Boss H, Brenner IR, Brister B, Brown TW, Buchman T, Bullows J, Connelly K, Cassano B, Castro CJ, Cirillo C, Cone GE, Cory J, Dasin A, de Coteau A, DeSimone A, Chauvin F, Dixey C, Dooling K, Doss S, Duggar C, Dunham CN, Easton D, Egan C, Emery BD, English R, Faraci N, Fast H, Feumba GS, Fischer N, Flores S, Frolov AD, Getachew H, Gianetti B, Godinez A, Gray T, Gregg W, Gulotta C, Hamid S, Hammette T, Harpaz R, Smith LH, Hanson B, Henderson E, Heslin E, Hess A, Hoefer D, Hoffman J, Hoyt L, Hughes S, Hutcheson AR, Insaf T, Ionta C, Miles SJ, Kambhampati A, Kappus-Kron HR, Keys GN, Kharfen M, Kim G, Knox J, Kovacs S, Krauchuk J, Krow-Lucal ER, Lamson D, Laplante J, Larsen DA, Link-Gelles R, Liu H, Lueken J, Ma K, Marine RL, Mason KA, McDonald J, McDonough K, McKay K, McLanahan E, Medina E, Meek H, Mustafa GM, Meldrum M, Mello E, Mercante JW, Mhatre M, Miller S, Migliore N, Mita-Mendoza NK, Moghe A, Momin N, Morales T, Moran EJ, Nabakooza G, Neigel D, Ogbamikael S, O’Mara J, Ostrowski S, Patel M, Paul P, Paziraei A, Peacock G, Pearson L, Plitnick J, Pointer A, Popowich M, Punjabi C, Ramani R, Raymond SJ, Rickerman L, Rist E, Robertson AC, Rogers SL, Rosen JB, Sanders C, Santoli J, Sayyad L, Schoultz L, Shudt M, Smith J, Smith TL, Souto M, Staine A, Stokley S, Sun H, Terranella AJ, Tippins A, Tobolowsky F, Wallace M, Wassilak S, Wolfe A and Yee E (2022) Wastewater testing and detection of poliovirus type 2 genetically linked to virus isolated from a paralytic polio case – New York, March 9–October 11, 2022. The Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 71, 1418–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zuckerman NS, Bar-Or I, Sofer D, Bucris E, Morad H, Shulman LM, Levi N, Weiss L, Aguvaev I, Cohen Z, Kestin K, Vasserman R, Elul M, Fratty IS, Geva M, Wax M, Erster O, Yishai R, Hecht-Sagie L, Alroy-Preis S, Mendelson E and Weil M (2022) Emergence of genetically linked vaccine-originated poliovirus type 2 in the absence of oral polio vaccine, Jerusalem, April to July 2022. EuroSurveillance 27, 2200694. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.37.2200694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Klapsa D, Wilton T, Zealand A, Bujaki E, Saxentoff E, Troman C, Shaw AG, Tedcastle A, Majumdar M, Mate R, Akello JO, Huseynov S, Zeb A, Zambon M, Bell A, Hagan J, Wade MJ, Ramsay M, Grassly NC, Saliba V and Martin J (2022) Sustained detection of type 2 poliovirus in London sewage between February and July, 2022, by enhanced environmental surveillance. Lancet 400, 1531–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Center for Disease Control and Prevention (n.d.) Epidemiologic assistance (epi-aids). Atlanta: Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/eis/request-services/epiaids.html (accessed 1 November 2022).

- [29].Green J. (2005) Qualitative methods. In Green J and Browne J (eds), Principles of Social Research. Maidenhead: Open University Press, pp. 43–92. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cantor JD (2019) Mandatory measles vaccination in New York City – Reflections on a bold experiment. The New England Journal of Medicine 381, 101–103. 10.1056/NEJMp1905941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pink A and Feldman A (2019) We read the guide fueling ultra-Orthodox fears of pig blood in measles vaccines. Forward, 11 April. Available at https://forward.com/news/422354/hasidic-measles-outbreak-peach-handbook/ (accessed 10 February 2023).

- [32].Rockland County (2022) County health department offers additional polio immunization clinics around Rockland, 15 Aug. Available at https://rocklandgov.com/departments/health/press-releases/2022-press-releases/county-health-department-offers-additional-polio-immunization-cl/ (accessed 21 June 2023).

- [33].The New York State Senate (2023) Section 2168: Statewide immunization information system. Available at https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/PBH/2168 (accessed 29 January 2023.

- [34].Closser S (2010) Chasing Polio in Pakistan: Why the World’s Largest Public Health Initiative May Fail. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Renne E (2010) The Politics of Polio in Northern Nigeria. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- [36].United Kingdom Health Security Agency (2022) All children aged 1–9 in London to be offered a dose of polio vaccine. London: United Kingdom Health Security Agency, 10 Aug. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/news/all-children-aged-1-to-9-in-london-to-be-offered-a-dose-of-polio-vaccine (accessed 10 August 2022).

- [37].World Health Organization (2022) Circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 3 – Israel. Geneva: World Health Organization, 15 Apr. Available at https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON366 (accessed 27 June 2022).

- [38].UNICEF (2004) Building trust in immunization: Partnering with religious leaders and groups. New York: UNICEF. Available at ttps://ipc.unicef.org/node/45 (accessed 22 March 2023).

- [39].Jewish Orthodox Women’s Medical Association (JOWMA) (n.d.) Polio: What you need to know. New York City: Jewish Orthodox Women’s Medical Association. Available at https://jowma.org/health-education/polio/ (accessed 29 August 2022).

- [40].Marcus B (2020) A nursing approach to the largest measles outbreak in recent U.S. history: Lessons learned battling homegrown vaccine hesitancy. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 10.3912/OJIN.Vol25No01Man03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kasstan B, Mounier-Jack S, Gaskell KM, Eggo RM, Marks M and Chantler T (2022) We’ve all got the virus inside us now”: Disaggregating public health relations and responsibilities for health protection in pandemic London. Social Science & Medicine 309, 115237. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kasstan B, Mounier-Jack S, Letley L, Gaskell KM, Roberts CH, Stone NRH, Lal S, Eggo RM, Marks M and Chantler T (2022) Localising vaccination services: Qualitative insights on public health and minority group collaborations to co-deliver coronavirus vaccines. Vaccine 40, 2226–2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].León TM, Dorabawila V, Nelson L, Lutterloh E, Bauer UE, Backenson B, Bassett MT, Henry H, Bregman B, Midgley CM, Myers JF, Plumb ID, Reese HE, Zhao R, Briggs-Hagen M, Hoefer D, Watt JP, Silk BJ, Jain S and Rosenberg ES (2022) COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations by COVID-19 vaccination status and previous COVID-19 diagnosis – California and New York, May-November 2021. The Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 71, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Chantler T, Karafillakis E and Wilson J (2019) Vaccination: Is there a place for penalties for non-compliance? Applied Health Economics & Health Policy 17, 265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268823001127.

click here to view supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission from study participants to share the data presented in this paper.