Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the risk of Long COVID by socioeconomic deprivation and to further examine the inequality by sex and occupation.

Design

We conducted a retrospective population-based cohort study using data from the ONS COVID-19 Infection Survey between 26 April 2020 and 31 January 2022. This is the largest nationally representative survey of COVID-19 in the UK with longitudinal data on occupation, COVID-19 exposure and Long COVID.

Setting

Community-based survey in the UK.

Participants

A total of 201,799 participants aged 16 to 64 years and with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.

Main outcome measures

The risk of Long COVID at least 4 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection by index of multiple deprivation (IMD) and the modifying effects of socioeconomic deprivation by sex and occupation.

Results

Nearly 10% (n = 19,315) of participants reported having Long COVID. Multivariable logistic regression models, adjusted for a range of variables (demographic, co-morbidity and time), showed that participants in the most deprived decile had a higher risk of Long COVID (11.4% vs. 8.2%; adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 1.46; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.34, 1.59) compared to the least deprived decile. Significantly higher inequalities (most vs. least deprived decile) in Long COVID existed in healthcare and patient-facing roles (aOR: 1.76; 95% CI: 1.27, 2.44), in the education sector (aOR: 1.68; 95% CI: 1.31, 2.16) and in women (aOR: 1.56; 95% CI: 1.40, 1.73) than men (aOR: 1.32; 95% CI: 1.15, 1.51).

Conclusions

This study provides insights into the heterogeneous degree of inequality in Long COVID by deprivation, sex and occupation. These findings will help inform public health policies and interventions in incorporating a social justice and health inequality lens.

Keywords: Long COVID, socioeconomic inequality, index of multiple deprivation, sex, occupation

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an unprecedented public health crisis globally.1,2 Emerging evidence also suggests that COVID-19 is a complex systemic disease that can leave long-term impacts to those affected. 3 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines in the UK have included ongoing symptoms under the umbrella term of ‘Long COVID’, comprising both ‘ongoing symptomatic COVID-19’ (symptoms persisting for 4–12 weeks after acute infection) and ‘post-COVID syndrome’ (≥12 weeks after acute infection). 4 These symptoms are diverse in range and include both physical and psychological manifestations. 5

According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), an estimated 2 million people in the UK (3.1% of the population) are currently experiencing Long COVID, with 67% (1.2 million) reporting that their daily activities had been adversely affected by these symptoms. 6 The underlying mechanisms of Long COVID are still unclear 7 ; however, studies report that these symptoms can occur even after having mild or asymptomatic COVID-19. Given the extent of the long-term health risk, Long COVID has been identified as one of the priority areas for further research.

Previous studies have found significantly higher risk of COVID-19 exposure, hospitalisation and mortality in the elderly, in ethnic minority populations, in people living in areas of higher deprivation, and in healthcare and frontline workers.8–11 The disproportionate impact of the pandemic on people living in deprived areas may partly be due to having greater concentration of minority ethnic groups, higher prevalence of chronic conditions, occupational exposure, heavy reliance on public transport, living in crowded or multigenerational households and having limited access to healthcare. Occupation is particularly important because workplace setting can modify exposure risk (e.g. a higher exposure risk for public-facing roles) as well as the effect of the exposure on various COVID-19-related outcomes. 12

Such findings of differential exposure and consequently higher severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in certain vulnerable groups warrant the need to investigate whether such associations also exist in cases of Long COVID. Although sociodemographic and occupational inequality in Long COVID is currently largely unexplored, understanding this is highly relevant in terms of assessing any unequal impact of the pandemic and adopting targeted public health measures. 13

Therefore, we undertook a study to estimate the risk of Long COVID by socioeconomic deprivation, independently of other potentially important predictors of Long COVID. We further examined the socioeconomic differentials in Long COVID by sex and occupation.

Methods

Data source

We used data from the COVID-19 infection survey (CIS) (DOI: 10.57906/r47r-1735). The CIS, conducted by the ONS and the University of Oxford, is a nation-wide longitudinal survey monitoring SARS-CoV-2 infection and immunity response in the UK. 14 Private households were randomly selected, and the results of nose and throat swabs by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing and blood samples by antibody testing (conducted by CIS or elsewhere, i.e. general practices) were collected at regular intervals. Participants also provided their demographic information (age, sex and ethnicity), occupation and presence of long-term health conditions at each survey visit. Since 3 February 2021, the ONS included a section in the survey questionnaire pertaining to Long COVID symptoms and their severity.

The detailed protocol and questionnaires of CIS are available online.15,16

Study population

The data for this analysis were collected by the CIS from 26 April 2020 to 31 January 2022. Participants were eligible for analysis if they were aged between 16 and 64 years at the first visit to reflect the working age population in the UK. 17 We restricted the analysis to survey participants who had an acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. Participants were excluded if they did not participate in the survey after 3 February 2021 (date when Long COVID questions were introduced in the survey) or if they did not participate at least 4 weeks after their date of first infection.

Participants were regarded as having Long COVID if they answered ‘yes’ to either: (1) having symptoms persisting for more than 4 weeks after their first SARS-CoV-2 infection which could not be explained by something else; or (2) having Long COVID symptoms that affected their day-to-day activities; or (3) having any specific Long COVID symptoms (Supplementary Figure S1).

COVID-19 cases were defined using both self-reported and ONS-conducted test results. We defined the first SARS-CoV-2 infection date (index date) as the earliest of the following: (1) date of first positive CIS PCR swab result; (2) date of first positive CIS blood sample result; (3) date of first positive non-CIS swab; (4) date of first positive non-CIS blood sample result; or (5) earliest date when the participant thought they had COVID-19. Participants were followed up from the index date up to the earliest of the following: (1) the first visit date when the participant reported having Long COVID; or (2) the date of last visit of the participant, if they did not report Long COVID.

The primary exposure of interest was area-level socioeconomic deprivation measured using the index of multiple deprivation (IMD), 18 the official measure of deprivation in the UK. IMD was grouped into deciles where decile 1 represents the most deprived 10% of small areas and decile 10 represents the least deprived 10%.

Age was estimated from the participants’ responses during the first survey visit. Ethnicity was categorised as White or non-White due to small strata after further stratification (e.g. by IMD deciles, sex, countries). Ongoing long-term conditions (if the participants reported having any conditions excluding COVID-19-related symptoms that lasted or expected to last for ≥1 year), household size, 19 urban or rural residence, country, and calendar time of the index date (expressed as quarter of the year) were also included as covariates in the analysis. Household size of the participants was grouped into three categories: households of one, two, and three persons or more. We categorised participants’ occupations into four groups based on responses from each individual concerning whether their current job regularly involves in-person contact with patients or clients: (1) patient-facing healthcare workers; (2) non-patient-facing healthcare workers; (3) patient- or client-facing non-healthcare workers; and (4) others (including workers in non-patient- or client-facing role, unemployed, unknown, etc.). We had complete data on all variables except co-morbid conditions and occupation. Any missing records on the index date were imputed with the most recent valid data (Supplementary Table S1). We also excluded four occupational groups because of insufficient event counts by IMD deciles (fewer than 50) (Supplementary Table S2).

Statistical analysis

We generated descriptive statistics of demographic characteristics at the index date for the overall cohort, and for IMD decile 1 (most deprived) and decile 10 (least deprived).

We used multivariable logistic regression models to estimate the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) of experiencing Long COVID by IMD deciles (using the least deprived group as the reference). We adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, urban or rural location, co-morbid conditions, household size, healthcare and patient/client facing nature of the job, quarter of the year and country. We also included the logarithm of the follow-up time as an offset term. CIs were estimated using robust variance estimator.

Since the OR only provides a relative risk for the group of interest compared to the reference group, we also estimated the absolute adjusted marginal risk from the regression models. We also conducted stratified analysis by sex and occupation.

Sensitivity analysis

As a sensitivity analysis, we conducted multilevel logistic regression model, fitting random effects at country level to allow for the clustering of the data, adjusting for the same covariates. Since each of the four countries in the UK have used slightly different methods for measuring deprivation, we conducted another sensitivity analysis using participants residing in England. We carried out an additional sensitivity analysis excluding self-reported data to define the COVID-19 infection date.

All data management and statistical analyses were performed using Python v.3.6 and Stata MP v.16.

Results

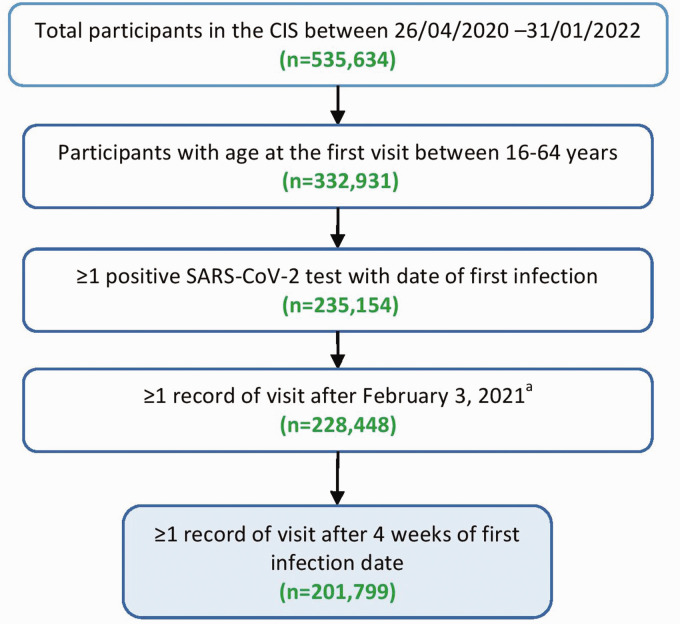

During the study period, 201,799 participants were eligible for our analysis (Figure 1). Included and excluded participants had comparable distributions of IMD (Supplementary Table S3).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for the analysis of Long COVID symptoms.a3 February 2021 was the date the Long COVID questionnaire was introduced in the ONS CIS survey.

Participants had a median follow-up of 214 days (interquartile range (IQR): 147–331 days) with a median number of 6 (IQR: 3–9) follow-up visits. Compared to the least deprived, participants in the most deprived decile had a lower mean age (43.8 vs. 46.3 years), lower proportion of men (42.7% vs. 45.1%), lower proportion from the White ethnic population (90.7% vs. 94.7%), higher proportion from urban areas (97.1% vs. 82.8%), from one-person households (21.9% vs. 8.5%) and a higher prevalence of co-morbid conditions (42.2% vs. 23.1%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the cohort.

| Characteristics | IMD1 (most deprived) (N = 9,483) | IMD10 (least deprived) (N = 27,113) | Overall(N = 201,799) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 43.8 (13.0) | 46.3 (12.7) | 45.1 (12.9) |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 45.0 (33.0–55.0) | 48.0 (39.0–57.0) | 47.0 (36.0–56.0) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 4048 (42.7) | 12,234 (45.1) | 89,116 (44.2) |

| Female | 5435 (57.3) | 14,879 (54.9) | 112,683 (55.8) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 8600 (90.7) | 25,679 (94.7) | 186,547 (92.4) |

| Non-White | 883 (9.3) | 1434 (5.3) | 15,252 (7.6) |

| Rural/urban, n (%) | |||

| Urban | 9211 (97.1) | 22,462 (82.8) | 160,623 (79.6) |

| Rural | 272 (2.9) | 4651 (17.2) | 41,176 (20.4) |

| Household size in persons, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 2081 (21.9) | 2299 (8.5) | 26,539 (13.2) |

| 2 | 3252 (34.3) | 8968 (33.1) | 74,264 (36.8) |

| ≥3 | 4150 (43.8) | 15,846 (58.4) | 100,996 (50.0) |

| Any co-morbid conditions, n (%) | |||

| No | 5484 (57.8) | 20,855 (76.9) | 145,886 (72.3) |

| Yes | 3999 (42.2) | 6258 (23.1) | 55,913 (27.7) |

| Country, n (%) | |||

| England | 7989 (84.2) | 22,668 (83.6) | 171,602 (85.0) |

| Scotland | 777 (8.2) | 2272 (8.4) | 15,253 (7.6) |

| Wales | 498 (5.3) | 1233 (4.5) | 9232 (4.6) |

| Northern Ireland | 219 (2.3) | 940 (3.5) | 5712 (2.8) |

| Occupational role | |||

| Non-healthcare patient/client facing | 1943 (20.5) | 5324 (19.6) | 42,013 (20.8) |

| Healthcare non-patient/client facing | 326 (3.4) | 1081 (4.0) | 7417 (3.7) |

| Healthcare patient/client facing | 624 (6.6) | 1675 (6.2) | 12,934 (6.4) |

| Other or unknown | 6590 (69.5) | 19,033 (70.2) | 139,435 (69.1) |

IMD: index of multiple deprivation; SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range.

One in 10 (9.6%; n = 19,315) participants reported having Long COVID. The prevalence of Long COVID was higher in women (n = 11,875, 11.8%) than men (n = 7440, 9.1%) and in participants residing in the most deprived decile (n = 1229, 13.0%) versus those who resided in the least deprived decile (n = 2188, 8.1%) (Supplementary Table S4). The prevalence of Long COVID by IMD and occupational groups showed similar trends (Supplementary Table S5).

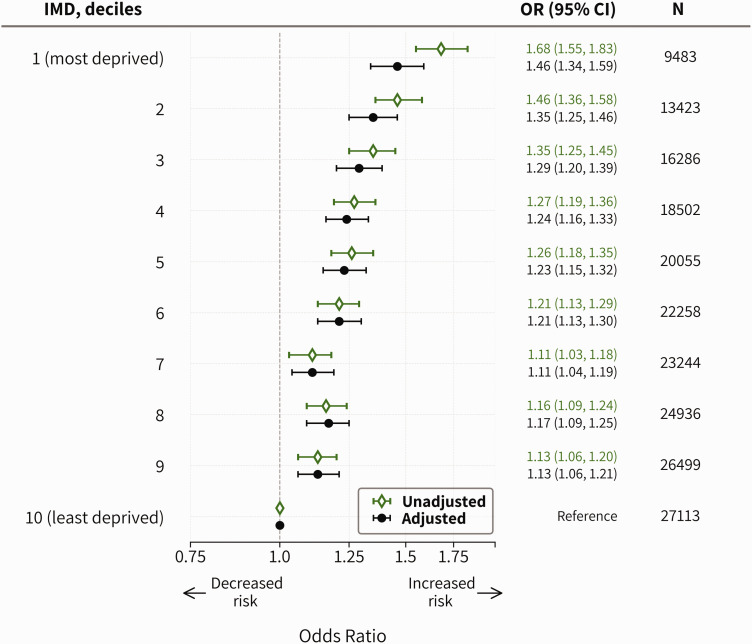

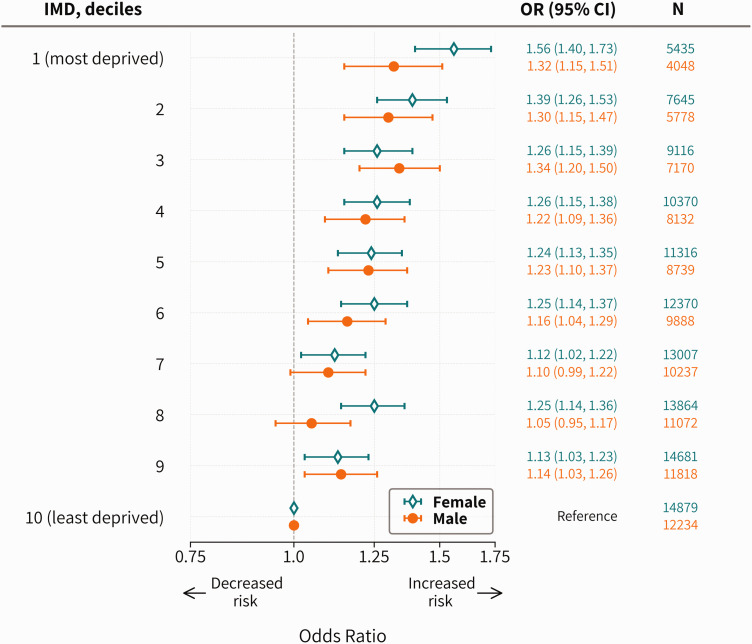

The adjusted odds of having Long COVID was greater in more deprived neighbourhoods (Figure 2). After adjusting for potential covariates, the odds of Long COVID were 46% higher (OR: 1.46; 95% CI: 1.34, 1.59) in the most deprived decile (compared to the least). These findings were robust in several sensitivity analyses (Supplementary Tables S6–S8). When stratified by sex, the results were consistent in terms of deprivation-specific trends, with a higher level of inequality (most deprived vs. least) among women (OR: 1.56; 95% CI: 1.40, 1.73) than men (OR: 1.32; 95% CI: 1.15, 1.51) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Association between deprivation and experiencing Long COVID at least 4 weeks after having COVID-19. Estimates adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, urban/rural, co-morbid conditions, household size, healthcare and patient/client facing nature of the job and country in the logistic regression model using logarithm of the follow-up time as an offset term.

Figure 3.

Association between deprivation and experiencing Long COVID at least 4 weeks after having COVID-19, stratified by sex. Estimates adjusted for age, ethnicity, urban/rural, co-morbid conditions, household size, country, quarter of the year, healthcare and patient-/client-facing nature of the job in the multivariable logistic regression model using the logarithm of the follow-up time as an offset term.

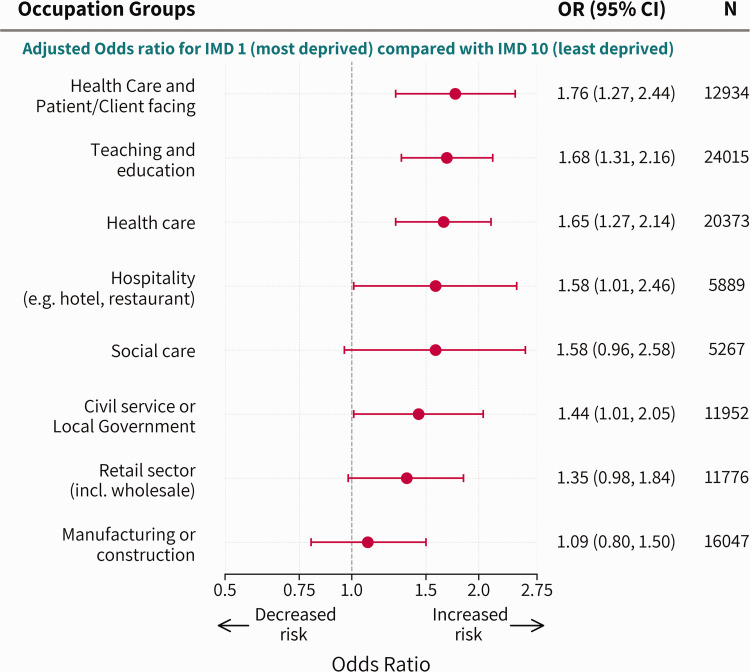

Compared to the least deprived decile, the adjusted OR of having Long COVID was higher in participants from the most deprived decile for those working in healthcare and patient-facing role (OR: 1.76; 95% CI: 1.27, 2.44), teaching and education (OR: 1.68; 95% CI: 1.31, 2.16), overall health care sector (OR: 1.65; 95% CI: 1.27, 2.14), hospitality sector (OR: 1.58; 95% CI: 1.01, 2.46) and the civil service (OR: 1.44; 95% CI: 1.01, 2.05). The occupational groups social care and the retail sector had similarly high ORs – 1.58 (95% CI: 0.96, 2.58) and 1.35 (95% CI: 0.98, 1.84), respectively, but for these smaller groups, they were not statistically significant. There was no observed association for the manufacturing or construction sector (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Association between deprivation and experiencing Long COVID at least 4 weeks after having COVID-19, stratified by occupational groups. Estimates adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, urban/rural, co-morbid conditions, household size, country and quarter of the year in the multivariable logistic regression model using the logarithm of the follow-up time as an offset term.

Overall, the adjusted prevalence of Long COVID was higher in the most deprived (11.4%; 95% CI: 10.8, 12.1) than the least deprived decile (8.2%; 95% CI: 7.9, 8.6), which increased with increasing levels of deprivation (Table 2). In men, the adjusted prevalence ranged from 7.3% (95% CI: 6.8, 7.8) in the least deprived to 9.4% (95% CI: 8.4, 10.3) in the most deprived decile. In women, the range was from 8.9% (95% CI: 8.5, 9.4) to 13.0% (95% CI: 12.1, 13.9), respectively. The risk of Long COVID in women in the least deprived decile was comparable to that in men in the most deprived decile (Table 2).

Table 2.

Proportion of participants experiencing Long COVID at least 4 weeks after having COVID-19, by IMD deciles.

| Sex stratified

b

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMD, deciles | Unadjusted% (95% CI) | Adjusted a % (95% CI) | Male% (95% CI) | Female% (95% CI) |

| 1 (most deprived) | 12.71 (12.00, 13.42) | 11.40 (10.75, 12.06) | 9.35 (8.44, 10.26) | 13.00 (12.07, 13.92) |

| 2 | 11.28 (10.72, 11.84) | 10.68 (10.14, 11.22) | 9.24 (8.47, 10.01) | 11.81 (11.06, 12.56) |

| 3 | 10.49 (9.99, 10.98) | 10.27 (9.79, 10.76) | 9.47 (8.76, 10.18) | 10.91 (10.24, 11.59) |

| 4 | 10.00 (9.54, 10.45) | 9.93 (9.48, 10.38) | 8.72 (8.08, 9.36) | 10.89 (10.26, 11.51) |

| 5 | 9.89 (9.46, 10.33) | 9.87 (9.44, 10.30) | 8.80 (8.18, 9.42) | 10.72 (10.12, 11.32) |

| 6 | 9.55 (9.14, 9.95) | 9.74 (9.32, 10.15) | 8.36 (7.79, 8.94) | 10.82 (10.24, 11.41) |

| 7 | 8.83 (8.45, 9.21) | 9.01 (8.62, 9.40) | 7.97 (7.42, 8.52) | 9.84 (9.29, 10.38) |

| 8 | 9.21 (8.83, 9.58) | 9.41 (9.02, 9.79) | 7.66 (7.14, 8.17) | 10.80 (10.25, 11.35) |

| 9 | 8.99 (8.63, 9.35) | 9.18 (8.81, 9.54) | 8.23 (7.71, 8.75) | 9.92 (9.41, 10.43) |

| 10 (least deprived) | 8.07 (7.74, 8.41) | 8.23 (7.89, 8.57) | 7.33 (6.84, 7.81) | 8.94 (8.46, 9.42) |

aAdjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, urban/rural, comorbid conditions, household size, healthcare and patient/client facing nature of the job, quarter of the year, and country in the logistic regression model using logarithm of the follow-up time as an offset term.

bAdjusted for age, ethnicity, urban/rural, comorbid conditions, household size, healthcare and patient/client-facing nature of the job, quarter of the year, and country in the logistic regression model using logarithm of the follow-up time as an offset term.

When stratified by occupation, the absolute risk was always higher in participants in the most deprived areas than those in the least deprived areas. However, the adjusted prevalence varied substantially even when the deprivation level was the same. For example, in the most deprived decile, the prevalence ranged from 10.0% (95% CI: 7.7, 12.3) in the manufacturing or construction sector to 14.6% (95% CI: 12.1, 17.2) in the education sector. In contrast, the variability within the least deprived decile was relatively smaller, and ranged from 8.3% (95% CI: 6.1, 10.5) in the hospitality sector to 9.5% (95% CI: 8.5, 10.5) in the education sector (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted proportions of participants experiencing Long COVID at least 4 weeks after having COVID-19, by occupational groups and IMD deciles.

| Occupational groups | IMD 1 (most deprived); adjusted proportions (95% CI) | IMD 10 (least deprived); adjusted proportions (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Teaching and education | 14.64 (12.11, 17.18) | 9.48 (8.47, 10.48) |

| Healthcare and patient/client facing | 13.94 (11.04, 16.83) | 8.75 (7.32, 10.18) |

| Healthcare | 13.14 (10.89, 15.39) | 8.66 (7.56, 9.76) |

| Civil service or local government | 12.32 (9.32, 15.32) | 9.05 (7.56, 10.53) |

| Social care | 12.31 (8.80, 15.83) | 8.36 (5.84, 10.87) |

| Hospitality | 12.24 (8.91, 15.58) | 8.28 (6.06, 10.50) |

| Retail sector | 12.04 (9.71, 14.38) | 9.36 (7.67, 11.06) |

| Manufacturing or construction | 10.02 (7.70, 12.34) | 9.27 (7.95, 10.58) |

Adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, urban/rural, comorbid conditions, household size, quarter of the year, and country in the logistic regression model using logarithm of the follow-up time as an offset term. IMD: index of multiple deprivation.

Discussion

In this study, using a nationally representative community-based survey of over 200,000 working-age adults, we found that the risk of Long COVID is strongly associated with area-level deprivation. We also found that the odds of Long COVID are 46% higher on average for participants from the most deprived areas compared to those in the least deprived areas. Our findings are robust after controlling for demographic factors, household size, calendar time, co-morbidity and follow-up duration. The probability of Long COVID increased in an almost dose–response fashion with increasing levels of deprivation, both in men and women. Women also exhibited an elevated risk of Long COVID, compared to men across all the IMD deciles. We also found that these associations varied widely by occupation. Those living in the most deprived areas and working in the healthcare (both patient-facing and non-patient-facing) and education sectors had the highest risk of Long COVID compared to the least deprived decile, while no significant association was observed in the manufacturing or construction sector.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify the association between Long COVID and socioeconomic status and occupation. Previous research found that female sex, age, smoking, obesity, number and severity of COVID-19 symptoms, and co-morbidities are strong predictors of Long COVID.20–25 A recent study 21 found no significant variation within different socioeconomic groups, while another 22 reported that deprivation was associated with Long COVID. Although certain occupational groups, especially frontline and essential workers, have been unequally affected by the COVID-19 pandemic,9,26 studies on Long COVID and occupation are sparse. One recent study reported that healthcare workers had a higher probability of having Long COVID. However, none of the prior studies investigated Long COVID among a wide range of occupational groups and explored the intersectional inequalities (sex, deprivation and occupation) as this study did. Our findings are not directly comparable in the context of COVID-19 because no previous study has conducted such analysis. However, our results are consistent with pre-pandemic research on other health conditions suggesting that workers with lower socioeconomic status have poorer health outcomes and higher premature mortality than those with higher socioeconomic position but a similar occupation. 27 Previous evidence, together with the results from this study, suggest that inequalities in Long COVID cannot be viewed in isolation without considering the role of occupation in a gender-blind manner.

This study indicates the need for a diverse range of public health interventions after recovery from COVID (treatment and/or rehabilitation) across multiple intersecting social dimensions as well as data for reducing disproportionate impact on these populations in any future waves of the pandemic. Hence, our findings highlight the necessity of managing the post-recovery of COVID-19 with a health equity lens. These include assessing the differentials in Long COVID diagnosis, health-seeking behaviour and follow-up after recovery across the intersections of sex, occupation and socioeconomic circumstances of people. The assessment will help inform health policy in identifying the most vulnerable sub-groups of populations so that more focused efforts are given, and proportional allocation of resources are implemented to facilitate the reduction of health inequalities.

Most studies on health inequality have predominantly taken unitary approaches (focusing on sex, ethnicity or deprivation separately) and rarely explored the impact of intersectional inequality on population health. 28 However, the inequalities shown in this study show that such approach can provide more precise identification of risks and be relevant to other diseases and beyond the pandemic.

Strengths and limitations

The study has several key strengths. CIS is the largest nationally representative community-based longitudinal survey of COVID-19 in the UK. The survey provides rich, contemporaneous and longitudinal data on socioeconomic factors, occupation, health status, demographics, COVID-19 exposure and Long COVID. The survey conducted COVID-19 tests at each visit and captured Long COVID data among participants who would not have been tested due to lack of symptoms. Thus, our study examined Long COVID in both asymptomatic and symptomatic COVID-19 patients. We also adjusted for a range of covariates in the model to estimate the independent effects of the IMD on the respective outcomes.

However, our study has some limitations. First, IMD is an ecological measure; therefore, these findings may not be interpreted at an individual level. Second, Long COVID symptoms are diverse 5 and our study may not have captured the full range of symptoms. However, the 21 specific symptoms of Long COVID included in the survey questionnaire are selected based on a comprehensive review of the existing evidence and encompass the most prevalent symptoms reported by patients.23,29 Third, Long COVID symptoms and co-morbidities were self-reported. Therefore, it is possible that some of the reported symptoms may not be directly caused by COVID-19. In principle, it would be ideal to have the self-reported COVID-19 and Long COVID status validated using healthcare records. However, previous research showed that Long COVID symptoms were underreported in primary care, possibly due to limited use of primary health care during the pandemic. Our definition is also consistent with previous studies16,30 and ONS reports. 6 Fourth, as this is an observational analysis, a causal relationship between socioeconomic deprivation and the risks of Long COVID cannot be established.

Our research also could not examine the time to remission of Long COVID symptoms due to lack of granular longer term follow-up data. Future studies may examine if the time to remission varies by occupation and deprivation. Future research could also explore additional set of symptoms that are yet to be reported and recognised as Long COVID symptoms.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that people from the most socioeconomically deprived populations have the highest risk of Long COVID, and this inequality is independent of differences in the risk of initial infection. The level of inequality was particularly higher in participants who are female, working in healthcare and in the education sector. Future health policy recommendations should incorporate the multiple dimensions of inequality, such as sex, deprivation and occupation when considering the treatment and management of Long COVID.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jrs-10.1177_01410768231168377 for Socioeconomic inequalities of Long COVID: a retrospective population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom by Sharmin Shabnam, Cameron Razieh, Hajira Dambha-Miller, Tom Yates, Clare Gillies, Yogini V Chudasama, Manish Pareek, Amitava Banerjee, Ichiro Kawachi, Ben Lacey, Eva JA Morris, Martin White, Francesco Zaccardi, Kamlesh Khunti and Nazrul Islam in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine

Guarantor: NI.

Contributorship: NI and KK conceived and designed the study, obtained the funding, developed the statistical methodology and managed and coordinated research activity. SS and NI carried out the data preparation, analyses and data visualisation. SS drafted the first version of the article. NI contributed significant edits and input for the draft article. All authors contributed to reviewing the article and interpreting the findings. All authors have approved the final published version.

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to Dr. Vahé Nafilyan and Daniel Ayoubkhani from the ONS for their contributions to the analysis and very helpful feedback on earlier versions of the article.

Provenance: Not commissioned; peer reviewed by Julie Morris.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this report are solely the authors' and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the organisations/entities the authors are employed by and/or affiliated with. This work was produced using statistical data from the ONS which is Crown Copyright. The use of the ONS statistical data in this work does not imply the endorsement of the ONS in relation to the interpretation or analysis of the statistical data. This work uses research datasets which may not exactly reproduce National Statistics aggregates.

ORCID iDs: Amitava Banerjee https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8741-3411

Nazrul Islam https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3982-4325

Declarations

Competing Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: KK is chair of the ethnicity subgroup of the UK Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) and is a member of SAGE. KK, SS, TY, FZ, CG, YC, CR, MP are supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration East Midlands (ARC EM) and the NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). MW is supported by Medical Research Council funding for the MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge (grant number MC/UU/00006/7). Other authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was funded by the ONS. Project number: 2002569, Ref: PU-22-0205(a).

Ethics approval

The ONS CIS was approved by the South-Central Berkshire B Research Ethics Committee (Ethics Ref: 20/SC/0195). The study was assessed using the National Statistician's Data Ethics Advisory Committee (NSDEC) ethics self-assessment tool, and the committee confirmed that no further ethical consideration was required.

Data availability statement

The data from the Office for National Statistics CIS can be accessed only by ONS accredited researchers through the Secure Research Service. Researchers can apply for accreditation through the Research Accreditation Service and will need approval to access CIS data. For further details see: https://www.ons.gov.uk/aboutus/whatwedo/statistics/requestingstatistics/secureresearchservice. Analytic code is available at: https://github.com/shabnam-shbd/Socioeconomic-inequalities-of-Long-COVID

Supplemental material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Miller IF, Becker AD, Grenfell BT, Metcalf CJE. Disease and healthcare burden of COVID-19 in the United States. Nat Med 2020; 26: 1212–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Islam N, Shkolnikov VM, Acosta RJ, Klimkin I, Kawachi I, Irizarry RA, et al. Excess deaths associated with covid-19 pandemic in 2020: age and sex disaggregated time series analysis in 29 high income countries. BMJ 2021; 373: n1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, Mariette X. Systemic and organ-specific immune-related manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2021; 17: 315–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venkatesan P. NICE guideline on long COVID. Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9: 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez-Leon S, Wegman-Ostrosky T, Perelman C, Sepulveda R, Rebolledo PA, Cuapio A, et al. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scient Rep 2021; 11: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK – Office for National Statistics. See www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/prevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronaviruscovid19infectionintheuk/1june2022 (last checked 9 June 2022).

- 7.Desai AD, Lavelle M, Boursiquot BC, Wan EY. Long-term complications of COVID-19. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2022; 322: C1–C11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kontopantelis E, Mamas MA, Webb RT, Castro A, Rutter MK, Gale CP, et al. Excess years of life lost to COVID-19 and other causes of death by sex, neighbourhood deprivation, and region in England and Wales during 2020: a registry-based study. PLoS Med 2022; 19: e1003904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nafilyan V, Pawelek P, Ayoubkhani D, Rhodes S, Pembrey L, Matz M, et al. Occupation and COVID-19 mortality in England: a national linked data study of 14.3 million adults. Occup Environ Med 2022; 79: 433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Razieh C, Zaccardi F, Gillies CL, Gillies CL, Chudasama YV, Rowlands A, et al. Ethnic minorities and COVID-19: examining whether excess risk is mediated through deprivation. Eur J Public Health 2021; 31: 630–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Islam N, Khunti K, Dambha-Miller H, Kawachi I, Marmot M. COVID-19 mortality: a complex interplay of sex, gender and ethnicity. Eur J Public Health 2020; 30: 847–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen LH, Drew DA, Graham MS, Joshi AD, Guo C-G, Ma W, et al. Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2020; 5: e475–e483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marmot M. Health equity in England: the Marmot review 10 years on. BMJ 2020; 368: m693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.COVID-19 Infection Survey – Office for National Statistics. See www.ons.gov.uk/surveys/informationforhouseholdsandindividuals/householdandindividualsurveys/covid19infectionsurvey (last checked 28 June 2022).

- 15.Protocol and information sheets – Nuffield Department of Medicine. See www.ndm.ox.ac.uk/covid-19/covid-19-infection-survey/protocol-and-information-sheets (last checked 9 June 2022).

- 16.Ayoubkhani D, Bermingham C, Pouwels KB, Glickman M, Nafilyan V, Zaccardi F, et al. Trajectory of long covid symptoms after covid-19 vaccination: community based cohort study. BMJ 2022; 377: e069676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Working age population – GOV.UK Ethnicity facts and figures. See www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/demographics/working-age-population/latest (last checked 28 June 2022).

- 18.Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection Survey, characteristics of people testing positive for COVID-19, UK – Office for National Statistics. See www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/coronaviruscovid19infectionsurveycharacteristicsofpeopletestingpositiveforcovid19uk/20july2022 (last checked 19 August 2022).

- 19.Gillies CL, Rowlands AV, Razieh C, Nafilyan V, Chudasama Y, Islam N, et al. Association between household size and COVID-19: a UK Biobank observational study. J R Soc Med 2022; 115: 138–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bai F, Tomasoni D, Falcinella C, Barbanotti D, Castoldi R, Mulè G, et al. Female gender is associated with long COVID syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2022; 28: 611.e9–611.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sudre CH, Murray B, Varsavsky T, Graham MS, Penfold RS, Bowyer RC, et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med 2021; 27: 626–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitaker M, Elliott J, Chadeau-Hyam M, Riley S, Darzi A, Cooke G, et al. Persistent COVID-19 symptoms in a community study of 606,434 people in England. Nat Commun 2022; 13: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ziauddeen N, Gurdasani D, O’Hara ME, Hastie C, Roderick P, Yao G, et al. Characteristics and impact of Long Covid: findings from an online survey. PLoS One 2022; 17: e0264331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson EJ, Williams DM, Walker AJ, Mitchell RE, Niedzwiedz CL, Yang TC, et al. Long COVID burden and risk factors in 10 UK longitudinal studies and electronic health records. Nat Commun 2022; 13: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamal M, Abo Omirah M, Hussein A, Saeed H. Assessment and characterisation of post-COVID-19 manifestations. Int J Clin Pract 2021; 75: e13746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mutambudzi M, Niedwiedz C, Macdonald EB, Leyland A, Mair F, Anderson J, et al. Occupation and risk of severe COVID-19: prospective cohort study of 120 075 UK Biobank participants. Occup Environ Med 2021; 78: 307–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewer D, Jayatunga W, Aldridge RW, Edge C, Marmot M, Story A, et al. Premature mortality attributable to socioeconomic inequality in England between 2003 and 2018: an observational study. Lancet Public Health 2020; 5: e33–e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kapilashrami A, Hankivsky O. Intersectionality and why it matters to global health. The Lancet 2018; 391: 2589–2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis HE, Assaf GS, McCorkell L, Wei H, Low RJ, Re'em Y, et al. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine 2021; 38: 101019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker AJ, MacKenna B, Goldacre B. Clinical coding of long COVID in English primary care: a federated analysis of 58 million patient records in situ using OpenSAFELY. Br J Gen Practice 2021; 71: 495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jrs-10.1177_01410768231168377 for Socioeconomic inequalities of Long COVID: a retrospective population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom by Sharmin Shabnam, Cameron Razieh, Hajira Dambha-Miller, Tom Yates, Clare Gillies, Yogini V Chudasama, Manish Pareek, Amitava Banerjee, Ichiro Kawachi, Ben Lacey, Eva JA Morris, Martin White, Francesco Zaccardi, Kamlesh Khunti and Nazrul Islam in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine

Data Availability Statement

The data from the Office for National Statistics CIS can be accessed only by ONS accredited researchers through the Secure Research Service. Researchers can apply for accreditation through the Research Accreditation Service and will need approval to access CIS data. For further details see: https://www.ons.gov.uk/aboutus/whatwedo/statistics/requestingstatistics/secureresearchservice. Analytic code is available at: https://github.com/shabnam-shbd/Socioeconomic-inequalities-of-Long-COVID