Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

In 2020, firearm injuries became the leading cause of death among US children and adolescents. This study aimed to evaluate new 2021 data on US pediatric firearm deaths and disparities to understand trends compared with previous years.

METHODS

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research was queried for firearm mortalities in children/adolescents from 2018 to 2021. Absolute mortality, death rates, and characteristics were reported. Death rates were defined per 100 000 persons in that population per year. Death rates across states were illustrated via geographic heat maps, and correlations with state poverty levels were calculated.

RESULTS

In 2021, firearms continued to be the leading cause of death among US children. From 2018 to 2021, there was a 41.6% increase in the firearm death rate. In 2021, among children who died by firearms, 84.8% were male, 49.9% were Black, 82.6% were aged 15 to 19 years, and 64.3% died by homicide. Black children accounted for 67.3% of firearm homicides, with a death rate increase of 1.8 from 2020 to 2021. White children accounted for 78.4% of firearm suicides. From 2020 to 2021, the suicide rate increased among Black and white children, yet decreased among American Indian or Alaskan Native children. Geographically, there were worsening clusters of firearm death rates in Southern states and increasing rates in Midwestern states from 2018 to 2021. Across the United States, higher poverty levels correlated with higher firearm death rates (R = 0.76, P < .001).

CONCLUSIONS

US pediatric firearm deaths increased in 2021, above the spike in 2020, with worsening disparities. Implementation of prevention strategies and policies among communities at highest risk is critical.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Firearm injury became the leading cause of death in children in 2020, and certain populations, males, older adolescents, and Black children have historically been at highest risk.

What This Study Adds:

This study explores the changes in firearm mortality trends and disparities with the most up-to-date data available and demonstrates areas of worsening disparity.

Firearm deaths among US children and adolescents have steadily increased with widening disparities. In 2020, pediatric firearm deaths increased 28.8%, a staggering surge compared with uptrends in years before the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.1,2 As such, firearms became the leading cause of death among children, surpassing motor vehicle accidents for the first time. Spikes in firearm purchasing during the pandemic were substantial, resulting in roughly 30 million children living in households with firearms,3 a known risk factor for pediatric firearm injury.4 In recent years, pediatric firearm deaths from all intents increased, with homicides accounting for the majority, in contrast to adults, where suicide was the main driver.2,5

Disparities across pediatric firearm deaths have been described, particularly with respect to sociodemographic and geographic distribution. The burden of pediatric firearm death has disproportionately affected communities of color.5,6 Black children have significantly higher rates of firearm mortalities overall.2,6 Males account for nearly 80% of firearm deaths, a steady statistic despite continued increases in overall firearm mortality. Many of these disparate trends are largely accounted for by homicides.2,6,7 Geographically, pediatric firearm deaths are not equally distributed, with previous studies demonstrating a greater burden in Southeastern states,2 particularly for pediatric firearm homicides. In contrast, firearm suicides are more geographically dispersed, with higher rates observed in Midwest and Western states, and greater impact among white and American Indian or Alaskan Native (AIAN) children.2 Additional studies demonstrate clustering of homicides in urban areas and suicides in rural areas.2 Furthermore, increased firearm mortality rates are correlated with higher poverty levels and lower socioeconomic status, which may contribute to unequal racial, ethnic, and state distributions.8 Disparate patterns in firearm mortalities have substantial implications, furthering inequities and structural violence in health and economic disadvantage.9

Questions remain as to whether the pandemic surge in pediatric firearm deaths from 2019 to 2020 was because of exceptional circumstances, or whether this represented an alarming new baseline upon which continued increases would be observed.10–13 Data on pediatric firearm deaths and disparities beyond 2020 have not yet been described. By analyzing recent pediatric firearm deaths and associated disparities, this study sought to enhance understanding of the trajectory of this epidemic, identify opportunities for intervention among populations at increased risk, and inform public health solutions that expeditiously address these preventable childhood deaths. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess pediatric and adolescent firearm mortality temporal trends and disparities regarding age, gender, race, ethnicity, geography, and socioeconomic status.

Methods

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) maintains a publicly available data query system called Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER).14 This data set provides access to an array of public health data, including demographics, mortality, underlying causes of death, and intent. Mortality data are obtained from death certificates filed in all 50 states and Washington, District of Columbia.

CDC WONDER was queried for firearm-related mortality data and additional injury mortalities among children and adolescents (aged 0–19) from 2018 to 2021.15 For analysis, 4-year age groups (0–4, 5–9, 10–14, and 15–19) were used for stratification.16 For firearm intent, classification was based on International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, codes (Homicide X92–Y09, Suicide X71–X83, and Unintentional W00–X58), as defined by CDC WONDER.14,17 Undetermined deaths were included in total death counts; however, low absolute death counts prohibited further subanalyses in this intent category. Absolute mortality numbers, crude death rates, and baseline characteristics were reported. Using the definition provided by the CDC, crude death rate is defined as the total number of deaths during a specific year in the population category of interest, divided by the at-risk population × 100 000.14 Within all stratified analyses, death rate refers to the rate of deaths per 100 000 persons within the specified population for the specified year. Changes in death rates were calculated as the difference in death rate between years. Percentage change of death rate was calculated as the difference in death rates over the starting death rate. Subanalyses stratifying firearm injury by intent, age, race, and gender were also performed.

Differences in death rates across the United States from 2018 to 2021 were illustrated via geographic heat maps using the Microsoft application, GeoNames.18 States reporting absolute mortalities of <20 persons were excluded, because numbers below this threshold are considered unreliable by the CDC. Additionally, state death rates were correlated with state poverty levels using the Small Area Income and Poverty Estimate interactive tool from the US Census Bureau.19 In this tool, poverty thresholds were determined on the basis of household income by size of the family unit, and percentage of population living in poverty was determined by a formula incorporating tax, census, and public benefit program data.19 The percentage of population living in poverty by state was plotted against pediatric firearm death rates and Pearson R correlation coefficients were calculated. P values were calculated with a 2-tailed t test, with the level of significance specified as P < .05.

Results

1. Pediatric Firearm Mortality Temporal Trends

Overall, from 2018 to 2021, there was a 41.5% increase in pediatric firearm death rate, with a fitted linear regression model of R2 = 0.91, death rate = 0.63(year) − 1267 (P = .0475). In 2021, there were 4752 pediatric firearm deaths, translating to a rate of 5.8 per 100 000 persons, representing an 8.8% increase in the rate from 2020. Of the 2021 pediatric firearm deaths, 64.3% were homicides, 29.9% were suicides, and 3.5% resulted from unintentional injury. Other deaths were categorized as undetermined or legal intervention (2.0% and 0.3%, respectively). The firearm homicide death rate increased by 5.7%, from 3.5 to 3.7 per 100 000 persons from 2020 to 2021. The firearm suicide rate also had a slight increase from 1.6 to 1.7 per 100 000 persons from 2020 to 2021. Unintentional and undetermined firearm injuries represented a small proportion of deaths, with relatively stable death rates (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics Among Pediatric Firearm Mortalities

| Total N (Crude Death Rate) | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total firearm deaths | 3342 (4.1) | 3390 (4.2) | 4368 (5.4) | 4752 (5.8) |

| Intent | ||||

| Homicide | 1831 (2.2) | 2023 (2.5) | 2811 (3.5) | 3057 (3.7) |

| Suicide | 1297 (1.6) | 1167 (1.4) | 1293 (1.6) | 1421 (1.7) |

| Unintentional | 116 (0.1) | 117 (0.1) | 149 (0.2) | 168 (0.2) |

| Undetermined/other | 98 (0.1) | 83 (0.1) | 115 (0.1) | 106 (0.1) |

| Age | ||||

| 0–4 y | 91 (0.6) | 86 (0.4) | 135 (0.7) | 153 (0.8) |

| 5–9 y | 70 (0.3) | 82 (0.4) | 122 (0.6) | 138 (0.7) |

| 10–14 y | 367 (1.8) | 342 (1.6) | 494 (2.4) | 534 (2.5) |

| 15–19 y | 2807 (13.3) | 2880 (13.7) | 3617 (17.3) | 3927 (18.2) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 1791 (3.0) | 1686 (2.9) | 2067 (3.6) | 2123 (3.6) |

| Black | 1346 (10.9) | 1478 (12.0) | 2056 (16.6) | 2369 (18.9) |

| Asian American | 55 (1.2) | 50 (1.1) | 51 (1.1) | 64 (1.4) |

| AIAN | 48 (3.7) | 53 (4.1) | 74 (5.4) | 57 (4.1) |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 (*) | 18 (*) | 0 (*) | 0 (*) |

| >1 race | 93 (2.1) | 105 (2.4) | 112 (2.4) | 132 (2.8) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 553 (2.7) | 578 (2.8) | 790 (3.8) | 834 (4.0) |

| Non-Hispanic | 2785 (4.5) | 2808 (4.6) | 3751 (5.9) | 3911 (6.4) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 2858 (6.8) | 2904 (7.0) | 3772 (9.1) | 4031 (9.6) |

| Female | 484 (1.2) | 486 (1.2) | 596 (1.5) | 721 (1.8) |

Absolute mortalities <20 have crude death rates unavailable or unreliable (*). Crude death rate is deaths per 100 000 persons.

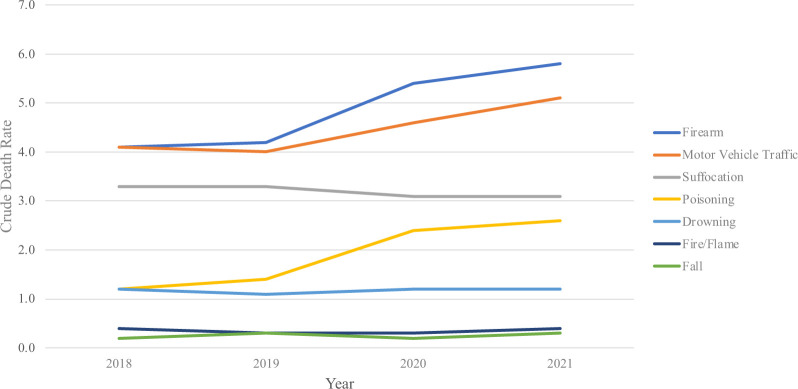

In 2021, firearms remained the leading cause of death among children and adolescents compared with other injury-related causes of death (Fig 1). When stratifying injury-related causes of death by age, firearms were the leading cause of death at ages 14 years and above in 2018 and 2019, 13 years and above in 2020, and 12 years and above in 2021. The firearm death rate per 100 000 persons increased by 0.1 from 2018 to 2019, by 1.2 from 2019 to 2020, and by 0.4 from 2020 to 2021. Comparatively, there was no change in death rate for pediatric drowning or suffocation from 2020 to 2021. Despite increases in other injury-related causes of death from 2018 to 2021, the firearm death rate per 100 000 persons increased by an overall greater amount (1.7) compared with motor vehicle accidents (1.0) and poisonings (1.5).

FIGURE 1.

Leading causes of injury-related mortality in children from 2018 to 2021. Crude death rate is rate of death per 100 000 persons.

2. Age Disparities

Older adolescents aged 15 to 19 years accounted for 82.6% of firearm deaths in 2021, with a 5.2% increase in the death rate per 100 000 persons from 2020 (Table 1). In younger children, the firearm death rate per 100 000 was lower (aged 0–4 years, 0.8, and aged 5–9 years, 0.7). Homicide was the greatest driver of all pediatric firearm deaths. The firearm homicide rate in young children (aged 0–4 years and 5–9 years) was consistently lower than adolescents (aged 10–14 years and 15–19 years). However, all ages had an increase in firearm-related homicides, including a 66% increase from 2018 to 2021 in children of both subgroups aged 0 to 4 years and aged 5 to 9 years, a 100% increase in children aged 10 to 14 years, and a 62% increase in adolescents aged 15 to 19 years. Additionally, firearm suicides were only seen in children aged 10 to 19 years, with a greater death rate per 100 000 persons among older adolescents. Both age groups had relatively stable suicide death rates per 100 000 persons since 2018 (1.3–1.6 aged 10–14 years, and 4.7–5.5 aged 15–19 years). Unintentional as well as undetermined and legal intervention-related injuries contributed little to overall firearm deaths, and rates remained stable.

3. Gender Disparities

Males accounted for 84.8% of all pediatric firearm mortalities in 2021, with a death rate of 9.6 per 100 000 persons, increased from 6.8 in 2018. Although contributing little to total firearm mortalities, the firearm death rate in females increased from 1.2 to 1.8 per 100 000 persons over the 2018–2021 study period. By intent, males accounted for the majority (84.2%) of firearm homicides in 2021, translating to a rate of 6.1 per 100 000 male children, increased from 3.7 in 2018. Firearm suicide also disproportionately affected males, accounting for 86.2% of all firearm suicide deaths in 2021, with the suicide rate per 100 000 males relatively stable from 2.7 in 2018 to 2.9 in 2021. Rates of unintentional and undetermined firearm deaths in both males and females remained stable from 2018 to 2021(Supplemental Table 2).

4. Racial and Ethnic Disparities

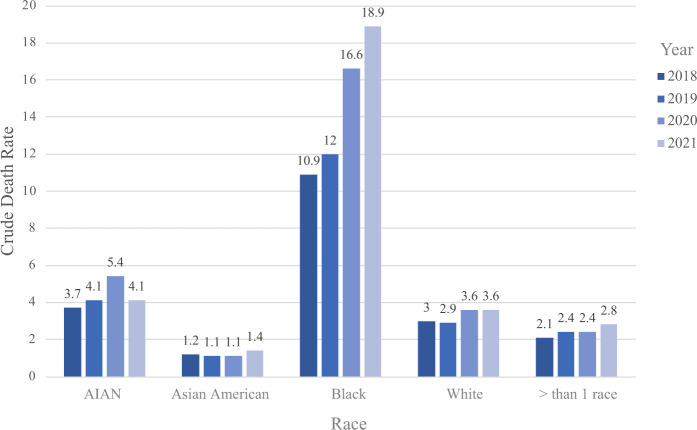

Black children were disproportionately affected by firearm mortalities and accounted for the greatest increase in death rate, from 16.6 to 18.9 per 100 000 persons from 2020 to 2021, increased from 10.9 in 2018 (Fig 2). By ethnicity, Hispanic children had a lower overall firearm death rate per 100 000 persons (4.0) compared with non-Hispanic children (6.4) in 2021. Both ethnicities saw an increase in death rate since 2018 (4.5–6.4 per 100 000 non-Hispanic children and 2.7–4.0 per 100 000 Hispanic children).

FIGURE 2.

Pediatric firearm mortality by race. Crude death rate is rate of death per 100 000 persons.

With respect to firearm homicides, in 2021, the death rate was 11 times higher for Black children compared with white children (16.3 vs 1.5 per 100 000 persons, respectively), representing the largest disparity gap in the 4 years of this study. From 2020 to 2021, there was a 12.4% increase in the firearm homicide rate among Black children (14.5–16.3 per 100 000), and a 13.3% increase in multiracial firearm homicides. In contrast, white, Asian American, and AIAN children saw moderate to no increases in firearm homicide rates from 2020 to 2021. Similarly, for both Hispanic and non-Hispanic children, firearm death rates were primarily driven by homicides. There was a 7.7% increase (2.6–2.8) in homicide rate per 100 000 Hispanic children and an 8.1% (3.7–4.0) increase in homicide rate of non-Hispanic children from 2020 to 2021.

For firearm suicides, white children accounted for 78.4% of all firearm suicide deaths in 2021, and Black children comprised 14.1%. Although contributing to a small absolute number of suicides, AIAN children had the highest firearm suicide rate (2.0 per 100 000 persons) in 2021. Notably, this rate represented a decrease from 2.6 in 2020. Contrarily, firearm suicides by white and Black children increased from 2020 to 2021 (increase by 0.2 and 0.3 per 100 000 persons, respectively). Asian American and multiracial children had low rates of firearm suicide. Firearm suicides also increased in both Hispanic and non-Hispanic children, with higher death rates observed among non-Hispanic children compared with Hispanic children (2.0 vs 1.0 per 100 000 persons, respectively). Unintentional firearm deaths remained stable and at low rates across all races and ethnicities. Firearm death rates by intent, race, ethnicity, age, and gender are summarized in Supplemental Table 2.

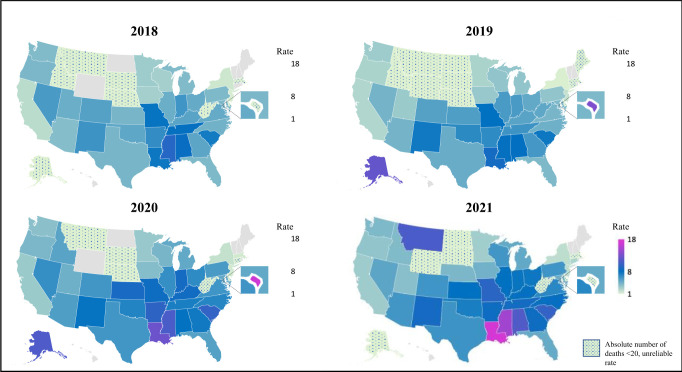

5. Geographic Disparities

Pediatric firearm deaths varied substantially by geographic location (Fig 3). In 2021, firearm mortalities were largely concentrated in Southern states. Louisiana had the highest death rate per 100 000 persons (17.0), followed by Mississippi (14.8), Alabama (11.4), Montana (11.1), and South Carolina (10.2). From 2018 to 2021, the 5 states with the highest increases in death rates were Louisiana (123.7%), Wisconsin (110.7%), Kansas (90.5%), North Carolina (88.6%), and Illinois (73.9%). There was a significant reduction in firearm death rates in the District of Columbia and Alaska from 2020 to 2021, decreasing from an elevated 11.3 and 12.2 per 100 000 persons, respectively, to unreliable levels (<20 total deaths) in 2021.

FIGURE 3.

Pediatric firearm mortality rate by state and year from 2018 to 2021. States with absolute mortalities <20 are grayed out because of unreliable crude death rates (these include Arkansas, Delaware, Hawaii, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Vermont, West Virginia, Wyoming, and District of Columbia).

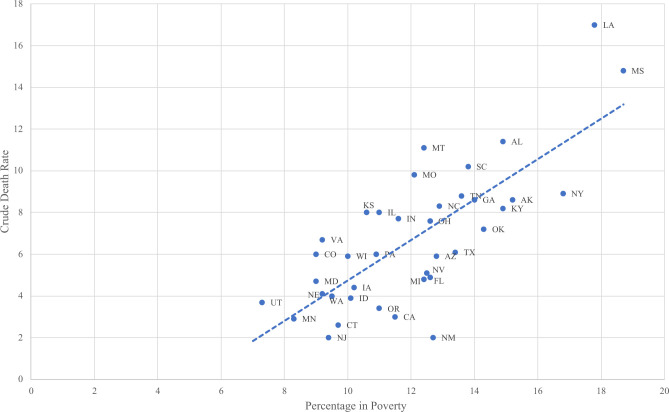

6. Socioeconomic Disparities

The percentage of residents living in poverty was positively correlated with an increased firearm death rate per 100 000 persons in 2021 (Pearson R = 0.75, P < .001) (Fig 4). Although a weakly positive correlation existed from 2018 to 2020, this correlation was most notable in 2021 (R = 0.62 and P < .001 in 2020, R = 0.49 and P = .002 in 2019, and R = 0.63 and P < .001 in 2018). Of note, 12 states and the District of Columbia, which had ranges of poverty levels from 7% (New Hampshire) to 15.8% (West Virginia), were not included because they had an unreliable death rate owing to reported mortality numbers of <20.

FIGURE 4.

Correlation of poverty and pediatric firearm mortality by state in 2021. Crude death rate is death per 100 000 persons. Percentage in poverty calculated from 2020 US Census. R = 0.76 (P < .001).

Discussion

Firearms continue to be the leading cause of death among US children and adolescents. This is the first study exclusively focused on children demonstrating increased firearm deaths and disparities in 2021, beyond the stark numbers previously seen in 2020. The large uptick in pediatric firearm-related deaths in 2020 garnered national attention, with many theorizing the increase to be because of the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and exacerbation of root causes.10–13 We found that, prepandemic, in 2018 and 2019, the firearm mortality rate was 4.1, rose to 5.4 in 2020, and continued to increase to 5.8 in 2021. Strikingly, although initial pandemic-related fears and anxiety have dampened, firearm mortalities persisted as the leading cause of death in children and adolescents in 2021.

Disparities in pediatric firearm deaths have widened significantly.20 Adolescents and males were most affected by firearm deaths over the study period. Although this is driven by homicides, males also accounted for most firearm suicides. This long-standing gender gap has been documented previously, with males accounting for 82% of all firearm childhood deaths from 2002 to 2014, similar to the 85% identified in this study.2 Historically, female children were more likely to present to an emergency department with less lethal self-inflicted injuries than male counterparts, which may account for decreased firearm use in females with suicidality.21 Further, for firearm injuries of all intents, previous studies demonstrated increased risk of hospital inpatient firearm-related mortality among males compared with females.2,7 Despite the documented dominance of male deaths by firearm, the firearm mortality death rate is increasing in both males and females, demonstrating a concerning upward trend of firearm deaths overall.

Racial disparities in firearm mortalities have also worsened significantly, with Black children accounting for half of firearm deaths in 2021 and exhibiting the greatest increase in death rate from 2020 to 2021. This is consistent with previous data demonstrating Black Americans have represented the majority of those hospitalized with firearm injury.7,22–24 Alarmingly, from 2012 to 2014, the annual firearm homicide rate for Black children was twice as high as AIAN children, 4 times as high as Hispanic children, and 10 times higher than white and Asian American children.2 This disparity has only worsened. In 2021, Black children accounted for the greatest firearm homicide rate, increasing >7 times the rate of increase over any other race. Addressing these widening racial disparities requires dedicated strategies that dismantle drivers of structural violence.25 For pediatric firearm suicides, AIAN children had the highest annual death rate from 2018 to 2021, followed by white and Black children. This trend is consistent with over a decade ago, when the death rate of AIAN and white suicides was 4 times as high as Black or Hispanic children.2 Interestingly, AIAN children had a decrease in suicide rates in 2021. In contrast, Black children had increasing suicide rates from 2018 to 2021, narrowing the gap significantly. It is critical that ample attention be given to preventing firearm suicides among children across racial groups.

Geographic and socioeconomic disparities of pediatric firearm deaths have also increased. States with high baseline death rates showed greater increases in 2021, particularly in the Southeastern United States and in some Western states, and the burden of firearm death across Southern states is worsening.2,7 State variability in social determinants of health, inequity, firearm access, legislation, and access to preventative strategies (violence intervention, suicide prevention, firearm safety) may all contribute to these disparities.4,26 For example, in Missouri, the repeal of universal background checks led to a sharp increase in firearm deaths the year after, 29% above the projected rate.27 Missouri, which already had 1 of the highest pediatric firearm death rates, as well as other Southern states, continued to see increases in death rates over our study period. State poverty levels were also found to be positively correlated with higher pediatric firearm death rates, and this correlation strengthened in 2021. Although these are correlations and cannot imply causation, this trend is consistent with previous findings demonstrating increased firearm-related hospitalization among children living in lower-income neighborhoods.8,28 Although we found a moderate correlation, this does not account for inner-state variations at the neighborhood level. Improving our understanding of pediatric firearm death distributions within states and potential root causes is important in informing public health strategies.

Several limitations of this study exist. The CDC data set collects deaths and codes on the basis of International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, codes, which may inaccurately classify the data, specifically intent.29 Furthermore, the data sources used only contain certain demographics and macro-level characteristics, limiting more detailed analyses. For example, the nuances of state and local policies, access to firearms, circumstances surrounding firearm deaths, and influence of local poverty levels were unable to be evaluated. In addition, although the death rate correlation with poverty level is important, our analysis is unable to account for other known factors that may influence state poverty and state firearm deaths. Finally, because this study utilizes CDC WONDER data, nonfatal firearm injuries are not included in these analyses. The need for improved firearm injury and mortality data has been recognized. Examples include a call to action for the creation of a Pediatric Applied Research Network30 and a recent national opinion research center (NORC) report describing the creation of a new frameworks for firearm data infrastructure.31 National efforts are underway to improve data capture on nonfatal firearm injuries for future studies (CDC Firearm Injury Surveillance Through Emergency Rooms and Cardiff model.)32,33 Despite the need for better data, uncovering broader trends in firearm mortalities provides critical knowledge to inform robust local examination of firearm deaths, review of local policies, and implementation focused on risk factors.

Conclusions

Firearms continue to be the leading cause of death among US children and adolescents. With the unexpected sharp uptick of pediatric firearm deaths noted in 2020, rates did not return to prepandemic levels in 2021, but rather continued to increase and surpassed initial pandemic levels. Homicide accounts for the largest burden of pediatric firearm deaths, with substantial increases from 2018 to 2021. Sociodemographic and geographic disparities in firearm deaths are worsening, and adolescents and Black males continue to be disproportionately affected. These findings highlight the necessity and urgency of real-time epidemiologic surveillance of this epidemic and implementation of evidence-informed strategies to prevent pediatric firearm fatalities among children and adolescents at highest risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Microsoft product GeoNames was used for creation of maps.

Glossary

- AIAN

American Indian or Alaskan Native

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- WONDER

Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research

Footnotes

Drs Roberts and Nofi and Ms Cornell conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the initial manuscript, and edited and revised the final manuscript; Dr Kapoor and Ms Harrison critically reviewed and revised the final manuscript; Dr Sathya conceptualized and designed the study, interpreted the data, and edited and revised the final manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FUNDING: Drs Sathya, Harrison, and Kapoor are funded by the National Institutes of Health and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development for a project titled “Evaluating Implementation and Feasibility of Evidence-Based Universal Screening and Intervention Strategies for Firearm Injury and Mortality Prevention Among Youth and Adults in Emergency Departments,” grant R61HD104566-01. The funders had no role in the design or conduct of this study. All other authors received no external funding.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Goldstick JE, Cunningham RM, Carter PM. Current causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(20):1955–1956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fowler KA, Dahlberg LL, Haileyesus T, Gutierrez C, Bacon S. Childhood firearm injuries in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20163486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schleimer JP, McCort CD, Shev AB, et al. Firearm purchasing and firearm violence during the coronavirus pandemic in the United States: a cross-sectional study. Inj Epidemiol. 2021;8(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Monuteaux MC, Azrael D, Miller M. Association of increased safe household firearm storage with firearm suicide and unintentional death among US youths. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(7):657–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Poulson M, Neufeld MY, Dechert T, Allee L, Kenzik KM. Historic redlining, structural racism, and firearm violence: a structural equation modeling approach. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2021;3:100052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Olufajo OA, Zeineddin A, Nonez H, et al. Trends in firearm injuries among children and teenagers in the United States. J Surg Res. 2020;245:529–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hughes BD, Cummins CB, Shan Y, Mehta HB, Radhakrishnan RS, Bowen-Jallow KA. Pediatric firearm injuries: racial disparities and predictors of health care outcomes. J Pediatr Surg. 2020;55(8):1596–1603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barrett JT, Lee LK, Monuteaux MC, Farrell CA, Hoffmann JA, Fleegler EW. Association of county-level poverty and inequities with firearm-related mortality in US youth. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(2):e214822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Quiroz HJ, Casey LC, Parreco JP, et al. Human and economic costs of pediatric firearm injury. J Pediatr Surg. 2020;55(5):944–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peña PA, Jena A. Child deaths by gun violence in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(8):e2225339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cohen JS, Donnelly K, Patel SJ, et al. Firearms injuries involving young children in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics. 2021;148(1):e2020042697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Iantorno SE, Swendiman RA, Bucher BT, Russell KW. Surge in pediatric firearm injuries presenting to US children’s hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2023;177(2):204–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sun S, Cao W, Ge Y, Siegel M, Wellenius GA. Analysis of firearm violence during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e229393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Center for Health Statistics mortality data on CDC WONDER. Available at: https://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd.html. Accessed December 4, 2022

- 15. Cunningham RM, Walton MA, Carter PM. The major causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(25):2468–2475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tracy ET, Englum BR, Barbas AS, Foley C, Rice HE, Shapiro ML. Pediatric injury patterns by year of age. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48(6):1384–1388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hedegaard H, Johnson RL, Garnett MF, Thomas KE. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) external cause-of-injury framework for categorizing mechanism and intent of injury. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2019; (136):1–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. GeoNames . Available at: https://www.geonames.org/. Accessed December 4, 2022

- 19. US Census Bureau . Small area income and poverty estimates (SAIPE). Available at: https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/saipe/#/. Accessed October 4, 2022

- 20. Smart R, Schell TL, Morral AR, Nicosia N. Geographic disparities in rising rates of firearm-related homicide. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(2):189–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sulyman N, Kim MK, Rampa S, Allareddy V, Nalliah RP, Allareddy V. Self-inflicted injuries among children in United States–estimates from a nationwide emergency department sample. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martin CA, Unni P, Landman MP, et al. Race disparities in firearm injuries and outcomes among Tennessee children. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47(6):1196–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Urrechaga EM, Stoler J, Quinn K, et al. Geodemographic analysis of pediatric firearm injuries in Miami, FL. J Pediatr Surg. 2021;56(1):159–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sakran JV, Nance M, Riall T, Asmar S, Chehab M, Joseph B. Pediatric firearm injuries and fatalities: do racial disparities exist? Ann Surg. 2020;272(4):556–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boeck MA, Strong B, Campbell A. Disparities in firearm injury: consequences of structural violence. Curr Trauma Rep. 2020;6(1):10–22 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee LK, Fleegler EW, Farrell C, et al. Firearm laws and firearm homicides: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):106–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Webster D, Crifasi CK, Vernick JS. Effects of the repeal of Missouri’s handgun purchaser licensing law on homicides. J Urban Health. 2014;91(2):293–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kalesan B, Mobily ME, Keiser O, Fagan JA, Galea S. Firearm legislation and firearm mortality in the USA: a cross-sectional, state-level study. Lancet. 2016;387(10030):1847–1855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barber C, Goralnick E, Miller M. The problem with ICD-coded firearm injuries. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(8):1132–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Upperman JS, Burd R, Cox C, Ehrlich P, Mooney D, Groner JI. Pediatric-applied trauma research network: a call to action. J Trauma. 2010;69(5):1304–1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. NORC at the University of Chicago . A blueprint for collecting national firearms data. Available at: https://www.norc.org/Research/Projects/Pages/expert-panel-on-firearms-data-infrastructure.aspx. Accessed March 7, 2023

- 32. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Funded surveillance. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/firearms/funded-surveillance.html. Accessed March 7, 2023

- 33. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . What is the Cardiff Violence Prevention Model? Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/fundedprograms/cardiffmodel/whatis.html. Accessed March 7, 2023

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.