Abstract

Sera obtained from two groups of adult volunteers infected with Norwalk virus (NV) and two groups of patients involved in two natural outbreaks were tested for NV-reactive immunoglobulin M (IgM) by use of a monoclonal antibody, recombinant-antigen-based IgM capture enzyme immunoassay (EIA). No NV-reactive IgM was detected in the preinoculation sera of 15 volunteers, and 14 of 15 showed NV-reactive antibodies postinfection with NV. All of the volunteers showed IgG seroconversion to NV. In the outbreak studies, all 9 persons in one outbreak and 19 of 24 in another outbreak had NV-reactive IgM. In the first outbreak, only three of nine seroconverted to NV, which was likely due to late collection of acute-phase sera. In the second outbreak, 21 of 24 showed IgG seroconversion to NV. Sequencing of viruses isolated from five stool samples selected from those in the second outbreak showed that they were human calicivirus (HuCV) genogroup 1 viruses related, but not identical, to NV. In the volunteer studies, NV-reactive IgM was first detected 8 days postinoculation. The time of development of NV-reactive IgM antibodies in natural outbreaks was estimated to be similar to that found in the volunteer studies. Sera from three Hawaii virus-infected volunteers, four Snow Mountain virus patients, and 80 healthy individuals were negative for NV-reactive IgM, indicating test specificity for HuCV genogroup I infections. This capture IgM EIA is suitable for diagnosis of NV and other HuCV genogroup I infections and is especially useful when sera and fecal samples have not been collected early in the course of an outbreak.

Human caliciviruses (HuCVs) are a major cause of viral gastroenteritis during adolescence and adulthood (3). Viruses in both Norwalk virus (NV) genogroup I (GI) and Snow Mountain virus (SMV) GII are currently circulating (1, 4, 6, 20, 21, 24, 29, 30, 32). Because HuCVs have not been isolated in cell culture, diagnosis is done by PCR, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antigen detection, electron microscopy, or serologic methods. In the past, immunoreagents for detection were obtained from human volunteer sera (14, 18). With the development of a recombinant NV (rNV) capsid antigen (19, 22), NV antigen was made available for use in antibody detection and preparation. Rabbit and guinea pig polyclonal antibodies have been prepared against rNV (10, 22), and mouse monoclonal antibodies against NV for detection of NV in stools have been described (16, 17). Serologic tests once dependent on antigen in stools of volunteers (2, 14) now use rNV (10, 12, 13, 22, 27).

Immunoglobulin G (IgG)-based serologic methods for NV require appropriately timed, paired, acute- and convalescent-phase serum (9), whereas a single serum may be used for IgM-based methods. In one volunteer study, 2 of 20 volunteers had low prechallenge levels of IgM antibodies (5). Another study used an antibody capture method in which all volunteer and also natural outbreak sera were IgM negative up to 3 days after the onset of illness. Seven of 66 were IgM positive within 1 week after symptoms occurred. The test detected 17 of 18 infections in volunteers but only 43 of 72 naturally occurring NV infections from sera collected 2 to 5 weeks after the onset of illness (7).

By use of rNV, one study detected 14 of 14 infected volunteers in a direct binding IgM assay after removal of IgG and IgA (11). IgM was detected in some volunteers as early as 9 days after inoculation, but other volunteers were negative as late as 11 days after inoculation. In another study (31), an IgM antibody capture test detected IgM in 15 of 15 volunteers.

There are no reports of the use of rNV in an antigen capture ELISA in both volunteer and natural infections or of the use of NV monoclonal antibodies in an IgM assay. Whether IgM may, at times, be present in prechallenge sera and the time required for IgM to be detected after infection are still unclear; thus, the diagnostic utility of IgM for NV infection has not been established. The purpose of this study was to determine the diagnostic efficacy of a recombinant antigen, monoclonal-antibody-based ELISA for NV-reactive IgM. Our results serve as a model for detection of infections with other HuCVs. NV was used because it is the prototype HuCV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Serum samples.

Two groups of human volunteers were studied. Both groups consisted of individuals who became ill and either had fourfold increases in titers of IgG antibody against rNV or shed the virus in stool. The first group (group I) consisted of nine individuals (2) from whom sera were collected preinoculation and then 5 days to 22 weeks postinoculation with the 8FIIa strain of NV. One volunteer was challenged with 8FIIa NV on two occasions 4 years apart. The second group (group II) of five volunteers was inoculated with 8FIIa NV in 1995 (26a), and sera were obtained preinoculation and at 4, 5, 8, 14, and 21 days postchallenge. Sera from volunteers challenged with Hawaii virus and sera from a natural SMV outbreak (15) were also tested.

Specimens from two natural gastroenteritis outbreaks that were originally diagnosed as NV by human reagent-based ELISA or radioimmunoassay antigen and antibody tests were also examined. The first outbreak (group I) was clam associated and occurred in Hawaii in 1983 (1a). The second outbreak (groups IIa and IIb) of gastroenteritis occurred in Erie County, N.Y., in 1986 (8). Two distinct components of the second outbreak were involved, which occurred approximately 2 weeks apart. The first one, group IIa, involved persons who had eaten at a particular restaurant. The other, group IIb, involved persons attending a graduation party.

Normal human sera were obtained from a group of adult donors at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center hospital blood bank and from children admitted to the hospital for reasons other than gastroenteritis. All sera were stored at ≤−20°C.

IgM capture antibody ELISA.

Polyvinyl microtiter plates (Dynatech Laboratories, Inc., Chantilly, Va.) were coated with unlabeled rabbit anti-human IgM (Fc5μ) (Accurate Chemical, Westbury, N.Y.) at 0.25 μg/50 μl of 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) per well. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 2 h, washed three times (PBS plus 0.15% Tween 20), and blocked overnight at 20 to 22°C with 5.0% bovine serum albumin and 0.25% Bloom 60 gelatin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) in PBS. The plates were washed three times, and duplicate twofold serial dilutions of human serum, starting at a 1:25 dilution, were made in 50% fetal bovine serum (FBS)–50% 0.025 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.2) with 0.015% Tween 20 (50 μl per well) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The plates were washed five times, and 50 ng of rNV in 50 μl of the Tris-HCl-FBS buffer described above was added to each well of one of the duplicate rows. To the second row, 50 μl of Tris-HCl-FBS buffer without rNV was added.

After overnight incubation at 20 to 22°C, the plates were washed five times and a combination of two previously described murine monoclonal antibodies, 1C9 and 1D8 (1:5000 dilution of ascitic fluid), directed against NV (17) was added, in Tris-HCl-FBS buffer, to all wells and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. We used both antibodies because we previously found that doing so increased the sensitivity of the NV detection assay (17). The plates were washed, and peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (heavy and light chains; Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc., Gaithersburg, Md.) at 1 μg/ml in Tris-HCl-FBS buffer plus 1% normal rabbit serum was added and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The plates were washed five times. Substrate for peroxidase (0.05 ml of o-phenylenediamine–H2O2, Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, Ill.) was added and left for up to 10 min, and the reaction was stopped with 0.1 ml of 1 N H2SO4. The A492 of the solution was measured in a plate reader spectrophotometer (Whittaker Bioproducts, Walkersville, Md.).

The endpoint titer was defined as the highest dilution of serum giving an A492 that was ≥0.200 above the A492 of the corresponding no-antigen well. This endpoint was determined by using a value of ≥3 times the standard deviation of the A492 obtained with 10 prechallenge sera tested at a 1:25 dilution in no-antigen wells. To confirm IgM specificity, IgG and IgA were removed from the group I volunteer sera with Quik-Sep IgM (Isolab Inc., Akron, Ohio) and tested in the same manner as the whole serum.

IgG antibody ELISA.

Alternate rows in polyvinyl microtiter plates were coated with rNV at 50 ng/50 μl of 0.1 M PBS per well. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 4 h and washed three times, and all wells were blocked overnight as in the IgM antibody capture test. The plates were washed three times, and twofold serial dilutions of human serum, starting at a 1:800 dilution, were made in Tris-HCl-FBS buffer (50 μl per well) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Sera with titers of <1:800 were retested at a 1:100 dilution. Dilutions for each serum were made in both the rNV-coated row and the control row. The plates were washed four times, and peroxidase-labeled goat anti-human IgG (heavy and light chains; Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Inc.) at 1 μg/ml in Tris-HCl-FBS buffer was added and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Substrate for peroxidase was added as described for the IgM antibody capture test, and the A492 of the solution was measured in a plate reader spectrophotometer. The IgG titer was defined as the highest dilution of serum giving an A492 that was ≥0.200 higher than that of the corresponding no-antigen well, based on criteria described for the IgM value. Sera with acute-phase titers of ≥1:25,600 were repeat tested.

RT-PCR and sequencing of viruses in stool samples.

Stool samples from six patients in the group II outbreak were analyzed by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR for HuCVs. Viral nucleic acid was purified from stool as previously described (21). Twenty-microliter aliquots of extracted RNA were amplified by RT-PCR by using two sets of primers: p110-SR48/50/52 (small, round-structured virus [SRSV] GI specific) and p110-NI (SRSV GII specific) followed by slot blot hybridization with probes specific for HuCV (23). Samples with virus-specific amplicons were cloned into TA cloning vector pCRII and transformed into Escherichia coli One Shot cells in accordance with the manufacturer’s (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.) instructions. Plasmid DNA from positive clones was purified with Qiagen Maxi columns (Qiagen, Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.). Cloned DNA was sequenced by the Nucleic Acids Core Laboratory, Baylor College of Medicine. Sequence information was analyzed by using the facilities of the Molecular Biology Computational Resource, Information Technology Program and The Department of Cell Biology, Baylor College of Medicine.

RESULTS

A summary of the results of the studies detailed in Tables 2 to 6 is given in Table 1. No group I or II volunteers demonstrated detectable IgM in their prechallenge sera (Tables 2 and 3). In group I (Table 2), NV-specific IgM antibodies were detected in all but one volunteer after virus inoculation. Volunteer 3a, 3b, who was challenged on two occasions (4 years apart), showed no significant difference in serologic response to the two challenges. All of these volunteers demonstrated IgG seroconversion to NV. In group II (Table 3), all volunteers were IgM negative for up to 5 days after infection and all became IgM positive by 8 days and were still positive by 21 days postinoculation (Table 3). In an IgG ELISA to rNV, all of the volunteers in groups I and II showed fourfold or greater rises in IgG titer (Tables 2 and 3). Removal of IgG and IgA (by use of Quik-Sep IgM) in sera from subjects in volunteer group I did not change the outcome of the test for IgM (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Detection of IgG and IgM responses to NVa in volunteer group I by rNV ELISA

| Volunteer no. | Time post- inoculation | Reciprocal of serum dilution

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| IgG | IgM | ||

| 1 | Preb | 12,800 | <25 |

| 5 days | 6,400 | <25 | |

| 6 wk | 102,400 | 800 | |

| 2 | Pre | 102,400 | <25 |

| 9 days | 204,800 | 6,400 | |

| 3 wk | 409,600 | 6,400 | |

| 3a | Pre | 204,800 | <25 |

| 6 wk | 819,200 | 1,600 | |

| 14 wk | 204,800 | 800 | |

| 3b | Pre | 51,200 | <25 |

| 3 wk | 102,400 | 3,200 | |

| 6 wk | 409,600 | 1,600 | |

| 4 | Pre | 3,200 | <25 |

| 3 wk | 25,600 | 800 | |

| 5 | Pre | 3,200 | <25 |

| 5 days | 6,400 | <25 | |

| 22 wk | 25,600 | <25 | |

| 6 | Pre | 1,600 | <25 |

| 4 wk | 204,800 | 6,400 | |

| 7 wk | 204,800 | 1,600 | |

| 7 | Pre | 12,800 | <25 |

| 3 wk | 819,200 | 800 | |

| 7 wk | 409,600 | 100 | |

| 8 | Pre | 1,600 | <25 |

| 7 wk | 51,200 | 3,200 | |

| 18 wk | 25,600 | 3,200 | |

| 9 | Pre | 6,400 | <25 |

| 5 days | 6,400 | <25 | |

| 6 wk | 102,400 | 3,200 | |

Samples were from volunteers in studies done in 1970 to 1976. Volunteer 3a in 1972 was rechallenged in 1976 (volunteer 3b).

Pre, preinoculation.

TABLE 6.

Prevalence of NV-specific IgG and IgM in normal sera as determined by rNV ELISA

| Age range (yr) | No. of subjects | Reciprocal of serum dilution

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG

|

IgM

|

||||

| <100 | ≥100 | <25 | ≥25 | ||

| 1–4 | 20 | 15 | 5 | 20 | 0 |

| 5–17 | 20 | 7 | 13 | 20 | 0 |

| 18–29 | 20 | 3 | 17 | 20 | 0 |

| 30–59 | 20 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 0 |

TABLE 1.

Summary of detection studies for NV-specific IgM and for IgG seroconversions in normal sera, NV volunteers, and natural outbreaks of NV gastroenteritisa

| Group | IgM+ | IgG scb+ | IgM+ IgG sc− | IgG sc+ IgM− |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal sera (n = 80) | 0 | NAc | NA | NA |

| Volunteers | ||||

| I (n = 10) | 9 | 10 | 0 | 1 |

| II (n = 5) | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Outbreaks | ||||

| I (n = 9)d | 9 | 3 | 6 | 0 |

| IIa (n = 16)e | 15 | 13 | 3 | 1 |

| IIb (n = 8) | 4 | 8 | 0 | 4 |

sc, seroconversion.

NA, not applicable.

Acute-phase sera were collected late (see Table 4).

Viruses from selected stools were shown to be GI viruses. Those in group IIa were most closely related to virus MDV1, and those in group IIb were most closely related to virus V Wal/90/UK (see Results).

TABLE 3.

Detection of volunteer group II IgG and IgM responses to NVa by rNV ELISA

| Volunteer no. | Time post- inoculation | Reciprocal of serum dilution

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| IgG | IgM | ||

| 1 | Preb | 51,200 | <25 |

| 4 days | 25,600 | <25 | |

| 5 days | 25,600 | <25 | |

| 8 days | 12,800 | 1,600 | |

| 2 wk | 102,400 | 12,800 | |

| 3 wk | 204,800 | 1,600 | |

| 2 | Pre | 3,200 | <25 |

| 4 days | 3,200 | <25 | |

| 5 days | 3,200 | <25 | |

| 8 days | 204,800 | 1,600 | |

| 2 wk | 204,800 | 3,200 | |

| 3 wk | 409,600 | 3,200 | |

| 3 | Pre | 1,600 | <25 |

| 4 days | 800 | <25 | |

| 5 days | 1,600 | <25 | |

| 8 days | 25,600 | 3,200 | |

| 2 wk | 51,200 | 3,200 | |

| 3 wk | 102,400 | 800 | |

| 4 | Pre | 3,200 | <25 |

| 4 days | 6,400 | <25 | |

| 5 days | 6,400 | <25 | |

| 8 days | 12,800 | 400 | |

| 2 wk | 409,600 | 3,200 | |

| 3 wk | 409,600 | 1,600 | |

| 5 | Pre | 1,600 | <25 |

| 4 days | 800 | <25 | |

| 5 days | 3,200 | <25 | |

| 8 days | 6,400 | 25 | |

| 2 wk | 51,200 | 400 | |

| 3 wk | 102,400 | 800 | |

Samples were from volunteers in a study done during 1995.

Pre, preinoculation.

Acute-phase sera from the patients in outbreak group I were collected 5 to 8 days after the onset of illness. Convalescent-phase sera were collected 3 to 6 weeks postillness. All nine patients in outbreak group I had high IgM antibody titers in both acute- and convalescent-phase sera (Table 4). Four patients showed fourfold rises in IgM levels. All nine patients had high titers of IgG antibody to rNV, and three had fourfold or greater rises in IgG antibody titer. Two patients had rises in both IgG and IgM antibody titers (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Detection of IgG and IgM responses to NVa in outbreak group I by rNV ELISA

| Patient no. | Time postonset of illness | Reciprocal of serum dilution

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| IgG | IgM | ||

| 1 | 7 days | 51,200 | 800 |

| 3 wk | 102,400 | 3,200 | |

| 2 | 7 days | 409,600 | 1,600 |

| 3 wk | 409,600 | 800 | |

| 3 | 8 days | 51,200 | 6,400 |

| 3 wk | 204,800 | 25,600 | |

| 4 | 7 days | 51,200 | 3,200 |

| 3 wk | 102,400 | 25,600 | |

| 5 | 6 days | 25,600 | 1,600 |

| 4 wk | 3,276,800 | 6,400 | |

| 6 | 5 days | 819,200 | 3,200 |

| 5 wk | 819,200 | 3,200 | |

| 7 | 7 days | 51,200 | 6,400 |

| 6 wk | 51,200 | 6,400 | |

| 8 | 7 days | 51,200 | 12,800 |

| 6 wk | 51,200 | 6,400 | |

| 9 | 6 days | 25,600 | 3,200 |

| 3 wk | 3,276,800 | 3,200 | |

Outbreak group II components a and b consisted of 24 patients, 16 in component a and 8 in component b, which occurred approximately 2 weeks later (Table 5). From patients in group IIa, acute-phase sera were obtained between 5 and 8 days postexposure and convalescent-phase sera were obtained 3 weeks postexposure. From patients in group IIb, acute-phase sera were obtained 4 days after a point source exposure and convalescent-phase sera were obtained 2 weeks postexposure. Six patients, all of whom were in group IIa, had IgM in their acute-phase sera. A total of 19 had NV-specific IgM in their convalescent-phase sera.

TABLE 5.

Detection of IgG and IgM responses to NVa in outbreak group II by rNV ELISA

| Group and patient no. | Time post- exposure | Reciprocal of serum dilution

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| IgG | IgM | ||

| IIa | |||

| 1b | 5–8 days | 25,600 | <25 |

| 3 wk | 204,800 | 3,200 | |

| 2 | 5–8 days | 12,800 | 800 |

| 3 wk | 204,000 | 800 | |

| 3 | 5–8 days | 12,800 | <25 |

| 3 wk | 204,800 | 6,400 | |

| 4b | 5–8 days | 51,200 | 6,400 |

| 3 wk | 409,600 | 6,400 | |

| 5 | 5–8 days | 6,400 | 25 |

| 3 wk | 51,200 | 800 | |

| 6 | 5–8 days | 12,800 | <25 |

| 3 wk | 25,600 | 25 | |

| 7 | 5–8 days | 6,400 | <25 |

| 3 wk | 51,200 | <25 | |

| 8 | 5–8 days | 102,400 | 3,200 |

| 3 wk | 409,600 | 6,400 | |

| 9b | 5–8 days | 25,600 | 800 |

| 3 wk | 409,600 | 3,200 | |

| 10 | 5–8 days | 25,600 | <25 |

| 3 wk | 409,600 | 3,200 | |

| 11 | 5–8 days | 12,800 | <25 |

| 3 wk | 102,400 | 25 | |

| 12 | 5–8 days | 25,600 | <25 |

| 3 wk | 51,200 | 800 | |

| 13 | 5–8 days | 1,600 | <25 |

| 3 wk | 102,400 | 3,200 | |

| 14 | 5–8 days | 51,200 | 3,200 |

| 3 wk | 1,638,400 | 3,200 | |

| 15 | 5–8 days | 6,400 | <25 |

| 3 wk | 102,400 | 25 | |

| 16 | 5–8 days | 25,600 | <25 |

| 3 wk | 51,200 | 25 | |

| IIb | |||

| 1 | 4 days | 12,800 | <25 |

| 2 wk | 204,800 | 800 | |

| 2 | 4 days | 12,800 | <25 |

| 2 wk | 51,200 | <25 | |

| 3 | 4 days | 6,400 | <25 |

| 2 wk | 51,200 | 400 | |

| 4 | 4 days | 6,400 | <25 |

| 2 wk | 25,600 | 50 | |

| 5b | 4 days | 6,400 | <25 |

| 2 wk | 51,200 | 800 | |

| 6b | 4 days | 25,600 | <25 |

| 2 wk | 102,400 | <25 | |

| 7 | 4 days | 3,200 | <25 |

| 2 wk | 51,200 | <25 | |

| 8 | 4 days | 12,800 | <25 |

| 2 wk | 51,200 | <25 | |

Samples were from patients involved in two outbreaks of gastroenteritis in Erie County, N.Y., in 1986 that were reported to be due to NV (8). Sera were collected at the noted intervals postexposure to the virus, in contrast to those in Tables 2 and 3.

The virus in this patient’s stool sample was analyzed for genogroup (see Fig. 1).

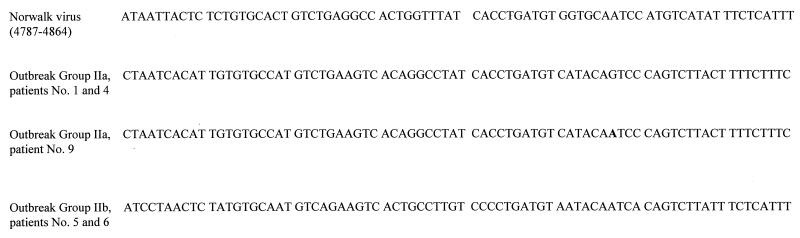

Stool samples from six patients involved in the group IIa and -b outbreak were positive by RT-PCR and by hybridization to HuCV genogroup 1-specific primers and probes. Five positive samples were cloned and sequenced. All of the sequences obtained were related, but not identical, to that of NV (Fig. 1). The viral sequences from outbreak group IIa stools (those from patients 1, 4, and 9 in Table 5) were very similar to each other, with that from patient 9 differing from those from patients 1 and 4 by one nucleotide. The portions sequenced had 94 to 96% nucleotide sequence identity with an SRSV, V Ward 1/90, from the United Kingdom (28) (accession no. Z29479) and 70 to 72% nucleotide sequence identity with NV (Fig. 1). The viral sequences from outbreak group IIb stools (patients 5 and 6 in Table 5) were identical. The portions sequenced had 98% nucleotide identity with a Maryland calicivirus, MDV1 (25) (accession no. U07612) and 77% nucleotide identity with NV (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequences of viruses from selected stool samples from patients in outbreak group II (Table 5). The 119-bp RT-PCR product was cloned and sequenced as described in the text. A 78-bp unique sequence was obtained.

Three serum pairs from volunteers challenged with Hawaii virus and four serum pairs obtained from patients involved in an SMV outbreak were tested for NV-specific IgM. Both acute- and convalescent-phase samples of all seven serum pairs were NV IgM negative. However, they did cross-react in the rNV IgG assay (data not shown). Eighty sera from normal individuals ranging from 1 to 59 years of age were also tested. Eighty-five percent of the adults aged 18 to 29 were positive for NV-specific IgG antibodies, and all of those aged 30 and over were positive. None of the sera from normal persons were IgM positive at a 1:25 dilution (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

Previous reports have been inconclusive about whether IgM antibodies to NV are present in the preinoculation sera of volunteers in human challenge studies. Two studies showed that all preinoculation sera were IgM antibody negative (7, 11), whereas another study found that 40% of preinoculation sera were NV IgM positive at a serum dilution of 1:20 and 21% were positive at a 1:40 serum dilution (31). An additional study found that 10% of preinoculation sera were positive for IgM antibodies to NV (5). In the two volunteer groups that we examined, no NV-reactive IgM was detected in preinoculation sera at a dilution of 1:25. This included both preinoculation serum samples collected from one volunteer who was challenged on two occasions 4 years apart. Furthermore, of the 80 sera from blood donors and asymptomatic children tested, none had detectable IgM antibody to NV at a 1:25 dilution. Based on our studies, it appears that NV-reactive IgM is present only after recent exposure to NV or NV-like viruses and that the test is specific for HuCV GI viruses. One explanation for the two reported studies that showed IgM in preinoculation sera is that different assay methods were used. Our method is the first to use both rNV antigen and anti-NV monoclonal antibodies to detect NV-reactive IgM in an IgM capture format.

The time when IgM antibodies to NV can first be detected is important in identifying outbreaks. In one volunteer study, 2 of 14 volunteers seroconverted as early as 9 days after inoculation with 8FIIa NV. Six other volunteers were negative 11 days after inoculation. However, all eventually became positive (11). No sera were collected from our volunteers in group I between 5 and 9 days postinoculation. The one volunteer from whom we collected serum at 9 days postinoculation was IgM positive. In group II, all five volunteers were negative at 5 days postinoculation and all were IgM antibody positive by day 8. Sera were not available from days 6 and 7. It has been shown that on rechallenge, previously ill volunteers produced IgM antibody to NV (5). We confirmed this finding by using the rNV IgM antibody capture format on sera from the one volunteer in group I who had been challenged twice. The time for development of NV-reactive IgM in the two outbreak groups was similar to that found in our volunteers and to that found in another outbreak study (7).

All patients in outbreak group I were positive for NV-reactive IgM. There was NV-reactive IgM in 15 of 16 patients in group IIa and in 4 of 8 in group IIb. The difference between the rates of detection may be due to the two different viruses that were involved, as shown by viral sequencing. Sequence analysis showed that neither of the viruses involved was identical to NV but that both were closer to other described GI viruses, which was not apparent when the outbreak was originally described in 1986 (8). Thus, the developed IgM method was able to detect different GI strains of viruses and was not limited to detection of antibody to the 8FIIa strain.

The IgM antibody capture test we used did not react with paired sera from volunteers infected with Hawaii virus, sera from patients infected with SMV (both viruses are classified as GII), or normal human sera, showing the specificity of this test for HuCV GI viruses. However, sera obtained from these Hawaii virus volunteers and SMV patients did show increases in the titer of IgG antibody to rNV. A solid-phase immune electron microscopy study also found that IgM antibodies appeared to be more virus strain specific than IgG antibodies (26).

Our NV IgM antibody capture enzyme immunoassay is suitable for use in the detection of recent NV and other HuCV GI infections and should be especially useful when appropriate acute- and convalescent-phase paired sera are not available or when fecal samples are not collected during the period of detectable virus shedding. NV is the prototype HuCV, and the results obtained with this virus and the NV-related viruses we tested serve as models for other HuCVs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Deanne Rhodes, Frances Tseng, and Susan Pusek for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by NIH grants AI 38036 (M.K.E.) and T32 AI 07471 (K.J.S.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ando T, Monroe S S, Gentsch J R, Jin Q, Lewis D C, Glass R I. Detection and differentiation of antigenically distinct small round-structured viruses (Norwalk-like viruses) by reverse transcription-PCR and Southern hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:64–71. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.64-71.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1a.Blacklow, N. R. Unpublished data.

- 2.Blacklow N R, Cukor G, Bedigian M K, Echeverria P, Greenberg H B, Schreiber D S, Trier J S. Immune response and prevalence of antibody to Norwalk enteritis virus as determined by radioimmunoassay. J Clin Microbiol. 1979;10:903–909. doi: 10.1128/jcm.10.6.903-909.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blacklow N R, Greenberg H B. Viral gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med. 1990;325:252–264. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107253250406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cubitt W D, Jiang X, Wang J, Estes M K. Sequence similarity of human caliciviruses and small round structured viruses. J Med Virol. 1994;43:252–258. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890430311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cukor G, Nowak N A, Blacklow N R. Immunoglobulin M responses to the Norwalk virus of gastroenteritis. Infect Immun. 1982;37:463–468. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.2.463-468.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dimitrov D H, Dashti S A H, Ball J M, Bishbishi E, Alsaeid K, Jiang X, Estes M K. Prevalence of antibodies to human caliciviruses (HuCVs) in Kuwait established by ELISA using baculovirus-expressed capsid antigens representing two genogroups of HuCVs. J Med Virol. 1997;51:115–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erdman D D, Gary G W, Anderson L J. Development and evaluation of an IgM capture enzyme immunoassay for diagnosis of recent Norwalk virus infection. J Virol Methods. 1989;24:57–66. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(89)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleissner M L, Herrmann J E, Booth J W, Blacklow N R, Nowak N A. Role of Norwalk virus in two foodborne outbreaks of gastroenteritis: definitive virus association. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:165–172. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gary G W, Anderson L J, Keswick B H, Johnson P C, DuPont H L, Stine S E, Bartlett A V. Norwalk virus antigen and antibody response in an adult volunteer study. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:2001–2003. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.10.2001-2003.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graham D Y, Jiang X, Tanaka T, Opekum A R, Madore H P, Estes M K. Norwalk virus infection of volunteers: new insights based on improved assays. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:34–43. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray J J, Cunliffe C, Ball J, Graham D Y, Desselberger U, Estes M K. Detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM), IgA, and IgG Norwalk virus-specific antibodies by indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with baculovirus-expressed Norwalk virus capsid antigen in adult volunteers challenged with Norwalk virus. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:3059–3063. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.3059-3063.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray J J, Jiang X, Morgan-Capner P, Desselberger U, Estes M K. Prevalence of antibodies to Norwalk virus in England: detection by enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay using baculovirus-expressed Norwalk virus capsid antigen. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1022–1025. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.4.1022-1025.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green K Y, Lew J F, Jiang X, Kapikian A Z, Estes M K. Comparison of the reactivities of baculovirus-expressed recombinant Norwalk virus capsid antigen with those of the native Norwalk virus antigen in serologic assays and some epidemiologic observations. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2185–2191. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2185-2191.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenberg H B, Wyatt R G, Valdesuso J, Kalica A R, London W I, Chanock R M, Kapikian A F. Solid phase microtiter radioimmunoassay for detection of the Norwalk strain of acute nonbacterial epidemic gastroenteritis virus and its antibodies. J Med Virol. 1978;17:127–133. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890020204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guest C, Spitalny K C, Madore H P, Pray K, Dolin R, Herrmann J E, Blacklow N R. Foodborne Snow Mountain agent gastroenteritis in a school cafeteria. Pediatrics. 1987;79:559–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardy M E, Tanaka T N, Kiyamoto N, White L J, Ball J M, Jiang X, Estes M K. Antigenic mapping of the recombinant Norwalk virus capsid protein using monoclonal antibodies. Virology. 1996;217:252–261. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrmann J E, Blacklow N R, Matsui S M, Lewis T L, Estes M K, Ball J M, Brinker J P. Monoclonal antibodies for detection of Norwalk virus antigen in stools. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2511–2513. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2511-2513.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrmann J E, Nowak N A, Blacklow N R. Detection of Norwalk virus in stools by enzyme immunoassay. J Med Virol. 1985;17:127–133. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890170205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang X, Graham D Y, Wang K, Estes M K. Norwalk virus genome cloning and characterizations. Science. 1990;250:1580–1583. doi: 10.1126/science.2177224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang X, Matson D O, Velazquez F R, Calva J J, Zhong W M, Hu J, Ruiz-Palacios G M, Pickering L K. Study of Norwalk-related viruses in Mexican children. J Med Virol. 1995;47:309–316. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890470404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang X, Wang J, Estes M K. Characterization of SRSVs using RT-PCR and a new antigen ELISA. Arch Virol. 1995;140:363–374. doi: 10.1007/BF01309870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang X, Wang M, Graham D Y, Estes M K. Expression, self-assembly, and antigenicity of the Norwalk virus capsid protein. J Virol. 1992;66:6527–6532. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6527-6532.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LeGuyader F, Estes M K, Neill F H, Green J, Brown D W G, Atmar R L. Evaluation of a degenerate primer for the PCR detection of human caliciviruses. Arch Virol. 1996;141:2225–2235. doi: 10.1007/BF01718228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LeGuyader F, Neill F H, Estes M K, Monroe S S, Ando T, Atmar R L. Detection and analysis of a small round-structured virus strain in oysters implicated in an outbreak of acute gastroenteritis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4268–4272. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4268-4272.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lew J F, Kapikian A Z, Valdesuso J, Green K Y. Molecular characterization of Hawaii virus and other Norwalk-like viruses: evidence for genetic polymorphism among human caliciviruses. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:535–542. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.3.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis D C, Lightfoot N F, Pether J V S. Solid-phase immune electron microscopy with human immunoglobulin M for serotyping of Norwalk-like viruses. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:938–942. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.5.938-942.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26a.Moe, C. L. Unpublished data.

- 27.Monroe S S, Stine S E, Jiang X, Estes M K, Glass R I. Detection of antibody to recombinant Norwalk virus antigen in specimens from outbreaks of gastroenteritis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2866–2872. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.2866-2872.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norcott J P, Green J, Lewis D, Estes M K, Barlow K L, Brown D W. Genomic diversity of small round structured viruses in the United Kingdom. J Med Virol. 1994;50:207–213. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890440312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parker S P, Cubitt W D, Jiang X. Enzyme immunoassay using baculovirus-expressed human calicivirus (Mexico) for the measurement of IgG responses and determining its seroprevalence in London, UK. J Med Virol. 1995;46:194–200. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890460305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smit T K, Steele A D, Penze I, Jiang X, Estes M K. Study of Norwalk virus and Mexico virus infections at Ga-Rankuwa hospital, Ga-Rankuwa, South Africa. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2381–2385. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2381-2385.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Treanor J J, Jiang X, Madore H P, Estes M K. Subclass-specific serum antibody responses to recombinant Norwalk virus capsid antigen (rNV) in adults infected with Norwalk, Snow Mountain, or Hawaii virus. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1630–1634. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.6.1630-1634.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamazaki K, Oseto M, Seto Y, Utagawa E, Kimoto T, Minekawa Y, Inouye S, Yamazaki S, Okuno Y, Oishi I. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction detection and sequence analysis of small round-structured viruses in Japan. Arch Virol. 1996;12:271–276. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6553-9_29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]