Abstract

A typing procedure for Staphylococcus aureus was developed based on improved PCR amplification of the coagulase gene and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of the product. All coagulase-positive staphylococci produced a single PCR amplification product of either 875, 660, 603, or 547 bp. Those strains of epidemic methicillin-resistant S. aureus 16 (EMRSA-16) studied all gave a product of 547 bp. PCR products were digested with AluI and CfoI, and the fragments were separated by gel electrophoresis. Ten distinct RFLP patterns were found among 85 isolates of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and 10 propagating strains (PS) of methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) examined. RFLP patterns 1, 2, and 3 were specific to strains of EMRSA-3, -15, and -16, respectively. By contrast, RFLP patterns 4 and 5 were seen with a heterogeneous collection of strains, together with drug-resistant forms of S. aureus isolated in Europe and four propagating strains used for the international phage set. RFLP pattern 6 was given by the Airedale isolate and PS 95. RFLP pattern 7 encompassed EMRSA-2 (isolate 331), PS 94, and PS 96. An isolate from Germany gave RFLP pattern 8. Eight strains of MSSA gave patterns similar to those of methicillin-resistant strains (RFLP patterns 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7), but two, PS 42E and PS 71, gave unique RFLP patterns 9 and 10, respectively. The coagulase gene PCR products for 24 isolates of MRSA and two isolates of MSSA were sequenced for both strands. The sequences were aligned, and evolutionary lineages were inferred based on pairwise distances between isolates.

Resistance to methicillin was first described for Staphylococcus aureus in 1960, shortly after the introduction of the drug into clinical practice (20). Since then, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) has become a widely recognized cause of morbidity and mortality throughout the world (16).

Accurate and rapid typing of S. aureus is crucial to the control of infectious organisms (37), and numerous methods have been described elsewhere (8, 19, 28). A bacteriophage typing scheme for S. aureus has been agreed on internationally since 1951, but although it remains a cost-effective approach to typing the large number of referred isolates, it has some limitations. The reagents are not commercially available, and in some instances and certain parts of the world, MRSA strains are nontypeable with phages (5). Of the other methods, plasmid analysis has drawbacks, since the plasmids may be absent from isolates, may vary in size, or may be readily lost (18), and antibiogram schemes are often uninformative, as many strains are multiply drug resistant (6).

Recently, several investigators have described DNA-based techniques for typing strains (13, 17, 34, 40). Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) is now recognized as being the most discriminatory method for gene typing strains of S. aureus, and it has been used to investigate nosocomial outbreaks (4, 39). However, PFGE is costly and technically complex and lacks an agreed criterion for the interpretation of banding patterns (4, 9). Furthermore, for most national reference centers, it is not practical to use PFGE to type the large numbers of referred isolates.

In the 1980s, epidemic methicillin-resistant S. aureus 1 (EMRSA-1) was the principal MRSA strain identified by phage typing in England (27). By 1986, a further 13 EMRSA strains were recognized (EMRSA-2 to EMRSA-14). Recently, EMRSA-15 and EMRSA-16 were described (12, 31). Currently, the major United Kingdom EMRSA strains are 3, 15, and 16. In 1996, these comprised approximately 50% of the isolates referred for phage typing to our staphylococcus reference service (1). However, some strains phage typed weakly or not at all, even at a 100× routine test dilution (RTD). To confirm phage type and/or to answer particular epidemiological questions, PFGE has been used periodically, and yet an alternative rapid and cost-effective confirmatory test would be of value in clinical and reference centers.

Coagulase is produced by all strains of S. aureus (24). Its production is the principal criterion used in the clinical microbiology laboratory for the identification of S. aureus in human infections, and it is thought to be an important virulence factor. The sizes and DNA restriction endonuclease site polymorphisms at the 3′ coding region of the coagulase gene have been utilized in PCR-based restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of S. aureus (15, 25, 26, 29, 38, 39).

We describe here a coagulase gene-based PCR RFLP technique that differentiated among the major current United Kingdom EMRSA strains, i.e., EMRSA-3, EMRSA-15, and EMRSA-16, as well as minor epidemic strains. The PCR primers were designed to encompass the entire 3′ repeat elements, thereby avoiding the variable regions within the coagulase gene. Comparisons between DNA sequence data from the 3′ variable region of the coagulase gene then allowed phylogenetic groups to be identified and permitted inferences to be drawn about some of the lineages of S. aureus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Bacterial strains were examined under a code that was broken upon completion of the analysis of the results. Eighty-five S. aureus strains representing EMRSA-1 to -16, including the original Jevons strain (NCTC 10442) and two duplicates, together with 10 methicillin-sensitive S. aureus propagating strains (PS), were studied (Table 1) (2, 12, 31, 33, 34, 41). Negative controls comprising three coagulase-negative staphylococcal species, S. epidermidis (NCTC 11047), S. haemolyticus (NCTC 11042), and S. saprophyticus (NCTC 7292), were also included. Bacteria were grown overnight on blood agar plates at 37°C, in an aerobic atmosphere. Stock clinical cultures were maintained in blood glycerol (16% [vol/vol]) broth on Preserver Beads (Technical Service Consultants, Heywood, Lancashire, United Kingdom) at −70°C.

TABLE 1.

Strains of S. aureus studied and their phenotypic features

| Strain (isolate [no. of isolates])e | Phage type(s) | Supplementary phage(s) | Toxin productiona | Ureaseb | Protein Ac |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMRSA-1 [4] | 85/88A/932 | 616/617/620/622/626/630 | A | ++ | ± |

| EMRSA-1 (CRF 616 [1]) | 85+/88A/932 | 620+/622/617/626/630 | A | ++ | ± |

| EMRSA-1 (QC 21 [1]) | 85 | 620+/622/617/626/630 | A | + | ± |

| EMRSA-2 [6] | 80/85/90/932 | 616/617/622/626/630 | A | − | ++ |

| EMRSA-2 (QC 15 [1]) | 80/85/90/932 | 616/617/622/626/630 | A | − | ++ |

| EMRSA-3 [10] | 75/83A/932 | 618+/620+/623+/629+ | -ve | − | ++ |

| EMRSA-4 [4] | 85/90/932 | 623+ | A | + | ++ |

| EMRSA-5 [3] | 77/84 | 618/620 | A, B, C | ++ | + |

| EMRSA-6 [4] | 90/932 | NTd | A | − | ++ |

| EMRSA-7 [2] | 85inh | NT | A, C | + | ++ |

| EMRSA-8 [3] | 83A/83C/932 | 620+/617/622/630 | -ve | ++ | ++ |

| EMRSA-9 [2] | 77/84/932 | 620+/622/617/626/630 | -ve | ++ | + |

| EMRSA-10 [2] | 77/83A/29/75/85 | 626+/617/618/622/630 | A, B | − | + |

| EMRSA-11 [2] | 84 | 617/618/620/622 | A | ++ | ++ |

| EMRSA-12 [3] | 75/83A/83C/932 | 617/622/629 | -ve | − | ++ |

| EMRSA-12 (QC 03 [1]) | 75/83A/54/75 | 617/622/629 | -ve | − | ++ |

| EMRSA-13 [2] | 29/83C/932 | 620+/629/630 | -ve | ++ | ++ |

| EMRSA-14 [2] | 29+/6/47/54/90/932 | 629/630 | -ve | − | + |

| EMRSA-15 [11] | 75+ | NT | C | − | ++ |

| EMRSA-15 (91/11046 [1]) | 75+ | NT | C | − | ± |

| EMRSA-16 [10] | 29inh/52inh/75/77/83A | 618± | A, TSST-1 | ++ | ± |

| EMRSA-16 (K 06 [1]) | 29inh/52inh/75/77/83A | 618± | A, TSST-1 | ++ | ± |

| EMRSA-16 (QC 01 France [1]) | 77/84 | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested |

| EMRSA-16 (QC 07 France [1]) | 77/84 | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested |

| EMRSA-16 (211 Spain [1]) | 29/77/84/932 | 618 | A | ++ | ± |

| EMRSA-16 (212 Spain [1]) | 29/77/84/932 | NT | A | ++ | ± |

| EMRSA-16 (QC 04 Germany [1]) | 84 | 618/620 | A | ++ | ++ |

| EMRSA-16 (94/14103 Germany [1]) | 54 | 625± | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested |

| NCTC 10442T [1] | 47/53/54/75/77/84/85 | 616/617/618/622/623/625/626/629/630 | B | Not tested | ++ |

| PS 6, III, NCTC 8509 [1] | 6/47/53/54/75/83A | 616/617/620/622/623/626 | -ve | ++ | Not tested |

| PS 29, I, NCTC 8331 [1] | 29 | NT | C, TSST-1 | ++ | Not tested |

| PS 42E, III, NCTC 8357 [1] | 42E | NT | -ve | ++ | Not tested |

| PS 52, I, NCTC 8507 [1] | 52 | NT | -ve | ++ | Not tested |

| PS 53, III, NCTC 8511 [1] | 53/54/75/77/84/85 | 617/622 | A, B | ++ | Not tested |

| PS 71, II, NCTC 9315 [1] | 3C/55/71 | NT | TSST-1 | ++ | Not tested |

| PS 75, III, NCTC 8354 [1] | 53/75/77/84/85 | 618/626 | B | ++ | Not tested |

| PS 94, V, NCTC 10970 [1] | 94/96 | NT | B | ++ | Not tested |

| PS 95, misc, NCTC 10971 [1] | 95 | NT | B | ++ | Not tested |

| PS 96, V, NCTC 10972 [1] | 94/96 | NT | B | ++ | Not tested |

Toxins A, B, and C and/or TSST-1; -ve, no toxin produced.

−, negative; +, positive; ++, strongly positive.

±, weakly positive; +, positive; ++, strongly positive.

NT, non-phage-typeable.

PS, methicillin-sensitive S. aureus propagating strain for the international set; I, II, III, and V, phage groups; misc, miscellaneous phage group; T, type strain (20) obtained from the National Collection of Type Cultures, Public Health Laboratory Service, London, United Kingdom.

Bacteriophage typing.

This was done by the method described by Blair and Williams (5) at the RTD and a 100× RTD with the current set of international phages (3) and supplementary phages (32).

Enterotoxin production.

Isolates were examined for the production of enterotoxins A, B, and C and toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1) by reverse passive latex agglutination according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Oxoid Unipath).

Protein A production.

A rapid, semiquantitative dot blot analysis was employed (33).

Urease production.

Conventional urea slopes were inoculated with 100 to 200 μl of an overnight broth culture with a Pasteur pipette to ensure that the slope was inoculated evenly. Slopes were incubated at 37°C for up to 7 days (11).

DNA preparation.

Two methods were used to prepare DNA from strains of S. aureus.

(i) Lysostaphin-sodium chloride-cetyltrimethylammonium bromide.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated as described by Jones (21), with modifications. The bacteria were harvested from one-half the area of a blood agar plate, suspended in 1 ml of TE-glucose (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 1.0% [wt/vol] d-glucose), and centrifuged at 7,500 × g for 5 min. The cells were resuspended in 100 μl of lysostaphin (1 mg/ml in TE-glucose; Sigma)–50 μl of lysozyme (50 mg/ml in TE-glucose; Sigma) and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Eighty microliters of NaCl-cetyltrimethylammonium bromide solution (0.7 M NaCl, 10% [wt/vol] cetyltrimethylammonium bromide; Sigma) was added with mixing and incubated at 65°C for 10 min. Sodium chloride (100 μl of a 5 M stock solution), sodium dodecyl sulfate (30 μl of 10% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate; Sigma), and proteinase K (4 mg of proteinase K; Sigma) were added with mixing and incubated at 55°C for 30 min. The lysate was extracted with equal volumes of phenol-chloroform, and the DNA was precipitated from the aqueous phase with 1 volume of isopropanol and resuspended in 100 μl of sterile distilled PCR-quality water (Sigma). The DNA concentration was determined by UV spectrophotometry at A260, and the extract was stored at 4°C. Extraction time was 1 to 2 days. Approximately 50 to 100 ng of DNA was taken for PCR amplification.

(ii) Chelex extraction.

A half-loopful (approximately 25 μl) of bacterial growth was removed from a blood agar plate, suspended in 1 ml of TE-glucose, and centrifuged at 7,500 × g for 5 min. The cells were resuspended in 100 μl of lysostaphin solution plus 50 μl of lysozyme and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. One hundred microliters of a 5 M NaCl solution and 30 μl of proteinase K were added, and the lysate was incubated at 55°C for 30 min. Five microliters of the lysate was diluted in 45 μl of PCR-quality water. Ten microliters of Chelex 100 resin (sodium form; 100/200 mesh size; final concentration, 5% [wt/vol]; pH 7.0; Sigma)–Nonidet P-40 (Sigma; final concentration, 0.4% [vol/vol]) solution was added and incubated at 55°C for 30 min. The lysate was then overlayered with 2 drops of mineral oil (Sigma) and heated at 99°C for 20 min to denature the proteinase K. One microliter of lysate was taken for PCR amplification.

PCR amplification of the coagulase (coa) gene.

An oligonucleotide primer pair was designed by using the program Primer (C. W. Dieffenbach, Department of Surgery and Pathology, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md.). To encompass the entire 3′ repeat elements and avoid the variable regions within the coagulase gene primer sequences, 5′ATA GAG ATG CTG GTA CAG G3′ (1513 to 1531; nucleotide numbering according to the work of Kaida et al. [23]; MRSA 213, accession no. X16457) and 5′GCT TCC GAT TGT TCG ATG C3′ (2188 to 2168) were chosen. Each amplification in sterile thin-walled glass capillaries (Idaho Technologies, Idaho Falls, Idaho) comprised DNA template, 75 pmol of each primer, 50 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP), 1× buffer (Gibco BRL), 3.0 mM MgCl2, 1× bovine serum albumin (250 μg/ml; BioGene Limited, Kimbolton, Bedfordshire, United Kingdom), and 12.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Gibco BRL). Filter-sterilized (0.22-μm pore size) PCR-quality water (Sigma) was added to a final volume of 50 μl. Thermal cycling took place on a hot-air Rapidcycler (Idaho Technologies) following an initial denaturation at 94°C for 45 s. The cycling proceeded for 30 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 57°C for 15 s, and 70°C for 15 s with a final step at 72°C for 2 min. The size of the PCR product (5-μl aliquot) was determined by comparison to the φX174 DNA/HaeIII markers (Bio-Rad Laboratories) by electrophoresis on 1.0% (wt/vol) agarose gels.

DNA restriction endonuclease analysis of the PCR-amplified coagulase gene.

Approximately 500 ng (7 to 10 μl) of PCR product was digested with 2 U of restriction endonuclease (AluI, CfoI, HinfI, and SacI; Boehringer Mannheim) at 37°C for 1 h 30 min. Twenty microliters of digested PCR product was analyzed by electrophoresis on 2.75% (wt/vol) agarose gels (FMC BioProducts).

DNA sequencing of the PCR-amplified coagulase gene.

The 875- to 550-bp PCR-amplified fragments were purified according to the method of Zhen and Swank (42). PCR products were directly sequenced on both overlapping strands with DyeDeoxy Terminator kits (Applied Biosystems-Perkin-Elmer) according to the manufacturer’s protocol with a 377 DNA sequencer. The primers used were those for PCR amplification.

Data analysis.

Sequences were aligned against S. aureus 213 (accession no. X16457 [23]) and 8325-2 (accession no. Z33404 [30]) by using the program Multalin (10) (Cherwell Scientific Publishing Limited, Oxford, United Kingdom). Those base positions that could not be aligned unambiguously were removed. A total of 530 nucleotide bases for 28 strains comprised the final alignment; this is available from us on request. Evolutionary analyses were carried out with PHYLIP (J. Felsenstein, University of Washington, Seattle). The reliability of tree nodes was assessed by analyzing 1,000 data sets. Pairwise distances between sequences were inferred under the Jukes and Cantor (22) one-parameter model. Trees were constructed by using neighbor joining (NEIGHBOR [35]) and the algorithm of Fitch and Margoliash (FITCH [14]). A majority rule consensus tree was computed with the CONSENSE program. The bootstrap percentages quoted in the legend to Fig. 3 are the percentages of times that a taxon to the right of that node occurred, and they provide some indication of the stability of the branching order and the phylogenetic groupings.

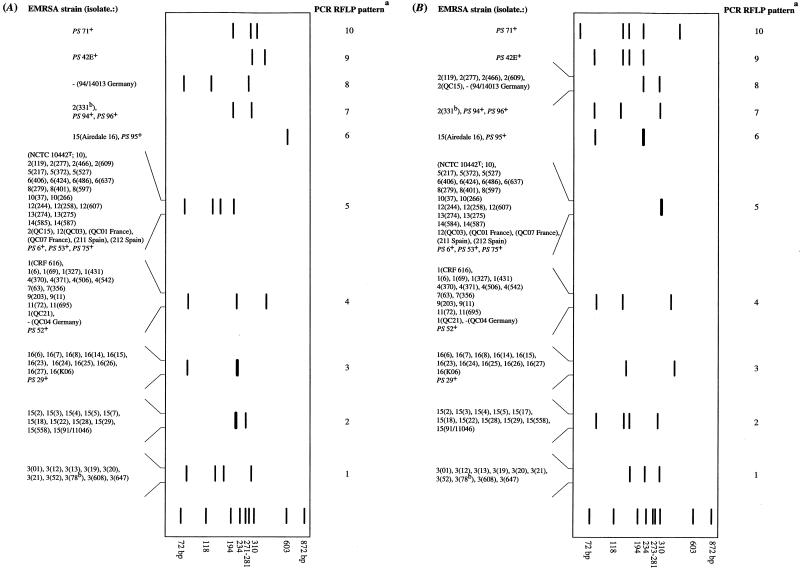

FIG. 3.

Unrooted consensus Jukes and Cantor (22) one-parameter and Fitch and Margoliash (14) distance tree showing the lineages of strains of S. aureus. a, unless otherwise stated, the RFLP pattern numbers were the same for both AluI and CfoI; b, GenBank accession numbers: the accession number for S. aureus 213 was X16457 (23) and that for S. aureus 8325-4 was X17679 (30); c, assigned to phylogenetic group; +, methicillin-sensitive S. aureus propagating strains (PS) used for international phage set; T, type strain (20) obtained from the National Collection of Type Cultures. The bootstrap values are the percentages of times that a taxon at that node occurred. The scale bar represents 0.1 substitution per sequence position (Knuc).

RESULTS

Size variation in the 3′ region of the coagulase gene.

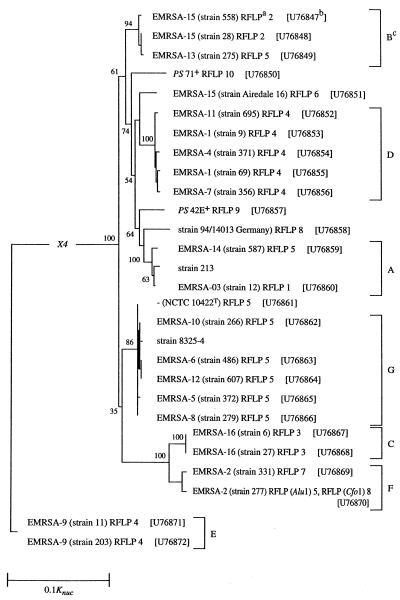

With the exception of the coagulase-negative strains, S. epidermidis NCTC 11047, S. haemolyticus NCTC 11042, and S. saprophyticus NCTC 7292, all strains examined produced a PCR amplicon. The four PCR products obtained were either 875 (±10 bp, n = 2), 660 (±20 bp, n = 10), 603 (±20 bp, n = 10), or 547 (±15 bp, n = 10) bp. All EMRSA-16 isolates gave a 547-bp product (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR-amplified coagulase genes from representatives of S. aureus. (A) Uncut PCR-amplified coagulase gene. Lanes 1 and 6, φX174 restriction fragment DNA/HaeIII marker; lane 2, PS 71; lane 3, EMRSA-15 isolate 2; lane 4, NCTC 10442T (20); lane 5, EMRSA-16 isolate 6. (B) PCR-amplified coagulase gene digested with the DNA restriction endonuclease AluI. Lanes 1, 6, 11, and 14, φX174 restriction fragment DNA/HaeIII marker; lanes 2, 3, 4, and 5, RFLP patterns 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively; lanes 7, 8, 9, and 10, RFLP patterns 5, 6, 7, and 8, respectively; lanes 12 and 13, RFLP patterns 9 and 10 (Fig. 2B). (C) PCR-amplified coagulase gene digested with CfoI. Lanes 1, 6, 11, and 14, φX174 restriction fragment DNA/HaeIII marker; lanes 2, 3, 4, and 5, RFLP patterns 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively; lanes 7, 8, 9, and 10, RFLP patterns 5, 6, 7, and 8, respectively; lanes 12 and 13, RFLP patterns 9 and 10, respectively (Fig. 2B).

PCR RFLP patterns of the coagulase gene.

PCR products were digested with AluI or CfoI, and the resulting fragments were separated (Fig. 1 and 2). No changes were observed in the sizes of the coagulase gene PCR products after repeated strain subcultivation (seven times) and DNA extraction. The mean values (standard errors of the means) from within-gel errors (n = 3) for duplicated strains were ± 10 bp for those fragments formed on AluI or CfoI digestion (Fig. 2).

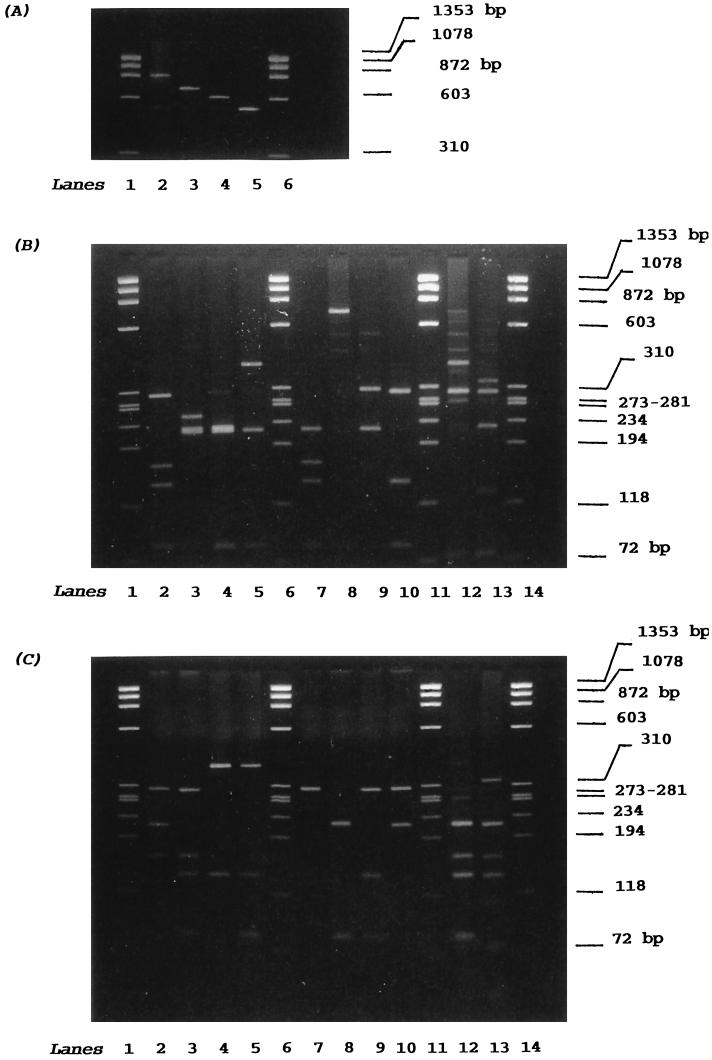

FIG. 2.

Schematic representations of PCR-amplified coagulase gene from S. aureus. (A) PCR-amplified coagulase gene digested with AluI. a, PCR RFLP pattern number; b, duplicate strains prepared on different occasions; +, methicillin-sensitive S. aureus propagating strains (PS) used for the international set of phages; T, type strain (20) obtained from the National Collection of Type Cultures, Central Public Health Laboratory, London, United Kingdom. The darker, thicker bands represent doublets. The schematic was prepared with Adobe Photoshop. (B) PCR-amplified coagulase gene digested with CfoI. a, PCR RFLP pattern number; b, duplicate strains prepared on different occasions; +, methicillin-sensitive S. aureus propagating (PS) strains used for the international set of phages; T, type strain (20) obtained from the National Collection of Type Cultures. The darker, thicker bands represent doublets.

Ten distinct RFLP patterns were observed among the 95 strains examined on AluI (Fig. 2A) and CfoI (Fig. 2B) digestion. Other enzymes specific for AT-rich DNA, such as HinfI and SacI, were less discriminatory (data not shown). The number of fragments produced upon AluI digestion varied from one (RFLP pattern 6) to four, and their sizes varied from 80 to 660 bp (Fig. 2A). Isolates Airedale 16 and PS 95 were not digested with AluI (RFLP pattern 6 [Fig. 2A]). The number of CfoI fragments varied from two (a doublet appears for RFLP pattern 5) to five, and their sizes varied from 60 to 400 bp (Fig. 1 and 2B). The assignments of isolates to one of the 10 AluI and CfoI RFLP patterns were similar, except for five isolates of EMRSA-2 (cf. Fig. 2A and B). These five isolates were characterized as belonging to RFLP pattern 5 on AluI digestion, and yet they fell into RFLP pattern 8 when digested with CfoI (Fig. 2B). The German isolate 94/14013 was also found in RFLP pattern 8 (cf. Fig. 2A and B). RFLP patterns 1, 2, and 3 corresponded to strains of EMRSA-3, EMRSA-15, and EMRSA-16, respectively (Fig. 2). RFLP patterns 4 and 5 encompassed a collection of isolates belonging to heterogeneous EMRSA strains (Table 1), and they accounted for approximately 50% of the isolates examined. They included five epidemic isolates from France, Spain, and Germany and four propagating strains (PS) used in the international phage set. RFLP pattern 4 was given by EMRSA-1, -4, -7, -9, and -11; the German isolate QC04; and PS 52. RFLP pattern 5 was characteristic of the type strain NCTC 10442; EMRSA-2, -5, -6, -8, -10, -12, -13, and -14; the French and Spanish isolates; and PS 6, PS 53, and PS 75 (Fig. 2). RFLP pattern 6 was given by the isolate Airedale 16 and PS 95. RFLP pattern 7 encompassed EMRSA-2 isolate 331, PS 95, and PS 96. Eight methicillin-sensitive propagating strains (PS) shared five patterns (RFLP patterns 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7) with methicillin-resistant strains. Representatives of lytic groups III (34) (PS 42E) and II (34) (PS 71) gave unique RFLP patterns 9 and 10, respectively.

Comparison of coagulase gene sequences.

The 3′ variable regions of the coagulase gene were sequenced for 26 isolates representing the 16 United Kingdom EMRSA strains and each of the 10 PCR RFLP patterns. Sequences were aligned, and pairwise distance measurements, based on 530 nucleotides for each strain, were used in the construction of a consensus phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3).

The same sequence similarities (percent S value) were obtained for two pairs of strains, EMRSA-16 isolates 6 and 27 and EMRSA-6 isolate 486 and EMRSA-12 isolate 607. Two major phylogenetic clusters were found. An outlier group was formed by two isolates (11 and 203) of EMRSA-9. The isolates 11 and 203 had 99.3% sequence similarity and were distantly related (nucleotide substitution rate of 1.1421 [Knuc]) to other isolates examined (Fig. 3). On this analysis, a larger cluster comprising 26 isolates was defined at and above 76.7% S and was bounded by EMRSA-15 isolate 558 and EMRSA-2 isolate 277. This cluster was subdivided into six groups (A, B, C, D, F, and G [Fig. 3]). Phylogenetic group B representing RFLP patterns 2 and 5, composed of EMRSA-15 isolates 558 and 28 and EMRSA-13 isolate 275, had sequence similarities between the isolates of 95.3% S. Strain PS 71 (lytic group II) (34) and the Airedale 16 isolate were distinct from each other (88.2% S) and from the isolate of group D (Fig. 3). Five representatives of RFLP pattern 4 formed a closely related group (D) at 98.9% S. PS 42E and the German isolate 94/14013 were separated from each other and from neighboring group A strains. Isolate 213, EMRSA-3 isolate 12, and EMRSA-14 isolate 587 had sequence similarities of 98.2% S and 88.6% S, respectively. Most isolates comprising RFLP pattern 5 formed a group, G, that was related at and above the 97.5% S level. EMRSA-8 isolate 279 had sequence similarity identical to that of NCTC 10442. EMRSA-16 isolates 6 and 27 (RFLP pattern 3) and EMRSA-2 isolates 331 and 277 were contained within groups C and F, respectively (Fig. 3). There was good congruence between the coagulase RFLP patterns and phylogenetic groupings (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

RFLP pattern and phylogenetic group of strains of EMRSA

| RFLP patterna | Phylogenetic groupb | Strain(s) of EMRSA |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | 3 |

| 2 | B | 15 |

| 3 | C | 16 |

| 4 | D | 1, 4, 7, 11 |

| 4 | E | 9 |

| 5 | A | 14 |

| 5 | B | 13 |

| 5 | F | 2 |

| 8c | F | 2 |

| 5 | G | 5, 6, 8, 10 |

Unless otherwise stated, PCR RFLP (AluI and CfoI).

Phylogenetic group assigned on the basis of coagulase gene sequence comparisons.

Pattern formed on CfoI.

DISCUSSION

The object of this study was to determine whether PCR RFLP patterns of the coagulase gene could be used to differentiate the major epidemic United Kingdom strains of MRSA. The coagulase genes from 95 isolates, representing predominant United Kingdom EMRSA strains, the Jevons MRSA strain, and propagating strains (PS), were amplified by PCR, and the products were digested with both AluI and CfoI. In this study, the parallel use of two DNA restriction endonucleases to digest the coagulase gene was beneficial in confirming the 10 distinct RFLP patterns among S. aureus strains. In addition, PCR CfoI RFLP pattern analysis allowed the differentiation of five EMRSA-2 isolates (Fig. 2B, RFLP pattern 8); this was not possible with AluI.

Other authors have used PCR RFLP pattern analysis to study S. aureus, but only Tenover et al. (39) phage typed any of the strains. Furthermore, reference strains were not used, and differing PCR primers were employed (15, 25, 26, 29, 38, 39). It is therefore not possible to compare the results of this study with those of previous coagulase PCR RFLP pattern analyses.

The RFLP patterns 1, 2, and 3 were simple (three to four bands) and unique and allowed the typing of the important United Kingdom epidemic strains, EMRSA-3, EMRSA-15, and EMRSA-16 (Fig. 2). These EMRSA strains also clustered within the phylogenetically distinct groups A, B, and C, respectively (Table 2) (Fig. 3). In the light of coagulase PCR RFLP and sequence comparisons, most isolates with RFLP patterns 4 and 5 gave distinct groups D and G, respectively (Table 2) (Fig. 2 and 3). Isolates of EMRSA-2 were exceptional, in that they formed a single phylogenetic group (F) and yet gave two RFLP patterns, 5 and 8 (Table 2).

Isolates of MRSA from France (QC01 and QC07) and Spain (211 and 212) have given similar patterns on ribotyping, PFGE (2, 34), and coagulase typing (this study) and are thought to be representative of an epidemic clone circulating within Europe. In contrast, the German isolate 94/14013 was distinct and clearly separable from the other European isolates studied (2, 41) (Fig. 2 and 3).

The propagating strains, PS 42E and PS 71, represent some of the diverse types of isolates from human clinical material. They can be differentiated by ribotype (34) and by their unique coagulase RFLP patterns, 9 and 10, respectively (Fig. 2).

Isolate Airedale 16 has phage type EMRSA-15, and yet unlike other EMRSA-15 strains, it does not produce enterotoxin C, has a unique PCR RFLP pattern, and is atypical on PFGE (31). It is a sporadic outbreak strain which may have originated from horizontal genetic transfer of resistance genes from MRSA to methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (cf. reference 36). It is evident from the populations studied so far that antibiotic-sensitive strains exhibited greater genetic diversity than did resistant strains (reference 7 and this study).

This study demonstrates the value of PCR RFLP (AluI and CfoI) pattern analysis of the coagulase gene for the rapid initial genotyping of S. aureus, particularly of the major United Kingdom epidemic strains, EMRSA-3, EMRSA-15, and EMRSA-16. The RFLP patterns observed in this study were substantiated by the analysis of sequence data in that the patterns gave rise to parallel phylogenetic groups.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Philip P. Mortimer, Jonathan P. Clewley, and John Stanley for critical reading of the manuscript and to Jon White for artwork.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anonymous. Epidemic methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Commun Dis Rep. 1996;6:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aparicio P, Richardson J, Martin S, Vindel A, Marples R R, Cookson B D. An epidemic methicillin-resistant strain of Staphylococcus aureus in Spain. Epidemiol Infect. 1992;108:287–298. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800049761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asheshov E H, Skalova R. International Committee on Systematic Bacteriology. Subcommittee on the Phage-Typing of Staphylococci. Minutes of the meeting, 26 September 1974. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1975;25:233–234. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bannerman T L, Hancock G A, Tenover F C, Miller J M. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis as a replacement for bacteriophage typing of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:551–555. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.551-555.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blair J E, Williams R E O. Phage typing of staphylococci. Bull W H O. 1961;24:771–784. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrne M E, Littlejohn T G, Skurray R A. Transposons and insertion sequences in the evolution of multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus. In: Novick R P, editor. Molecular biology of the staphylococci. New York, N.Y: VCH Publishers; 1990. pp. 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carles-Nurit M J, Christophle B, Broche S, Gouby A, Bouziges N, Ramuz M. DNA polymorphisms in methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2092–2096. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.8.2092-2096.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cookson B, Talsania H, Naidoo J, Phillips I. Strategies for typing and properties of epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1986;5:702–709. doi: 10.1007/BF02013309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cookson B D, Aparicio P, Deplano A, Struelens M, Goering R, Marples R. Inter-centre comparison of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for the typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Med Microbiol. 1996;44:179–184. doi: 10.1099/00222615-44-3-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corpet F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cowan S T. Characterization tests. In: Cowan S T, editor. Cowan and Steel’s manual for the identification of medical bacteria. 2nd ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1974. pp. 166–180. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox R A, Conquest C, Mallaghan C, Marples R R. A major outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus caused by a new phage-type (EMRSA-16) J Hosp Infect. 1995;29:87–106. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(95)90191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuny C, Claus H, Witte W. Discrimination of S. aureus by PCR for r-RNA gene spacer size polymorphism and comparison to SmaI macrorestriction patterns. Zentralbl Bakteriol. 1996;283:466–476. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(96)80123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitch W M, Margoliash E. Construction of phylogenetic trees. A method based on mutation distances as estimated from cytochrome c sequences is of general applicability. Science. 1967;155:279–284. doi: 10.1126/science.155.3760.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goh S-H, Byrne E E, Zhang J L, Chow A W. Molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus on the basis of coagulase gene polymorphisms. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1642–1645. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1642-1645.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grubb W B. Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant S. aureus. In: Novick R, editor. Molecular biology of the staphylococci. New York, N.Y: VHC Publishers; 1990. pp. 595–606. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurtler V, Barrie H D. Typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains by PCR-amplification of variable-length 16S-23S rDNA spacer regions: characterization of spacer sequences. Microbiology. 1995;141:1255–1265. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-5-1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartstein A I, Morthland V H, Eng S, Archer G L, Schoenknecht F D, Rasad A L. Restriction enzyme analysis of plasmid DNA and bacteriophage typing of paired Staphylococcus aureus blood culture isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1874–1879. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.8.1874-1879.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarlov J O, Rosdahl V T, Yeo M, Marples R R. Lectin-typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from Singapore, England & Wales, and Denmark. J Med Microbiol. 1993;39:305–309. doi: 10.1099/00222615-39-4-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jevons M P. “Celbenin”-resistant staphylococci. Br Med J. 1961;1:124–125. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones A S. The isolation of bacterial nucleic acids using cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CETAVLON) Biochim Biophys Acta. 1953;40:273–286. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(53)90304-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jukes T H, Cantor C R. Evolution of protein molecules. In: Munro H N, editor. Mammalian protein metabolism. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 21–132. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaida S, Miyata T, Yoshizawa Y, Igarashi H, Iwanage S. Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence of staphylocoagulase gene from Staphylococcus aureus strain 213. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:8871. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.21.8871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kloos W E, Schleifer K H. Family I. Micrococcaceae. Genus IV. Staphylococcus, Rosenbach 1884, 18AL. In: Sneath P H A, Mair N S, Sharpe M E, Holt J G, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 2. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1986. pp. 1013–1035. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi N, Tanguchi K, Kojima K, Urasawa S, Uehara N, Omizu Y, Yagihashi A, Kurokawa I. Analysis of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus by a molecular typing method based on coagulase gene polymorphism. Epidemiol Infect. 1995;115:419–426. doi: 10.1017/s095026880005857x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawrence C, Cosseron M, Mimoz O, Brun-Buisson C, Costa Y, Sammii K, Duval J, Leclercq R. Use of the coagulase gene typing method for the detection of carriers of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:687–696. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marples R R, Cooke E M. Current problems with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Hosp Infect. 1988;11:381–392. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(88)90093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulligan M E, Kwok R Y, Citron D M, John J J, Smith P B. Immunoblots, antimicrobial resistance, and bacteriophage typing of oxicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:2395–2401. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.11.2395-2401.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nada T, Ichiyama S, Osada Y, Ohta M, Shimokata K, Kato N, Nakashima N. Comparison of DNA fingerprinting by PFGE and PCR-RFLP of the coagulase gene to distinguish MRSA isolates. J Hosp Infect. 1996;32:305–317. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(96)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phonimdaeng P, O’Reilly M, Nowlan P, Bramley A, Foster N. The coagulase of Staphylococcus aureus 8325-4: sequence analysis and virulence of site-specific coagulase-deficient mutants. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:393–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richardson J F, Reith S. Characterization of a strain of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (EMRSA-15) by conventional and molecular methods. J Hosp Infect. 1993;25:45–52. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(93)90007-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richardson J F, Chittasobhon N, Marples R R. A supplementary phage set for the investigation of methicillin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus. J Med Microbiol. 1988;25:67–74. doi: 10.1099/00222615-25-1-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richardson J F, Quoraishi A H M, Francis B J, Marples R R. Beta-lactamase negative, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a newborn nursery: report of an outbreak and laboratory investigations. J Hosp Infect. 1990;16:109–121. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(90)90055-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson J F, Aparicio P, Marples R R, Cookson B D. Ribotyping of Staphylococcus aureus: an assessment using well defined strains. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;112:93–101. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800057459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbour joining method: a new method for constructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider C, Weindel M, Brade V. Frequency, clonal heterogeneity and antibiotic resistance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolated in 1992–1994. Zentralbl Bakteriol. 1996;283:529–542. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(96)80131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schumacher-Perdreau F, Jansen B, Seifert H, Peters G, Pulverer G. Outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a teaching hospital: epidemiological and microbiological surveillance. Zentralbl Bakteriol. 1994;280:550–559. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80516-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwarzkopf A, Karch H. Genetic variation in Staphylococcus aureus coagulase genes: potential and limits for use as an epidemiological marker. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2407–2412. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2407-2412.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tenover F C, Arbeit R, Archer G, Biddle J, Byrne S, Goering R, Hancock G, Hébert G A, Hill B, Hollis R, Jarvis W R, Kreiswirth B, Eisner W, Maslow J, McDougal L K, Miller J M, Mulligan M, Pfaller M A. Comparison of traditional and molecular methods of typing isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:407–415. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.2.407-415.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomson-Carter F M, Carter P E, Purcell T M, Pennington T H. Application of genotypic techniques in analyses of staphylococcal infections. In: Wadstrom T, Holder I A, editors. Molecular pathogenesis of surgical infections. Stuttgart, Germany: Gustav Fischer Verlag; 1994. pp. 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Witte W, Cuny C, Braulke C, Hueck D. Clonal dissemination of two MRSA strains in Germany. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;113:67–73. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800051475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhen L, Swank R T. A simple and high yield method for recovering DNA from agarose gels. BioTechniques. 1993;14:894–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]