ABSTRACT

Methanothrix is widely distributed in natural and artificial anoxic environments and plays a major role in global methane emissions. It is one of only two genera that can form methane from acetate dismutation and through participation in direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET) with exoelectrogens. Although Methanothrix is a significant member of many methanogenic communities, little is known about its physiology. In this study, transcriptomics helped to identify potential routes of electron transfer during DIET between Geobacter metallireducens and Methanothrix thermoacetophila. Additions of magnetite to cultures significantly enhanced growth by acetoclastic methanogenesis and by DIET, while granular activated carbon (GAC) amendments impaired growth. Transcriptomics suggested that the OmaF-OmbF-OmcF porin complex and the octaheme outer membrane c-type cytochrome encoded by Gmet_0930, were important for electron transport across the outer membrane of G. metallireducens during DIET with Mx. thermoacetophila. Clear differences in the metabolism of Mx. thermoacetophila when grown via DIET or acetate dismutation were not apparent. However, genes coding for proteins involved in carbon fixation, the sheath fiber protein MspA, and a surface-associated quinoprotein, SqpA, were highly expressed in all conditions. Expression of gas vesicle genes was significantly lower in DIET- than acetate-grown cells, possibly to facilitate better contact between membrane-associated redox proteins during DIET. These studies reveal potential electron transfer mechanisms utilized by both Geobacter and Methanothrix during DIET and provide important insights into the physiology of Methanothrix in anoxic environments.

IMPORTANCE

Methanothrix is a significant methane producer in a variety of methanogenic environments including soils and sediments as well as anaerobic digesters. Its abundance in these anoxic environments has mostly been attributed to its high affinity for acetate and its ability to grow by acetoclastic methanogenesis. However, Methanothrix species can also generate methane by directly accepting electrons from exoelectrogenic bacteria through direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET). Methane production through DIET is likely to further increase their contribution to methane production in natural and artificial environments. Therefore, acquiring a better understanding of DIET with Methanothrix will help shed light on ways to (i) minimize microbial methane production in natural terrestrial environments and (ii) maximize biogas formation by anaerobic digesters treating waste.

KEYWORDS: Methanothrix, direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET), methane, magnetite, granular activated carbon (GAC), archaea, Geobacter, cytochromes, acetate

INTRODUCTION

Methanothrix (formerly Methanosaeta) species, arguably the most prodigious methanogens on earth, substantially contribute to the production of atmospheric methane and the conversion of wastes to methane biofuel (1). Species from this genus are frequently the most abundant methanogens in methanogenic terrestrial environments where soluble electron acceptors such as sulfate and nitrate are absent or negligible, for example, in natural wetlands and flooded rice paddy soils, as well as in many anaerobic digester systems (2 - 8). Methanothrix species are also important members of the methanogenic community in Arctic and Antarctic sediments (9 - 11), and scientists are particularly concerned with increases in methane production linked to melting permafrost in these polar terrestrial sediments as this will lead to a positive feedback loop that will further exacerbate climate change (12 - 14).

Methanothrix are one of only two methanogenic genera that can utilize acetate as a substrate for methanogenesis (1). Unlike the other acetoclastic methanogenic genus, Methanosarcina, Methanothrix have an extremely high affinity for acetate and generally maintain acetate at levels too low (μM range) for their competitors to metabolize (15). This ability to metabolize acetate at the low in situ levels found in most sediments and conventional mesophilic digesters is an important physiological capability, because acetate is a precursor for approximately two-thirds of the methane produced in terrestrial environments (1, 16) and is also an important intermediate in anaerobic digesters (17, 18).

Clearly, the importance of acetate as a methane precursor demonstrates the central role of Methanothrix in carbon and electron flow in many methanogenic environments. However, it has also been found that Methanothrix species can reduce CO2 to methane by accepting electrons from exoelectrogenic bacteria via direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET) (4, 19), and this is likely to further increase their contribution to methane production in anoxic environments. Although Methanothrix species are predominant members of many methanogenic communities, little is known about their physiology (1, 20 - 23).

Methanothrix is considered a strictly acetoclastic methanogen; however, its genome contains genes from the CO2 reduction pathway which is used by hydrogenotrophic methanogens for growth on H2/CO2 and formate (1). Studies of Methanothrix harundinacea growing in co-culture with Geobacter metallireducens showed that it could convert 14C-labelled CO2 to 14C-methane, providing evidence that Methanothrix carries out CO2 reduction during DIET (4). In addition, CO2 reduction pathway genes were highly expressed by Methanothrix species growing by DIET in flooded rice paddy soils (2), anaerobic digesters treating waste (4, 24), and on the surface of cathodes in bioelectrochemical systems (25, 26). In a similar manner, acetoclastic Methanosarcina species growing by DIET with exoelectrogens highly expressed CO2 reduction genes (27 - 29).

In addition to Methanothrix' high affinity for acetate (30), another feature that would make Methanothrix a strong competitor in low-nutrient environments is the ability to fix CO2. All known Methanothrix species have genes coding for a RuBisCO-mediated reductive hexulose phosphate (RHP) pathway that forms formaldehyde as an intermediate (31, 32). They also have genes for a formaldehyde-activating enzyme (Fae), an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of formaldehyde into 5,10-methylenetetrahydromethanopterin, an intermediate in the methanogenic CO2 reduction pathway. Metatranscriptomic data demonstrated that Methanothrix was highly expressing genes from the RHP pathway in an anaerobic digester (31).

In order to further understand the physiology of DIET between an exoelectrogen and Methanothrix, co-cultures were established between G. metallireducens and Methanothrix thermoacetophila. Previous studies have shown that conductive materials can enhance DIET between exoelectrogens and methanogens (33 - 38), and they are frequently added to bioreactors dominated by Methanothrix species (24). Therefore, to more fully understand the impact that conductive materials can have on Methanothrix physiology, two different conductive materials, granular activated carbon (GAC) and magnetite nanoparticles were added to Mx. thermoacetophila cultures. Transcriptomic studies were also done to identify potential pathways for electron transfer between the electron-donating (G. metallireducens) and electron-accepting (Mx. thermoacetophila) partners. These results provide valuable insights into Methanothrix physiology that can be used to better understand carbon flow in many methanogenic terrestrial ecosystems and to help optimize biomethane production from waste.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Mx. thermoacetophila can accept electrons from G. metallireducens via DIET

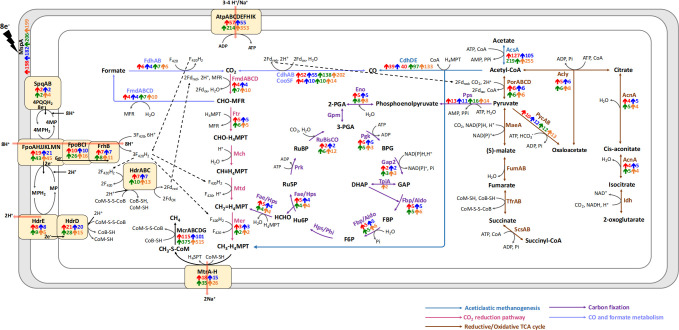

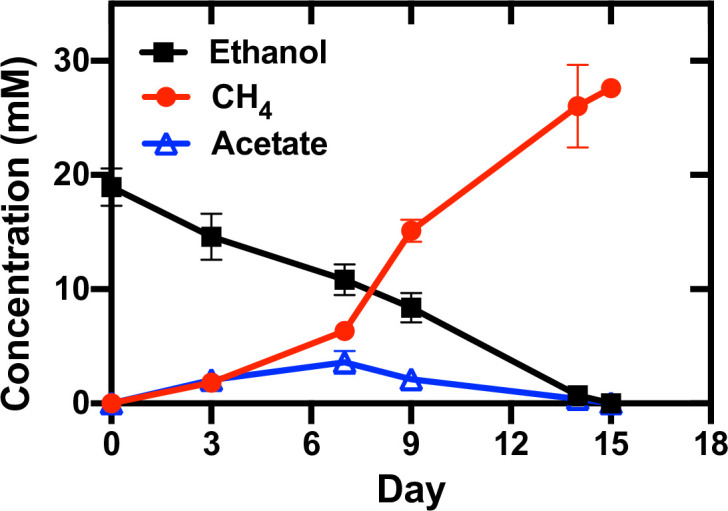

Co-cultures of G. metallireducens and Mx. thermoacetophila were grown with ethanol (20 mM) provided as the sole electron donor, and CO2 [supplied as a gas mixture of N2/CO2 (80/20 v/v) at atmospheric pressure] as the sole electron acceptor (Fig. 1). Neither of the partners would survive alone in this medium, as the bacterium lacked an electron acceptor, and the methanogen lacked an electron donor. Utilization of H2/formate mediated electron transfer was also not possible because G. metallireducens does not produce H2 or formate during ethanol oxidation (39, 40), and Mx. thermoacetophila cannot use H2 or formate as an electron donor (41). Therefore, any methane produced by this co-culture resulted from DIET between G. metallireducens and Mx. thermoacetophila.

Fig 1.

Growth of Geobacter metallireducens and Methanothrix thermoacetophila co-cultures with ethanol (20 mM) provided as the sole electron donor and CO2 provided as the sole electron acceptor. Data represent means and standard deviations from triplicate cultures.

It took 95 days for initial co-culture aggregates to form, which is comparable to the time needed for co-cultures of G. metallireducens and Methanothrix soehngenii to become established (82 days), but much faster than co-cultures with G. metallireducens and Mx. harundinacea (167 days) (19) (Fig. S1). Once DIET was established, ethanol was converted to methane with a yield of 1.46 mol methane/mol ethanol in 15 days, and acetate concentrations initially increased until day 7 and then started to decline (Fig. 1). According to the stoichiometry of ethanol consumption and methane production (equations 1 - 4), two-thirds of the methane generated by the co-culture was produced by acetoclastic methanogenesis, and one-third was produced via DIET (4, 28, 35, 42).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

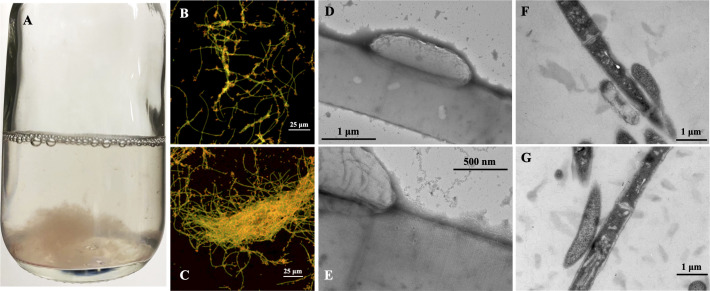

In addition, the rate of methane production was significantly faster than the rate of established co-cultures of G. metallireducens and Mx. harundinacea which took 85 days to reduce 20 mM ethanol to methane (4). This rate was comparable to co-cultures established with G. metallireducens and Methanosarcina vacuolata DH-1 (15 days) but was 1.9–2.3 times faster than rates seen in co-cultures with G. metallireducens and Methanosarcina barkeri (~31 days), Methanosarcina acetivorans (28 days), or Methanosarcina subterranea (35 days) (28, 35, 42). G. metallireducens and Mx. thermoacetophila formed visibly large, loosely clumped aggregates (Fig. 2A), rather than the tight balls formed when G. metallireducens served as the electron-donating partner for DIET with other organisms (4, 40, 43). Confocal (Fig. 2B and C) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 2D through G) images showed that G. metallireducens cells (short orange rods) were closely attached to the sheath of Methanothrix (green long filaments). Quantitative PCR of DNA extracted from these aggregates revealed that G. metallireducens accounted for over three quarters (76.03 ± 2.18%) of the cells, likely because one long fiber-like cell of Methanothrix served as a scaffold for the attachment of multiple Geobacter cells.

Fig 2.

Morphology of Geobacter metallireducens and Methanothrix thermoacetophila co-culture aggregates. (A) Appearance of loose aggregates visible to the naked eye; (B and C) FISH images showing the close attachment of G. metallireducens (short rod, orange) cells to Mx. thermoacetophila (long filament, green); (D and E) Negative-stain TEM images of co-cultures; (F and G) Ultrathin TEM images of co-cultures. FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; TEM, transmission electron microscopy.

Magnetite enhanced growth of Mx. thermoacetophila, while GAC had an inhibitory effect

Previous studies have shown that the addition of conductive materials, such as GAC (19, 38, 44) and magnetite (45), can stimulate DIET between G. metallireducens and an electron-accepting partner. GAC is a representative carbon-based material with a large surface area and high electrical conductivity. In contrast, nanoscale magnetite is a typical iron-based conductive material that is abundant in soils and sediments (46, 47). Therefore, co-cultures were grown in the presence of both of these materials.

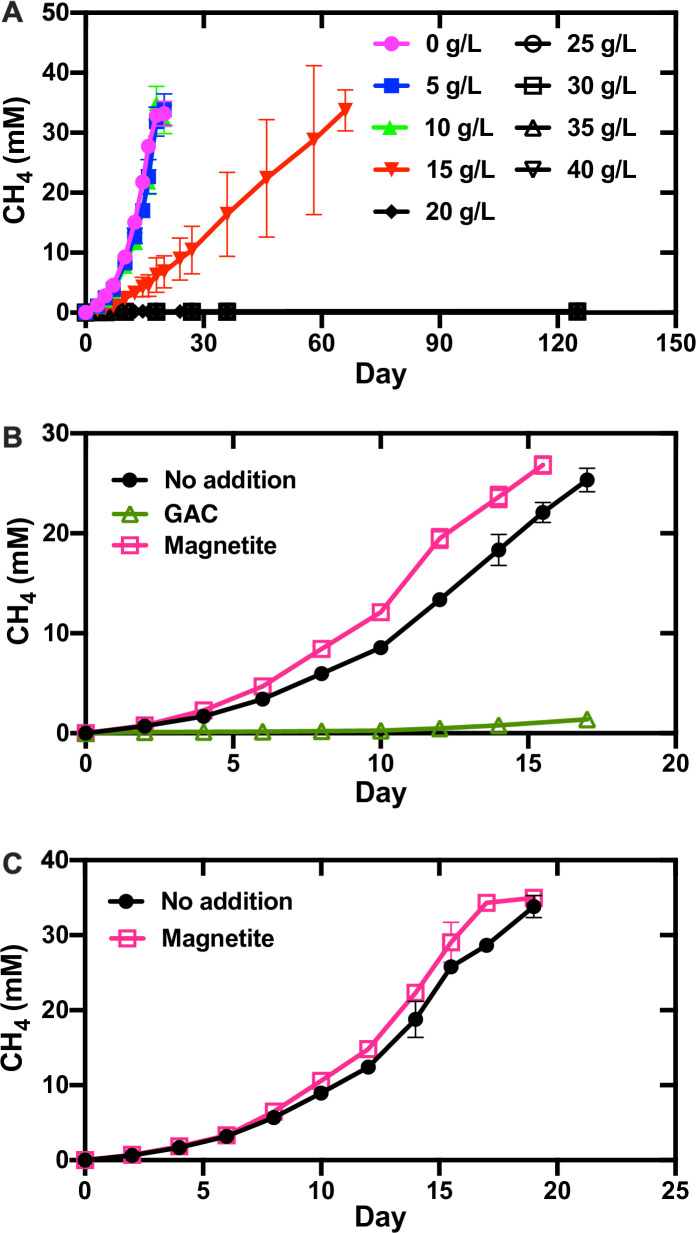

It was surprising to find that growth of Mx. thermoacetophila alone or in co-culture with G. metallireducens was severely impaired by the presence of GAC (Fig. 3). In fact, acetoclastic methanogenesis was inhibited by GAC at concentrations above 20 g/L (Fig. 3A). In addition, DIET co-cultures could not become established in the presence of GAC (Fig. 3B; Fig. S1).

Fig 3.

Effects of granular activated carbon (GAC) and magnetite on methane production by Methanothrix thermoacetophila. (A) Pure cultures using acetate (40 mM) as substrate in the presence of various GAC concentrations; (B) co-cultures using ethanol (20 mM) as substrate in the presence of GAC (40 g/L) or magnetite (10 mM); (C) pure cultures using acetate (40 mM) as substrate in the presence of magnetite (10 mM). Data represent the average and standard deviations from triplicate cultures.

GAC is frequently added to anaerobic digesters to promote methane production (48, 49), and in many cases, the proportion of Methanothrix species declines while Methanosarcina species are enriched in GAC-amended reactors (50 - 53). The results from this study help explain why Methanothrix is often less abundant in GAC-amended reactors and indicate that GAC may not be the best option for stimulation of methanogenesis in environments where Methanothrix is an important member of the community. Further investigations into the inhibitory nature of GAC on the growth of Methanothrix are warranted.

Similar to previous studies with Methanosarcina (54, 55), the addition of magnetite slightly stimulated (1.2 times faster; P value = 0.05) the rate of growth for pure cultures grown by acetoclastic methanogenesis (Fig. 3C). Growth in co-culture was also enhanced and aggregates only took 45 days to form compared to 95 days in nonamended co-cultures (Fig. S1). Once aggregates became established, they grew at rates that were 1.2 times faster (P value = 0.007) (Fig. 3B). Consistent with these results, magnetite additions have also been shown to stimulate methanogenesis by Methanothrix species participating in DIET in anaerobic digesters (56) and by Methanosarcina growing with Geobacter in methanogenic rice paddy soil enrichments (57).

The G. metallireducens DIET transcriptome

G. metallireducens transcriptomes are similar when cells are grown in co-culture with Mx. thermoacetophila or M. barkeri

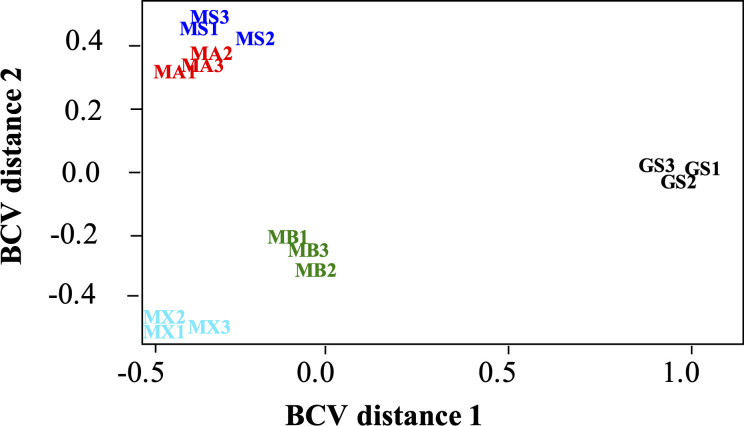

The G. metallireducens transcriptome during growth by DIET with Mx. thermoacetophila (MX) was compared to its DIET transcriptome when grown with other electron-accepting partners [M. barkeri (MB), M. acetivorans (MA), M. subterranea (MS), and Geobacter sulfurreducens (GS)] (58). Multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis plots generated with the biological coefficient of variation (BCV) method (Fig. 4) revealed that the transcriptome of G. metallireducens grown in co-culture with Mx. thermoacetophila was most similar to its transcriptome when it was grown in co-culture with the type I Methanosarcina species, M. barkeri (42). Similar to M. barkeri, Mx. thermoacetophila lacks outer surface c-type cytochromes and does not have any potentially conductive archaella (28, 42). Transcriptomes from G. metallireducens cells grown by DIET with electron-accepting partners with cytochromes and potentially conductive e-pili/archaella (G. sulfurreducens and the type II Methanosarcina species M. acetivorans and M. subterranea) were significantly different.

Fig 4.

Comparison of Geobacter metallireducens RNAseq libraries from co-cultures with Methanothrix thermoacetophila (MX), Methanosarcina barkeri (MB), Methanosarcina acetivorans (MA), Methanosarcina subterranea (MS), and Geobacter sulfurreducens (GS) using multidimensional scaling analysis with the biological coefficient of variation (BCV) method.

Genes from the PccF porin-cytochrome complex were more highly expressed in DIET-grown cells

Electron transport across the outer membrane of Geobacter cells to extracellular electron acceptors such as insoluble Fe(III) oxides or other microorganisms requires porin-c-type-cytochrome (Pcc) complexes (59, 60). G. metallireducens has three Pcc complexes; PccF (Gmet_0908-0910), PccG (Gmet_0911-0913), and PccH (Gmet_0825-0827) (58, 61). Similar to previous studies of DIET with G. metallireducens serving as the electron-donating partner (58), genes from the PccH complex were not highly expressed by G. metallireducens cells grown in co-culture with Mx. thermoacetophila. However, the number of transcripts from PccF complex genes, omcF (Gmet_0910), omaF (Gmet_0909), and ombF (Gmet_0908) were 6.0 (P value = 1.4 × 10−11), 5.3 (P value = 7.2 × 10−12), and 5.9 (P value = 4.1 × 10−11) times more abundant in DIET-grown cells than Fe(III) respiring cells (Table 1; Table S1). Levels of transcripts from PccG complex genes, omcG (Gmet_0913), omaG (Gmet_0912), and ombG (Gmet_0911) were lower than the median RPKM values (Table S2) indicating that PccG was not important for DIET with Mx. thermoacetophila. Addition of magnetite to the G. metallireducens/Mx. thermoacetophila co-cultures increased the expression of PccG genes (Table 1), but the expression was still well below the median RPKM value (Table S2). This same pattern of increased expression of PccF relative to PccG genes was observed when G. metallireducens was grown in co-culture with M. barkeri (58).

TABLE 1.

Differences in expression of genes coding for electron transfer proteins in Geobacter metallireducens cells grown under various conditionsa

| Locus ID | Annotation | Gene | Location | DIET vs Fe(III)- citrate | DIET- magnetite vs DIET | DIET vs DIET- magnetite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gmet_0910 | 10 heme c-type cytochrome from PccF complex | omcF | Outer membrane/surface | 6.00 | 2.96 | NS |

| Gmet_0909 | 9 heme periplasmic c-type cytochrome from PccF complex | omaF | Periplasmic | 5.32 | 2.76 | NS |

| Gmet_0908 | Porin protein from the PccF complex | ombF | Outer membrane/surface | 5.88 | 2.11 | NS |

| Gmet_0913 | 9 heme outer membrane c-type cytochrome from PccG | omcG | Outer membrane/surface | NS | 2.78 | NS |

| Gmet_0912 | 8 heme periplasmic c-type cytochrome from PccG complex | omaG | Periplasmic | NS | 4.79 | NS |

| Gmet_0911 | Porin protein from the PccG complex | ombG | Outer membrane/surface | NS | 3.64 | NS |

| Gmet_1399 | Type IV major pilin subunit, PilA | pilA | Outer membrane/surface | NS | NS | 2.96 |

| Gmet_1400 | Short pilin chaperone protein, Spc | spc | Outer membrane/surface | NS | NS | 4.29 |

| Gmet_2928 | 7 heme c-type cytochrome protein from CbcABCDE | cbcA | Periplasmic | 28.86 | NS | NS |

| Gmet_2929 | b-type cytochrome from CbcABCDE complex | cbcB | Inner membrane | 41.70 | NS | NS |

| Gmet_2930 | Cytochrome c family protein, 11 hemes | cbcC | Periplasmic | 2.55 | NS | NS |

| Gmet_2931 | Monoheme c-type cytochrome protein from CbcABCDE complex | cbcD | Periplasmic | 2.00 | NS | NS |

| Gmet_2932 | Membrane protein from CbcABCDE complex | cbcE | Inner membrane | 2.80 | 2.35 | NS |

| Gmet_0533 | Membrane protein from CbcMNOPQR | cbcQ | Inner membrane | 51.56 | NS | NS |

| Gmet_0534 | c-type cytochrome protein, 5 hemes | cbcR | Periplasmic | 28.19 | NS | NS |

| Gmet_0930 | c-type cytochrome, 8 hemes | Outer membrane/surface | 20.45 | NS | NS | |

| Gmet_1210 | c-type cytochrome, 2 hemes | ccpB | Periplasmic | 5.95 | NS | NS |

| Gmet_0252 | Monoheme c-type cytochrome protein | coxB | Inner membrane | 4.53 | NS | NS |

| Gmet_1809 | c-type cytochrome, 5 hemes | actA | Inner membrane | 3.98 | NS | NS |

| Gmet_1019 | c-type cytochrome, 2 hemes | narC | Inner membrane | 3.81 | NS | NS |

| Gmet_2626 | Monoheme P460 c-type cytochrome | Unknown | 3.37 | NS | NS | |

| Gmet_0294 | c-type cytochrome, 4 hemes | nrfA | Periplasmic | 3.14 | NS | NS |

| Gmet_3091 | c-type cytochrome protein, 2 hemes | macA | Periplasmic | 3.07 | 2.69 | NS |

| Gmet_0679 | c-type cytochrome, 5 hemes | Unknown | 2.84 | NS | NS | |

| Gmet_1197 | c-type cytochrome, 5 hemes | Unknown | 2.71 | 3.14 | NS | |

| Gmet_0142 | c-type cytochrome, 8 hemes | Periplasmic | 2.44 | NS | NS | |

| Gmet_1814 | Monoheme c-type cytochrome | actE | Unknown | 2.30 | NS | NS |

| Gmet_0292 | Diheme c-type cytochrome | Outer membrane/surface | 2.08 | NS | NS | |

| Gmet_1647 | Diheme c-type cytochrome | Unknown | 2.07 | NS | NS | |

| Gmet_0558 | c-type cytochrome protein, 27 hemes | omcO | Unknown | NS | 10.62 | NS |

| Gmet_1087 | Monoheme c-type cytochrome | Unknown | NS | 7.19 | NS | |

| Gmet_0571 | c-type cytochrome protein, 34 hemes | Outer membrane/surface | NS | 3.23 | NS | |

| Gmet_0121 | Diheme c-type cytochrome | Unknown | NS | 2.89 | NS | |

| Gmet_2896 | c-type cytochrome protein, 4 hemes | Outer membrane/surface | NS | 2.79 | NS | |

| Gmet_0600 | c-type cytochrome protein, 19 hemes | Outer membrane/surface | NS | 2.67 | NS | |

| Gmet_2839 | c-type cytochrome protein, 11 hemes | Periplasmic | NS | 2.65 | NS | |

| Gmet_1094 | Diheme c-type cytochrome | cccA | Unknown | NS | 2.45 | NS |

| Gmet_0330 | Monoheme c-type cytochrome | narH | Inner membrane | NS | 2.36 | NS |

| Gmet_0557 | c-type cytochrome protein, 4 hemes | Unknown | NS | 2.25 | NS | |

| Gmet_0598 | c-type cytochrome protein, 22 hemes | Outer membrane/surface | NS | 2.15 | NS | |

| Gmet_1846 | Diheme c-type cytochrome | ppcE | Periplasmic | NS | NS | 3.06 |

| Gmet_2902 | Diheme c-type cytochrome | ppcA | Periplasmic | NS | NS | 4.08 |

| Gmet_3166 | Diheme c-type cytochrome | ppcB | Periplasmic | NS | NS | 2.75 |

| Gmet_1867 | c-type cytochrome protein, 8 hemes | Unknown | NS | NS | 2.45 | |

| Gmet_2432 | Monoheme P460 c-type cytochrome | Unknown | NS | NS | 5.57 |

Values represent fold differences between G. metallireducens cells grown by DIET with Methanothrix thermoacetophila compared to growth with ethanol (20 mM) as the electron donor and ferric citrate (56 mM) as the electron acceptor (DIET vs Fe(III)-citrate); G. metallireducens cells grown by DIET with Mx. thermoacetophila in the presence of 10 mM magnetite versus DIET without magnetite (DIET-magnetite vs DIET); or G. metallireducens cells grown by DIET with Mx. thermoacetophila without magnetite compared to DIET with magnetite (DIET vs DIET-magnetite). Only genes with fold differences >2 and P values <0.05 were considered significant. NS: no significant difference. P values are available in Table S1.

Pilin genes were not more highly expressed in DIET-grown cells

Although genes coding for PilA, the monomer of Geobacter e-pili (62), and Spc, the putative e-pili chaperone protein (63), were being expressed by DIET-grown cells at levels >3.5 times above the median RPKM values (Table S2), significant differences in expression were not observed between DIET- and Fe(III)-respiring cells (Table 1). These results suggest that e-pili may not be as important for DIET with Mx. thermoacetophila as they are for DIET with M. acetivorans and G. sulfurreducens, both of which required e-pili for DIET-based growth and expressed pilA and spc genes at levels that were >two fold higher in DIET-grown cells than Fe(III)-respiring cells (28, 39). Other electron-accepting species lacking c-type cytochromes, M. barkeri and Methanobacterium electrotrophus do not require e-pili for DIET (37, 58, 64). Therefore, Mx. thermoacetophila may be another electron-accepting partner lacking outer surface c-type cytochromes that does not require e-pili for participation in DIET. However, further studies with gene deletion strains are required.

It was also interesting to find that the addition of magnetite to the co-cultures decreased the expression of e-pili associated genes; pilA (Gmet_1399) and spc (Gmet_1400) transcripts were 3.0 (P value = 2.3 × 10−9) and 4.3 (P value = 8.6 × 10−11) times less abundant in DIET co-cultures amended with magnetite (Table 1; Table S1). Studies have indicated that magnetite can compensate for pilin-associated c-type cytochromes involved in extracellular electron exchange during DIET between Geobacter species (45, 65).

Genes coding for Gmet_0930 and the CbcABCDE complex were highly expressed by DIET-grown cells

Genes coding for two periplasmic multiheme c-type cytochromes (Gmet_2928 and Gmet_0534) and an outer surface multiheme c-type cytochrome (Gmet_0930) were >20 times more highly expressed by G. metallireducens cells grown by DIET with Mx. thermoacetophila than Fe(III)-respiring cells (Table 1). Gmet_2928 codes for CbcA, a periplasmic 7-heme cytochrome that is part of the cytochrome bc complex CbcABCDE (Gmet_2928-2932). Cytochrome bc (Cbc) complexes are composed of a transmembrane b-type cytochrome in close association with at least one multiheme c-type cytochrome, and they are involved in shuttling electrons from the quinone pool in the inner membrane to c-type cytochromes found in the periplasmic space (60, 66, 67). The gene coding for CbcA and other components of this complex, the b-type cytochrome (CbcB), two other periplasmic c-type cytochromes (CbcC and CbcD), and a membrane protein (CbcE), were 28.9 (P value = 2.0 × 10−14), 41.7 (P value = 5.7 × 10−14), 2.6 (P value = 2.2 × 10−6), 2.0 (P value = 2.1 × 10−6), and 2.8 (P value = 1.5 × 10−8) times more highly expressed in DIET-grown cells than Fe(III)-respiring cells (Table 1; Table S1).

Gmet_0534 codes for a 5-heme periplasmic cytochrome putatively associated with another Cbc complex, CbcMNOPQR (Gmet_0533–0539). Although this gene was 28.2 times (P value = 3.5 × 10−14) more highly expressed in DIET-grown cells, cbcQ was the only other gene from this complex that was more highly expressed by DIET-grown cells (Table 1; Table S1). Genes from both the CbcABCDE and CbcMNOPQR complexes were highly expressed by G. metallireducens cells grown by DIET with other electron-accepting partners and during growth with insoluble Fe(III) oxide; however, genetic studies showed that they were not required for growth in either of these conditions (58, 68).

Gmet_0930 encodes an 8-heme outer surface c-type cytochrome that was 20.4 (P value = 7.5 × 10−14) times more highly expressed by DIET-grown than Fe(III)-respiring cells (Table 1; Table S1). G. metallireducens requires this c-type cytochrome for formation of DIET aggregates with G. sulfurreducens (58) and it was among the most highly expressed genes by G. metallireducens cells grown in co-culture with M. acetivorans, M. subterranea, and M. barkeri. Although Gmet_0930 deletion mutant strains eventually adapted to grow in co-culture with all three Methanosarcina species, growth was impaired even after four transfers indicating that Gmet_0930 was also important for DIET with these other partners (58).

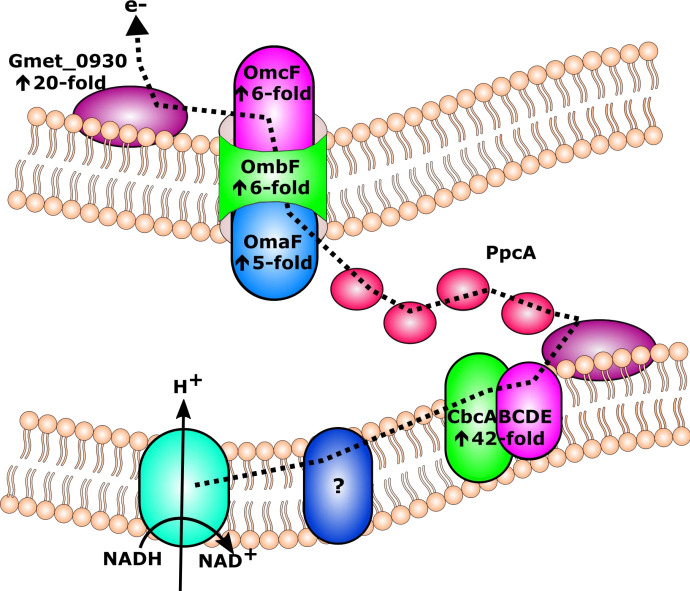

Significant differences in expression of the periplasmic cytochrome PpcA (Gmet_2902) were not observed between DIET grown and Fe(III)-respiring cells. However, PpcA (Gmet_2902) was the second most highly expressed c-type cytochrome with values that were 21 times higher (P values = 3.2 × 10−5) than median RPKM values for both DIET and DIET-magnetite conditions (Table S2). PpcA is highly conserved among Geobacter species and it is required for optimal Fe(III) reduction by G. sulfurreducens (69, 70). Based on analysis of transcriptomic data, it is proposed that the route for electron transfer from the quinone pool in the G. metallireducens inner membrane to Mx. thermoacetophila during DIET requires activity from the CbcABCDE complex, periplasmic PpcA, the PccF conduit (omaF, ombF, and omcF), and the outer surface c-type cytochrome Gmet_0930 (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

Proposed pathway for electron transfer in Geobacter metallireducens during DIET with Methanothrix thermoacetophila. Electrons are transferred from the quinone pool in the inner membrane to the CbcABCDE quinone-oxidoreductase complex, then to the periplasmic c-type cytochrome PpcA, which then shuttles electrons to the PccF (OmaF, OmbF, and OmcF) porin-cytochrome complex and then to the outer surface octaheme cytochrome encoded by Gmet_0930. Electrons may then be transferred directly to Mx. thermoacetophila. Arrows represent fold upregulated in DIET grown cells compared to cells grown with ethanol as the electron donor and ferric citrate as the electron acceptor (for proteins composed of multiple subunits, values from the most highly expressed subunits are shown). If an arrow is not listed with a protein from the proposed pathway, the gene was not differentially expressed between DIET- and Fe(III)-respiring cells. DIET, direct interspecies electron transfer.

The Mx. thermoacetophila DIET transcriptome

Unfortunately, analysis of transcriptomic data did not reveal any significant differences between DIET-based and acetoclastic metabolism in Mx. thermoacetophila. In all of the conditions, most genes from pathways for methanogenesis from acetate and CO2, carbon fixation, the reductive citric acid cycle, and carbon monoxide and formate metabolism had RPKM values that were more than two-fold above median RPKM values (Supplementary text; Fig. 6; Table S3). Many of these genes were also more highly expressed under both acetoclastic and DIET-based conditions in the presence of magnetite.

Fig 6.

Proposed pathways used by Methanothrix thermoacetophila during growth by acetoclastic and DIET-based methanogenesis in the presence or absence of magnetite. Arrows represent fold increase from median RPKM values (P values < 0.05) under DIET (red), acetate (blue), DIET+magnetite (green), and acetate+magnetite (orange) conditions. If proteins are composed of multiple subunits, values from the most highly expressed subunit are represented. Details regarding the fold differences and P values of each gene are provided in Table S3. CHO-MFR: formylmethanofuran; CHO-H4MPT: formyltetrahydromethanopterin; CH≡H4MPT: methenyltetrahydromethanopterin; CH2=H4MPT: methylenetetrahydromethanopterin; CH3-H4MPT: methyltetrahydromethanopterin; CH3-S-CoM: 2-(methylthio)ethanesulfonate; Acetyl-CoA: acetyl-coenzyme A; 2-PGA: 2-phosphoglycerate; 3-PGA: 3-phosphoglycerate; BPG: 1,3-diphosphoglycerate; GAP: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; DHAP: dihydroxyacetone phosphate; FBP: fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; F6P: fructose 6-phosphate; Hu6P: D-arabino-3-hexulose-6-phosphate; Ru5P: ribulose-5-phosphate; HCHO: formaldehyde; RuBP: ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate; MP/MPH2: oxidized/reduced forms of methanophenazine. DIET, direct interspecies electron transfer.

More specifically, comparison of DIET- to acetate-grown cells revealed that genes from the CO2 reduction and the RHP carbon fixation pathways were being highly expressed by cells in both conditions. Previous studies have suggested that these genes are only highly expressed by DIET-grown Methanothrix cells (2, 4, 25, 31). However, transcriptomic comparisons between DIET-grown and acetoclastic cells were not done in these experiments.

The only clear differences in expression patterns between DIET- and acetate-grown cells were related to genes coding for gas vesicle proteins. Two gas vesicle gene clusters (Mthe_0055-0063 and Mthe_0069-0073) were >2 times (P value <0.05) more highly expressed in acetate-grown cells than DIET-grown cells in the presence and absence of magnetite (Table 2). Gas vesicles are commonly found in archaeal sheaths, including those from Mx. thermoacetophila, and make cells more buoyant within a water column (71, 72). This decrease in expression of gas vesicles during DIET may facilitate better contact between redox proteins on the surface of G. metallireducens and Mx. thermoacetophila.

TABLE 2.

Differences in expression of genes coding for gas vesicle proteins in Methanothrix thermoacetophila cells grown under various conditionsa

| Locus ID | Annotation | Gene | Acetate vs DIET | Acetate-magnetite vs DIET-magnetite | DIET vs DIET-magnetite | Acetate vs acetate-magnetite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mthe_0055 | Gas vesicle synthesis GvpLGvpF fusion | gvpLF | 2.19 | 1.72 | 2.62 | 3.34 |

| Mthe_0056 | Gas vesicle protein GvpO | gvpO | 2.19 | 1.79 | 1.96 | 2.46 |

| Mthe_0058 | Gas vesicle protein GvpN | gvpN | 2.27 | 2.05 | 1.71 | 1.88 |

| Mthe_0060 | Gas vesicle synthesis protein GvpA | gvpA | 2.68 | 2.17 | 3.96 | 5.48 |

| Mthe_0061 | Gas vesicle synthesis protein GvpA | gvpA | 2.63 | 2.17 | 4.12 | 5.02 |

| Mthe_0062 | Gas vesicle synthesis protein GvpA | gvpA | 2.63 | 2.17 | 4.12 | 5.02 |

| Mthe_0063 | Gas vesicle synthesis protein GvpA | gvpA | 2.63 | 2.17 | 4.12 | 5.02 |

| Mthe_0069 | Gas vesicle protein GvpG | gvpG | 2.94 | NS | 4.53 | 11.07 |

| Mthe_0070 | Gas vesicle protein GvpA | gvpA | 2.89 | NS | 1.94 | 6.25 |

| Mthe_0071 | Gas vesicle protein GvpA | gvpM | 2.63 | NS | 2.82 | 8.85 |

| Mthe_0072 | Gas vesicle protein GvpK | gvpK | 2.69 | NS | 2.40 | 5.71 |

| Mthe_0073 | Gas vesicle synthesis GvpLGvpF fusion | gvpLF | 2.47 | NS | 2.06 | 4.72 |

Values represent fold differences between Mx. thermoacetophila cells grown by acetoclastic methanogenesis versus cells grown by DIET with Geobacter metallireducens (acetate vs DIET) as well as in the presence of 10 mM magnetite (acetate-magnetite vs DIET magnetite); Mx. thermoacetophila cells grown by DIET with G. metallireducens without magnetite compared to DIET with magnetite (DIET vs DIET-magnetite); Mx. thermoacetophila cells grown by acetoclastic methanogenesis compared to acetoclastic methanogenesis with magnetite (acetate vs. acetate-magnetite). NS, no significant difference. All P values <0.05 and are available in Table S4. DIET, direct interspecies electron transfer.

Expression of gvp genes was also lower in DIET- and acetate-cells grown in the presence of magnetite. When the medium was supplemented with 10 mM magnetite, Mx. thermoacetophila sheaths were coated with magnetite particles (Fig. S2). It is possible that cells do not need to produce as many gas vesicles in the presence of magnetite for several reasons: (i) magnetite can act as an electron conductor during DIET, (ii) the magnetite particles can serve as a scaffold for biofilm formation during DIET or acetoclastic growth, and (iii) acetate can adsorb to the positively charged magnetite particles reducing the need for cells to maintain buoyancy in the medium. Although transcriptomic data suggest that reduced expression of Gvp proteins is advantageous for DIET or growth in the presence of magnetite, differences in gas vesicle abundance were not obvious in negative-stain and ultrathin TEM images (data not shown).

Possible routes for electron uptake by Mx. thermoacetophila

As discussed above, there were clear differences in expression of many genes in the presence or absence of magnetite (Table S4). However, these differences were not apparent in genes coding for surface-associated proteins that could potentially facilitate direct electron uptake from G. metallireducens (Table 3). This suggests that these genes may not be differentially regulated when cells are grown under varying conditions. Analysis of the most highly expressed surface proteins led us to the following proposed routes for electron uptake into Mx. thermoacetophila. However, this analysis is still speculative.

TABLE 3.

Fold differences from median RPKM values for Methanothrix thermoacetophila genes coding for surface proteins that could potentially facilitate electron uptake from Geobacter metallireducens in all four conditionsa

| Locus ID | Annotation | Gene | DIET | Acetate | DIET-magnetite | Acetate-magnetite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mthe_0878 | Surface pyrroquinoline quinone (PQQ) protein | sqpA | 2.18 | 2.18 | 2.27 | 3.55 |

| Mthe_0322 | Cell surface protein with copper binding domain | 3.97 | 4.48 | 4.73 | 3.54 | |

| Mthe_0787 | Cell surface protein with copper binding domain | 5.42 | 4.55 | 4.50 | 5.08 | |

| Mthe_1273 | Cell surface protein with copper binding domain | 2.95 | 3.27 | 3.33 | 3.78 | |

| Mthe_1510 | Cell surface protein with copper binding domain | 1.67 | 2.42 | 2.21 | 4.12 | |

| Mthe_0046 | Cell surface protein with copper binding domain | 4.06 | 4.21 | 3.33 | 4.70 | |

| Mthe_1626 | Cell surface protein with copper binding domain | 4.32 | 5.44 | 5.81 | 11.72 | |

| Mthe_1069 | Major sheath protein | mspA | 198.15 | 181.98 | 205.78 | 198.57 |

| Mthe_1070 | Major sheath protein | 13.66 | 15.11 | 22.23 | 30.17 | |

| Mthe_0677 | S-layer-related duplication domain | 303.63 | 319.81 | 316.80 | 392.27 | |

| Mthe_0149 | S-layer-related duplication domain | 17.52 | 18.48 | 20.41 | 30.20 | |

| Mthe_1177 | S-layer-related duplication domain | 4.13 | 4.35 | 4.67 | 5.06 |

DIET: Mx. thermoacetophila cells grown in co-culture with G. metallireducens with ethanol (20 mM) as the electron donor (median log2 RPKM value was 7.31), Acetate: Mx. thermoacetophila grown with acetate (40 mM) (median log2 RPKM value was 7.30), DIET-magnetite: DIET with Mx. thermoacetophila and G. metallireducens with ethanol (20 mM) as the electron donor in the presence of magnetite (10 mM) (median log2 RPKM value was 7.29), Acetate-magnetite: Mx. thermoacetophila grown with acetate (40 mM) in the presence of magnetite (10 mM) (median log2 RPKM value was 7.27). All P values are <0.05 and were calculated by ANOVA using the R statistical package. P values are available in Table S3.

The main sheath fiber protein (MspA; Mthe_1069) was the most highly expressed surface-associated gene in all of the conditions and had >181 times (P values <1.14 × 10−5) higher expression than median RPKM values (Table 3; Fig. 6; Table S3). The MspA sheath protein forms amyloid fibrils with extended beta-sheet structures (71) and numerous aromatic amino acid residues (10.7% of the protein residues; Fig. S3). Previous studies have shown that stacked aromatic amino acids in amyloid fibrils confer conductivity (73), suggesting that MspA could be conductive. Thus, the surface-associated MspA sheath fiber protein of Mx. thermoacetophila may facilitate direct electron uptake from G. metallireducens.

Unlike Geobacter or type II Methanosarcina species (42, 60, 74, 75), Mx. thermoacetophila does not have any surface multiheme c-type cytochromes that could readily accept electrons from an extracellular electron donor (1, 76). However, the genome does have a gene coding for a transmembrane pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) binding protein; surface quinoprotein A (sqpA; Mthe_0878) that was highly expressed (Table 3). The PQQ binding site of quinoproteins has a beta-propeller fold composed of antiparallel β-sheets radially arranged around a central tunnel (77, 78). The mature SqpA protein has an extremely high concentration of aromatic amino acids (11.3%) (Fig. S3), and pi stacking of aromatic residues arranged in the center of the funnel-shaped propeller could enhance electron transfer properties of this redox protein. Evidence that surface quinoproteins could be involved in DIET comes from observations that M. barkeri was expressing genes encoding surface quinoproteins during growth via DIET with G. metallireducens (27) and Rhodopseudomonas palustris (29).

It is possible that electrons accepted by a membrane-associated electron carrier such as SqpA are being funneled to Fpo dehydrogenase to reduce F420 or ferredoxin in a manner similar to that suggested by Methanosarcina (Fig. 6) (27 - 29). Unlike mspA and sqpA, Fpo dehydrogenase genes were differentially expressed in cells grown in the presence of magnetite (Table S4). In addition, elucidation of the role that Fpo dehydrogenase might play in DIET is further complicated by the fact that it is also likely to be involved in acetoclastic methanogenesis (21). The Fpo dehydrogenase complex of Mx. thermoacetophila lacks FpoF, which is the subunit that accepts electrons from F420H2 in Methanosarcina species (23, 79). Rather, it has been proposed that iron clusters in the FpoB or FpoI subunits can accept electrons from reduced ferredoxin during acetoclastic growth, and heterodisulfide reduction was observed when Mx. thermoacetophila membranes were incubated with reduced ferredoxin from Methanosarcina mazei (21).

Another possibility is that a soluble iron-sulfur flavoprotein from the same family as FpoF (80, 81) interacts with the Fpo dehydrogenase complex to reduce F420. The Mx. thermoacetophila genome has two genes (Mthe_0174 and Mthe_0959) from the FpoF family that code for proteins that are most similar to the beta subunit from the F420 hydrogenase complex, FrhB. These proteins are not likely to be part of a hydrogenase complex, as the genome lacks genes that code for the other two subunits from this complex (FrhA and FrhG) (82), and hydrogenase activity has not been detected in Mx. thermoacetophila cells (21). One of these FrhB genes (Mthe_0174) was expressed at levels that were >6.6 times (P values <2.6 × 10−6) higher than the median RPKM values in all conditions (Table S3).

Reduced ferredoxin and/or F420H2 generated by Fpo dehydrogenase could then transfer electrons to either the soluble heterodisulfide reductase complex, HdrABC, or the membrane-bound heterodisulfide complex, HdrDE, to reduce CoM-S-S-CoB (Fig. 6). Levels of transcripts for hdrA (Mthe_1576) and hdrDE (Mthe_0980-0981) were >7.4 times (P values <1.1 × 10−6) and >5.0 times (P values <2.7 × 10−5) higher than the median RPKM values for all conditions (Table S3).

Conclusions

G. metallireducens and Mx. thermoacetophila were able to grow syntrophically by coupling the oxidation of ethanol with the reduction of CO2 to methane. Addition of the conductive material magnetite enhanced methanogenesis by acetate dismutation and by DIET, while GAC amendments impaired growth. Transcriptomic studies revealed that G. metallireducens uses mechanisms for electron transport to Mx. thermoacetophila that are similar to those used for electron transport to the type I Methanosarcina, M. barkeri. Both M. barkeri and Mx. thermoacetophila lack outer surface multiheme c-type cytochromes and putatively conductive archaella. Transcription of genes coding for gas vesicle proteins was downregulated during DIET or in the presence of magnetite likely because buoyancy within the water column is not required when cells can adhere to a surface. These results provide invaluable insight into Methanothrix physiology. However, further studies are required to fully understand the role of Methanothrix in methanogenic ecosystems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture conditions

Mx. thermoacetophila DSM 6194 was cultured anaerobically (N2/CO2 80/20, v/v) at 55°C in DSMZ 334 medium (https://www.dsmz.de/microorganisms/medium/pdf/DSMZ_Medium334.pdf) with acetate (40 mM) as the substrate. G. metallireducens GS-15 (ATCC 53774) was routinely cultured anaerobically (N2/CO2 80/20, v/v) at 30°C in freshwater medium with ethanol (20 mM) as the electron donor and ferric citrate (56 mM) as the electron acceptor (83).

It was necessary to adapt both G. metallireducens and Mx. thermoacetophila to similar growth conditions before co-culture experiments could be conducted. G. metallireducens was adapted to grow in Methanothrix medium (DSMZ 334), in which acetate and sulfide were omitted, and ethanol (20 mM) and ferric citrate (56 mM) were supplied as the electron donor and the electron acceptor, respectively. The cultivation temperature for G. metallireducens was gradually increased from 30°C to 42°C, while the cultivation temperature for Mx. thermoacetophila was gradually decreased from 55°C to 42°C.

After G. metallireducens and Mx. thermoacetophila were adapted to grow at 42°C, an equal proportion (10%) of the two partners was added to modified DMSZ 334 medium with ethanol (20 mM) as the electron donor and CO2 as the electron acceptor. Sulfide (0.5 mM) and L-cysteine·HCl (1 mM) were added from sterile anoxic stocks. The co-cultures were cultivated anaerobically (N2/CO2 80/20, v/v) at 42°C.

When noted, GAC (Sigma-Aldrich, C2889, 8-20 mesh, various concentrations) or magnetite nanoparticles (10 mM) were added to the medium before autoclaving. The surface areas and resistivity of the GAC used was 600–800 m2/g (dry basis) and 1,375 μΩ-cm (20°C), respectively. Magnetite nanoparticles with diameters of 20–50 nm were prepared as previously described (45).

RNA extraction and transcriptome analyses

Triplicate cultures (co-cultures, pure cultures of Mx. thermoacetophila and pure cultures of G. metallireducens) were harvested during the midlogarithmic phase for transcriptomic analyses. Specifically, cells from co-cultures and pure cultures of Mx. thermoacetophila were collected when methane concentrations reached ~18 mM, and G. metallireducens cells were collected when Fe(II) concentrations were ~35 mM. Pellets from all samples were formed by centrifugation in 50 mL conical tubes at 4000×g for 15 min at 4°C. After centrifugation, the pellets were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction procedures were performed.

Total RNA from sample pellets was extracted as previously described (84). Whole mRNAseq libraries were generated using the NEB Next UltraTM Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). The clustering of index-coded samples was then performed on a cBot Cluster Generation System. After cluster generation, the library was sequenced on an Illumina Novaseq6000 platform and 150 bp paired-end reads were generated (Magigene Biotechnology, Guangzhou, China).

Raw data were checked with FASTQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/), trimmed with Trimmomatic (85), and merged with FLASH (86). Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) reads were then removed from the libraries with SortMeRNA (87). The trimmed mRNA reads were mapped against genomes of G. metallireducens (CP000148) and Mx. thermoacetophila (CP000477) using SeqMan NGen (DNAStar). Reads were then normalized and processed for differential expression studies using the edgeR package in Bioconductor (88). All genes that were ≥1.5-fold differentially expressed with P values of ≤0.05 are reported in Supplementary Tables.

DNA extraction and quantitative PCR

Genomic DNA was extracted from triplicate co-cultures with the MasterPure complete DNA purification kit (Lucigen). The proportion of G. metallireducens and Mx. thermoacetophila cells in co-cultures was determined with quantitative PCR using the following primer pairs: (i) Gm-f (5′-ATGGCCCACATCTTCATCTC-3′) and Gm-r (5′-TGCATGTTTTCATCCACGAT-3′) which amplified a 104-bp fragment from the bamY gene (Gmet_2143) encoding benzoate-CoA ligase of G. metallireducens (89), and (ii) Mx-f (5′-GAGGATCTTGCCCGGATATT-3′) and Mx-r (5′-TATTGTAACGCCAGAGCCTC-3′) which amplified a 102-bp fragment from the sseA gene (Mthe_1071) encoding the rhodanese domain protein of Mx. thermoacetophila. Quantitative PCR was performed with iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on a QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems).

Microscopy

Microbial cells were routinely checked with phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy (Nikon E600) to ensure that cultures were not contaminated. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) of cell aggregates was conducted as previously described with a few modifications (90). Briefly, co-culture cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% glutaraldehyde in 50 mM PIPES (pH 7.2) at 4°C for 2 h, followed by dehydration in 70% ethanol for 30 min. Cells were then transferred to glass slides, air dried, and immersed in hybridization buffer (900 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, 10% formamide, 0.01% SDS, 5 ng/µL each of the probes, pH 7.2) at 46°C for 2 h. Next, the slides were washed in washing buffer (450 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.01% SDS, pH 7.2) at 48°C for 30 min, rinsed gently with Milli-Q water and examined with a laser scanning confocal microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti2). Probes used in this study were MX825 (5′-[cy5]-TCGCACCGTGGCCGACACCTAGC) for Mx. thermoacetophila and Geo1 (5′-[cy3]-AGAATCCAAGGACTCCGT) for G. metallireducens (4, 40, 91).

For negative-stained TEM, cells of Mx. thermoacetophila from either pure cultures or co-cultures were deposited on carbon-coated copper grids (200-mesh) for 10 min and stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid for 1 min. The grids were then air-dried and examined with a transmission electron microscope (ITACHI-HT7700) at 80 kV. For ultrathin TEM, the aggregates of co-cultures and pure cultures of Mx. thermoacetophila were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) at 4°C overnight and embedded in low-melt agarose (1.5% in phosphate buffer). The agarose-embedded aggregates were then fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 3 h, dehydrated in gradient ethanol solution (30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, 95%, and 100% two times), embedded in Spi-pon 812 resin, polymerized, sectioned, stained with lead citrate and examined with a transmission electron microscope (HITACHI-HT7800) at 80 kV.

For scanning electron microscopy, cells of Mx. thermoacetophila collected during the midlogarithmic phase were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) at 4°C overnight. Cells were then washed with phosphate buffer three times and post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 1 h. Fixed cells were dehydrated at 4°C with gradient ethanol solution (30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, and 100% two times) for 20 min for each step. Cells were then treated with ethanol/isoamyl acetate (v/v=1:1) for 30 min, and pure isoamyl acetate overnight. After dehydration, the samples were dried with a critical point dryer, coated with gold, and observed under a scanning electron microscope (HITACHI-SU8010) at 3 kV.

Analytical techniques

Ethanol concentrations were measured with a gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector (Clarus 600; PerkinElmer Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Acetate concentrations were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (SHIMADZU, Japan) with an Aminex HPX-87H Ion Exclusion column (300 mm × 7.8 mm) and an eluent of 8.0 mM sulfuric acid. Methane was monitored by gas chromatography with a flame ionization detector (SHIMADZU, GC-8A) (92). Ferrous iron concentrations were determined by first incubating cultures in 0.5 N HCl and then measuring Fe(II) concentrations with a ferrozine assay at an absorbance of 562 nm as previously described (93).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Instrument Analysis Center of Shenzhen University for the assistance with the collection of transmission electron microscopy images.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42207144, 92251306, 32225003, and 31970105), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021TQ0212), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20200109105010363), and the Innovation Team Project of Universities in Guangdong Province (2020KCXTD023).

The authors do not declare any conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Meng Li, Email: limeng848@szu.edu.cn.

Terry C. Hazen, University of Tennessee at Knoxville, Knoxville, Tennessee, USA

DATA AVAILABILITY

Illumina sequence reads have been submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) of the NCBI database under BioProject PRJNA914893 and Biosamples SAMN32360990, SAMN32360991, SAMN32360992, SAMN32360993, and SAMN32360994.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.00360-23.

Figures S1 to S3.

Genes that were differentially expressed by G. metallireducens grown under various conditions.

Fold differences from median RPKM values for electron transport genes from G. metallireducens cells grown under various conditions.

Fold difference from median RPKM values for Mx. thermoacetophila genes coding for surface proteins or proteins involved in carbon metabolism under various conditions.

Genes that were differentially expressed by Mx. thermoacetophila grown under various conditions.

Carbon metabolism of Mx. thermoacetophila grown under various conditions.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Smith KS, Ingram-Smith C. 2007. Methanosaeta, the forgotten methanogen? Trends Microbiol 15:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Holmes DE, Shrestha PM, Walker DJF, Dang Y, Nevin KP, Woodard TL, Lovley DR. 2017. Metatranscriptomic evidence for direct interspecies electron transfer between Geobacter and Methanothrix species in methanogenic rice paddy soils. Appl Environ Microbiol 83:e00223-17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00223-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Großkopf R, Janssen PH, Liesack W. 1998. Diversity and structure of the methanogenic community in anoxic rice paddy soil microcosms as examined by cultivation and direct 16S rRNA gene sequence retrieval. Appl Environ Microbiol 64:960–969. doi: 10.1128/AEM.64.3.960-969.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rotaru A-E, Shrestha PM, Liu F, Shrestha M, Shrestha D, Embree M, Zengler K, Wardman C, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. 2014. A new model for electron flow during anaerobic digestion: direct interspecies electron transfer to Methanosaeta for the reduction of carbon dioxide to methane. Energy Environ Sci 7:408–415. doi: 10.1039/C3EE42189A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Angle JC, Morin TH, Solden LM, Narrowe AB, Smith GJ, Borton MA, Rey-Sanchez C, Daly RA, Mirfenderesgi G, Hoyt DW, Riley WJ, Miller CS, Bohrer G, Wrighton KC. 2017. Methanogenesis in oxygenated soils is a substantial fraction of wetland methane emissions. Nat Commun 8:1567. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01753-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tang Y, Shigematsu T, Morimura S, Kida K. 2005. Microbial community analysis of mesophilic anaerobic protein degradation process using bovine serum albumin (BSA) -fed continuous cultivation. J Biosci Bioeng 99:150–164. doi: 10.1263/jbb.99.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Díaz EE, Stams AJM, Amils R, Sanz JL. 2006. Phenotypic properties and microbial diversity of methanogenic granules from a full-scale upflow anaerobic sludge bed reactor treating brewery wastewater. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:4942–4949. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02985-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morita M, Malvankar NS, Franks AE, Summers ZM, Giloteaux L, Rotaru AE, Rotaru C, Lovley DR. 2011. Potential for direct interspecies electron transfer in methanogenic wastewater digester aggregates. mBio 2:e00159–11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00159-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carr SA, Schubotz F, Dunbar RB, Mills CT, Dias R, Summons RE, Mandernack KW. 2018. Acetoclastic Methanosaeta are dominant methanogens in organic-rich Antarctic marine sediments. ISME J 12:330–342. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tveit AT, Urich T, Frenzel P, Svenning MM. 2015. Metabolic and trophic interactions modulate methane production by Arctic peat microbiota in response to warming. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E2507–E2516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420797112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Romanowicz KJ, Crump BC, Kling GW. 2021. Rainfall alters permafrost soil redox conditions, but meta-omics show divergent microbial community responses by tundra type in the Arctic. Soil Syst 5:17. doi: 10.3390/soilsystems5010017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dean JF, Middelburg JJ, Röckmann T, Aerts R, Blauw LG, Egger M, Jetten MSM, de Jong AEE, Meisel OH, Rasigraf O, Slomp CP, in’t Zandt MH, Dolman AJ. 2018. Methane feedbacks to the global climate system in a warmer world. Rev Geophys 56:207–250. doi: 10.1002/2017RG000559 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rößger N, Sachs T, Wille C, Boike J, Kutzbach L. 2022. Seasonal increase of methane emissions linked to warming in Siberian tundra. Nat Clim Chang 12:1031–1036. doi: 10.1038/s41558-022-01512-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meredith M, Sommerkorn M, Cassotta S, Derksen C, Ekaykin A, Hollowed A, Kofinas G, Mackintosh A, Melbourne-Thomas J, Muelbert M. 2019. Chapter 3, Polar regions. In IPCC special report on the ocean and Cryosphere in a changing climate. doi: 10.1017/9781009157964 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jetten MSM, Stams AJM, Zehnder AJB. 1992. Methanogenesis from acetate: a comparison of the acetate metabolism in Methanothrix soehngenii and Methanosarcina spp. FEMS Microbiol Rev 88:181–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb04987.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ferry JG. 2010. How to make a living by exhaling methane. Annu Rev Microbiol 64:453–473. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sun H, Angelidaki I, Wu S, Dong R, Zhang Y. 2018. The potential of bioelectrochemical sensor for monitoring of acetate during anaerobic digestion: focusing on novel reactor design. Front Microbiol 9:3357. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pan X, Zhao L, Li C, Angelidaki I, Lv N, Ning J, Cai G, Zhu G. 2021. Deep insights into the network of acetate metabolism in anaerobic digestion: focusing on syntrophic acetate oxidation and homoacetogenesis. Water Res 190:116774. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yee MO, Rotaru AE. 2020. Extracellular electron uptake in Methanosarcinales is independent of multiheme c-type cytochromes. Sci Rep 10:372. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57206-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stams AJM, Teusink B, Sousa DZ. 2019. Ecophysiology of Acetoclastic Methanogens, p 1–14. In Stams AJM, DZ Sousa (ed), Biogenesis of hydrocarbons. Springer International Publishing, Cham. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-53114-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Welte C, Deppenmeier U. 2011. Membrane-bound electron transport in Methanosaeta thermophila. J Bacteriol 193:2868–2870. doi: 10.1128/JB.00162-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Berger S, Welte C, Deppenmeier U. 2012. Acetate activation in Methanosaeta thermophila: characterization of the key enzymes pyrophosphatase and acetyl-CoA synthetase. Archaea 2012:315153. doi: 10.1155/2012/315153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Welte C, Deppenmeier U. 2014. Bioenergetics and anaerobic respiratory chains of aceticlastic methanogens. Biochim Biophys Acta 1837:1130–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huang Y, Cai B, Dong H, Li H, Yuan J, Xu H, Wu H, Xu Z, Sun D, Dang Y, Holmes DE. 2022. Enhancing anaerobic digestion of food waste with granular activated carbon immobilized with riboflavin. Sci Total Environ 851:158172. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu C, Sun D, Zhao Z, Dang Y, Holmes DE. 2019. Methanothrix enhances biogas upgrading in microbial electrolysis cell via direct electron transfer. Bioresour Technol 291:121877. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.121877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu C, Yuan X, Gu Y, Chen H, Sun D, Li P, Li M, Dang Y, Smith JA, Holmes DE. 2020. Enhancement of bioelectrochemical CO2 reduction with a carbon brush electrode via direct electron transfer. ACS Sust Chem Eng 8:11368–11375. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c03623 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holmes DE, Rotaru A-E, Ueki T, Shrestha PM, Ferry JG, Lovley DR. 2018. Electron and proton flux for carbon dioxide reduction in Methanosarcina barkeri during direct interspecies electron transfer. Front Microbiol 9:3109. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holmes DE, Zhou J, Ueki T, Woodard T, Lovley DR. 2021. Mechanisms for electron uptake by Methanosarcina acetivorans during direct interspecies electron transfer. mBio 12:e0234421. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02344-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huang L, Liu X, Zhang Z, Ye J, Rensing C, Zhou S, Nealson KH. 2022. Light-driven carbon dioxide reduction to methane by Methanosarcina barkeri in an electric syntrophic coculture. ISME J 16:370–377. doi: 10.1038/s41396-021-01078-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Conklin A, Stensel HD, Ferguson J. 2006. Growth kinetics and competition between Methanosarcina and Methanosaeta in mesophilic anaerobic digestion. Water Environ Res 78:486–496. doi: 10.2175/106143006x95393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yang P, Tan G-YA, Aslam M, Kim J, Lee P-H. 2019. Metatranscriptomic evidence for classical and RuBisCo-mediated CO2 reduction to methane facilitated by direct interspecies electron transfer in a methanogenic system. Sci Rep 9:4116. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40830-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kono T, Mehrotra S, Endo C, Kizu N, Matusda M, Kimura H, Mizohata E, Inoue T, Hasunuma T, Yokota A, Matsumura H, Ashida H. 2017. A RuBisCO-mediated carbon metabolic pathway in methanogenic archaea. Nat Commun 8:14007. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xiao L, Lichtfouse E, Senthil Kumar P. 2021. Advantage of conductive materials on interspecies electron transfer-independent acetoclastic methanogenesis: a critical review. Fuel 305:121577. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.121577 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhao Z, Li Y, Zhang Y, Lovley DR. 2020. Sparking anaerobic digestion: promoting direct interspecies electron transfer to enhance methane production. iScience 23:101794. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rotaru AE, Shrestha PM, Liu F, Markovaite B, Chen S, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. 2014. Direct interspecies electron transfer between Geobacter metallireducens and Methanosarcina barkeri. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:4599–4605. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00895-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chen S, Rotaru A-E, Liu F, Philips J, Woodard TL, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. 2014. Carbon cloth stimulates direct interspecies electron transfer in syntrophic co-cultures. Bioresour Technol 173:82–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zheng S, Liu F, Wang B, Zhang Y, Lovley DR. 2020. Methanobacterium capable of direct interspecies electron transfer. Environ Sci Technol 54:15347–15354. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c05525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu F, Rotaru A-E, Shrestha PM, Malvankar NS, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. 2012. Promoting direct interspecies electron transfer with activated carbon. Energy Environ. Sci 5:8982. doi: 10.1039/c2ee22459c [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shrestha PM, Rotaru AE, Summers ZM, Shrestha M, Liu F, Lovley DR. 2013. Transcriptomic and genetic analysis of direct interspecies electron transfer. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:2397–2404. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03837-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Summers ZM, Fogarty HE, Leang C, Franks AE, Malvankar NS, Lovley DR. 2010. Direct exchange of electrons within aggregates of an evolved syntrophic coculture of anaerobic bacteria. Science 330:1413–1415. doi: 10.1126/science.1196526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kamagata Y, Mikami E. 1991. Isolation and characterization of a novel thermophilic Methanosaeta strain. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 41:191–196. doi: 10.1099/00207713-41-2-191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhou J, Holmes DE, Tang H-Y, Lovley DR. 2021. Correlation of key physiological properties of Methanosarcina isolates with environment of origin. Appl Environ Microbiol 87:e0073121. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00731-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shrestha PM, Rotaru AE, Aklujkar M, Liu F, Shrestha M, Summers ZM, Malvankar N, Flores DC, Lovley DR. 2013. Syntrophic growth with direct interspecies electron transfer as the primary mechanism for energy exchange. Environ Microbiol Rep 5:904–910. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yee MO, Snoeyenbos-West OL, Thamdrup B, Ottosen LDM, Rotaru AE. 2019. Extracellular electron uptake by two Methanosarcina species. Front Energy Res 7:29. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2019.00029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liu F, Rotaru AE, Shrestha PM, Malvankar NS, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. 2015. Magnetite compensates for the lack of a pilin-associated c-type cytochrome in extracellular electron exchange. Environ Microbiol 17:648–655. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rotaru A-E, Calabrese F, Stryhanyuk H, Musat F, Shrestha PM, Weber HS, Snoeyenbos-West OLO, Hall POJ, Richnow HH, Musat N, Thamdrup B. 2018. Conductive particles enable sntrophic acetate oxidation between Geobacter and Methanosarcina from coastal sediments. mBio 9:e00226-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00226-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Maher BA, Taylor RM. 1988. Formation of ultrafine-grained magnetite in soils. Nature 336:368–370. doi: 10.1038/336368a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Abbas Y, Yun S, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Wang K. 2021. Recent advances in bio-based carbon materials for anaerobic digestion: a review. Renew Sust Energ Rev 135:110378. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2020.110378 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Park JH, Kang HJ, Park KH, Park HD. 2018. Direct interspecies electron transfer via conductive materials: a perspective for anaerobic digestion applications. Bioresour Technol 254:300–311. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.01.095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yu N, Guo B, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Zhou Y, Liu Y. 2021. Self-fluidized GAC-amended UASB reactor for enhanced methane production. Chem Eng J 420:127652. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2020.127652 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Xu S, He C, Luo L, Lü F, He P, Cui L. 2015. Comparing activated carbon of different particle sizes on enhancing methane generation in upflow anaerobic digester. Bioresour Technol 196:606–612. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dang Y, Sun D, Woodard TL, Wang LY, Nevin KP, Holmes DE. 2017. Stimulation of the anaerobic digestion of the dry organic fraction of municipal solid waste (OFMSW) with carbon-based conductive materials. Bioresour Technol 238:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lei Y, Sun D, Dang Y, Feng X, Huo D, Liu C, Zheng K, Holmes DE. 2019. Metagenomic analysis reveals that activated carbon aids anaerobic digestion of raw incineration leachate by promoting direct interspecies electron transfer. Water Res 161:570–580. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.06.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fu L, Zhou T, Wang J, You L, Lu Y, Yu L, Zhou S. 2019. NanoFe3O4 as solid electron shuttles to accelerate acetotrophic methanogenesis by Methanosarcina barkeri. Front Microbiol 10:388. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wang H, Byrne JM, Liu P, Liu J, Dong X, Lu Y. 2020. Redox cycling of Fe (II) and Fe (III) in magnetite accelerates aceticlastic methanogenesis by Methanosarcina mazei. Environ Microbiol Rep 12:97–109. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lei Y, Wei L, Liu T, Xiao Y, Dang Y, Sun D, Holmes DE. 2018. Magnetite enhances anaerobic digestion and methanogenesis of fresh leachate from a municipal solid waste incineration plant. Chem Eng J 348:992–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.05.060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kato S, Hashimoto K, Watanabe K. 2012. Methanogenesis facilitated by electric syntrophy via (semi) conductive iron-oxide minerals. Environ Microbiol 14:1646–1654. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02611.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Holmes DE, Zhou J, Smith JA, Wang C, Liu X, Lovley DR. 2022. Different outer membrane c‐type cytochromes are involved in direct interspecies electron transfer to Geobacter or Methanosarcina species. mLife 1:272–286. doi: 10.1002/mlf2.12037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Shi L, Dong H, Reguera G, Beyenal H, Lu A, Liu J, Yu HQ, Fredrickson JK. 2016. Extracellular electron transfer mechanisms between microorganisms and minerals. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:651–662. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ueki T. 2021. Cytochromes in extracellular electron transfer in Geobacter. Appl Environ Microbiol 87:e03109-20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03109-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Shi L, Fredrickson JK, Zachara JM. 2014. Genomic analyses of bacterial porin-cytochrome gene clusters. Front Microbiol 5:657. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Reguera G, McCarthy KD, Mehta T, Nicoll JS, Tuominen MT, Lovley DR. 2005. Extracellular electron transfer via microbial nanowires. Nature 435:1098–1101. doi: 10.1038/nature03661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Liu X, Zhan J, Jing X, Zhou S, Lovley DR. 2019. A pilin chaperone required for the expression of electrically conductive Geobacter sulfurreducens pili . Environ Microbiol 21:2511–2522. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zheng S, Liu F. 2021. Complete genome sequence of Methanobacterium electrotrophus strain YSL, isolated from coastal riverine sediments. Microbiol Resour Announc 10:e0075221. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00752-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ueki T, Nevin KP, Rotaru A-E, Wang L-Y, Ward JE, Woodard TL, Lovley DR. 2018. Geobacter strains expressing poorly conductive pili reveal constraints on direct interspecies electron transfer mechanisms. mBio 9:e01273-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01273-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Butler JE, Young ND, Lovley DR. 2010. Evolution of electron transfer out of the cell: comparative genomics of six Geobacter genomes. BMC Genomics 11:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zhong Y, Shi L. 2018. Genomic analyses of the quinol oxidases and/or quinone reductases involved in bacterial extracellular electron transfer. Front Microbiol 9:3029. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Smith JA, Lovley DR, Tremblay PL. 2013. Outer cell surface components essential for Fe (III) oxide reduction by Geobacter metallireducens. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:901–907. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02954-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lloyd JR, Leang C, Myerson ALH, Coppi MV, Cuifo S, Methe B, Sandler SJ, Lovley DR. 2003. Biochemical and genetic characterization of PpcA, a periplasmic c-type cytochrome in Geobacter sulfurreducens. Biochem J 369:153–161. doi: 10.1042/bj20020597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Morgado L, Dantas JM, Bruix M, Londer YY, Salgueiro CA. 2012. Fine tuning of redox networks on multiheme cytochromes from Geobacter sulfurreducens drives physiological electron/proton energy transduction. Bioinorg Chem Appl 2012:298739. doi: 10.1155/2012/298739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Dueholm MS, Larsen P, Finster K, Stenvang MR, Christiansen G, Vad BS, Bøggild A, Otzen DE, Nielsen PH. 2015. The tubular sheaths encasing Methanosaeta thermophila filaments are functional amyloids. J Biol Chem 290:20590–20600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.654780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Pfeifer F. 2012. Distribution, formation and regulation of gas vesicles. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:705–715. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Shipps C, Kelly HR, Dahl PJ, Yi SM, Vu D, Boyer D, Glynn C, Sawaya MR, Eisenberg D, Batista VS, Malvankar NS. 2021. Intrinsic electronic conductivity of individual atomically resolved amyloid crystals reveals micrometer-long hole hopping via tyrosines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118:e2014139118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2014139118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lovley DR, Ueki T, Zhang T, Malvankar NS, Shrestha PM, Flanagan KA, Aklujkar M, Butler JE, Giloteaux L, Rotaru A-E, Holmes DE, Franks AE, Orellana R, Risso C, Nevin KP. 2011. Geobacter: the microbe electric’s physiology, ecology, and practical applications, p 1–100. In Poole RK (ed), Advances in microbial physiology. Academic Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lovley DR, Holmes DE. 2022. Electromicrobiology: the ecophysiology of phylogenetically diverse electroactive microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol 20:5–19. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00597-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Barber RD, Zhang L, Harnack M, Olson MV, Kaul R, Ingram-Smith C, Smith KS. 2011. Complete genome sequence of Methanosaeta concilii, a specialist in aceticlastic methanogenesis. J Bacteriol 193:3668–3669. doi: 10.1128/JB.05031-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Pons T, Gómez R, Chinea G, Valencia A. 2003. Beta-propellers: associated functions and their role in human diseases. Curr Med Chem 10:505–524. doi: 10.2174/0929867033368204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kopec KO, Lupas AN. 2013. β-propeller blades as ancestral peptides in protein evolution. PLoS One 8:e77074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Welte C, Deppenmeier U. 2011. Re-evaluation of the function of the F420 dehydrogenase in electron transport of Methanosarcina mazei. FEBS J 278:1277–1287. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08048.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Johnson EF, Mukhopadhyay B. 2005. A new type of sulfite reductase, a novel coenzyme F420-dependent enzyme, from the methanarchaeon Methanocaldococcus jannaschii. J Biol Chem 280:38776–38786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503492200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Mills DJ, Vitt S, Strauss M, Shima S, Vonck J. 2013. De novo modeling of the F420-reducing [Nife]-hydrogenase from a methanogenic archaeon by cryo-electron microscopy. Elife 2:e00218. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kulkarni G, Mand TD, Metcalf WW. 2018. Energy conservation via hydrogen cycling in the methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina barkeri. mBio 9:e01256-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01256-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Lovley DR, Giovannoni SJ, White DC, Champine JE, Phillips EJ, Gorby YA, Goodwin S. 1993. Geobacter metallireducens gen. nov. sp. nov., a microorganism capable of coupling the complete oxidation of organic compounds to the reduction of iron and other metals. Arch Microbiol 159:336–344. doi: 10.1007/BF00290916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Holmes DE, Risso C, Smith JA, Lovley DR. 2012. Genome-scale analysis of anaerobic benzoate and phenol metabolism in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Ferroglobus placidus. ISME J 6:146–157. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Magoč T, Salzberg SL. 2011. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27:2957–2963. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Kopylova E, Noé L, Touzet H. 2012. SortMeRNA: fast and accurate filtering of ribosomal RNAs in metatranscriptomic data. Bioinformatics 28:3211–3217. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. 2010. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Smith JA, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. 2015. Syntrophic growth via quinone-mediated interspecies electron transfer. Front Microbiol 6:121. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Pernthaler J, Glöckner F-O, Schönhuber W, Amann R. 2001. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes. Methods Microbiol 30:207–226. doi: 10.1016/S0580-9517(01)30046-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Raskin L, Stromley JM, Rittmann BE, Stahl DA. 1994. Group-specific 16S rRNA hybridization probes to describe natural communities of methanogens. Appl Environ Microbiol 60:1232–1240. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.4.1232-1240.1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Holmes DE, Giloteaux L, Orellana R, Williams KH, Robbins MJ, Lovley DR. 2014. Methane production from protozoan endosymbionts following stimulation of microbial metabolism within subsurface sediments. Front Microbiol 5:366. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Lovley DR, Phillips EJ. 1986. Organic matter mineralization with reduction of ferric iron in anaerobic sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 51:683–689. doi: 10.1128/aem.51.4.683-689.1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figures S1 to S3.

Genes that were differentially expressed by G. metallireducens grown under various conditions.

Fold differences from median RPKM values for electron transport genes from G. metallireducens cells grown under various conditions.

Fold difference from median RPKM values for Mx. thermoacetophila genes coding for surface proteins or proteins involved in carbon metabolism under various conditions.

Genes that were differentially expressed by Mx. thermoacetophila grown under various conditions.

Carbon metabolism of Mx. thermoacetophila grown under various conditions.

Data Availability Statement

Illumina sequence reads have been submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) of the NCBI database under BioProject PRJNA914893 and Biosamples SAMN32360990, SAMN32360991, SAMN32360992, SAMN32360993, and SAMN32360994.