Summary

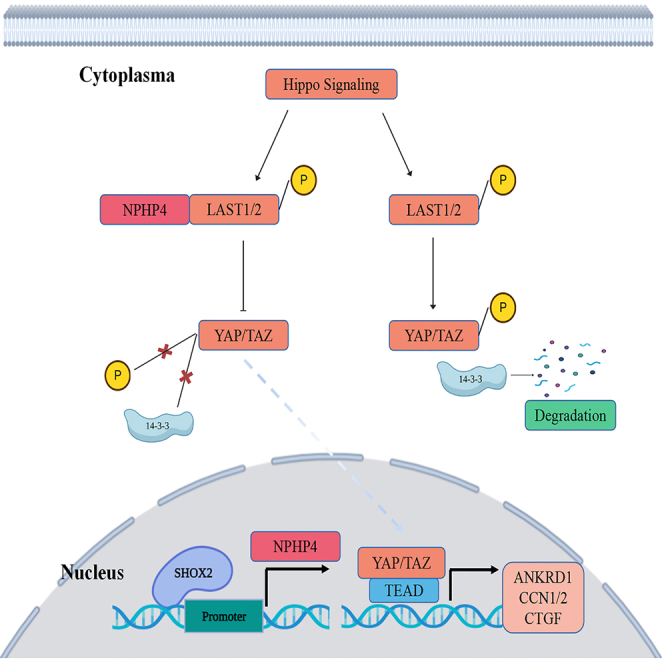

The transcription factor SHOX2 gene is critical in regulating gene expression and the development of tumors, but its biological role in prostate cancer (PCa) remains unclear. In this study, we found that SHOX2 expression was significantly raised in PCa tissues and was associated with clinicopathological features as well as disease-free survival (DFS) of PCa patients. Phenotypic tests showed that the absence of SHOX2 inhibited PCa growth and invasion, while SHOX2 overexpression promoted these effects. Mechanistically, SHOX2 was found to activate the transcription of nephronophthisis type 4 (NPHP4), a gene located downstream of SHOX2. Further analysis revealed that SHOX2 could potentially interfere with the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway through NPHP4 activation, facilitating the oncogenic behavior of PCa cells. These findings highlight SHOX2 as an oncogene in PCa and provide a basis for developing potential therapeutic approaches against this disease.

Subject areas: Biological sciences, Molecular biology, Cancer

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Enhanced SHOX2 levels are linked to advanced progression in PCa patients

-

•

SHOX2 accelerates the proliferation and migration of PCa cells

-

•

SHOX2 regulated the Hippo/YAP signaling pathway

-

•

NPHP4 can partially restore the malignancy traits of SHOX2-inhibited cells

Biological sciences; Molecular biology; Cancer

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most commonly occurring cancer in men worldwide, ranking as the fifth highest cause of cancer-related deaths.1,2,3 The treatment options for advanced stages of the disease include androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT), chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and radiation therapy,4,5 with poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors and prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-targeted therapy showing promising results in clinical trials.6,7 While most patients respond positively to ADT initially, most cases eventually relapse, leading to castration-resistant PCa. Therefore, understanding the key factors involved in each stage is critical to improving the current diagnosis and treatment of PCa.

Short stature homeobox 2 (SHOX2) is a gene that displays homology with the short stature homeobox gene, SHOX, found in humans. The orthologous gene in mice shows a 99% sequence identity at the amino acid level and exhibits analogous expression patterns during embryonic development. Studies on SHOX2 conditional knockout mice have demonstrated that SHOX2 is crucial for the development of the proximal section of the limb skeleton and synovial joints and is indispensable for this process.8,9 The analysis of SHOX2 methylation in plasma DNA enabled the identification of lung cancer and differentiation from non-cancerous diseases. The methylated site is concentrated in the promoter region.10,11 Recent studies also found that the activation of STAT3 led to significant upregulation of SHOX2 in patients with gastric cancer, making it among the top-most expressed genes in this context.12 These findings highlight SHOX2’s importance in tumorigenesis and progression. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that the methylation level of SHOX2 enables differentiation between localized and metastatic disease in PCa patients, with a rise in levels shortly after biopsy.13 However, despite these advances, the precise role played by SHOX2 in PCa biological processes is yet to be comprehensively understood.

Initially recognized as a universally conserved controller of tissue growth, the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway has been demonstrated to govern tumorigenesis, metastasis, and resistance to chemotherapy in diverse types of human cancers.14,15,16 The Hippo pathway comprises a series of kinase enzymes that, in response to diverse stimuli such as cell-to-cell interaction, nutrients, and the microenvironment, obstruct downstream effector proteins (YAP/TAZ) to suppress transcriptional programs that foster cell growth.17,18 The functions of individual constituents of the Hippo signaling pathway in the development and advancement of PC are being unveiled. Previous studies have indicated the crucial involvement of the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway in the development of PCa.19,20,21 In primary tumors, a significant association has been found between the recurrence of tumors following primary treatment and nuclear expression of YAP. Moreover, in castration-resistant prostate patients, YAP has been demonstrated to be upregulated and significantly hyperactivated. However, whether SHOX2 can impact the activation of Hippo pathway signals remains elusive.

The current study involved a systematic exploration of SHOX2 role in PCa and discovered its transcriptional regulatory relationship with NHPH4. Acting upstream of NHPH4, SHOX2 plays a crucial role in driving PCa progression while also revealing a potential mechanism for persistent YAP activation. The study’s investigations further uncovered the mechanisms modulated by SHOX2 to regulate the malignant phenotype of PCa cells.

Results

SHOX2 showed upregulated expression in PCa tissues and cell lines

To investigate the involvement of SHOX2 in the progression of PCa, we examined the expression pattern of SHOX2 in clinical prostatic tumors by utilizing publicly accessible data from our center, TCGA, and GEO datasets. Notably, the expression of SHOX2 was found to be elevated in PCa tissues compared to benign tissues (Figures 1A and S1). Furthermore, the expression of SHOX2 was significantly higher in tumors obtained from patients with Gleason scores 7, 8, 9–10 as compared to tumors with a Gleason score of 6 (Figure 1B). Metastatic PCa tissues showed a similar rise in SHOX2 expression compared to non-metastatic PCa or benign tissues (Figure 1C). Consistently, WB and IHC staining verified that SHOX2 was significantly upregulated in PCa patients (Figures 1D and 1E). In addition, as shown in Figures 1F and 1G, there was a significant increase in both mRNA and protein levels of SHOX2 in PCa cell lines (LNCaP, MDA PCa 2b, C4-2B, PC-3, and VCaP) compared to non-neoplastic prostate epithelial cells (RWPE-1). The expression of SHOX2 was relatively high in the PCa cell lines C4-2B and PC-3, while LNCaP and MDA PCa 2b cells exhibited low SHOX2 expression.

Figure 1.

SHOX2 showed upregulated expression in PCa tissues and cell lines

(A) The TCGA database was utilized to produce graphs that depict the expression of SHOX2 in normal and prostate cancer tissues.

(B) The TCGA database was utilized to produce graphs that depict the correlation between SHOX2 and prostate cancer Gleason grade.

(C) The GEO database GSE35988 was utilized to produce graphs that depict the correlation between SHOX2 expression and prostate cancer metastasis.

(D) SHOX2 protein levels in PCa tumor tissues and corresponding adjacent nontumor tissues.

(E) Representative IHC staining of SHOX2 in PCa tumor tissues as compared with peritumor tissues. Scale bar = 50 μm.

(F and G) SHOX2 mRNA and protein expression levels in PCa cell lines and normal RWPE-1 cells by qRT-PCR and WB analyses. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of experiments performed in triplicate. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

SHOX2 expression was correlated with advanced progression and poor prognosis

Next, we explored whether there was a correlation between SHOX2 expression and the clinicopathological features of PCa patients. A significant correlation between high levels of SHOX2 expression and various clinicopathological characteristics was observed in PCa patients, as indicated in Table S1. These characteristics include T stage (p < 0.001), lymph node metastasis (p = 0.029), high levels of total PSA (p = 0.008), Gleason score (p = 0.015), and the presence of relapse or metastasis (p < 0.002). Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log rank tests showed that patients with elevated expression of SHOX2 had a noticeably lower disease-free survival (DFS) rate compared to those with low SHOX2 expression, as seen in Figure 2A. Furthermore, the results of the multivariate analyses indicated that high expression levels of SHOX2 and N stage were independent prognostic factors associated with DFS, as seen in Figure 2B and Table S2. These results indicate that SHOX2 plays a crucial role in the progression of PCa and suggest that it could serve as a potential marker for predicting a poor prognosis.

Figure 2.

SHOX2 expression was correlated with advanced progression and poor prognosis

(A) Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to compare disease-free survival (DFS) curves between PCa patients with low SHOX2 expression and high SHOX2 expression (n = 106) through a log rank test.

(B) Cox-regression analysis was utilized for multivariate analysis of DFS in a group of 106 PCa patients.

Knockdown of SHOX2 suppressed the proliferation of PCa cells

In order to identify the role of SHOX2, the study utilized lentivirus to suppress and enhance the expression of SHOX2 in PCa cells, respectively. The transfection efficiency was evaluated by qRT-PCR and WB assays, as shown in Figures 3A and 3B. The results of CCK-8 and colony formation assays showed that the overexpression of SHOX2 considerably promoted the proliferation of LNCaP and MDA PCa 2b cells, whereas the knockdown of SHOX2 markedly hindered the growth rate of C4-2B and PC-3 cells, as demonstrated in Figures 3C and 3D. Additionally, the inhibiting of SHOX2 expression substantially increased the proportion of apoptosis in C4-2B and PC-3 cells, as illustrated in Figure 3E. These results suggest that SHOX2 enhances cell growth of PCa cells and inhibits apoptosis.

Figure 3.

Knockdown of SHOX2 suppressed the proliferation of PCa cells

(A and B) QRT-PCR and WB analysis of SHOX2 expression in the indicated cell lines. β-actin was used as a loading control.

(C) The CCK-8 assay results of LNCaP, MDA PCa 2b, C4-2B and PC-3 cells following silencing or overexpression of SHOX2.

(D) Colony formation assay results of LNCaP, MDA PCa 2b, C4-2B and PC-3 cells after knockdown or overexpression of SHOX2.

(E) Flow cytometry was performed to assess the apoptosis rate of C4-2B and PC-3 cells following SHOX2 knockdown. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of experiments performed in triplicate. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

To investigate the impact of SHOX2 deficiency in vivo, stable PC-3 cells with knocked-down SHOX2 expression were established using a lentiviral transfection method. Afterward, these stable PC-3 cell lines were subcutaneously implanted in nude mice to produce xenografts. Consequently, the shSHOX2 group demonstrated a significant decrease in tumor volume and weight compared to the shNC group. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of the SHOX2-deficient tumor tissues showed a reduction in the expression of Ki-67, as depicted in Figures S2A–S2D.

SHOX2 promotes the migration and invasion of PCa cells

Next, we aimed to investigate the function of SHOX2 in tumor metastasis and invasion. The results demonstrated that the migration and invasion ability of LNCaP and MDA PCa 2b cells were significantly enhanced by SHOX2, as shown in Figures 4A and 4C, whereas the knockdown of SHOX2 suppressed their migration and invasion ability, as shown in Figures 4B and 4C. The similar results were verified by conducting wound healing assays, as depicted in Figures 4D–4F.

Figure 4.

SHOX2 promotes the migration and invasion of PCa cells

(A–C) The impact of SHOX2 knockdown and overexpression on the migration of PCa cells was respectively shown using Transwell migration assays, with a scale bar of 200 μm.

(D–F) The effects of SHOX2 knockdown and overexpression on PCa cell migration were evaluated using wound healing assays, with a scale bar of 200 μm. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of experiments performed in triplicate. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Tumor metastasis relies heavily on the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) pathway. Therefore, we conducted WB assays to investigate whether SHOX2 could influence the metastasis of PCa cells via the EMT pathway. The results revealed that SHOX2-knockdown increased the expression of E-cadherin while decreasing the expressions of Vimentin, Slug, and N-cadherin. Conversely, the overexpression of SHOX2 resulted in the opposite patterns, as displayed in Figure 4G.

To determine the impact of SHOX2 on cell metastasis in vivo, an assessment was conducted. Pulmonary metastatic models were created by injecting shSHOX2 and shNC stable PC-3 cells into the tail vein of nude mice. The outcomes revealed that the inhibition of SHOX2 expression stifled lung metastasis in vivo, as demonstrated in Figures S2E and S2F. These findings substantiate the critical role of SHOX2 in the metastasis of PCa cells.

SHOX2 inhibits hippo signaling leading to YAP activation

The suppression of Hippo signaling is a significant factor in contributing to the aggressiveness of PCa.22 To investigate the mechanism underlying the regulation of growth and metastasis of PCa cells by SHOX2, we initially examined alterations in the protein expression profiles of the Hippo signaling pathway in TCGA datasets. We observed a significant decrease in the levels of p-YAP-S127 (which is the phosphorylated form of YAP upon Hippo activation and secluded in the cytoplasm by binding to 14–3–3 protein), in PCa tissues exhibiting increased expression of SHOX2 as opposed to those with low levels of SHOX2 (Figure 5A). Validation through WB assays revealed that overexpression of SHOX2 led to a decrease in phosphorylated YAP levels, while increasing the levels of nuclear localization Yap. Conversely, silencing of SHOX2 had the opposite effect (Figure 5B). However, there is no significant difference in the total protein levels of Yap at different SHOX2 expression levels. QRT-PCR analyses further demonstrated that SHOX2 had no impacts on mRNA levels of Yap (Figure S3A). Moreover, Fluorescence immunostaining results demonstrated that SHOX2 upregulation triggered the translocation of YAP into the nucleus of PCa cells (Figure 5C). Subsequently, we utilized HOP/HIP flash luciferase assays to examine the impact of SHOX2 on the transcriptional activity of YAP. There was a marked increase in the activity ratio of HOP/HIP in PCa cells overexpressing SHOX2, whereas in cells with SHOX2-knockdown, the activity ratio was decreased (Figure 5D). In addition, expression of downstream target genes of YAP, including CCN1, HOXA1, and AMOTL2, was notably increased upon the introduction of SHOX2, whereas it was reduced in cells with SHOX2 knockdown cells (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

SHOX2 inhibits Hippo signaling leading to YAP activation

(A) Through analysis of the TCGA PCa protein dataset, it was observed that p-YAP-S127 expression was considerably reduced in PCa samples belonging to the highest quartiles of SHOX2 in comparison to those in the lowest quartiles, as determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test.

(B) The expression of the specified proteins was assessed via WB assay in the mentioned cells, with β-actin utilized as a loading control for total extracts and P84 used as a loading control for nuclear extracts.

(C) The expression and subcellular localization of YAP were examined in the mentioned cells with modified SHOX2 expression and visualized through fluorescence and laser confocal microscopy. The scale bars of 20 μm were used. (Left panel); The proportion of YAP subcellular localization was determined as a percentage and categorized as either nucleus (N) or cytoplasm (C). (Right panel).

(D) The activity of HOP/HIP luciferase was examined in the specified cells. HOP-Flash luciferase assay was employed to determine the transcriptional activity of YAP/TAZ-TEAD.

(E) The qRT-PCR analysis was performed to compare the mRNA expression fold change of the specified genes between cells overexpressing SHOX2 and those with vector, as well as shSHOX2 versus shNC. The fold change values were generated by log2 transformation. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of experiments performed in triplicate. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

NPHP4, an essential suppressor of Hippo signaling, is upregulated transcriptionally by SHOX2

In the Hippo signaling cascade, MST1/2 activates LATS1/2 by phosphorylation, which in turn phosphorylates YAP at Ser127. This leads to YAP being held in the cytoplasm and degraded.17 The downstream target genes that are controlled by SHOX2 as a transcription factor in PCa have yet to be explored.

To investigate how SHOX2 suppresses the Hippo-YAP pathway, we analyzed whether SHOX2 influences the transcription of inhibitors of Hippo signaling, including NPHP4, TP53BP2, CIT, and RACGAP1.23,24,25 By analyzing the TCGA PRAD cohort, we noticed a remarkable association between SHOX2 mRNA levels and the expression of NPHP4, exhibiting a robust positive correlation, as illustrated in Figure S4A. QRT-PCR and WB analyses further confirmed that NPHP4 expression was increased in PCa cells overexpressing SHOX2, while it was significantly reduced in cells where SHOX2 was silenced, as shown in Figures 6A and 6B and Figure S4B. These findings indicate that SHOX2 might regulate the activity of YAP by stimulating the expression of NPHP4. The possible transcriptional binding site for SHOX2 in the NPHP4 promoter region was identified based on its ability to selectively bind to the ATTA(N)nTAAT consensus sequences.26 To investigate the transcriptional regulation of NPHP4 by SHOX2, we generated promoter-reporter plasmids containing both wild-type and mutated versions of the SHOX2 binding site, as shown in Figure 6C. The results showed that SHOX2 substantially enhanced the activity of the wild-type promoter, while it had no impact on the activity of the mutant promoters, as shown in Figure 6D. The ChIP assay provided further confirmation that SHOX2 was present in the promoter region of NPHP4, as depicted in Figure 6E. In addition, overexpression of SHOX2 led to an increase in the levels of p300, RNA polymerase II, and the gene-activating marks H3K4me3 on the NPHP4 promoter, while the silencing of endogenous SHOX2 resulted in a reduction in their enrichment, as shown in Figure 6F.

Figure 6.

NPHP4, an essential suppressor of Hippo signaling, is upregulated transcriptionally by SHOX2

(A and B) QRT-PCR and WB analysis NPHP4 expression in SHOX2 silenced-, SHOX2 overexpressing-, and control cells.

(C) A schematic diagram of the NPHP4 promoter was presented, including the sequences of the wild-type and mutant SHOX2 binding sites. (Left panel); The luciferase activity of the SHOX2 promoter reporter was quantified in the mentioned cells. (Right panel).

(D) The enrichment of SHOX2 on the NPHP4 gene promoter was evaluated through ChIP analysis. A negative control was established using IgG.

(E) The mentioned cells were subjected to ChIP assays using anti-p300 acetyltransferase, anti-RNA POL II (RNAP II), and anti-H3K4me3 antibodies. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of experiments performed in triplicate. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

SHOX2 promotes PCa proliferation and metastasis by transactivating NPHP4

Previous studies reported NPHP4 did not affect the autophosphorylation of Lats1 but interfered the physical interaction of phosphorylated Lats1 with Yap.23 Validation through WB assays revealed that overexpression of NPHP4 led to an increase in phosphorylated YAP, while did not affect the level of Yap, Lats1 and p-Lats1 (Figure S4C). Subsequently, we evaluated how the viability, migration, and invasion of PCa cells were affected by SHOX2-mediated NPHP4. The results of CCK-8 and colony formation assays showed that NPHP4 overexpression could rescue the cell viability inhibited by SHOX2 knockdown cells, as displayed in Figures 7A and 7B. Transwell and wound healing assays further showed that the migration and invasion of LNCaP and MDA PCa 2b cells were enhanced by overexpression of NPHP4 in SHOX2 knockdown cells, as shown in Figures 7C and 7D. Taken together, these findings indicate that SHOX2 promotes the proliferation and aggressiveness of PCa cells by inducing the expression of NPHP4.

Figure 7.

SHOX2 promotes PCa proliferation and metastasis by transactivating NPHP4

(A) Rescuing CCK-8 assays in C4-2B and PC-3 cells.

(B) Rescuing colony-forming assays in C4-2B and PC-3 cells.

(C) Rescuing wound healing assay in C4-2B and PC-3 cells.

(D) Rescuing Transwell migration assays in C4-2B and PC-3 cells. The scale bar for migration images is 200 μm. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of experiments performed in triplicate. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Clinical relevance of the SHOX2/NPHP4/YAP axis in human PCa

Ultimately, we evaluated the clinical relevance of the SHOX2 and YAP signaling pathways in PCa patients. Immunohistochemical staining revealed a noteworthy and affirmative correlation (p < 0.001) between SHOX2 expression and both NPHP4 expression and YAP expression, as displayed in Figures 8A and 8B. Survival analysis demonstrated that in all patients with PCa, those who exhibited high expression of both SHOX2 and NPHP4, or high expression of SHOX2 and YAP, had a poorer DFS compared to other groups, as shown in Figure 8C. This suggests that the overexpression of SHOX2, in conjunction with NPHP4 or YAP, is a significant prognostic indicator for PCa patients.

Figure 8.

Clinical relevance of the SHOX2 /NPHP4/ YAP axis in human PCa

(A) The IHC staining of SHOX2, NPHP4, YAP, and p-YAP was performed in 106 prostate cancer patient specimens, and representative images were presented. The scale bars in the images were 50 μm.

(B) Proportion of PCa samples displaying SHOX2 expression in relation to the levels of NPHP4 and YAP.

(C) Survival analysis of patients with PCa (n = 106) using Kaplan-Meier method. The p-values obtained from log rank test are presented.

Discussion

Despite reports of SHOX2 having oncogenic roles in multiple malignancies,27,28,29 its function in PCa remains poorly understood. According to Teng et al.,26 SHOX2 expression levels are strongly correlated with poor distant metastasis-free survival in breast cancer patients. Additionally, SHOX2 inactivation can suppress breast tumor growth and metastasis by directly suppressing the metastasis-promoting gene Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein family member 3 (WASF3). Expression of SHOX2 also seems to serve as a functional prognostic marker and has been utilized as an independent criterion for grade II and III diffuse gliomas.30 Furthermore, inhibiting the expression of SHOX2 could significantly reduce the proliferation and metastasis of oral squamous cell carcinoma.31 In PCa, early changes in methylated SEPT9 and SHOX2 in circulating cell-free plasma DNA can differentiate between patients with and without PCa and serve as a promising marker for tumor monitoring during systemic therapy to determine tumor burden in the metastatic stage.13 However, the mechanism by which SHOX2 regulates PCa progression remains unknown. In the present study, we found that SHOX2 levels were markedly elevated in PCa tissues compared to normal tissues. Subsequent analysis showed that increased SHOX2 expression correlated with TNM stage, total PSA levels, and Gleason score, and was indicative of a higher likelihood of metastatic relapse in PCa patients. These findings suggest that SHOX2 expression is a potential marker of aggressive PCa.

The development of tumors involves a series of steps in which oncogenes are abnormally expressed or tumor suppressor genes are deactivated.32 Lymph node metastasis and bone metastasis represent the most prevalent forms of metastasis in PCa. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a process in which tumor-associated epithelial cells acquire mesenchymal characteristics. This transformation endows these cells with augmented mobility and an increased propensity for invasion.33 The EMT phenomenon has been linked to several signaling pathways - notably the WNT/β-catenin pathway and Hippo-YAP pathway. Recent research indicates that UBE2S enhances the oncogenic effects in PCa bone metastasis by targeting p16 for degradation and stabilizing β-catenin through K11-linked ubiquitination.34 Furthermore, numerous tumor-associated immune cells, predominantly tumor-associated macrophages, are known to play a crucial role in cancer metastasis.35 This study revealed that overexpression of SHOX2 stimulated the proliferation and migration of PCa cells, whereas inhibition of SHOX2 had the opposite effect. Moreover, elevated levels of SHOX2 expression could induce EMT by suppressing E-cadherin and promoting the expression of Vimentin, Slug, and N-cadherin proteins, ultimately promoting PCa cell metastasis.

YAP, as the main mediator of the Hippo signaling pathway, plays a crucial role in regulating organ growth and cell proliferation. Growing evidence suggests that overexpression of YAP and its nuclear localization are associated with a poor prognosis and treatment resistance in PCa patients. Furthermore, YAP may be involved in the development of treatment resistance in PCa.36,37 In this study, we discovered that upregulation of SHOX2 resulted in a reduction of phosphorylated YAP and LATS1 levels, along with an increase in YAP levels and its localization in the nucleus.

NPHP4 is a protein typically associated with cilia and frequently mutated in nephronophthisis, a severe degenerative renal disease.38 Recent studies revealed that NPHP4 acts as a potent inhibitor of mammalian Hippo signaling by directly interacting with Lats1 kinase, which leads to the inhibition of Lats1-mediated phosphorylation of YAP.23 Consequently, proto-oncogenic transcriptional regulators are derepressed. Through bioinformatics analysis, we observed a significant correlation between NPHP4 and SHOX2 expression levels in PCa tissues, which led us to hypothesize that SHOX2 might play a role in the development of the malignant phenotype of PCa cells by facilitating NPHP4 transactivation. To validate this hypothesis, we conducted ChIP-qPCR and dual-luciferase reporter assays in this study, which confirmed that SHOX2 could directly bind to the NPHP4 promoter, enhance transcription, and increase expression. Furthermore, rescue assays demonstrated that overexpression of NPHP4 could restore cell proliferation and migration in the absence of SHOX2. These findings suggest that NPHP4 plays an essential role in the SHOX2-mediated promotion of PCa cell proliferation and migration, potentially offering a potential therapeutic target for PCa treatment.

In conclusion, our study has identified SHOX2 as an oncogene in PCa. Mechanistically, SHOX2 was found to bind to the promoter of NPHP4, resulting in enhanced transcription and inhibition of the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway. This, in turn, promotes the malignant phenotype in PCa cells. These findings suggest that SHOX2 and NPHP4 may serve as potential diagnostic and therapeutic targets for the treatment of aggressive PCa.

Limitations of the study

The evidence obtained in vivo relies on a single experimental model. For instance, the mice bone metastasis missing. Furthermore, it remains to be further elucidated whether there are any co-regulatory transcription factors involved in mediating the regulation of NPHP4 expression by the transcription factor SHOX2.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| SHOX2 | Abcam | ab55740; RRID: AB_945451 |

| NPHP4 | Proteintech | 13812-1-AP; RRID: AB_10640302 |

| Yap | Abcam | ab52771; RRID: AB_2219141 |

| P-Yap (S127) | Abcam | ab283327 |

| Lats1 | Abcam | ab234820 |

| P-Lats1 (T1079) | Abcam | ab305029 |

| P84 | Abcam | ab487; RRID: AB_304696 |

| Mst1/2 | Cell signaling technology Lnc | 14946; RRID: AB_2798654 |

| P-Mst-1 | Cell signaling technology Lnc | 49332; RRID: AB_2799355 |

| E-Cadherin | Cell signaling technology Lnc | 14472; RRID: AB_2728770 |

| N-Cadherin | Cell signaling technology Lnc | 13316 |

| Vimentin | Cell signaling technology Lnc | 46173 |

| Slug | Cell signaling technology Lnc | 9585; RRID: AB_2239535 |

| β-actin | Cell signaling technology Lnc | 4970; RRID: AB_2223172 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| LV-SHOX2 | GeneChem Co., Ltd | N/A |

| LV-shSHOX2 | GeneChem Co., Ltd | N/A |

| LV-NPHP4 | GeneChem Co., Ltd | N/A |

| LV-shNPHP4 | GeneChem Co., Ltd | N/A |

| Biological samples | ||

| Fresh PCa tissues | Peking union medical college hospital | N/A |

| Paraffin tissue section of PCa patients | Peking union medical college hospital | N/A |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| CCK-8 | MedChemExpress | Cat # HY-K0301 |

| TRIzol | Invitrogen | Cat # 15596026 |

| RIPA Lysis Buffer | MedChemExpress | Cat # HY-K1001 |

| Matrigel Matrix | Corning | Cat # 356234 |

| Apoptosis Analysis Kit | MedChemExpress | Cat # HY-K1071 |

| D-Luciferin | MedChemExpress | Cat # HY-12591A |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| PC-3 | ATCC | CRL-1435 |

| LNCaP | ATCC | CRL-3313 |

| C4-2B | ATCC | CRL-3315 |

| VCaP | ATCC | CRL-2876 |

| MDA PCa 2b | ATCC | CRL-2422 |

| RWPE-1 | ATCC | CRL-11609 |

| HEK293T | ATCC | CRL-11268 |

| Experimental models: mouse | ||

| BALB/c-nu mice | Animal Resources Center of Peking Union Medical College | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| SHOX2 forward TTGGACTCGGAAAGCCAGAC | Invitrogen | N/A |

| SHOX2 reverse ATAAGGGGGTGGGAGGAGAC | Invitrogen | N/A |

| CCN1 forward GGTCAAAGTTACCGGGCAGT | Invitrogen | N/A |

| CCN1 reverse GGAGGCATCGAATCCCAGC | Invitrogen | N/A |

| HOXA1 forward TCCTGGAATACCCCATACTTAGC | Invitrogen | N/A |

| HOXA1 reverse GCACGACTGGAAAGTTGTAATCC | Invitrogen | N/A |

| AMOTL2 forward ACCATGCGGAACAAGATGGAC | Invitrogen | N/A |

| AMOTL2 reverse GGCGGCGATTTGCAGATTC | Invitrogen | N/A |

| HOXC13 forward CTCATCCCCGTCGAAGGCTA | Invitrogen | N/A |

| HOXC13 reverse GCTGCACCTTAGTGTAGGGC | Invitrogen | N/A |

| EDN1 forward AGAGTGTGTCTACTTCTGCCA | Invitrogen | N/A |

| EDN1 reverse CTTCCAAGTCCATACGGAACAA | Invitrogen | N/A |

| BIRC2 forward GAATCTGGTTTCAGCTAGTCTGG | Invitrogen | N/A |

| BIRC2 reverse GGTGGGAGATAATGAATGTGCAA | Invitrogen | N/A |

| SOX6 forward TACCTCTACCTCACCACATAAGC | Invitrogen | N/A |

| SOX6 reverse ACATCGGCAAGACTCCCTTTG | Invitrogen | N/A |

| CCN2 forward CAGCATGGACGTTCGTCTG | Invitrogen | N/A |

| CCN2 reverse AACCACGGTTTGGTCCTTGG | Invitrogen | N/A |

| ANKRD1 forward CGTGGAGGAAACCTGGATGTT | Invitrogen | N/A |

| ANKRD1 reverse GTGCTGAGCAACTTATCTCGG | Invitrogen | N/A |

| AREG forward GAGCCGACTATGACTACTCAGA | Invitrogen | N/A |

| AREG reverse TCACTTTCCGTCTTGTTTTGGG | Invitrogen | N/A |

| FGF2 forward AGAAGAGCGACCCTCACATCA | Invitrogen | N/A |

| FGF2 reverse CGGTTAGCACACACTCCTTTG | Invitrogen | N/A |

| BIRC5 forward AGGACCACCGCATCTCTACAT | Invitrogen | N/A |

| BIRC5 reverse AAGTCTGGCTCGTTCTCAGTG | Invitrogen | N/A |

| NPHP4 forward AATGAAGGGGTCATTGATGG | Invitrogen | N/A |

| NPHP4 reverse TCAGGAAGAAGGTGGAACGC | Invitrogen | N/A |

| GAPDH forward AAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTCAA | Invitrogen | N/A |

| GAPDH reverse AATGAAGGGGTCATTGATGG | Invitrogen | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 8.0 software | GraphPad Prism Software Inc. | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Zhigang Ji (jzgjxmc@163.com).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents and all materials in this study are commercially available.

Experimental model and study participant details

Patients and samples

A total of 106 clinical specimens from Peking Union Medical College Hospital between 2012 and 2022 were included in this study. The tissues were obtained during surgery or through needle biopsy. The Research Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (Beijing, China) approved the study protocol, which was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to the use of human tissue samples, informed consent forms were obtained from each patient or their relatives. Clinical data for each patient are presented in Table S1.

Cell culture

Immortalized prostate epithelial cell line RWPE-1, Androgen-sensitive cell lines MDA PCa 2b and LNCaP, Castration-resistant prostate cancer cell lines PC-3, VCaP, and C4-2B and Human Embryonic Kidney Cells ,293T (HEK293T) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). HEK293T and VCaP cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, 01-052-1ACS, Biological Industries, Israel). MDA PCa 2b, PC-3, LNCaP, C4-2B, cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium (01-100-1A, Biological Industries, Israel). 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution were added to all media. RWPE-1 cells were cultured in Keratinocyte Serum Free Medium (K-SFM) kit (17005-042 , Invitrogen, USA).

Animal models

We procured 20 female BALB/C-nu/nu mice (4-6 weeks old) from the Laboratory Animal Resources Center of Peking Union Medical College. In each experimental group, four mice were utilized. The mice were injected with 1 × 106 PC-3-shNC or PC-3-shSHOX2 cells in 100 μL of PBS. Tumor size and body weight were measured every three days. In the metastasis assay, 1.5 × 106 PC-3 cells with sh-NC and sh-SHOX2 were suspended in 150 μL of PBS and administered to mice through tail vein injections. After one month, the mice were sacrificed. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Peking Union Medical College.

Method details

Bioinformatics and data analysis

The levels of SHOX2 mRNA in both normal prostate and PCa tissues were evaluated by analyzing multiple PCa mRNA datasets, including GSE35988 obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), as well as the prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD) dataset obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data portal (https://tcga.data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/tcgaHome2.jsp). Further analysis was performed by dividing the patients into two groups with low and high levels of mRNA expression.

Cell transfection

The PCa cell lines, PC-3 and C4-2B were transfected with lentiviruses for SHOX2 or NPHP4 knockdown, a negative control (shSHOX2/shNC; shNPHP4/shNC). MDA PCa 2b and LNCaP were transfected with lentiviruses for SHOX2 or NPHP4 overexpression or scrambled (SHOX2/Vector; NPHP4/Vector). Then, the cells were incubated in humidified incubators at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 hours. We selected stable transfected cells over 14 days using puromycin at a concentration of 10μg/mL.

Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Trizol reagent was utilized to extract Total RNA, which was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the ReverTraAce qPCR RT kit for RT-PCR. The qRT-PCR analysis was performed using the SYBR Green reagent on a CFX96 Real-Time System C1000 Cycler in accordance with the manufacturer's guidelines. The primer sequences are detailed in key resources table.

Immunoblotting

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously39 with primary antibodies against SHOX2 (ab55740, Abcam), NPHP4 (13812-1-AP, proteintech), YAP (ab52771, Abcam), Lats1 (ab234820, Abcam), p-YAP (S127) (ab283327, Abcam); p-Lats1 (T1079) (ab305029, Abcam); E-Cadherin (14472, Cell Signaling); N-Cadherin (13316, Cell Signaling); Vimentin (46173, Cell Signaling); Slug (9585, Cell Signaling). β-actin (4970, Cell Signaling); P84 (ab487; Abcam).

Flow cytometry analysis

To detect apoptosis, flow cytometry and Annexin V staining (Vazyme) were employed in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. The process involved harvesting 5×105 cells, washing them with PBS, and subsequently staining them with Annexin V and propidium iodide. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the stained cells.

Wound healing assay

To perform a scratch assay, the cells must be seeded into six-well plates and scratched when they reach nearly 100% confluence. Following this, the cells should be washed twice with sterile PBS and then cultured in a serum-free medium. The scratch area must be photographed at 0 h and 24 h to document the progression of the assay. The scratch area was monitored and documented at specified intervals using an inverted microscope.

Transwell assay

To carry out the cell migration assay, a total of 5 × 104 cells in serum-free medium was prepared and used to seed the upper compartment of the insert (8.0μm pore size). Subsequently, 500μL of complete medium was added to the lower chamber. Following a 36-hour incubation period, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained using Giemsa. Using Image J software, five randomly selected visual fields were captured and counted.

Cell proliferation and colony formation assay

To assess cell proliferation, the cell-counting kit 8 (CCK-8) assay kit was utilized, following the manufacturer's protocol. For the colony formation assay, stable transfected PCa cells were seeded at a density of 1000 cells per well in six-well plates. After two weeks, the plates were harvested, and the colonies were treated with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes. Following this, a stain of 0.1% crystal violet was applied for 15 minutes, and the colonies were counted using Image J software.

Luciferase reporter assay

To begin the luciferase activity assay, a total of 5 × 104 cells were plated in triplicate in 48-well plates, as specified. These cells were co-transfected with either the pGL3-SHOX2-luciferase plasmid or the control luciferase plasmid, using the Lipofectamine 3000 reagent from Invitrogen. After 24 hours, the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit from Promega was used to measure the Luciferase and Renilla signals, following the manufacturer's protocol. The measurement of Firefly luciferase activity was then standardized to the Renilla luciferase activity values.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

To conduct the CHIP assay, the Beyotime Chromatin immunoprecipitation kit was utilized, following the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Initially, to crosslink the proteins to DNA, cells that had been transfected with pGL3-SHOX2 were treated with a 1% formaldehyde solution. Crosslinking was terminated using glycine, and the cells were collected and sonicated to fragment the chromatin. Next, the anti-SHOX2 antibody and negative control IgG antibody was incubated overnight at 4°C with the DNA-protein complexes. The immunoprecipitated chromatin was then washed with low- or high-salt buffers, and the crosslinks between DNA and protein were eluted before conducting qRT-PCR. The sequences for SHOX2 promoter were detailed in Table S3.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis

Tissues fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin were sectioned into 4 μm-thick slices, which were then mounted on slides. The sections were treated with 10 mmol/L sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for antigen retrieval, blocked with 5% goat serum for 10 minutes, and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against SHOX2, YAP, p-YAP, or Ki67. The following day, the specimens were incubated with secondary antibodies for 30 minutes at 37°C, treated with 3,3ʹ-diaminobenzidine for 5 minutes, and stained with hematoxylin. The degree of IHC staining was scored based on the percentage of positively stained cells (score 0: 0%–5%; score 1: 6%–35%; score 2: 36%–70%; score 3: 51%–75%; score 4: >75%) and staining intensity (score 0: negatively stained; score 1: weakly stained; score 2: moderately stained; score 3: strongly stained). The final score was calculated by multiplying the positive cells score by the staining intensity score ("0" for a score of 0–1, "1" for a score of 2–3, "2" for a score of 4–6, and "3" for a score of >6). The expression of SHOX2, YAP, p-YAP and Ki67 was evaluated by two independent experienced pathologists.

Immunofluorescence staining

The tumor cells were treated by first fixing them with pre-cooled formaldehyde for 30 minutes, followed by permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-Mel 100 for 15 minutes. The cells were then washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin for 1 hour at room temperature. Primary antibodies against Yap were incubated with the cells overnight at 4°C. On the following day, the cells were incubated with secondary antibodies at 37°C for 30 minutes, restained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), observed under a fluorescence microscope.

Quantification and statistical analysis

The results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the experiments, with each experiment repeated at least three times. Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. The statistical differences between two groups were determined using Student's t-test. The correlation between SHOX2 expression and clinical pathology was evaluated using the chi-squared test. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to calculate the overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) rates of PCa patients, and differences between them were determined using log-rank tests. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank all those who participated in this study. This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (82171588) and National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-B-008).

Author contributions

W.Y., H.C., and L.M.: Acquisition of data. W.Y. performed and monitored the production of the experiments. X.X. and J.D.: Analysis and interpretation of data. M.W. and Z.J.: Conception and design. Y.L.: Data curation. Z.J.: Development of methodology. W.X. and Z.J.: Writing the manuscript and revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: August 11, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.107617.

Contributor Information

Weifeng Xu, Email: weifengxu2008@sina.com.

Zhigang Ji, Email: jzgjxmc@163.com.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

-

•

Data: All the data reported in this study will be shared by the lead contact upon request. This paper analyzes existing, publicly available data. These accession numbers for the datasets are listed in the key resources table.

-

•

Code: This study does not report any original code. Two PCa datasets were downloaded from the TCGA and GEO datasets (GSE35988).

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Wagle N.S., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;1:17–48. doi: 10.3322/caac.21763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seibert T.M., Garraway I.P., Plym A., Mahal B.A., Giri V., Jacobs M.F., Cheng H.H., Loeb S., Helfand B.T., Eeles R.A., Morgan T.M. Genetic Risk Prediction for Prostate Cancer: Implications for Early Detection and Prevention. Eur. Urol. 2023;83:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2022.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ge R., Wang Z., Montironi R., Jiang Z., Cheng M., Santoni M., Huang K., Massari F., Lu X., Cimadamore A., et al. Epigenetic modulations and lineage plasticity in advanced prostate cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2020;31:470–479. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teo M.Y., Rathkopf D.E., Kantoff P. Treatment of Advanced Prostate Cancer. Annu. Rev. Med. 2019;70:479–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-051517-011947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu Y., Song G., Xie S., Jiang W., Chen X., Chu M., Hu X., Wang Z.W. The roles of PD-1/PD-L1 in the prognosis and immunotherapy of prostate cancer. Mol. Ther. 2021;29:1958–1969. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fizazi K., Piulats J.M., Reaume M.N., Ostler P., McDermott R., Gingerich J.R., Pintus E., Sridhar S.S., Bambury R.M., Emmenegger U., et al. Rucaparib or Physician's Choice in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023;388:719–732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2214676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadaghiani M.S., Sheikhbahaei S., Werner R.A., Pienta K.J., Pomper M.G., Solnes L.B., Gorin M.A., Wang N.Y., Rowe S.P.A. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Effectiveness and Toxicities of Lutetium-177-labeled Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen-targeted Radioligand Therapy in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2022;1:82–94. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2021.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider K.U., Sabherwal N., Jantz K., Röth R., Muncke N., Blum W.F., Cutler G.B., Rappold G. Identification of a major recombination hotspot in patients with short stature and SHOX deficiency. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;77:89–96. doi: 10.1086/431655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rappold G.A., Fukami M., Niesler B., Schiller S., Zumkeller W., Bettendorf M., Heinrich U., Vlachopapadoupoulou E., Reinehr T., Onigata K., Ogata T. Deletions of the homeobox gene SHOX (short stature homeobox) are an important cause of growth failure in children with short stature. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002;87:1402–1406. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss G., Schlegel A., Kottwitz D., König T., Tetzner R. Validation of the SHOX2/PTGER4 DNA Methylation Marker Panel for Plasma-Based Discrimination between Patients with Malignant and Nonmalignant Lung Disease. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017;12:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.08.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei B., Wu F., Xing W., Sun H., Yan C., Zhao C., Wang D., Chen X., Chen Y., Li M., Ma J. A panel of DNA methylation biomarkers for detection and improving diagnostic efficiency of lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-96242-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang J., Chen Y.X., Zhang B. IGF2-AS affects the prognosis and metastasis of gastric adenocarcinoma via acting as a ceRNA of miR-503 to regulate SHOX2. Gastric Cancer. 2020;23:23–38. doi: 10.1007/s10120-019-00976-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krausewitz P., Kluemper N., Richter A.P., Büttner T., Kristiansen G., Ritter M., Ellinger J. Early Dynamics of Quantitative SEPT9 and SHOX2 Methylation in Circulating Cell-Free Plasma DNA during Prostate Biopsy for Prostate Cancer Diagnosis. Cancers. 2022;14:4355. doi: 10.3390/cancers14184355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma Y., Yang Y., Wang F., Wei Q., Qin H. Hippo-YAP signaling pathway: A new paradigm for cancer therapy. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;137:2275–2286. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang Y., Fang G., Guo F., Zhang H., Chen X., An L., Chen M., Zhou L., Wang W., Ye T., et al. Selective Inhibition of STRN3-Containing PP2A Phosphatase Restores Hippo Tumor-Suppressor Activity in Gastric Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;38:115–128.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li C., Wang S., Xing Z., Lin A., Liang K., Song J., Hu Q., Yao J., Chen Z., Park P.K., et al. A ROR1-HER3-lncRNA signalling axis modulates the Hippo-YAP pathway to regulate bone metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017;19:106–119. doi: 10.1038/ncb3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moya I.M., Halder G. Hippo-YAP/TAZ signalling in organ regeneration and regenerative medicine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019;20:211–226. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0086-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Q., Wang M., Hu Y., Zhao E., Li J., Ren L., Wang M., Xu Y., Liang Q., Zhang D., et al. MYBL2 disrupts the Hippo-YAP pathway and confers castration resistance and metastatic potential in prostate cancer. Theranostics. 2021;11:5794–5812. doi: 10.7150/thno.56604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu M., Peng R., Liang X., Lan Z., Tang M., Hou P., Song J.H., Mak C.S.L., Park J., Zheng S.E., et al. P4HA2-induced prolyl hydroxylation suppresses YAP1-mediated prostate cancer cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. Oncogene. 2021;40:6049–6056. doi: 10.1038/s41388-021-02000-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee H.C., Ou C.H., Huang Y.C., Hou P.C., Creighton C.J., Lin Y.S., Hu C.Y., Lin S.C. YAP1 overexpression contributes to the development of enzalutamide resistance by induction of cancer stemness and lipid metabolism in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2021;40:2407–2421. doi: 10.1038/s41388-021-01718-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salem O., Hansen C.G. The Hippo Pathway in Prostate Cancer. Cells. 2019;8:370. doi: 10.3390/cells8040370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koinis F., Chantzara E., Samarinas M., Xagara A., Kratiras Z., Leontopoulou V., Kotsakis A. Emerging Role of YAP and the Hippo Pathway in Prostate Cancer. Biomedicines. 2022;10:2834. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10112834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Habbig S., Bartram M.P., Müller R.U., Schwarz R., Andriopoulos N., Chen S., Sägmüller J.G., Hoehne M., Burst V., Liebau M.C., et al. NPHP4, a cilia-associated protein, negatively regulates the Hippo pathway. J. Cell Biol. 2011;193:633–642. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201009069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu X., Zhang X., Yu L., Zhang C., Ye L., Ren D., Li Y., Sun X., Yu L., Ouyang Y., et al. Zinc finger protein 367 promotes metastasis by inhibiting the Hippo pathway in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2020;39:2568–2582. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-1166-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang X.M., Cao X.Y., He P., Li J., Feng M.X., Zhang Y.L., Zhang X.L., Wang Y.H., Yang Q., Zhu L., et al. Overexpression of Rac GTPase Activating Protein 1 Contributes to Proliferation of Cancer Cells by Reducing Hippo Signaling to Promote Cytokinesis. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1233–1249.e22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teng Y., Loveless R., Benson E.M., Sun L., Shull A.Y., Shay C. SHOX2 cooperates with STAT3 to promote breast cancer metastasis through the transcriptional activation of WASF3. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021;40:274. doi: 10.1186/s13046-021-02083-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang T., Zhang H., Cai S.Y., Shen Y.N., Yuan S.X., Yang G.S., Wu M.C., Lu J.H., Shen F. Elevated SHOX2 expression is associated with tumor recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann. Surg Oncol. 2013;20:S644–S649. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bergheim J., Semaan A., Gevensleben H., Groening S., Knoblich A., Dietrich J., Weber J., Kalff J.C., Bootz F., Kristiansen G., Dietrich D. Potential of quantitative SEPT9 and SHOX2 methylation in plasmatic circulating cell-free DNA as auxiliary staging parameter in colorectal cancer: a prospective observational cohort study. Br. J. Cancer. 2018;118:1217–1228. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0035-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Branchi V., Schaefer P., Semaan A., Kania A., Lingohr P., Kalff J.C., Schäfer N., Kristiansen G., Dietrich D., Matthaei H. Promoter hypermethylation of SHOX2 and SEPT9 is a potential biomarker for minimally invasive diagnosis in adenocarcinomas of the biliary tract. Clin. Epigenetics. 2016;8:133. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0299-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y.A., Zhou Y., Luo X., Song K., Ma X., Sathe A., Girard L., Xiao G., Gazdar A.F. SHOX2 is a Potent Independent Biomarker to Predict Survival of WHO Grade II-III Diffuse Gliomas. EBioMedicine. 2016;13:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun C., Liu X.H., Sun Y.R. MiR-223-3p inhibits proliferation and metastasis of oral squamous cell carcinoma by targeting SHOX2. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019;23:6927–6934. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201908_18732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baslan T., Morris J.P., Zhao Z., Reyes J., Ho Y.J., Tsanov K.M., Bermeo J., Tian S., Zhang S., Askan G., et al. Ordered and deterministic cancer genome evolution after p53 loss. Nature. 2022;608:795–802. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05082-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang M., Dong W., Xie R., Wu J., Su Q., Li W., Yao K., Chen Y., Zhou Q., Zhang Q., et al. HSF1 facilitates the multistep process of lymphatic metastasis in bladder cancer via a novel PRMT5-WDR5-dependent transcriptional program. Cancer Commun. 2022;42:447–470. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peng S., Chen X., Huang C., Yang C., Situ M., Zhou Q., Ling Y., Huang H., Huang M., Zhang Y., et al. UBE2S as a novel ubiquitinated regulator of p16 and beta-catenin to promote bone metastasis of prostate cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022;18:3528–3543. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.72629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Q., Liu S., Wang H., Xiao K., Lu J., Chen S., Huang M., Xie R., Lin T., Chen X. ETV4 Mediated Tumor-Associated Neutrophil Infiltration Facilitates Lymphangiogenesis and Lymphatic Metastasis of Bladder Cancer. Adv. Sci. 2023;10 doi: 10.1002/advs.202205613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang F., Xu D., Wang S., Wong C.K., Martinez-Fundichely A., Lee C.J., Cohen S., Park J., Hill C.E., Eng K., et al. Chromatin profiles classify castration-resistant prostate cancers suggesting therapeutic targets. Science. 2022;376 doi: 10.1126/science.abe1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y., Lieberman R., Pan J., Zhang Q., Du M., Zhang P., Nevalainen M., Kohli M., Shenoy N.K., Meng H., et al. miR-375 induces docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer by targeting SEC23A and YAP1. Mol. Cancer. 2016;15:70. doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0556-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mollet G., Salomon R., Gribouval O., Silbermann F., Bacq D., Landthaler G., Milford D., Nayir A., Rizzoni G., Antignac C., Saunier S. The gene mutated in juvenile nephronophthisis type 4 encodes a novel protein that interacts with nephrocystin. Nat. Genet. 2002;32:300–305. doi: 10.1038/ng996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lv C., Fu S., Dong Q., Yu Z., Zhang G., Kong C., Fu C., Zeng Y. PAGE4 promotes prostate cancer cells survive under oxidative stress through modulating MAPK/JNK/ERK pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;38:24. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1032-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

Data: All the data reported in this study will be shared by the lead contact upon request. This paper analyzes existing, publicly available data. These accession numbers for the datasets are listed in the key resources table.

-

•

Code: This study does not report any original code. Two PCa datasets were downloaded from the TCGA and GEO datasets (GSE35988).

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.