Abstract

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) is an emerging infectious disease caused by SFTS virus (SFTSV). SFTS patients were prone to invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA), which was directly related to increased mortality. Here, we present a critical case of SFTS complicated by IPA in a previously healthy 58-year-old woman. On day 1, SFTSV and three different Aspergillus species were both detected in the patient's bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and blood through metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS). After 17 days of treatment, the patient was still in poor condition and A. fumigatus was once again detected in her blood through mNGS. Then her family decided to give up treatment because of financial problems and grave prognosis. She was discharged home and died the next day. Medical personnel should be alter to the possibility of IPA in SFTS patients due to its high mortality. mNGS may be used as an auxiliary diagnostic tool and efficacy-monitoring method for suspected SFTS complicated by IPA.

Keywords: Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, Metagenomic next-generation sequencing

Introduction

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) is an emerging infectious disease characterized by high fever, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia [1]. SFTS is caused by a novel bunyavirus (SFTS virus, SFTSV) with a high mortality [2]. This disease is transmitted to humans mostly through tick bites, and primarily found in agricultural and mountainous regions of China, Japan, and South Korea [3].

Multiple systemic complications can occur in SFTS patients, among which invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) is one of the most serious. Previous studies had found that SFTS patients were prone to IPA, which was directly related to increased mortality [4], [5]. Thus, timely identification of SFTS and secondary IPA is very important.

As an unbiased and culture-independent method, metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) can identify pathogens rapidly, sensitively and accurately, and is increasingly being applied in clinical practice [6]. Herein, we report a critical case of SFTS complicated by IPA, which was diagnosed by mNGS. After 17 days of treatment, we performed mNGS again to help assess the treatment effect.

Case presentation

On June 11, 2023, a previously healthy 58-year-old woman was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) of our hospital, complaining of a 10-day history of fever, fatigue and generalized body aches, with a temperature up to 38.9 ℃, and a 3-day history of diarrhea, chest tightness and shortness of breath after physical activity. Before admission, she had visited two local hospitals, and was found leukopenic (minimum 1.07 ×109/L) and thrombocytopenic. The patient was given antibiotics (cephalosporin) and antipyretics, but her symptoms did not relieve. As a farmer living in the countryside of Henan Province of China, she was engaged in agriculture before symptoms onset. Although she reported no history of tick bite during the past month, the local residents were often bitten by ticks when working in the fields.

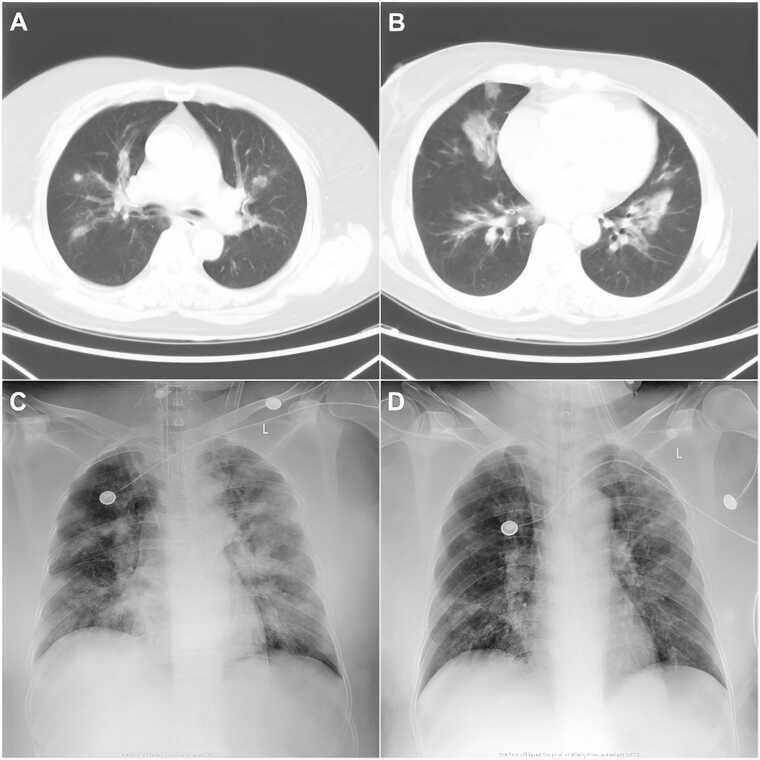

On admission (day 0), physical examination showed temperature of 36.5 ℃, heart rate of 117/min, respiratory rate of 45/min, blood pressure of 170/100 mmHg, conscious state, and crackles in both lungs. Scattered skin petechiae were observed on chest, upper abdomen and both legs. Furthermore, a swollen lymph node was palpable in the right inguinal region. Blood tests revealed leukopenia (white blood cells, 3.1 ×109/L, with 44.2% neutrophil, 27.2% monocytes, and 28.5% lymphocytes), thrombocytopenia (platelets, 24 ×109/L), elevated liver and muscle enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase, 641 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 287 IU/L; creatine kinase, 443 IU/L; lactic dehydrogenase 1721 IU/L), slightly elevated inflammatory indicators (procalcitonin, 0.563 ng/ml; C-reactive protein, 18.03 mg/L), and positive urine occult blood and urine protein. A chest computed tomography (CT) scan showed multiple patchy infiltrations and ground-glass opacities in both lungs (Fig. 1A, B). Bronchoscopy revealed edema of the airway mucosa, and white mold in multiple bronchi, which was partially obstructing the airway. Arterial blood gas analysis showed PH 7.233, PaO2 of 91.8 mmHg, PaCO2 of 55.6 mmHg, and SaO2 of 95.8%. She was preliminary diagnosed as pulmonary infection and sepsis, and empiric antibiotic treatment with intravenous biapenem (0.3 g, q6h) and voriconazole (0.2 g, q12h) was administered. Her blood and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) samples were collected and sent for culture and mNGS.

Fig. 1.

Chest computed tomography (CT) and X-ray images during hospitalization. (A, B) Images of chest CT on the day of admission. (C, D) Images of chest X-ray on day 7 and 13, respectively.

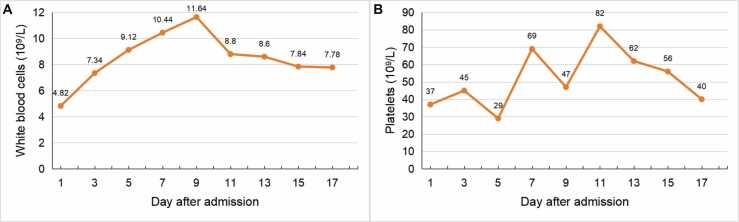

On day 1, the patient experienced mental confusion. Her PaCO2 increased to 79.4 mmHg. She underwent endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. Serological tests for influenza A IgM, influenza B IgM, adenovirus IgM, respiratory syncytial virus IgM, parainfluenza virus IgM, Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgM, and Chlamydia pneumoniae IgM proved negative. Her serum galactomannan (2.80 ng/ml) and 1,3-β-d-glucan (417.79 ng/L) were positive. The mNGS of blood and BALF both reported three different Aspergillus species (A. fumigatus, A. flavus, and A. terreus) and SFTSV (Table 1). SFTS complicated by invasive pulmonary aspergillosis was then confirmed, whereas no pathogens were isolated from the culture of blood and BALF afterwards. Oral ribavirin (1.0 g, q6h) and transfusion of plasma were added to combat the virus. Due to persistent thrombocytopenia (Fig. 2B), transfusion of platelet was performed every two or three days. On day 2, the patient developed acute renal failure and heart failure, and was given continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) and metaraminol therapy, respectively. On day 7, she again developed fever (37.8 ℃). Her white blood cell count (Fig. 2A) and procalcitonin level increased to 10.44 × 109/L and 2.66 ng/ml, respectively. Chest X-ray showed multiple patchy infiltrations (Fig. 1C). Acinetobacter baumannii was isolated from sputum culture and intravenous tigecycline (100 mg, q12h) was given according to the drug susceptibility test results. The patient's pulmonary function improved in the next few days, and radiological findings also improved on day 13 (Fig. 1D).

Table 1.

mNGS results of blood and BALF on day 1.

| Species | Number of sequence reads |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma DNA | Plasma RNA | BALF DNA | BALF RNA | |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 84 | 40 | 858 | 418 |

| Aspergillus flavus | 6 | 2 | 479 | 21 |

| Aspergillus terreus | 64 | 39 | 2203 | 547 |

| SFTSV | ND | 339 | ND | 8 |

| Veillonella parvula | ND | ND | 209 | 19 |

| Olsenella uli | ND | ND | 72 | 9 |

| Eggerthia catenaformi | ND | ND | 46 | 5 |

| Dialister invisus | ND | ND | 21 | 3 |

| Staphylococcus hominis | ND | ND | 7 | ND |

| Staphylococcus capitis | ND | ND | 3 | ND |

| Treponema denticola | ND | ND | 12 | ND |

| Tannerella forsythia | ND | ND | 16 | ND |

Abbreviations: BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; ND, not detected.

Fig. 2.

Dynamics of white blood cell count and platelet count during hospitalization. (A) White blood cell count. (B) Platelet count.

On day 17, the patient was still in poor condition. She suffered from sporadic limb twitching. Blood tests revealed thrombocytopenia (platelets, 40 ×109/L), anemia (red blood cells, 2.41 ×1012/L), elevated creatine kinase (1534 IU/L), and a prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (63.2 s). Bronchoscopy confirmed uncontrolled white mold. On day 18, a repeat mNGS of blood sample reported A. fumigatus with 10 sequence reads from DNA detection, while SFTSV was not detected from RNA detection. Her family decided to give up treatment because of financial problems and grave prognosis. She was discharged home and died the next day.

Discussion

SFTS was first identified in rural areas of China in 2009 and has become a serious threat to global public health, with a high mortality rate and an increasing prevalence [7]. Severe SFTS patients have immune dysfunction including leukopenia and inhibition of innate immunity [2]. IPA is a common type of invasive aspergillosis which usually occurs in immunocompromised patients. Bae et al. reported that among the 36% (16/45) of SFTS patients who were admitted to ICU, 56% developed IPA within a median of 8 days. And mortality was higher in the IPA vs non-IPA patients and in those without vs with anti-fungal treatment [4]. So it is important to early identify SFTS patients with IPA and initiate treatment for patient survival. In the current case, the patient also suffered from A. baumannii infection during hospitalization, with leukocytosis and an elevated procalcitonin level. This suggests that secondary bacterial infection should also be considered in SFTS patients.

It is difficult for clinicians to diagnose SFTS if they don't suspect it. The clinical manifestations of SFTS are nonspecific and similar with multiple infectious diseases, such as anaplasmosis and hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome [8]. Therefore, laboratory confirmation is essential. Specific antibodies to SFTSV can be detected approximately 7 days after symptoms onset, including viral-specific IgM and IgG. But the conduction of serological analysis requires trained personnel and special equipment [9]. In addition, a variety of PCR techniques have been developed to quickly diagnose SFTSV. However, PCR techniques based on the nucleotide sequence of SFTSV strains found in China may be less susceptible to the diagnosis of SFTS lineages found in other countries [10].

mNGS can sequence thousands to billions of DNA fragments and offer information on a broad spectrum of organisms simultaneously. It has a great advantage for the diagnosis of rare or mixed infections, especially in culture-negative specimens [11], [12]. Furthermore, mNGS has been successfully used to help assess treatment efficacy in some clinical cases [13], [14]. However, the relatively high cost of mNGS restricts its wide use in clinics. In this case, mNGS of the patient's blood and BALF both reported three different Aspergillus species and SFTSV on day 1, dramatically avoiding misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis. After 17 days of treatment, the patient was still in poor condition and we repeated mNGS of her blood. A. fumigatus was detected again with a decreased number of sequence reads, suggesting the possibility of persistent IPA.

So far, the best infection control measure for SFTS patients has not been established. Some proposed treatments for SFTS include steroid pulse therapy, plasma exchange, and anti-viral drugs, but their effectiveness remains unclear [15]. So it is imperative for the further study of SFTSV.

Collectively, medical personnel should be alter to the possibility of IPA in SFTS patients due to its high mortality. mNGS may be used as an auxiliary diagnostic tool and efficacy-monitoring method for suspected SFTS complicated by IPA.

Funding

No funding sources to disclose.

Ethical approval

N/A.

Author agreement

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Consent

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient's family for the case details and images to be published. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xing Meng: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Yan Liu: Writing – review & editing. Jun Li: Data curation. Liang Wang: Resources. Ruixue Shi: Visualization. Ying Chen: Investigation. Yun Zhu: Supervision. Shifang Zhuang: Writing – original draft.

Declaration of Competing Interest

No potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Liu S., Chai C., Wang C., Amer S., Lv H., He H., et al. Systematic review of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome: virology, epidemiology, and clinical characteristics. Rev Med Virol. 2014;24(2):90–102. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang T., Xu L., Zhu B., Wang J., Zheng X. Immune escape mechanisms of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.937684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drake M.J., Brennan B., Briley K., Jr, Bart S.M., Sherman E., Szemiel A.M., et al. A role for glycolipid biosynthesis in severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus entry. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bae S., Hwang H.J., Kim M.Y., Kim M.J., Chong Y.P., Lee S.O., et al. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(7):1491–1494. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X., Yu Z., Qian Y., Dong D., Hao Y., Liu N., et al. Clinical features of fatal severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome that is complicated by invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. J Infect Chemother. 2018;24(6):422–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han D., Li R., Tan P., Zhang R., Li J. mNGS in clinical microbiology laboratories: on the road to maturity. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2019;45(5–6):668–685. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2019.1681933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dai Z.N., Peng X.F., Li J.C., Zhao J., Wu Y.X., Yang X., et al. Effect of genomic variations in severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus on the disease lethality. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022;11(1):1672–1682. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2081617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu X.J., Liang M.F., Zhang S.Y., Liu Y., Li J.D., Sun Y.L., et al. Fever with thrombocytopenia associated with a novel bunyavirus in China. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(16):1523–1532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Q., He B., Huang S.Y., Wei F., Zhu X.Q. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, an emerging tick-borne zoonosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(8):763–772. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70718-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seo J.W., Kim D., Yun N., Kim D.M. Clinical update of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Viruses. 2021;13(7):1213. doi: 10.3390/v13071213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng J., Hu H., Kang Y., Chen W., Fang W, Wang K., et al. Identification of pathogens in culture-negative infective endocarditis cases by metagenomic analysis. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2018;17(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s12941-018-0294-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo L.Y., Feng W.Y., Guo X., Liu B., Liu G., Dong J. The advantages of next-generation sequencing technology in the detection of different sources of abscess. J Infect. 2019;78(1):75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang Q., Liang X., Hong D., Fang Y., Tang L., Mu J., et al. Case report: application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in the diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis and its treatment evaluation. Front Med. 2023;9:1044043. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.1044043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin Z.N., Sun Y.C., Wang J.P., Lai Y.L., Sheng L.X. Next-generation sequencing technology for diagnosis and efficacy evaluation of a patient with visceral leishmaniasis: a case report. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9(32):9903–9910. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i32.9903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takayama-Ito M., Saijo M. Antiviral drugs against severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus infection. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:150. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]