Abstract

The poor fluorescence properties of magneto-fluorescent paramagnetic-ion (Gd, Mn, or Co) doped I-III-VI quantum dots (QDs) at higher paramagnetic-ion doping concentrations have limited their use in magnetic-driven water-based applications. This work presents, for the first time, the use of stable magneto-fluorescent Gd-doped AgInS2 QDs at high Gd mole ratios of 16, 20, and 30 for the fluorescence detection and adsorption of Ag+ ions in water environments. The effect of pH, initial concentration, contact time, and adsorbent dosage were systematically evaluated. The AgInS2 QDs with the least Gd mole ratio (16) exhibited the best fluorescence characteristics (LOD = 0.88, R2 = 0.9549) while all materials showed good adsorption properties under optimized conditions (pH of 2, initial concentration of 30 ppm, contact time of 10 min and adsorbent dosage of 0.02 g) and a pseudo 2nd order reaction was followed. The adsorption mechanism was proposed to be a combination of ion-exchange, electrostatic interaction, complexation, and diffusion processes. Application in environmental wastewater samples revealed complete removal of Ag + ions alongside Ti2+ Pb2+, Ni2+, Cr3+, and Zn2+ ions.

Keywords: Magneto-fluorescent, Quantum dots, Sensing, Adsorption

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The increased cases of environmental pollution have led to stricter regulations for water quality assessments in industrial effluents. Water quality assessments commonly involve the concentration evaluations of heavy metals such as Pb, Hg, Cd, As, Cu, Cr, Ni, Fe, and Zn [1,2]. Other heavy metals like Ag, Au, Mo, and Co are less popularly studied but they still require removal since they can be toxic at elevated concentrations. Ag remains one of the least studied heavy metals in wastewater yet it is toxic for many biological systems [3]. Moreover, the emergence of Ag-containing products in industries (i.e. anti-bacterial products, textiles, and electronics) and medicine (i.e. medical devices, anti-cancer treatments) has increased the occurrence of Ag in the environment [3,4]. Therefore, rapid Ag+ ion detection and removal approaches at wide concentration ranges are crucial.

The quest for applying safe and sustainable magneto-fluorescent materials for various applications other than the ever-exploited biological use has been a subject of current research interest. As a result, the ternary I-III-VI quantum dots (QDs) are currently being evaluated as fluorescent components of magneto-fluorescent materials for water quality monitoring and remediation studies [5,6]. Besides their safety compared to conventional binary II-VI QDs [[7], [8], [9]], the presence of the paramagnetic ions (Gd, Mn, Ni, or Co) and magnetic materials (Fe3O4) within their current structure enables them for potential use for easy separation from aqueous solutions via magnetic field attractions [10]. Ternary I-III-VI quantum dots have demonstrated promising potential in the fluorescence detection of various heavy metals [11,12] but rarely in the detection of Ag [13]. Furthermore, a few challenges such as low magnetic loading capacity due to loss in fluorescence at high magnetic loading and stability at certain pHs are eminent [14,15], limiting their use for water remediation. Over the years, a few authors explored the development of magneto-fluorescent Fe3O4@I-III-VI QD nanocomposites for fluorescence detection of heavy metals in water [5,6]. For example, Kurshanov et al. fabricated a magneto-fluorescent microsphere based on CaCO3–Fe3O4–AgInS2/ZnS for the detection of Co2+, Ni2+, and Pb2+ ions in water. The microsphere was prepared by doping CaCO3 microspheres with Fe3O4 NPs, followed by capping with various layers of polymer and depositing the TGA-capped AgInS2/ZnS QDs [5]. In another development, Liu et al. fabricated oligonucleotide-capped CuInS2@Fe3O4 nanocomposite by conjugating Fe3O4 NPs with oligonucleotide-capped CuInS2 QDs for fluorescence detection of arsenate in water [6]. Although both nanocomposites displayed magnetic functions which could offer high adsorption capacities and easy separation for the removal of heavy metals, adsorption studies were not reported. Moreover, the preparation of the nanocomposites involved several steps for the synthesis and conjugation of the multiple components. Recently, we reported a one-pot synthesis of stable magneto-fluorescent citrate-capped Gd-doped AgInS2 QDs at high Gd loading (up to 20 Gd mol ratio) with enhanced photoluminescence characteristics [16]. In this work, citrate-capped Gd-doped AgInS2 (AIS) QDs were synthesized up to a Gd mole ratio of 30. For the first time, we present paramagnetic ion–doped I-III-VI QDs-Gd-doped AgInS2 QDs for the fluorescence detection and removal of Ag + ions in aqueous solutions. To describe the potential for real life application, the adsorption isotherms, kinetics and interferences of other heavy metals present in industrial wastewater samples were discussed.

2. Material and methods

All chemicals (Sigma-Aldrich, South Africa) were used as purchased. Deionized water was used for all aqueous preparations.

2.1. Synthesis of the quantum dots

Gd-doped AIS QDs were prepared following our previous report [16]. Typically, 0.0453 g of Gd2O3 (0.1248 mmol) was dissolved in 300 μL HCl under mild heat and made up to 10 mL with deionized water. The Gd2O3 solution was added to a AgNO3/InCl3/sodium citrate/thioglycolic acid (TGA) mixture (15 mL) in another beaker at pH 6 in the presence of Na2S followed by refluxing at 95 °C under stirring. The materials were centrifuged (5000 rpm), washed with ethanol, and dried at 80 °C for 1 h.

2.2. Detection and adsorption studies

Ag+ ion solutions were diluted using deionized water and the pH was adjusted using dilute hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide. 0.02 g of adsorbent material and 30 mL of Ag+ ion solutions were added to glass vials and shaken for 10 min at 200 rpm. This was followed by fluorescence analysis at an excitation wavelength of 375 nm at room temperature. The limit of detection (LOD) was calculated according to the literature [17]. The fluorescence intensity of Gd-AIS QDs PL peak was measured 5 times in the presence and absence of Ag+ at various concentrations and the standard deviations were achieved. The slope was obtained from the plot of fluorescence intensity vs Ag+ concentration. Thus, the LOD was estimated using equation (1).

| (1) |

where σ is the standard deviation of the response of the Gd-AIS QDs fluorescence intensity and S is the slope of the plot of Gd-AIS QDs fluorescence intensity in the absence and presence at Ag + at various concentrations (calibration curve).

The adsorbent was collected with a magnet. The Ag+ solutions were analyzed using an Agilent 5900 ICP-OES before and after adsorption. The % removal and amount of heavy metal ions adsorbed (Qe) were calculated by equations (2), (3) respectively.

| (2) |

| (3) |

where Qe is the amount of heavy metal ion adsorbed at equilibrium (mg/g), Co and Ce are the initial and equilibrium concentrations of heavy metal ions solutions (mg/L), V is the volume of solution (L) and m is the mass of the adsorbent (g).

Acidified water samples (Ag-WS) were collected during a Ag recovery process from an industrial company. The acidified water samples were adjusted to pH 2 using dilute nitric acid.

The adsorption studies were subjected to isotherm models such as Langmuir and Freudlich as well as kinetic models such as pseudo-1st and pseudo-2nd orders to investigate the adsorption mechanism.

2.2.1. Langmuir model: adsorption at homogenous sites

| (4) |

Where Ce is the concentration of the metal ion at the equilibrium (mg/L), Qe is the amount of metal ion adsorbed per mass of the nanocomposite (adsorbent) (mg/g), K is the equilibrium constant and QM is the amount of metal ion required to form a monolayer.

The plot of Ce/Qe versus Ce typically gives a straight line whose slope = (1/QM) and intercept = (1/K) (1/QM).

2.2.2. Freundlich model: adsorption at heterogeneous sites

| (5) |

Where n is an empirical constant. A plot of log Qe versus log Ce gives a straight line with a slope = 1/n and an intercept = log K.

2.2.3. The pseudo-first-order kinetics

| (6) |

Where Qt is the amount of heavy metals adsorbed at a time (t).

2.2.4. The pseudo-second-order kinetics

| (7) |

2.3. Characterization

The spectrofluorophotometer (RF-6000, Shimadzu, Japan) was utilized for the fluorescence analysis. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra were measured using a PerkinElmer Spectrum Two UATR-FTIR spectrometer. The morphology of the samples was analyzed using a JEOL electron microscope (JEM-2100) at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. Surface zeta potential measurements were carried out using a Malvern Zetasizer Nano at 25 °C. An Agilent 5900 inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) and Spectro Xepos05 energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (ED-XRF) instruments were used to determine the Gd, Ag, In, and S concentrations of the as-synthesized materials.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Synthesis of Gd-AIS QDs and fluorescence detection

The Gd-doped AgInS2 QDs were synthesized with a 7:16 TGA: sodium citrate mole ratio suggesting that the surface functionality is dominated by carboxylate groups from citrate molecules and a few from the TGA molecules hence the materials are referred to as “citrate-capped Gd-doped AgInS2 QDs”. At such high Gd loading the carboxylate groups on the AIS QD surface coordinate with Gd3+ ions and passivates the surfaces, filling the defect sites and thus the stable fluorescence properties [16]. The elemental analysis (Table 1) of the Gd-AIS QDs showed an obvious increase in the Gd concentration at increased Gd mole ratios while the slight decreases in Ag and In were attributed to possible cation-exchange occurring during the Gd doping when Gd diffuses into the AgInS2 QDs lattice.

Table 1.

Elemental analysis of the Gd-AIS QDs as increased Gd mole ratios.

| Elements | Gd (%) | Ag (%) | In (%) | S (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gd16-AIS | 29.16 | 0.392 | 1.24 | 2.02 |

| Gd20-AIS | 39.91 | 0.353 | 0.979 | 2.22 |

| Gd30-AIS | 45.87 | 0.359 | 0.938 | 2.00 |

The results of the fluorescence evaluation of all Gd-AIS QDs (Gd mole ratios 16, 20, and 30) after Ag+ ions interactions revealed a slight PL enhancement at low concentrations and gradual PL quenching at higher concentrations (Fig. 1A–G). These behaviors were due to the initial passivation of the surface defects at low concentrations and saturation of surface traps at high concentrations, which destabilized the QDs hence the quenching [18,19]. Moreover, the excess Ag+ interacts with the citrate functionality on the QD surface, which reduces the Ag + to Ag0 (nanoparticles), further destabilizing the QDs.

Fig. 1.

PL spectra and comparative Stern-Volmer's plot of Gd-AIS QDs at Gd mole ratios of 16 (A–C), 20 (D–E), and 30 (F–G) after adsorption of Ag+ ions at increased concentrations (1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 30, 50, 70, 100 ppm). Excitation wavelength: 375 nm.

Also, the exhibited slight blue-shift was associated with Ag+ ion diffusion into the QD lattice as a result of cation-exchange (Fig. 1A–G and Table 2). However, among all materials, Gd-doped AIS QDs with a Gd mole ratio of 16 showed the best limit of detection (LOD) with a correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.9549 (Table 3). The lower LOD obtained with Gd16-AIS QDs compared to Gd20-AIS QDs and Gd30-AIS QDs could be due to their larger number of surface defects due to the lower degree of Gd-citrate passivation present on the QD surface [20] thus appreciating even the smallest concentration of Ag+ ion to passivate existing defects hence the PL enhancement at Ag+ion low concentrations.

Table 2.

Photoluminescence properties of Gd-AIS QDs at varied Gd mole ratios after interaction with Ag+ ions at increased concentrations.

| Gd mole ratio |

16 |

20 |

30 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample name | PL intensity (a. u.) | PL peak (nm) | PL intensity (a. u.) | PL peak (nm) | PL intensity (a. u.) | PL peak (nm) |

| Gd16-AIS QDs | 129.3 | 603 | 89.52 | 579 | 103.6 | 575 |

| Gd-AIS QDs + 1 ppm | 431.8 | 587 | 122.1 | 555 | 280.1 | 579 |

| Gd-AIS QDs + 3 ppm | 494.8 | 587 | 138.2 | 543 | 261 | 579 |

| Gd-AIS QDs + 5 ppm | 557.8 | 587 | 149 | 543 | 239 | 583 |

| Gd-AIS QDs + 7 ppm | 620.8 | 587 | 161.7 | 543 | 218 | 571 |

| Gd-AIS QDs + 10 ppm | 683.8 | 587 | 150 | 543 | 142.2 | 559 |

| Gd-AIS QDs + 30 ppm | 765.1 | 587 | 186.6 | 543 | – | – |

| Gd-AIS QDs + 50 ppm | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Gd-AIS QDs + 70 ppm | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Gd-AIS QDs + 100 ppm | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Table 3.

Comparative Ag + ion detection characteristics of Gd-AIS QDs at Gd mole ratios 16, 20, and 30.

| Material | LOD (ppm) | R2 | Range (ppm) | λ max (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gd16-AIS QDs | 0.88 | 0.9549 | 1–10 | 575 |

| Gd20-AIS QDs | 2.36 | 0.7007 | 1–30 | 547 |

| Gd30-AIS QDs | 1.23 | 0.8351 | 1–30 | 547 |

3.2. Adsorption properties – effects of pH, concentration, contact time, and adsorbent dosage

Generally, lower pH values (2 and 4) produced higher % Ag removals than higher pH (6) for all adsorbents, except for Gd30-AIS QDs which showed a decrease in % removal at pH 2 compared to pH 4 and 6. The superiority of the lower pH on the removal of Ag+ ions over the higher ones can be explained based on the tendency of the carboxylate ions of the citric acid to be protonated at low pHs (pKa1 = 3.13, pKa2 = 4.76, and pKa3 = 6.40), causing loss of some of the carboxylate groups, thus aggregation of the QDs and some part of the surface of the QDs available for the adsorption of Ag+ ions. Comparatively, all Gd-AIS QDs produced almost 100% removal throughout the studied pH range (Fig. 2A). Ag removals above 95% from 1 to 100 ppm were exhibited by Gd16-AIS and Gd20-AIS QDs while Gd30-AIS QDs showed a slight decrease to 90% at 100 ppm (Fig. 2B). The slight decrease might be due to the lower number of carboxylic acid groups available on the Gd-AIS QD surface at a higher Gd mole ratio compared to QDs with a lower Gd mole ratio.

Fig. 2.

Adsorption of Ag + using Gd-AIS (Gd mole ratio 16, 20, and 30) - Effects of pH (2, 4, and 6) (adsorbent dosage = 0.02 g and initial Ag+ ion concentration = 30 ppm, contact time = 10 min) (A), increased initial Ag+ ion concentration (1–100 ppm) (dosage = 0.02 g, contact time = 10 min and pH) (B), contact time (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 30, 45 and 60 min) (pH = 2, adsorbent dosage = 0.02 g and initial Ag+ ion concentration = 30 ppm) (C) and increased adsorbent dosage (0.005, 0.01, 0.02, 0.03 and 0.04 g) (pH = 2, contact time = 10 min and initial Ag+ ion concentration = 30 ppm) (D).

The contact time studies revealed that maximum adsorption of Ag+ ions could be achieved within 1 min for all Gd-AIS QDs (Fig. 2C). % Removal values of 98%, 96% and 94% were exhibited by Gd16-AIS, Gd20-AIS and Gd30-AIS QDs respectively. The rapid uptake of Ag+ ions was attributed to the sufficient number of binding sites on the surface of the QDs.

The study on the effect of adsorbent dosage for Ag+ ions adsorption showed that adsorption of Ag+ ions increased with increased adsorbent dosage from 0.005 g to 0.02 g and was kept constant at higher dosages for all Gd-AIS QDs (Fig. 2D). However, Gd30-AIS QDs showed a significantly lower % removal (63%) at the lowest dosage (0.005 g) compared to Gd16-AIS QDs and Gd20-AIS QDs (92% and 95%). This was also associated with the lower number of carboxylic acid groups available for binding on the QDs at a higher Gd mole ratio.

3.3. Adsorption isotherm and kinetics studies

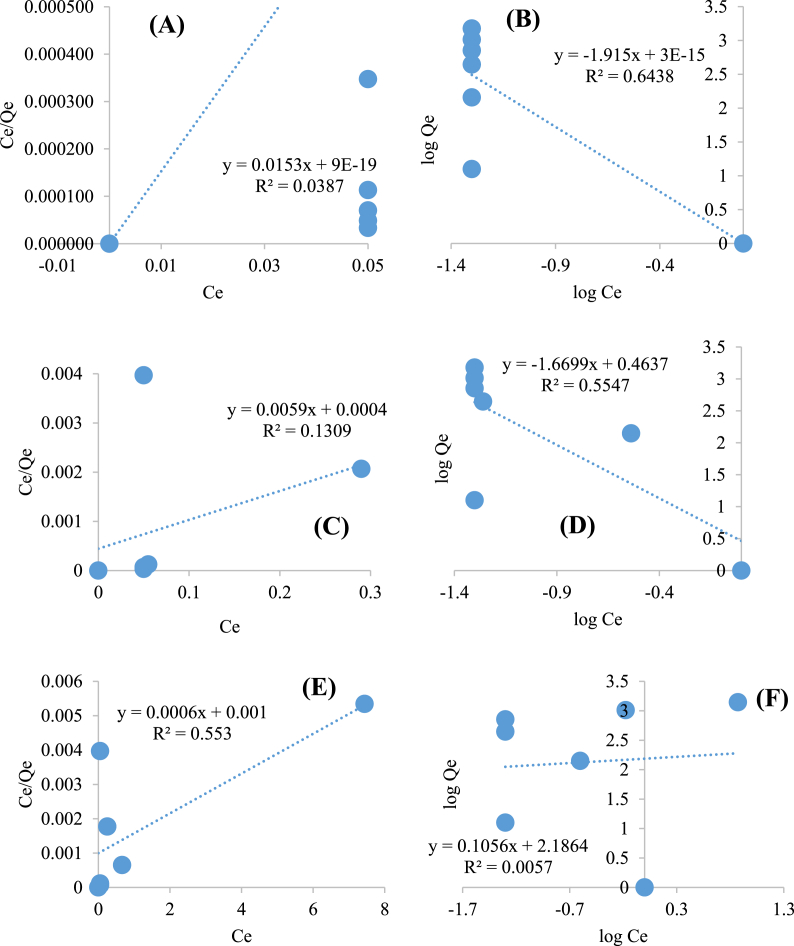

Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models (equations (4), (5))) were applied to study the adsorption characteristics for Ag+ ions removal using the Gd-AIS QDs at increased Gd mole ratios (16, 20, and 30). As seen in Fig. 2B, the adsorbents showed % Ag removal above 95% for the studied Ag+ ion concentration range. Thus, it was not possible to obtain a linear plot of Ce/Qe vs Ce (Langmuir) and log Qe vs log Ce (Freundlich) with good R2 values since the Ce values were constant throughout the concentration range (Fig. 3A–F, Table 4, Table 5). Moreover, the maximum adsorption capacities (QM) obtained experimentally decreased from 1503 mg/g (for Gd16-AIS and Gd20-AIS QDs) to 1392 mg/g (Gd30-AIS QDs) (Table 4), which is much higher than most reported adsorbent materials. The Gd16-AIS QDs not only offer high adsorption capabilities but also offer simultaneous fluorescent detection of Ag+ ions at wider concentration ranges and comparable LOD (Table 3) compared to other materials (Table 6).

Fig. 3.

Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms for Ag + ions adsorption onto Gd16-AIS QDs (A–B), Gd20-AIS QDs (C–D), and Gd30-AIS QDs (E–F).

Table 4.

Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm parameters for adsorption of Ag + ions onto Gd16-AIS QDs, Gd20-AIS QDs, and Gd30-AIS QDs.

| % Ag removal | Co (ppm) | Ce (ppm) | Qe (mg/g) | Ce/Qe | Log Ce | Log Qe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gd16-AIS QDs | ||||||

| 99.89 | 0.89 | 0.05 | 12.6 | 0.003968 | −1.301029996 | 1.100370545 |

| 99.89 | 9.65 | 0.05 | 144 | 0.000347 | −1.301029996 | 2.158362492 |

| 99.89 | 29.55 | 0.05 | 442.5 | 0.000113 | −1.301029996 | 2.645913275 |

| 99.89 | 47.61 | 0.05 | 713.4 | 0.000070 | −1.301029996 | 2.853333105 |

| 99.89 | 68.82 | 0.05 | 1031.55 | 0.000048 | −1.301029996 | 3.013490283 |

| 99.89 | 100.26 | 0.05 | 1503.15 | 0.000033 | −1.301029996 | 3.177002321 |

| Gd20-AIS QDs | ||||||

| 99.89 | 0.89 | 0.05 | 12.6 | 0.003968 | −1.301029996 | 1.100370545 |

| 96.99 | 9.65 | 0.29 | 140.4 | 0.002066 | −0.537602002 | 2.147367108 |

| 99.63 | 29.55 | 0.055 | 442.425 | 0.000124 | −1.259637311 | 2.64583966 |

| 99.89 | 47.61 | 0.05 | 713.4 | 0.000070 | −1.301029996 | 2.853333105 |

| 99.89 | 68.82 | 0.05 | 1031.55 | 0.000048 | −1.301029996 | 3.013490283 |

| 99.89 | 100.26 | 0.05 | 1503.15 | 0.000033 | −1.301029996 | 3.177002321 |

| Gd30-AIS QDs | ||||||

| 99.89 | 0.89 | 0.05 | 12.6 | 0.003968254 | −1.301029996 | 1.100370545 |

| 97.92 | 9.65 | 0.25 | 141 | 0.00177305 | −0.602059991 | 2.149219113 |

| 99.89 | 29.55 | 0.05 | 442.5 | 0.000112994 | −1.301029996 | 2.645913275 |

| 99.89 | 47.61 | 0.05 | 713.4 | 7.00869E-05 | −1.301029996 | 2.853333105 |

| 99.03 | 68.82 | 0.665 | 1022.325 | 0.000650478 | −0.177178355 | 3.009588981 |

| 92.58 | 100.26 | 7.44 | 1392.3 | 0.005343676 | 0.871572936 | 3.143732823 |

Table 5.

Freundlich and Langmuir parameters for Ag + ions adsorption isotherms.

| Langmuir |

Freundlich |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorbent | Qm (mg/g) | KL | R2 | 1/n | KF | R2 |

| Gd16-AIS QDs | 65.36 | 1.7 × 1016 | 0.0387 | 1.915 | 1 | 0.6438 |

| Gd20-AIS QDs | 169.49 | 14.75 | 0.1309 | 1.670 | 2.909 | 0.5547 |

| Gd30-AIS QDs | 1667 | 0.6 | 0.553 | 0.106 | 153.6 | 0.0057 |

Table 6.

Comparative LODs and maximum adsorption capacities for Ag + ions using various materials.

| Material | Detection/removal | Range (mg/L) | LOD (mg/L) | Qm (mg/g)/%removal | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gd16-AgInS2 QDs | Yes/Yes | 1–100 | 0.88 | 1503 mg/g | This work |

| AgInSZn QDs | Yes/No | 30–100 | 28.01 | – | [13] |

| Fluorescent carbon nanosheets | Yes/Yes | 0–20 30–120 |

1.74 16.16 |

98% | [13] |

| Naphthalimide fluorescent probe@MSN | Yes/Yes | 2.16–17.3 | 0.7769 | 14.8 mg/g | [21] |

| DNA-functionalized@MSS@ Au NPs |

Yes/Yes | 0.1079–10.79 | 0.01079 | ~99% | [22] |

| BODIPY-functionalized Fe3O4 | Yes/No | 0.0002–0.002 | 220 | – | [23] |

| Non-functionalized Ferrite | Yes/No | 0.00002–0.0006 | 0.000004 | – | [24] |

| Bithiophene-based COF | Yes/Yes | 0.02589–10.79 | 0.02589 | 398.61 mg/g | [25] |

| Tetraphenylethene-based fluorescent chemosensor | Yes/No | 0–1.4 | 0.2384 | – | [26] |

The adsorption kinetics of the three adsorbents was studied by subjecting the data to pseudo 1st and 2nd order models (equations (6), (7))). The fitted kinetic parameters produced R2 > 0.99 for the pseudo 2nd order model for all the adsorbents (Fig. 4A–F and Table 7). In addition, the experimental adsorption capacity (Qe (Exp.)) was consistent with the calculated adsorption capacity (Qe (Cal.)) (Table 7). This indicated that all adsorbents followed a pseudo 2nd order model for Ag + adsorption, which suggested a chemical adsorption behavior. This might be a result of electrostatic interaction between the Ag+ ions and the carboxylate groups on the adsorbent surfaces.

Fig. 4.

Pseudo 1st and 2nd order model curves for Ag + ion adsorption for Gd16-AIS QDs (A–B), Gd20-AIS QDs (C–D), and Gd30-AIS QDs (E–F).

Table 7.

Pseudo 1st order and 2nd order parameters for Ag + ions adsorption kinetic studies.

| 1st order |

2nd order |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorbent | Qe (Cal) | K1 | R2 | Qe(Cal.) | Qe (Exp.) | K2 | R2 |

| Gd16-AIS QDs | 1.341 | 0.0132 | 0.0527 | 476.19 | 471.98 | 35 | 1 |

| Gd20-AIS QDs | 2.066 | 0.0161 | 0.3188 | 476.19 | 472.2 | 70 | 1 |

| Gd30-AIS QDs | 1.141 | 0.0031 | 0.0876 | 476.19 | 469.12 | 35 | 1 |

3.4. Adsorption mechanism

The FTIR analysis confirmed the interaction of the Ag+ ions with O-Hstr (3600-3400 cm−1) and C=Ostr (1800-1500 cm−1) groups on the QDs (Fig. 5A). There were increases in the intensities of these functional groups, a slight shift to the lower frequency region, and a small broadening of the band after Ag+ ions adsorption. These observations implied feasible electrostatic as well as complexation interactions [27,28]. The PL enhancement of the Gd-AIS QDs after adsorption also supports these observations (i.e., binding of Ag+ ion onto the QDs surface), which demonstrated passivated surface defects (Fig. 1A–G). Additionally, the blue-shifted emission suggested some diffusion of Ag+ ions into the QD lattice (Fig. 1A–G, Table 2). Furthermore, the electrostatic interaction between the Ag+ ions and the adsorbent was supported by the increase in the positive charge on the adsorbent from +4.12 mV to +20 mV at increased Ag + ion concentrations (Table 8).

Fig. 5.

FTIR spectra of Gd16-AIS QDs before and after the adsorption of Ag+ ions (50 ppm) (A), Digital image of Gd16-AIS, Gd20-AIS, Gd30-AIS QDs after Ag+ ions adsorption showing the color change from brown (Gd-AIS QDs) to black (Ag0 nanoparticles formation) at increased Ag + ions concentrations at increased concentrations (1, 10, 30, 50, 70 and 100 ppm, left to right) (B), and TEM images of Gd16-doped AgInS2 QDs before (C) and after (D) the adsorption Ag+ ions (10 ppm), the proposed mechanism for adsorption of Ag+ ions onto the Gd-AIS QDs surface (E).

Table 8.

Zeta potential values of citrate-capped Gd-AIS QDs nanocomposites in the absence and presence of Ag+ ions.

| Zeta potential (mV) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag+ conc. (ppm) | 0 | 10 | 30 | 100 |

| Gd16-AIS@ QDs | +4.16 | +5.83 | +9.02 | +17.6 |

Higher adsorption capabilities were obtained at lower Gd mole ratios, as a result of the higher number of free carboxylate groups on the QDs surfaces [16]. The pseudo 2nd order model fittings suggested that Ag + ions removal was related to chemical adsorption processes. These might include electrostatic interactions between the Ag + ions and the carboxylate groups, followed by the formation of Ag-carboxylate complexes which concurrently could lead to some reduction to Ag nanoparticles formation (Fig. 5B–E). The complexation and reduction reactions were evident from the color change from brown (Gd-AIS QDs) to black (Ag0 nanoparticles formation) at increased Ag+ ions concentrations (Fig. 5B). The nanoparticle formation was further supported by the results from TEM analysis (Fig. 5C and D), where the initial small spherical shaped QDs of particle size 5.8 nm (Fig. 5C) were surrounded by Ag NPs (Fig. 5D) after their interaction with Ag+ ions.

3.5. Industrial wastewater application

The elemental analysis of the real water sample after adsorption showed that both the Ag+ and the trace ions (Ti, Pb, Cr, Ni, and Zn) were significantly removed (Table 9). The interaction of the trace elements with the Gd16-AIS QDs was also seen in the PL spectra (Fig. 6). The PL peak of Gd16-AIS QDs was quenched after the adsorption of Ag+ ions (47.7 ppm) both in the deionized water and in the water sample (Ag-WS). However, the latter showed a slight increase in the intensity coupled with a shift towards the red region compared to the deionized water after the interaction. This showed some effects of the interfering ions in the Ag-WS. The interaction of ternary I-III-VI QDs with trace concentrations of Ti, Pb, Cr, and Zn through carboxylate binding during has been reported [29]. PL enhancement was reported for interactions with low concentrations of Zn, Cr, and Ti while PL quenching was reported with Pb [13,[30], [31], [32], [33], [34]].

Table 9.

Elemental analysis of acidified industrial wastewater before and after adsorption using Gd16-AIS QDs.

| Element | Ag | Ti | Pb | Cr | Ni | Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration before adsorption (ppm) | 47.7 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 3.1 | 2.1 |

| Concentration after adsorption (ppm) | **ND | **ND | **ND | **ND | **ND | **ND |

| %Ag removal | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

*ND = Not detected below 0.01 ppm **ND = Not detected below 0.05 ppm.

Fig. 6.

PL spectra of Gd16-AIS QDs alone, with 47.7 ppm Ag+ ions (deionized water) and real water (RW) sample. The inset shows the enlargement of the lower parts of the spectra.

These findings revealed that the Gd-AIS QDs could be used for the removal of Ag+ ions from industrial wastewater in the presence of trace elements within the respective interference/Ag ratio. Additionally, the material could be used for trace element removal from industrial wastewater. The fluorescence detection of Ag+ ions in the Ag-WS was not favorable in the presence of these interfering ions due to the interactions of the trace elements with the QDs that resulted in different PL responses.

4. Conclusion

This work reports the sensing and adsorption kinetics characteristics of Gd-doped AgInS2 QDs toward detecting and removing Ag + ions from aqueous solutions. Effects of variation of pH, initial concentration, contact time, and adsorbent dosage were effectively evaluated. All three Gd-doped AIS QDs (Gd-16, 20, and 30) displayed high % removals within 1 min and optimum adsorbent dosage of 0.02 g. Efficient adsorption of Ag+ ions was achieved with a pH range of 2–6 and increased Ag+ ion concentration resulted in maintained % removals above 95% for all Gd-AIS QDs. The QDs with the least Gd mole ratio (16) exhibited the best sensing characteristics (LOD = 0.88 ppm) as well as adsorption properties (Q m = 1503 mg/g) and the pseudo 2nd order reaction was well-followed. Although the interaction of the other elements (Ti, Pb, Ni, Cr, and Zn ions) in the industrial wastewaters with the QDs interfered with the fluorescence detection of Ag+ ions, the study showed the potential of the Gd-doped AIS QDs in removing Ag+ ions from industrial wastewaters without any interference from Ti, Pb, Ni, Cr, and Zn ions.

Author contribution statement

Bambesiwe M. May: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Olayemi J. Fakayode: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Mokae F. Bambo; Ajay K Mishra; Edward N Nxumalo: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Bambesiwe M. May reports financial support was provided by National Research Foundation.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Institute for Nanotechnology and Water Sustainability (iNanoWS) of the University of South Africa, South African Department of Science and Innovation (DSI), Mineral Council (Mintek) (South Africa), and South African National Research Foundation (NRF) Professional Development Programme (PDP) Pre-doctoral Fellowship.

References

- 1.Qasem N.A.A., Mohammed R.H., Lawal D.U. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater: a comprehensive and critical review. Npj Clean Water. 2021;4 doi: 10.1038/s41545-021-00127-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azimi A., Azari A., Rezakazemi M., Ansarpour M. Removal of heavy metals from industrial wastewaters: a review. ChemBioEng Rev. 2017;4:37–59. doi: 10.1002/cben.201600010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang H., Rose N. Trace element pollution records in some UK lake sediments, their history, influence factors and regional differences. Environ. Int. 2005;31:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naeemullah T.G., Kazi H.I., Afridi F., Shah S.S., Arain K.D., Brahman J., Ali M.S., Arain Simultaneous determination of silver and other heavy metals in aquatic environment receiving wastewater from industrial area, applying an enrichment method. Arab. J. Chem. 2016;9:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2014.10.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurshanov D.A., Khavlyuk P.D., Baranov M.A., Dubavik A., Rybin A.V., Fedorov A.V., Baranov A.V. Magneto-fluorescent hybrid sensor caco3-fe3o4-agins2/zns for the detection of heavy metal ions in aqueous media. Materials. 2020;13:1–11. doi: 10.3390/ma13194373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Z., Li G., Xia T., Su X. Ultrasensitive fluorescent nanosensor for arsenate assay and removal using oligonucleotide-functionalized CuInS2 quantum dot@magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles composite. Sensor. Actuator. B Chem. 2015;220:1205–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2015.06.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie R., Rutherford M., Peng X., Fayette V. Semiconductor Nanocrystal-Based Nanosensors and Metal Ions Sensing. 2009:5691–5697. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hauck T.S., Anderson R.E., Fischer H.C., Newbigging S., Chan W.C.W. In vivo quantum-dot toxicity assessment. Small. 2010;6:138–144. doi: 10.1002/smll.200900626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolny-Olesiak J., Weller H. Synthesis and application of colloidal CuInS2 semiconductor nanocrystals. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2013;5:12221–12237. doi: 10.1021/am404084d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kothavale V.P., Sharma A., Dhavale R.P., Chavan V.D., Shingte S.R., Selyshchev O., Dongale T.D., Park H.H., Zahn D.R.T., Salvan G., Patil P.B. Carboxyl and thiol-functionalized magnetic nanoadsorbents for efficient and simultaneous removal of Pb(II), Cd(II), and Ni(II) heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions: studies of adsorption, kinetics, and isotherms. J. Phys. Chem. Solid. 2023;172 doi: 10.1016/j.jpcs.2022.111089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.May B.M., Bambo M.F., Hosseini S.S., Sidwaba U., Nxumalo E.N., Mishra A.K. A review on I-III-VI ternary quantum dots for fluorescence detection of heavy metals ions in water: optical properties, synthesis and application. RSC Adv. 2022;12:11216–11232. doi: 10.1039/d1ra08660j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen P.M., Bawendi M.G. Ternary I - III - VI quantum dots luminescent in the red to near-infrared. J. Am. Soc. 2008;130:9240–9241. doi: 10.1021/ja8036349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.May B.M., Fakayode O.J., Mashale K.N., Bambo M.F., Mishra A.K., Nxumalo E.N. Journal of Water Process Engineering Detection and separation of silver ions from industrial wastewaters using fluorescent D -glucose carbon nanosheets and quaternary silver indium zinc sulphide quantum dots. J. Water Process Eng. 2022;49 doi: 10.1016/j.jwpe.2022.102944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ding K., Jing L., Liu C., Hou Y., Gao M. Magnetically engineered Cd-free quantum dots as dual-modality probes for fluorescence/magnetic resonance imaging of tumors. Biomaterials. 2014;35:1608–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng C.Y., Ou K.L., Huang W.T., Chen J.K., Chang J.Y., Yang C.H. Gadolinium-based CuInS2/ZnS nanoprobe for dual-modality magnetic resonance/optical imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2013;5:4389–4400. doi: 10.1021/am401428n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.May B.M., Fakayode O.J., Bambo M.F., Sidwaba U., Nxumalo E.N., Mishra A.K. Stable magneto-fluorescent gadolinium-doped AgInS2 core quantum dots (QDs) with enhanced photoluminescence properties. Mater. Lett. 2021;305 doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2021.130776. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wen J., Lv Y., Xia P., Liu F., Xu Y., Li H., Chen S.S., Sun S. A water-soluble near-infrared fluorescent probe for specific Pd2+ detection. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018;26:931–937. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J.L., Zhu C.Q. Functionalized cadmium sulfide quantum dots as fluorescence probe for silver ion determination. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2005;546:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2005.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahu A., Kang M.S., Kompch A., Notthoff C., Wills A.W., Deng D., Winterer M., Frisbie C.D., Norris D.J. Electronic impurity doping in CdSe nanocrystals. Nano Lett. 2012;12:2587–2594. doi: 10.1021/nl300880g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.May B.M., Fakayode O.J., Bambo M.F., Sidwaba U., Nxumalo E.N., Mishra A.K. Stable magneto-fluorescent gadolinium-doped AgInS 2 core quantum dots (QDs) with enhanced photoluminescence properties. Mater. Lett. 2021;305:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2021.130776. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu H., Jia J., Xu Y., Qian X., Zhu W. A reusable bifunctional fluorescent sensor for the detection and removal of silver ions in aqueous solutions. Sensor. Actuator. B Chem. 2018;265:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2018.01.241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu M., Wang Z., Zong S., Chen H., Zhu D., Wu L., Hu G., Cui Y. SERS detection and removal of mercury(II)/Silver(I) using oligonucleotide-functionalized core/shell magnetic silica sphere@Au nanoparticles. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014;6:7371–7379. doi: 10.1021/am5006282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kursunlu A.N., Ozmen M., Guler E. Novel magnetite nanoparticle based on BODIPY as fluorescent hybrid material for Ag(I) detection in aqueous medium. Talanta. 2016;153:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2016.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.López-García I., Muñoz-Sandoval M.J., Hernández-Córdoba M. Use of a simple magnetic material for the determination and speciation of very low amounts of silver and gold. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2023;202 doi: 10.1016/j.sab.2023.106643. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y., Wang Q., Li Y., Hu R. Bithiophene-based COFs for silver ions detection and removal. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022;346 doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2022.112289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jagadhane K.S., Bhosale S.R., Gunjal D.B., Nille O.S., Kolekar G.B., Kolekar S.S., Dongale T.D., Anbhule P.V. Tetraphenylethene-based fluorescent chemosensor with mechanochromic and aggregation-induced emission (AIE) properties for the selective and sensitive detection of Hg2+and Ag+Ions in aqueous media: application to environmental analysis. ACS Omega. 2022;7:34888–34900. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c03437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.A.F.G.F. NATHAN YEE LIANE G. BENNING, VERNON R. PHOENIX Characterization of metal-cyanobacteria sorption reactions: a combined macroscopic and infrared spectroscopic investigation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004;38:775–782. doi: 10.1063/1.1136478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kyzas G.Z., Siafaka P.I., Lambropoulou D.A., Lazaridis N.K., Bikiaris D.N. Poly(itaconic acid)-grafted chitosan adsorbents with different cross-linking for Pb(II) and Cd(II) uptake. Langmuir. 2014;30:120–131. doi: 10.1021/la402778x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.May B.M., Bambo M.F., Hosseini S., Nxumalo E.N., Mishra A.K. A review on I – III – VI ternary quantum dots for fl uorescence detection of heavy metals ions in water : optical properties , synthesis and application. RSC Adv. 2022;12:11216–11232. doi: 10.1039/d1ra08660j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parani S., Oluwafemi O.S. Selective and sensitive fluorescent nanoprobe based on AgInS2-ZnS quantum dots for the rapid detection of Cr (III) ions in the midst of interfering ions. Nanotechnology. 2020;31 doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/ab9c58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y., Wang Q., Zha T., Min J., Gao J., Zhou C., Li J., Zhao M., Li S. Green and facile synthesis of high-quality water-soluble Ag-In-S/ZnS core/shell quantum dots with obvious bandgap and sub-bandgap excitations. J. Alloys Compd. 2018;753:364–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.04.242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pons T., Pic E., Lequeux N., Cassette E., Bezdetnaya L., Guillemin F., Marchal F., Dubertret B. Cadmium-free CuInS2/ZnS quantum dots for sentinel lymph node imaging with reduced toxicity. ACS Nano. 2010;4:2531–2538. doi: 10.1021/nn901421v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo W., chen N., Tu Y., Dong C., Zhang B., Hu C., Chang J. Synthesis of Zn-Cu-In-S/ZnS Core/Shell quantum dots with inhibited blue-shift photoluminescence and applications for tumor targeted bioimaging. Theranostics. 2013;3:99–108. doi: 10.7150/thno.5361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu M., Luan W., Tu S.T., Mleczko L. Green synthesis of CuInS2/ZnS nanocrystals with high photoluminescence and stability. J. Nanomater. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/842365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.