Abstract

Background:

Patient return-to-driving following minor hand surgery is unknown. Through daily text message surveys, we sought to determine return-to-driving after minor hand surgery and the factors that influence return-to-driving.

Methods:

One hundred five subjects undergoing minor hand surgery received daily text messaging surveys postoperatively to assess: (1) if they drove the day before and if so; (2) whether they wore a cast, sling, or splint. Additional patient-, procedure-, and driving-related data were collected.

Results:

More than half of subjects, 54 out of 105, returned to driving by the end of postoperative day #1. While patient-related factors had no effect on return-to-driving, significant differences were seen in anesthesia type, procedure laterality, driving assistance, and distance. Return-to-driving was significantly later for subjects who had general anesthetic compared to wide awake local anesthetic with no tourniquet (4 ± 4 days vs 1 ± 3 days, P = 0.020), as well as for bilateral procedures versus unilateral procedures (5 ± 5 days vs 1 ± 3 days, P = 0.046). Lack of another driver and driving on highways led to earlier return-to-driving (P = 0.040 and, P = 0.005, respectively).

Conclusions:

Most patients rapidly return to driving after minor hand surgery. Use of general anesthetic and bilateral procedures may delay return-to-driving. Confidential real-time text-based surveys can provide valuable information on postoperative return-to-driving and other patient behaviors.

Keywords: hand, anatomy, wrist, anatomy, thumb, carpal tunnel syndrome, nerve, diagnosis, outcomes, research & health outcomes, anesthesia, specialty, rehabilitation, surgery

Introduction

Physician-imposed driving restrictions after minor hand surgery are burdensome for patients, and their necessity is unknown.1-4 Presently, there is no readily available tool to determine driving fitness after hand and upper extremity surgery, causing return to driving decisions to be based on a combination of limited objective research, consensus society guidelines, and anecdotal experience.1,4-10 Postoperative pain management has evolved toward nonnarcotic pain management as the use of wide-awake local anesthetic no tourniquet (WALANT) becomes more common compared to general anesthesia (GA) for minor hand surgical procedures.11,12 The subsequent shift to nonnarcotic postoperative pain management has differing implications for postoperative driving instructions in comparison to narcotic postoperative pain medication used previously after GA procedures.11,12 Consequently, the traditional recommendations on when to safely return to driving following hand and upper extremity surgery are no longer applicable. A recent investigation by Orfield et al demonstrated that patients are safe to drive immediately after WALANT procedures, 9 but patient postoperative return-to-driving and factors that influence return-to-driving remain unknown.

Previous studies investigating driving fitness and return-to-driving after surgery have used retrospective surveys of both patients and surgeons.4,5 In one study, patients who had undergone hand surgery under local anesthesia were provided surveys to assess whether they drove themselves home after their procedure and their perception of doing so. 1 These surveys were administered retrospectively up to 5 months after surgery, introducing recall bias. Methods such as a daily text message-based survey would mitigate recall bias and allow prospective real time data collection on patient driving behavior.11,13-15 Smartphone ownership is now common in the United States, specifically within the driving age range, and smartphone owners in these age groups reported that they use their phone for texting.16,17 Several clinical research studies have achieved high contact rates and response rates when utilizing text messaging to contact patients,14,16 with some studies reporting response rates of > 94%.13,15,18,19

The healthcare system has seen progressively increased text message use in the last 2 decades. Text message surveying has been shown to be a valid and reliable instrument for data collection and analysis in research.15,19,20 In this study, we used confidential text message surveys to assess patient return-to-driving and factors that influence return-to-driving after minor hand surgery. We hypothesized that patient return-to-driving decision is affected by several factors, including patient-, procedure-, and driving-related factors.

Methods

Participants

Over a 6-month enrollment period, 105 patients (mean age 52, range 22-74) who were scheduled for endoscopic carpal tunnel release, open carpal tunnel release, trigger finger release, de Quervain’s release, or mucous cyst excision were consented and enrolled electronically. All patients were seen at a tertiary academic medical institution and were contacted, screened, and recruited for this study by clinical research assistants. Patients between the ages of 18 and 75 years old who had access to the internet, a smartphone capable of texting, and a valid driver’s license and who were self-reported regular drivers were included in the study. Patients were excluded from the study if they were taking narcotics postoperatively for any reason, unable to provide informed consent, unable to speak English fluently, and currently not driving because of illness or injury. Patient demographics were collected through daily short survey text messages and the electronic medical record (EMR) (Table 1). Oversight of this study was provided by the institutional review board.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics.

| Patient Age | 53 ± 23 | ||

| Sex | Employed | ||

| Female | 63.8% | Yes | 63.8% |

| Male | 36.2% | No | 36.2% |

| Race | College degree | ||

| Black | 6.7% | Yes | 55.2% |

| White | 91.4% | No | 44.8% |

| More than one race | 1.9% | ||

| Ethnicity | Income > $50,000 | ||

| Latino | 0% | Yes | 70.5% |

| Not Latino | 100% | No | 29.5% |

| Community | Operative hand(s) | ||

| Metro | 85.7% | Left | 42.0% |

| Nonmetro—Urban | 11.4% | Right | 48.0% |

| Nonmetro—Rural | 2.9% | Bilateral | 10.0% |

| Type of procedures | Smoking | ||

| Trigger finger release | 21.9% | Yes | 12.4% |

| Open CTR | 25.7% | No | 87.6% |

| Endoscopic CTR | 12.4% | Diabetes | |

| De Quervain’s release | 38.0% | Yes | 23.8% |

| Cyst excision | 8.6% | No | 76.2% |

| Multiple procedures | 27.6% |

Note. CTR, carpal tunnel release procedures; IQR, interquartile range. Continuous variables are reported as medians ± IQR and categorical variables are reported as percentages. Community is defined as metro (250,000 to 1 million population), nonmetro—urban (2500 to 19,999 population), or nonmetro—rural (fewer than 2500 population). Multiple procedures indicates a minor hand procedure (trigger finger release, open CTR, endoscopic CTR, de Quervain’s release, or cyst excision) that included concomitant procedure(s).

Survey Methods

Subjects received daily short survey text messages for 2 weeks following their minor hand procedures, followed by weekly short survey text messages (Figure 1). A final survey was texted after subjects reported return-to-driving day without a cast, splint, or sling. Subject responses were limited to “Y” for yes or “N” for no to the daily, weekly, and follow-up questions as well as the 7-question final survey (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Screening, enrollment, and text survey flow chart. Text message survey responses are indicated by “Y” for yes and “N” for no.

Table 2.

Text Message Survey Questions.

| Daily question | “Did you drive yesterday?” |

| Weekly question | “Did you drive in the past 7 days?” |

| Follow-up question | “Did you wear a cast, splint, or sling?” |

| Final survey questions | “Did you receive any return-to-driving instructions from your care team?” |

| “Did you take any prescription pain medication?” | |

| “Did you drive on the interstate or the highway?” | |

| “Did you have someone who could reliably drive you after your surgery?” | |

| “Are you employed?” | |

| “Do you have a college degree?” | |

| “Is your household income above $50,000?” |

Subject community was defined as metro (250,000 to 1 million population), nonmetro—urban (2500 to 19,999 population), and nonmetro—rural (fewer than 2500 population). Community was determined through United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service by finding county via subject zip code. 21 Study data were collected and managed using a secure, web-based software platform Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap, version 9.8.4).22,23

Text Messaging Integration With REDCap

This project used REDCap with a Twilio plugin integrated function. Twilio is an application that enables a research study to make and receive voice calls and short message service (SMS) text messages, both to and from survey respondents. Questions are asked successively as an SMS text message conversation thread; subjects respond with alpha-numeric text. Survey as SMS text conversation is not encrypted communication, and protected health information as defined by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) was not collected via this method.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were calculated on the demographic variables to provide a description of the patients included in the study (Table 1). Generalized linear modeling (GLM) with a log link and negative binomial distribution was performed with input from the 105 subjects that continued the study to completion to assess the influence of patient-, procedure-, and driving-related factors on return-to-driving (Supplemental Table S1, Table 3). Variables in the final GLM include patient age, sex, operative hand(s), anesthesia, provided driving instructions, prescribed pain medication, drove on highway, had another driver, employment, college degree, and income. Post-hoc analysis was used to determine statistical significance in return-to-driving between left- versus right-sided procedures. Continuous variables are reported as medians ± interquartile range and categorical variables are reported as percentages. Full detailed methods and analysis are contained in Supplemental Material and Supplemental Table S3. SAS Enterprise Guide statistical software was used for data analysis.

Table 3.

Factors That Influence Return-to-Driving Following Minor Hand Surgery.

| Variables | P value |

|---|---|

| Patient age | 0.5243 |

| Male vs female | 0.0529 |

| Unilateral vs bilateral | *0.0458 |

| WALANT versus GA | *0.0196 |

| Provided driving instructions | 0.7358 |

| Prescription pain medication | 0.7685 |

| Drive on highway | *0.0045 |

| Someone to drive you | *0.0402 |

| Employed | 0.3103 |

| College degree | 0.9922 |

| Household income Above/below $50,000 |

0.2640 |

Note. WALANT, wide-awake local anesthetic no tourniquet; GA, general anesthesia.

Findings of < 0.05 are considered significant.

Results

In this study, 544 subjects were screened, 134 subjects were enrolled, and 105 subjects continued the study to completion with the removal of 29 subjects (21.6%) from data analysis either due to postop exclusion or incomplete survey response (Figure 1). Our study sample ultimately consisted of 105 subjects, including 67 females (63.8%) and 38 males (36.2%), presenting at an average age of 52, range 22 to 74 years (Table 1). The study sample was 91.4% White (96 of 105), 6.7% Black (7 of 105), and 1.9% more than one race (2 of 105). There were 5 minor hand surgical procedures in this study: endoscopic carpal tunnel release (13 of 105, 12.4%), open carpal tunnel release (27 of 105, 25.7%), trigger finger release (23 of 105, 21.9%), DeQuervain’s release (40 of 105, 38.0%), and mucous cyst excision (9 of 105, 8.6%). Overall, 27.6% of subjects underwent concomitant minor hand procedures (29 of 105). In all, 12.4% of subjects were active smokers (13 of 105) and 23.8% were diabetic (25 of 105).

About a third of subjects (31 of 105, 29.5%) returned to driving the day of surgery, about half of subjects (54 of 105, 51.4%) returned to driving by postoperative day #1, more than 3-quarters of subjects (80 of 105, 76.2%) returned to driving by postoperative day #4, and most subjects (96 of 105, 91.4%) returned to driving by postoperative day #7 (Figure 2). Overall, 34% of subjects reported that they returned to driving while wearing a cast, splint, or sling. The type of anesthesia, operative hand(s), having another driver available, and driving on the highway were statistically significant factors on return-to-driving when adjusting for other variables for confounding in the GLM (Table 3). Other procedure-, driving-, and patient-related factors, including socioeconomic- and health-related variables, did not significantly predict return-to-driving.

Figure 2.

Distribution of patient-reported return-to-driving. Histogram demonstrates distribution of when patients return to driving following minor hand surgery (trigger finger release, open carpal tunnel release, endoscopic carpal tunnel release, de Quervain’s release, or cyst excision).

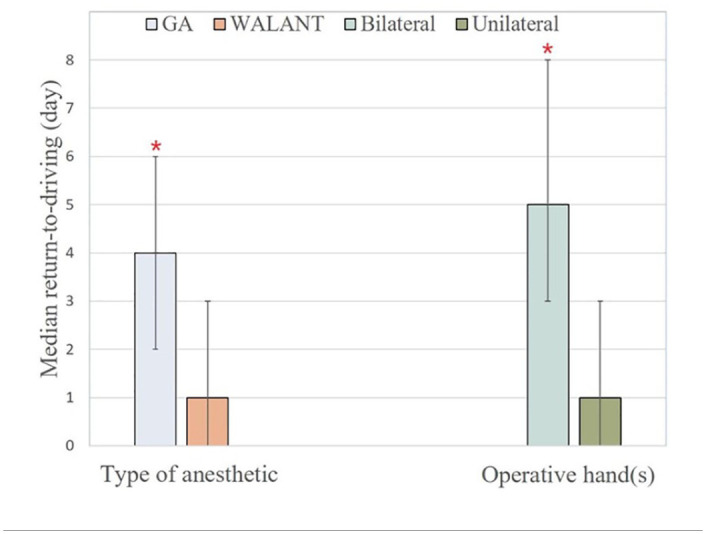

Subjects who underwent GA returned to driving significantly later than subjects who underwent WALANT (4 ± 4 days vs 1 ± 3 days, P = 0.020, Figure 3). Subjects who had bilateral procedures returned to driving significantly later than subjects who had unilateral procedures (5 ± 5 days vs 1 ± 3 days, P = 0.046, Figure 3). There was no statistically significant difference in return-to-driving for left- versus right-sided procedures (1 ± 3 days vs 1 ± 4 days, P = 0.905). Subjects who had access to another driver returned to driving significantly later than subjects who did not have another driver (2 ± 4 days vs 0 ± 0 days, P = 0.040). Subjects who did not drive on the highway returned to driving significantly later than subjects who did drive on the highway (2.5 ± 5.5 days vs 1 ± 3 days, P = 0.005).

Figure 3.

Significant procedure-related factors on return-to-driving after minor hand surgery.

Note. Bar graph demonstrates the median return-to-driving day for type of anesthetic and operative hand(s). Error bars illustrate interquartile range of each variable. *Significant findings of P < 0.05 are demonstrated with a red asterisk between general anesthesia (GA) versus wide awake local anesthetic no tourniquet (WALANT) and bilateral versus unilateral procedures.

Discussion

This return-to-driving study is novel as it is the first prospective study to monitor patients following any type of surgery on a day-to-day basis through text message surveys. Compiling data from a text message-based survey not only eliminates recall bias but also decreases the inconvenience associated with time-consuming research encounters. In this study, we used a prospective text message survey to determine postoperative return-to-driving following minor hand surgery. We demonstrated that about half of patients returned to driving by postoperative day #1. Factors significantly affecting return-to-driving included specific procedure- and driving-related factors, while patient-related factors including socioeconomic and health-related variables had no significant effect.

Hammert et al conducted a retrospective study using telephone interviews, demonstrating patients who underwent minor hand surgery under local anesthesia were less impacted by driving restrictions compared to patients who underwent upper extremity surgery on the forearm, upper arm, or shoulder. 1 They found that 69 out of 139 (49.6%) subjects who underwent minimally invasive procedures returned to driving immediately after surgery and reported the perception of safely doing so. 1 Fifty percent of the subjects who did not return to driving immediately noted the perception that they would have been safe to drive. 1 Although approximately 50% of their subjects returned to driving immediately, Hammert et al highlights recall bias as a limitation that can be mitigated with a prospective study design where data is collected in real time. 1

Our study demonstrates subjects returned to driving significantly later if they underwent GA procedures compared to WALANT procedures. This was an expected result as WALANT procedures do not have the same postoperative recovery associated with GA, and it has been previously demonstrated that patient-driving-ability is not impaired after modeled WALANT procedures. 9 Subjects also returned to driving later if they underwent bilateral procedures versus unilateral procedures. There was no significant difference between left- and right-sided procedures. This delay in return-to-driving for bilateral procedures was expected because of patient-perceived physical ability and specific driving maneuvers that require the use of both hands.

Not unexpectedly, subjects returned to driving later if they had another driver who could provide transportation. The reason for this delay in return-to-driving is unknown, but may be because the pressure and motivation to return to driving was lower if the subject had access to another driver. 3 Interestingly, subjects who did not drive on the highway returned to driving significantly later than subjects who did drive on the highway. The reason for this early return-to-driving goes beyond the scope of this study. However, one possible explanation is that early return-to-driving for subjects who drove on the highway could be due to necessity. 10 Some subjects in this study live in areas where it is required to drive on highways to access grocery stores, medical care, and work, and inability to drive and utilize highways could be economically and socially burdensome. Another possible explanation is that this finding could demonstrate higher risk-taking propensity in subjects who would be more likely to both return to driving sooner and utilize highways compared to subjects who avoid risk-taking by opting to return to driving later and avoid highways. 10 To our knowledge, there are no other studies that explicitly focus on the reasoning behind return-to-driving, and future studies could investigate these factors more in depth.

This study has several limitations. First, this study was underpowered and limited by unexpected attrition. However, we ceased enrollment after interim data analysis between WALANT and GA demonstrated significant findings on return-to-driving. Second, the group investigated was heterogenous with a mixture of different procedure types and patient demographics, and therefore subtle differences by group were not detected. Nonetheless, we did detect major clinically significant differences between groups. Third, the text-message surveys were limited to yes or no responses, limiting a more detailed interpretation of the answers given by participants. Furthermore, our text-message survey did not investigate for patient’s perception of safety in their return to driving. Also, this study excluded non-English speakers, which may have introduced selection bias, hindering the generalization of this study’s outcomes. Lastly, this study was limited to patients who had reliable internet access, were able and willing to text, and wanted to participate in this study. This screening criteria creates a self-selected group, distinct from the general group of all hand surgery patients.

Conclusions

In this study, based on data collection through surveys, we found that most patients return to driving soon after minor hand surgery. In surgical decision-making, WALANT should be considered over GA if patients indicate that a longer return-to-driving date would be burdensome. When scheduling surgeries, patients should be advised that bilateral procedures will prolong postoperative return-to-driving in contrast to unilateral procedures. Patient access should be evaluated and delegated as needed to another driver for transportation if GA or bilateral procedures are elected. Future studies should analyze quality and safety of postop return-to-driving with objective metrics such as postoperative driving tests. In conclusion, we were able to demonstrate that the use of text messages is a valuable instrument for prospective data collection, and we believe the reliability of our results support their future use.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-han-10.1177_15589447221077363 for On the Road Again: Return to Driving Following Minor Hand Surgery by Mary C. Frazier, Darren T. Hackley, Tonja M. Locklear, Ariel E. Badger and Peter J. Apel in HAND

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-han-10.1177_15589447221077363 for On the Road Again: Return to Driving Following Minor Hand Surgery by Mary C. Frazier, Darren T. Hackley, Tonja M. Locklear, Ariel E. Badger and Peter J. Apel in HAND

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-han-10.1177_15589447221077363 for On the Road Again: Return to Driving Following Minor Hand Surgery by Mary C. Frazier, Darren T. Hackley, Tonja M. Locklear, Ariel E. Badger and Peter J. Apel in HAND

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-han-10.1177_15589447221077363 for On the Road Again: Return to Driving Following Minor Hand Surgery by Mary C. Frazier, Darren T. Hackley, Tonja M. Locklear, Ariel E. Badger and Peter J. Apel in HAND

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Cesar J. Bravo, MD; Anthony E. Capito, MD; Horatiu C. Dancea, MD; Hugh J. Hagan, MD; Cassandra R. Mierisch, MD; and Cay M. Mierisch, MD for their support in patient enrollment. The authors are also thankful to Linsen T. Samuel, MD MBA, Christopher R. Deneault, PA-C, and Jadon H. Beck, BA for review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available in the online version of the article.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Musculoskeletal Education and Research Center within the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at Carilion Clinic Institute for Orthopaedics and Neurosciences.

ORCID iDs: Mary C. Frazier  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8004-768X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8004-768X

Darren T. Hackley  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7598-0766

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7598-0766

Peter J. Apel  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5428-2125

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5428-2125

References

- 1. Hammert WC, Gonzalez R, Elfar JC. Evaluation of patients’ perception of safety to drive after outpatient, minimally invasive procedures of the hand. Hand (N Y). 2012;7(4):447-449. doi: 10.1007/s11552-012-9445-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goodwin D, Baecher N, Pitta M, et al. Driving after orthopedic surgery. Orthopedics. 2013;36(6):469-474. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20130523-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen V, Chacko AT, Costello FV, et al. Driving after musculoskeletal injury: addressing patient and surgeon concerns in an urban orthopaedic practice. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(12):2791-2797. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mackenzie JS, Bitzer AM, Familiari F, et al. Driving after upper or lower extremity orthopaedic surgery. Joints. 2018;6(4):232-240. doi: 10.1055/S-0039-1678562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kalamaras MA, Rando A, Pitchford DGK. Driving plastered: who does it, is it safe and what to tell patients. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76(6):439-441. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fnais N, Gomes T, Mahoney J, et al. Temporal trend of carpal tunnel release surgery: a population-based time series analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rees JL, Sharp RJ. Safety to drive after common limb fractures. Injury. 2002;33(1):51-54. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(00)00153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Edwards MR, Oliver MC, Hatrick NC. Driving with a forearm plaster cast: patients’ perspective. Emerg Med J. 2009;26:405-406. doi: 10.1136/emj.2008.062943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thompson Orfield NJ, Badger AE, Tegge AN, et al. Modeled wide-awake, local-anesthetic, no-tourniquet surgical procedures do not impair driving fitness: an experimental on-road noninferiority study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102(18):1616-1622. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.19.01281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jones CM, Ramsey RW, Ilyas A, et al. Safe return to driving after volar plating of distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg Am. 2017;42(9):700-704.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mir HR, Miller AN, Obremskey WT, et al. Confronting the opioid crisis: practical pain management and strategies: AOA 2018 critical issues symposium. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:e126. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.19.00285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moore P. The pain toolkit. Toolkit. 2012;1003:237-240. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kew ST. Text messaging: an innovative method of data collection in medical research. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:342. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Campbell KJ, Louie PK, Bohl DD, et al. A novel, automated text-messaging system is effective in patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101(2):145-151. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.01505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Christie A, Dagfinrud H, Dale Ø, et al. Collection of patient-reported outcomes; —text messages on mobile phones provide valid scores and high response rates. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith A. About this report; 2014. Accessed June 16, 2021. www.pewresearch.org/global/2014/02/13/emerging-nations-embrace-internet-mobile-technology/. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pew Research Center. Demographics of mobile device ownership and adoption in the United States; 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/.

- 18. Na A, Richburg K, Gugala Z. Clinical considerations for return to driving a car following a total knee or hip arthroplasty: a systematic review. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:8921892. doi: 10.1155/2020/8921892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Snook ML, Henry LC, Sanfilippo JS, et al. Text messaging yields high research response rate to track menstrual cycles and patient-reported outcomes. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(2):e38. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.12.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Whitford HM, Donnan PT, Symon AG, et al. Evaluating the reliability, validity, acceptability, and practicality of SMS text messaging as a tool to collect research data: results from the Feeding Your Baby project. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(5):744-749. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Rural-urban continuum codes. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/. Published 2013.

- 22. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/J.JBI.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/J.JBI.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-han-10.1177_15589447221077363 for On the Road Again: Return to Driving Following Minor Hand Surgery by Mary C. Frazier, Darren T. Hackley, Tonja M. Locklear, Ariel E. Badger and Peter J. Apel in HAND

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-han-10.1177_15589447221077363 for On the Road Again: Return to Driving Following Minor Hand Surgery by Mary C. Frazier, Darren T. Hackley, Tonja M. Locklear, Ariel E. Badger and Peter J. Apel in HAND

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-han-10.1177_15589447221077363 for On the Road Again: Return to Driving Following Minor Hand Surgery by Mary C. Frazier, Darren T. Hackley, Tonja M. Locklear, Ariel E. Badger and Peter J. Apel in HAND

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-han-10.1177_15589447221077363 for On the Road Again: Return to Driving Following Minor Hand Surgery by Mary C. Frazier, Darren T. Hackley, Tonja M. Locklear, Ariel E. Badger and Peter J. Apel in HAND