Highlights

-

•

The extraction process of mulberry leaf protein was optimized with the protein dissolution amount as the index;

-

•

The Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy of extracted mulberry leaf protein were measured;

-

•

The functional characteristics of protein extracted by the ultrasound-assisted cellulase degradation method were evaluated.

Keywords: Mulberry leaf, Protein, Extraction, Ultrasound, Cellulase

Abstract

The mulberry leaf protein extracted by ultrasound-assisted cellulase degradation (UACD) method was optimized with the protein dissolution amount (PDA) as the index. The Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and scanning electron microscopy of extracted mulberry leaf protein were measured. The functional characteristics of protein extracted by the UACD method were evaluated. Results showed that the extraction condition was optimized and adjusted to the following parameters: pH value of 7.20, ultrasound temperature of 35.00 °C, enzyme dosage of 4.20% and ultrasound time of 10.00 min. Under these optimized conditions, the experimental verification value of PDA was 13.87 mg/mL, which was approaching to the predicted value of 13.54 mg/mL. The analysis results of FTIR showed that after extraction by the UACD method, the mulberry leaf protein with the vibrational peak of ester carbonyl (C = O) absorption peak (1734.66 cm−1) disappeared. The α-helix content of protein extracted by the UACD decreased by 8.13%, and the β-turn and random coil content of protein increased by 20.22% and 18.79%, respectively, compared to that of the blank. The microstructure of mulberry leaf protein showed that the UACD method could break the dense structure of protein raw materials, reduce the average size of proteins and increase the specific surface area and roughness of proteins. According to the results of functional characteristics, the mulberry leaf protein extracted by the UACD method presented the highest enzymolysis properties and solubility, which was beneficial for the application in the food industry. In conclusion, the UACD method was a very effective way to extract protein from mulberry leaf.

1. Introduction

Mulberry leaf is one of the most commonly used medicinal and herbaceous traditional Chinese medicines [1], [2]. It has the functions including the regulation of blood pressure, vascular dysfunction and losing weight, which is described in the pharmacopoeia. Besides, mulberry leaf is also very popular as a healthy vegetable, especially in China [3]. Many researches showed that mulberry leaf was rich in various functional and active ingredients, such as protein, flavonoids, polyphenols, polysaccharides, etc. [4], [5], [1]. The content of crude protein in mulberry leaf is up to 24.70%, which is higher than that of common food raw materials such as oats (11.35%∼19.90%) and refined flour (12%) [5]. Therefore, the extraction of mulberry leaf protein is useful and valuable.

The alkali extraction and acid precipitation (AEAP) is a traditional method to extract protein from plants. However, some proteins are combined with sugar, especially cellulose in the green leaved plants and it limits the protein extraction yield. Nowadays, it has become an important way to improve the solubility of mulberry leaf proteins by removing a large amount of cellulose. Enzyme-assisted extraction can be used as an effective way to extract protein from plants [6] and it can increase protein extraction yield and maintain protein properties [7]. Research showed that the cellulase degradation method enhanced the protein extraction yields of seaweeds and it presented that the cellulase disrupted the sensitive carbohydrate matrix and increased the protein content in the extract compared to those of the non-enzymatic methods [8].

Besides, physically assisted processing methods can also significantly improve the extraction rate of target products. Ultrasound is wildly used in food physical processing to extract macromolecular active substances, especially protein [9] because of its easy operation, mild conditions, high security, etc [10]. Ultrasonication is a generally used method to assist protein solubilization due to the cell matrix being broken to improve the extractability [11]. It can effectively reduce the extraction time, improve the extraction rate and reduce the use of chemical reagents [12], [13]. Ultrasound mainly alters the water and hydrogen bonds of proteins through ultrasonic cavitation and mechanical effects, while also causing changes to secondary structures, which can increase the repulsion between proteins and thus it increases the protein solubility [14], [15]. Some researchers found that ultrasound was applied to facilitate sugar–protein separation and it separated the sugar–protein structure and did not induce damage to the product [16], [17]. Ultrasound can not only increase the protein extraction rate, but also can offer a lot of advantages over traditional enzymolysis [18], which increased the protein extraction rate further [19]. Research showed that under the optimum extraction condition, the protein extraction rate of mulberry leaf reached 16.06% and increased by at least 56.99% compared to one single extraction method [20]. However, little research focused on the mechanism of the ultrasound-assisted cellulase degradation (UACD) method for the extraction of mulberry leaf protein. Also, little report was found in the functional characteristics of protein extracted by the UACD method from the mulberry leaf.

Therefore, from the perspective of comprehensive utilization of mulberry leaf, the optimization of ultrasound-assisted cellulase degradation method on the extraction of mulberry leaf protein and its effect on the functional characteristics were investigated. It included three parts: (1) to optimize the process conditions of the UACD method on the protein dissolution amount (PDA) from the mulberry leaf using single-factor and response surface experimental design; (2) to reveal the mechanism of the UACD method on the PDA by analysis of protein structure; (3) to study the functional characteristics of protein extracted by the UACD method.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Fresh mulberry leaf was plucked from Silkworm Science Park of Chengde Medical University (Chengde, China) with a protein content of 23.75% (dry weight). Cellulase (activity of 10,000U/g), bovine serum albumin (standard reagent) and Foline-phenol reagent were bought from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. All other reagents used in the experiment were of analytical grade.

2.2. The extraction of mulberry leaf protein by alkali solution

The effects of the NaOH solvent concentration (0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 0.9%), temperature (50, 60, 70, 80, 90 °C), time (3, 3.5, 4, 4.5, 5 h) and material concentration (50, 60, 70, 80, 90 g/L) on the PDA of mulberry leaf were investigated. The operation steps were as follows: mulberry leaf powder was put in the alkali solution which was kept in a water bath with constant temperature. After extraction under the setting parameters, the sample was quickly centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected for determination of protein extraction rate with the PDA as index. The determination of PDA was using the method of Lowry’s [21] with the following standard curve: y = 0.4249x + 0.0037 (R2 of 0.9946).

2.3. The effects of UACD method on the PDA of mulberry leaf

2.3.1. Single-factor stepwise optimization of the extraction process

In order to optimize the extraction process of the UACD method on the PDA of mulberry leaf, a single-factor stepwise optimization experiment was conducted. The mulberry leaf powder was mixed with distilled water which was kept in a water bath of 60 °C to obtain the final material concentration of 70 g/L. Then the sample was pretreated by the UACD method with the ultrasound equipment purchased from Ningbo Scientz Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Ningbo, China; Model of SB-5200DT). The single-factor experiment was conducted with the following conditions: pH of 5, 6, 7, 8, 9; ultrasound temperature of 30, 35, 40, 45, 50 °C; cellulase dosage of 3, 4, 5, 6, 7%; ultrasound time of 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 min. After being pretreated by the UACD method, the sample was added with NaOH to reach the final alkali concentration of 0.5%. After being extracted for another 3.5 h, the sample was quickly cooled and centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected for the determination of protein content.

2.3.2. Optimization of extraction process by response surface experiment

According to the results of single-factor stepwise optimization test, the pH value (A), ultrasound temperature (B), cellulase dosage (C) and ultrasound time (D) were found to have significant influences on the PDA of mulberry leaf. A four-factor and three-level response surface experiment was used to optimize the extraction process of mulberry leaf protein. The actual and coded values for the independent variables were shown in Table 1. The factors with the same coded levels of −1, 0 and 1 indicated the actual value of pH value (6, 7, 8), ultrasound temperature (30, 35, 40 °C), cellulase dosage (3, 4, 5%) and ultrasound time (5, 10, 15 min), respectively. The PDA of mulberry leaf was set as response value (Y) to optimize the optimum extraction conditions.

Table 1.

Box-Behnken design and response results of the UACD method on PDA.

| Number | A | B | C | D | PDA(mg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 8.18 ± 0.37 |

| 2 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 10.37 ± 0.58 |

| 3 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 9.23 ± 0.37 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10.28 ± 0.37 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 10.89 ± 0.37 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 11.33 ± 0.37 |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 10.28 ± 0.37 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 11.42 ± 0.30 |

| 9 | −1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 8.44 ± 0.52 |

| 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | −1 | 10.89 ± 0.30 |

| 11 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8.97 ± 0.52 |

| 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10.8 ± 0.37 |

| 13 | 0 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 10.54 ± 0.74 |

| 14 | 0 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 10.54 ± 0.52 |

| 15 | 0 | −1 | 1 | 0 | 11.33 ± 0.37 |

| 16 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 11.24 ± 0.30 |

| 17 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 8.97 ± 0.52 |

| 18 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 0 | 10.02 ± 0.52 |

| 19 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8.62 ± 0.30 |

| 20 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 11.07 ± 0.52 |

| 21 | 0 | −1 | 0 | −1 | 10.89 ± 0.80 |

| 22 | 0 | 1 | 0 | −1 | 11.33 ± 0.37 |

| 23 | 1 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 10.89 ± 0.37 |

| 24 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 11.77 ± 0.30 |

| 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13.43 ± 0.37 |

| 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13.69 ± 0.52 |

| 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13.17 ± 0.74 |

2.4. Preparation of mulberry leaf protein

The mulberry leaf protein was extracted according to the results of the response surface experiment. Then the pH of the supernatant was adjusted to 4.0 with 4 mol/L HCl solution and centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 10 min. The precipitation was collected and dried to obtain mulberry leaf protein. Meanwhile, the mulberry leaf protein extracted without ultrasound (using the method of CD) and traditional AEAP method were also prepared. The protein contents of mulberry leaf extracted by different methods were determined using the equipment of automatic kjeldahl nitrogen determination apparatus (K-360, Buchilaboratory equipment trading (Shanghai) LTD, China).

2.5. Structural characterization of the extracted protein of mulberry leaf

2.5.1. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of mulberry leaf protein

The effects of different extracted methods on the intermolecular chemical bonds of mulberry leaf protein were measured by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Nicolet IS50 spectrum instrument, Thermo Electron Corporation, USA). After being diluted by one-tenth of potassium bromide powder, the mulberry leaf protein powder was pressed into 1–2 mm slices. The scanning wavelength was set between 4000 cm−1 and 525 cm−1 with 36 scans using pure potassium bromide powder as the background.

2.5.2. Scanning electron microscopy of mulberry leaf protein

The mulberry leaf protein was coated with a conductive layer. The microstructure was determined with a Hitachi S-4800 scanning electron microscope (Hitachi High Technologies, Tokyo, Japan) at an acceleration voltage of 15 kV. The mulberry leaf proteins extracted by AEAP and cellulase degradation (CD) methods were also measured.

2.6. Evaluation of functional activity

2.6.1. Enzymolysis properties

The mulberry leaf proteins extracted by different methods were hydrolyzed by alcalase according to the method of Xu et al. [22] with some modifications. The enzymatic conditions were set as the follows: protein concentration of 30 g/L, pH of 9.0, temperature of 50 °C, enzyme dosage of 5% E/S and enzymatic time of 40 min. The pH was maintained at constant value with 1 mol/L NaOH. After enzymolysis, the volume of NaOH solution consumed was recorded. The mixture was put in boiled water for 10 min to inactivate the enzyme and the supernatant was collected for further analysis. The enzymolysis properties of the proteins were evaluated according to the peptide concentration in hydrolysate, which was determined by the method of Lowry’s [21]. And the DH of mulberry leaf protein was calculated using pH-stat method [23] by the following equation (1):

| (1) |

Where, V represented the volume of NaOH solution consumed (mL); N represented the concentration of NaOH solution, which was 1 mol/L in this paper; represented the average dissociation degree of the α-NH2 groups at a certain pH and temperature, which was 0.985. M represented the mass of protein in sample (g); represented the total number of peptide bonds contained in each molecule of substrate protein, which was related to the protein category and it was 7.883 mmol/g for mulberry leaf protein [24].

2.6.2. Solubility and solubility stability

Solubility was determined according to the method of Wu et al. [25] with some modifications [26]. The mulberry leaf protein powder was reconstituted with distilled water. Aliquots were centrifuged at 700 g for 10 min and the supernatants were carefully pipetted. After being dried in an oven (101-1AB, Tianjin Taisite Instrument Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China), the weight of the solution (Wo) and that of the supernatant (Ws) were recorded. The solubility was calculated according to the following formula (2):

| (2) |

The solubility stability of the sample was measured according to the method of Zhang et al [27] with some modifications. After being mixed with distilled water, the mulberry leaf protein was placed in a refrigerator at 4 °C for five days, and the solubility was measured again.

2.7. Statistical analysis

The results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with SPSS 23.0 software (IBM Corporation, NY, USA). The data was stated using mean and standard deviation and the significant differences were at p ≤ 0.05. All the experiments were done in triplicate.

3. Results and discussion

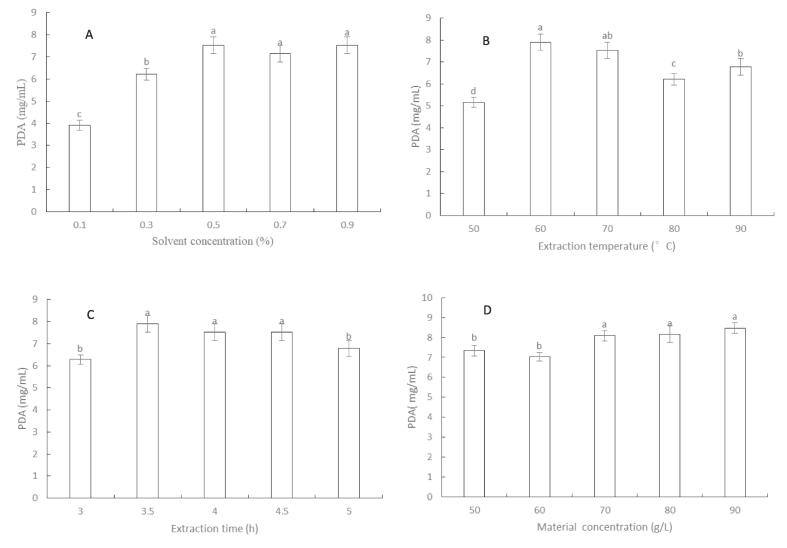

3.1. The extraction of mulberry leaf protein by alkali solution

The effects of solvent concentration (NaOH), temperature, time and material concentration on the PDA of mulberry leaf were shown in Fig. 1. The PDA of mulberry leaf increased with the rise of extraction solvent concentration and reached the highest value of 7.53 mg/mL at the solvent concentration of 0.5%. It has no significant difference (p > 0.05) compared to that of 0.7% and 0.9% (Fig. 1A). The PDA of mulberry leaf improved with the increase in extraction temperature and reached the highest at 60 °C with the value of 7.91 mg/mL and then it presented a downward trend (Fig. 1 B). The PDA of mulberry leaf increased with the extension of extraction time and reached its highest value at 3.5 h and the PDA of mulberry leaf was 7.91 mg/mL, which was the same as that of protein under optimum temperature (Fig. 1C). The PDA of mulberry leaf went up with the increase in the material liquid ratio and reached its highest value of 8.10 mg/mL at material concentration of 70 g/L (Fig. 1D). Therefore, the extraction process of mulberry leaf protein by alkali solution was screened using the solvent concentration (NaOH) of 0.5%, extraction temperature of 60 °C, extraction time of 3.5 h and material concentration of 70 g/L.

Fig. 1.

The effects of alkali extraction conditions: (A) solvent concentration; (B) extraction temperature; (C) extraction time; (D) material concentration on the PDA of mulberry leaf.

3.2. The effects of the UACD method on the PDA of mulberry leaf

3.2.1. Single-factor stepwise optimization

The effects of the UACD method on the PDA of mulberry leaf were shown in Fig. 2. From Fig. 2A it can be seen that with the increase in pH value, the PDA of mulberry leaf increased significantly (p < 0.05). The PDA of mulberry leaf went up with the increase in pH value and reached the highest at the pH value of 7 with the PDA of 8.62 mg/mL. Then the PDA of mulberry leaf gradually tends to maintain stability. The reason for this phenomenon was that the alkaline condition could increase the protein solubility, but it also could inactive cellulose, which led to an appropriate pH value of 7 [28].

Fig. 2.

The effects of ultrasound-assisted cellulase degradation method on the PDA of mulberry leaf with the extraction conditions: (A) pH value; (B) ultrasound temperature; (C) enzyme dosage; (D) ultrasound time.

From Fig. 2B, it could be seen that the PDA of mulberry leaf protein showed a trend of increasing at first and then decreasing. When the temperature of ultrasound extraction was low, it was not conducive to the cavitation effect of ultrasound. Also, if the ultrasound temperature was too high, it would cause protein denaturation, damage the spatial structure, and decrease the solubility of protein molecules due to mutual binding. At the same time, too high extraction temperature would also reduce the cavitation effect of ultrasound, which was not conducive to protein dissolution [29]. As the ultrasound temperature went up, the PDA of mulberry leaf reached its highest at 35 °C with the PDA value of 8.97 mg/mL and showed a decreasing trend afterwards. When the reaction temperature exceeded the optimal cellulose temperature, the activity of cellulose significantly decreased (p < 0.05), which resulted in a decrease in the PDA of mulberry leaf.

As shown in Fig. 2C, the cellulase dosage had a significant influence (p < 0.05) at the PDA of mulberry leaf and the highest value appeared at the cellulose dosage of 4% with the value of 9.85 mg/mL and then it kept stable afterward. Some proteins in mulberry leaf were enveloped by the cell wall and those proteins could not be fully dissolved. Cellulose could damage the plant cell wall and make the protein in the cell more easily released and thus increasing the PDA of mulberry leaf [30].

As shown in Fig. 2D, with the extension of ultrasound time, the PDA of mulberry leaf showed a trend of increasing at first and then it decreasd. An appropriate ultrasound time was beneficial for the generation of ultrasound cavitation, which could promote the interaction between cellulose and substrate and improve the dissolving of protein. When the ultrasound time exceeded 10 min, the PDA of mulberry leaf showed the highest value of 11.33 mg/mL and then it decreased. The reason might be attributed to the excessive shear force generated by long ultrasonic time treatment and the prolonged ultrasound cavitation and the mechanical effect caused amino acid side chains to undergo denaturation, increase in hydrophobicity or structural changes in condensation with other molecules [31].

3.2.2. Optimization of response surface methodology

3.2.2.1. Response surface test results and analysis of variance

According to the design principle of the Box Behnken experiment, a four-factor and three-level response surface experiment was designed with the pH value (A), ultrasound temperature (B), enzyme dosage (C) and ultrasound time (D) as independent variables. The PDA of mulberry leaf was set as the response value. The experimental design and result were shown in Table 1. Multiple regression equation analysis was conducted on the data in Table 2, and the response surface variables were established. The quadratic regression equation obtained by fitting the response value was as follows: the PDA of mulberry leaf protein (mg/mL) = 13.43 + 0.9183A + 0.1825B + 0.3142C + 0.0300D-0.2850AB + 0.3500AC-0.1550AD-0.0225BC + 0.1100BD + 0.1750CD-2.58A2-1.24B2-1.28C2-1.07D2.

Table 2.

Box-Behnken design of the UACD method on the variance analysis and p-value.

| Source | Sum of square | Df | Mean square | F-value | p-value | significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 49.86 | 14 | 3.56 | 43.75 | <0.0001 | ** |

| A | 10.12 | 1 | 10.12 | 124.31 | <0.0001 | ** |

| B | 0.3997 | 1 | 0.3997 | 4.91 | 0.0468 | * |

| C | 1.18 | 1 | 1.18 | 14.55 | 0.0025 | ** |

| D | 0.0108 | 1 | 0.0108 | 0.1327 | 0.7220 | |

| AB | 0.3249 | 1 | 0.3249 | 3.99 | 0.0689 | |

| AC | 0.4900 | 1 | 0.4900 | 6.02 | 0.0304 | * |

| AD | 0.0961 | 1 | 0.0961 | 1.18 | 0.2986 | |

| BC | 0.0020 | 1 | 0.0020 | 0.0249 | 0.8773 | |

| BD | 0.0484 | 1 | 0.0484 | 0.5945 | 0.4556 | |

| CD | 0.1225 | 1 | 0.1225 | 1.50 | 0.2435 | |

| A2 | 35.51 | 1 | 35.51 | 436.23 | <0.0001 | ** |

| B2 | 8.16 | 1 | 8.16 | 100.19 | <0.0001 | ** |

| C2 | 8.73 | 1 | 8.73 | 107.20 | <0.0001 | ** |

| D2 | 6.14 | 1 | 6.14 | 75.42 | <0.0001 | ** |

| Residual | 0.9769 | 12 | 0.0814 | |||

| Lack of fit | 0.8417 | 10 | 0.0842 | 1.25 | 0.5252 | Not significant |

| Pure error | 0.1352 | 2 | 0.0676 | |||

| Total error | 50.83 | 26 |

According to the experimental results in Table 2, regression analysis was conducted on the model of the mulberry leaf protein extraction process using the PDA of mulberry leaf as the response value. From Table 2 it can be seen that A, C, A2, B2, C2 and D2 had a extremely significant impact (p < 0.01) on the PDA of mulberry leaf, while that of B and AC had a significant impact (p < 0.05). The F value of this model was 43.75 and the impact was extremely significant (p < 0.01). The mean square of lack of fit was 0.5252 and the impact was not significant (p > 0.05), indicating that the predicted model fit well with the actual situation with small errors. The relationships between the observed and predicted values of PDA of mulberry leaf were shown in Fig. 3, and it showed an acceptable level of agreement. This model could be used to optimize the process reference for the extraction of protein by the UACD method of mulberry leaf. The correlation coefficient R2 of 0.9808 indicates that 98.08% of the change could be explained by the independent variable. According to F-test and p value, the contribution of the four factors to the PDA of mulberry leaf was in the following order: A > C > B > D, that is, pH > enzyme dosage > ultrasonic temperature > ultrasonic time.

Fig. 3.

Relationship between the observed and predicted values of the PDA of mulberry leaf.

The response surface graph based on the regression model was shown in Fig. 4. The interaction between the four factors was not a simple linear relationship, and the interaction between the two factors was positively correlated with the steepness of the surface graph. Therefore, the greater the correlation between the two factors in the surface graph, the steeper the distribution of the surface graph. As shown in the figure, the interaction between pH value and enzyme dosage had a significant impact on the PDA of mulberry leaf, which was also proved in Table 2 with the p value of pH value (A) and enzyme dosage (C) less than 0.05. The ralationship between pH value and ultrasound temperature or ultrasound time had certain interactions. In the results, the factor involving pH value presented interactions, which also proved that pH value was the most contribution of the four factors to the PDA of mulberry leaf.

Fig. 4.

Response surface plots for the interactive effects of (A) pH value, (B) ultrasound temperature, (C) enzyme dosage and (D)ultrasound time on the PDA of mulberry leaf. Interaction between (I) pH and ultrasound temperature; (II) pH and enzyme dosage; (III) pH and ultrasound time; (IV) ultrasound temperature and enzyme dosage; (V) ultrasound temperature and ultrasound time; (VI) enzyme dosage and ultrasound time.

3.2.2.2. Validation of the optimal extraction process of protein of mulberry leaf

Through the Box Behnken experiment analysis, the optimal extraction process conditions for mulberry leaf protein were obtained as follows: pH value 7.18, ultrasound temperature 35.26 °C, enzyme dosage 4.15%, ultrasound time 10.08 min. Under these optimized conditions, a theoretically soluble amount of 13.54 mg/mL mulberry leaf protein can be obtained. Adjusting the pH value to 7.20, the ultrasound temperature to 35.00 °C, the enzyme dosage to 4.20%, and the ultrasound time to 10.00 min, the experimental validation was carried out. The PDA of mulberry leaf obtained under the adjusted conditions was 13.87 mg/mL and it was very close to the theoretical value. This proved that the fitting degree of the experiment was good, and the model had good predictive and analytical ability. Therefore, the UACD method for extracting mulberry leaf protein is an excellent extraction method.

3.3. The protein content of mulberry leaf protein extracted by different methods

The protein content of mulberry leaf protein extracted by different methods was shown in Fig. 5. The content of mulberry leaf protein extracted by AEAP was 51.41%. The content of mulberry leaf protein extracted by UACD was the highest with the value of 62.69% which was 21.94% higher than that extracted by AEAP. These results indicated that the UACD method was an effective way to extract protein of mulberry leaf.

Fig. 5.

Effects of different extraction methods on the protein content of mulberry leaf protein.

3.4. The structural characterization of mulberry leaf protein

3.4.1. FTIR of mulberry leaf protein

The effects of the UACD method on the FTIR of mulberry leaf protein were shown in Fig. 6. The characteristic absorption peaks of protein represented different chemical bonds [32]. The absorption peak at 1734.66 cm−1 and 1632.45 cm−1 belonged to the double bond stretching vibration zone (2000–1500 cm−1). The absorption peak of 1734.66 cm−1 was the ester carbonyl (C=O) absorption vibration frequency. After extraction by the UACD method, the protein with the vibrational peak of 1734.66 cm−1 disappeared, which showed that ultrasound might break the cellulose-protein agglomerates. The disappearance of the C=O absorption peak also occurred at the protein extracted by the AEAP method or CD method.

Fig. 6.

The effects of different pretreatment methods on the FTIR of mulberry leaf protein.

The changes of amide I (1700–1600 cm−1 wavelength), II (1530–1550 cm−1 wavelength) and III (1260–1300 cm−1) [33] were observed at the protein extracted by the UACD method. And the peak position of amide I was normally used to analyze the secondary structure of the protein [34]. The absorption peak of amide I switched to 1635.34, 1635.34 and 1639.68 cm−1 after being pretreated by the AEAP, CD and UACD methods, respectively, in contrast to that of native protein with the absorption peak of 1632.45 cm−1. The secondary structures of protein extracted by different methods were analyzed and the results were shown in Table 3. The α-helix content of protein extracted by ultrasound method decreased significantly (p < 0.05) with the value of 16.62% and decreased by 8.13% compared to that of the blank. On the contrary, the β-turn and random coil content of protein extracted by ultrasound method increased with the amplitude of 20.22% and 18.79%, respectively. That of β-sheet did not change significantly (p > 0.05). These results suggested that the protein extracted by UACD method made the tight α-helix structure unfold and formed new β-sheet and random coil structure. These findings were similar to the results of Jin et al. [35], who reported that pretreatment decreased the α-helix content by 16.1% and increased the random coil content by 3.6% of rapeseed protein. Differently, the research of Frydenberg et al. [36] showed that high-intensity ultrasound treatment on the whey protein isolates had no significant change (p > 0.05) on the secondary structure of the protein. These differences in the secondary structure content of protein might be related to the protein category, ultrasound parameter, protein initial structure, etc.

Table 3.

Effect of the UACD method on the secondary structure of mulberry leaf protein (%).

| Secondary structure | Blank | AEAP | CD | UACD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-helix | 18.09 ± 0.04a | 17.96 ± 0.03b | 17.87 ± 0.03b | 16.62 ± 0.09c |

| β-sheet | 37.72 ± 0.58abd | 37.05 ± 0.36be | 36.59 ± 0.36ce | 38.03 ± 0.06d |

| β-turn | 24.28 ± 0.63a | 25.40 ± 0.33b | 25.89 ± 0.30b | 29.19 ± 0.27c |

| Random coil | 19.90 ± 0.05a | 19.59 ± 0.01b | 19.65 ± 0.02b | 16.16 ± 0.13c |

Different letters means significant effect (p < 0.05) of the same line.

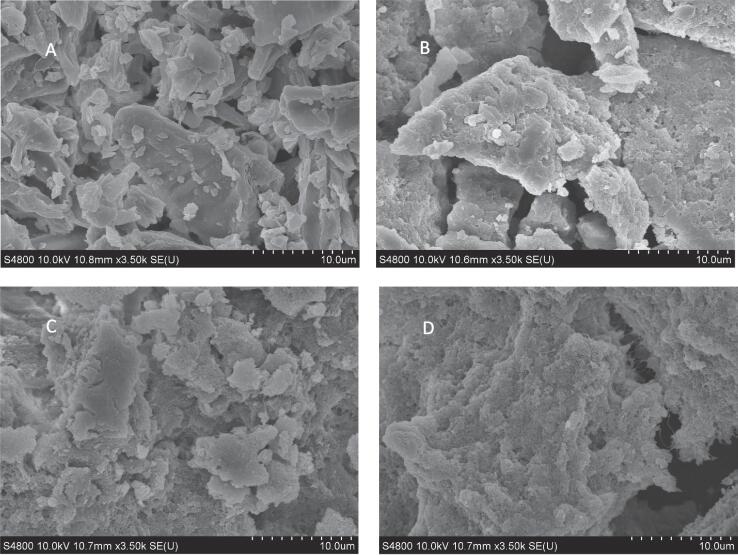

3.4.2. Microstructure of mulberry leaf protein

The effects of the UACD method on the microstructure of PDA of mulberry leaf were shown in Fig. 7. The microstructure of native PDA was tight and molecules stacked on top of each other and lack of gaps. And there were sheet structures and many scattered small fragments with regular edges (Fig. 7A). After extraction, the protein structure with small fragments was reduced and aggregated into large protein molecules with disordered edges. As shown in Fig. 7B, the protein extracted by the traditional AEAP method presented a large and compact protein structure. After being extracted by the CD method, the protein molecules formed relatively small fragments compared to that of Fig. 7B and the edges of the protein were irregular (Fig. 7C). Ultrasound-assisted extraction increased irregularity at the edges of protein molecules and the cavity structure emerged between molecules. It also could break the dense structure of protein raw materials, reduce the average size of proteins and increase the specific surface area and roughness of proteins (Fig. 7D). The protein surface was more uniform and continuous than that without ultrasound [37]. The loose and porous structure of proteins were beneficial for their application in the food industry, especially in enzymolysis [38]. These phenomena were consistent with that of Xiong et al. [39] who found that compared with untreated pea protein isolate, the samples which had been ultrasonicated exhibited smaller and more regular fragments with the increase in ultrasound amplitude.

Fig. 7.

The effects of different pretreatment methods on the microstructure of mulberry leaf protein. (A) Blank: native mulberry leaf protein; (B) Mulberry leaf protein extracted by AEAP method; (C) Mulberry leaf protein extracted by CD method; (D) Mulberry leaf protein extracted by UACD method.

3.5. Functional characteristics on the PDA of mulberry leaf

3.5.1. Enzymolysis properties of mulberry leaf protein

The enzymolysis properties of mulberry leaf protein were evaluated according to the DH of concentration of mulberry leaf protein and peptide concentration in the enzymatic hydrolysate. The effects of the UACD method on the enzymolysis properties of mulberry leaf protein were shown in Fig. 8. Under the same protein content conditions, different protein extraction methods had different enzymolysis properties. Fig. 8A showed that the peptide extracted by UACD method presented the highest value of 22.81%, and increased by 11.49% compared to that of the blank (native mulberry leaf protein). From Fig. 8B it could be seen that the protein extracted by the AEAP method presented a higher peptide concentration with the value of 4.91 mg/mL and increased by 15.59% compared to that of the blank after enzymolysis. The CD method and UACD method went a step further to increase the concentration of peptides in enzymolysis products with the value of 5.49 and 6.32 mg/mL. The results of peptide concentration were in line with the results of DH of mulberry leaf protein. Among all the extraction methods, the protein extracted by the UACD method showed the highest enzymolysis properties. This result was also consistent with that of the microstructure of mulberry leaf protein (Fig. 7). The increase in the specific surface area of protein molecules increased its exposure chance to protease and this enhanced the enzymolysis properties of the protein further [38], [40].

Fig. 8.

Effects of different extraction methods on the enzymolysis properties of mulberry leaf protein. (A) the DH of mulberry leaf protein; (B) the peptide concentration in protein-hydrolysate from mulberry leaf.

3.5.2. Solubility and solubility stability of mulberry leaf protein

The protein solubility and solubility stability of mulberry leaf protein extracted by different methods were shown in Fig. 9. After extraction of the traditional AEAP method, the solubility of protein increased by 9.45% with the blank of 69.97%. The protein extracted by the CD method showed a higher solubility value of 80.04% and that extracted by the UACD method showed the highest value, which increased by 17.33% compared to that of the blank. A similar tendency was presented in the protein solubility stability of mulberry leaf protein. The mulberry leaf protein extracted by the UACD method showed the highest value of 76.43% with the blank of 64.90%. These results showed that the UACD method was beneficial for the solubility and solubility stability of the protein. The increase in solubility and solubility stability might be affected by the advanced structure (secondary structure and microstructure structure in Fig. 6 and Fig. 7, respectively) of protein extracted by different methods of mulberry leaf. It was consistent with the result of Lo et al. [41] whose research also showed that ultrasound increased the solubility of lupin protein across the pH profile.

Fig. 9.

Effects of different extraction methods on the solubility of mulberry leaf protein.

4. Conclusion

The extraction process of mulberry leaf protein by alkali solution was screened using the solvent concentration (NaOH solution) of 0.5%, extraction temperature of 60 °C, extraction time of 3.5 h and material concentration of 70 g/L. All the UACD extraction could improve the PDA of mulberry leaf significantly (p < 0.05) compared to that of the blank. Under the pH value of 7, ultrasound temperature of 35 °C, cellulose dosage of 4% and ultrasound time of 10 min, the PDA of mulberry leaf reached the highest according to the experimental results of single-factor stepwise optimization. The response surface experiment results showed that the ultimate condition was optimized and adjusted to the following parameters: pH value of 7.20, ultrasound temperature of 35.00 °C, enzyme dosage of 4.20% and ultrasound time of 10.00 min. Under these conditions, the experimental verification value of PDA was 13.87 mg/mL, which was approaching the predicted value of 13.54 mg/mL. The protein content of mulberry leaf protein extracted by UACD was the highest with the value of 62.69% which was 21.94% higher than that extracted by AEAP. The analysis results of FTIR showed that after being extracted by the UACD method, the protein with the vibrational peak of ester carbonyl (C = O) absorption peak (1734.66 cm−1) disappeared. The α-helix content of protein extracted by the UACD method decreased by 8.13%, and the β-turn and Random coil content of protein increased by 20.22% and 18.79%, respectively, compared to that of the blank. The microstructure of mulberry leaf protein showed that the UACD method could break the dense structure of protein raw materials, reduce the average size of proteins and increase the specific surface area and roughness of proteins. According to the results of functional characteristics, the protein extracted by UACD showed the highest enzymolysis properties and solubility, which was beneficial for the application in the food industry.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Wei Fan: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Hanyi Duan: Methodology, Investigation, Validation. Xiaolan Ren: Methodology, Investigation, Validation. Xiaoyan Guo: Data curation, Software. Yachao Zhang: Data curation, Software. Jisheng Li: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Fengying Zhang: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Juan Chen: Formal analysis, Validation. Xue Yang: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the fund of Science and Technology Project of Hebei Education Department (BJK2023035); Technology Innovation Guidance Project-Science and Technology Work Conference of Hebei Provincial Department of Science and Technology (the year of 2020) and Chengde Medical University Project (202117; 201902). We thank Hebei Key Laboratory of Nerve Injury and Repair for providing the necessary experimental conditions.

References

- 1.Li Q., Liu F., Liu J., Liao S., Zou Y. Mulberry leaf polyphenols and fiber induce synergistic antiobesity and display a modulation effect on gut microbiota and metabolites. Nutrients. 2019;11:1017. doi: 10.3390/nu11051017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ge Q., Chen L., Tang M., Zhang S., Gao L., Ma S., Liu L., Kong M., Yao Q., Chen K., Feng F. Analysis of mulberry leaf components in the treatment of diabetes using network pharmacology. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018;833:50–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ann J.Y., Eo H., Lim Y. Mulberry leaves (Morus alba L.) ameliorate obesity-induced hepatic lipogenesis, fibrosis, and oxidative stress in high-fat diet-fed mice. Genes Nutr. 2015;10:46. doi: 10.1007/s12263-015-0495-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao X., Fu Z., Yao M., Cao Y., Zhu T., Mao R., Huang M., Pang Y., Meng X., Li L., Zhang B., Li Y., Zhang H. Mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaf polysaccharide ameliorates insulin resistance-and adipose deposition-associated gut microbiota and lipid metabolites in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022;10:617–630. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong Y., Song B., Zheng C., Zhang S., Yan Z., Tang Z., Kong X., Duan Y., Li F. Flavonoids from mulberry leaves alleviate lipid dysmetabolism in high fat diet-fed mice: Involvement of gut microbiota. Microorganisms. 2020;8:860. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8060860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bleakley S., Hayes M. Algal proteins: extraction, application, and challenges concerning production. Foods. 2017;6:33. doi: 10.3390/foods6050033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wijesinghe W., Jeon Y.J. Enzyme-assistant extraction (EAE) of bioactive components: a useful approach for recovery of industrially important metabolites from seaweeds: a review. Fitoterapia. 2012;83:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vásquez V., Martínez R., Bernal C. Enzyme-assisted extraction of proteins from the seaweeds Macrocystis pyrifera and C hondracanthus chamissoi: Characterization of the extracts and their bioactive potential. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019;31:1999–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gani A., ul Ashraf Z., Noor N., Ahmed Wani I. Ultrasonication as an innovative approach to tailor the apple seed proteins into nanosize: Effect on protein structural and functional properties. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry. 2022;86 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang G., Chen S., Dai C., Sun L., Sun W., Tang Y., Xiong F., He R., Ma H. Effects of ultrasound on microbial growth and enzyme activity. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;37:144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahman M.M., Lamsal B.P. Ultrasound-assisted extraction and modification of plant-based proteins: Impact on physicochemical, functional, and nutritional properties. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021;20(2):1457–1480. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding Y., Ma H., Wang K., Azam S.M.R., Wang Y., Zhou J., Qu W. Ultrasound frequency effect on soybean protein: Acoustic field simulation, extraction rate and structure. LWT-Food Science and Technology. 2021;145 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Civan M., Kumcuoglu S. Green ultrasound-assisted extraction of carotenoid and capsaicinoid from the pulp of hot pepper paste based on the bio-refinery concept. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2019;113 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J., Liu Q., Chen Q., Sun F., Liu H., Kong B. Synergistic modification of pea protein structure using high-intensity ultrasound and pH-shifting technology to improve solubility and emulsification. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;88 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen L., Zhang S.-B. Structural and functional properties of self-assembled peanut protein nanoparticles prepared by ultrasonic treatment: Effects of ultrasound intensity and protein concentration. Food Chem. 2023;413 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.135626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu J., Yu X., Liu Y. Effect of ultrasound on mill starch and protein in ultrasound-assisted laboratory-scale corn wet-milling. J. Cereal Sci. 2021;100 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guraya H.S., James C. Deagglomeration of rice starch-protein aggregates by high-pressure homogenization. Starch-Stärke. 2002;54:108–116. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umego E.C., He R., Ren W., Xu H., Ma H. Ultrasonic-assisted enzymolysis: Principle and applications. Process Biochem. 2021;100:59–68. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang X., Li Y., Li S., Oladejo A.O., Wang Y., Huanga S., Zhou C., Ye X., Ma H., Duan Y. Effects of ultrasound-assisted α-amylase degradation treatment with multiple modes on the extraction of rice protein. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;40:890–899. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu H., Zhang Y. Study on Cellulase-ultrasonic Assisted Extraction of Protein from Mulberry Leaves. Farm Products Processing. 2022;12:40–46. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowry O.H., Rosebrough H.J., Farr A.L., Randall R.J. Protein measurement with Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu B., Yuan J., Wang L., Lu F., Wei B., Azam R.S.M., Ren X., Zhou C., Ma H., Bhandari B. Effect of multi-frequency power ultrasound (MFPU) treatment on enzyme hydrolysis of casein. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;63 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adler-Nissen J. Elsevier Applied Science Publishers; London: 1986. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Food Proteins. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jia M., Fan W., Li N., Wang B., Yang X., Xia A., Yang G., Li J. Preparation of Mulberry Leaf Protein ACE Inhibitory Peptide by Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Science of Sericulture. 2021;47(4):0351–0357. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu S., Li G., Xue Y., Ashokkumar M., Zhao H., Liu D., Zhou P., Sun Y., Hemar Y. Solubilisation of micellar casein powders by high-power ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;67 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao X., Fan X., Shao X., Cheng M., Wang C., Jiang H., Zhang X., Yuan C. Modifying the physicochemical properties, solubility and foaming capacity of milk proteins by ultrasound-assisted alkaline pH-shifting treatment. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;88 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang D., Wu Z., Ruan J., Wang Y., Li X., Xu M., Zhao J., Lin H., Liu P., Wang Z., Li H. Effects of lysine and arginine addition combined with high-pressure microfluidization treatment on the structure, solubility, and stability of pork myofibrillar proteins. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022;172 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sert D., Rohm H., Struck S. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Protein from Pumpkin Seed Press Cake: Impact on Protein Yield and Techno-Functionality. Foods. 2022;11:4029. doi: 10.3390/foods11244029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pan-utai W., Pantoa T., Roytraku S., Praiboon J., Kosawatpat P., Tamtin M., Thongdang B. Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction and Antioxidant Potential of Valuable Protein from Ulva rigida Macroalgae. Life. 2023;13:86. doi: 10.3390/life13010086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rakhmawati R., Sofiana A., Indariyanti N., Bokau R.J.M. Decreasing of Crude Fibre in Indigofera Leaves Flour Hydrolysed with Cellulase Enzyme as a Source of Feed Protein. C. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2022;1012 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X., Tang C., Li B., Yang X., Li L., Ma C. Effects of high-pressure treatment on some physicochemical and functional properties of soy protein isolates. Food Hydrocoll. 2008;22:560–567. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ambrico P.F., Amodeo A., Girolamo P.D., Spinelli N. Sensitivity analysis of differential absorption lidar measurements in the mid-infrared region. Appl. Opt. 2000;39:6847–6865. doi: 10.1364/ao.39.006847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zandomeneghi G., Krebs M.R.H., McCammon M.G., Fändrich M. FTIR reveals structural differences between native β-sheet proteins and amyloid fibrils. Protein Sci. 2004;13:3314–3321. doi: 10.1110/ps.041024904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kong J., Yu S. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic analysis of protein secondary structures. Acta Biochim. Biophy. Sin. 2007;39:549–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2007.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jin J., Ma H., Wang W., Luo M., Wang B., Qu W., He R., Owusua J., Li Y. Effects and mechanism of ultrasound pretreatment on rapeseed protein enzymolysis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016;96:1159–1166. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.7198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frydenberg R.P., Hammershøj M., Andersen U., Greve M.T., Wiking L. Protein denaturation of whey protein isolates (WPIs) induced by high intensity ultrasound during heat gelation. Food Chem. 2016;192:415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song J., Jiang L., Qi M., Li L., Xu M., Li Y., Zhang D., Wang C., Chen S., Li H. Study of ultrasonic treatment on the structural characteristics of gluten protein and the quality of steamed bread with potato pulp. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023;92 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang X., Li Y., Li S., Oladejo A.O., Ruan S., Wang Y., Huang S., Ma H. Effects of ultrasound pretreatment with different frequencies and working modes on the enzymolysis and the structure characterization of rice protein. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;38:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiong T., Xiong W., Ge M., Xia J., Li B., Chen Y. Effect of high intensity ultrasound on structure and foaming properties of pea protein isolate. Food Res. Int. 2018;109:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang X., Li Y., Li S., Ren X., Oladejod A.O., Lu F., Ma H. Effects and mechanism of ultrasound pretreatment of protein on the Maillard reaction of protein-hydrolysate from grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;64 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.104964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lo B., Kasapis S., Farahnaky A. Effect of low frequency ultrasound on the functional characteristics of isolated lupin protein. Food Hydrocoll. 2022;124 [Google Scholar]