Abstract

Uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) are highly expressed in the liver and are involved in the metabolism of many drugs. In particular, UGT1A1 has a genetic polymorphism that causes decreased activity, leading to drug-induced hepatotoxicity. Therefore, an in vitro evaluation system that accurately predicts the kinetics of drugs involving UGT1A1 is required. However, there is no such evaluation system because of the absence of the UGT1A1-selective inhibitor. Here, using human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, genome editing technology, and organoid technology, we generated UGT1A1-knockout human iPS hepatocyte-derived liver organoids (UGT1A1-KO i-HOs) as a model for UGT1A1-specific kinetics and toxicity evaluation. i-HOs showed higher gene expression of many drug-metabolizing enzymes including UGT1A1 than human iPS cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells (iPS-HLCs), suggesting that hepatic organoid technology improves liver functions. Wild-type (WT) i-HOs showed similar levels of UGT1A1 activity to primary human (cryopreserved) hepatocytes, while UGT1A1-KO i-HOs completely lost the activity. Additionally, to evaluate whether this model can be used to predict drug-induced hepatotoxicity, UGT1A1-KO i-HOs were exposed to SN-38, the active metabolite of irinotecan, an anticancer drug, and acetaminophen and confirmed that these cells could predict UGT1A1-mediated toxicity. Thus, we succeeded in generating model cells that enable evaluation of UGT1A1-specific kinetics and toxicity.

Keywords: human induced pluripotent stem cells, genome editing, hepatic organoids, drug-induced hepatotoxicity, drug metabolism, UGT1A1

Graphical abstract

Shintani and colleagues established Uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 knockout human induced pluripotent stem (UGT1A1-KO iPS) cells. They generated UGT1A1-KO iPS hepatocyte-derived liver organoids (UGT1A1-KO i-HOs) and showed that these cells can predict UGT1A1-mediated toxicity when exposed to drugs. UGT1A1-KO i-HOs could be model cells for evaluating UGT1A1-specific kinetics and toxicity.

Introduction

The liver plays an essential role in drug metabolism and detoxification. Some drugs produce highly reactive metabolites that may lead to hepatotoxicity. Drug-induced hepatotoxicity is the most frequently cited reason for abandoning compounds early in development or withdrawing them from the market after approval.1 Therefore, it is essential for pharmaceutical research to accurately evaluate the kinetic characteristics and toxicity of drugs in the liver.

Uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) are localized on the lipid bilayer of the endoplasmic reticulum, and are responsible for the metabolism of endogenous substances such as bilirubin and steroid hormones as well as various drugs.2 In recent years, because many compounds tend to be selected for their cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYPs) metabolic stability, the number of compounds metabolized by the non-CYP pathways has increased.3,4 Among non-CYP metabolizing enzymes, UGTs are involved in the metabolism of many drugs and are considered the second most important family of drug-metabolizing enzymes after CYPs. UGTs are classified into three subfamilies, UGT1A, UGT2A, and UGT2B, and 19 UGT molecular species have been identified in humans.5 UGT2B7 is the most expressed UGT isoform in human liver and is the most involved in phase II drug metabolism.6,7 Although less than UGT2B7, UGT1A1 is the fifth most expressed UGT isoform in the liver and the third most involved in drug metabolism in phase II drug metabolism.6,7 Furthermore, UGT1A1 has the following two characteristics, making it a very important enzyme among UGT molecular species. First, UGT1A1 is the only enzyme that glucuronides the endogenous substance bilirubin.8 Second, some polymorphisms of UGT1A1 enzyme have been reported to lead to their lack of activity.9,10,11,12 Crigler-Najjar syndrome is the most severe UGT1A1-related genetic disorder. These patients have a complete or near-complete lack of UGT1A1 activity, and liver transplantation is required in severe forms.13 Gilbert’s syndrome has been reported to have UGT1A1 activity reduced to about 30% of normal.14 Although milder than Crigler-Najjar syndrome, Gilbert’s syndrome is the most common UGT1A1-associated genetic disorder, affecting 3%–12% of the general population.15 Irinotecan, an anticancer drug, is known to be glucuronidated by many UGT molecular species.16,17 In particular, UGT1A1 is most involved in glucuronidation of irinotecan and has been reported to be toxic in individuals with the UGT1A1 gene polymorphism.16,17,18,19 Therefore, the development of in vitro evaluation systems that can accurately predict the pharmacokinetics of drugs involving UGT1A1 is required. However, UGTs have overlapping substrate recognition properties, many compounds are conjugated by multiple UGT isozymes, and there are no selective inhibitors for UGT1A1, making accurate prediction of UGT1A1-mediated metabolism and toxicity difficult.

Human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells (HLCs) and human iPS cell-derived hepatic organoids are expected to be used for pharmaceutical research.20,21,22,23 We have been developing a method for the differentiation of hepatocytes from human iPS cells with high efficiency.20,21,24 Previously, we have succeeded in generating CYP2C19 poor metabolizer’s model using CYP2C19-knockout (KO) human iPS cell-derived HLCs by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 system.25 We also generated CYP3A4-KO iPS cell-derived HLCs for the evaluation of CYP3A4-mediated drug-induced toxicity.26 Human iPS cell-derived hepatocyte models with knockout of pharmacokinetic-related enzymes would be a powerful tool to evaluate the contributions of specific pharmacokinetic-related enzymes.

Recently, liver organoid culture technology has been developed as a method that enables hepatocytes to maintain their functions under three-dimensional culture conditions.22,27,28,29 Organoids are more anatomically and functionally similar to living organs than conventional cultured cells and are thus expected to be applied to the study of disease pathology and pharmacokinetics. Mun et al.22 established proliferative and mature hepatic organoids from pluripotent stem cells. They found higher expression of phase I drug-metabolizing CYP enzymes and phase II detoxification enzymes and greater sensitivity to hepatotoxic drugs compared with two-dimensional (2D) hepatocytes. These characteristics indicate that hepatic organoids may be able to evaluate metabolism and drug-induced hepatotoxicity more accurately than conventional 2D hepatocytes.

In this study, we established UGT1A1-KO iPS cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. We then differentiated the UGT1A1-KO iPS cells into HLCs and established hepatic organoids from HLCs. To investigate whether these cells can predict UGT1A1-related drug metabolism and hepatotoxicity, metabolic and toxicity tests were conducted using a variety of representative drugs. To our knowledge, no prior study has reported the establishment of a UGT1A1-KO human iPS cell line. We considered that UGT1A1-KO i-HOs would be useful as a highly specific assay for the evaluation of UGT1A1-mediated kinetics and toxicity.

Results

Establishment of UGT1A1-KO human iPS cells

To establish UGT1A1-KO iPS cells, genome editing targeting exon 1 of the UGT1A1 gene was performed using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. A schematic of the genome editing experiment targeting the UGT1A1 locus is shown in Figure 1A. The donor plasmid containing the puromycin-resistance gene was linearized by CRISPR-Cas9-induced double-strand breaks, and then it was inserted into the targeted nucleotide sequence on human iPS cells by non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ). After positive selection with puromycin, we obtained 18 human iPS cell colonies. To examine whether the transgene cassette was inserted at the target locus, genotyping was performed using the primer indicated by the red arrow in Figure 1A. The primers were designed to amplify a band of 2.5 kbp for wild-type (WT) alleles and 7.0 kbp for mutant alleles. Fifteen of the 18 clones obtained (clone numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18) were monoallelically targeted at the UGT1A1 locus (Figure 1B). The WT alleles of clone numbers 2 and 12 were sequenced by the Sanger method, and a 5-base pair (bp) nucleotide deletion and a 1 bp nucleotide insertion were found near the targeted sequence (Figures S5A and 1C, respectively). To examine whether the donor plasmid was inserted for the mutant allele, the primers were designed to amplify bands of 3.1 kbp and 2.1 kbp (Figure S5B). As a result, a band was detected in UGT1A1-KO iPS cells but no band was detected in WT iPS cells. Furthermore, off-target analysis revealed no mutations at potential off-target sites of gRNA, which have 3-nt or fewer mismatches (Table S8). From these results, we succeeded in establishing UGT1A1-KO iPS cells.

Figure 1.

Establishment of UGT1A1-KO human iPS cells

(A) A schematic overview of the targeting strategy for UGT1A1 is shown. PCR primers that can distinguish the WT and mutant alleles are indicated by arrows. (B) Genotyping was performed in the UGT1A1 locus. (C) Sequencing analyses were performed to examine whether the UGT1A1-KO iPS cell clone was correctly targeted. To confirm the DNA sequence, the PCR products were purified and subjected to sequencing analyses. The indel mutations are shown in red.

Next, we examined whether UGT1A1-KO affected the pluripotent state of human iPS cells. There were no morphological differences between WT iPS cells and UGT1A1-KO iPS cells by phase-contrast images (Figure 2A). Gene expression levels of pluripotent markers (POU domain, class 5, transcription factor 1 [OCT3/4], sex-determining region Y-box 2 [SOX2], and Nanog homeobox [NANOG]) in WT iPS cells and UGT1A1-KO iPS cells were analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. The expression levels of pluripotent marker genes in UGT1A1-KO iPS cells were comparable to those in WT iPS cells, and no significant differences were observed (Figure 2B). Immunostaining analysis also showed no difference in protein expression levels of NANOG and SOX2 (Figure 2C). In addition, both WT iPS cells and UGT1A1-KO iPS cells showed normal karyotypes (Figure 2D). To evaluate the pluripotency of UGT1A1-KO iPS cells, we generated embryoid bodies (EBs) from iPS cells (Figure 2E). Real-time RT-PCR analysis showed that the gene expression levels of endoderm markers (forkhead box protein A2 [FOXA2] and sex-determining region Y-box 17 [SOX17]), mesoderm markers (kinase insert domain receptor [FLK1] and T-box transcription factor T [TBXT]) and ectoderm markers (microtubule-associated protein 2 [MAP2] and tubulin beta 3 [TUBB3]) were not changed by knockout of UGT1A1. These results suggested that knockout of UGT1A1 did not affect the pluripotent state of human iPS cells.

Figure 2.

Pluripotent capacity of UGT1A1-KO human iPS cells

(A) Phase-contrast images of WT iPS cells and UGT1A1-KO iPS cells are shown. The scale bar represents 100 μm. (B) The gene expression levels of OCT3/4, SOX2, and NANOG in WT iPS cells and UGT1A1-KO iPS cells were measured by real-time RT-PCR analysis. The gene expression levels in WT iPS cells were taken as 1.0. The data are represented as means ± SD (n = 3). (C) WT iPS cells and UGT1A1-KO iPS cells were subjected to immunostaining with anti-NANOG (red) and anti-SOX2 (green) antibodies. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). The scale bar represents 200 μm. (D) Chromosomal Q-band analyses were performed in WT iPS cells and UGT1A1-KO iPS cells. (E) The gene expression levels of endoderm markers, mesoderm markers, and ectoderm markers in WT EBs and UGT1A1-KO EBs were measured by real-time RT-PCR analysis. The gene expression levels in WT EBs were taken as 1.0. The data are represented as means ± SD (n = 3).

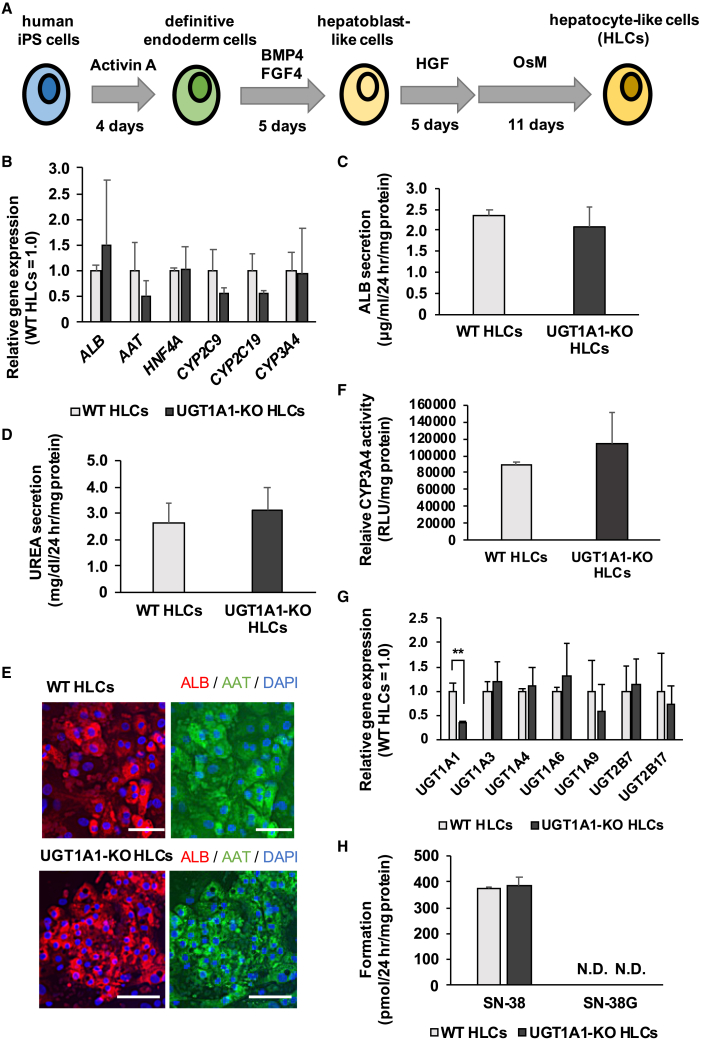

Hepatic differentiation capacity of UGT1A1-KO human iPS cells

Both WT iPS cells and UGT1A1-KO iPS cells were differentiated into HLCs as described in Figure 3A, in order to examine whether the hepatic differentiation capacity of UGT1A1-KO iPS cells was similar to that of WT iPS cells. The gene expression levels of hepatocyte markers (albumin [ALB], alpha-1 antitrypsin [AAT], hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha [HNF4A], CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4) in UGT1A1-KO iPS-HLCs were similar to those in WT iPS-HLCs (Figure 3B). There were no differences between WT iPS-HLCs and UGT1A1-KO iPS-HLCs in albumin and urea secretion capacity (Figures 3C and 3D, respectively). In addition, almost all of the HLCs were ALB- and AAT-positive (Figure 3E). The CYP3A4 activity was not significantly different between WT iPS-HLCs and UGT1A1-KO iPS-HLCs (Figure 3F). These results suggested that knockout of UGT1A1 did not affect the differentiation to hepatocytes. Furthermore, we evaluated the effect on the expression of UGT molecular species by genome editing for UGT1A1. The UGT1A1 gene expression level in UGT1A1-KO iPS-HLCs was significantly lower than that in WT iPS-HLCs, and the gene expression levels of other UGT molecular species in UGT1A1-KO iPS-HLCs were similar to those in WT iPS-HLCs (Figure 3G). However, the metabolic activity of UGT1A1 was not detected in WT iPS-HLCs (Figure 3H), suggesting that a human hepatocyte model having higher UGT1A1 activity is required.

Figure 3.

Hepatic differentiation capacity of UGT1A1-KO human iPS cells

(A) The schematic overview shows the protocol for hepatic differentiation. (B) The gene expression levels of hepatic markers (albumin [ALB], alpha-1 antitrypsin [AAT], hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha [HNF4A], CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4) were examined in WT HLCs and UGT1A1-KO HLCs by real-time RT-PCR. The gene expression levels in WT HLCs were taken as 1.0. (C) The amounts of ALB secretion in WT HLCs and UGT1A1-KO HLCs were examined by ELISA. (D) The amounts of UREA secretion were examined in WT HLCs and UGT1A1-KO HLCs. (E) WT HLCs and UGT1A1-KO HLCs were subjected to immunostaining with anti-AAT (green) and anti-ALB (red) antibodies. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars represent 100 μm. (F) The CYP3A4 activities in WT HLCs and UGT1A1-KO HLCs were examined by P450-Glo-CYP assay. The CYP3A4 activity in WT HLCs was taken as 1.0. (G) The gene expression levels of UGT markers were examined in WT HLCs and UGT1A1-KO HLCs by real-time RT-PCR. The gene expression levels in WT HLCs were taken as 1.0. (H) The UGT1A1-mediated drug-metabolizing capacities in WT HLCs and UGT1A1-KO HLCs were evaluated by quantifying SN-38 and SN-38G. The quantity of SN-38 and SN-38G was measured by UPLC-MS/MS. All data are represented as means ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance was evaluated by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (∗∗p < 0.01).

Establishment of iPS hepatocyte-derived organoids

In order to generate more matured HLCs, we then attempted to establish hepatic organoids from iPS-HLCs. Human iPS-HLCs were dissociated into single cells and embedded in Matrigel (Figure 4A). After culturing for 10 days, three-dimensional structures were formed as shown in Figure 4B. These spheroids had cell proliferative potential, indicating that we successfully established iPS-HLCs-derived hepatic organoids (i-HOs). The gene expression levels of hepatocyte markers (ALB, AAT, HNF4A, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4), UGT molecular species (UGT1A1, UGT1A3, UGT1A4, UGT1A6, UGT1A9, UGT2B7, and UGT2B17) and hepatic uptake transporters (OATP1B1, OATP1B3, and OATP2B1) in i-HOs and iPS-HLCs were analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. The gene expression levels of some markers in i-HOs were higher (HNF4A and CYP2C9, CYP2C19, OATP1B1, OATP1B3, and OATP2B1) than those in iPS-HLCs (Figures 4C and S1A). In addition, gene expression levels of UGT molecular species in i-HOs were similar (UGT1A9) or higher (UGT1A1, UGT1A3, UGT1A4, and UGT1A6) than those in iPS-HLCs. In particular, the gene expression of UGT1A1, along with the gene expression of other UGT molecular species, was increased more than about 100-fold (Figure 4D). In contrast, the expression levels of ALB, AAT, and CYP3A4 genes were decreased in i-HOs compared with those in iPS-HLCs. ALB secretion was significantly lower in WT-iHOs compared with WT HLCs, while UREA secretion was significantly higher in WT-iHOs (Figures 4E and 4F).

Figure 4.

Establishment of iPS hepatocyte-derived organoids

(A) The procedure for the establishment of i-HOs is shown. (B) The phase-contrast image by microscope of i-HOs. Scale bars represent 500 μm. (C) The gene expression levels of hepatic markers were examined in WT HLCs, WT i-Hos, and PHH (48 h) by real-time RT-PCR. The gene expression levels in WT HLCs were taken as 1.0. (D) The gene expression levels of UGTs were examined in WT HLCs, WT i-Hos, and PHH (48 h) by real-time RT-PCR. The gene expression levels in WT HLCs were taken as 1.0. (E) The amounts of ALB secretion in WT HLCs and WT i-HOs were examined by ELISA. (F) The amounts of UREA secretion were examined in WT HLCs and WT i-HOs. The drug-metabolizing capacities of CYP2C9 (G), CYP2C19 (H), and CYP3A4 (I) in WT HLCs, WT i-HOs, and PHH (48 h) were evaluated by quantifying metabolites of mephenytoin, diclofenac, and midazolam, respectively. The amounts of the metabolites (4′-hydoroxymephenytoin, 4′-hydoroxydiclofenac, and 1′-hydroxymidazolam, respectively) were measured by UPLC-MS/MS. All data are represented as means ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance between WT HLCs and WT i-HOs was evaluated by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

To examine whether culturing with liver organoid medium affects the gene expression levels of UGT1A1, we performed further experiments (Figures S3 and S4). It has been reported that forskolin increases the expression of UGT1A1.30 To investigate whether forskolin in the liver organoid medium would affect the UGT1A1 level in our model, we established i-HOs in medium with or without forskolin (Figure S3A). We found that the expression level of UGT1A1 in i-HOs was increased regardless of the presence or absence of forskolin, but the expression level increased most in the i-HOs with forskolin (Figure S3B). Additionally, when human iPS-HLCs were cultured with liver organoid medium for 7 days (Figure S4A), the gene expression level of UGT1A1 was increased (Figure S4B). Taken together, these results indicate that forskolin contributes to the increased gene expression of UGT1A1.

Next, both i-HOs and iPS-HLCs were treated with diclofenac, S-mephenytoin, and midazolam to examine the drug-metabolizing capacity of CYP2C19, CYP2C9, and CYP3A4, respectively (Figures 4G, 4H, and 4I). Metabolic activities of CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 in i-HOs were similar to those in iPS-HLCs, while that of CYP2C19 was about 13 times higher. Taken together, these results indicated that i-HOs had similar or higher drug-metabolizing enzyme activities compared with iPS-HLCs. Although the expression levels of some hepatocyte marker genes were decreased, these results suggested that improvement of liver function could be achieved by hepatic organoid technology.

In addition, we evaluated whether knockout of UGT1A1 affects the characteristics of i-HOs. The gene expression levels of hepatocyte markers (ALB, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4) in UGT1A1-KO i-HOs were similar to those in WT i-HOs (Figures S2A and S6A). There were no differences between WT i-HOs and UGT1A1-KO i-HOs in albumin and urea secretion capacity (Figures S2B and S2C, respectively). In addition, the CYP3A4 activity was not significantly different between WT i-HOs and UGT1A1-KO i-HOs (Figure S2D). These results indicated that knockout of UGT1A1 does not affect the characteristics of i-HOs.

Analysis of UGT1A1 activity in UGT1A1-KO i-HOs

Since i-HOs showed more than 100-fold higher UGT1A1 mRNA expression than iPS-HLCs (Figure 4D), we expected that i-HOs could serve as a UGT1A1-specific evaluation system. To investigate this possibility, we first analyzed the expression level of UGT1A1 in WT i-HOs and UGT1A1-KO i-HOs by real-time RT-PCR. The expression level of UGT1A1 was significantly decreased in UGT1A1-KO i-HOs (Figure 5A). In addition, protein expression of UGT1A1 was detected in WT i-HOs, but not in UGT1A1-KO i-HOs by western blotting analysis (Figure 5B). Next, to measure UGT1A1 activity, WT i-HOs and UGT1A1-KO i-HOs were treated with SN-38, one of the UGT1A1 substrates, and the amounts of SN-38 and its metabolite (SN-38G), which is produced by UGT1A1, were measured by ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS). SN-38G was not detected in UGT1A1-KO i-HOs (Figures 5C and S6B). The amount of SN-38 was greater in UGT1A1-KO i-HOs than in WT i-HOs (Figures 5D and S6C). In addition, WT i-HOs tended to produce higher amounts of metabolites than primary human hepatocytes (PHHs). These results suggested that WT i-HOs indeed had UGT1A1 activity and would be useful as an evaluation system for UGT1A1, and that UGT1A1-KO i-HOs had completely lost UGT1A1 metabolic activity.

Figure 5.

Analysis of UGT1A1 activity in UGT1A1-KO i-HOs

(A) The gene expression levels of UGT1A1 were examined in WT i-HOs and UGT1A1-KO i-HOs by real-time RT-PCR. The gene expression levels in WT i-HOs were taken as 1.0. (B) The protein expression levels of UGT1A1 and β-actin in PHH, WT i-HOs, and UGT1A1-KO i-HOs were examined by western blotting analysis. (C) The UGT1A1-mediated drug-metabolizing capacities in WT i-HOs, UGT1A1-KO i-HOs, and PHH cultured for 48 h after seeding were also evaluated by quantifying SN-38G. The amount of SN-38G was measured by UPLC-MS/MS. All data are represented as means ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance between WT i-HOs and UGT1A1-KO i-HOs was evaluated by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01).

Prediction of hepatotoxicity using UGT1A1-KO i-HOs

Finally, we evaluated whether UGT1A1-KO i-HOs could be used for predicting hepatotoxicity. For this purpose, WT i-HOs and UGT1A1-KO i-HOs were treated with two drugs that have been reported to induce liver injury, and cell viability was measured. SN-38 is the active metabolite of irinotecan, an anticancer drug, which has been reported to cause hepatotoxicity.31,32 Acetaminophen is detoxified mainly by sulfate conjugation and glucuronidation, and its glucuronidation has been reported to involve mainly in UGT1A1, UGT1A6, and UGT1A9.33,34 When these cells were treated with SN-38 and acetaminophen, the cell viability in UGT1A1-KO i-HOs was significantly lower than that in WT i-HOs (Figures 6A, 6B, and S6D). UGT1A1 is the only enzyme that can metabolize bilirubin, an endogenous substance, and the accumulation of unconjugated bilirubin causes liver injury.8,35 Therefore, we treated UGT1A1-KO i-HOs with bilirubin for 2 days and measured the cell viability. The cell viability of UGT1A1-KO i-HOs was significantly lower than that of WT i-HOs when treated with bilirubin (Figure 6C). These results suggested that UGT1A1-KO i-HOs would be useful for predicting UGT1A1-related hepatotoxicity.

Figure 6.

Prediction of hepatotoxicity using UGT1A1-KO i-HOs

WT i-HOs and UGT1A1-KO i-HOs were exposed to different concentrations of SN-38 (A), acetaminophen (B), and bilirubin (C) for 2 days. Then, the cell viability was examined by CellTiter-Glo 3D Cell Viability Assay. The cell viability was calculated as a percentage of that in cells treated with vehicle only. All data are represented as means ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance was evaluated by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01).

Discussion

In this study, we have developed a UGT1A1-specific pharmacokinetic evaluation system by application of human iPS cell culture technology, genome editing technology, and organoid culture technology. We succeeded in establishing a UGT1A1-specific KO human iPS cell-derived hepatocyte model. The UGT1A1-KO i-HOs were shown not to have UGT1A1 activity and thus to be useful for hepatotoxicity tests.

In i-HOs, the gene expression levels of CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and UGT1As were increased, while those of hepatocyte markers such as ALB and CYP3A4 were reduced (Figures 4C and 4D). Although the mechanism underlying these expression changes was not extensively investigated, we speculated that they may be attributable to the effect of certain components in the culture medium for liver organoids and the effect of the three-dimensional culture. We examined whether culture with liver organoid medium would affect the gene expression levels of UGT1As (Figures S3 and S4). When iPS-HLCs were cultured with liver organoid medium for 7 days, the gene expression levels of UGT1A1 were increased (Figures S4A and S4B), suggesting that components of the culture medium for liver organoids might affect the expression of UGT1A1. Xu et al.36 reported that when mouse-derived primary hepatocytes were treated with 8-Br-cAMP, a cAMP derivative, the gene expression levels of UGTs, including UGT1A1, were remarkably increased. Aoshima et al.30 analyzed the gene expression level of UGT1A1 in Caco-2 cells treated with several concentrations of forskolin, a cAMP signal-activator. The gene expression level of UGT1A1 increased in a forskolin concentration-dependent manner, with the 50-μM forskolin-treated group exhibiting an approximately 5-fold increase compared with the DMSO group. These studies suggested that activation of cAMP signaling induced UGT1A1 expression. Since the medium for liver organoid culture used in this study was supplemented with 10 μM forskolin, expression of UGT1As may be induced by forskolin in i-HOs. To investigate this possibility, we established i-HOs in medium with or without forskolin (Figure S3). The gene expression level of UGT1A1 was most increased in the i-HOs (forskolin+) group, but it was also significantly increased in the i-HOs (forskolin−) group, suggesting that three-dimensional culture might also be important to enhance the UGT1A1 expression. Moreover, previous studies have reported that forskolin affected the gene expression levels of hepatocyte markers in organoids. Huch et al.37 reported that the addition of forskolin to induce the proliferation of organoids decreased the gene expression levels of ALB and CYP3A4. Mun et al.22 analyzed the gene expression levels of hepatocyte markers in established 3D organoids. The expression levels of ALB and TTR were decreased compared with those in 2D mature hepatocytes, which was similar to our results (Figure 4C). In these reports, changing the medium for differentiation improved the gene expression levels of hepatocyte markers including ALB and CYP3A4 as well as the liver function. In our study, changing the medium for differentiation may also improve liver function, allowing for a more accurate assessment of hepatotoxicity and pharmacokinetics.

UGT1A1 has an important function in endogenous bilirubin detoxification. UGT1A1-KO i-HOs showed bilirubin-induced hepatotoxicity (Figure 6C). Since cell viability was not decreased in UGT1A1-KO i-HOs that were treated with low concentrations of bilirubin (<5 μM), we considered that toxicity occurs when a certain amount of unconjugated bilirubin accumulates in cells. In addition, this result showed that the UGT1A1-KO i-HOs can be successfully used to analyze bilirubin-related toxicity. Previous studies have reported that increased bilirubin concentration in the blood causes multiple organ disorders such as liver dysfunction, renal dysfunction, and neuropathy.35,38,39,40 In recent years, a microphysiological system (MPS) has attracted attention as a technology that connects multiple organ cells and reproduces an environment similar to the in vivo environment in vitro.41,42 By incorporating UGT1A1-KO i-HOs into the MPS technology, it will be possible to mimic the pharmacokinetics of bilirubin in patients with low UGT1A1 activity and systemic symptoms caused by unconjugated bilirubin.

There are many compounds that inhibit UGT1A1 activity. Among them, atazanavir is widely used as an inhibitor of UGT1A1 in Supersomes (recombinant enzymes from Corning) and microsomes.43,44,45,46,47 However, atazanavir has been reported to inhibit not only UGT1A1 but also organic anion-transporting polypeptides 1B1 (OATP1B1).48,49 In addition, it has been reported that SN-38, which we used for the prediction of hepatotoxicity, is taken up into hepatocytes by OATP1B1.50,51 Therefore, when atazanavir is used, it is difficult to accurately evaluate hepatotoxicity and pharmacokinetics in the cellular-based evaluation system due to off-target effects. UGT1A1-KO i-HOs would be an excellent evaluation system without such off-target effects.

In this study, by combining a genome editing system with human iPS cells and organoid technology, we succeeded in developing a UGT1A1-specific in vitro pharmacokinetic evaluation system. Our research will contribute to the development of highly accurate in vitro pharmacokinetic evaluation systems and the further advancement of drug discovery research.

Materials and methods

Human iPS cell culture

The human iPS cell lines, DOO-iPS cells, were generated previously.20 The cells were maintained on iMatrix-511 (Nippi, Tokyo, Japan)-coated plates with StemFit AK02N medium (Ajinomoto, Tokyo, Japan). Passaging was performed every 6 days.

Karyotyping

Karyotying of WT iPS cells and UGT1A1-KO iPS cells was carried out at the Chromosome Science Labo Inc.

Generation of EBs

Human iPS cells were dissociated into single cells with TrypLE Select Enzyme (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) and suspended in 96-well U-bottom plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 5.0 × 103 cells/well. The cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 20% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 55 μM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA), and 0.1 mM MEM-non-essential amino acids (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 7 days.

Hepatic differentiation

Human iPS cells were dissociated into single cells with TrypLE Select Enzyme and seeded on Matrigel (growth factor reduced; Corning, NY, USA)-coated plates. Differentiation of human iPS cells into hepatocytes was performed based on our previous methods with some modifications.20 Briefly, in the first step, human iPS cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) with 1x GlutaMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.5x B27 Supplement Minus Vitamin A (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 100 ng/mL Activin A (R&D Systems, MN, USA) for 4 days to induce definitive endoderm cells. In the second step, definitive endoderm cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium with 1x GlutaMAX, 0.5x B27 Supplement Minus Vitamin A, 20 ng/mL bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) 4 (R&D Systems) and 20 ng/mL fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 4 (R&D Systems) for 5 days to induce hepatoblast-like cells. In the third step, hepatoblast-like cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium with 1x GlutaMAX, 0.5x B27 Supplement Minus Vitamin A, and 20 ng/mL hepatocyte growth factor (HGF; R&D Systems) for 5 days to HLCs. In the fourth step, the cells were cultured in hepatocyte culture medium (HCM; Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) containing 20 ng/mL oncostatin M (OsM; R&D Systems) without epidermal growth factor for 11 days for maturation.

Organoid generation and culture

Human iPS-HLCs were dissociated into single cells with TrypLE Select Enzyme and passed through a strainer to remove the cell aggregates. The cells were suspended in Matrigel at 5 × 104 cells/40 μL droplet, seeded in each well of the 24-well plates, and cultured in the organoid medium containing Y-27632 (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan). The medium was replaced with the organoid medium without Y-27632 every 2 days. Table S1 shows the composition of the organoid medium, which was previously used by Huch et al.37 to generate liver organoids. The passage interval was about 8 days. The organoids were washed with cold 0.5 mM EDTA (Thermo Fisher Scientific)/PBS and treated with TrypLE Select. They were resuspended in fresh Matrigel and seeded at 40 to 60 μL each in the center of a well of a 24-well plate. The medium was replaced every 3 days.

PHH culture

Cryopreserved human hepatocytes from lot HC4-24 (XenoTech, Kansas, USA) were used. The vial of hepatocytes was rapidly thawed in a shaking water bath at 37°C; the contents of each vial were emptied into a prewarmed OptiTHAW Hepatocyte Isolation Kit (Xenotech) and the suspension was centrifuged at 900 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. The hepatocytes were seeded at 1.25 × 105 cells/cm2 in OptiPLATE Hepatocyte Plating Media (Xenotech) onto type I collagen-coated 12-well plates. The medium was replaced with HCM 6 h after seeding. The hepatocytes, which were cultured 48 h after plating the cells, were used in the experiments.

CRISPR-Cas9 plasmid

The plasmids expressing Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) and single guide RNA (sgRNA) were generated by ligating double-stranded oligonucleotides into the BbsI site of pX330 (Addgene no. 42230; http://www.addgene.org/42230/)52 and pX459 (Addgene no. 48139; https://www.addgene.org/48139/).53 The sgRNA sequences are shown in Table S2.

A universal NHEJ self-cleaving targeting plasmid was generated by conjugating the following three fragments: a universal site, an elongation factor 1α (EF1α) promoter-puromycin resistance (PuroR) gene-poly(A) signal-cassette, and linearized backbone plasmids (pENTR donor plasmids). pENTR donor plasmids were the kind gift of Dr. Akitsu Hotta (Center for iPS Cell Research and Application, Kyoto University).54 The universal site was assembled by annealing two oligonucleotides (5′-CTAGAGGGCCAGTACCCAAAAAGCGGGGGGA-3', 5′-AGCTTCCCCCCGCTTTTTGGGTACTGGCCCT-3').55

Electroporation

CRISPR-Cas9 plasmids and universal NHEJ self-cleaving targeting plasmids were used for targeting the UGT1A1 locus. Targeting was based on CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homology-independent organoid transgenesis (CRISPR-HOT) with modifications.56 First, human iPS cells were treated with 10 μM valproic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 h, dissociated with TrypLE Select Enzyme, and cells were recovered. After electroporation, the cells were seeded in AK02N medium containing 10 μM Y-27632 supplemented with iMatrix-511 at 1 μg/cm2, and then the medium was replaced with medium containing 10 μM puromycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After culturing for 2 days, the medium was switched to a normal AK02N medium. Eighteen colonies were picked up 10 days after electroporation and each colony was plated on a six-well plate coated with iMatrix-511. When each well became nearly confluent, the cellular genome was recovered and genotyping was performed by PCR.

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the cells by using ISOGENE (NIPPON GENE, Tokyo, Japan). cDNA was synthesized using 500 ng of total RNA with a Superscript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Real-time RT-PCR was performed with Fast SYBR Green master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Target mRNA expression levels were quantified relatively using the 2-ΔΔCT method. The values were normalized by those of the housekeeping gene (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)). The primer sequences used are shown in Table S3.

ALB and urea secretion

To evaluate the albumin (ALB) and urea productions in the cells, the culture supernatants, which were incubated for 24 h after the fresh medium was added, were collected. The supernatants were quantified using the Human Albumin ELISA Quantitation Set (Bethyl Laboratories, AL, USA) or the urea measurement kit (BioAssay Systems, CA, USA). The amounts of ALB and urea secretion were normalized by protein content per well, which was evaluated with a Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Immunofluorescence

To perform the immunocytochemistry, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical) for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were blocked with PBS containing 2% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 45 min, and then the cells were treated with a primary antibody and allowed to react overnight at 4°C. Cells were treated with a secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. The antibodies used are shown in Table S4.

Western blotting

The cells were homogenized with RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) after washing the cells with PBS. The samples were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatants were collected. The samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE using 10% acrylamide gel, and then transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore, MA, USA). After the reaction was blocked with 1% skim milk (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Industries) in TBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Industries) at room temperature for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (Table S5) at 4°C overnight, followed by reaction with secondary antibodies (Table S6) at room temperature for 1 h. The band was visualized by Chemi-Lumi One Super (Nakalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) and the signals were read using an LAS-4000 imaging system (FUJIFILM, Tokyo, Japan). Western blotting was performed using PHH (0 h; just after thawing) as a control.

UGT1A1 and CYPs assay

iPS-HLCs, i-Hos, and PHH were cultured with medium containing SN-38 (1 μM; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical), a UGT1A1 substrate, or cocktail-substrates for the measurements of CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4 activities (described in Table S7). After the treatment with substrates, the supernatant was collected, and then immediately mixed with acetonitrile (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical). Samples were filtrated with AcroPrep Advance 96-Well Filter Plates (Pall Corporation, NY, USA) for 5 min at 1,750 g. Then the supernatant was analyzed by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), and the concentration of each metabolite was calculated.

LC-MS/MS analysis

LC-MS/MS data were obtained by mass spectrometry (Xevo TQ-S, Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA) connected to UPLC (ACQUITY UPLC, Waters), using BEH C18 column (1.7 μm, 2.1 × 50 mm, Waters). Mobile phase A = 0.1% formic acid/water, B = 0.1% formic acid/acetonitrile, and gradient system as follows: 0 min-2% B, 1.0 min-95% B, 1.25 min-95% B, 1.26 min-2% B, and 1.75 min-2% B. The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. The limit of quantitation was 5 nM.

Assessment of drug-induced cell toxicity

The cells were treated with SN-38 (10, 50, and 100 μM), acetaminophen (5, 10, and 20 mM; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical), and bilirubin (1, 5, 10, 25, and 50 μM; Tokyo Chemical Industry, Tokyo, USA) for 2 days. The cell viability was measured using the CellTiter-Glo 3D Cell Viability Assay (Promega, WI, USA). The cell viability was calculated as a percentage of that in the cells treated with vehicle (DMSO) only.

Statistical analysis

All results are based on three biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kazuo Takayama for his excellent advice. This research was financially supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED (grant numbers 23fk0310512h0002, 23mk0101213h0003); Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research [BINDS]) from AMED (grant number JP23ama121052); the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (grant number 21K18247). Graphical abstract was created using Biorender (https://biorender.com).

Author contributions

The author’s contributions to this paper are presented below using the CRediT taxonomy.

Conceptualization: H.M.; Methodology: T.S. and J.I.; Validation: T.S. and C.I.; Formal Analysis: T.S. and C.I.; Investigation: T.S., C.I., and A.W.; Resources: H.M.; Data Curation: T.S. and C.I.; Writing – Original Draft: T.S., Y.T., and H.M.; Writing –Review & Editing: T.S., C.I., J.I., Y.T., and H.M.; Visualization: T.S. and C.I.; Supervision: H.M.; Project Administration: H.M.; Funding Acquisition: Y.T. and H.M.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtm.2023.08.003.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

Most of the data are included in the manuscript. Additional data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- 1.Watkins P.B. Drug Safety Sciences and the Bottleneck in Drug Development. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011;89:788–790. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tukey R.H., Strassburg C.P. Human UDP-Glucuronosyltransferases: Metabolism, Expression, and Disease. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2000;40:581–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cerny M.A. Prevalence of Non-Cytochrome P450-Mediated Metabolism in Food and Drug Administration-Approved Oral and Intravenous Drugs: 2006-2015. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2016;44:1246–1252. doi: 10.1124/dmd.116.070763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foti R.S., Dalvie D.K. Cytochrome P450 and Non–Cytochrome P450 Oxidative Metabolism: Contributions to the Pharmacokinetics, Safety, and Efficacy of Xenobiotics. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2016;44:1229–1245. doi: 10.1124/dmd.116.071753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackenzie P.I., Bock K.W., Burchell B., Guillemette C., Ikushiro S.i., Iyanagi T., Miners J.O., Owens I.S., Nebert D.W. Nomenclature update for the mammalian UDP glycosyltransferase (UGT) gene superfamily. Pharmacogenetics Genom. 2005;15:677–685. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000173483.13689.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams J.A., Hyland R., Jones B.C., Smith D.A., Hurst S., Goosen T.C., Peterkin V., Koup J.R., Ball S.E. Drug-drug interactions for udp-glucuronosyltransferase substrates: a pharmacokinetic explanation for typically observed low exposure (AUC I/AUC) ratios. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004;32:1201–1208. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.000794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasteel E.E.J., Darney K., Kramer N.I., Dorne J.L.C.M., Lautz L.S. Human variability in isoform-specific UDP-glucuronosyltransferases: markers of acute and chronic exposure, polymorphisms and uncertainty factors. Arch. Toxicol. 2020;94:2637–2661. doi: 10.1007/s00204-020-02765-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosma P.J., Seppen J., Goldhoorn B., Bakker C., Oude Elferink R.P., Chowdhury J.R., Chowdhury N.R., Jansen P.L. Bilirubin UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1 is the only relevant bilirubin glucuronidating isoform in man. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:17960–17964. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)32403-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosma P.J., Chowdhury J.R., Bakker C., Gantla S., de Boer A., Oostra B.A., Lindhout D., Tytgat G.N., Jansen P.L., Oude Elferink R.P., et al. The Genetic Basis of the Reduced Expression of Bilirubin UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase 1 in Gilbert’s Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:1171–1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monaghan G., Ryan M., Seddon R., Hume R., Burchell B. Genetic variation in bilirubin UDP-glucuronosyltransferase gene promoter and Gilbert’s syndrome. Lancet. 1996;347:578–581. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)91273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke D.J., Moghrabi N., Monaghan G., Cassidy A., Boxer M., Hume R., Burchell B. Genetic defects of the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase-1 (UGT1) gene that cause familial non-haemolytic unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemias. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1997;266:63–74. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(97)00167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamamoto K., Sato H., Fujiyama Y., Doida Y., Bamba T. Contribution of two missense mutations (G71R and Y486D) of the bilirubin UDP glycosyltransferase (UGT1A1) gene to phenotypes of Gilbert’s syndrome and Crigler–Najjar syndrome type II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1406:267–273. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4439(98)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jansen P.L. Diagnosis and management of Crigler-Najjar syndrome. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1999;158:S089–S94. doi: 10.1007/PL00014330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bosma P.J. Inherited disorders of bilirubin metabolism. J. Hepatol. 2003;38:107–117. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(02)00359-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilbert’s Syndrome and the Risk of Death: A Population-based Cohort Study - Horsfall. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013 doi: 10.101111/jgh.12279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanioka N., Ozawa S., Jinno H., Ando M., Saito Y., Sawada J. Human liver UDP-glucuronosyltransferase isoforms involved in the glucuronidation of 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin. Xenobiotica. 2001;31:687–699. doi: 10.1080/00498250110057341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xiao L., Zhu L., Li W., Li C., Cao Y., Ge G., Sun X. New Insights into SN-38 Glucuronidation: Evidence for the Important Role of UDP Glucuronosyltransferase 1A9. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018;122:424–428. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rouits, E., Boisdron-Celle, M., Dumont, A., Guerin, O., Morel, A., and Gamelin, E. Relevance of Different UGT1A1 Polymorphisms in Irinotecan- Induced Toxicity: A Molecular and Clinical Study of 75 Patients. Cancer Res., 10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Iyer L., King C.D., Whitington P.F., Green M.D., Roy S.K., Tephly T.R., Coffman B.L., Ratain M.J. Genetic predisposition to the metabolism of irinotecan (CPT-11). Role of uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase isoform 1A1 in the glucuronidation of its active metabolite (SN-38) in human liver microsomes. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:847–854. doi: 10.1172/JCI915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takayama K., Morisaki Y., Kuno S., Nagamoto Y., Harada K., Furukawa N., Ohtaka M., Nishimura K., Imagawa K., Sakurai F., et al. Prediction of interindividual differences in hepatic functions and drug sensitivity by using human iPS-derived hepatocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:16772–16777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413481111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takayama K., Akita N., Mimura N., Akahira R., Taniguchi Y., Ikeda M., Sakurai F., Ohara O., Morio T., Sekiguchi K., Mizuguchi H. Generation of safe and therapeutically effective human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells for regenerative medicine. Hepatol. Commun. 2017;1:1058–1069. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mun S.J., Ryu J.-S., Lee M.-O., Son Y.S., Oh S.J., Cho H.-S., Son M.-Y., Kim D.-S., Kim S.J., Yoo H.J., et al. Generation of expandable human pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like liver organoids. J. Hepatol. 2019;71:970–985. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shinozawa T., Kimura M., Cai Y., Saiki N., Yoneyama Y., Ouchi R., Koike H., Maezawa M., Zhang R.-R., Dunn A., et al. High-Fidelity Drug-Induced Liver Injury Screen Using Human Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Organoids. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:831–846.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toba Y., Kiso A., Nakamae S., Sakurai F., Takayama K., Mizuguchi H. FGF signal is not required for hepatoblast differentiation of human iPS cells. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:3713. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40305-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deguchi S., Yamashita T., Igai K., Harada K., Toba Y., Hirata K., Takayama K., Mizuguchi H. Modeling of Hepatic Drug Metabolism and Responses in CYP2C19 Poor Metabolizer Using Genetically Manipulated Human iPS cells. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2019;47:632–638. doi: 10.1124/dmd.119.086322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deguchi S., Shintani T., Harada K., Okamoto T., Takemura A., Hirata K., Ito K., Takayama K., Mizuguchi H. In Vitro Model for a Drug Assessment of Cytochrome P450 Family 3 Subfamily A Member 4 Substrates Using Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells and Genome Editing Technology. Hepatol. Commun. 2021;5:1385–1399. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang S., Wang X., Tan Z., Su Y., Liu J., Chang M., Yan F., Chen J., Chen T., Li C., et al. Human ESC-derived expandable hepatic organoids enable therapeutic liver repopulation and pathophysiological modeling of alcoholic liver injury. Cell Res. 2019;29:1009–1026. doi: 10.1038/s41422-019-0242-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akbari S., Arslan N., Senturk S., Erdal E. Next-Generation Liver Medicine Using Organoid Models. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019;7:345. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mun S.J., Lee J., Chung K.-S., Son M.-Y., Son M.J. Effect of Microbial Short-Chain Fatty Acids on CYP3A4-Mediated Metabolic Activation of Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Liver Organoids. Cells. 2021;10:126. doi: 10.3390/cells10010126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aoshima N., Fujie Y., Itoh T., Tukey R.H., Fujiwara R. Glucose induces intestinal human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A1 to prevent neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:6343. doi: 10.1038/srep06343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cai Z., Yang J., Shu X., Xiong X. Chemotherapy-associated hepatotoxicity in colorectal cancer. J. BUON. 2014;19:350–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Han J., Zhang J., Zhang C. Irinotecan-Induced Steatohepatitis: Current Insights. Front. Oncol. 2021;11:754891. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.754891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mutlib A.E., Goosen T.C., Bauman J.N., Williams J.A., Kulkarni S., Kostrubsky S. Kinetics of Acetaminophen Glucuronidation by UDP-Glucuronosyltransferases 1A1, 1A6, 1A9 and 2B15. Potential Implications in Acetaminophen−Induced Hepatotoxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2006;19:701–709. doi: 10.1021/tx050317i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Court M.H., Duan S.X., von Moltke L.L., Greenblatt D.J., Patten C.J., Miners J.O., Mackenzie P.I. Interindividual Variability in Acetaminophen Glucuronidation by Human Liver Microsomes: Identification of Relevant Acetaminophen UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase Isoforms. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut. 2001;299:998–1006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu D., Yu Q., Li Z., Zhang L., Hu M., Wang C., Liu Z. UGT1A1 dysfunction increases liver burden and aggravates hepatocyte damage caused by long-term bilirubin metabolism disorder. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021;190:114592. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu J., Kulkarni S.R., Li L., Slitt A.L. UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase Expression in Mouse Liver Is Increased in Obesity- and Fasting-Induced Steatosis. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2012;40:259–266. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.039925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huch M., Gehart H., van Boxtel R., Hamer K., Blokzijl F., Verstegen M.M.A., Ellis E., van Wenum M., Fuchs S.A., de Ligt J., et al. Long-Term Culture of Genome-Stable Bipotent Stem Cells from Adult Human Liver. Cell. 2015;160:299–312. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watchko J.F., Tiribelli C. Bilirubin-Induced Neurologic Damage — Mechanisms and Management Approaches. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:2021–2030. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1308124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Slambrouck C.M., Salem F., Meehan S.M., Chang A. Bile cast nephropathy is a common pathologic finding for kidney injury associated with severe liver dysfunction. Kidney Int. 2013;84:192–197. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Somagutta M.R., Jain M.S., Pormento M.K.L., Pendyala S.K., Bathula N.R., Jarapala N., Mahadevaiah A., Sasidharan N., Gad M.A., Mahmutaj G., Hange N. Bile Cast Nephropathy: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus. 2022;14:e23606. doi: 10.7759/cureus.23606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wikswo J.P. The relevance and potential roles of microphysiological systems in biology and medicine. Exp. Biol. Med. 2014;239:1061–1072. doi: 10.1177/1535370214542068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huh D., Hamilton G.A., Ingber D.E. From Three-Dimensional Cell Culture to Organs-on-Chips. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:745–754. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lv X., Xia Y., Finel M., Wu J., Ge G., Yang L. Recent progress and challenges in screening and characterization of UGT1A1 inhibitors. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2019;9:258–278. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang D., Chando T.J., Everett D.W., Patten C.J., Dehal S.S., Humphreys W.G. In Vitro Inhibition of Udp Glucuronosyltransferases by Atazanavir and Other Hiv Protease Inhibitors and the Relationship of This Property to in Vivo Bilirubin Glucuronidation. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2005;33:1729–1739. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.005447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Terai T., Tomiyasu R., Ota T., Ueno T., Komatsu T., Hanaoka K., Urano Y., Nagano T. TokyoGreen derivatives as specific and practical fluorescent probes for UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A1. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:3101–3103. doi: 10.1039/C3CC38810G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lapham K., Lin J., Novak J., Orozco C., Niosi M., Di L., Goosen T.C., Ryu S., Riccardi K., Eng H., et al. 6-Chloro-5-[4-(1-Hydroxycyclobutyl)Phenyl]-1H-Indole-3-Carboxylic Acid is a Highly Selective Substrate for Glucuronidation by UGT1A1, Relative to β-Estradiol. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2018;46:1836–1846. doi: 10.1124/dmd.118.083709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nardone-White D.T., Bissada J.E., Abouda A.A., Jackson K.D. Detoxication versus Bioactivation Pathways of Lapatinib In Vitro: UGT1A1 Catalyzes the Hepatic Glucuronidation of Debenzylated Lapatinib. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2021;49:233–244. doi: 10.1124/dmd.120.000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang J.H., Plise E., Cheong J., Ho Q., Lin M. Evaluating the In Vitro Inhibition of UGT1A1, OATP1B1, OATP1B3, MRP2, and BSEP in Predicting Drug-Induced Hyperbilirubinemia. Mol. Pharm. 2013;10:3067–3075. doi: 10.1021/mp4001348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karlgren M., Ahlin G., Bergström C.A.S., Svensson R., Palm J., Artursson P. In Vitro and In Silico Strategies to Identify OATP1B1 Inhibitors and Predict Clinical Drug–Drug Interactions. Pharm. Res. (N. Y.) 2012;29:411–426. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0564-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nozawa T., Minami H., Sugiura S., Tsuji A., Tamai I. Role of Organic Anion Transporter Oatp1b1 (oatp-C) in Hepatic Uptake of Irinotecan and Its Active Metabolite, 7-Ethyl-10-Hydroxycamptothecin: In Vitro Evidence and Effect of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2005;33:434–439. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.001909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fujita K.i., Sugiura T., Okumura H., Umeda S., Nakamichi N., Watanabe Y., Suzuki H., Sunakawa Y., Shimada K., Kawara K., et al. Direct Inhibition and Down-regulation by Uremic Plasma Components of Hepatic Uptake Transporter for SN-38, an Active Metabolite of Irinotecan, in Humans. Pharm. Res. (N. Y.) 2014;31:204–215. doi: 10.1007/s11095-013-1153-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cong L., Ran F.A., Cox D., Lin S., Barretto R., Habib N., Hsu P.D., Wu X., Jiang W., Marraffini L.A., Zhang F. Multiplex Genome Engineering Using CRISPR/Cas Systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ran F.A., Hsu P.D., Wright J., Agarwala V., Scott D.A., Zhang F. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:2281–2308. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li H.L., Fujimoto N., Sasakawa N., Shirai S., Ohkame T., Sakuma T., Tanaka M., Amano N., Watanabe A., Sakurai H., et al. Precise correction of the dystrophin gene in duchenne muscular dystrophy patient induced pluripotent stem cells by TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9. Stem Cell Rep. 2015;4:143–154. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schmid-Burgk J.L., Höning K., Ebert T.S., Hornung V. CRISPaint allows modular base-specific gene tagging using a ligase-4-dependent mechanism. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12338. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Artegiani B., Hendriks D., Beumer J., Kok R., Zheng X., Joore I., Chuva de Sousa Lopes S., van Zon J., Tans S., Clevers H. Fast and efficient generation of knock-in human organoids using homology-independent CRISPR–Cas9 precision genome editing. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020;22:321–331. doi: 10.1038/s41556-020-0472-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Most of the data are included in the manuscript. Additional data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.