Abstract

Background:

Children with callous-unemotional (CU) traits are at high lifetime risk of antisocial behavior. It is unknown if treatments for disruptive behavior disorders are as effective for children with CU traits (DBD+CU) as those without (DBD-only), nor if treatments directly reduce CU traits. Separate multilevel meta-analyses were conducted to compare treatment effects on DBD symptoms for DBD+CU versus DBD-only children and evaluate direct treatment-related reductions in CU traits, as well as to examine moderating factors for both questions.

Methods:

We systematically searched PsycINFO, PubMed, Cochran Library (Trials), EMBASE, MEDLINE, APA PsycNet, Scopus, and Web of Science. Eligible studies were randomized controlled trials, controlled trials, and uncontrolled studies evaluating child-focused, parenting-focused, pharmacological, family-focused, or multimodal treatments.

Results:

60 studies with 9,405 participants were included (Mage=10.04, SDage=3.89 years, 25.09% female, 44.10% racial/ethnic minority). First, treatment was associated with similar reductions in DBD symptoms for DBD+CU (SMD=1.08, 95% CI=.45, 1.72) and DBD-only (SMD=1.01, 95% CI=.38, 1.64). However, DBD+CU started (SMD=1.18, 95% CI=.57, 1.80) and ended (SMD=.73, p<.001; 95% CI=.43, 1.04) treatment with more DBD symptoms. Second, although there was no overall direct effect of treatment on CU traits (SMD=.09, 95% CI=−.02, .20), there were moderating factors. Significant treatment-related reductions in CU traits were found for studies testing parenting-focused components (SMD=.21, 95% CI=.06, .35), using parent-reported measures (SMD=.16, 95% CI=.04, .28), rated as higher quality (SMD=.26, 95% CI=.13, .39), conducted outside the United States (SMD=.19, 95% CI=.05, .32), and with less than half the sample from a racial/ethnic minority group (SMD=.15, 95% CI=.002, .30).

Conclusions:

DBD+CU children improve with treatment, but their greater DBD symptom severity requires specialized treatment modules that could be implemented following parenting programs. Conclusions are tempered by heterogeneity across studies and scant evidence from randomized controlled trials.

Keywords: callous-unemotional traits, disruptive behavior, intervention, parenting, treatment

Introduction

Disruptive behavior disorders (DBD), including oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD), are a common psychiatric condition of childhood (Merikangas et al., 2022). DBD predict high lifetime risk for antisocial behavior, depression, and substance abuse, and confer vast economic costs through health, justice, and school expenditures (Rivenbark et al., 2018). Effective treatments for DBD include parenting programs that teach behavior management techniques (Kazdin, 1997; Leijten et al., 2022), child-focused programs targeting socioemotional skills (Riise et al., 2021; Van der Stouwe et al., 2021), pharmacotherapy (Balia et al., 2018; Khan et al., 2019), and multimodal programs targeting multiple individual, family, and community factors (Hukkelberg et al., 2022; Littell et al., 2021). However, treatment responsiveness is variable, with some children showing minimal or short-lived improvement (Drugli et al., 2010). Given the devastating individual and societal encumbrances of DBD, effective and personalized treatments are critical.

Variability in treatment responsiveness is attributed to heterogeneity in the etiology and presentation of DBD (Fairchild et al., 2019). Notably, 10–50% of children with DBD have callous-unemotional (CU) traits, defined by a callous, uncaring, and remorseless affective style (Waller et al., 2020). The CU traits construct represents a downward developmental extension of the affective facet of psychopathy (e.g., lack of empathy, shallow affect) (Frick et al., 2014; Waller et al., 2020). CU traits predict risk of violence, psychopathy, and arrest, even when accounting for DBD severity (Hawes et al., 2017; McMahon et al., 2010; Neo & Kimonis, 2021). DBD with CU traits (DBD+CU) is more heritable than DBD without CU traits (DBD-only) (Moore et al., 2019), and is associated with distinct neurobiological and behavioral characteristics, including reduced responsivity to distress, fear, and laughter expressed by others (De Brito et al., 2021; Viding & McCrory, 2019). Along with the historical origins of the construct and the therapeutic nihilism previously associated with psychopathy (Harris & Rice, 2006; Tennent et al., 1993), these features explain why DBD+CU children have traditionally been described as unresponsive to treatment. In particular, reduced sensitivity to environmental cues that signal the need to change behavior (e.g., negative consequences, punishment), lack of motivation for social bonding, and disregard for social rewards pose challenges to the implementation and effectiveness of traditional DBD treatment strategies (Hawes et al., 2014; Herpers et al., 2014).

However, this clinical pessimism has been challenged for psychopathy (Polaschek, 2014; Salekin, 2019; Salekin et al., 2010) and DBD+CU (Hyde et al., 2014; Neuman & Bagner, 2021). Many mental health disorders have reliably-identifiable heritable or neurobiological correlates, which are rarely taken to imply that psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy are not worth pursuing (Salekin et al., 2010). Moreover, clinical pessimism sends harmful messages about treatment to parents, teachers, and clinicians, which can become self-fulfilling (Hyde et al., 2014). Notably, several narrative reviews have concluded that parenting-focused treatments can be effective for DBD+CU (Hawes et al., 2014; Waller et al., 2013; Wilkinson et al., 2016). Accordingly, recent approaches have challenged the notion of treatment “unresponsiveness”, focusing instead on developing adapted treatments to specifically target the socioemotional and interpersonal difficulties associated with CU traits (Dadds et al., 2014; Kimonis et al., 2019). To date, however, no meta-analytic work has tested whether DBD treatments are as effective for DBD+CU versus DBD-only children, identified which treatments components help reduce CU traits, or established whether adapted treatments or adjunctive treatment modules designed specifically for DBD+CU are more effective than traditional treatments alone.

We addressed these questions through a systematic review and comprehensive quantitative integration of the DBD+CU treatment literature. Our multilevel meta-analytic approach allowed us to synthesize multiple effect sizes reported within studies and compare group-level data across studies (Van Den Noortgate & Onghena, 2003). Under our first aim, we synthesized data from studies comparing treatment outcomes for DBD+CU versus DBD-only children. Under our second aim, we synthesized data from studies evaluating whether treatment was directly associated with reductions in CU traits. Finally, a review of DBD treatment moderators reported that initial symptom severity, higher parental engagement, individual administration (vs. group), and targeted (vs. universal) approaches were associated with greater treatment responsiveness (McMahon et al., 2021). Less is known about moderators of treatment effectiveness for CU traits. Thus, under both aims, we explored whether sample (e.g., age, gender, pre-treatment severity), treatment (e.g., type, adapted for CU traits), or study (e.g., design, quality) factors moderated treatment effects.

Methods

Literature Review

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA, Table S1) (Moher et al., 2015) searching the literature from Jan 1, 1980 to May 23, 2022 (OSF, doi, 10.17605/OSF.IO/W2PKU; see Supplemental Methods). We searched PsycINFO, PubMed, Cochrane Library (Trials), EMBASE, MEDLINE, APA PsycNet, Scopus, and Web of Science (search terms, Table S2). Studies were also located by searching reference lists of published systematic reviews.

Inclusion criteria

Included studies evaluated child-focused, parenting-focused, pharmacological, family-focused, or multimodal treatments for DBD. For Aim 1, studies compared treatment outcomes among DBD+CU versus DBD-only groups (i.e., pre-post comparison). For Aim 2, studies evaluated treatment outcomes in CU traits for treatment versus control conditions (i.e., no treatment, treatment-as-usual, or waitlist conditions). We included post hoc analysis of studies with uncontrolled designs. Included studies had a mean age <18 years and assessed DBD symptoms and CU traits using established parent-, child-, clinician, or teacher-reported measures (Table S3). Studies were independently examined by the first, second, and third authors with high reliability from double-screening titles and abstracts (50% of studies; 92% agreement, k=2,121) and full-texts (85% of studies; 98% agreement, k=418). Disagreements were resolved by discussion with the senior author.

Data extraction and coding of moderators

We extracted data on treatment outcomes (e.g., group M and SD, exact p or t-values from between-group analyses). We also coded potentially moderating factors. For sample characteristics, we coded age (i.e., continuously [mean age] and by category: preschool [ages, 3–5], school-aged [ages 6–12], and adolescent [ages 13–18]), gender (% female), ethnic/racial minority (% sample), and sample type (clinic-referred, community-referred, juvenile justice). For treatment characteristics, we coded type (inclusion of parenting-component, child-component, pharmacological, family-component, or multimodal), duration (weeks), frequency (more than weekly or weekly), and use of adjunctive/adapted treatment modules to target CU traits (yes/no). For study characteristics, we coded randomized controlled trial (RCT) design (yes/no), informant (parent, child, or teacher), longer-term follow-up (yes/no), study location, publication year, study quality, and measure to assess CU traits. Measures included the Inventory of Callous-Unemotional traits (ICU; Frick, 2004), CU traits subscale of the Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD; Frick & Hare, 2001), 5 items from the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) used to assess CU traits (for a review, see Waller & Hyde, 2017), and the CU traits factor of the Youth Psychopathic Traits Inventory (Andershed et al., 2002). Moderating factors were treated as missing when not reported within studies.

Quality and Risk of Bias Assessment

We evaluated study quality using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system, which evaluates risk of bias, directness of evidence, heterogeneity of data, precision of effect estimates, and risk of publication bias (Balshem et al., 2011). The GRADE method has four steps: (1) Quality rankings of “high” for randomized controlled trials (RCT), “moderate” for non-randomized controlled trials or open trials, and “low” for observational studies; (2) Downgrading of initial rankings based on risk of bias (e.g., no randomized allocation sequence, lack of pre-registration), inconsistency (e.g., unexplained variability in results between different measures of the same construct), imprecision (e.g., lack of confidence intervals), indirectness of evidence (e.g., indirect comparison of two trial conditions), and publication bias (e.g., industry sponsored, extremely small sample); (3) Upgrading rankings for large effects or dose-response relationships (i.e., proportional to degree of exposure); and (4) Assigning final ratings from “very low”, “low”, “moderate”, to “high” (see Supplemental Results and Table S4). Studies were double coded by the first and second or third author with disagreements resolved by discussion with the last author.

Meta-analyses

Effect sizes were calculated as standard mean differences (SMD or Hedges’ g) (Andrade, 2020) using the ‘metafor’ package for R (R Core Team, 2013; Viechtbauer, 2010). We prioritized effect sizes calculated from descriptive statistics, then author-reported effect sizes, and finally effect sizes calculated from inferential statistics. Study aims were addressed using random effects multilevel meta-analysis and meta-regression, allowing us to evaluate heterogeneity within studies and model dependencies between multiple effect sizes (level 2) nested within treatment groups (level 3) and studies (level 4) (Cheung, 2019; Konstantopoulos, 2011; Van Den Noortgate & Onghena, 2003). We compared the fit for a four-level model (sampling error, effect size, treatment, and study) to three-level (sampling error, effect size, and treatment) and two-level (sampling error and effect size) models, selecting the best-fitting model using established criteria (Fernández-Castilla et al., 2020). For our first aim, we used multilevel meta-analysis to test whether CU traits group (i.e., DBD+CU vs. DBD-only) was related to SMD in a pre-post treatment difference score in DBD symptoms. We ran separate multilevel meta-analyses to test whether the DBD+CU and DBD-only groups differed in pre-treatment and post-treatment DBD symptoms. For our second aim, we ran a multilevel meta-analysis to examine treatment-related reductions in CU traits in studies that compared treatment versus control conditions (i.e., no treatment, treatment-as-usual, or waitlist conditions). In a post hoc analysis, we ran a multilevel meta-analysis examining treatment-related reductions in CU traits (i.e., pre-post treatment changes) reported by studies with uncontrolled designs. We examined risk of publication bias (Duval & Tweedie, 2000; Egger et al., 1997) and conducted a sensitivity analysis by examining outliers for each pooled effect size (see Supplemental Methods). Finally, we examined moderation of treatment outcomes by sample, treatment, and study characteristics. We report coefficients for meta-regression analyses, with representing change in the pooled effect when the moderating variable increases, and (i.e., intercept) indicating SMD for a specific value of the moderator (Dekkers et al., 2022). For significant values, we conducted subgroup analyses. For Aim 1 (i.e., treatment effects for DBD+CU and DBD-only), sample, treatment, and study characteristics were included as additional moderators with representing a change in the pooled effect for DBD+CU vs. DBD-only children, representing a change in the pooled effect with the addition of the moderating variable, and representing change in the pooled effect with the addition of the interaction term between the moderating variable and CU traits group.

Results

Study selection and inclusion

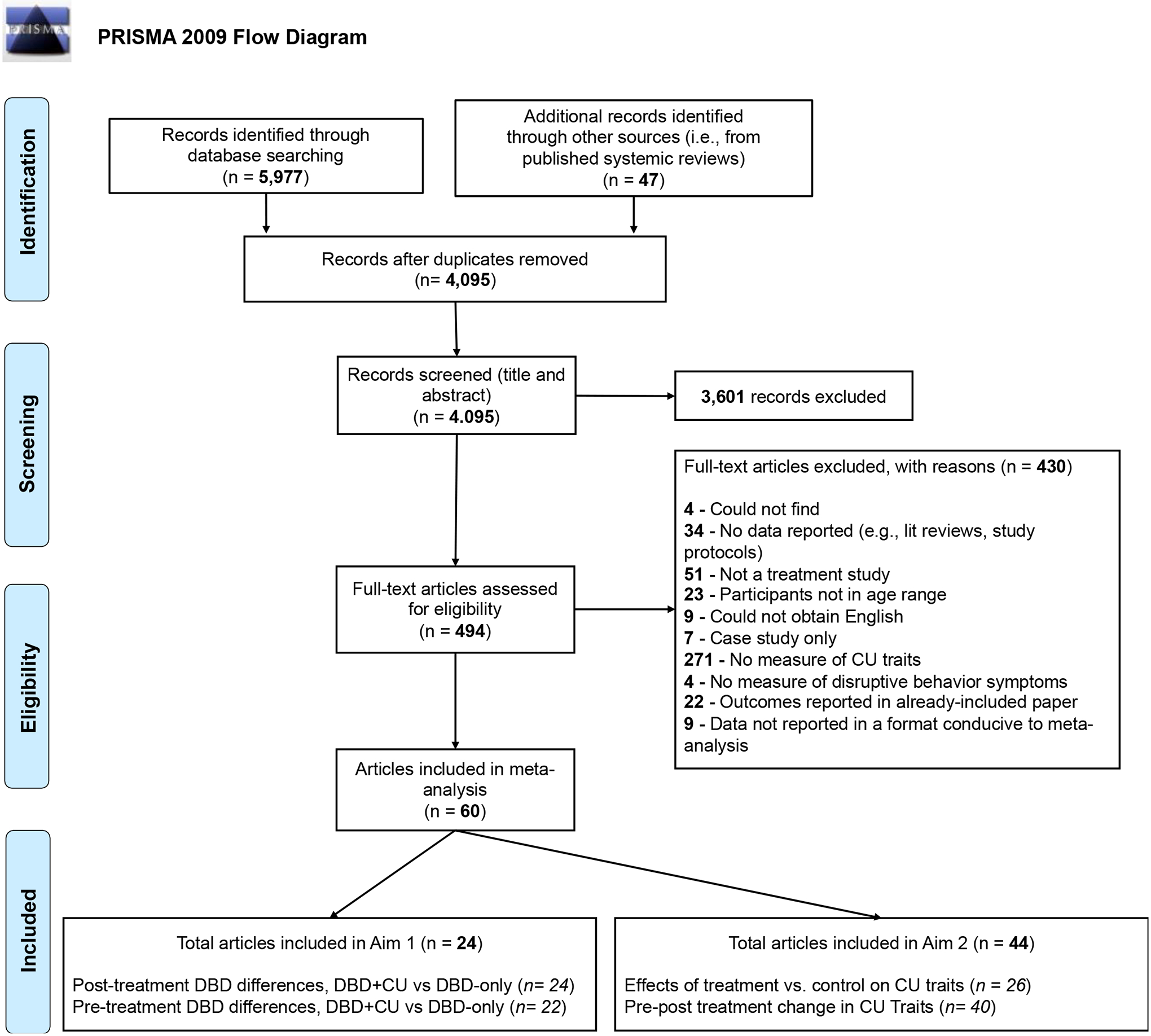

We examined 6,024 records, excluded 1,929 duplicates, screened 2,095 titles and abstracts, and retrieved 494 full-texts (Table S5). Sixty-seven studies met inclusion criteria. We contacted authors for information on 39 of the 67 studies. Responses were received for 30 studies (76.92%) with authors providing usable data for 27 studies. For the 9 studies where authors did not respond, 7 were entirely excluded because they did not report sufficient data to be included, leaving 60 studies (N=9,405 participants) for analyses. The PRISMA flowchart is presented in Figure 1 and Table S6 summarizes characteristics of included studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart documenting excluded and included studies

Note. There was overlap between the articles included across each study aim and meta-analysis. Three articles were included across all aims and meta-analyses (Bryd, 2016; Hyde et al., 2013; Manders et al., 2013). Under Aim 1, two studies did not report pre-treatment DBD symptoms by DBD+CU and DBD-only groups and were excluded from meta-analyses of pre-treatment differences and CU traits moderation of pre-post treatment DBD symptom change. Furthermore, 5 articles included in Aim 1 were also included under Aim 2. Under Aim 2, 22 articles were included across each meta-analysis. Furthermore, under Aim 2, four articles did not present CU traits data at pre-treatment and 18 articles did not present the results of a treatment vs. a control condition. For more information on all included articles, see Table 1. CU=Callous Unemotional traits; DBD= Disruptive Behavior Disorder

Characteristics of included studies

Mean age was 10.04 (SD=3.89), with samples predominantly male (M=74.91%, SD=17.29%) and composed of fewer participants from minority racial/ethnic groups (M=44.19%, SD=29.47%). Location of studies published per 5-year interval is presented in Figure S1. Included studies evaluated treatments with child-focused (66.7%), parenting-focused (55%), pharmacotherapy (23.3%), family-focused (10%), or multiple (43%) components (Table 1; Supplemental Results provides descriptions of each treatment). Included studies were RCTs with no treatment, treatment as usual, or waitlist control conditions (50%), controlled trials without randomization (5%), open trials (42%), or retrospectively-reported treatment outcomes (3%). Nine studies investigated adapted/specialized treatments for CU traits (15%). Finally, studies were rated in quality as high (38%), moderate (22%), low (22%), or very low (18%) (Table S3 and Figure S2).

Table 1.

Summary of the different treatment modalities tested by studies and their inclusion in the meta-analyses.

| Author | Date | Treatment description | Focus of treatment | # of treatment arms | RCT | Meta-analysis aim | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting | Child | Family | Pharmaco-therapy | ||||||

| Hawes & Dadds | 2005 | Parent management training | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Waschbusch et al | 2007 | Summer treatment program +/−methylphenidate | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Norlander | 2008 | Cognitive behavioral therapy | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Kolko et al | 2009 | Multimodal treatment (home or community) | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Caldwell et al | 2012 | Mendota Juvenile Treatment Center | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Dadds et al | 2012 | Family intervention +/− emotion recognition training | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Fung | 2012 | School bullying intervention | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Salekin et al | 2012 | Positive Psychology Intervention | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Somech & Elizur | 2012 | Hitkashrut parenting training | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Blader et al | 2013 | Stimulant medication + parent-focused therapy | 1 | 1 & 2 | |||||

| Frederickson et al | 2013 | Let’s Get Smart | 1 | 1 & 2 | |||||

| Hawes et al | 2013 | Parent management training | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Hogstrom et al | 2013 | Internet-based parent management training | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Hyde et al | 2013 | Family Check-Up | 1 | 1 & 2 | |||||

| Manders et al | 2013 | Multisystemic therapy | 1 | 1 & 2 | |||||

| Masi et al | 2013 | Multimodal therapy | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Reddy et al | 2013 | Cognitive-based compassion training | 1 | 2 | |||||

| White et al | 2013 | Functional family therapy | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Kimonis et al | 2014 | Parent-child interaction therapy | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Kolko et al | 2014 | Multimodal treatment, booster treatment | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Lochman et al | 2014 | Coping Power | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Scott et al | 2014 | Incredible Years | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Hubble et al | 2015 | Emotion recognition training | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Raine et al | 2015 | Omega-3 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Waschbusch et al | 2015 | Behavior education & school intervention | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Byrd | 2016 | Stop-Now-And-Plan | 1 | 1 & 2 | |||||

| Masi et al | 2016 | Multimodal program | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Muratori et al | 2016 | Multimodal program | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Pasalich et al | 2016 | Fast Track | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Raine et al | 2016 | Omega-3 +/− cognitive behavior therapy | 3 | 2 | |||||

| Vanwoerden et al | 2016 | Interpersonal psychodynamic therapy + medication | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Carroll et al | 2017 | KooLKIDS | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Houghton et al | 2017 | KooLKIDS | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Kloft et al | 2017 | Parent management training | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Mattos et al | 2017 | Functional family therapy & cognitive behavioral therapy | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Muratori et al | 2017 | Coping Power or Beyond the Clouds | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Fonagy et al | 2018 | Multisystemic therapy | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Garcia et al | 2018 | Summer treatment program | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Helander et al | 2018 | KOMET (parent management training) +/− Coping Power | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Kjøbli et al | 2018 | Brief parent training or parent management training (Oregon model) or social skills training | 3 | 2 | |||||

| Kyranides et al | 2018 | School-based pilot prevention program | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Masi et al | 2018 | Multimodal program | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Sourander et al | 2018 | Strongest Families telephone-based program | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Bansal et al | 2019 | Summer treatment program | 1 | 1 & 2 | |||||

| Dadds et al | 2019 | Parent management training + emotional engagement or child centered play | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Goertz-Dorten et al | 2019 | Treatment Program for aggressive Behavior | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Kimonis et al | 2019 | Parent-child interaction therapy (CU traits) | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Lui et al | 2019 | Emotion processing skills training | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Pincham, et al | 2019 | Psychosocial intervention | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Raine et al | 2019 | Omega-3 +/− social skills training | 3 | 2 | |||||

| Fleming et al | 2020 | Internet or standard parent-child interaction therapy | 2 | 1 | |||||

| Waschbusch et al | 2020 | Modified & standard summer treatment program | 2 | 1 & 2 | |||||

| da Silva et al | 2021 | PSYCHOPATHY.COMP | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Donohue et al | 2021 | Parent-child interaction therapy (emotion development) | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Raine et al | 2021 | Omega-3 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Thøgersen et al | 2021 | Functional family therapy | 1 | 1 & 2 | |||||

| Bustos | 2022 | Parent Project | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Goertz-Dorten et al | 2022 | Computer-assisted social skills training & supportive resource activation treatment | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Myerberg | 2022 | Coping Power | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Sourander et al | 2022 | Strongest Families Telephone-Based Program | 1 | 2 | |||||

Note. See Table S6 in the Supplemental Materials for more information about included studies

Aim 1: Are treatments equally effective for DBD+CU and DBD-only children?

Overall effect size.

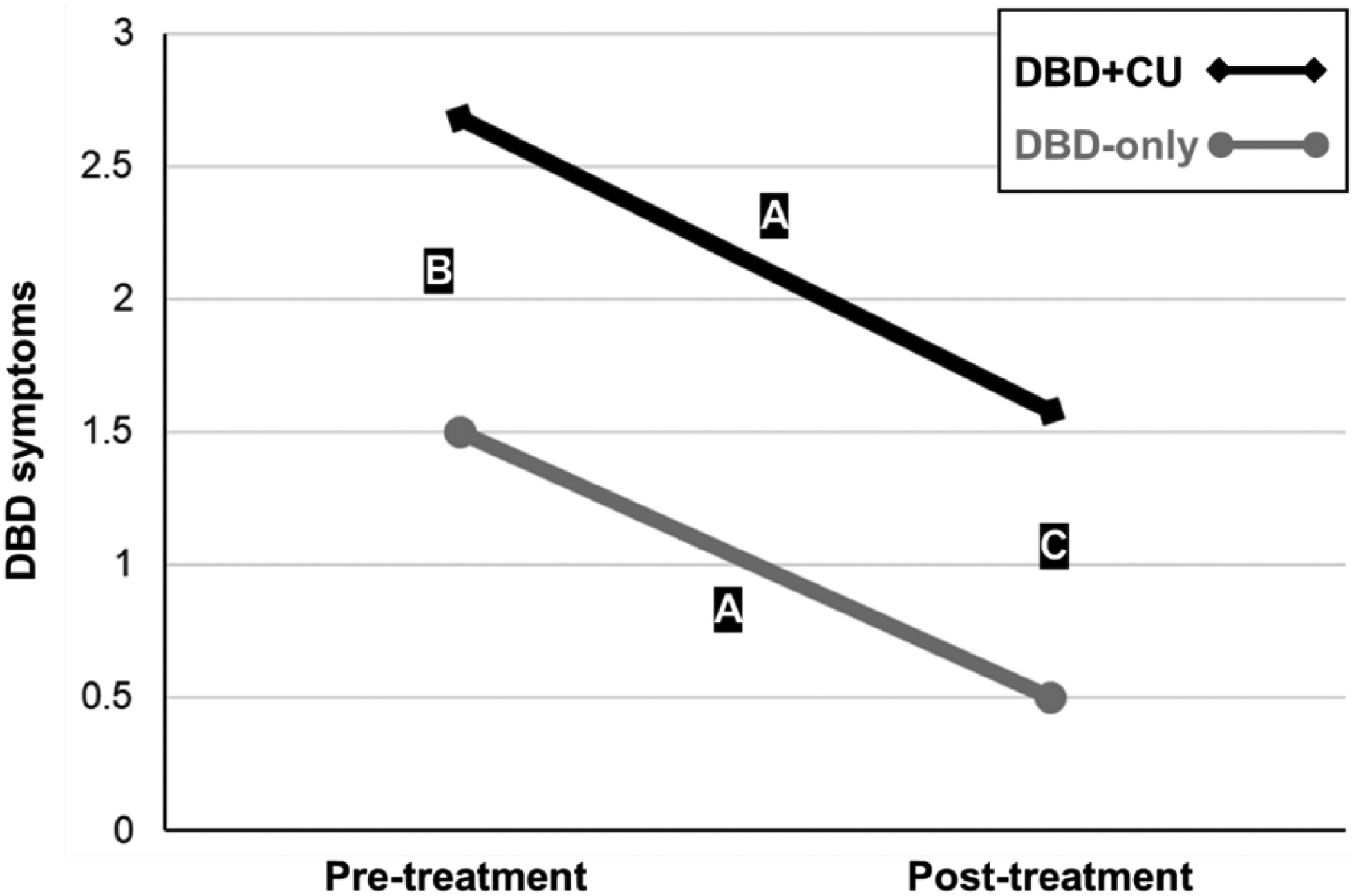

A random-effects multilevel meta-analysis (k=22, 162 effect sizes, 2,465 participants) examined change in DBD symptoms. Overall, DBD symptoms changed significantly pre- to post-treatment (SMD=1.04, p<.01; 95% CI=.42, 1.67) with a four-level model providing the best fit (Supplemental Results). CU traits group was unrelated to treatment outcomes (=−.07, p=.48, 95% CI=−.28, .13; Figure S3), with similar treatment-related reductions in DBD symptoms for DBD+CU (SMD=1.08, p<.001, 95% CI=.45, 1.72) and DBD-only (SMD=1.01, p<.01, 95% CI=.38, 1.64; Figure 2). However, DBD+CU started (k=22; SMD=1.18, p<.001; 95% CI=.57, 1.80) and ended (k=24; SMD=.73, p<.001; 95% CI=.43, 1.04) treatment with more DBD symptoms than DBD-only, which remained significant after controlling for greater pre-treatment severity (=.29, p<.05, 95% CI=.06, .52; Figure S4).

Figure 2.

DBD+CU and DBD-only groups showed similar rates of change in DBD symptoms following treatment but the DBD+CU group started and ended treatment with significantly more DBD symptoms.

Note. The results of three separate multilevel meta-analyses were used to create Figure 1. A. Based on 22 studies, CU traits did not moderate treatment-related change in DBD symptoms (=−.07, p=.48, 95% CI=−.28, .13) with similar reductions for the DBD+CU (SMD=1.08, p<.001, 95% CI= .45, 1.72) and DBD-only (SMD=1.01, p<.01, 95% CI=.38, 1.64) groups. B. Based on 22 studies, the DBD+CU group started treatment with more DBD symptoms than the DBD-only group (SMD=1.18, p<.001; 95% CI=.57, 1.80). C. Based on 24 studies, the DBD+CU group ended treatment with more DBD symptoms than the DBD-only group (SMD=.73, p<.001; 95% CI=.43, 1.04). The greater post-treatment severity in DBD symptoms of the DBD+CU group remained significant after controlling for their greater pre-treatment severity (=.29, p<.05, 95% CI=.06, .52). CU traits=callous-unemotional traits; DBD=disruptive behavior disorder; DBD+CU=group classified as high DBD and high CU traits; DBD-only=group classified as high DBD symptoms and low CU traits; SMD=standard mean difference. CU=callous-unemotional; DBD=disruptive behavior disorder; DBD+CU=group classified as high DBD and high CU traits; DBD-only=group classified as high DBD symptoms and low CU traits; SMD=standard mean difference.

Statistical heterogeneity was due to variance at the study level (93.30%), whereas heterogeneity for the pre-treatment difference (94.56%) and post-treatment difference (88.72%) analyses was due to variance at the treatment level (Supplemental Results). Findings were robust for removing outlying individual effect sizes (Supplemental Results and Figures S5–S6). There was minimal evidence for publication bias based on trim and fill procedures and Egger’s test across the pre-post, pre-treatment differences, and post-treatment differences analyses (Supplemental Results and Figures S7–S8). Finally, results were robust to averaging effect sizes within studies (Supplemental Results and Table S7).

Participant characteristics.

No significant moderators (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overall mean effect size and significant moderators for pre- to post-treatment-related change in DBD symptoms.

| Effect sizes | Model estimates | Overall I2(%) | F(df) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k 4 | k 3 | k 2 | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | |||

| Mean Effect | |||||||||

| Change in DBD symptoms | 22 | 60 | 162 | 1.04** (.42, 1.67) | -- | -- | -- | 98.08 | -- |

| Moderator Variables | |||||||||

| CU traits group (binary) | 22 | 60 | 162 | 1.08*** (.45, 1.72) | −.07 (−.28, .13) | -- | -- | 98.08 | .50 (1, 160) |

| Sample characteristics | |||||||||

| Mean age (continuous) | 22 | 60 | 162 | 1.61* (.02, 3.19) | .07 (−.49, .62) | −.05 (−.20, .10) | −.01 (−.06, .04) | 98.09 | .50 (3, 158) |

| Preschool age (3–5) | 22 | 60 | 162 | 1.06** (.33, 1.79) | −.12 (−.34, .09) | .06 (−1.49, 1.61) | .30 (−.22, .82) | 98.16 | .63 (3, 158) |

| School age (6–12) | 22 | 60 | 162 | .74 (−.15, 1.64) | .04 (−.25, .32) | .68 (−.59, 1.95) | −.22 (−.62, .18) | 98.09 | .82 (3, 158) |

| Adolescent (13–18) | 22 | 60 | 162 | 1.35*** (.61, 2.08) | −.09 (−.35, .16) | −.94 (−2.33, .45) | .06 (−.39, .51) | 98.02 | .76 (3, 158) |

| % Minority (continuous) | 15 | 42 | 128 | 1.31 (−.38, 3.00) | .08 (−.24, .39) | −.004 (−.03, .03) | −.02 (−.01, .004) | 98.64 | .22 (3, 124) |

| % Female (continuous) | 22 | 60 | 162 | 2.02** (.74, 3.30) | −.21 (−.68, .27) | −.03 (−.07, .01) | .004 (−.01, .02) | 97.97 | 1.09 (3, 158) |

| Community sample | 22 | 60 | 162 | 1.14*** (.47, 1.81) | −.02 (−.23, .19) | −.68 (−2.88, 1.51) | −.45 (−1.06, .16) | 98.10 | 1.11 (3, 158) |

| Clinical sample | 22 | 60 | 162 | .47 (−.83, 1.77) | −.28 (−.68, .12) | .79 (−.69, 2.28) | .28 (−.19, .74) | 98.02 | 1.18 (3, 158) |

| Juvenile justice involved | 22 | 60 | 162 | 1.19*** (.50, 1.87) | −.07 (−.29, .15) | −.73 (−2.59, 1.12) | −.04 (−.66, .58) | 98.12 | .39 (3, 158) |

| Treatment characteristics | |||||||||

| Parenting-focused component (binary) | 22 | 60 | 162 | .55 (−.34, 1.45) | −.12 (−.40, .16) | .97 (−.25, 2.19) | .09 (−.32, .50) | 97.92 | 1.17 (3, 158) |

| Child-focused component (binary) | 22 | 60 | 162 | .79* (.07, 1.52) | .17 (−.15, .49) | .50 (−.03, 1.03) | −.38 (−.78, .02) | 98.24 | 1.78 (3, 158) |

| Family-focused component (binary) | 22 | 60 | 162 | 1.31*** (.66, 1.95) | −.15 (−.38, .08) | −1.05** (−1.79, −.30) | .32 (−.18, .81) | 98.03 | 2.74* (3, 158) |

| Pharmacotherapy (binary) | 22 | 60 | 162 | .85** (.27, 1.42) | −.10 (−.33, .12) | 2.65** (.75, 4.55) | .24 (−.38, .85) | 97.45 | 3.21* (3, 158) |

| Multimodal (binary) | 22 | 60 | 162 | .83* (.17, 1.50) | .01 (−.26, .29) | .59* (.05, 1.14) | −.19 (−.60, .22) | 98.06 | 1.71 (3, 158) |

| CU traits targeted (binary) | 22 | 60 | 162 | 1.08** (.44, 1.72) | −.05 (−.27, .17) | .09 (−.72, .90) | −.25 (−.99, .50) | 98.10 | .31 (3, 158) |

| Weekly vs. more frequent (binary) | 22 | 60 | 162 | 1.23* (.22, 2.24) | −.06 (−.37, .24) | −.24 (−1.55, 1.07) | −.02 (−.44, .40) | 98.16 | .22 (3, 158) |

| Duration in weeks (continuous) | 22 | 60 | 162 | .94 (−.14, 2.02) | .07 (−.25, .39) | .01 (−.05, .07) | −.01 (−.03, .01) | 98.17 | .58 (3, 158) |

| Study characteristics | |||||||||

| RCT | 22 | 60 | 162 | 1.14** (.35, 1.92) | −.07 (−.32, .19) | −.16 (−1.55, 1.22) | −.02 (−.46, .41) | 98.17 | .19 (3, 158) |

| USA | 22 | 60 | 162 | .89 (−.02, 1.79) | −.11 (−.40, .19) | .40 (−.89, 1.68) | .07 (−.34, .48) | 98.13 | .36 (3, 158) |

| Parent-Report | 22 | 60 | 162 | .94** (.31, 1.58) | −.05 (−.30, .21) | .24 (−.003, .47) | −.05 (−.32, .23) | 97.98 | 2.26 (3, 158) |

| Child-Report | 22 | 60 | 162 | 1.16*** (.53, 1.78) | −.12 (−.34, .09) | −.44*** (−.70, −.18) | .25 (−.06, .55) | 98.02 | 4.68** (3, 158) |

| Teacher-Report | 22 | 60 | 162 | .98** (.33, 1.64) | .01 (−.22, .24) | .49 (−.02, 1.00) | −.38 (−.83, .07) | 98.16 | 1.54 (3, 158) |

| Follow-Up Only | 22 | 60 | 162 | 1.15** (.39, 1.91) | −.11 (−.34, .12) | −.26 (−1.72, 1.20) | .17 (−.31, .65) | 98.17 | .35 (3, 158) |

| Year (continuous) | 22 | 60 | 162 | 2.20 (−1.23, 5.62) | 1.03* (.04, 2.01) | −.07 (−.28, .14) | −.07* (−.13, −.01) | 98.07 | 2.18 (3, 158) |

| Quality (continuous) | 22 | 60 | 162 | .27 (−1.28, 1.81) | −.26 (−.75, .23) | .30 (−.23, .83) | .07 (−.10, .24) | 98.03 | .96 (3, 158) |

Note.

p<.05*,

p<.01**,

p<.001***.

represents the effect size for the intercept (i.e., the SMD) for a specific value of the moderator; and represents the represents change in the pooled effect when the moderating variable increases. (95% CI) represents the interaction of and . CU=Callous-unemotional; SMD= Standard Mean Difference; RCT=randomized controlled trial; US=United States

Treatment characteristics.

No significant moderators (Table 2).

Study characteristics.

Year of publication moderated the association between CU traits group and change in DBD symptoms (=−.07, p<.05; 95% CI=−.13, −.01, Table 2), but was unrelated to outcomes when DBD+CU (p=.53) and DBD-only (p=.18) were examined separately. No other study characteristics were significant moderators (Table 2).

Study Aim 2: Do DBD treatments directly reduce CU traits?

Overall effect size.

A random-effects multilevel meta-analysis of controlled studies (k=25, 51 effect sizes; 5,646 participants) examined change in CU traits. Overall, treatment was not associated with reductions in CU traits (SMD=.09, p=.10, 95% CI=−.02, .20; Figure S9), with a three-level model providing the best fit (Supplemental Results). Statistical heterogeneity was due to variance at the treatment level (72.23%) (Supplemental Results). Findings were robust to the removal of outliers for individual effect sizes (Figure S10). Although Egger’s test results suggested minimal publication bias, studies were missing from the right side of the funnel plot (Figure S11). Results were robust when we averaged effect sizes within studies (Table S7).

Participant characteristics.

Sample racial/ethnic composition was related to treatment-related reductions in CU traits (=−.01, p<.001, 95% CI=−.01, −.003, Table 3), which were significant when less than half of the sample was from a racial/ethnic minority (k=18, SMD=.15, p<.05, 95% CI=.002, .30), but not when more than half of the sample was from a racial/ethnic minority (k=11, SMD=−.13, p=.19, 95% CI=−.32, .06). The effect of sample racial/ethnic composition remained significant after controlling for age, sample type, location, and study quality (see Supplemental Results). No other participant characteristics were moderators (Table 3).

Table 3.

Overall mean effect size and significant moderators for the effect of treatment versus a control condition on CU traits.

| Effect sizes | Model estimates | Overall I2(%) | F(df) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k 3 | k 2 | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | |||

| Mean Effect | ||||||

| CU traits | 34 | 51 | .09 (−.02, .20) | 74.94 | ||

| Moderator Variables | ||||||

| Sample characteristics | ||||||

| Mean age (continuous) | 34 | 51 | .38* (.07, .69) | −.03 (−.06, .000) | 73.52 | 3.99 (1, 49) |

| Preschool age (binary) | 34 | 51 | .04 (−.08, .16) | .27 (−.004, .55) | 73.48 | 3.92 (1, 49) |

| School age (binary) | 34 | 51 | .17, (−.003, .35) | −.13 (−.37, .09) | 74.53 | 1.39 (1, 49) |

| Adolescent (binary) | 34 | 51 | .11 (−.02, .23) | −.06 (−.33, 21) | 75.75 | .19 (1, 49) |

| Percentage minority (continuous) | 28 | 43 | .34*** (.15, .52) | −.01*** (−.01, .003) | 64.12 | 14.24*** (1, 41) |

| Percentage female (continuous) | 34 | 51 | .21 (−.02, .45) | −.004 (−.01, .003) | 74.54 | 1.33 (1, 49) |

| Community sample (binary) | 34 | 51 | .07 (−.05, .20) | .08 (−.19, 35) | 75.48 | .37 (1, 49) |

| Clinical sample (binary) | 34 | 51 | .09 (−.11, .29) | .005 (0.24, .25) | 75.78 | .002 (1, 49) |

| Juvenile justice involved (binary) | 34 | 51 | .11 (−.01, .23) | −.12 (−.45, .21) | 75.58 | .54 (1, 49) |

| Treatment characteristics | ||||||

| Parenting-focused component (binary) | 34 | 51 | −.02 (−.17, .13) | .22* (.01, .44) | 72.64 | 4.47* (1, 49) |

| Child-focused component (binary) | 34 | 51 | .14 (−.04, .31) | −.07 (−.30, .16) | 75.59 | .41 (1, 49) |

| Family-focused component (binary) | 34 | 51 | .09 (−.03, .21) | .06 (−.39, .50) | 75.81 | .07 (1, 49) |

| Pharmacotherapy (binary) | 34 | 51 | .15* (.03, .28) | −.23 (−.47, .02) | 72.85 | 3.52 (1, 49) |

| Multimodal (binary) | 34 | 51 | .07 (−.06, .21) | .06 (−.19, .31) | 75.54 | .26 (1, 49) |

| CU traits targeted (binary) | 34 | 51 | .04 (−.37, .45) | .06 (−.37, .49) | 75.73 | .07 (1, 49) |

| Weekly vs. more frequent (binary) | 34 | 51 | .05 (−.13, .22) | .08 (−.15, .31) | 76.24 | .46 (1, 49) |

| Duration in weeks (continuous) | 34 | 51 | .09 (−.04, 23) | −.000 (−.002, .002) | 75.91 | .000 (1, 49) |

| Study Characteristics | ||||||

| RCT (binary) | 34 | 51 | .32 (−.01, .65) | −.25 (−.60, .09) | 73.95 | 2.18 (1, 49) |

| US (binary) | 34 | 51 | .19** (.05, .32) | −.24* (−.46, −.03) | 71.45 | 5.30* (1, 49) |

| Parent-reported measure of CU traits (binary) | 34 | 51 | −.001 (−.13, .13) | .16* (.03, .29) | 72.79 | 6.53* (1, 49) |

| Child-reported measure of CU traits (binary) | 34 | 51 | .14* (.02, .25) | −.15* (−.29, −.02) | 73.24 | 5.26 (1, 49) |

| Teacher-reported measure of CU traits (binary) | 34 | 51 | .11 (−.01, .22) | −.12 (−.43, .18) | 75.4 | .65 (1, 49) |

| Measure of CU Traits: APSD (binary) | 34 | 51 | .20** (.06, .35) | −.21* (−.41, −.02) | 70.81 | 4.75* (1, 49) |

| Measure of CU Traits: ICU (binary) | 34 | 51 | .05 (−.08, .17) | .15 (−.07, .37) | 73.29 | 1.91 (1, 49) |

| Measure of CU Traits: YPI (binary) | 34 | 51 | .09 (−.02, .20) | .18 (−.33, .70) | 74.68 | .50 (1, 49) |

| Immediate vs. long-term follow-up (binary) | 34 | 51 | .10 (−.03, .23) | −.03 (−.30, .24) | 75.95 | .06 (1, 49) |

| Year published (continuous) | 34 | 51 | −.24 (−.89, .41) | .02 (−.02, .06) | 74.99 | 1.09 (1, 49) |

| Study quality (continuous) | 34 | 51 | −.38 (−.75, .001) | .15* (.03, .26) | 71.15 | 6.75* (1, 49) |

Note.

p<.05*,

p<.01**,

p<.001***.

APSD= Antisocial Process Screening Device; CU=Callous-unemotional; ICU= Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits; SMD= Standard Mean Difference; RCT=randomized controlled trial; US=United States; YPI= Youth Psychopathic Traits Inventory

Treatment characteristics.

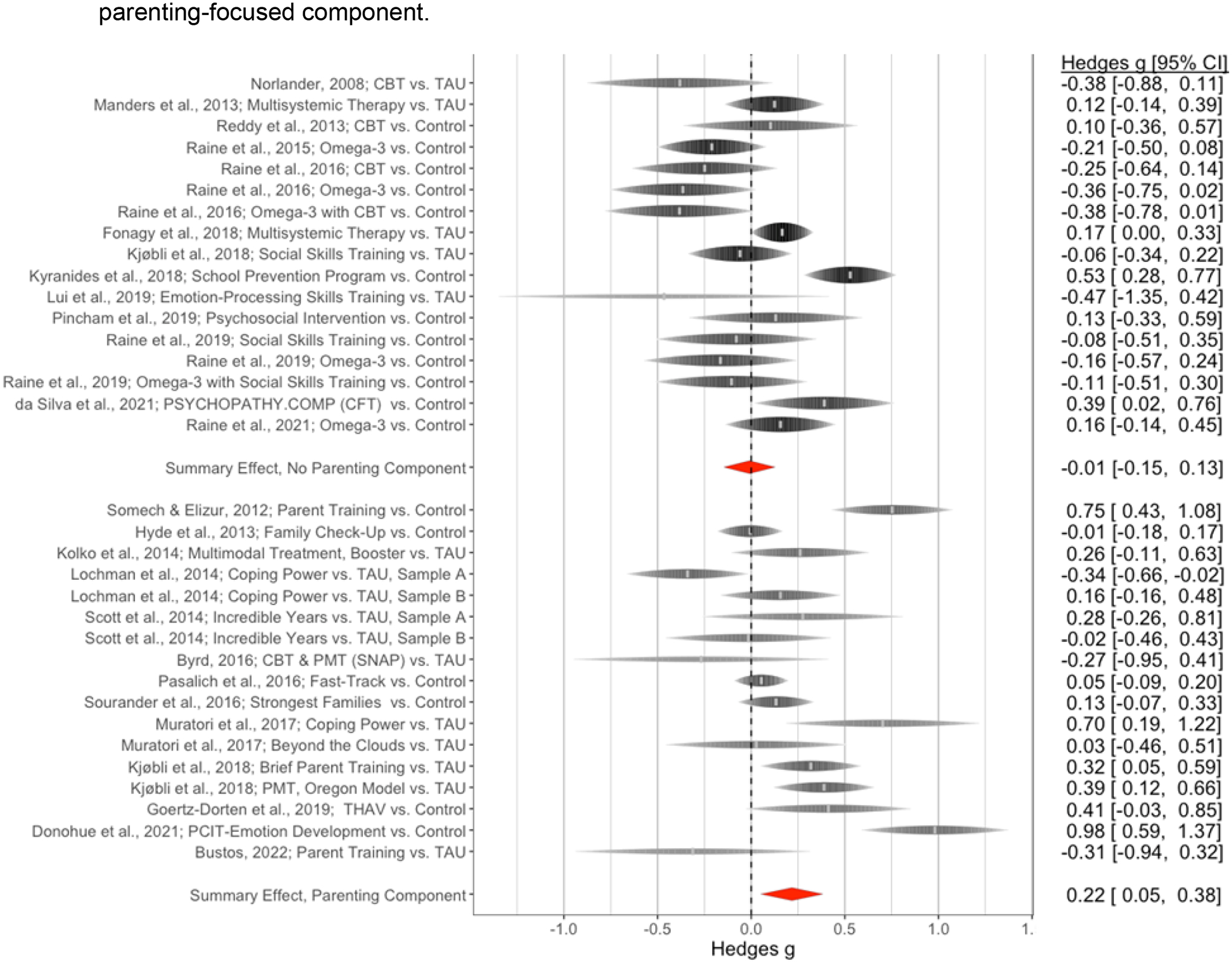

Treatment type was related to reductions in CU traits (=.22, p<.05, 95% CI=.01, .44; Table 3), with significant reductions for treatments with a parenting-focused component (k=17, SMD=.22, p<.05, 95% CI=.06, .38; Figure 3). Effects were robust to averaging effect sizes within studies and including age as a covariate, but not controlling for study quality or use of parent-reported measures of CU traits (Supplemental Results). No other treatment characteristics were moderators (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plots show a significant treatment effect on CU traits only for studies with a parenting-focused component.

Study characteristics.

First, study quality was related to treatment reductions in CU traits (=.15, p<.05, 95% CI=.03, .26; Figure S12, Table 3), with significant reductions only for studies rated as high quality (k=15, SMD=.26, p<.001, 95% CI=.13, .39; Table 3). Second, informant was related to treatment outcomes (=.16, p<.05, 95% CI= .03, .29, Table 3), with significant reductions for parent-reported (k=22, SMD=.16, p<.01, 95% CI=.04, .28), but not child-reported (k=16; SMD=−.02, p=.85, 95% CI=−.16, .13) or teacher-reported (k=5; SMD=−.02, p=.92, 95% CI= −31, .28) measures of CU traits. The effect of parent-reported measures was robust to controlling for age and use of parenting-focused treatments, but became non-significant when models controlled for study quality (see Supplemental Results).

Third, location was related to treatment effects on CU traits (=−.24, p<.05, 95% CI=−.46, −.03, Table 3), with significant reductions in CU traits reported by studies conducted outside the US (k=20; SMD=.19, p<.01, 95% CI=.05, .32) but not within the US (k=14; SMD=−.06, p=.49, 95% CI=−.22, .11). However, studies conducted in the US had samples with more participants from a racial/ethnic minority (r=.46, p<.01), with the effect of location on treatment-related reductions in CU traits rendered non-significant after controlling for sample racial/ethnic composition (see Supplemental Results).

Finally, use of the APSD was related to outcomes (=−.21, p<.05, 95% CI= −.41, −.02, Table 3), with no treatment effects among studies using the APSD (k=19, SMD=−.01, p=.90, 95% CI=−.17, .15) but significant treatment-related reductions in CU traits among studies that did not use the APSD (e.g., k=17, SMD=.22, p<.01, 95% CI=.08, .36). Older studies (r=−.36, p<.05) and studies conducted in the US (X2= 4.85, p<.05) were more likely to have used the APSD (see Supplemental Results), with the effect of APSD on treatment outcomes remaining significant after controlling for sample age but not after controlling for publication year, location, or study quality (see Supplemental Results). No other study characteristics were significant moderators (Table 3).

Post-hoc analysis of pre-post treatment studies.

A random-effects multilevel meta-regression model (k=40, 76 effect sizes, 4,733 participants) examining pre- to post-treatment changes in CU traits among studies that had used controlled or uncontrolled study designs revealed that CU traits changed significantly pre- to post-treatment (SMD=.42, p<.001, 95% CI=.24, .60; Figure S13), with a four-level model providing the best fit (see Supplemental Results and Figures S14–15).

Discussion

We addressed two questions about the effectiveness of DBD treatments. First, we evaluated evidence for differential treatment effects on DBD symptoms for DBD+CU versus DBD-only. In a multi-level analysis of 22 studies with pre- and post-treatment outcomes, we provide evidence that DBD+CU and DBD-only children show comparable rates of symptom reduction following treatment, refuting the notion that DBD+CU confers treatment resistance. However, a separate multi-level analysis of 24 studies confirmed that DBD+CU children start and end treatment with more DBD symptoms when compared to DBD-only children, supporting clinical observations that the DBD+CU designation signifies greater severity and therapeutic need. Second, we evaluated direct effects of DBD treatments on CU traits. A multi-level meta-analysis of 25 controlled studies demonstrated no overall treatment-related reductions in CU traits. However, moderation analysis pointed to significant reductions in CU traits when treatments had a parenting-focused component, in studies conducted outside the US, when less than half of the sample was from a racial/ethnic minority, when the measure of CU traits was not the APSD, for parent-reported measures of CU traits, and for studies rated as higher in quality.

There are several clinical implications of these findings. First, the finding that DBD+CU and DBD-only children showed comparable rates of symptom reduction following treatment implies that existing child-focused, parenting-focused, pharmacotherapeutic, and multimodal approaches can remain first line treatments for DBD, even when children have CU traits (Fairchild et al., 2019; Frick et al., 2014). Moreover, we found minimal evidence that participant (e.g., age, type) or treatment (e.g., modality, length) characteristics moderated the comparable reduction in symptoms found for DBD+CU and DBD-only. This implication is important in the context of prior beliefs about the “un-treatability” of DBD+CU, suggesting that established, evidence-based treatments for DBD can bring about reductions in DBD symptoms even among children with CU traits. Moreover, since access to novel or adapted treatments remains limited or unavailable to most families, our findings are encouraging in establishing that existing DBD treatments continue to hold benefit for children with CU traits.

Second, we showed that treatments with a parenting-focused component were effective in directly reducing CU traits. This finding echoes prior reviews that have emphasized the role of parenting in the development and treatment of CU traits (Hawes et al., 2014; Waller et al., 2013; Wilkinson et al., 2016), as well as the role of parental involvement in ameliorating DBD symptoms more broadly (McMahon et al., 2021). The most effective content for parenting programs for DBD includes behavior management (e.g., praise, ignore undesired behavior) and self-management (e.g., emotion regulation, problem-solving) techniques (Leijten et al., 2022), which should remain the cornerstone of parenting programs for DBD+CU. Observational studies have also emphasized the role of parental warmth in developmental pathways to CU traits (Waller & Hyde, 2018; Waller et al., 2018), with preliminary evidence that treatments that directly increase parental warmth (e.g., affection, praise, play) or target parental attributions and positive feelings about their child may be particularly effective for DBD+CU children (Piotrowska et al., 2017; Sawrikar & Dadds, 2018; Sawrikar et al., 2018). Consistent with prior meta-analytic evidence (Gardner et al., 2019), the effect of parenting-focused treatments on CU traits remained significant after controlling for sample age, and treatment type did not interact with age. Thus, our findings imply that treatments with a parenting component, including those targeting parental warmth or positive attributions, can help to reduce CU traits across different ages.

Third, the post-treatment difference in DBD symptom severity for DBD+CU children was attenuated, but not diminished, after accounting for pre-treatment differences in severity. That is, the fact that DBD+CU children started treatment with greater DBD symptom severity did not fully explain why they ended treatment with more symptoms than DBD-only children. When taken in conjunction with the other findings, one implication is that we could test fully adapted and stand-alone treatments for DBD+CU versus DBD-only children (Hyde et al., 2014). Here, the theory of change would be that current and/or standard DBD treatments do not adequately target the distinct etiological factors involved in DBD+CU. An alternative, but not mutually exclusive, implication is that we need adjunctive modules paired with traditional treatments that are used as “add-ons” when children have high CU traits, which might comprise more child-focused components. Here, the theory of change is that standard DBD treatments work to some degree in reducing DBD symptoms for DBD+CU, as suggested by our findings for our first study aim, but adjunctive modules are needed to target the specific socioemotional and interpersonal difficulties associated with CU traits. Directly targeting CU traits through adjunctive modules could lead to further reductions in DBD symptoms, thus bringing DBD+CU children in line with their DBD-only peers, although this possibility (i.e., reductions in CU traits as a mediator of change in DBD symptoms) has not been tested formally.

By including moderation analyses in both aims of whether studies evaluated treatment modules designed to target CU traits, our multi-level meta-analytic approach afforded a preliminary test of these questions. We found no evidence for moderation, with similar effects for adapted versus traditional treatments, including for treatment effects for DBD+CU versus DBD-only or direct treatment effects on CU traits. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution. Only three of 24 studies tested an adapted treatment comparing DBD+CU versus DBD-only children. Likewise, only three of 25 controlled studies tested adapted treatments for directly reducing CU traits, with randomization in only 2 of those 3. Finally, only eight of 40 controlled or uncontrolled studies investigating pre-post treatment effects on CU traits tested an adapted treatment. Across all aims, three adapted treatments had parenting-focused components, five had child-focused components, and one had both. Finally, of those 9 studies, 4 recruited juvenile-justice involved adolescents with greater symptom severity, which could have reduced the likelihood of detecting differential rates of symptom reduction in adapted versus traditional treatments.

Taken together, our findings highlight several clinical research priorities. First, more research is needed to develop and test multiple adapted treatments for DBD+CU and/or CU traits across a range of ages and sample types. Relatedly, nearly half of included studies were rated low/very low in quality, with only studies rated as “high quality” reporting treatment-related reductions in CU traits. Thus, we urgently need to evaluate treatments for DBD+CU and/or CU traits using high-quality RCT designs. Such designs could facilitate a direct test of different theories of change within the field, comparing the effectiveness of fully adapted DBD treatments for DBD+CU children or adjunctive modules that are added to traditional DBD treatments to target CU traits. The Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (UP) represents a useful heuristic for addressing these questions in relation to the treatment of DBD+CU. The UP is a transdiagnostic and emotion-focused form of cognitive-behavioral therapy that is universally implemented for anxiety and unipolar mood disorders, but with embedded flexibility for adding or skipping modules based on individual-level traits (Carlucci et al., 2021; Farchione et al., 2012). Use of RCT and/or sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART) (Hampton & Chow, 2022) designs would allow for directly testing the effectiveness of different combinations and/or temporal sequences of universal versus specialized modules for DBD+CU versus DBD-only and for exploring potential mechanisms and moderators of treatment.

Second, we found treatment-related reductions in CU traits based only on parent report. This finding could reflect treatment participation rather than actual clinical improvement (Reyno & McGrath, 2006). However, change in parental perceptions of child behavior could also reflect an important marker of improvement, especially for parenting-focused treatments (Sawrikar et al., 2018). This assertion is supported by evidence that parents of DBD+CU children report more negative attributions about their child’s behavior (Palm et al., 2019; Sawrikar & Dadds, 2018). Thus, directly addressing parental attributions about their child may be a critical future target of treatments for DBD+CU. At the same time, fewer effect sizes were derived from child (37%) and teacher (10%) reports. Future research is therefore needed to establish who best to report on clinical changes in CU traits, with some evidence for differential informant effects on ratings of CU traits contingent on age (Matlasz et al., 2021). Future studies could leverage multi-informant measures, an approach successfully employed within treatment studies for childhood anxiety (Norris et al., 2019) and autism spectrum disorder (van den Berk-Smeekens et al., 2021).

Third, we found non-significant treatment effects on CU traits when studies used the APSD, which remained significant after accounting for sample age but not publication year, study quality, or study location. Notably, older studies and studies conducted within the US were more likely to have administered the APSD, with more recent studies perhaps reacting to noted limitations of the APSD, including low reliability and limited variance of the CU traits scale (Kotler & McMahon, 2010). Nevertheless, the differential treatment effects found on the basis of measure highlight the need for reliable measures of CU traits with standardized norming procedures and established clinical cut-offs. This point is exemplified by the range of categorization methods (e.g., mean/median split, 90th percentile, +/− 1 SD around mean) used by studies to define DBD+CU versus DBD-only groups, with only 37% using a clinically-informed approach, which likely related to the significant variance we found at the study level. Recent efforts have begun to test clinical cut-offs for the parent-, teacher- and self-reported ICU (Kemp et al., 2021; Pueyo et al., 2022) and validate clinical interviews for CU traits (Hawes et al., 2020). However, without established cut-offs, we lack the ability to reliably identify DBD+CU versus DBD-CU children or establish meaningful normalization of CU traits following treatment. A critical research priority therefore relates to the need for consistently-applied age and sex-based norms for measures of CU traits, established within large population-based studies of children.

Finally, there were reported treatment effects on CU traits only for studies conducted outside the US (although location did not moderate treatment-related differences in DBD symptoms, suggestive of some specificity for CU traits). The effect of location remained significant after accounting for measure, which is pertinent since studies conducted in the US more commonly used the APSD. However, the effect of location was rendered non-significant when accounting for racial/ethnic composition of samples, with studies conducted in the US more likely to have included a higher percentage of racial/ethnic minority participants. That is, the effect of location appeared to be driven by greater racial/ethnic minority sample composition in US-based studies. These findings reinforce calls to develop culturally-informed DBD treatments and measures of CU traits (Johnson et al., 2018; Taylor & Ray, 2021), as well as to address racism experienced by historically marginalized racial/ethnic groups within healthcare settings (Mateo & Williams, 2021), which impacts diagnosis, conceptualization of risk factors, and treatments for DBD (Fadus et al., 2020; Menand & Cox, 2022).

Our findings should be considered alongside several limitations. First, given the paucity of RCT studies, we included open trial and other uncontrolled study designs (Table S8). Although quality was covaried within models, caution is needed when interpreting the results, which may overestimate true effect sizes. Second, we included varying treatment approaches, which was reflected in significant heterogeneity between studies at the treatment level. Future empirical and meta-analytic work evaluating narrowly-defined treatment components for CU traits is warranted. Third, included studies addressing our first aim had to examine differences in DBD outcomes by a group-based definition of CU traits (i.e., high/low, present/absent), leading to the exclusion of potentially relevant studies. Fourth, few studies evaluated treatment gains beyond initial post-treatment effects. Thus, future efforts need assessments with longer follow-up periods and of more distal outcomes, including employment status, educational attainment, and physical health. Finally, our pre-registered analytic plan was not fully executed due to limited data on compliance, adherence, clinical samples, and adverse outcomes (see Supporting Information).

In sum, while DBD+CU children are responsive to treatment, CU traits are associated with greater post-treatment symptom severity. In addition, programs with a parenting component appeared effective in directly reducing CU traits. In the next generation of treatments for DBD, we urgently need prevention and treatment efforts that begin early in life when behavior problems emerge and the development of empathy and prosociality can go awry (i.e., foreshadowing CU traits) (Waller & Hyde, 2018). To realize these efforts, funding allocation for DBD research and treatment, which lags behind that for other childhood psychiatric disorders (Rees et al., 2021), must be increased. Pediatric care should prioritize treatment access for children with DBD symptoms and/or CU traits, supported by the validation of screening tools for CU traits that allow specialized treatment modules to be targeted at different ages, akin to screenings for autism spectrum disorder that begin early in life (Allison et al., 2012). Universal parent training programs offered as preventative interventions for all families could have widespread benefits to child mental health and development (Sanders & Mazzucchelli, 2022). Such investments would be cost-effective and warranted from a public health perspective when weighed against the staggering financial costs incurred by the consequences of DBD+CU, including violence, crime, and incarceration (Bachmann et al., 2022).

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

It is unknown if treatments for disruptive behavior disorders are as effective for children with callous-unemotional traits (DBD+CU) as those without (DBD-only), nor if treatments directly reduce callous-unemotional traits.

In multilevel meta-analyses combining 60 studies, there were similar treatment-related reductions in DBD symptoms for DBD+CU and DBD-only children, although DBD+CU started and ended treatment with more DBD symptoms.

Treatments with a parenting-focused component were associated with reductions in callous-unemotional traits.

Treatments for disruptive behavior disorders, particularly those targeting parenting, are effective for children with callous-unemotional traits, but personalized adjunctive treatment modules are warranted to bring about greater improvement in this higher-risk group.

Acknowledgements

The preparation of this manuscript was partially supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH125904, R21 MH126162) and institutional funding from the University of Pennsylvania. The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article:

References

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms and profiles (Vol. 30). Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research center for children, youth …. [Google Scholar]

- Allison C, Auyeung B, & Baron-Cohen S (2012). Toward brief “red flags” for autism screening: the short autism spectrum quotient and the short quantitative checklist in 1,000 cases and 3,000 controls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(2), 202–212. e207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andershed H, Gustafson SB, Kerr M, & Stattin H (2002). The usefulness of self‐reported psychopathy‐like traits in the study of antisocial behaviour among non‐referred adolescents. European Journal of Personality, 16(5), 383–402. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade C (2020). Mean difference, standardized mean difference (SMD), and their use in meta-analysis: as simple as it gets. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 81(5), 11349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann CJ, Beecham J, O’Connor TG, Briskman J, & Scott S (2022). A good investment: Longer‐term cost savings of sensitive parenting in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(1), 78–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balia C, Carucci S, Coghill D, & Zuddas A (2018). The pharmacological treatment of aggression in children and adolescents with conduct disorder. Do callous—unemotional traits modulate the efficacy of medication? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 91, 218–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Meerpohl J, & Norris S (2011). GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 64(4), 401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlucci L, Saggino A, & Balsamo M (2021). On the efficacy of the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review, 87, 101999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung MW-L (2019). A guide to conducting a meta-analysis with non-independent effect sizes. Neuropsychology review, 29(4), 387–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, Allen JL, McGregor K, Woolgar M, Viding E, & Scott S (2014). Callous‐unemotional traits in children and mechanisms of impaired eye contact during expressions of love: A treatment target? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(7), 771–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Brito SA, Forth AE, Baskin-Sommers AR, Brazil IA, Kimonis ER, Pardini D, Frick PJ, Blair RJR, & Viding E (2021). Psychopathy. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 7(1), 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekkers TJ, Hornstra R, Van der Oord S, Luman M, Hoekstra PJ, Groenman AP, & van den Hoofdakker BJ (2022). Meta-analysis: Which Components of Parent Training Work for Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 61(4), 478–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drugli MB, Larsson B, Fossum S, & Mørch WT (2010). Five‐to six‐year outcome and its prediction for children with ODD/CD treated with parent training. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(5), 559–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval S, & Tweedie R (2000). Trim and fill: a simple funnel‐plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta‐analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, & Minder C (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj, 315(7109), 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadus MC, Ginsburg KR, Sobowale K, Halliday-Boykins CA, Bryant BE, Gray KM, & Squeglia LM (2020). Unconscious bias and the diagnosis of disruptive behavior disorders and ADHD in African American and Hispanic youth. Academic Psychiatry, 44(1), 95–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild G, Hawes DJ, Frick PJ, Copeland WE, Odgers CL, Franke B, Freitag CM, & De Brito SA (2019). Conduct disorder. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 5(1), 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farchione TJ, Fairholme CP, Ellard KK, Boisseau CL, Thompson-Hollands J, Carl JR, Gallagher MW, & Barlow DH (2012). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Behavior therapy, 43(3), 666–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Castilla B, Jamshidi L, Declercq L, Beretvas SN, Onghena P, & Van den Noortgate W (2020). The application of meta-analytic (multi-level) models with multiple random effects: A systematic review. Behavior Research Methods, 52(5), 2031–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ (2004). Inventory of callous–unemotional traits. Unpublished rating scale. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Frick PJ, & Hare RD (2001). Antisocial Process Screening Device. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Ray JV, Thornton LC, & Kahn RE (2014). Annual research review: A developmental psychopathology approach to understanding callous‐unemotional traits in children and adolescents with serious conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(6), 532–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F, Leijten P, Melendez‐Torres G, Landau S, Harris V, Mann J, Beecham J, Hutchings J, & Scott S (2019). The earlier the better? Individual participant data and traditional meta‐analysis of age effects of parenting interventions. Child Development, 90(1), 7–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton LH, & Chow JC (2022). Deeply tailoring adaptive interventions: Enhancing knowledge generation of SMARTs in special education. Remedial and Special Education, 43(3), 195–205. [Google Scholar]

- Harris GT, & Rice ME (2006). Treatment of Psychopathy: A Review of Empirical Findings.

- Hawes DJ, Kimonis ER, Mendoza Diaz A, Frick PJ, & Dadds MR (2020). The Clinical Assessment of Prosocial Emotions (CAPE 1.1): A multi-informant validation study. Psychological Assessment, 32(4), 348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes DJ, Price MJ, & Dadds MR (2014). Callous-unemotional traits and the treatment of conduct problems in childhood and adolescence: A comprehensive review. Clinical child and family psychology review, 17(3), 248–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes SW, Byrd AL, Waller R, Lynam DR, & Pardini DA (2017). Late childhood interpersonal callousness and conduct problem trajectories interact to predict adult psychopathy. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(1), 55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herpers PC, Scheepers FE, Bons DM, Buitelaar JK, & Rommelse NN (2014). The cognitive and neural correlates of psychopathy and especially callous–unemotional traits in youths: A systematic review of the evidence. Development and Psychopathology, 26(1), 245–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hukkelberg S, Ogden T, & Thøgersen DM (2022). Youth Level of Service/Case Management Inventory Assessments as Predictors of Behavioral Change in Multisystemic Therapy and Functional Family Therapy in Norway. Research on Social Work Practice, 10497315221086641. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde LW, Waller R, & Burt SA (2014). Commentary: Improving treatment for youth with callous‐unemotional traits through the intersection of basic and applied science–reflections on Dadds et al.(2014). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(7), 781–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AD, Anhalt K, & Cowan RJ (2018). Culturally responsive school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports: A practical approach to addressing disciplinary disproportionality with African-American students. Multicultural Learning and Teaching, 13(2). [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE (1997). Parent management training: Evidence, outcomes, and issues. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(10), 1349–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp EC, Frick PJ, Matlasz TM, Clark JE, Robertson EL, Ray JV, Thornton LC, Wall Myers TD, Steinberg L, & Cauffman E (2021). Developing cutoff scores for the inventory of callous-unemotional traits (ICU) in justice-involved and community samples. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Down J, Aouira N, Bor W, Haywood A, Littlewood R, Heussler H, & McDermott B (2019). Current pharmacotherapy options for conduct disorders in adolescents and children. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy, 20(5), 571–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimonis ER, Fleming G, Briggs N, Brouwer-French L, Frick PJ, Hawes DJ, Bagner DM, Thomas R, & Dadds M (2019). Parent-child interaction therapy adapted for preschoolers with callous-unemotional traits: An open trial pilot study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(sup1), S347–S361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantopoulos S (2011). Fixed effects and variance components estimation in three‐level meta‐analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 2(1), 61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotler JS, & McMahon RJ (2010). Assessment of child and adolescent psychopathy. Handbook of child and adolescent psychopathy, 79–109. [Google Scholar]

- Leijten P, Melendez‐Torres G, & Gardner F (2022). Research Review: The most effective parenting program content for disruptive child behavior–a network meta‐analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(2), 132–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell JH, Pigott TD, Nilsen KH, Green SJ, & Montgomery OL (2021). Multisystemic Therapy® for social, emotional, and behavioural problems in youth age 10 to 17: An updated systematic review and meta‐analysis. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 17(4), e1158. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo CM, & Williams DR (2021). Racism: a fundamental driver of racial disparities in health-care quality. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 7(1), 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matlasz TM, Frick PJ, & Clark JE (2021). A Comparison of Parent, Teacher, and Youth Ratings on the Inventory of Callous–Unemotional Traits. Assessment, 10731911211047893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Goulter N, & Frick PJ (2021). Moderators of psychosocial intervention response for children and adolescents with conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 50(4), 525–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Witkiewitz K, & Kotler JS (2010). Predictive validity of callous–unemotional traits measured in early adolescence with respect to multiple antisocial outcomes. Journal of abnormal psychology, 119(4), 752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menand E, & Cox LJ (2022). The overlap between trauma & disruptive behavior disorders. In Not Just Bad Kids (pp. 251–289). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Nakamura EF, & Kessler RC (2022). Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, & Stewart LA (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic reviews, 4(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AA, Blair RJ, Hettema JM, & Roberson-Nay R (2019). The genetic underpinnings of callous-unemotional traits: A systematic research review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 100, 85–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neo B, & Kimonis ER (2021). Callous–unemotional traits linked to earlier onset of self-reported and official delinquency in incarcerated boys. Law and human behavior, 45(6), 554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman KJ, & Bagner DM (2021). Treatment of Early Childhood Callous-Unemotional Traits: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go from Here. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, 60, 1348–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris LA, Rifkin LS, Olino TM, Piacentini J, Albano AM, Birmaher B, Ginsburg G, Walkup J, Compton SN, & Gosch E (2019). Multi-informant expectancies and treatment outcomes for anxiety in youth. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 50(6), 1002–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm SM, Sawrikar V, Schollar-Root O, Moss A, Hawes DJ, & Dadds MR (2019). Parents’ spontaneous attributions about their problem child: Associations with parental mental health and child conduct problems. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 47(9), 1455–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowska PJ, Tully LA, Lenroot R, Kimonis E, Hawes D, Moul C, Frick PJ, Anderson V, & Dadds MR (2017). Mothers, fathers, and parental systems: A conceptual model of parental engagement in programmes for child mental health—Connect, Attend, Participate, Enact (CAPE). Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 20(2), 146–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polaschek DL (2014). Adult criminals with psychopathy: Common beliefs about treatability and change have little empirical support. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(4), 296–301. [Google Scholar]

- Pueyo N, Navarro J-B, de la Osa N, Penelo E, & Ezpeleta L (2022). Age and sex-specific cutoff scores for the teacher-report inventory of callous-unemotional traits on children. Psychological assessment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees CA, Monuteaux MC, Herdell V, Fleegler EW, & Bourgeois FT (2021). Correlation between National Institutes of Health funding for pediatric research and pediatric disease burden in the US. JAMA pediatrics, 175(12), 1236–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyno SM, & McGrath PJ (2006). Predictors of parent training efficacy for child externalizing behavior problems–a meta‐analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(1), 99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riise EN, Wergeland GJH, Njardvik U, & Öst L-G (2021). Cognitive behavior therapy for externalizing disorders in children and adolescents in routine clinical care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review, 83, 101954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivenbark JG, Odgers CL, Caspi A, Harrington H, Hogan S, Houts RM, Poulton R, & Moffitt TE (2018). The high societal costs of childhood conduct problems: evidence from administrative records up to age 38 in a longitudinal birth cohort. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(6), 703–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salekin RT (2019). Psychopathy and therapeutic pessimism Clinical lore or clinical reality? Clinical Forensic Psychology and Law, 257–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salekin RT, Worley C, & Grimes RD (2010). Treatment of psychopathy: A review and brief introduction to the mental model mpproach for psychopathy. Behavioral sciences & the law, 28(2), 235–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MR, & Mazzucchelli TG (2022). Mechanisms of change in population-based parenting interventions for children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawrikar V, & Dadds M (2018). What role for parental attributions in parenting interventions for child conduct problems? Advances from research into practice. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 21(1), 41–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawrikar V, Hawes DJ, Moul C, & Dadds MR (2018). The role of parental attributions in predicting parenting intervention outcomes in the treatment of child conduct problems. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 111, 64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor L, & Ray DC (2021). Child-centered play therapy and social–emotional competencies of African American children: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Play Therapy, 30(2). [Google Scholar]

- Team RC (2013). R development core team. RA Lang Environ Stat Comput, 55, 275–286. [Google Scholar]

- Tennent G, Tennent D, Prins H, & Bedford A (1993). Is psychopathic disorder a treatable condition? Medicine, Science and the Law, 33(1), 63–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berk-Smeekens I, de Korte MW, van Dongen-Boomsma M, Oosterling IJ, den Boer JC, Barakova EI, Lourens T, Glennon JC, Staal WG, & Buitelaar JK (2021). Pivotal Response Treatment with and without robot-assistance for children with autism: a randomized controlled trial. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Noortgate W, & Onghena P (2003). Multilevel meta-analysis: A comparison with traditional meta-analytical procedures. Educational and psychological measurement, 63(5), 765–790. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Stouwe T, Gubbels J, Castenmiller YL, Van der Zouwen M, Asscher JJ, Hoeve M, Van Der Laan PH, & Stams GJJ (2021). The effectiveness of social skills training (SST) for juvenile delinquents: A meta-analytical review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 17(3), 369–396. [Google Scholar]

- Viding E, & McCrory E (2019). Towards understanding atypical social affiliation in psychopathy. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(5), 437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viechtbauer W (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of statistical software, 36(3), 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Gardner F, & Hyde LW (2013). What are the associations between parenting, callous–unemotional traits, and antisocial behavior in youth? A systematic review of evidence. Clinical psychology review, 33(4), 593–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, & Hyde LW (2017). Callous–unemotional behaviors in early childhood: Measurement, meaning, and the influence of parenting. Child Development Perspectives, 11(2), 120–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, & Hyde LW (2018). Callous-unemotional behaviors in early childhood: the development of empathy and prosociality gone awry. Current opinion in psychology, 20, 11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Hyde LW, Klump KL, & Burt SA (2018). Parenting is an environmental predictor of callous-unemotional traits and aggression: A monozygotic twin differences study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(12), 955–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller R, Wagner NJ, Barstead MG, Subar A, Petersen JL, Hyde JS, & Hyde LW (2020). A meta-analysis of the associations between callous-unemotional traits and empathy, prosociality, and guilt. Clinical psychology review, 75, 101809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson S, Waller R, & Viding E (2016). Practitioner review: involving young people with callous unemotional traits in treatment–does it work? A systematic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(5), 552–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.