Abstract

Background

Determining the potential barriers responsible for delaying access to care, and elucidating pathways to early intervention should be a priority, especially in Arab countries where mental health resources are limited. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the relationship between religiosity, stigma and help-seeking in an Arab Muslim cultural background. Hence, we propose in the present study to test the moderating role of stigma toward mental illness in the relationship between religiosity and help-seeking attitudes among Muslim community people living in different Arab countries.

Method

The current survey is part of a large-scale multinational collaborative project (StIgma of Mental Problems in Arab CounTries [The IMPACT Project]). We carried-out a web-based cross-sectional, and multi-country study between June and November 2021. The final sample comprised 9782 Arab Muslim participants (mean age 29.67 ± 10.80 years, 77.1% females).

Results

Bivariate analyses showed that less stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness and higher religiosity levels were significantly associated with more favorable help-seeking attitudes. Moderation analyses revealed that the interaction religiosity by mental illness stigma was significantly associated with help-seeking attitudes (Beta = .005; p < .001); at low and moderate levels of stigma, higher religiosity was significantly associated with more favorable help-seeking attitudes.

Conclusion

Our findings preliminarily suggest that mental illness stigma is a modifiable individual factor that seems to strengthen the direct positive effect of religiosity on help-seeking attitudes. This provides potential insights on possible anti-stigma interventions that might help overcome reluctance to counseling in highly religious Arab Muslim communities.

Keywords: Stigma, Help-seeking attitudes, Mental illness, Religiosity, Islam, Arab countries

Introduction

Religiosity is an integral part of most humans' daily lives [1]; particularly in Arab countries (e.g. [2–4],) where Muslims comprise more than 95 percent of the populations [5]. Religiosity may be defined as the set of individuals’ attitudes, behaviors and commitment reflecting respect of higher nonhuman power [6]. Religious beliefs shape the way people view and manage their mental health and illness [7, 8]. This view is originated in the Health Belief Model [9], that counts religion as one of the main variables affecting the way people manage their health and illness in general. Hamdan [10] argue that it is important to consider religious beliefs in relation to mental illness, particularly within Arab societies due to the power of religion (Mostly Islam) within the region over populations. Ng et al. [11] found that individuals who affiliated themselves with a religion (Christianity, Islam, Buddhism/Taoism, and Hinduism) were less likely to seek treatment. They argue that these results reflect beliefs and stigma surrounding mental illness.

Many Arab countries, such as Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Palestine, Syria, and Yemen, have been experiencing years of wars, armed conflict, and political unrest. The outcomes of these conflicts are expected to result in higher rates of mental health problems, and impairment in the mental health services and programs [12]. The Islamic teachings, which are dominant in most Arab countries, mandate Muslims to seek treatment when they get sick. Unfortunately, Gearing et al. [13] reported that the stigma attached to mental illness is one of the key factors that negatively influences Arab patients with mental illness accessing psychiatric services, contributing to the underutilization of mental health care.

The World Health Organization [14] defines stigma as “a mark of shame, disgrace or disapproval which results in an individual being rejected, discriminated against, and excluded from participating in a number of different areas of society”. The tendency to stigmatize appears to be a profoundly rooted attitude in human nature as a way of responding to people who seem or perform differently. Stigmatization is thereby based on the fear that those who seem different may behave in threatening or unpredictable ways [15]. Religious beliefs have been shown to significantly impact individuals’ attitudes toward mental disorders, however in diverse ways [16]. A systematic review has, for example, reported mixed findings with respect to the relationship between religiosity and stigma in Black Americans [17]. Most of the evidence on the association between religiosity and mental health stigma has emerged from Western countries (Europe and USA) [18–22], while only a very few studies have been performed in Arab countries. For instance, a Jordanian study published in 2021 found that higher levels of religiosity significantly correlated with lower mental health stigma among students in secondary school, but this correlation was no longer significant when adjusting for other sociodemographic variables [23]. Religiosity has also been found to significantly correlate with more positive attitudes toward people with mental illnesses in Muslim Jordanian students [24]. It is widely common in Arab Muslim culture to believe that mental illness is caused by lack of faith [25]. A study found that a large proportion of Qatari Muslim university students agreed that “mental illness is a punishment from God", which was reflected in their high endorsement of stigmatizing attitudes toward people with mental illness [26]. Another study found that 67.3% the of people from the Saudi general population believed that depression was caused by lack of faith and 56% believed in faith healers as an appropriate treatment approach [27]. Additionally, in a study on perceptions of and attitudes toward mental illness among both medical students and the general public in Oman, Al-Adawi et al. [28] found that groups believed that mental illness is caused by spirits and rejected genetics as a significant factor. As in Saudi Arabia, the social stigma surrounding mental issues appears to be profound, and to directly affect help-seeking behavior [29]. On the other hand, there is sufficient evidence that Arab people tend to hold negative attitudes toward professional help-seeking [30–37], and rather tend to rely on informal sources of help rather than seeking mental health care service [38–40]. Indeed, both Arabs living in Arab countries (e.g. [41–44],) and Arab immigrant minorities living in Western countries (e.g. [45–47],) have been found to highly endorse supernatural/religious causal attributions, and thereby tend to prefer seeking help from traditional healers and religious authorities when experiencing mental health problems. In Arab Muslim societies, mental illness is framed and explained through religious beliefs [10]. These beliefs include Punishment from God, a test from God, Jinn, Evil eye, satanic power and more [10, 44]. For instance, Bener and Ghuloum [48] found that almost half of the participants from the general Qatari population, believed that mental illness is a punishment from God, and almost 40% of respondents from believed that people with mental health disorders are “mentally retarded”. A recent systematic literature review identified mental Illness conceptualization, stigma, traditional healing methods, and religious leaders as amongst the major reasons for negative help-seeking attitudes and reluctance to engage in counselling among citizens of the Arab region [36]. A study conducted in Baghdad revealed that 83% of the participants believe that mental illnesses need medical management while 17% trust in traditional methods (religion and faith healers) [49]. Therefore, help-seeking attitudes, intentions and behaviors appear to be multi-determined in nature [50]; and there seems to be a complex interplay between religiosity, stigma, and help-seeking.

Many studies have addressed mental health stigma and its impact on help seeking behaviors. Some of these studies were conducted in the Arab region (e.g. [31, 37, 51, 52],) where religion was mentioned as a major contributing factor in shaping perceptions and social attitudes towards mental illness. In 2001, the WHO identified mental health stigma as a key barrier to effective treatment of mental illness due to its negative impact on individuals’ willingness to seek treatment. In their systematic review of 144 studies and 90189 participants, Clement et al. [53] reported that the median association between stigma and help-seeking was d = − 0.27, with internalized and treatment stigma being most often associated with reduced help-seeking. They also reported that mental health stigma was the fourth highest ranked barrier to help-seeking [53]. Similarly, other systematic reviews and meta-analyses findings revealed that individuals’ own stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness (or perceived public stigma) were associated with a significant 0.82-fold decrease in active help-seeking [54]; albeit anti-stigma interventions showed no effectiveness in improving formal help-seeking behaviors in the general public [55]. This suggests that variables other than stigma should be taken into account when assessing factors driving help-seeking in the community.

To date, scarce studies have focused on factors related to help-seeking in low- and middle-income countries [55], with the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region as no exception. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the relationship between religiosity, stigma and help-seeking in an Arab Muslim cultural background. Choosing religious and traditional healers as first care providers over health care professionals may lead to substantial delays in accessing formal mental health services [56]. Thus, determining the potential barriers responsible for delaying access to care, and elucidating pathways to early intervention should be a priority, especially in Arab countries where mental health resources are limited [57]. Hence, we propose in the present study to test the moderating role of stigma toward mental illness in the relationship between religiosity and help-seeking attitudes among Muslim community people living in different Arab countries.

Methods

Sample and procedure

The current survey was part of a large-scale multinational collaboration project (StIgma of Mental Problems in Arab CounTries [The IMPACT Project]) [58]; aimed at providing a cross-cultural examination of stigma towards patients with mental illness across the Arab countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. We carried-out a web-based cross-sectional, and multi-country study between June and November 2021 (Further details about the project have been reported elsewhere [44]). Eligible participants were community individuals aged over 18 years, Arabic-speaking and Muslim. Data collection in all countries was performed using an anonymous online questionnaire (in the Arabic language) and convenience sampling. Invitations to participate in the study were sent through social media platforms and acquaintances; after that, we used the snowball sampling technique (each subject provided multiple referrals) to recruit the rest of the sample. No credits were awarded for participating.

Initially, 10036 valid responses have been received. A total of 254 participants were excluded because of their religious affiliation (Christianity 48.0%, Atheism 41.3%, Judaism 2,8%, other religions 7.9%). The final sample comprised 9782 Arab Muslim participants originating from and residing in 16 Arab countries. The distribution of participants across countries was as follows: Algeria: N = 150; Egypt: N = 1029; Jordan: N = 426; Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: N = 872; Kuwait: N = 2182; Lebanon: N = 781; Libya: N = 108; Mauritania: N = 396; Morocco: N = 328; Oman: N = 78; Palestine: N = 448; Qatar: N = 130; Sudan: N = 102; Tunisia: N = 2343; United Arab Emirates: N = 150; and Yemen: N = 259.

As for ethical considerations, the study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki for human research, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the home institution of the Principal Investigator, FFR (Razi Psychiatric Hospital, Tunisia) [Reference number is 2021–0034]. All participants provided their online informed consent to participate before beginning the survey. No compensation was offered.

Measures

We collected the following sociodemographic data for all participants: age, gender, marital status (married vs. unmarried [single, divorced/separated, widowed]), education level (primary, secondary, tertiary), self-perceived socioeconomic status (high, average, low), residency (urban, rural), as well as family and personal psychiatric history (any mental illness diagnosed by a professional; yes/no). Information on mental health stigma, religiosity and help-seeking attitudes was collected using the Arabic versions of the following measurement instruments:

The community attitudes toward the mentally ill scale (CAMI) [59, 60]

The CAMI is a measure evaluating public attitudes towards people with mental illness through forty items and four subscales: Social Restrictiveness (e.g., “The mentally ill should not be given any responsibility), Benevolence (e.g., The mentally ill have for too long been the subject of ridicule”), Authoritarianism (e.g., “One of the main causes of mental illness is a lack of self-discipline and will power”), and Community Mental Health Ideology (e.g., “As far as possible, mental health services should be provided through community based facilities”). Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). Lower total scores indicate more stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness. The Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale in the present study was of 0.875.

The attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help scale-short form (ATSPPH-SF) [30, 61]

The ATSPPH-SF is a 10-item four-point Likert scale (e.g., “If I believed I was having a mental breakdown, my first inclination would be to get professional attention”; “I would want to get psychological help if I were worried or upset for a long period of time”). Total scores range from 0 to 40, with higher total scores referring to greater positive attitudes toward help-seeking (Please refer to [44] for further details about means and standard deviations of stigma [CAMI] and help-seeking attitudes [ATSPPH-SF] by country). In the current study, the Cronbach's alpha value was of 0.69, indicating an acceptable overall internal consistency.

The Arabic religiosity scale (ARS) [62]

The ARS is a five-item measure that assesses participants’ religiosity levels in three dimensions: (1) Behavioral religiosity (private and public) (e.g., “Do you have individual religious activities (individual prayers)?”), (2) Cognitive/affective importance of religiosity (both at lifetime and at time of difficulties) (e.g., “What is the importance of religious beliefs in the full curriculum of your life?”), and (3) General self-rate level of belief (e.g., “How do you evaluate the degree of your faith?”). Example of items: Answers to each item vary from 1 (never, absent, not important) to 4 (always, most times, great importance). Only total scores have been considered in the present study, with higher scores indicating greater levels of religiosity. The present sample revealed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70 for the ARS total score.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS software v.25 was used for the statistical analysis. The CAMI, ATSPPH-SF, and ARS scores were considered normally distributed since the skewness and kurtosis values varied between -2 and + 2. The Student t was used to compare two means and the Pearson test was used to correlate two continuous variables. The moderation analysis was conducted using PROCESS MACRO v3.4, model 1 taking religiosity as the independent variable, stigma as the moderator and help-seeking attitudes as the dependent variable. Results were adjusted over variables that showed a p < 0.25 in the bivariate analysis. P < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

Sociodemographic and other characteristics of the sample

A total of 9782 were involved in this study, with a mean age of 29.67 ± 10.80 years and 77.1% females. Other descriptive statistics of the sample can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and other characteristics of the sample (N = 9782)

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 2236 (22.9%) |

| Female | 7546 (77.1%) |

| Marital status | |

| Unmarried | 5719 (58.5%) |

| Married | 4063 (41.5%) |

| Education level | |

| Secondary or less | 1032 (10.5%) |

| Tertiary | 8750 (89.5%) |

| Self-perceived socioeconomic status | |

| High | 2390 (24.4%) |

| Average | 6761 (69.1%) |

| Low | 631 (6.5%) |

| Residency | |

| Urban | 8378 (85.6%) |

| Rural | 1404 (14.4%) |

| Personal psychiatric history | |

| No | 8806 (90.0%) |

| Yes | 976 (10.0%) |

| Personal medical history | |

| No | 8856 (90.5%) |

| Yes | 926 (9.5%) |

| Mean ± SD | |

| Age (years) | 29.67 ± 10.80 |

| CAMI score | 133.59 ± 17.64 |

| Help-seeking attitudes | 21.80 ± 6.02 |

| Religiosity | 15.28 ± 2.66 |

Bivariate analysis of factors associated with help-seeking attitudes

The results of the bivariate analysis of factors associated with help-seeking attitudes are summarized in Table 2. The results showed that a higher mean help-seeking attitudes score was found in females, participants with a university level of education, with a good socioeconomic status, with a personal psychiatric or medical history. Higher CAMI and religiosity scores were significantly associated with higher help-seeking attitudes scores.

Table 2.

Bivariate analysis of factors associated with help-seeking attitudes (ATSPPH-SF total scores)

| Variable | Categorical variables | |

|---|---|---|

| mean ± SD | p | |

| Sex | < .001 | |

| Male | 21.31 ± 6.25 | |

| Female | 21.95 ± 5.94 | |

| Marital status | .067 | |

| Single | 21.89 ± 6.26 | |

| Married | 21.67 ± 5.66 | |

| Education level | .003 | |

| Secondary or less | 21.27 ± 6.04 | |

| University | 21.86 ± 6.01 | |

| Socioeconomic status | < .001 | |

| Good | 22.08 ± 6.55 | |

| Average | 21.80 ± 5.79 | |

| Bad | 20.73 ± 6.20 | |

| Region of living | .631 | |

| Urban | 21.79 ± 5.93 | |

| Rural | 21.88 ± 6.53 | |

| Personal psychiatric history | < .001 | |

| No | 21.70 ± 5.98 | |

| Yes | 22.74 ± 6.29 | |

| Personal medical history | .004 | |

| No | 21.86 ± 5.99 | |

| Yes | 21.23 ± 6.26 | |

| Continuous variables | ||

| r | p | |

| Age | -.003 | .737 |

| CAMI | .27 | < .001 |

| Religiosity | .07 | < .001 |

CAMI Community Attitudes toward the Mentally Ill scale, ATSPPH-SF Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale-Short Form

Moderation analysis with help-seeking attitudes scores taken as the dependent variable

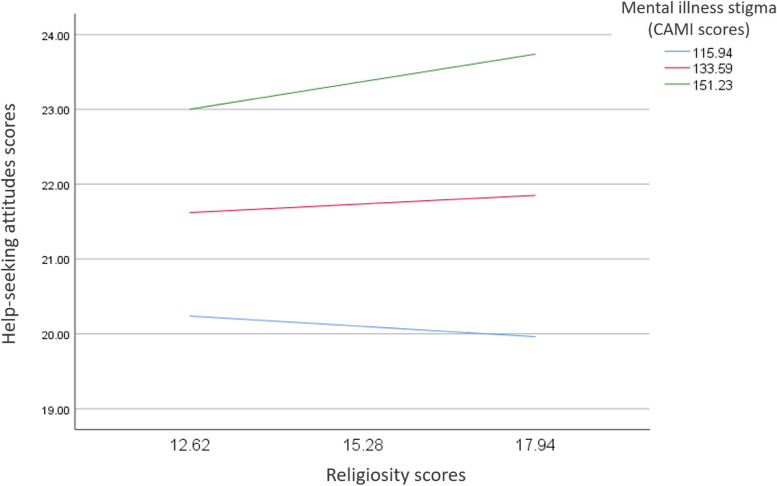

The details of the moderation analysis are summarized in Tables 3 and 4 and Fig. 1. The interaction religiosity by CAMI was significantly associated with help-seeking attitudes (Beta = 0.005; p < 0.001); at high levels of CAMI, higher religiosity (Beta = 0.14, p < 0.001) as significantly associated with more favorable help-seeking attitudes.

Table 3.

Moderation analysis taking religiosity as the independent variable, stigma (CAMI total scores) as the moderator and help-seeking attitudes as the dependent variable

| Moderator | Beta | t | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religiosity | -.68 | -4.07 | < .001 | -1.00; -.35 |

| CAMI | .01 | .53 | .594 | -.03; .05 |

| Interaction religiosity by CAMI | .005 | 4.28 | < .001 | .003; .008 |

Results adjusted over gender, marital status, education level, personal history of medical illness, personal history of psychiatric illness, and socioeconomic status. CAMI Community Attitudes toward the Mentally Ill scale

Table 4.

Conditional effects of the focal factors at values of CAMI as the moderator

| Beta | t | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 115.94 | -.05 | -1.75 | .080 | -.11; .01 |

| 133.59 | .04 | 1.85 | .065 | -.003; .09 |

| 151.23 | .14 | 3.97 | < .001 | .07; .21 |

CAMI Community Attitudes toward the Mentally Ill scale

Fig. 1.

Graphical depiction of the association of the interaction religiosity by mental illness stigma and help-seeking attitudes. Low and high levels of mental illness stigma were plotted at -1 SD and + 1 SD respectively

It is noteworthy that the interactions community mental health ideology by religiosity (Beta = -0.001; t = -0.42; p = 0.674; 95% CI -0.01, 0.01), authoritarianism by religiosity (Beta = -0.007; t = -1.46; p = 0.145; 95% CI -0.02, 0.002), benevolence by religiosity (Beta = -0.007; t = -1.45; p = 0.148; 95% CI -0.02, 0.002) and social restrictiveness by religiosity (Beta = 0.002; t = 0.56; p = 0.578; 95% CI -0.01, 0.01) did not show a significant association with help-seeking attitudes.

Discussion

In this study we sought to provide, for the first time, an in-depth examination of the relationship between religiosity and help-seeking attitudes in Arab Muslim community people, by investigating the moderating effects of mental health stigma in this relationship. Findings revealed that higher religiosity levels were associated with greater positive attitudes towards seeking professional help. In addition, moderation analyses were significant, showing that the strength of the relationship between religiosity and help-seeking attitudes was strongly influenced by mental health stigma. We discuss the relevance and implications of these results later in this paper.

Regarding the direct effect, higher religiosity was significantly linked to more favorable attitudes toward seeking formal professional help. This further supports that religion “can act as such a dynamic social force”, and should be accounted for when studying human psychology, perception and behavior [16]. While some claim that religious people from Muslim countries rely on religious resources for treatment such as Quran reciting (e.g., [63]), our findings show that religiosity might be a factor for better perceiving help-seeking. Any comparisons with previous literature in Muslim communities are challenging, given that most of the previous studies in this area have investigated religious factors as causal attributions through qualitative methods or self-developed measures (e.g. [26, 64–68],), whereas no studies have used a valid measure to assess the religiosity construct specifically in relation to help-seeking. Besides, while a substantial amount of literature has consistently found that religiosity is protective against mental health problems [69], only dearth of research examined the relationship between religiosity and help-seeking [70]. Consistent with our findings, a study reported that higher levels of private, non-organizational religiosity were correlated with greater utilization of professional mental health services among American community older adults [71]. Another study suggested that this positive effect of religiosity on counseling could differ depending on individuals’ level of distress [72]. Furthermore, a recent Lebanese study [73] showed a positive correlation between higher levels of mature religiosity and higher engagement coping strategies but less disengagement strategies. This association might be explained by the belief that God is in control of the problem [74]; the individual feels more encouraged to face the problem or emotion because they believe that God can alter the situation for the better. It promotes engagement, like seeking-help, especially when there are high chances of achieving the established goals, and, to a lesser extent, disengagement, which is more likely to be adaptive, especially under adverse circumstances [75]. Contrarily, a large study among African American adults showed inverted patterns of associations between religiosity and service use [76]. In Islam, seeking treatment for mental health issues does not conflict with seeking help from God [77], which might explain our results. Beyond this direct effect, we explored the moderating role of mental illness stigma in the relation religiosity-help-seeking attitudes, which we discuss in the next section. Investigating moderators may help elucidate the nature of this relationship and provide explanations for the variations in results across studies.

Moderation refers to a situation in which a moderator changes either the strength or the direction of a relationship between two constructs; the relationship is thus not constant but depends on the values of the moderator variable [78]. As expected, we found that both mental health stigma had a significant moderating role in the path from religiosity to help-seeking attitudes. This means that the relationship between religiosity and help-seeking attitudes differs as a function of stigmatizing beliefs towards mental illness. More precisely, mental illness stigma has a pronounced negative effect on the religiosity to help-seeking attitudes relationship – the higher the stigma toward mental illness (lower CAMI score), the weaker the relationship between religiosity and help-seeking attitudes. Additionally, in lowly and moderately stigmatizing individuals, religiosity was positively associated with help-seeking attitudes, whereas for highly stigmatizing individuals, religiosity was negatively associated with help-seeking attitudes. This finding is consistent with previous literature stipulating that people who tend to exhibit lower levels of mental health stigma have more favorable attitudes toward professional help-seeking [54]. People that are more religious tend to more strongly perceive counseling as appropriate and effective when they display low stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness. These findings suggest that tackling stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness held by community individuals may help strengthen the positive effects of religiosity on help-seeking attitudes.

Limitations

Some limitations should be discussed. Because of the cross-sectional design, we could not conclude about causality, and longitudinal research is still needed to determine directionality in the associations between study variables. In addition, while we report on findings among Arab Muslims, we cannot catch the impact of culture and how this interacts with religiosity. For sorting this, a future study on Muslim communities in other regions (such as South Asia, Turkey, and Iran) can report the impact of culture on Muslim communities. Furthermore, removing other religions from the study at its beginning, might limit us from reporting on differences between different religions. For solving this, a future study among bugger sample of non-Muslim Arabs, can tell about the specific impact for religion, because they all affiliate to the same culture. In addition, although Arab populations live in the MENA share values, beliefs, and traditions [42, 79], there are some differences between the different three main regions (Middle East, North Africa and the Gulf States) that we did not report in this study because we focused on religion rather than culture. These differences might have influenced attitudes toward mental illness and help-seeking across countries [80]. Future research that focuses on culture supposed to highlight these differences, and how these differences shape mental health stigma and help seeking behaviors. Finally, our study did not assess the dimension of self-stigma, hence, it’s recommended to assess in future studies the four stigma types (help-seeking attitudes and personal, self and perceived public stigma) on active help-seeking in the general population.

Study implications

The present study revealed that total religiosity (involving behavioral, affective and general level of belief) is positively associated with favorable attitudes toward help-seeking in a large sample of Muslim people from different Arab countries. These findings may change our current approach to addressing reluctance towards help seeking and our perception that religiosity is regarded as a barrier to care access in Arab Muslim contexts, while it could act as a facilitator in certain circumstances. Longitudinal studies are necessary before drawing any firm conclusions. Interestingly, this study revealed that highly religiosity is associated with favorable attitudes toward seeking professional help in individuals who exhibited low to moderate levels of stigma toward mental illness. This finding suggest that mental illness stigma is a modifiable individual factor that seems to strengthen the direct positive effect of religiosity on help-seeking attitudes. This provides potential insights on possible anti-stigma interventions that might help overcome reluctance to counseling in highly religious Arab Muslim community individuals. Stigma is universal, occurring in every country and region of the world, albeit with different manifestations in different social and cultural contexts [81]. Given the uniqueness of the cultural Arab context, there is a strong need to design culturally- appropriate and sensitive interventions intended to reduce the occurrence and impact of stigma related to mental illness, in order to maximize their efficiency [82, 83]. At present, there is insufficient evidence on the types of intervention that may be effective and feasible in low- and middle-income countries [84]. A very few anti-stigma campaigns have previously been implemented in some Arab countries, such as the anti-stigma initiative launched by the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) in Morocco and Egypt [85]. Besides, there have been some initiatives to suggest avenues to reduce stigma and combat negative stereotype related to mental illness in the Middle East; such as a systematic literature by Sewilam et al. [42], which proposed some lines of intervention (educating family caregivers and young people in schools, increasing cooperation between medical professionals and traditional healers). A qualitative review of literature suggested that implementing mental health legislations and policies within the health-care setting might be effective in combatting stigma in Arab countries [38]. More efforts should be put on developing and implementing evidence‐informed population-based anti-stigma programs that are carefully tailored to the Arab Muslim cultural backgrounds. Finally, additional international and cross-cultural research is required to further elucidate the specific mechanisms (moderators and mediators) by which religiosity may contribute to positive or negative attitudes toward help-seeking.

Conclusion

Religion has a strong impact on Muslim communities, and religious beliefs can be major factors in shaping health perceptions and behaviors. To date, there has been scant or no research attention to the relationship between religiosity and help-seeking attention in Arab Muslim contexts. Despite a general agreement that religious factors are closely linked to negative mental help-seeking attitudes and reported avoidance of help-seeking, the present findings suggest for the first time the contrary. We also demonstrated that mental illness stigma is a modifiable individual factor that seems to strengthen the direct positive effect of religiosity on help-seeking attitudes. The lower the stigma toward mental illness, the stronger the relationship between religiosity and favorable help-seeking attitudes. These findings may help inform the development of culturally tailored anti-stigma interventions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants.

Authors’ contributions

FFR designed the study; MS, AA, MH, AHMS, CMFML, ER, JS, NS, MF, BZ, AYN, SO, MS, SH, LM, MPB, AHM, MB, AMB, NS, SA, and FG collected the data; FFR, SDN and SH drafted the manuscript; SH carried out the analysis and interpreted the results; NS, AAL, MPB, MB and MC reviewed the paper for intellectual content; all authors reviewed the final manuscript and gave their consent.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are not publicly available due the restrictions from the ethics committee. Reasonable requests can be addressed to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki for human research, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the home institution of the Principal Investigator, FFR (Razi Psychiatric Hospital, Tunisia) [Reference number is 2021–0034]. All participants provided their online informed consent to participate before beginning the survey. No compensation was offered. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Feten Fekih-Romdhane, Email: feten.fekih@gmail.com.

Souheil Hallit, Email: souheilhallit@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Gall TL, Malette J, Guirguis-Younger M. Spirituality and religiousness: a diversity of definitions. J Spirituality Mental Health. 2011;13(3):158–181. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abuhammad S, Alnatour A, Howard K. Intimidation and bullying: a school survey examining the effect of demographic data. Heliyon. 2020;6(7):e04418. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metz HC: Saudi Arabia: A country study, vol. 550: Division; 1993.

- 4.Aljneibi NM: Well-being in the United Arab Emirates: how findings from positive psychology can inform government programs and research. 2018.

- 5.Miller T. Mapping the global Muslim population: a report on the size and distribution of the world’s Muslim population. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ketola J, Stein JV. Psychiatric clinical course strengthens the student-patient relationships of baccalaureate nursing students. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2013;20(1):23–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2012.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daher-Nashif S, Hammad SH, Kane T, Al-Wattary N. Islam and mental disorders of the older adults: religious text, belief system and caregiving practices. J Relig Health. 2021;60:2051–2065. doi: 10.1007/s10943-020-01094-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fekih-Romdhane F, Tounsi A, Ben Rejeb R, Cheour M. Is religiosity related to suicidal ideation among Tunisian Muslim youth after the January 14th revolution? Community Ment Health J. 2020;56:165–173. doi: 10.1007/s10597-019-00447-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(2):175–183. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamdan A. Mental health needs of Arab women. Health Care Women Int. 2009;30(7):593–611. doi: 10.1080/07399330902928808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng TP, Nyunt MSZ, Chiam PC, Kua EH. Religion, health beliefs and the use of mental health services by the elderly. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(2):143–149. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.508771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amawi N, Mollica RF, Lavelle J, Osman O, Nasir L. Overview of research on the mental health impact of violence in the Middle East in light of the Arab Spring. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(9):625–629. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gearing RE, MacKenzie MJ, Ibrahim RW, Brewer KB, Batayneh JS, Schwalbe CS. Stigma and mental health treatment of adolescents with depression in Jordan. Community Ment Health J. 2015;51:111–117. doi: 10.1007/s10597-014-9756-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Organization WH: The World Health Report 2001: Mental health: new understanding, new hope. 2001.

- 15.Rössler W. The stigma of mental disorders: a millennia-long history of social exclusion and prejudices. EMBO Rep. 2016;17(9):1250–1253. doi: 10.15252/embr.201643041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bushong EC: The relationship between religiosity and mental illness stigma in the Abrahamic religions. 2018.

- 17.Fanegan B, Berry A-M, Combs J, Osborn A, Decker R, Hemphill R, Barzman D. Systematic review of religiosity's relationship with suicidality, suicide related stigma, and formal mental health service utilization among black Americans. Psychiatr Q. 2022;93(3):775–782. doi: 10.1007/s11126-022-09985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crowe A, Averett P, Glass JS, Dotson-Blake KP, Grissom SE, Ficken DK, Holmes J. Mental health stigma: Personal and cultural impacts on attitudes. J Counselor Pract. 2016;7(2):97–119. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson-Kwochka AV, Stull LG, Salyers MP. The impact of diagnosis and religious orientation on mental illness stigma. Psychol Relig Spiritual. 2022;14:462–472. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi N-Y, Kim HY, Gruber E. Mexican American women college students’ willingness to seek counseling: the role of religious cultural values, etiology beliefs, and stigma. J Couns Psychol. 2019;66(5):577. doi: 10.1037/cou0000366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wesselmann ED, Graziano WG. Sinful and/or possessed? Religious beliefs and mental illness stigma. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2010;29(4):402–437. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peteet JR. Approaching religiously reinforced mental health stigma: a conceptual framework. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(9):846–848. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abuhammad S, Al-Natour A. Mental health stigma: the effect of religiosity on the stigma perceptions of students in secondary school in Jordan toward people with mental illnesses. Heliyon. 2021;7(5):e06957. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Natour A, Abuhammad S, Al-Modallal H. Religiosity and stigma toward patients with mental illness among undergraduate university students. Heliyon. 2021;7(3):e06565. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Krenawi A, Graham JR. Culturally sensitive social work practice with Arab clients in mental health settings. Health Soc Work. 2000;25(1):9–22. doi: 10.1093/hsw/25.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zolezzi M, Bensmail N, Zahrah F, Khaled SM, El-Gaili T. Stigma associated with mental illness: perspectives of university students in Qatar. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:1221–1233. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S132075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.AH AL, Alshammari SN, Alshammari KA, Althagafi AA, AlHarbi MM. Public awareness, beliefs and attitude towards depressive disorders in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2021;42(10):1117–1124. doi: 10.15537/smj.2021.42.10.20210425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Adawi S, Dorvlo AS, Al-Ismaily SS, Al-Ghafry DA, Al-Noobi BZ, Al-Salmi A, Burke DT, Shah MK, Ghassany H, Chand SP. Perception of and attitude towards mental illness in Oman. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2002;48(4):305–317. doi: 10.1177/002076402128783334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jelaidan M, AbuAlkhair L, Thani T, Susi A, Shuqdar R. General background and attitude of the Saudi population owards mental illness. Egypt J Hospital Med. 2018;71(1):2422–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heath PJ, Vogel DL, Al-Darmaki FR. Help-seeking attitudes of United Arab Emirates students: examining loss of face, stigma, and self-disclosure. Couns Psychol. 2016;44(3):331–352. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fekih-Romdhane F, Chebbi O, Sassi H, Cheour M. Knowledge, attitude and behaviours toward mental illness and help-seeking in a large nonclinical Tunisian student sample. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2021;15(5):1292–1305. doi: 10.1111/eip.13080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aldalaykeh M, Al-Hammouri MM, Rababah J. Predictors of mental health services help-seeking behavior among university students. Cogent Psychology. 2019;6(1):1660520. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al Omari O, Khalaf A, Al Sabei S, Al Hashmi I, Al Qadire M, Joseph M, Damra J. Facilitators and barriers of mental health help-seeking behaviours among adolescents in Oman: a cross-sectional study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2022;76(8):591–601. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2022.2038666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dardas LA, Silva SG, van de Water B, Vance A, Smoski MJ, Noonan D, Simmons LA. Psychosocial correlates of Jordanian adolescents’ help-seeking intentions for depression: findings from a nationally representative school survey. J School Nurs. 2019;35(2):117–127. doi: 10.1177/1059840517731493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al-Shannaq Y, Aldalaykeh M. Suicide literacy, suicide stigma, and psychological help seeking attitudes among Arab youth. Curr Psychol. 2021;42:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02007-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.AlHorany AK. Attitudes toward help-seeking counseling, stigma in Arab context: a systematic literature review. Malaysian J Med Health Sci. 2019;15:160–167. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fekih-Romdhane F, Amri A, Cheour M. Suicidal ideation, suicide literacy and stigma, disclosure expectations and attitudes toward help-seeking among university students: the impact of schizotypal personality traits. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2022;16(6):659–669. doi: 10.1111/eip.13211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merhej R. Stigma on mental illness in the Arab world: beyond the socio-cultural barriers. Int J Human Rights Healthcare. 2019;12(4):285–98. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aloud N, Rathur A. Factors affecting attitudes toward seeking and using formal mental health and psychological services among Arab Muslim populations. J Muslim Mental Health. 2009;4(2):79–103. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rudwan SJ, Al Owidha SM. Perceptions of mental health disorders: an exploratory study in some arab societies. Int J Dev Res. 2019;9(01):25369–25383. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dardas L, Simmons LA. The stigma of mental illness in Arab families: a concept analysis. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2015;22(9):668–679. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sewilam AM, Watson AM, Kassem AM, Clifton S, McDonald MC, Lipski R, Deshpande S, Mansour H, Nimgaonkar VL. Suggested avenues to reduce the stigma of mental illness in the Middle East. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2015;61(2):111–120. doi: 10.1177/0020764014537234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ciftci A, Jones N, Corrigan PW: Mental health stigma in the Muslim community. Journal of Muslim Mental Health 2013, 7(1).

- 44.Fekih-Romdhane F, Jahrami H, Stambouli M, Alhuwailah A, Helmy M, Shuwiekh HAM. Lemine CMfM, Radwan E, Saquib J, Saquib N: Cross-cultural comparison of mental illness stigma and help-seeking attitudes: a multinational population-based study from 16 Arab countries and 10,036 individuals. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol. 2022;58:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s00127-022-02403-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henning-Smith C, Shippee TP, McAlpine D, Hardeman R, Farah F. Stigma, discrimination, or symptomatology differences in self-reported mental health between US-born and Somalia-born Black Americans. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):861–867. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.May S, Rapee RM, Coello M, Momartin S, Aroche J. Mental health literacy among refugee communities: differences between the Australian lay public and the Iraqi and Sudanese refugee communities. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(5):757–769. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0793-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slewa-Younan S, Mond J, Bussion E, Mohammad Y, Uribe Guajardo MG, Smith M, Milosevic D, Lujic S, Jorm AF. Mental health literacy of resettled Iraqi refugees in Australia: knowledge about posttraumatic stress disorder and beliefs about helpfulness of interventions. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0320-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bener A, Ghuloum S. Ethnic differences in the knowledge, attitude and beliefs towards mental illness in a traditional fast developing country. Psychiatria Danubina. 2011;23(2):157–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Younis MS, Anwer AH, Hussain HY. Stigmatising attitude and reflections towards mental illness at community setting, population-based approach, Baghdad City 2020. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;67(5):461–466. doi: 10.1177/0020764020961797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malygin YV, Tsygankov D, Malygin V, Shamov S. A multifactorial model of the medical help-seeking behavior of patients with depressive and neurotic disorders. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2020;50:30–34. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fekih-Romdhane F, Hamdi F, Jahrami H, Cheour M. Attitudes toward schizophrenia among Tunisian family medicine residents and non-medical students. Psychosis. 2022;15(2):168–180. doi: 10.1080/17522439.2022.2032291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alenezi AF, Aljowder A, Almarzooqi MJ, Alsayed M, Aldoseri R, Alhaj O, Souraya S, Thornicroft G, Jahrami H. Translation and validation of the Arabic version of the barrier to access to care evaluation (BACE) scale. Mental Health Soc Inclusion. 2021;25(4):352–65. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, Bezborodovs N, Morgan C, Rüsch N, Brown JS, Thornicroft G. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med. 2015;45(1):11–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schnyder N, Panczak R, Groth N, Schultze-Lutter F. Association between mental health-related stigma and active help-seeking: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210(4):261–268. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.189464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu Z, Huang F, Kösters M, Staiger T, Becker T, Thornicroft G, Rüsch N. Effectiveness of interventions to promote help-seeking for mental health problems: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2018;48(16):2658–2667. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718001265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burns JK, Tomita A. Traditional and religious healers in the pathway to care for people with mental disorders in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(6):867–877. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0989-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Okasha A, Karam E, Okasha T. Mental health services in the Arab world. World Psychiatry. 2012;11(1):52–54. doi: 10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fekih-Romdhane F, Daher-Nashif S, Stambouli M, Alhuwailah A, Helmy M, Shuwiekh HAM, et al. Suicide literacy mediates the path from religiosity to suicide stigma among Muslim community adults: cross-sectional data from four Arab countries. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2023:207640231174359. 10.1177/00207640231174359. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Taylor SM, Dear MJ. Scaling community attitudes toward the mentally ill. Schizophr Bull. 1981;7(2):225–240. doi: 10.1093/schbul/7.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abi Doumit C, Haddad C, Sacre H, Salameh P, Akel M, Obeid S, Akiki M, Mattar E, Hilal N, Hallit S, et al. Knowledge, attitude and behaviors towards patients with mental illness: results from a national Lebanese study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(9):e0222172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fischer EH, Farina A: Attitudes toward seeking professional psychologial help: A shortened form and considerations for research. Journal of college student development 1995.

- 62.Khalaf DR, Hlais SA, Haddad RS, Mansour CM, Pelissolo AJ, Naja WJ. Developing and testing an original Arabic religiosity scale. Middle East Current Psychiatry. 2014;21(2):127–138. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alahmed S, Anjum I, Masuadi E. Perceptions of mental illness etiology and treatment in Saudi Arabian healthcare students: a cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Med. 2018;6:2050312118788095. doi: 10.1177/2050312118788095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alhomaizi D, Alsaidi S, Moalie A, Muradwij N, Borba CP, Lincoln AK. An exploration of the help-seeking behaviors of Arab-Muslims in the US: a socio-ecological approach. J Muslim Ment Health. 2018;12(1):19–48. doi: 10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0012.102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gunson D, Nuttall L, Akhtar S, Khan A, Avian G, Thomas L: Spiritual beliefs and mental health: a study of Muslim women in Glasgow. 2019.

- 66.Hamid A, Furnham A. Factors affecting attitude towards seeking professional help for mental illness: a UK Arab perspective. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2013;16(7):741–758. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Al-Darmaki F, Thomas J, Yaaqeib S. Mental health beliefs amongst emirati female college students. Community Ment Health J. 2016;52(2):233–238. doi: 10.1007/s10597-015-9918-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Al-Darmaki F, Sayed M. Counseling challenges within the cultural context of the United Arab Emirates. International handbook of cross-cultural counseling: Cultural assumptions and practices worldwide; 2009. p. 465–74.

- 69.AbdAleati NS, Mohd Zaharim N, Mydin YO. Religiousness and mental health: systematic review study. J Relig Health. 2016;55(6):1929–1937. doi: 10.1007/s10943-014-9896-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lukachko A, Myer I, Hankerson S. Religiosity and mental health service utilization among African Americans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(8):578. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pickard JG. The relationship of religiosity to older adults’ mental health service use. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10(3):290–297. doi: 10.1080/13607860500409641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harris KM, Edlund MJ, Larson SL. Religious involvement and the use of mental health care. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(2):395–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00500.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mahfoud D, Fawaz M, Obeid S, Hallit S. The co-moderating effect of social support and religiosity in the association between psychological distress and coping strategies in a sample of lebanese adults. BMC Psychol. 2023;11(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s40359-023-01102-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Newton AT, McIntosh DN. Specific religious beliefs in a cognitive appraisal model of stress and coping. Intern J Psychol Religion. 2010;20(1):39–58. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lechner CM, Silbereisen RK, Tomasik MJ, Wasilewski J. Getting going and letting go: religiosity fosters opportunity-congruent coping with work-related uncertainties. Int J Psychol. 2015;50(3):205–214. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lukachko A, Myer I, Hankerson S. Religiosity and mental health service utilization among African-Americans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(8):578–582. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rassool GH: Evil eye, jinn possession, and mental health issues: An Islamic perspective: Routledge; 2018.

- 78.Hair Jr JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Danks NP, Ray S, et al. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: a workbook. Springer Nature; 2021. p. 197.

- 79.Obermeyer CM. Adolescents in Arab countries: health statistics and social context. DIFI Family Res Proceed. 2015;2015(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Al-Krenawi A, Graham JR, Al-Bedah EA, Kadri HM, Sehwail MA. Cross-national comparison of Middle Eastern university students: help-seeking behaviors, attitudes toward helping professionals, and cultural beliefs about mental health problems. Community Ment Health J. 2009;45(1):26–36. doi: 10.1007/s10597-008-9175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Koschorke M, Evans-Lacko S, Sartorius N, Thornicroft G. Stigma in different cultures. In: Gaebel W, Rössler W, Sartorius N, editors. The Stigma of Mental Illness - End of the Story? Cham: Springer; 2017. 10.1007/978-3-319-27839-1_4.

- 82.Gearing RE, Schwalbe CS, MacKenzie MJ, Brewer KB, Ibrahim RW, Olimat HS, Al-Makhamreh SS, Mian I, Al-Krenawi A. Adaptation and translation of mental health interventions in Middle Eastern Arab countries: a systematic review of barriers to and strategies for effective treatment implementation. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2013;59(7):671–681. doi: 10.1177/0020764012452349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pawluk SA, Zolezzi M. Healthcare professionals’ perspectives on a mental health educational campaign for the public. Health Educ J. 2017;76(4):479–491. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Semrau M, Evans-Lacko S, Koschorke M, Ashenafi L, Thornicroft G. Stigma and discrimination related to mental illness in low-and middle-income countries. Epidemiol Psychiatric Sci. 2015;24(5):382–394. doi: 10.1017/S2045796015000359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sartorius N, Schulze H: Reducing the stigma of mental illness: a report from a global association: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are not publicly available due the restrictions from the ethics committee. Reasonable requests can be addressed to the corresponding author.