Abstract

Ketamine and esketamine are efficacious for treatment resistant depression. Unlike other antidepressants, ketamine lacks a therapeutic delay and decreases the risk for suicide. This cross-sectional study geographically characterized ketamine and esketamine prescribing to United States (US) Medicaid patients. Ketamine and esketamine prescription rates and spending per state were obtained. Between 2009-2020, ketamine prescribing rates peaked in 2013 followed by a general decline. For ketamine and esketamine in 2019, Montana (967/million enrollees) and Indiana (425) showed significantly higher prescription rates, respectively, relative to the national average. A total of 21 states prescribed neither ketamine nor esketamine in 2019. There was a 121.3% increase in esketamine prescriptions from 2019 to 2020. North Dakota (1,423) and North Carolina (1,094) were significantly elevated relative to the average state for esketamine in 2020. Ten states prescribed neither ketamine nor esketamine in 2020. Medicaid programs in 2020 spent 72.7 fold more for esketamine ($25.3 million) than on ketamine (0.3 million). Despite the effectiveness of ketamine and esketamine for treatment resistant depression and anti-suicidal properties, their use among Medicaid patients was limited and highly variable in many areas of the US. Further research to better understand the origins of this state-level variation is needed.

Introduction

Suicide rates continue to increase in the United States (US) marking the presence of a suicide epidemic. Suicide was the second leading cause of death for people aged 10-34 in 2019 (US Department of Health & Human Service, 2022). Suicide ranked as the 10th leading cause of death with 4.8% of adults having thoughts of suicide and 0.6% (1,969,200) reporting having had attempted suicide in the past year (US Department of Health & Human Service, 2022). The rate of serious suicide attempt ED visits increased by 50.6% in adolescent girls in 2021 compared with 2019 (Yard, Radhakrishnan, Ballesteros, et al. 2021). Unfortunately, traditional antidepressants are often ineffective in preventing suicide linked to depression for three reasons. First, treatment resistant depression, or failure to respond to traditional antidepressants, is present in up to two-thirds of patients (Howland, 2008). Second, a time lag of weeks to months delays the onset of therapeutic effects. Third, traditional antidepressants have been found to counterintuitively increase the risk of suicidality in the first month of therapy in patients who are under 25. This effect was not found in adults and a protective effect was observed in geriatric adults, emphasizing age related differences in suicidality and response to these medications (Nischal, Tripathi, Nischal et al. 2012).

Ketamine, a well-known anesthetic agent, has gained attention as an antidepressant using a novel mechanism of action and is very useful for reducing suicidal ideation (Dadiomov & Lee, 2019). Its absence of therapeutic delay and effectiveness for treatment-resistant depression are well-suited for those at risk of suicide (Duman, 2018). By being effective in both major unipolar and bipolar depressive episodes, unlike other antidepressants, it is useful for depression even when the diagnostic picture is unclear. Extensive attention and research regarding the efficacy, dosing schedule, and clinical utility of ketamine is evaluated using randomized control trials with nationwide effort to better understand how this medication can best treat depression. (Short et al., 2018; Lapidus et al., 2014; Zarate et al., 2006; Acevedo-Diaz et al., 2020) Ketamine may be administered orally, sublingually, transmucosally, intranasally, intravenously, intramuscularly, and subcutaneously; typically, ketamine is delivered via IV in the treatment of depression. Although some patients may require doses as low as 0.1 mg/kg and others as high as 0.75 mg/kg, ketamine is typically administered intravenously in the amount of 0.5 mg/kg. Ketamine sessions typically last 40 minutes and involve intravenous administration. However, it may be administered either quickly (in a bolus dosage in 2 minutes) or slowly (over the course of 100 minutes). Depending on the intensity of depression, treatment can range from a single session to multiple sessions, repeated once in 2 to 3 days for 4 to 6 sessions during the acute phase (Andrade, 2017). In March of 2019, the FDA issued a conditional approval of esketamine, a stereoisomer of ketamine, a nasal spray administered under direct supervision of a medical provider. It is approved in the US for use in patients with treatment resistant depression or with depression and acute suicidality. A moderately well powered clinical trial (N = 63) demonstrated that esketamine (0.25 mg/kg iv) was non-inferior to ketamine (0.5 mg/kg iv) for treatment resistant depression (Correia-Melo, Leala, Vieiraa, et al. 2020). The discovery of these new indications for ketamine is a landmark development as existing antidepressants have a black-box warning for young-adults for increasing suicide. Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) is regarded as a highly efficacious option for treatment resistant depression, though it is generally recognized as underutilized (Espinoza & Kellner, 2022), particularly among minorities (Black Parker, McCall, Spearman-McCarthy et al. 2021; Jones, Salemi, Dongawar, et al. 2019). However, the efficacy of ECT in the prevention of suicide has been challenged by a recent paper that showed ECT did not decrease the risk of death by suicide (Watts, Peltzman & Shiner, 2022).

The objective of this study was to examine patterns in ketamine and esketamine prescription rates throughout the US among Medicaid patients. Given the recency of esketamine to the market and its current high visibility in the field (Duman, 2018), these patterns may be particularly informative.

METHODS

Ketamine and esketamine prescription rates and costs were obtained from the Medicaid State Drug Utilization database (Medicaid, 2022). Medicaid is a joint federal and state program that provides coverage for 75 million people, approximately 21% of the US population. All states provide coverage for outpatient prescription drugs. We evaluated the Medicaid State Drug Utilization database for total outpatient ketamine (2009 – 2020) and esketamine (2019 – 2020) prescriptions per state. Prescription rates were reported per 1,000,000 Medicaid enrollees. Formulations were categorized by National Drug Codes (Supplemental Appendix A & B) and by route of administration (nasal vs injection). Procedures were approved as exempt by the Geisinger and the University of New England IRBs.

We calculated the percent change in prescribing over time, and a 95% confidence interval (mean ± 1.96*SD) with states outside this range interpreted as significantly different from the mean. We also calculated the ratio of the highest to lowest (non-zero) prescribing rate, and the ratio of total Medicaid spending for esketamine relative to ketamine. We analyzed the data and constructed figures using SAS, JMP and GraphPad Prism.

RESULTS

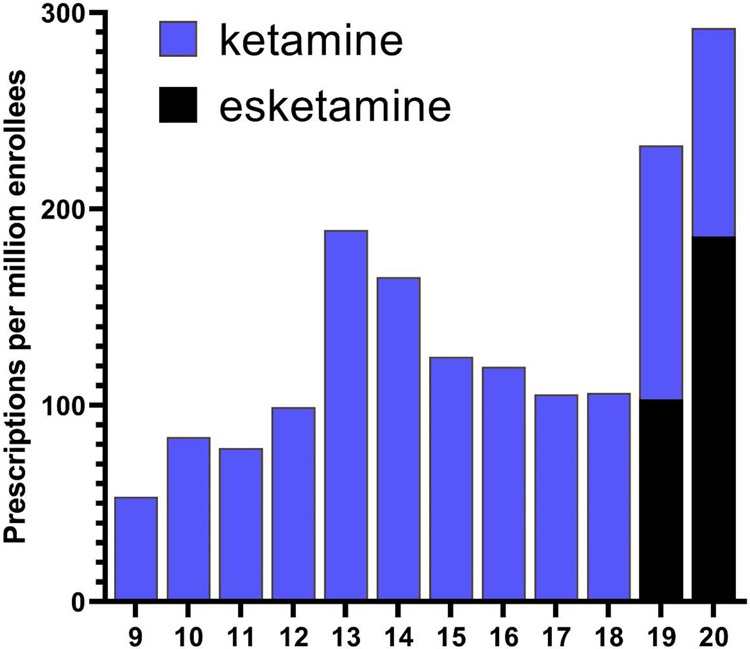

Figure 1 shows that prescribing rates for ketamine from 2009 to 2020 were elevated in 2013 with a 91.2% increase compared to 2012. This was followed by a gradual decrease from 2014 to 2018. With the approval of esketamine, the total (i.e. ketamine and esketamine) prescriptions tripled from 2018 (106/million enrollees) to 2020 (292/million). Examination of the quarterly prescriptions nationally revealed that ketamine was relatively stable except for a 31.2% reduction from the fourth quarter of 2019 (56.6) until the first quarter of 2020 (38.9). Esketamine increased 4.5-fold between the second quarter of 2019 (23.5) until the fourth quarter of 2020 (106.7, Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1.

National prescription rate of ketamine and esketamine to Medicaid patients from 2009 to 2020.

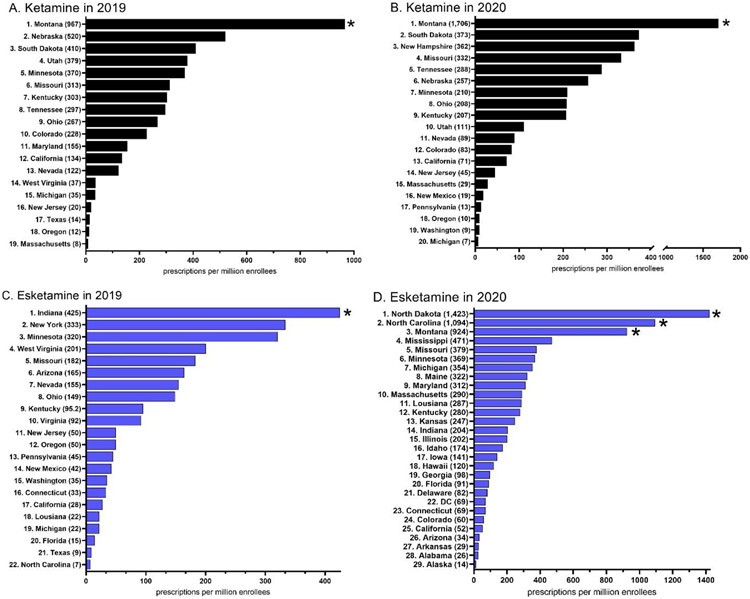

There were 27,238 prescriptions nationally for ketamine and esketamine in 2019. Of these, 12,668 prescriptions (46.5%) were for esketamine nasal spray and 14,570 (53.5%) for ketamine injections. Pronounced geographical differences were also identified. For ketamine, Montana (967.3) showed a statistically significant higher rate of prescription relative to the national average (Figure 2A). There was a 116-fold higher rate of prescriptions in Montana relative to the lowest state (MA = 8.3). States in the southern US from New Mexico to South Carolina had no ketamine prescriptions (Supplemental Figure 2). For esketamine, Indiana (424.6) showed a significantly higher rate of prescription which was also 61-fold higher than the lowest state (Supplemental Figure 2). Twenty states (AK, AL, AR, DE, GA, HI, IA, ID, IL, KS, ME, MS, ND, NH, OK, RI, SC, VT, WI, WY) and Washington DC prescribed neither ketamine nor esketamine (Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Ketamine (A, C) and esketamine (B, D) prescription rate per state to Medicaid patients. States not shown had a value of 0. * p < .05 vs the state average.

There were 40,765 prescriptions for ketamine and esketamine in 2020. Esketamine (28,037) was more than double that of ketamine (12,728). Montana (1,705.6) was significantly higher than the national average and was 245-fold higher than the lowest state (Michigan = 7.0, Figure 2B) for ketamine. States that were located at or below the 35° latitude (Arizona proceeding east to South Carolina) had the lowest prescribing (Supplemental Figure 3). Three-states, North Dakota, North Carolina, and Montana were significantly elevated for esketamine in 2020. There was a 104-fold difference between the highest (North Dakota = 1,423.0) and lowest (Alaska = 13.7) states (Figure 2D, Supplemental Figure 4). Ten states (NY, OK, RI, SC, TX, VI, VT, WV, WI, & WY) prescribed neither ketamine nor esketamine.

The total spending by state Medicaid programs was 14.2 fold greater for esketamine ($5.1 million) than ketamine ($0.4 million) in 2019. This increased to 72.7 fold higher for esketamine ($25.3 million) than ketamine ($0.3 million) in 2020.

DISCUSSION

There are two key findings from this report. First was the increase in esketamine relative to ketamine prescribing to Medicaid patients. Esketamine, in conjunction with an oral antidepressant, received FDA-approval for the treatment of adults with treatment-resistant depression on March 5, 2019. Esketamine prescriptions were less than half (44.2%) those of ketamine in 2019. The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study revealed that only one-third of depressed patients experienced a remission after receiving the first-line antidepressant (Howland, 2008). Use of ketamine and esketamine when expressed relative to the ubiquity of depression and the number of Medicaid enrollees was modest. Second, the state-level differences in esketamine and ketamine prescription rates were pronounced. For example, one state, Indiana prescribed 25% of the national total esketamine in 2019. At the beginning of 2019, quarterly esketamine prescribing was, as anticipated, quite limited, but as the year progressed, a subset of states quickly adapted to use of esketamine. This was perhaps due to increasing evidence (Aan Het Rot, Zarate, Charney, et al. 2013; Correia-Melo et al. 2020; Dadiomov & Lee, 2019; Duman, 2018) and wider distribution of trial results, and the rapid establishment of protocols and procedures that meet the FDA Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy program requirements for these Schedule III substances. The pronounced differences in esketamine prescribing at a state-level could be attributed to marketing rather than long-standing preset preferences in patients and physicians since this was a new drug to the market.

The identification of the rapid therapeutic and anti-suicidality effects of ketamine is potentially one of the most important developments in psychopharmacology in the past two decades. However, we found that the use of esketamine and ketamine among Medicaid patients was both modest, relative to the prevalence of depression and treatment resistant depression, and extremely variable. This variability is also shown by the absence of ketamine/esketamine prescriptions in two-fifths of US states in an outpatient setting in 2019 and one-fifth of states in 2020. The role of ketamine and esketamine in the US as an antidepressant continues to evolve (Duman, 2018; McIntyre, Rosenblat, Nemeroff, et al. 2021; Murrough et al. 2013; Zarate, Brutsche, Ibrahim L et al. 2012).

Regardless of the underlying reasons, it is interesting that the ketamine and esketamine prescribing are nowhere near as high as one might expect from an antidepressant in a class on its own which overcomes the therapeutic lag of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Among the top three-hundred most prescribed medications, the most prescribed antidepressants were sertraline (number 12 of the top 300 medications), escitalopram (no.19), fluoxetine (no. 20), trazodone (no. 25), duloxetine (no. 26), citalopram (no. 30), venlafaxine (no. 40), paroxetine (no. 78), and nortriptyline (no. 153) (Clin Calc, 2019). While it is not yet conclusive that a paradigm shifting pharmacotherapy has been identified, the rates of prescribing suggest peripheral challenges like the logistics of proper administration or social inertia on the use of this psychoactive and controlled substance that may be causing delays. The COVID-19 pandemic likely also contributed to the limited utilization of these agents. However, there have also been fifteen ketamine/esketamine manuscripts which were subsequently retracted (e.g. use of ketamine in the ER (Larkin & Beautrais, 2017) which may also be contributing to some ambiguity [Supplemental Appendix C]. There are also serious concerns with misuse and the development of tolerance (Gálvez, Adrienne Li, Huggins, et al. 2018; Gerb, Cook, Gochenauer, et al. 2019).

The tremendous costs of esketamine/ketamine including monitoring post administration relative to more traditional treatments (Agboola, Atlas, Touchette, et al. 2020; Maldi, Asellus, Myléus, et al. 2021; Ross & Soeteman, 2020) may explain the hesitance among many states’ Medicaid programs to condone use of these agents. Specifically, esketamine can have a first-year cost of $18,564-$45,591 in Canada with minimal cost reduction in subsequent years, compared to racemic ketamine’s $270-$811 annual cost (Pharmacoeconomic Report, 2021). These dramatic price differences are similar in the US, making esketamine inevitably less cost effective than ketamine as the dosing schedules remain similar (Brendle, Robison, and Malone, 2022). Esketamine prescriptions were double those of ketamine in 2020 while spending was seventy-three-fold higher.

Efficacy of racemic versus pure enantiomer is under question as well. R-ketamine exerted a longer lasting antidepressant effect than S-ketamine in the mouse tail suspension test (Fukumoto, Toki, Iijima, et al. 2017). Similar findings of R-ketamine being more potent or producing longer duration effects than S-ketamine have also been observed in the forced swimming, learned helplessness, and social defeat stress models of depression (Yang, Shirayama, Zhang et al. 2015; Zhang, Li, and Hashimoto, 2014). A direct comparison revealed that 62.1% of patients had an antidepressant response to racemic ketamine relative to only 43.7% to esketamine at one-week, although this difference was not significant (Correia-Melo et al. 2020). The potential fiscal and therapeutic advantages of the racemate over only the S-enantiomer may warrant continued research and monitoring by those who oversee state Medicaid programs and others.

The Medicaid state drug utilization database does not provide information about patient medical history or demographics including race/ethnicity. Therefore, we cannot quantify the portion of ketamine that was used for anesthetic purposes. There have been concerns that Black patients were half as likely to receive ECT as non-Hispanic White patients (Black Parker et al. 2021; Jones et al. 2019). US hospitals in the South and West were less likely than those in the Northeast and Midwest to have ECT available (Black Parker et al. 2021). Future research with electronic medical records will be necessary to evaluate whether these disparities are due to the same factors for ketamine and esketamine. However, the more diverse southern states also prescribed less ketamine (Texas, Arizona, Florida) and esketamine (Texas and Alabama). Follow-up investigations with Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance should also be completed after the results of ketamine/esketamine and ECT comparisons (Brezina, 2017; Dehning, 2021; Dodd & DeSilva, 2018; Qiu & Du, 2020) are completed. We believe that future research could include a trend test when sufficient esketamine data has been gathered in the next few years. Additionally, it would be beneficial to compare costs of an IV program such as ketamine assisted psychotherapy versus prescribing a pill form of antidepressant to provide a more robust understanding of ketamine’s potential value.

In conclusion, this study found that low and extremely regionally disparate, rates of ketamine and esketamine prescribing to Medicaid patients in 2019 and 2020. It will likely be a fruitful endeavor to continue to monitor how use of these rapidly acting agents change and impacts patients in future years.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Software used in this research was provided by the NIEHS (T32 ES007060-31A1). AGA and BJP were supported by HRSA (D34HP31025).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest Statement

BJP was part of an osteoarthritis research team (2019-2021) supported by Pfizer and Eli Lilly. The other authors have no disclosures.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data is available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/prescription-drugs/state-drug-utilization-data/index.html

References

- Aan Het Rot M, Zarate CA Jr, Charney DS, Mathew SJ. Ketamine for depression: Where do we go from here?. Biological Psychiatry 2012; 72(7), 537–547. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Diaz EE, Cavanaugh GW, Greenstein D, Kraus C, Kadriu B, Park L, & Zarate CA Jr (2020). Can ‘floating’predict treatment response to ketamine? Data from three randomized trials of individuals with treatment-resistant depression. Journal of psychiatric research, 130, 280–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agboola F, Atlas SJ, Touchette DR, Fazioli K, Pearson SD. The effectiveness and value of esketamine for the management of treatment-resistant Depression: A summary from the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review’s Midwest Comparative Effectiveness Public Advisory Council. Journal of Managed Care and Specialty Pharmacy 2020; 26(1):16–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade C Ketamine for depression, 4: in what dose, at what rate, by what route, for how long, and at what frequency? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2017;78(7):e852–e857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black Parker C, McCall WV, Spearman-McCarthy EV, Rosenquist P, Cortese N. Clinicians’ racial bias contributing to disparities in electroconvulsive therapy for patients from racial-ethnic minority groups. Psychiatric Services 2021; 72:684–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendle M, Robison R, & Malone DC (2022). Cost-effectiveness of esketamine nasal spray compared to intravenous ketamine for patients with treatment-resistant depression in the US utilizing clinical trial efficacy and real-world effectiveness estimates. Journal of affective disorders, 319, 388–396. 10.1016/j.jad.2022.09.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brezina K ELEKT-D: Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) vs. ketamine in patients with treatment resistant depression (TRD). 2017; NCT03113968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapel JM, Ritchey MD, Zhang D, Wang G. Prevalence and medical costs of chronic diseases among adult Medicaid beneficiaries. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2017; 53(6). 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clin Calc. The top 300 of 2019. Accessed 6/5/2022 at: https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Top300Drugs.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Correia-Melo FS, Leala GC, Vieiraa F, Jesus-Nunesa AP, Mello RP, Magnavita R, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive therapy using esketamine or racemic ketamine for adult treatment-resistant depression: A randomized, double blind, non-inferiority study. J Affective Dis 2020; 264: 527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadiomov D, Lee K. The effects of ketamine on suicidality across various formulations and study settings. Mental Health Clin 2019; 9(1):48–60. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2019.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehning J ECT vs. esketamine (ETES): Electroconvulsive therapy vs. esketamine nasal spray in treatment-resistant depression: A longitudinal, randomized efficacy comparison pilot study. 2021; NCT04924257. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd E, DeSilva M. Ketamine versus electroconvulsive therapy in depression. 2018; NCT03674671. [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS. Ketamine and rapid-acting antidepressants: A new era in the battle against depression and suicide. F1000 Research. 2018; 7:659. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.14344.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza R, Kellner C. Electroconvulsive therapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2022; 386:667–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto K, Toki H, Iijima M, Hashihayata T, Yamaguchi JI, Hashimoto K, et al. Antidepressant potential of (R)-ketamine in rodent models: Comparison with (S)-ketamine. Journal of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics. 2017; 361:9–16. doi.org/ 10.1124/jpet.116.239228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gálvez V, Li A, Huggins C, Glue P, Martin P, Somogyi AA, Alonzo A, et al. Repeated intranasal ketamine for treatment resistant depression – the way to go? Results from a pilot randomised controlled trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2018; 32(4):397–407. doi: 10.1177/0269881118760660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerb SA, Cook JE, Gochenauer AE, Young CY, Fulton LK, Grady AW, Freeman KB. Ketamine tolerance in Sprague–Dawley rats after chronic administration of ketamine, morphine, or cocaine. Comparative Medicine 2019; 69:29–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howland RH. Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D). Part 2: Study outcomes. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & Mental Health Services. 2008; 46(10):21–4. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20081001-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KC, Salemi JL, Dongawar D, Kunik ME, Rodriguez SM, Quach TH, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in receipt of electroconvulsive therapy for elderly patients with a principal diagnosis of depression in inpatient settings. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2019; 27:3 (2019) 266–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidus KA, Levitch CF, Perez AM, Brallier JW, Parides MK, Soleimani L, … & Murrough JW (2014). A randomized controlled trial of intranasal ketamine in major depressive disorder. Biological psychiatry, 76(12), 970–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin GL, Beautrais AL. Retraction of publication: A preliminary naturalistic study of low-dose ketamine for depression and suicide ideation in the Emergency Department. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017; 20(7):611. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyx035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldi KD, Asellus P, Myléus A, Norström F. Cost-utility analysis of esketamine and electroconvulsive therapy in adults with treatment-resistant depression. BMC Psychiatry 2021; 21:610. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03601-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattes J Ketamine after two antidepressants? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2021; 178(12):1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre RS, Rosenblat JD, Nemeroff CB, et al. Synthesizing the evidence for ketamine and esketamine in treatment-resistant depression: an international expert opinion on the available evidence and implementation. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2021; 178:383–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicaid. State Drug Utilization Data. Medicaid. (n.d.). Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/prescription-drugs/state-drug-utilization-data/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabi R Unmet need for treatment of major depression in the US. Psychiatric Services 2003; 60(3):297–305. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrough JW, Iosifescu DV, Chang LC, Al Jurdi RK, Green CE, Perez AM, et al. Antidepressant efficacy of ketamine in treatment-resistant major depression: A two-site randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013; 170(10), 1134–1142. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13030392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nischal A, Tripathi A, Nischal A, Trivedi JK. Suicide and antidepressants: What current evidence indicates. Mens Sana Monographs 2012; 10(1):33–44. doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.87287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacoeconomic Report: Esketamine Hydrochloride (Spravato): (Janssen Inc.): Indication: Major Depressive Disorder in Adults [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2021. Apr. Appendix 1, Cost Comparison Table. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572205 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y, Du G. The effect of S-ketamine for patients undergoing Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT). 2020; NCT04399070. [Google Scholar]

- Retraction Watch. The Retraction Watch Database [Internet]. New York: The Center for Scientific Integrity. 2018. [Cited (2/1/2022)]. Available from: http://retractiondatabase.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Ross EL, Soeteman DL. Cost-effectiveness of esketamine nasal spray for patients with treatment-resistant depression in the United States. Psychiatric Services 2020; 71(10): 988–997. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short B, Fong J, Galvez V, Shelker W, & Loo CK (2018). Side-effects associated with ketamine use in depression: a systematic review. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(1), 65–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Suicide. National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved February 11, 2022, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide [Google Scholar]

- Watts BV, Peltzman T, Shiner B. Electroconvulsive Therapy and Death by Suicide. J Clin Psychiatry. 2022. Apr 13;83(3):21m13886. doi: 10.4088/JCP.21m13886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Shirayama Y, Zhang J, Ren Q, Yao W, Ma M, Dong C, Hashimoto K. R-ketamine: A rapid-onset and sustained antidepressant without psychotomimetic side effects. Translational Psychiatry. 2015; 5: e632–e632. doi.org/ 10.1038/tp.2015.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yard E, Radhakrishnan L, Ballesteros MF, et al. Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12–25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, January 2019–May 2021. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report. 2021;70:888–894. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7024e1externalicon [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarate CA Jr, Brutsche NE, Ibrahim L, Franco-Chaves J, Diazgranados N, Cravchik A, et al. Replication of ketamine's antidepressant efficacy in bipolar depression: A randomized controlled add-on trial. Biological Psychiatry. 2012; 71(11):939–946. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarate CA, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, Brutsche NE, Ameli R, Luckenbaugh DA, … & Manji HK (2006). A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Archives of general psychiatry, 63(8), 856–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Li S, Hashimoto K. R (−)-ketamine shows greater potency and longer lasting antidepressant effects than s (+)-ketamine. Pharmacology Biochemistry & Behavior. 2014; 116:137–141. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data is available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/prescription-drugs/state-drug-utilization-data/index.html