Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors have been shown to be well tolerated among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and psoriasis. Meanwhile, more recently, clinical practice and research efforts have uncovered increasing cases of psoriatic lesion development tied to initiating treatment with a TNF-α inhibitor. The underlying mechanisms associated with this occurrence have yet to be fully elucidated. A review and analysis of cases of paradoxical psoriasis currently published in the literature is warranted. In addition, exploring possible mechanisms of action and potential treatment options associated with favorable outcomes is much needed.

A systematic literature review was performed utilizing PubMed and Google Scholar databases (1992-present), in which 106 cases of paradoxical psoriasis were reviewed. The most common morphology developed was plaque psoriasis vulgaris. There was a female predominance (61.3%), and the most common underlying autoimmune disease was rheumatoid arthritis (45.3%). In addition, the most commonly associated drug with the onset of psoriatic lesions was infliximab (62.3%). Furthermore, the findings suggest that the most well-supported mechanism of action involves the uncontrolled release of interferon-alpha (IFN-α) from plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) after TNF-α inhibition. While TNF-α inhibitors have been shown to have great benefits to patients with rheumatologic diseases, cases of paradoxical psoriasis demonstrate the importance of close monitoring of patients on TNF-α inhibitors to allow for early recognition, treatment, and potentially change to a different mechanism of action of the medication used to prevent further progression of the inflammatory lesions.

Keywords: pathogenesis, treatment, paradoxical, tnf-a inhibitor, psoriasis

Introduction and background

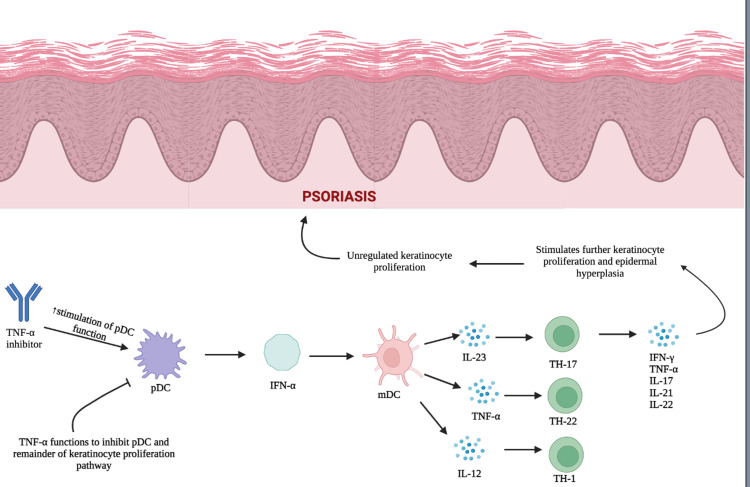

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) is a cytokine generated by activated macrophages, T-lymphocytes, neutrophils, and natural killer (NK) cells to regulate inflammatory responses. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha activates intracellular signaling pathways by binding to either TNF-receptor 1 (TNFR1) or TNF-receptor 2 (TNFR2) [1]. The binding of TNFR1 induces a pro-inflammatory response and apoptosis, while TNFR2 binding triggers anti-inflammatory and cell survival pathways. The balance of TNFR1/TNFR2 signaling helps regulate cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, and death [2,3]. Excess production of TNF-α has been identified as a key factor in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and psoriasis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The pathogenesis of psoriasis: This figure illustrates the role of keratinocytes and interferon-alpha (IFN-α) in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) functions to inhibit plasmacytoid dendritic cell (pDC) maturation and the subsequent production of IFN-α. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibition results in unregulated IFN-α production by pDCs and further downstream activation of myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs). This represents the initiation phase of psoriasis, which stimulates the release of inflammatory cytokines and the activation of T-helper cells. Continued inflammatory cytokine production stimulates further keratinocyte proliferation and epidermal hyperplasia and results in the development of psoriatic lesions.

[4]

Image created with Biorender.com.

Due to the crucial role of TNF-α in the pathogenesis of these diseases, TNF-α inhibitors have revolutionized the treatment of autoimmune diseases, demonstrating increased efficacy compared to alternative treatments. Currently, five TNF-α inhibitors are being used. These drugs include infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, pegol, golimumab, and etanercept [1,5]. Although all the TNF-α inhibitors ultimately inhibit the TNF intracellular signaling pathway, they differ in their specific mechanisms of action. Infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab are bivalent immunoglobulin G (IgG) monoclonal antibodies that competitively inhibit TNF by blocking the interaction of TNFR1 and TNFR2 receptors with TNF. Etanercept is unique as it is a human dimeric fusion protein that binds to TNF with a significantly higher affinity and forms complexes that inhibit TNF from binding to its receptors, further allowing the signaling pathway to continue [6].

Psoriasis is an autoimmune T-cell-mediated disease of the skin characterized by sustained inflammation in the stratum corneum, which stimulates abnormal keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation [7]. A mouse model study demonstrated that the development of psoriatic lesions is dependent on the activation and replication of resident T cells that stimulate epidermal hyperplasia and an angiogenic reaction [8]. It is thought that the proliferation of resident T cells is driven by interferon-alpha/beta (IFN-α/B) production. After skin trauma, infection, or reaction to certain medications, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) can infiltrate the skin and secrete IFN-α, which is hypothesized to be the initial step in the development of psoriasis [9,10]. This idea is supported by a 2004 study that found IFN-α production was increased only in the early stages of psoriasis development, yet psoriatic plaques did not show elevated levels of IFN-α [8]. The initial production of Type 1 IFN (IFN-α and IFN-B) then initiates a cascade of cytokine secretion via effector T cells, mainly TH1 and TH17, which results in the production of IFN-γ and interleukin-17 (IL-17), IL-21, and IL-22. Simultaneously, activated myeloid dendritic cells (mDCs) begin to secrete TNF-α, IL-23, and IL-12. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-17, and IL-23 then function to sustain the maintenance phase of psoriatic inflammation by activating keratinocyte proliferation in the epidermis and the development of plaque-type psoriatic lesions [7].

As the inflammatory response cascades, increased circulating TNF-α results in the infiltration of inflammatory cells from the blood into the skin and dendritic cell activation. TNF-α also increases the activation of keratinocytes, promotes epidermal hyperplasia, and stimulates the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) inflammatory pathway to further increase the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [11]. A 2004 study using mouse models highlighted the role of TNF-α in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Pre-psoriatic human skin was engrafted onto 12 mice deficient in Type 1 and 2 interferon receptors (AGR129 mice), which resulted in the development of psoriatic lesions in 90% of the mice. Treatment of mice with TNF-α inhibitors resulted in a significant reduction of T cells in psoriatic lesions. This study strongly supports the role TNF-α plays in the development of psoriatic lesions and that the proliferation of T cells in lesions is dependent on TNF-α production [8]. Due to the central role TNF-α plays in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, TNF-α inhibitors were the first biologic drug approved for the treatment of psoriasis.

However, increasing numbers of cases of paradoxical development of psoriasis in patients with autoimmune diseases treated with TNF-α inhibitors have been reported in the literature. The first case of paradoxical psoriasis induced by TNF-α inhibitors was reported in 2004, but with increasing usage of TNF-α inhibitors, more cases are being reported. The current incidence of paradoxical psoriasis lesions is 2%-5% [12]. Currently, there are more than 100 reports of patients who developed psoriasis after beginning treatment with a TNF-α inhibitor for the management of an alternative autoimmune disease.

Although the number of cases of paradoxical psoriasis continues to increase, there is still no clear mechanism of action established and little research evaluating the treatments that result in the best outcomes for patients who develop these lesions. In this review, we aim to review the current literature regarding proposed mechanisms of action and published cases of TNF-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis. Based on our analysis, we aim to propose treatment options that will help guide clinicians in managing patients to allow for better patient outcomes with complete remission of psoriatic lesions.

Proposed mechanisms of action

Although the mechanism of action tied to the development of psoriatic lesions has yet to be fully elucidated, there are several well-supported theories on the mechanism by which TNF-α inhibitors result in psoriatic lesion development. The most accepted theory is that the TNF-α inhibitor leads to uncontrolled production of IFN-α by pDCs. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells have been found to be increased in the pre-psoriatic skin of psoriasis patients and appear to initiate autoimmune inflammation leading to psoriatic lesion formation. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells infiltrate the skin and produce a surge of IFN-α. As a result, excess levels of IFN-α activate myeloid dendritic cells, which then stimulate pathogenic T cells. This results in the release of the inflammatory cytokines IL-23, TNF-α, and IL-12, which activate T helper cells, stimulate further inflammatory cytokine release and result in unregulated keratinocytes [9]. A study using a human xenograft model of psoriasis demonstrated that blocking IFN-α signaling via treatment with neutralizing antibodies to the IFN-α receptor resulted in the inhibition of both activation and expansion of pathogenic T cells and abrogated the development of psoriatic lesions in mice [9]. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibits both pDC maturation and IFN-α production. Consequently, inhibition of TNF-α can result in unregulated IFN-α production by pDCs and, in turn, the development of psoriatic lesions. When the psoriatic lesion was examined histologically, IFN-α was found to have increased expression in dermal vascular and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates [13].

In addition to the effect of TNF-α inhibitors on IFN-α and pDCs, it appears that TNF-α inhibitors may also upregulate the production of TH1 and TH17 cells. A 2014 study was the first to show that an increased number of IFN-γ-secreting TH1 and IL-17/IL-22-secreting TH17 cells were found in patients who developed TNF-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis, suggesting a potential link between TNF-α inhibitor treatment and increases in cytokines strongly associated with psoriasis, such as IL-17 and IL-22 [14].

Furthermore, TNF-α inhibitors may also lead to abnormal lymphocyte migration and upregulated expression of CXCR3 ligands, which have been shown to be involved in the development of psoriatic lesions [14]. Meanwhile, few studies have evaluated the correlation between CXCR3 ligands and cases of paradoxical psoriasis.

As opposed to classical psoriasis, it does not appear that auto-reactive T cells are involved in paradoxical psoriasis. In a T-cell-depleted mouse model, treatment with TNF-α inhibitors resulted in paradoxical psoriatic lesion development as a result of an overactive Type 1 IFN-driven inflammatory response. The paradoxical psoriatic lesions had increased dermal accumulation of pDCs, reduced T cell numbers, and higher levels of Type-1 interferon expression when compared with classical psoriatic lesions. [15] This data strongly suggests that paradoxical psoriasis onset is a drug-related side effect, wherein inflammation sustains a positive feedback loop in the innate immune response. Meanwhile, future studies are needed to evaluate new treatment modalities that target pDCs and Type 1 IFN to prevent the development of paradoxical psoriasis [15]. It is also still unclear what triggers the activation of pDCs that leads to the development of paradoxical psoriasis. There has been some suggestion that the presence of IL23R, FBXL19, CTLA4, SLC12A8, and TAP1 polymorphisms may be involved; however, the exact mechanism of action resulting in the development of lesions is still unclear [16].

Review

Methods

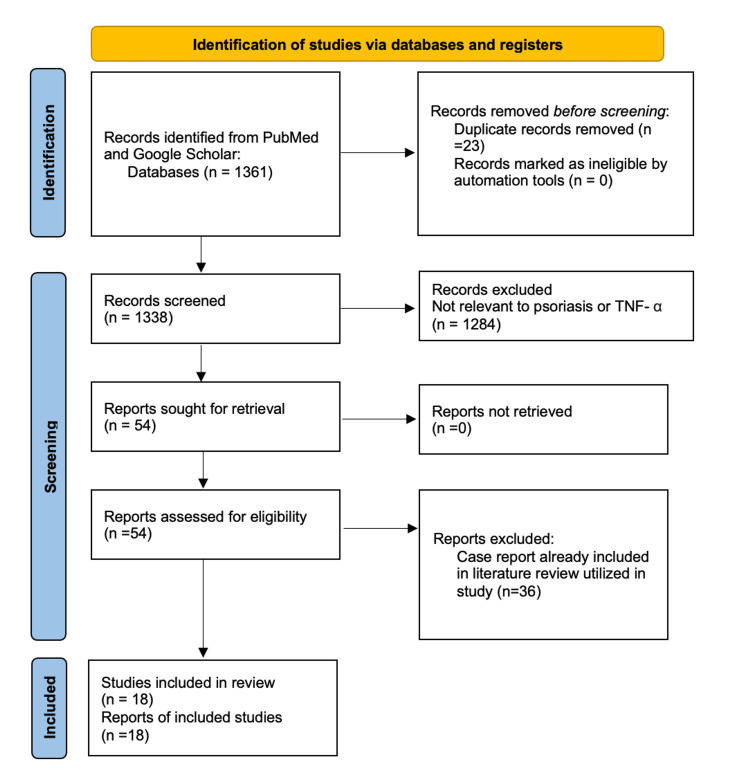

A systematic literature review was performed utilizing the PubMed and Google Scholar databases (1992-present). Search terms included "tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor," "TNF-α," and "paradoxical psoriasis" combined with the terms "psoriasis," "pathogenesis," and "treatment." After considering inclusion and exclusion criteria, 18 peer-reviewed publications were identified and utilized (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) chart of the 18 articles included in this review.

In addition, we performed an electronic literature search to identify case reports that documented the development of psoriatic lesions after beginning treatment with a TNF-α inhibitor. One hundred and six case reports were included in the final analysis. In each case, the patient's age, the disease being treated, the morphology of psoriasis lesions, and the treatment of lesions combined with the outcome were evaluated and summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Collective data of 106 patients who developed paradoxical psoriasis after TNF-α inhibitor treatment.

RA: rheumatoid arthritis; UC: ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s disease; AS: ankylosing spondylitis; SPA: spondyloarthritis; SAPHO: synovitis acne hyperostosis osteitis; PsA: psoriatic arthritis; HS: hidradenitis suppurativa; UVB: ultraviolet B

| Reference (year) | Primary Disease | Patients Age/Sex | TNF-a Inhibitor | Duration of Treatment | Family/Personal Hx of Psoriasis | Morphology of Lesion | Treatment | Outcome |

| Jarrett et al., 2003 [17] | RA | 60/F | Infliximab | 6 weeks | Not Specified | Palmoplantar Pustular Psoriasis | Discontinuation + Oral Prednisolone | Resolution |

| Thurber et al., 2004 [18] | UC | 36/M | Infliximab | 24 weeks | No | PS and Palmoplantar PS | Topical Corticosteroids, UV-B | Resolution |

| Verea et al., 2004 [19] | CD | 46/F | Infliximab | 6-8 weeks | No | Psoriatic Dermatitis | Discontinuation + Topical Steroids | Resolution |

| Beuthein et al., 2004 [20] | RA | 63/F | Adalimumab | 6 weeks | No | Papulopustular Exanthema | Discontinuation | Resolution |

| Dereure et al., 2004 [21] | RA | 47/F | Infliximab | 2 months | No | Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids + Salicylic Acid | Partial Resolution |

| RA | 55/F | Infliximab | 3 months | No | Psoriasis | Topical corticosteroids + Vitamin D + UV-B | Partial Resolution | |

| Habel et al., 2004 [22] | AS | 32/M | Infliximab | 8 weeks | No | Psoriasis | Discontinuation + Topical Corticosteroid | Partial Resolution |

| AS | 27/F | Infliximab | 10 months | No | Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Discontinuation + Systemic Corticosteroid | Partial Resolution | |

| AS | 25/M | Etanercept | 7 months | Family History | Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Discontinuation + Topicals | Partial Resolution | |

| Sfikakis et al., 2005 [23] | AS | 33/F | Infliximab | 9 months | No | Psoriasis and Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Switched to Etanercept | Partial Resolution |

| RA | 65/F | Adalimumab | 8 months | No | Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids | Resolution | |

| Behçet's Disease | 49/M | Infliximab | 6 months | No | Psoriasis and Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids | Slight Improvement | |

| Behçet's Disease | 43/M | Infliximab | 6 months | No | Psoriasis and Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids | Resolution | |

| RA | 48/F | Etanercept | 6 months | No | Psoriasis and Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Discontinuation + Topical Corticosteroids | Partial Resolution | |

| Grinblat and Scheinberg [24] | RA | 37/F | Infliximab | 7-9 infusions | No | Psoriasis | Acitretin | Not Tolerated |

| Michaelson et al., 2005 [25] | RA | 62/F | Infliximab | 8 weeks | Personal History | Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroid | Resolution |

| RA | 50/F | Infliximab | 8 weeks | No | Psoriasis | Discontinuation | Resolution | |

| Starmans-Kool et al., 2005 [26] | AS/CD | 41/M | Infliximab | 4 infusions | Not Specified | Pustular Psoriasis | Topical Clobetasol + Restarted Infliximab Months Later | Resolution |

| RA | 62/F | Infliximab | 5 infusions | Not Specified | Pustular Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Topical Clobetasol + Sulfasalazine + Restart Infliximab 1 Month Later | Resolution | |

| Peramiquel et al., 2005 [27] | CD | 29/F | Infliximab | 9 infusions | No | Intertriginous PS | Topical Corticosteroid PUVa | Partial Resolution |

| Zamitski et al., 2005 [28] | RA | 50/F | Adalimumab | 3 months | Not Specified | Palmoplantar Pustulosis | Topical Corticosteroids | Improvement |

| Kary et al., 2005 [29] | RA | 69/F | Etanercept | 1 month | Personal History | Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Discontinuation | Resolution |

| RA | 65/F | Adalimumab | 4 days | No | Pulstulosis Psoriasis Vulgaris | Discontinuation | Resolution | |

| RA | 38/M | Infliximab | 3 months | Family History | Psoriasis Vulgaris | Changed to Etanercept | Improvement + Reappearance of Lesions After 6 Weeks | |

| RA | 67/F | Adalimumab | 5 months | Family History | Psoriasis Pustulosa | Discontinuation | No Improvement | |

| RA | 49/F | Infliximab | 8 months | Personal History | Psoriasis Pustulosa | Topical Corticosteroid | Improvement | |

| RA | 49/F | Etanercept | 1 month | Personal History | Psoriasis Vulgaris | Methotrexate Added + Topical Corticosteroid | Not Specified | |

| RA | 63/F | Etanercept | 2 months | No | Psoriasis Vulgaris | No Treatment | Stable | |

| RA | 40/F | Adalimumab | 11 months | No | Psoriasis Vulgaris | Discontinuation + Cyclosporin Started, Then Switched to Infliximab | No Improvement | |

| Adams et al., 2006 [30] | UC | 32/F | Infliximab | 2 months | No | Palmoplantar Pustulosis | Topical Corticosteroid | Partial Resolution |

| CD | 19/M | Infliximab | 17 months | No | Palmoplantar Pustulosis | Topical Corticosteroid | Partial Resolution | |

| Matthews et al., 2006 [31] | AS | 49/F | Infliximab | 8 months | No | Pustular Psoriasis | Increasing Methotrexate Dose | Resolution |

| PsA | 68/F | Infliximab | Not Specified | Personal History | Intertriginous Psoriasis | Topical Treatment | Resolution | |

| RA | 54/F | Adalimumab | 10 months | No | Psoriasis | No Treatment | Resolution | |

| Goiriz et al., 2007 [32] | RA | 55/M | Adalimumab | 20 months | No | Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Discontinuation + Adalimumab | Significant improvement |

| AS | 32/M | Infliximab | 5 months | No | Plantar Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids | Partial Resolution | |

| PS | 52/M | Etanercept | 2 months | Personal History | Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids | Improvement | |

| PS | 42/F | Etanercept | 15 days | Personal History | Psoriasis | Cyclosporine | Remission | |

| PS | 54/F | Etanercept | 1 month | Personal History | Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids | Improvement | |

| PS | 40/M | Etanercept | 14 months | Personal History | Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids | Improvement | |

| PS | 58/F | Etanercept | 3 months | Personal History | Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids | Improvement | |

| PS | 56/M | Etanercept | 18 months | Personal History | Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids | Improvement | |

| Sari et al., 2006 [33] | RA | 30/F | Etanercept | 2 months | No | Psoriasis | Discontinuation + Corticosteroid | Resolution |

| Pirard et al., 2006 [34] | CD | 19/F | Infliximab | 3 years | Family History | Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids | Improved |

| RA | 47/F | Infliximab | 5th infusion | No | Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids | Resolution | |

| AS | 29/F | Infliximab | 9th infusion | No | Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids | Improved | |

| Volpe et al., 2006 [35] | RA | 70/F | Infliximab | 9th infusion | No | Psoriasis | Discontinuation + Calcipotriene Ointment | Resolution |

| AS | 50/M | Infliximab | 4 months | No | Psoriasis | Calcipotriene Ointment | Improvement | |

| Gonzalez-Lopez et al., 2006 [36] | CD | 39/M | Infliximab | 1 month | No | Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Discontinuation + Corticosteroid | Resolution |

| Aslanidis et al., 2007 [37] | RA | 64/F | Adalimumab | 18 months | Not Specified | Plaque Psoriasis | Topical Agents | Resolution |

| RA | 62/F | Adalimumab | Not Specified | Plantar Pustulosis | Topical Agents | Resolution | ||

| AS | 24/F | Infliximab | 8 months | Not Specified | Palmar Pustulosis | Cyclosporine | Improvement | |

| RA | 29/F | Infliximab | 24 months | Not Specified | Plaque Psoriasis | - | Improvement | |

| SpA | 57/M | Infliximab | 3 months | Not Specified | Guttate Psoriasis | Topical Agents | Resolution | |

| RA | 76/F | Infliximab | 18 months | Not Specified | Plaque Psoriasis | Topical Agents | Resolution | |

| RA | 63/M | Infliximab | 14 months | Not Specified | Palmar Pustulosis/Guttate Psoriasis | Cyclosporine | Improvement | |

| Behcet's Disease | 60/M | Infliximab | 1.5 months | Not Specified | Palmoplantar Pustulosis | Discontinuation | Resolution | |

| AS | 57/M | Infliximab | 3 months | Not Specified | Palmoplantar Pustulosis | Topical Agents/Cyclosporine | Improvement | |

| RA | 47/M | Infliximab | 26 months | Not Specified | Plaque Psoriasis | Topical Agents | Improvement | |

| RA | 60/M | Infliximab | 4 months | Not Specified | Palmar Pustulosis | - | Stable | |

| AS | 37/M | Infliximab | 42 months | Not Specified | Guttate Psoriasis | - | Resolution | |

| Roux et al., 2007 [38] | RA | 42/F | Infliximab | 30 months | None | Palmoplantar Pustulosis | None | Resolution |

| RA | 32/F | Infliximab | 7 months | None | Palmoplantaris Pustulosis | Discontinuation, Etanercept | Resolution | |

| Severs et al., 2007 [39] | UC | 40/F | Infliximab | 10 months | Family History | Plaque Psoriasis | Discontinuation + UVB therapy | Improvement |

| CD | 38/M | Infliximab | 42 months | None | Plaque Psoriasis | UVB Therapy | Improvement | |

| CD | 21/M | Infliximab | 4 months | None | Pustular Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids | Improvement | |

| Ubriana and Van Voorhees e+B16t al., 2007 [40] | RA | 65/F | Infliximab | 8 weeks | No | Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Discontinuation + Corticosteroid | Resolution After 6 Months |

| De Gannes et al., 2007 [4] | RA | 41/F | Etanercept | 26 months | No | Palmoplantar Pustular Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids + Topical Calcipotriene | Resolution |

| Psoriatic Arthritis | 59/F | Infliximab | 12 months | Personal History | Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids + Topical Calcipotriene | Partial Resolution | |

| RA | 53/F | Etanercept | 17 months | Personal History | Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids + Topical Calcipotriene | Partial Resolution | |

| RA | 66/F | Etanercept | 4 months | No | Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids + Topical Calcipotriene | Resolution | |

| AS | 51/M | Etanercept | 12 months | No | Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids + Topical Calcipotriene | Partial Resolution | |

| RA | 48/F | Etanercept | 3 months | No | Pustular Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids + Topical Calcipotriene | Partial Resolution | |

| Juvenile RA | 19/F | Adalimumab | 3 months | Family History | Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids + Topical Calcipotriene | Partial Resolution | |

| RA | 41/F | Infliximab | 2 months | No | Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids + Topical Calcipotriene | Resolution | |

| RA | 52/F | Infliximab | 24 months | No | Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids + Topical Calcipotriene | Partial resolution | |

| RA | 78/F | Infliximab | 2 months | No | Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids + Topical Calcipotriene | Resolution | |

| RA | 57/M | Adalimumab | 62 months | No | Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids + Topical Calcipotriene | Partial resolution | |

| RA | 50/M | Infliximab | 12 months | No | Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids + Topical Calcipotriene | Resolution | |

| RA | 55/F | Adalimumab | 36 months | No | Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids + Topical Calcipotriene | Resolution | |

| RA | 49/M | Adalimumab | 5 months | No | Pustular Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids + Topical Calcipotriene | Resolution | |

| RA | 37/F | Etanercept | 24 months | No | Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids + Topical Calcipotriene | Partial Resolution | |

| Wollina et al., 2008 [41] | AS | 24/F | Infliximab | 8 weeks | Not specified | Pustular Psoriasis | Discontinuation + UVB Therapy and Etanercept | Resolution |

| CD | 22/M | Infliximab | 6 weeks | None | Pustular Exanthema | Discontinuation + Prednisolone | Resolution | |

| Pustular Psoriasis | 21/M | Adalimumab | 2 weeks | Not specified | Pustular Psoriasis | Discontinuation + Topical Steroids | Resolution | |

| SAPHO | 52/F | Adalimumab | 4 weeks | None | Pustular Palmoplantar Psoriasis | Discontinuation + Retinoid Acitretin and PUVA | Resolution | |

| RA | 59/F | Adalimumab | 7 months | None | Pustular Psoriasis | Discontinuation + Methotrexate, etanercept, and UVB | Resolution | |

| AS | 52/M | Infliximab | 2 years | Family History | Psoriatic Arthritis | Discontinuation + Topical Steroids | Resolution | |

| Manni & Barachini, 2009 [42] | CD | 30/F | Infliximab | 15 weeks | None | Palmoplantar Pustular Psoriasis | Discontinuation, Corticosteroids, Cyclosporine | Resolution |

| Nakagomi et al., 2009 [43] | RA | 69/F | Infliximab | 21 months | Not Specified | Palmoplantar Pustulosis | Discontinuation + Clobetasol and Ciclosporin | Resolution |

| Bruzzese & Pepe, 2019 [44] | CD | 29/M | Infliximab | 6 weeks | None | Palmoplantar Pustular Psoriasis | Discontinuation + Corticosteroid | Resolution |

| Andrew et al., 2010 [45] | Sarcoidosis | 58/M | Infliximab | 2 years | None | Spongiotic Psoriasiform Dermatitis | Topical Corticosteroids | Improvement |

| Oh et al., 2010 [46] | AS | 53/M | Etanercept | 3 years 7 months | Not Specified | Psoriasis | Discontinuation | Improvement |

| Pyrpasopoulou et al., 2010 [47] | AS | 53/M | Infliximab | 14 weeks | None | Palmoplantar pustulosis | Cyclosporine + Etanercept | Resolution |

| Rallis et al., 2010 [48] | PsA | - | Adalimumab | 6 months | Not Specified | Palmoplantar Pustular Psoriasis | - | - |

| Tresh et al., 2012 [49] | Behçet's Disease | 55/F | Infliximab | 6 weeks | None | Palmoplantar Pustular Psoriasis | Superficial Radiotherapy | Improvement |

| Kawashima et al., 2013 [50] | CD | 22/M | Infliximab | 8 weeks | Not Specified | Palmoplantar Pustulosis | Discontinuation + Topical Corticosteroids | Improvement |

| Broge et al., 2013 [51] | CD | 17/F | Infliximab | 24 weeks 8 weeks 6 weeks | None | Plaque Psoriasis, Psoriasis Vulgaris, Plaque Psoriasis | Discontinuation + Adalimumab | Resolution |

| CD | 14/M | Infliximab | 8 weeks | None | Psoriasis Vulgaris | Discontinuation + Prednisone and Adalimumab | Resolution | |

| CD | 13/M | Infliximab | 6 weeks | None | Plaque Psoriasis | Discontinuation + Topical Corticosteroids. UVB, and methotrexate | Resolution | |

| Peinado, 2015 [52] | CD | 32/F | Infliximab | 10 years | Not Specified | Scalp Psoriasis | Discontinuation, Corticosteroids, Methotrexate, Vitamin D | Resolution |

| Gulec et al., 2020 [53] | AS | 33/F | Adalimumab | 3 months | None | Pustular Psoriasis | Discontinuation, Etanercept, Methotrexate and Cyclosporine | Resolution |

| AS | 43/F | Infliximab | 3 years | None | Palmoplantar Pustular Psoriasis | Topical Corticosteroids | Improvement | |

| PsA | 56/F | Infliximab | 7 years | Personal History | PsA | Discontinuation + Secukinumab | Resolution | |

| Irkin et al., 2021 [54] | AS | 33/M | Adalimumab | 10 years | Not Specified | Palmoplantar, Onycholysis of the Nail, PS of Legs and Back | Discontinuation, Started IL-17 Inhibitor Secukinumab | Significant Regression of Rashes Persistence of Onycholysis |

| Kanelleas et al., 2022 [55] | HS | 4 pts (2M/2F) | Adalimumab | 5 months | 50% Had a Family History | Plaque Psoriasis | - | - |

Results

We identified 40 articles with 106 cases of new-onset TNF-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis (Table 1). Table 2 summarizes the patient demographics.

Table 2. A summary of patient demographics.

| Patients | Total Number (106) |

| Male | 41 (38.6%) |

| Female | 65 (61.3%) |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | 48 (45.3%) |

| Crohn's Disease (CD) | 16 (15%) |

| Ulcerative Colitis (UC) | 3 (2.8%) |

| Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS) | 19 (18%) |

| Hidradenitis Suppurativa | 1(0.9%) |

| Behçet's Disease | 4 (3.7%) |

| Infliximab | 66 (62.3%) |

| Adalimumab | 21 (19.8%) |

| Etanercept | 19 (17.9%) |

| Familial History of Psoriasis | 9 (8.4%) |

| Personal History of Psoriasis | 14 (13.2%) |

| History Not Specified | 13 (12.2%) |

| Resolution After Discontinuation | 18 (17%) |

| Resolution After Discontinuation + Switching TNF-α | 10 (9.4%) |

| Resolution With Continuing Anti-TNF + Corticosteroid | 13 (12.2%) |

| Partial Resolution After Discontinuation and No Steroid | 9 (8.5%) |

| Partial Resolution/Improvement With Continuing Anti-TNF + Corticosteroid | 26 (24.5%) |

As detailed in Table 2, 61.3% of patients were female and 38.6% were male, with the average age among patients being 45. The rate of developing paradoxical lesions ranged from four days to 10 years after the initiation of TNF-α inhibitors. The most common disease treated that led to the development of paradoxical psoriasis was rheumatoid arthritis (45.3% of patients). Fifteen percent were being treated for Crohn’s disease, 0.03% were being treated for ulcerative colitis, 18% were being treated for ankylosing spondylitis, 0.09% for Behçet's disease, and 0.09% were being treated for hidradenitis suppurativa. Infliximab was the most common TNF-α inhibitor used and resulted in cases of paradoxical psoriasis, totaling 62.3% of the cases reported. Adalimumab was the second most common with 19.8% of cases, followed by etanercept with 17.9% of cases. In addition, 13.2% of patients had a pre-existing personal history of psoriasis, and 0.8% of patients had a family history of psoriasis. The most common morphology developed was plaque psoriasis vulgaris (43%), with the second most common being palmoplantar pustular psoriasis (37.8%). A minority of patients developed two morphologies of psoriasis (6%), with the combination of palmoplantar psoriasis and psoriasis vulgaris being the most common. The most common outcome was partial resolution while continuing treatment with TNF-α inhibitors in conjunction with a topical corticosteroid (24.5%). Furthermore, 17% of patients saw full resolution of lesions after discontinuation of the TNF-α inhibitor or resolution after discontinuation and switching to a different TNF-α inhibitor (9.4%).

Discussion

This review focuses on cases of paradoxical psoriasis provoked by anti-TNF-α drug usage currently published in the literature. While TNF-α inhibitors have been proven to be effective in the majority of psoriasis patients, various cutaneous adverse reactions have been reported, such as erythema, vasculitis, edema, bullous lesions, and lichen planus-like dermatitis [56]. The development of various skin disorders such as psoriasis, lupus-like disorders, eczematiform lesions, and pustular folliculitis has also been reported [57,58]. The development of cutaneous side effects has been reported in several diseases, with autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (45.3%), Crohn’s disease (15%), and ankylosing spondylitis (18%) being the most common among the cases reviewed in this report. Diseases such as ulcerative colitis, Behçet's disease, and juvenile idiopathic arthritis have also been reported as less common causes of cutaneous side effects [41]. The literature suggests smoking, a family history of psoriasis, and the use of immunosuppressive therapies increase the risk of developing cutaneous side effects [59].

There is conflicting evidence regarding the histology of psoriatic lesions. A 2018 study suggested that histologic analysis of paradoxical psoriasis showed high variability among the lesions. Patients exhibited either an eczematiform spongiotic pattern, a psoriasis-like pattern with intraepidermal infiltrates, or a lichenoid pattern. This demonstrates that although some patients with paradoxical psoriasis developed the classic psoriasis histology, others had histopathologic evidence of differing diseases despite appearing to have psoriasis [15]. However, another study revealed that paradoxical psoriatic lesions demonstrate significantly increased levels of mast cells and eosinophils when compared to classical psoriasis lesions histologically. This further supports the theory that paradoxical psoriasis develops due to a different mechanism of action than classic psoriasis [60]. A recent study further supported these findings by showing that paradoxical psoriatic lesions have a marked increase in type-1 IFN expression coupled with a marked dermal accumulation of pDCs when compared with classic psoriasis. TNF-α inhibitors were found to prolong the ability of pDCs to produce type-1 IFN, which drives the differing phenotype of psoriatic lesions in paradoxical psoriasis [15].

In our analysis, the two most common morphologies of paradoxical psoriatic lesions were plaque psoriasis vulgaris and palmoplantar pustulosis (43% and 37.8%, respectively). However, the incidence of palmoplantar pustulosis in the general population with psoriasis is less than 20% [60]. This continues to support the hypothesis that paradoxical psoriasis develops via a different mechanism than classical psoriasis.

While the exact mechanism of action that induces the development of paradoxical psoriasis has yet to be fully elucidated, several well-supported theories continue to be evaluated. The most widely accepted theory implies a key role for pDCs and their production of IFN-α in the induction of psoriatic lesions. Since TNF-α functions to inhibit pDC maturation and IFN-α, TNF-α inhibition may allow for uncontrolled and unregulated production of IFN-α, consequently initiating inflammatory pathways involved in the onset of psoriatic lesions [9]. This idea has been further supported by the discovery of pDCs in early psoriatic lesions and in the skin of patients with autoimmune diseases that are absent in patients with healthy skin. Increased IFN-α expression has also been shown in the dermal vasculature of psoriatic lesions in patients on TNF-α inhibitor treatment [13]. However, further research is still needed to increase our knowledge of the pathogenesis and identify adverse effects.

In the cases reviewed, infliximab (62.3%) was the most reported TNF-α inhibitor to induce psoriatic lesions, with adalimumab (19.8%) being the second most common. This may be attributed to the more common usage of infliximab since it was the first TNF-α inhibitor to receive U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 1998 for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [61]. Whereas adalimumab was approved nine years later, in 2007, for Crohn’s disease [62]. In our analysis, the most common outcome was partial resolution while continuing treatment with TNF-α inhibitors in conjunction with a topical corticosteroid (24.5%). In addition, 17% of patients saw full resolution of lesions after discontinuation of the TNF-α inhibitor (17%) or resolution after discontinuation and switching to a different TNF-α inhibitor (9.4%). However, current literature demonstrates that in patients who chose to switch to a different TNF-α inhibitor, there was an eventual recurrence of lesions in the future [63]. A minority of patients also saw full resolution with the continuation of the TNF-α inhibitor and the addition of a corticosteroid (12.2%). Of those who discontinued treatment with TNF-α inhibitors, only 2% failed to see improvement in lesions. Current literature demonstrates a trend toward better outcomes in patients whose dermatologists initiated multi-modal treatment regimens such as combinations of topical corticosteroids, keratolytics, vitamin D analogs, and ultraviolet (UV)-light therapy [13]. Additionally, potential variables in our analysis of the results included insufficient data on how psoriasis was diagnosed among patients and if patients were on concurrent medications that could be related to the development of psoriatic lesions.

Based on our analysis, we suggest that patients discontinue treatment with their TNF-α inhibitor if another reasonable treatment option for their initial disease is available. Additionally, treatment with topical corticosteroids and phototherapy may be beneficial to those patients who develop mild psoriasis in order to aid in the quicker resolution of lesions. In patients who develop moderate-to-severe psoriasis with significant impacts on quality of life, treatment with methotrexate or systemic therapy allows for an increased probability of resolution. It is important for clinicians to implement close monitoring of patients upon starting treatment with TNF-α inhibitors to allow for early recognition and rapid initiation of treatment for complete resolution of lesions.

Conclusions

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors have proven to be effective drugs for various rheumatologic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel diseases. While TNF-α inhibitors are generally well tolerated among patients, increasing cases associated with psoriatic lesions after starting TNF-α inhibitor treatment have been reported. Based on our analysis, this sequela is most common in female patients and those using infliximab, which is most commonly associated with the onset of plaque psoriasis, as opposed to other psoriatic morphologies. Topical corticosteroids with discontinuation of TNF-α inhibitors may control or remit the psoriatic lesions. These cases demonstrate the importance of close monitoring of patients on TNF-α inhibitors for early recognition and treatment. Further research may provide a more detailed underlying immunological mechanism of paradoxical psoriasis and help target those individuals’ pre-initiation of TNF-inhibition who may have a predilection to develop paradoxical psoriasis.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.The role of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in autoimmune disease and current TNF-α inhibitors in therapeutics. Jang DI, Lee AH, Shin HY, et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22 doi: 10.3390/ijms22052719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.TNF in the inflammatory response. Männel DN, Echtenacher B. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10608086/ Chem Immunol. 2000;74:141–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Two TNF receptors. Tartaglia LA, Goeddel DV. Immunol Today. 1992;13:151–153. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90116-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Advances in the pathogenesis of psoriasis: from keratinocyte perspective. Zhou X, Chen Y, Cui L, Shi Y, Guo C. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41419-022-04523-3. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13:81. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-04523-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Psoriasis and pustular dermatitis triggered by TNF-{alpha} inhibitors in patients with rheumatologic conditions. de Gannes GC, Ghoreishi M, Pope J, et al. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:223–231. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors - state of knowledge. Lis K, Kuzawińska O, Bałkowiec-Iskra E. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10:1175–1185. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2014.47827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Psoriasis pathogenesis and treatment. Rendon A, Schäkel K. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:1475. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spontaneous development of psoriasis in a new animal model shows an essential role for resident T cells and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Boyman O, Hefti HP, Conrad C, Nickoloff BJ, Suter M, Nestle FO. J Exp Med. 2004;199:731–736. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plasmacytoid predendritic cells initiate psoriasis through interferon-alpha production. Nestle FO, Conrad C, Tun-Kyi A, et al. J Exp Med. 2005;202:135–143. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Defining upstream elements of psoriasis pathogenesis: an emerging role for interferon alpha. Nestle FO, Gilliet M. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:0. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pathogenesis of psoriasis and development of treatment. Ogawa E, Sato Y, Minagawa A, Okuyama R. J Dermatol. 2018;45:264–272. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paradoxical psoriasis induced by anti-TNFα treatment: evaluation of disease-specific clinical and genetic markers. Bucalo A, Rega F, Zangrilli A, et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:7873. doi: 10.3390/ijms21217873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Psoriatic skin lesions induced by tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy: a literature review and potential mechanisms of action. Collamer AN, Guerrero KT, Henning JS, Battafarano DF. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:996–1001. doi: 10.1002/art.23835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anti-TNF antibody-induced psoriasiform skin lesions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease are characterised by interferon-γ-expressing Th1 cells and IL-17A/IL-22-expressing Th17 cells and respond to anti-IL-12/IL-23 antibody treatment. Tillack C, Ehmann LM, Friedrich M, et al. Gut. 2014;63:567–577. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.TNF blockade induces a dysregulated type I interferon response without autoimmunity in paradoxical psoriasis. Conrad C, Di Domizio J, Mylonas A, et al. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-017-02466-4. Nat Commun. 2018;9:25. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02466-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Psoriasis: Classical vs. paradoxical. The yin-yang of TNF and type I interferon. Mylonas A, Conrad C. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02746/full. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2746. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy-induced vasculitis: case series. Jarrett SJ, Cunnane G, Conaghan PG, Bingham SJ, Buch MH, Quinn MA, Emery P. https://www.jrheum.org/content/30/10/2287.short. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2287–2291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pustular psoriasis induced by infliximab. Thurber M, Feasel A, Stroehlein J, Hymes SR. https://europepmc.org/article/med/15303790. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:439–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Psoriasiform eruption induced by infliximab. Verea MM, Del Pozo J, Yebra-Pimentel MT, Porta A, Fonseca E. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:54–57. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skin reaction to adalimumab. Beuthien W, Mellinghoff HU, von Kempis J. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1690–1692. doi: 10.1002/art.20155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Psoriatic lesions induced by antitumour necrosis factor-alpha treatment: two cases. Dereure O, Guillot B, Jorgensen C, Cohen JD, Combes B, Guilhou JJ. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:506–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unexpected new onset or ecacerbation of psoriasis in treatment of active anlylosing spondylitis with TNF-alpha blocking agents: four case reports. Haibel H. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1574231875324279808 Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:405. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Psoriasis induced by anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: a paradoxical adverse reaction. Sfikakis PP, Iliopoulos A, Elezoglou A, Kittas C, Stratigos A. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2513–2518. doi: 10.1002/art.21233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Unexpected onset of psoriasis during infliximab treatment: comment on the article by Beuthien et al. Grinblat B, Scheinberg M. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1333–1334. doi: 10.1002/art.20954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Infliximab can precipitate as well as worsen palmoplantar pustulosis: possible linkage to the expression of tumour necrosis factor-alpha in the normal palmar eccrine sweat duct? Michaëlsson G, Kajermo U, Michaëlsson A, Hagforsen E. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1243–1244. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pustular skin lesions in patients treated with infliximab: report of two cases. Starmans-Kool MJ, Peeters HR, Houben HH. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00296-004-0567-5. Rheumatol Int. 2005;25:550–552. doi: 10.1007/s00296-004-0567-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Onset of flexural psoriasis during infliximab treatment for Crohn's disease. Peramiquel L, Puig L, Dalmau J, Ricart E, Roe E, Alomar A. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:713–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.01882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pustulose palmaire et plantaire chez une patiente traitee par adalimumab [Article in French] Zarinitsky C: Pustulose palmaire et plantaire chez une patiente traitee par adalimumab. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1570291226422164352 RevRhum. 2005;72:1195. [Google Scholar]

- 29.New onset or exacerbation of psoriatic skin lesions in patients with definite rheumatoid arthritis receiving tumour necrosis factor alpha antagonists. Kary S, Worm M, Audring H, et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:405–407. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.037424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Infliximab associated new-onset psoriasis. Adams DR, Buckel T, Sceppa JA. https://europepmc.org/article/med/16485887. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:178–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Development of new-onset psoriasis while on anti-TNFalpha treatment. Matthews C, Rogers S, FitzGerald O. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1529–1530. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.040576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flare and change of psoriasis morphology during the course of treatment with tumour necrosis factor blockers. Goiriz R, Daudén E, Pérez-Gala S, Guhl G, García-Díez A. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:176–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced psoriasis. Sari I, Akar S, Birlik M, Sis B, Onen F, Akkoc N. https://www.jrheum.org/content/33/7/1411.short. Journal of rheumatology. 2006;33:1411–1414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced psoriasiform eruptions: three further cases and current overview. Pirard D, Arco D, Debrouckere V, Heenen M. Dermatology. 2006;213:182–186. doi: 10.1159/000095033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Psoriasis onset during infliximab treatment: description of two cases. Volpe A, Caramaschi P, Carletto A, Pieropan S, Bambara LM, Biasi D. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00296-006-0144-1. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:1158–1160. doi: 10.1007/s00296-006-0144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Psoriasis inducida por infliximab: unhecho paradójico [Article in Spanish] GONZÁLEZ-LÓPEZ M, Blanco-Alonso R, Yánez-Díaz S. https://medes.com/publication/31712. Med Clin (Barc. 2006;127:316. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(06)72243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tumor necrosis factor-a antagonist-induced psoriasis: yet another paradox in medicine. Aslanidis S, Pyrpasopoulou A, Douma S, Triantafyllou A. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10067-007-0789-5. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:377–380. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0789-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.New-onset psoriatic palmoplantaris pustulosis following infliximab therapy: a class effect? Roux CH, Brocq O, Leccia N, et al. https://www.jrheum.org/content/34/2/434.tab-article-info. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:434–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cutaneous adverse reaction to infliximab: report of psoriasis developing in 3 patients. Severs GA, Lawlor TH, Purcell SM, Adler DJ, Thompson R. https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/Document/September-2017/080030231.pdf. Cutis. 2007;80:231–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Onset of psoriasis during treatment with TNF-{alpha} antagonists: a report of 3 cases. Ubriani R, Van Voorhees AS. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:270–272. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor-induced psoriasis or psoriasiform exanthemata: first 120 cases from the literature including a series of six new patients. Wollina U, Hansel G, Koch A, Schönlebe J, Köstler E, Haroske G. https://link.springer.com/article/10.2165/00128071-200809010-00001. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:1–14. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200809010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Psoriasis induced by infliximab in a patient suffering from Crohn's disease. Manni E, Barachini P. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2009;22:841–844. doi: 10.1177/039463200902200331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Psoriasiform eruption associated with alopecia areata during infliximab therapy. Nakagomi D, Harada K, Yagasaki A, Kawamura T, Shibagaki N, Shimada S. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:923–924. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.03127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Efficacy of cyclosporine in the treatment of a case of infliximab-induced erythrodermic psoriasis. Bruzzese V, Pepe J. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2009;22:235–238. doi: 10.1177/039463200902200126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andrews ID, Schlauder SM, Gottlieb AB. Psoriasis Forum. 16a. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications Sage CA; 2010. Psoriasiform eruption following the treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis with infliximab; pp. 64–66. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Exacerbation of psoriatic skin lesion followed by TNF-alpha antagonist treatment. Oh JM, Koh EM, Kim H, et al. J Korean Rheum Assoc. 2010;17:200–204. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anti-TNF-associated palmoplantar pustulosis. Pyrpasopoulou A, Chatzimichailidou S, Simoulidou E, Aslanidis S. J Clin Rheumatol. 2010;16:138–139. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181d59511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Onset of palmoplantar pustular psoriasis while on adalimumab for psoriatic arthritis: a 'class effect' of TNF-alpha antagonists or simply an anti-psoriatic treatment adverse reaction? Rallis E, Korfitis C, Stavropoulou E, Papaconstantis M. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:3–5. doi: 10.3109/09546630902882089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Behçet's syndrome treated with infliximab, which caused a palmoplantar pustulosis, subsequently maintained on low-dose etanercept. Tresh A, Smith VH, Parslew RA. Libyan J Med. 2012;7 doi: 10.3402/ljm.v7i0.19139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Development of diffuse alopecia with psoriasis-like eruptions during administration of infliximab for Crohn's disease. Kawashima K, Ishihara S, Yamamoto A, Ohno Y, Fukuda K, Onishi K, Kinoshita Y. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:0–4. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Infliximab-associated psoriasis in children with Crohn's disease may require withdrawal of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Broge T, Nguyen N, Sacks A, Davis M. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:0–7. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182802c93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Infliximab: paradoxical psoriasis scalp eruption with alopecia: case report. Peinado C. https://www.proquest.com/openview/3eeeed18eada338ab68455bf49f8d839/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=43703 React Wkly. 2015;1557:126–127. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Successful treatment of paradoxical psoriasis with IL 17 inhibition. Güleç GG, Aktaş İ, Ünlü Özkan F, Yurt N, Arıkan EE. Bosphorus Med J. 2020;7:34–37. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paradoxically Psoriasis, developed in a patient using adalimumab for ankylosing spondylitis: Case report. İrkin S, Çelik NÇ, Karakaş B, Karataş B, Şahin A. Cumhur Medical J. 2021;43:177–181. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of hidradenitis suppurativa patients with paradoxical psoriasiform reactions following treatment with adalimumab. Kanelleas A, Efthymiou O, Routsi E, et al. Skin Appendage Disord. 2022;8:415–418. doi: 10.1159/000524174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Psoriasis induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist therapy: case series and literature overview. Sarpel T, Başaran S, Akçam FD, Günaştı S, Denli Y. Arch Rheumatol. 2010;25:91–94. [Google Scholar]

- 57.TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis: proposed algorithm for treatment and management. Li SJ, Perez-Chada LM, Merola JF. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2018;4:70–80. doi: 10.1177/2475530318810851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pathogenesis of paradoxical reactions associated with targeted biologic agents for inflammatory skin diseases. Miyagawa F. Biomedicines. 2022;10:1485. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10071485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paradoxical psoriasis in a large cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease receiving treatment with anti-TNF alpha: 5-year follow-up study. Pugliese D, Guidi L, Ferraro PM, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:880–888. doi: 10.1111/apt.13352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Induction and exacerbation of psoriasis with TNF-blockade therapy: a review and analysis of 127 cases. Ko JM, Gottlieb AB, Kerbleski JF. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009;20:100–108. doi: 10.1080/09546630802441234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Infliximab approved for use in Crohn's disease: a report on the FDA GI Advisory Committee conference. Kornbluth A. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1998;4:328–329. doi: 10.1002/ibd.3780040415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adalimumab: in Crohn's disease. Plosker GL, Lyseng-Williamson KA. https://link.springer.com/article/10.2165/00063030-200721020-00007. BioDrugs. 2007;21:125–132. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200721020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Infliximab paradoxical psoriasis in a cohort of children with inflammatory bowel disease. Courbette O, Aupiais C, Viala J, et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019;69:189–193. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]