Abstract

Objective

Conservative pain management strategies for knee osteoarthritis (KOA) have limited effectiveness and do not employ a pain-mechanism informed approach. Pain Informed Movement is a novel intervention combining mind-body techniques with neuromuscular exercise and pain neuroscience education (PNE), aimed at improving endogenous pain modulation. While the feasibility and acceptability of this program has been previously established, it now requires further evaluation in comparison to standard KOA care.

Design

This protocol describes the design of a pilot two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) with an embedded qualitative component. The primary outcome is complete follow-up rate. With an allocation ratio of 1:1, 66 participants (33/arm) (age ≥40 years, KOA diagnosis or meeting KOA NICE criteria, and pain intensity ≥3/10), will be randomly allocated to two groups that will both receive 8 weeks of twice weekly in-person exercise sessions. Those randomized to Pain Informed Movement will receive PNE and mind-body technique instruction provided initially as videos and integrated into exercise sessions. The control arm will receive neuromuscular exercise and standard OA education. Assessment will include clinical questionnaires, physical and psychophysical tests, and blood draws at baseline and program completion. Secondary outcomes are program acceptability, burden, rate of recruitment, compliance and adherence, and adverse events. Participants will be invited to an online focus group at program completion.

Conclusion

The results of this pilot RCT will serve as the basis for a larger multi-site RCT aimed at determining the program's effectiveness with the primary outcome of assessing the mediating effects of descending modulation on changes in pain.

Keywords: Randomized controlled trial, Pilot, Knee osteoarthritis, Pain informed movement, Endogenous pain modulation

1. Introduction

With an increasing global prevalence of knee OA (KOA) and no highly effective treatments for pain, there is an urgent need to improve conservative pain management strategies to avoid the associated negative outcomes such as limited mobility and multimorbidity [1]. Current clinical practice guidelines strongly recommend exercise and patient education as the core conservative management strategies [2,3]. Various types of exercises are recommended including neuromuscular exercises which are focused on improving knee functionality [4]. However, these treatments are only moderately effective for controlling pain [5], which therefore begs for a deeper understanding of the mechanisms of KOA pain and filling the corresponding gaps with mechanism-based treatment strategies.

Current recommended methods for conservative management are not predicated on pain mechanisms, while evidence for neural sensitization and dysregulation of intrinsic pain modulation is widely reported [6]. Mind-body approaches have the potential to fill these gaps in the management of KOA through a combination of physical postures, breathing techniques, meditation, mindfulness, and relaxation [7]. The effects are reported to be mechanistically related to the regulation of nociceptive signals [8]. For instance, breathing exercises can lead to the disruption of the association of pain and sympathetic nervous system activation [9], leading to modulation of autonomic functions [10]. Meditation and relaxation can create a state of calm and provide a sensation of being in a place of safety (a parasympathetic state) [11], which can lead to changes in one's pain experience [12]. Mindfulness and mindful movements can improve where and how to focus, develop skills to control the response to pain [13], and influence the pain experience through emotional regulation and interoception [8].

A management strategy that can be a valuable addition to exercise, Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE) is a technique that shifts the focus from the diseased knee joint and the assumption that pain stems from degenerative structural changes [14]. Unlike standard OA education that has historically had a biomedical influence [14], PNE reconceptualizes pain as a danger signal and introduces intrinsic modulation of pain to influence the pain experience. Omitting biomedical language from KOA education can lead to significantly lower perceptions that physical activity is injurious to the knee joint, lower fear of movement, and improve participation in exercise [14]. Combined with active treatment strategies such as exercise, PNE results in positive changes in pain [15].

The need for high quality research that evaluates the effects of mind-body approaches in managing KOA pain and understanding how they may modify altered nervous system processing is needed. Our group has developed a program we call Pain Informed Movement, which is a combination of neuromuscular exercise, mind-body techniques, and PNE with the aim of improving intrinsic pain modulation in people with KOA. Although each of these components as a standalone technique can improve pain in KOA, their cumulative effect may be more substantial and has the potential to lead to an enhancement of outcomes, as each component can lead to optimization of the other. Given that the feasibility and acceptability of the Pain Informed Movement program has been previously established [16], further evaluation of this program compared to standard care is warranted. This paper presents a detailed protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) to collect pilot data, as well as initial efficacy data on the comparison of Pain Informed Movement program with neuromuscular exercise and standard OA education in people with KOA. This study has been approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board and registered on clinicaltrials.gov (ID: NCT05730829).

1.1. Study objectives and hypothesis

The objectives of this study are 1) to pilot test the procedures of this RCT and investigate the feasibility with the primary outcome of rate of follow-up, 2) assess secondary aspects of feasibility such as acceptability of the programs, rates of recruitment, adherence, compliance, as well as burden and adverse events) and 3) explore effects of Pain Informed Movement program on subjective and objective measures of KOA pain when compared to a usual conservative management strategy for people with KOA. Given the additional and improved components of the Pain Informed Movement program and it's feasibility established in the previous phase [16], we hypothesize that this pilot RCT will show feasibility of comparing the two treatment strategies, and the Pain Informed Movement program will show promising results.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

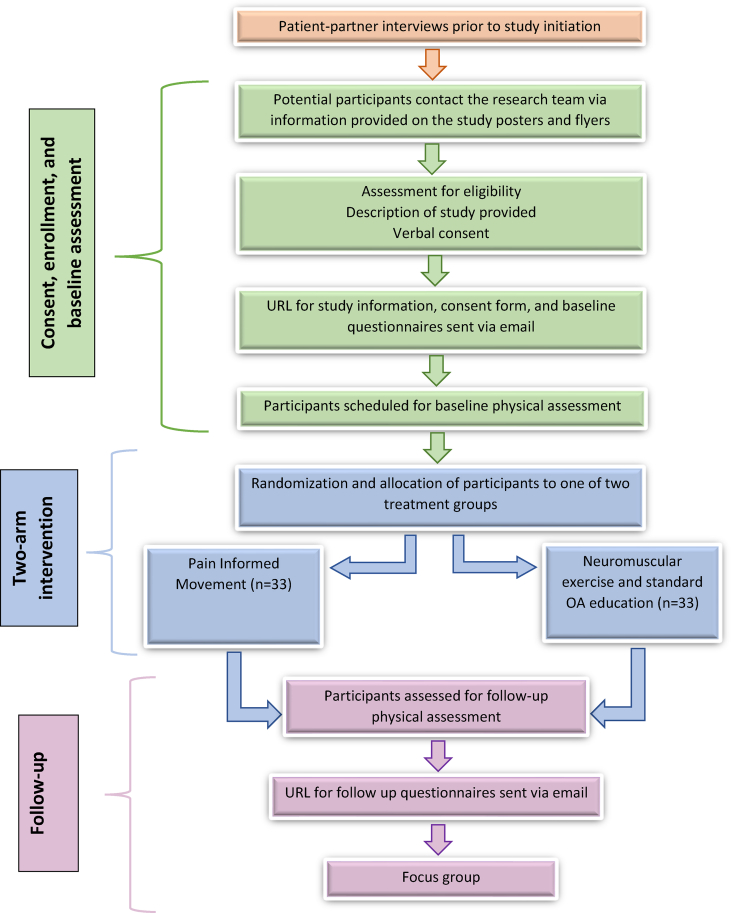

This is a pilot study with a nested qualitative component designed as a parallel, randomized, single-centre, two-arm clinical trial with a 1:1 allocation ratio. Informed consent will be obtained from all participants prior to initiating the study. All participants will be invited to complete an exit survey and take part in focus group interviews at program completion. Fig. 1 depicts the trial design. The procedures will be followed in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. The Conceptual Framework for Defining Feasibility [17] and Pilot studies and the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Intervention Trials will be used [18]. Following program completion, the study results will be reported using the extended CONSORT guideline for pilot trials as well as the TiDIER guidelines [17,19]. The study protocol is registered at clinicaltrials.gov #NCT05730829.

Fig. 1.

Flow of participants through the study.

2.2. Study participants

Sample size is based on the primary outcome of complete follow-up using the confidence interval method for calculating sample size in pilot trials [20]. We will aim for 90% follow-up but will consider the trial successful if we achieve 81%. To achieve a margin of error of 9%, with 10% added for attrition, we will require 66 participants (n = 33 per arm).

Participants will be recruited through the email lists of the McMaster University's community and research centers and their social media pages. Additionally, the study poster will be placed on other social media channels (e.g., Twitter, Facebook advertisements) and flyers will be placed in local Orthopaedic surgeon, Rheumatologist, and Physiatrists offices.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| ≥40 years of age with diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis (KOA by) a physician OR ≥45 years of age and having activity-related knee joint pain with or without morning stiffness lasting ≤30 min (NICE criteria) |

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

2.3. Screening and assessments

Potential participants will contact the research team through the contact information provided in the flyer and study poster. Screening will be conducted over the telephone and study information will be provided. Consenting and eligible participants will be a sent an individualized link to the written consent form, written study information, and baseline questionnaires. Those who pass the screening, including exercise safety, will be invited to an in-person physical assessment. Upon program completion, participants will be sent the questionnaires again (which also include the exit survey questions) and will attend a second in-person assessment of physical measures. Focus groups will be conducted to further assess the participants’ perception of the study. If a participant has bilateral KOA, the most symptomatic knee will be studied. If both knees are equally affected, the dominant knee will be studied, which is the knee with which the individual steps first when initiating gait.

2.4. Randomization and blinding

Participants will be randomized with an allocation ratio of 1:1 into one of two treatment groups (Pain Informed Movement or neuromuscular exercise and standard OA education) using a REDCap randomization module. The process of randomization will be conducted by a member of the research team who is independent of the recruitment process. Additionally, the assessors responsible for conducting baseline and follow-up assessments will be blinded and not involved in recruitment. Blinding of exercise instructors is generally not possible in studies of physical interventions (e.g., exercise) [21]. Participants will be blinded to study hypotheses and the two treatment groups. As both arms of the study are providing exercise-based interventions and education, participants will be provided limited details of each intervention arm so as to blind them from knowing which is the intervention and which is the control. This will help minimize any bias that occurs by knowledge of group assignment and perception of treatment effects.

2.5. Interventions

The intervention will start within two days of the physical assessments with participants receiving educational videos approximately 10–14 days before the first exercise session.

2.5.1. Pain Informed Movement program

Participants in this group will receive an 8 week in-person group exercise program held twice weekly, in which they will receive exercise instructions and PNE. They will also be asked to complete a third exercise session at home weekly. Participants will be provided with tracking sheets to note their compliance and progress.

The PNE component will consist of several short videos that are provided online for the first five weeks of the program (the videos are divided into short segments, each with a separate subject, totaling 20–30 min/week)). The videos will provide simple explanations of nociception processing by the nervous system, how it can be modulated through upregulation or downregulation of signals to increase or decrease pain and that pain does not accurately signify the extent of tissue damage, particularly when experiencing chronic pain. The videos will also offer techniques to reconceptualize pain and movement not as imminently dangerous. In addition, the videos will introduce and provide a demonstration of mind-body techniques that will be provided progressively each week. The mind-body techniques will include breath awareness and regulation, body awareness and muscle tension regulation, and awareness of pain related thoughts and emotions. The techniques will then be implemented in the in-person exercise sessions where participants are asked to incorporate them into the their performance of the exercises. Instructions will be provided on how to ‘nudge the edge’ of pain which is conceptualized as a balance between challenging current physical abilities during the exercises and being successful at not leaving pain provoked and/or function limited after exercise. Participants will be instructed to use breath, body tension, thoughts, and emotions as guideposts to their pain in order to successfully nudge its edge. Participants will be given the opportunity to ask questions during the in-person sessions.

The exercise component (75 min) will consist of three parts (in sequence):

Part one: the first part is the warm-up which begins with a centering practice aimed at regulating physiology. Next, warming movements of the shoulders, legs, and spine will be instructed.

Part two: of the second part is the main exercises (based on the original NEMEX-training program [4] (Table 2). This part is divided into four sections: core stability, postural orientation, lower extremity muscle strength, and functional exercises with an emphasis on proper alignment of the knee over the foot. Within each section, there are two types of exercises and three levels for progression. Participants will be instructed to complete each exercise for two to three sets of eight to 15 repetitions. For the core stability section, one exercise is instructed based on breaths. When an exercise is performed with good quality of the performance, with minimal exertion, and with control of the movement, it can be progressed by increasing repetitions or the load (going through the levels). The exercises will be performed with both the affected and the unaffected leg.

Table 2.

Details of exercises.

| Exercise circle 1: Core stability/postural function |

|---|

| Level 1 - Bridge knees maximally bent or feet under knees |

| Level 2 - Bridge Feet in front of knees to decrease support/increase effort |

| Level 3 - Bridge with one leg, do not use arms for support |

| Level 1 - Boat lean back, chest forward, knees bent, using arms to support, hold and count breaths |

| Level 2 - Boat leaning back on forearms, legs lifted, shins parallel to floor, hold and count breaths |

| Level 3 - Scissor legs from supine supported on elbows |

| Exercise circle 2: Postural orientation Back and Side lunges |

| This circle includes exercises with emphasis on an appropriate position of the joints in relation to each other (postural orientation), i.e., with the hip, knee and foot joints well aligned |

| Level 1 - Short lunge sliding step: Standing, weight-bearing on one leg with knee slightly bent. Keeping the weight in the one leg, slide the opposite foot back keeping the weight bearing hip-knee-foot aligned. |

| Level 2 - Short lunge sliding step on uneven surface (e.g. rolled mat, pillow): Standing, weight-bearing on one leg. Slide leg back to bend weight bearing knee to 135° to a moderate lunge keeping weight bearing hip-knee- foot aligned. |

| Level 3 - Low lunge step: Standing, weight-bearing on one leg. Step back as you bend weight-bearing knee to approx. 90° to moderate lunge keeping weight bearing hip-knee-foot |

| Level 1 - Short sliding side step with alignment: Standing, weight-bearing on one leg, bend knee slightly and slide the other leg to side, maintaining alignment in weight bearing leg as you slide legs back together |

| Level 2 - Short sliding side step with alignment on uneven surface: Standing, weight-bearing on one leg, bend knee partially to about 135° and slide other leg to side, maintaining alignment in weight bearing leg as step apart and back together. |

| Level 3 - Side step with alignment: Standing, weight-bearing on one leg, bend knee to about 90° and step other leg to side, maintaining alignment in weight bearing leg. Step apart and back together. |

| Exercise circle 3: Lower extremity muscle strength: Hip Abductors and Adductors; Knee flexion and extension |

| This circle includes exercises in open and closed kinetic chains to improve strength of hip and knee muscles. |

| Level 1 - Hip abductors: Standing on one leg with rubber band on other leg. Make sure there is tension on the rubber band in the resting position. Pull the band out away from the standing leg (hip abductors). Focus on positioning of the standing leg, keeping an appropriate position of the joints in the lower extremity in relation to the trunk |

| Level 2 - As previous but with increasing resistance |

| Level 3 - As previous but standing on uneven surface (folded exercise mat/pillow) |

| Level 1 - Hip adductors: Standing on one leg with rubber band on other leg. Make sure there is tension on the rubber band in the resting position. Pull the band in towards the standing leg (hip adductors). Focus on positioning of the standing leg, keeping an appropriate position of the joints in the lower extremity in relation to the trunk |

| Level 2 - As previous but with increasing resistance |

| Level 3 - As previous but standing on uneven surface (folded exercise mat/pillow) |

| Level 1 - Knee extensors: Sitting with rubber band around one foot. Pull rubber band forward (knee extensors). Make sure there is also tension in the band in resting position. |

| Level 2 - As previous but with increasing resistance |

| Level 3 - As previous but with increasing resistance |

| Level 1 - Knee flexors: Sitting with rubber band around one foot. Pull rubber band backwards (knee flexors). Make sure there is tension in the rubber band also in resting position. |

| Level 2 - As previous but with increasing resistance |

| Level 3 - As previous but with increasing resistance |

| Exercise circle 4: Functional exercises Chair sits and Stair climbing |

| This circle includes exercises resembling activities of daily life. |

| Level 1 - Chair: Start in standing and bend knees ∼45° with arms extended in front of you |

| Level 2 - Chair: Start in standing and bend knees ∼60° |

| Level 3 - Chair: Start in standing and sit back slowly to touch buttocks on chair and return to standing |

| Level 1 - Stair climbing: Step-up (concentric muscle activation) and step-down (eccentric muscle activation) on low step board, with or without slight hand support for balance. |

| Level 2 - Stair climbing: Step-up (concentric muscle activation) and step-down (eccentric muscle activation) on medium step board, with or without slight hand support for balance, option to add hand weights. |

| Level 3 - Stair climbing: Step-up (concentric muscle activation) and step-down (eccentric muscle activation) on high step board, with or without slight hand support for balance, option to add hand weights. |

Part three: the third and last part is cooldown which consists of the same warmup movements plus relaxation and guided self-reflection. Participants will be cued to use the PNE concepts and mind-body techniques during the exercise sessions.

Participants will also complete a third home session (weekly) which is facilitated by handout sheets. The exercise component will be delivered by an experienced yoga teacher with training in the integration of pain science and mindful movement.

2.5.2. Neuromuscular exercise and standard OA education

Participants in this group will receive an 8-week in-person group exercise program held twice weekly, in which they will receive exercise instructions and standard OA education. Participants will be provided with tracking sheets to note their compliance and progress.

The exercise component (60 min) of this group will be similar to that of the other group without the added mind-body techniques. Similarly, a third home session (weekly) will be facilitated by exercise handout sheets. The exercise instructions will be delivered by a physiotherapist.

The standard OA education will consist of several short videos (20–30 min/week for the first two weeks provided through online videos) and will cover the following topics: pathophysiology of OA, common OA symptoms, risk factors, the effects of exercise, and self-management tips. Participants will be given the opportunity to ask questions during the in-person sessions.

2.6. Safety

Participants will be provided with a tracking sheet to note any adverse events (AEs) throughout the study. The instructors will also monitor for adverse events during the in-person sessions. If any AE happens, participants will be instructed to tell the instructor to modify the exercises or reduce the intensity if necessary. AEs will be defined as any problem that lasts for >2 days and/or causes the participant to seek other treatment.

2.7. Primary and feasibility outcomes

The primary outcome measure is the follow-up rate (i.e., number of participants that completed the program and attended follow-up). Other feasibility outcomes include: acceptability (content, format, frequency, and duration) of the Pain Informed Movement program compared to the control group, recruitment rate, burden of procedures, adherence rate (i.e., number of participants that attended all in-person sessions), compliance to the program (i.e., number of participants that reported completion of at least three exercise sessions per week), and AEs. A priori success criteria will be used to determine feasibility and acceptability of the programs (Table 3).

Table 3.

A priori feasibility criteria.

| Outcome | A priori criteria |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Proceed | Proceed with protocol amendments | Significant amendments required | |

| Follow up | ≥90% of participants followed up at 8 weeks | ≥50% of participants followed up at 8 weeks | ≤50% of participants followed up at 8 weeks |

| Recruitment | ≥40 participants consent to participate/year | ≥30 participants consent to participate/year | <30 participants consent to participate/year |

| Compliance to exercise program | ≥80% of participants report exercise at least 3 times a week | ≥50% of participants report exercise at least 3 times a week | <50% of participants report exercise at least 3 times a week |

| Program content acceptability – usefulness | ≥50% found treatment useful (Likert ≥4/5) | ≥25% found treatment useful (Likert ≥4/5) | <25% found treatment useful (Likert ≥4/5) |

| Program content acceptability – frequency | ≥50% found frequency acceptable (Likert ≥4/5) | ≥25% found frequency acceptable (Likert ≥4/5) | <25% found frequency acceptable (Likert ≥4/5) |

| Program content acceptability – duration | ≥50% found duration acceptable (Likert ≥4/5) | ≥25% found duration acceptable (Likert ≥4/5) | <25% found duration acceptable (Likert ≥4/5) |

| Format acceptability – delivery | ≥50% found treatment delivery (in-person and home) acceptable (Likert ≥4/5) | ≥25% found treatment delivery acceptable (Likert ≥4/5) | <25% found treatment delivery acceptable (Likert ≥4/5) |

| Adherence to in person treatment | ≥75% of participants attended all in person treatment sessions | ≥50% of participants attended all in person treatment sessions | ≤25% of participants attended all in person treatment sessions |

| Burden (0 = no burden, 10 = most burden) | Burden of completing questionnaires and physical tests <3/10 for ≥75% of participants | Burden of completing questionnaires and physical tests <3/10 for ≥50% of participants | Burden of completing questionnaires and physical tests <3/10 for ≤25% of participants |

| Adverse events | No adverse events or only mild transient (e.g., pain increase) for ≥75% of participants | No adverse events or only mild transient (e.g., pain increase) for ≥50% of participants | No adverse events or only mild transient (e.g., pain increase) for ≤25% of participants |

2.8. Secondary outcomes and descriptive data

Participant characteristics such as age, sex, gender, education, marital status, race, number of people in household, height, and weight will be collected. A list of secondary outcomes is provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Secondary outcomes.

| Outcome | Tool | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Comorbidities | Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) | To assesses the presence of 19 comorbidities in participants. The CCI has been used in many patient populations including knee osteoarthritis (KOA) [22]. |

| Central sensitization | Mechanical Temporal Summation (TS) | We will use a 512 mN weighted probe applied at the volar wrist opposite to the index knee. Participants will be asked to rate their pain between 0 and 100 [23]. Then, the same stimulus will be applied 10 times at the rate of 1/second (guided by a metronome) and they are asked again to rate their pain. TS is defined as being present when, compared with the initial trial, the participant reports increased pain following the second trial [23]. The validity of mechanical TS has been reported in people with KOA [23]. |

| Endogenous pain modulation | Conditioned Pain Modulation (CPM) | CPM will be assessed in the following steps [24]: 1) at the anterior shin on the unaffected knee, an ascending measure of pressure pain threshold (PPT) will be evaluated. 2) At the opposite volar forearm, a conditioning stimulus in the form of forearm ischemia using a blood pressure cuff and squeezing a stress ball until a pain rating of 4/10 is reached, 3) PPT at the anterior shin will be repeated with the cuff remaining inflated [24], 4) an index will be created by calculating the percent efficiency of CPM (%CPM) as PPT2/PPT1, multiplied by 100; whereby %CPM ≤100 indicates inefficient pain modulation [25]. CPM testing has demonstrated good intra-session reliability [26]. |

| Pain intensity | Numeric Rating Scale | Average pain intensity in the past 24 h, past week, and worst pain in the past 24 h will be recorded. Questions are rated on an 11-point scale where patients select a rating between 0 and 10 with zero representing ‘no pain’ and 10 representing the ‘worst imaginable pain’ [27].The Numeric Rating Scale is reported to have excellent inter-rater reliability and acceptable validity in people with KOA [28]. |

| Pain catastrophizing | Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) | The PCS [29] is a 13-item self-reporting instrument for catastrophizing in the context of actual or anticipated pain, with higher scores indicating higher pain catastrophizing. The validity of the PCS for measuring pain catastrophizing in people with KOA has been reported [30]. |

| Chronic pain self-efficacy | Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease 6-item scale (SEMCD-6) | Higher reported scores on the SEMCD-6 indicates higher self-efficacy [31]. The SEMCD-6 has high internal consistency with significant correlations with other health outcomes [32]. |

| Anxiety and depressive symptoms | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Higher scores on the HADS [33] indicate increased severity of anxiety and depression symptoms. The HADS is a brief and reliable measure of emotional distress in general in chronic populations [34]. Validity and reliability of the HADS have been previously established [34]. |

| Fear of movement | Brief Fear of Movement Scale for Osteoarthritis (BFMSO) | The BFMSO has 6 items that are derived from the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK) and uses a 4-point Likert scale with higher values indicating higher levels of kinesiophobia [35]. The BFMSO has been reported to have adequate validity [35]. |

| Knee injury and outcomes | Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) | The KOOS pain and function in daily living and QoL subscales will be used to assess self-reported opinions about patients' knee and associated problems. Scores range from 0 to 100 with zero representing extreme knee problems and 100 representing no knee problems [36]. KOOS has adequate internal consistency and validity in people with KOA [37]. |

| Type of KOA pain | Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP) | The ICOAP knee version will be used to assess the different types of knee pain participants are experiencing [38]. The ICOAP knee version has two sections: 1) ‘constant pain’ has 5 items that asks about pain that is present all the time, and 2) the ‘intermittent pain’ has 6 items that asks about pain that comes and goes. The psychometric properties of the ICOAP such as reliability and validity have been previously established [39]. |

| Other painful body parts | Body diagram | Participants will be asked to indicate any other areas where they experience pain (e.g., neck, shoulders, back) on a body diagram. Body diagrams have shown to be a reliable method for indication of painful body parts [40]. |

| Functional leg strength | 30 s sit-to-stand test | The 30 Second Sit to Stand Test will be used as a performance test [41]. The maximum number of chair stand repetitions completed during a 30 s interval will be noted. A standard chair height will be used for all participants. The 30 Second Sit to Stand Test has been reported to be a reliable measure of functional leg strength and endurance [41]. |

| Brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF) | Blood analysis (blood draws under fasting conditions) | Altered levels of BDNF are involved in the pathophysiology of chronic pain [42]. NGF have been shown to be elevated in a wide variety of chronic pain conditions including KOA [43]. Five ml of blood will be drawn for analysis of BDNF and NGF. Serum levels of BDNF, diluted 1:100, will be measured using Biosensis Human/Mouse/Rat BDNF ELISA kits read on a Spectramax i3 spectrophotometer. Serum levels of NGF will be measured in duplicate, after diluting 2× in Reagent Diluent, with R&D Systems Human beta-NGF DuoSet ELISA kits read on a Multiskan Go spectrophotometer. Collected samples will be stored at −80C. |

| Medication use | Survey question | Participants will be asked to indicate any medication that they take on a regular schedule including prescription medications, non-prescription, over the counter, vitamins, herbal, and alternative medicines. |

| Perspective on knee replacement surgery | Survey question | Three questions will be asked: 1. Are your knee symptoms so severe that you wish to undergo knee replacement surgery [44]? 2. Do you think knee replacement surgery is eventually inevitable [45]? 3. In your opinion, what factor(s) can lead to better outcomes after knee replacement surgery? |

| Perspectives on effectiveness of components of the interventions | Survey question | Participants will be asked to rank the effectiveness of the intervention components for pain management that they received. i.e. mind-body techniques, PNE and strengthening exercises vs OA education and strengthening exercises. |

2.9. Exit survey and focus group

At follow-up, a satisfaction survey will be conducted. Participants who indicated upon initially consenting to the study that they would like to participate in a focus group will be contacted. Qualitative description will be used to explore participants’ experience and perceptions of the feasibility and acceptability of the Pain Informed Movement program as well as the standard treatment as well as the procedure for the entire study. An interview guide developed by patients and practitioners will be used. The focus groups will be conducted virtually consisting of six to eight participants and will last about 60–90 min. The session will be recorded, and transcripts will be produced to ensure accuracy of the responses.

2.10. Data integrity

The health information collected in this study will be kept confidential on a secure REDCap platform maintained by McMaster University. To ensure confidentiality, each participant will be given a unique identification number. At the end of the study, the anonymized data will be kept and will comprise a resource database. The researchers and the ethics board may access the study records to monitor the research and verify the accuracy of study information. No records with identifying information will be allowed to leave the principle investigator's office. Study information will be kept for 10 years, then will be permanently destroyed.

2.11. Analysis

Descriptive statistics will be used to report feasibility outcomes.

The quantitative analysis of secondary outcomes will be by intention-to-treat principles. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) will be used to assess the amount of change in outcome measures and compare them between the two groups using means and 95% CIs. Similarly, within group differences will be analyzed using the paired sample's t-test and will be reported using means and 95% CIs. Where possible we will also report minimally important difference.

The transcripts of the focus group interviews will be analyzed using thematic content analysis to identify suggestions for program modification [46]. Line-by-line reading of the transcripts will be performed and thematic patterns will be explored. Once themes and patterns are identified, each meaningful segment of text will be assigned a conceptual code.

3. Discussion

One of the leading causes of pain in older adults worldwide is KOA [2]. Unfortunately, currently there are no disease modifying medications available, surgery is performed at the late stages with a considerable percentage of people experiencing unfavorable outcomes [47], and we have limited conservative pain management strategies. Given the importance of finding more effective pain management strategies for KOA pain, a mechanism-informed approach is needed and recommended [48] to further our understanding of why and how certain treatments work to improve precision medicine. While it has become clear that there are alterations in neural processing in patients with KOA [23], intrinsic pain modulation has largely not been incorporated into treatment strategies.

In the previous phase of this study, we established the feasibility of the Pain Informed Movement program consisting of neuromuscular exercises combined with PNE and mind body techniques of breath awareness and regulation, muscle tension regulation, awareness of pain related thoughts and emotions, relaxation, body awareness. In this second phase, a pilot RCT will be conducted to explore the feasibility of this program compared with the standard recommended treatment of neuromuscular exercise and standard OA education. Additionally, we will be assessing the preliminary results regarding the effects of the program on pain, central sensitization, pain modulation, psychological factors, self-efficacy, knee associated problems, functional leg strength, and serum Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) and Nerve Growth Factor (NGF).

This study will lay the foundation to inform a larger multi-site RCT to assess the program's effectiveness and understanding of its underlying mechanisms. We are ultimately interested in understanding whether the Pain Informed Movement program enhances endogenous pain modulation measured by conditioned pain modulation (CPM) and whether this effect mediates the relationship between the intervention and change in pain. The larger RCT will contribute to the clinical recommendations for management of OA pain for clinicians across multiple sectors. We anticipate that this study will be completed by December 2023.

Author contributions

All authors: (1) made substantial contributions to the conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) participated in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and (3) gave final approval of the version to be published.

Funding

SM is supported by a Fellowship from the Michael DeGroote Institute for Pain Research and Care. KLB is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Fellowship. The study was funded by The Arthritis Society STAR 20-0000000005.

Declaration of competing interest

SM and MF nothing to declare. LCC is an editorial board member of Pain Medicine Journal and has received consulting fees from EPG Health and the Canadian Orthopaedic Foundation. NP has received grants and travel support from Lifemark Canada and the Chronic Pain Centre of Excellence, royalties from Singing Dragon publishers, consulting fees from the British Columbia Massage therapists, Alberta Pain Education Collaborative, The Primary Care Network of Alberta and Bill Nelems Pain center podcasts. KM has received grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Research Institute of St. Joseph's Hamilton, The Canadian Orthopaedic Foundation and Biotalent; is on a data safety and monitoring board at the University of Calgary and committees at Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research and the Society for Clinical Trials. KLB has received grants on OA from the National Health and Medical Research Council, Medical Research Futures Fund and Medibank Private, and royalties from Wolters Kluwer for UpToDate Knee osteoarthritis guidelines.

Acknowledgments

None.

Handling Editor: Professor H Madry

Contributor Information

Shirin Modarresi, Email: smodarre@uwo.ca.

Neil Pearson, Email: neil@paincareu.com.

Kim Madden, Email: maddenk@mcmaster.ca.

Kim L. Bennell, Email: k.bennell@unimelb.edu.au.

Margaret Fahnestock, Email: fahnest@mcmaster.ca.

Tuhina Neogi, Email: tneogi@bu.edu.

Lisa C. Carlesso, Email: carlesl@mcmaster.ca.

References

- 1.Wilkie R., Blagojevic-Bucknall M., Jordan K.P., Lacey R., McBeth J. Reasons why multimorbidity increases the risk of participation restriction in older adults with lower extremity osteoarthritis: a prospective cohort study in primary care. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65:910–919. doi: 10.1002/acr.21918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bannuru R.R., Osani M.C., Vaysbrot E.E., Arden N.K., Bennell K., Bierma-Zeinstra S.M.A., et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27:1578–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolasinski S.L., Neogi T., Hochberg M.C., Oatis C., Guyatt G., Block J., et al. 2019 American college of rheumatology/arthritis foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2020;72:149–162. doi: 10.1002/acr.24131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ageberg E., Roos E.M. Neuromuscular exercise as treatment of degenerative knee disease. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2015;43:14–22. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fransen M., McConnell S., Harmer A.R., Van der Esch M., Simic M., Bennell K.L. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a Cochrane systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015;49:1554–1557. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu K., Robbins S.R., McDougall J.J. Osteoarthritis: the genesis of pain. Rheumatology. 2018;57:iv43–iv50. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taibi D.M., Vitiello M.V. A pilot study of gentle yoga for sleep disturbance in women with osteoarthritis. Sleep Med. 2011;12:512–517. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearson N., Prosko S., Sullivan M., Taylor M.J. White paper: yoga therapy and pain-how yoga therapy serves in comprehensive integrative pain management, and how it can do more. Int. J. Yoga Therap. 2020;30:117–133. doi: 10.17761/2020-D-19-00074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busch V., Magerl W., Kern U., Haas J., Hajak G., Eichhammer P. The effect of deep and slow breathing on pain perception, autonomic activity, and mood processing--an experimental study. Pain Med. 2012;13:215–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saoji A.A., Raghavendra B.R., Manjunath N.K. Effects of yogic breath regulation: a narrative review of scientific evidence. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2019;10:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russo M.A., Santarelli D.M., O'Rourke D. The physiological effects of slow breathing in the healthy human. Breathe. 2017;13:298–309. doi: 10.1183/20734735.009817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlereth T., Birklein F. The sympathetic nervous system and pain. Neuro. Molecular Med. 2008;10:141–147. doi: 10.1007/s12017-007-8018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Majeed M.H., Ali A.A., Sudak D.M. Mindfulness-based interventions for chronic pain: evidence and applications. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2018;32:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawford B.J., Bennell K.L., Hall M., Egerton T., Filbay S., McManus F., et al. Removing pathoanatomical content from information pamphlets about knee osteoarthritis did not affect beliefs about imaging or surgery, but led to lower perceptions that exercise is damaging and better osteoarthritis knowledge: an online randomised contro. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2022:1–27. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2022.11618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsen J.B., Skou S.T., Arendt-Nielsen L., Simonsen O., Madeleine P. Neuromuscular exercise and pain neuroscience education compared with pain neuroscience education alone in patients with chronic pain after primary total knee arthroplasty: study protocol for the NEPNEP randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21:218. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-4126-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlesso L. Clinicaltrials.gov; 2022. Feasibility of Pain Informed Movement for Knee OA.https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04954586 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eldridge S.M., Chan C.L., Campbell M.J., Bond C.M., Hopewell S., Thabane L., et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ. 2016;355:i5239. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan A.-W., Tetzlaff J.M., Altman D.G., Laupacis A., Gøtzsche P.C., Krleža-Jerić K., et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013;158:200–207. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffmann T.C., Glasziou P.P., Boutron I., Milne R., Perera R., Moher D., et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thabane L., Ma J., Chu R., Cheng J., Ismaila A., Rios L.P., et al. A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why and how. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2010;10:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moseley A.M., Herbert R.D., Sherrington C., Maher C.G. Evidence for physiotherapy practice: a survey of the physiotherapy evidence database (PEDro) Aust. J. Physiother. 2002;48:43–49. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collins J.E., Katz J.N., Dervan E.E., Losina E. Trajectories and risk profiles of pain in persons with radiographic, symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22:622–630. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neogi T., Frey-Law L., Scholz J., Niu J., Arendt-Nielsen L., Woolf C., et al. Sensitivity and sensitisation in relation to pain severity in knee osteoarthritis: trait or state? Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015;74:682–688. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yarnitsky D. Role of endogenous pain modulation in chronic pain mechanisms and treatment. Pain. 2015;156:S24–S31. doi: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460343.46847.58. Suppl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yarnitsky D., Arendt-Nielsen L., Bouhassira D., Edwards R.R., Fillingim R.B., Granot M., et al. Recommendations on terminology and practice of psychophysical DNIC testing. Eur. J. Pain. Apr. 2010;14 doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.02.004. England, 339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis G.N., Heales L., Rice D.A., Rome K., McNair P.J. Reliability of the conditioned pain modulation paradigm to assess endogenous inhibitory pain pathways. Pain Res. Manag. 2012;17:98–102. doi: 10.1155/2012/610561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez C.S. Pain measurement in the elderly: a review., Pain Manag. Nurs. Off. J. Am. Soc. Pain Manag. Nurses. 2001;2:38–46. doi: 10.1053/jpmn.2001.23746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alghadir A.H., Anwer S., Iqbal A., Iqbal Z.A. Test-retest reliability, validity, and minimum detectable change of visual analog, numerical rating, and verbal rating scales for measurement of osteoarthritic knee pain. J. Pain Res. 2018;11:851–856. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S158847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sullivan M.J.L., Bishop S.R., Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol. Assess. 1995;7:524–532. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ong W.J., Kwan Y.H., Lim Z.Y., Thumboo J., Yeo S.J., Yeo W., et al. Measurement properties of Pain Catastrophizing Scale in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021;40:295–301. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorig K.R., Sobel D.S., Ritter P.L., Laurent D., Hobbs M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Effect Clin. Pract. 2001;4:256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ritter P.L., Lorig K. The English and Spanish Self-Efficacy to Manage Chronic Disease Scale measures were validated using multiple studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014;67:1265–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zigmond A.S., Snaith R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smarr K.L., Keefer A.L. Measures of depression and depressive symptoms: beck depression inventory-II (BDI-II), center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D), geriatric depression scale (GDS), hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), and patient health questionn. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(Suppl 1):S454–S466. doi: 10.1002/acr.20556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shelby R.A., Somers T.J., Keefe F.J., DeVellis B.M., Patterson C., Renner J.B., et al. Brief fear of movement scale for osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:862–871. doi: 10.1002/acr.21626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roos E.M., Roos H.P., Lohmander L.S., Ekdahl C., Beynnon B.D. Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS)--development of a self-administered outcome measure. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 1998;28:88–96. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1998.28.2.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collins N.J., Prinsen C.A.C., Christensen R., Bartels E.M., Terwee C.B., Roos E.M. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): systematic review and meta-analysis of measurement properties. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24:1317–1329. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hawker G.A., Stewart L., French M.R., Cibere J., Jordan J.M., March L., et al. Understanding the pain experience in hip and knee osteoarthritis--an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hawker G.A., Davis A.M., French M.R., Cibere J., Jordan J.M., March L., et al. Development and preliminary psychometric testing of a new OA pain measure--an OARSI/OMERACT initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhon D.I., Lentz T.A., George S.Z. Unique contributions of body diagram scores and psychosocial factors to pain intensity and disability in patients with musculoskeletal pain. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2017;47:88–96. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2017.6778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dobson F., Hinman R.S., Roos E.M., Abbott J.H., Stratford P., Davis A.M., et al. OARSI recommended performance-based tests to assess physical function in people diagnosed with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:1042–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Obata K., Noguchi K. BDNF in sensory neurons and chronic pain. Neurosci. Res. 2006;55:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stoppiello L.A., Mapp P.I., Wilson D., Hill R., Scammell B.E., Walsh D.A. Structural associations of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:3018–3027. doi: 10.1002/art.38778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dell'Isola A., Jönsson T., Rolfson O., Cronström A., Englund M., Dahlberg L. Willingness to undergo joint surgery following a first-line intervention for osteoarthritis: data from the better management of people with osteoarthritis register. Arthritis Care Res. 2021;73:818–827. doi: 10.1002/acr.24486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grace T.R., Eralp I., Khan I.A., Goh G.S., Siqueira M.B., Austin M.S. Are patients with end-stage arthritis willing to delay arthroplasty for payer-mandated physical therapy? J. Arthroplasty. 2022;37:S27–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2021.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiger M.E., Varpio L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med. Teach. 2020;42:846–854. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beswick A.D., Wylde V., Gooberman-Hill R., Blom A., Dieppe P. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open. 2012;2 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kan L., Zhang J., Yang Y., Wang P. The effects of yoga on pain, mobility, and quality of life in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Evid. Based. Complement. Alternat. Med. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/6016532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]